Abstract

This study examines the direct and indirect effects of firm complexity on the accuracy of auditors’ going concern opinion (GCAO), and whether and how auditors’ work stress (AWS) can serve as a mediating variable in such a relationship. We analyzed a sample of 705 firm-year observations from 105 non-financial firms listed on the Egyptian Stock Exchange between 2017 and 2023. Binary logistic regression, OLS regression, and path analysis were employed to test the study hypotheses. The results suggested that firm complexity is negatively associated with GCAO accuracy but positively associated with AWS. Furthermore, a negative relationship was observed between AWS and GCAO accuracy. Finally, the analysis revealed that AWS mediates the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy. The findings remained robust across various sensitivity tests. Policymakers, audit firms, and investors can benefit from the findings, which emphasize the necessity of AWS mitigation techniques to improve GCAO accuracy and ultimately contribute to transparent financial reporting. This study provides unique evidence from a developing country on how firm complexity can indirectly impact the quality of auditors’ judgments.

1. Introduction

Auditors are tasked with evaluating the risks that may jeopardize a client’s continuity, determining necessary mitigation strategies, and expressing an informed opinion on its ongoing viability (Proho, 2023). However, audit clients are currently facing significant challenges, including rapid technological changes, intense competition, and shifting economic policies (Aschauer & Quick, 2024), which may threaten their continued existence. Firm complexity due to having many branches, products, or markets, and working in specialized sectors or within intricate international operations, make it difficult to track a client’s activities and operations. This, in turn, requires increased effort from the auditor. Understanding the nature of these complexities and their impact on the audit process is crucial (Mohd Sanusi et al., 2018; Tiron-Tudor & Deliu, 2022). Hence, the role of auditors in assessing the appropriateness of management’s application of the going concern assumption becomes increasingly critical.

The accuracy of the auditor’s going concern opinion (GCAO) reflects the objectivity and professionalism of their assessment of an audit client’s ability to continue operations for at least 12 months from the financial statement issuance date. It gauges the soundness of the auditor’s opinion by considering the potential for two types of errors: Type I error (Erroneous Rejection), where a modified opinion is issued on a client’s continuity despite the company’s viability for at least a fiscal year; and Type II error (Erroneous Acceptance), where an unmodified opinion is issued on a client’s continuity, but the company subsequently goes bankrupt within a fiscal year (Yang et al., 2022).

In this regard, previous studies (e.g., Bahtiar et al., 2021; Hana & Triani, 2024; Handayani et al., 2023) have shown that GCAO is influenced by the complexity of a client’s operations, where high firm complexity harms the accuracy of this opinion. This is because complex operations are often associated with significant economic, operational, and legal risks. These risks can hinder auditors’ ability to obtain sufficient evidence, accurately assess a company’s financial position, and anticipate future challenges. As firm complexity rises, so does the pressure on auditors, leading to a potential decrease in the accuracy of their work. Against the backdrop of this discussion, we are motivated to address the link between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy.

Additionally, it is widely noted that auditors today face significantly increased work stress arising from psychological pressures related to various workplace factors, including rapid economic changes, technological advancements, increased transaction volumes, pressures from clients, evolving regulations, insufficient resources, and the complexity of client operations (Afzali et al., 2024; Mannan & Darwis, 2023; Umar & Anandarajan, 2004). Numerous studies (e.g., Winoto & Harindahyani, 2021; Yan & Xie, 2016) have established a link between firm complexity and increased auditor work stress (AWS). Other studies (e.g., D. H. Pham, 2022; Suhardianto & Leung, 2020) have shown that AWS can negatively affect GCAO assessments. We extend these studies by investigating whether AWS may mediate the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy by bringing evidence from the Egyptian emerging audit market.

Our focus on the Egyptian context stems from three primary motivations. Firstly, the Egyptian market has a unique economic and regulatory landscape. Economically, Egypt has experienced rapid economic growth in recent years, coupled with periods of high inflation and currency devaluation. This dynamic economic environment creates unique challenges for businesses and auditors alike, particularly concerning going concern assessments. Furthermore, the regulatory landscape in Egypt has undergone significant changes recently, with the introduction of new accounting standards and increased emphasis on corporate governance. These regulatory developments have placed greater demands on auditors to ensure compliance and maintain audit quality (Eldyasty & Elamer, 2023). Secondly, the increasing complexity of Egyptian firms, driven by factors such as globalization and regulatory changes, requires a deeper understanding of its influence on AWS and GCAO accuracy. Lastly, the potential for AWS to mediate this relationship is particularly relevant in the Egyptian context as an emerging audit market with a lack of enforcement of and compliance with regulations (Amara et al., 2023; Gontara et al., 2023; Kamal Hassan, 2008; Khelil et al., 2023), where auditors may face significant pressures and challenges in fulfilling their duties.

This study addresses the research gap in understanding the indirect effects of firm complexity on the GCAO. While previous research has examined the direct relationship between these two variables, this study delves deeper by exploring the mediating role of AWS. Specifically, our study aims to answer the following research questions: (1) Is there a direct relationship between firm complexity and the GCAO? (2) Is there a direct relationship between firm complexity and AWS? (3) Is there a direct relationship between AWS and the GCAO? (4) Does AWS mediate the relationship between firm complexity and the GCAO? Accordingly, the primary objective of this study is to investigate the impact of firm complexity on both GCAO and AWS. Additionally, the study aims to examine the effect of AWS on the GCAO. Furthermore, the research will explore the direct and indirect effects of firm complexity on the GCAO, with AWS serving as a mediating variable in this relationship.

By using binary logistic regression, OLS regression, and path analysis for a sample of non-financial companies listed on the Egyptian Stock Exchange, the results of our study suggest that firm complexity negatively affects GCAO accuracy. Furthermore, firm complexity is found to positively affect AWS. Moreover, AWS negatively influences GCAO accuracy. Finally, our findings revealed that AWS mediates the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy. Sensitivity analysis largely supported these findings.

This study contributes to the existing body of knowledge on the factors influencing GCAO (Yang et al., 2022). While previous research referred to the direct relationship between firm complexity and audit opinion accuracy (Khan et al., 2023), this study delves deeper into exploring the mediating role of AWS. Thus, this study extends our understanding of the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy by introducing AWS as a mediating factor. Also, by focusing on the Egyptian market, the study provides valuable empirical evidence from a unique economic and regulatory context. By doing so, this study clarifies the direct and indirect effects of firm complexity on GCAO accuracy.

In addition, given the importance of accurate going concern audit opinions in building stakeholders’ confidence in the auditing profession, which is especially needed in emerging markets, this research provides valuable insights into the audit field. In particular, by identifying factors that influence GCAO accuracy, Egyptian regulatory bodies can develop regulations that promote higher accuracy, ultimately enhancing the reliability of financial reports and protecting investors’ interests. Accurate going concern opinions serve as independent assessments of a company’s short-term viability, making them crucial for informed decision-making by investors and the economy as a whole. Finally, the current findings emphasize to auditors and audit clients the importance of managing AWS to improve the quality of audit judgments and enhance the reliability of financial reporting.

2. Egyptian Context

The Egyptian Auditing Standard (EAS) No. 570, which corresponds to ISA 570, outlines auditors’ responsibilities regarding the going concern assumption. According to this standard, the auditor must assess the appropriateness of management’s application of this assumption and the adequacy of their disclosures in the financial statements. This responsibility includes subsequent events that may cast doubt on the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. Egyptian Auditing Standard (EAS) No. 570 is based on the internationally recognized ISA 570, which has been in place for approximately 10 years; its implementation in Egypt occurred more recently. The last update to ISA 570 (Going Concern) was in 2020. The standard has been amended to reflect changes in the business environment, particularly in light of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on entities’ ability to continue as a going concern.

Based on the assessment of management’s application of the going concern assumption and the adequacy of their disclosures, the auditor should issue an unmodified opinion if management’s application is appropriate and disclosures are adequate following ISA 700. He should include a separate paragraph on material uncertainty regarding going concern following the basis for the opinion paragraph. However, a modified opinion should be issued if management’s application is inappropriate, or disclosures are insufficient or absent. Then, auditors must modify their opinion (qualified or adverse) following ISA 705. They should explain the reasons for the modification as the basis of the opinion.

Regarding the issue of firm complexity, Egyptian auditing standards do not explicitly address it in detail. However, some standards, such as Egyptian Auditing Standard No. 315, require auditors to assess inherent risks in financial statements, including those associated with operational and system complexity. Furthermore, Egyptian Auditing Standard No. 330 emphasizes that audit procedures should be tailored to address identified risks, including those arising from operational complexity.

It is important to note that Egyptian auditing standards do not explicitly address auditor stress (AWS). However, certain standards, such as Egyptian Auditing Standards No. 300 and 315, may implicitly contribute to it. These standards emphasize the importance of thorough audit coverage and comprehensive risk assessments, which can increase workload and time pressure, potentially contributing to increased stress levels among auditors.

Beyond the specific requirements outlined in Egyptian auditing standards, the Egyptian economic and regulatory landscape presents a unique and complex environment for audit practitioners. The Egyptian economy has exhibited periods of rapid growth interspersed with episodes of economic shock, including currency fluctuations and inflationary pressures. This inherent volatility within the economic environment can significantly increase the complexity of assessing a company’s going concern status, as businesses may be exposed to sudden and unforeseen disruptions to their operating environment. Furthermore, the regulatory landscape in Egypt is characterized by ongoing reform initiatives aimed at strengthening corporate governance and enhancing the quality of financial reporting. These ongoing regulatory changes present auditors with additional complexities as they strive to navigate the evolving regulatory framework and ensure compliance with the latest requirements (Ghattas et al., 2021).

The Egyptian audit market itself is characterized by a mix of large international firms and smaller local practices. This diversity can lead to variations in audit quality and resources, potentially influencing how auditors approach going concern assessments. Furthermore, the level of enforcement of auditing standards and regulations in Egypt is an important contextual factor. While efforts have been made to strengthen enforcement, challenges remain, which may impact auditor behavior and the perceived consequences of inaccurate going concern opinions. The interplay of these economic, regulatory, and market-specific factors creates a unique context for examining the relationship between firm complexity, auditor work stress, and the accuracy of going concern opinions in Egypt. Our study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of these dynamics within this important emerging market (Ghattas et al., 2021).

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Firm complexity refers to the intricate nature of an audit client’s operations and activities, which significantly affects the auditor’s workload. This issue can be assessed by some factors, including the size of the entity, the technology used, the regulatory environment, and the structure of the entity (Khan et al., 2023; Tiron-Tudor & Deliu, 2022). The complexity of the audit client’s operations can have serious implications for the audit process concerning the time required to conduct the audit process, the difficulty of obtaining sufficient evidence to support auditor opinion, and the risk of not discovering errors or fraud (Chen et al., 2024). These issues can reduce the quality of the audit report, which, in turn, reduces its usefulness to users. Hence, the existence of firm complexity raises doubts about the accuracy of GCAO.

GCAO is an independent professional assessment provided by auditors on the ability of the audit client to normally continue its operations in the future, i.e., within a period of at least one year from the financial statements’ issuance date, without the need for liquidation or a significant reduction in its activity (Hutagalung et al., 2024; Polo et al., 2023). Such an assessment is subject to two types of error, where Type I error occurs when a modified opinion is issued for an entity that continues, and a Type II error occurs when an unmodified opinion is issued for an entity that subsequently fails. Firms, external stakeholders, and the whole economy are significantly affected by the accuracy of auditors’ opinions by helping them better assess the existing risks. Accurate auditor opinion can also improve financial market efficiency and reduce the chance of business failure (Chu et al., 2024; Geiger et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024).

To overcome such complexity and its anticipated effects on the accuracy of auditor opinion, the auditor should develop a detailed audit plan that takes into account the level of complexity, allocate the necessary human and financial resources to complete the audit process, and utilize recent information technology tools such as artificial intelligence to facilitate the audit process and maintain continuous communication with the firm’s management to clarify any unclear issues. While developing a detailed plan, allocating resources, and maintaining communication can contribute to auditor workload, the effective use of AI and other technologies is expected to reduce work stress by automating routine tasks, improving efficiency, and enhancing audit quality (Fedyk et al., 2022).

AWS can be defined as a psychological and physical strain caused by work environment factors and task demands, which can negatively influence performance and overall well-being (Mannan & Darwis, 2023; Nelson & Smith, 2023). AWS can have some dimensions, such as workload pressure, task complexity, uncertainty, responsibility for accurate financial reporting and maintaining impartiality and ethical standards, the anxiety of making mistakes and potential legal repercussions, and, finally, the need to cope with the latest technological advances in the accounting and audit environments. Hence, it is crucial to address the influences of AWS because it might have several detrimental consequences on the quality of the audit process, representing increased errors, decreased productivity, increased tension, reduced teamwork, higher litigation risk, and compromised professional independence (Kesimli et al., 2018; Umar & Anandarajan, 2004; Van Hau et al., 2023).

3.1. Firm Complexity and GCAO Accuracy

According to the risk theory, it is based on the idea of understanding and evaluating uncertain events that may affect the targeted results of the audit client’s entity. It expresses the possibility of a negative or undesirable event occurring, which may lead to financial, material, or moral losses for the audit client’s entity (Ombati & Karuti, 2024). The risk theory is one of the foundations that auditors rely on to assess the continuity of the audit client’s entity, as this theory includes analyzing the risks associated with the operations of the audit client’s entity, which increase as the complexity of these operations increases. This theory assumes that the simpler the operations of the audit client’s entity, the lower the risks, which makes it easier for auditors to accurately assess the continuity of the audit client’s entity. Meanwhile, the increased complexity of these operations leads to increased risks, which requires auditors to conduct more in-depth assessments, which may affect the accuracy of their opinion regarding the continuity of the audit client’s entity (Ombati & Karuti, 2024).

Additionally, from the information theory perspective, the accuracy of auditors’ opinions hinges on the quantity and quality of information accessible to them about the audit client’s firm. This becomes a crucial issue when dealing with complex operations. Such complexity can lead to challenges in data collection from multiple sources, and the information derived may be inaccurate or unreliable, potentially negatively impacting auditors’ opinions on the client firm’s continuity (X. Li & Sun, 2024).

Thus, recent studies (e.g., Bahtiar et al., 2021; Hana & Triani, 2024; Handayani et al., 2023) have demonstrated that GCAO could be influenced by the complexity of a firm’s operations. This is based on the view that complex operations often expose firms to heightened economic, operational, and legal risks, making it challenging for auditors to accurately assess the firm’s financial health and anticipate future challenges. Moreover, complexity can hinder auditors’ ability to obtain sufficient evidence to verify the accuracy of the financial information provided by the firm, increasing the likelihood of assessment errors. As firm complexity escalates, so does the pressure on auditors, potentially compromising the accuracy of their work.

Within the Egyptian professional business environment, the relationship between firm complexity and the accuracy of auditors’ opinions on firm continuity is exacerbated by various factors. In particular, the existing heightened economic fluctuations, including inflation and currency instability, hinder accurate financial forecasting. Egypt has experienced consistently high inflation rates, averaging 12.1% over the past ten years (World Bank, 2023), and significant currency volatility, with the Egyptian pound experiencing over 50% devaluation against the US dollar in the past few years. Furthermore, the prevalent corruption and favoritism can distort financial information, obstructing auditors’ ability to assess the firm’s financial health. Reports from Transparency International (the 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index ranked Egypt 126th out of 180 countries) indicate that corruption in Egypt manifests in various forms, including bribery, nepotism, and cronyism. These practices can lead to the manipulation of financial records, the misrepresentation of assets and liabilities, and the concealment of related party transactions, making it difficult for auditors to obtain a true and fair view of a company’s financial position. The prevalence of corruption and favoritism has several negative consequences for the Egyptian economy, including reduced foreign direct investment due to increased perceived risk, decreased investor confidence, and a weakening of the overall business environment. It also undermines fair competition and resource allocation, hindering economic growth. While weak oversight over auditing practices, as discussed by Awadallah and Elsaid (2020) and Saleh (2023), presents a challenge to data reliability, we have taken several steps to mitigate its potential impact on our study. First, we focused on objective financial data reported by the firms themselves (e.g., financial ratios, going concern opinions issued), rather than relying solely on subjective auditor assessments. Second, we used data from multiple years (2017–2023) to identify trends and patterns in the data, which can help to reduce the influence of any single year’s reporting irregularities.

Considering the above discussion and as informed by the risk theory, the information theory, and the specificity of the Egyptian context, the first hypothesis of this study can be derived as follows:

H1.

Firm complexity significantly affects GCAO accuracy.

3.2. Firm Complexity and AWS

The expected association between firm complexity and AWS is based on several theories, perhaps the most important of which are the theory of tasks and the theory of uncertainty (e.g., De Brabander & Martens, 2014; Lim & Mali, 2024). The theory of tasks posits a direct correlation between the intricacy of an audit client’s tasks and processes and the corresponding effort and time auditors must spend. In essence, more complex operations demand greater scrutiny and, consequently, more extensive audit work. This increased complexity can lead to a heavier workload and heightened pressure on auditors, as they are required to undertake a larger number of tasks (De Brabander & Martens, 2014).

The theory of uncertainty emphasizes the inherent unpredictability of future events. This theory suggests that as the complexity of an audit client’s operations grows, so does the uncertainty on the accuracy of their financial information. To mitigate this risk, auditors must invest additional effort in verifying the accuracy of the data, leading to increased workload and pressure (Lim & Mali, 2024). In this regard, Yan and Xie (2016) noted that auditor workload exerts a more significant influence on audit quality in the context of new client audits. Furthermore, Winoto and Harindahyani (2021) highlighted the cognitive burden imposed on auditors due to reviewing complex operations. This is because complex processes necessitate a greater expenditure of cognitive resources on the part of auditors to fully understand and evaluate these processes, thereby directly increasing their workload.

In the Egyptian context, the relationship between firm complexity and AWS is influenced by several factors, as follows. The prevalence of large family businesses with less formal organizational structures and flexible operations can lead to less organized financial statements and increased error potential. The volatile Egyptian economic environment introduces uncertainty and requires auditors to exert more effort in assessing risks and applying appropriate audit procedures. Furthermore, the significant informal economy component poses challenges in obtaining accurate and reliable financial information. Additionally, the prevalence of foreign currency transactions in Egyptian firms adds complexity to auditing processes and necessitates knowledge of exchange rates and relevant accounting rules. Finally, the reliance of many Egyptian firms on outdated information systems can hinder data collection and analysis, further contributing to auditor stress (Farghaly et al., 2024). Based on the above discussion, the second hypothesis of this study can be set as follows:

H2.

Firm complexity significantly affects AWS.

3.3. AWS and GCAO Accuracy

The expected association between AWS and GCAO accuracy can be notably explained through cognitive evaluation, burnout, and goal theories (Peytcheva, 2014; Q. T. Pham et al., 2022; Salehi et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2017). The cognitive evaluation theory posits that elevated stress levels can impair human cognitive function. This diminished cognitive capacity can hinder individuals’ (including auditors) ability to make sound judgments, potentially leading to errors in assessing an entity’s financial health. When auditors are subjected to significant work pressure, they may struggle to accurately assess the risks associated with an audit client’s continuance. This heightened pressure can result in auditors’ ignorance of critical indicators of financial distress, ultimately compromising the accuracy of their opinion on the firm’s going concern status (Peytcheva, 2014; Shi et al., 2017).

The theory of burnout posits that prolonged exposure to stress can lead to emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion. This state of burnout can impair auditors’ focus and analytical abilities, increasing the risk of errors in assessing an audit client’s financial health. Consequently, the accuracy of their opinion on the firm’s going concern status may be compromised (Salehi et al., 2020).

The goal theory suggests that clear, realistic, and attainable goals can motivate individuals to work harder. Conversely, unrealistic or unachievable goals can lead to frustration and stress. In the context of auditing, if auditors are assigned unrealistic deadlines, they may experience significant work stress. This increased pressure can induce them to rush their work and neglect necessary analyses, ultimately compromising the accuracy of their opinion on client firms’ going concern (Q. T. Pham et al., 2022). Under pressure, auditors may focus on specific aspects of the audit, neglecting other potentially more critical areas relevant to the continuity assessment (Q. T. Pham et al., 2022). In this regard, Suhardianto and Leung (2020) emphasized the negative relationship between AWS and GCAO.

Several factors might contribute to the relationship between auditor stress (AWS) and audit opinion accuracy in Egypt. These include heavy workloads, which can reduce the time available for in-depth audits and analysis, and resource constraints, such as financial and human resource shortages. Furthermore, the challenging economic environment, characterized by volatility, including currency fluctuations and inflationary pressures, complicates the audit process. This economic instability can make financial forecasting unreliable and increase the difficulty of assessing firm continuity, potentially affecting audit opinion accuracy. Finally, the political and economic instability at the country level can further complicate the audit process and make it challenging to evaluate firm continuity (Farghaly et al., 2024; Saleh, 2023). Considering the above, we formulate the third hypothesis as follows:

H3.

AWS significantly affects the accuracy of GCAO.

3.4. The Mediating Role of AWS

The relationship between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy is not likely to be entirely direct. We argue that AWS plays a crucial mediating role in this relationship. This mediation suggests that the impact of firm complexity on GCAO accuracy is channeled, at least in part, through the level of stress experienced by the auditor. This aligns with and expands upon the cognitive evaluation theory, the job demands–resources (JD-R) model, and builds upon the established links between firm complexity, AWS, and GCAO accuracy (Jefferson et al., 2024).

Firm complexity, as discussed earlier, increases the demands placed on auditors. Complex operations require more extensive audit procedures, greater professional skepticism, and a deeper understanding of the client’s business. This heightened demand translates into increased auditor workload, longer hours, and more intense scrutiny of financial information. This directly connects to the demands component of the JD-R model (Jefferson et al., 2024). The JD-R model suggests that job demands, when excessive, can lead to strain, including work stress. Therefore, increased firm complexity, by increasing audit demands, contributes to higher AWS.

Furthermore, the cognitive evaluation theory suggests that stress can impair cognitive functions. When auditors experience high levels of work stress due to the demands of auditing complex firms, their ability to process information, make sound judgments, and accurately assess going concern issues can be negatively affected (Peytcheva, 2014; Shi et al., 2017). This impaired cognitive function, resulting from stress induced by firm complexity, can lead to errors in judgment and a reduction in the accuracy of the GCAO. Auditors under stress may be more likely to overlook subtle but important indicators of financial distress, or they may make less effective use of available audit evidence. This diminished cognitive capacity is a direct pathway through which AWS mediates the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy.

In addition to the JD-R model and cognitive evaluation theory, the concept of resource scarcity can further explain the mediating role of AWS. As firm complexity increases, the resources available to auditors (time, personnel, expertise) may become strained. The increased workload associated with complex audits can lead to time pressure, potentially forcing auditors to cut corners or make quick decisions without sufficient analysis. This resource scarcity, exacerbated by firm complexity, contributes to AWS. The resulting stress further reduces the likelihood of thorough and accurate going concern assessments.

Therefore, the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy is not simply a direct one. Firm complexity increases the demands placed on auditors, leading to increased AWS. This stress, in turn, impairs cognitive function, reduces available resources, and ultimately negatively impacts the accuracy of the auditor’s going concern opinion. This chain of events highlights the critical mediating role of AWS. Hence, the fourth hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H4.

AWS mediates the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy.

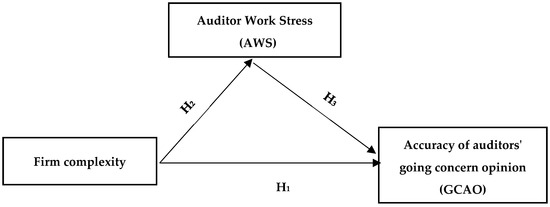

Figure 1 illustrates the research model that depicts the mediating role of AWS in the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO.

Figure 1.

The research model. Source: created by the authors.

4. Research Design

4.1. Sample Selection

This study analyses publicly traded firms listed on the Egyptian Stock Exchange from 2017 to 2023. The focus on listed companies is justified for several reasons. First, listed firms are subject to more stringent regulatory requirements and disclosure obligations than unlisted firms, including mandatory annual audits conducted in accordance with recognized accounting standards. This makes their financial data more readily available and reliable for research purposes (Alsheikh & Alsheikh, 2023; Moez, 2024). Second, listed companies typically have more complex and larger scale operations than unlisted firms, making them particularly relevant for investigating the relationship between firm complexity, auditor work stress, and the accuracy of going concern opinions. Third, the auditing processes of listed companies are often more rigorous due to increased scrutiny from investors, regulators, and the public. This heightened scrutiny can influence auditor behavior and potentially impact the quality of audit opinions. Finally, the study period commences in 2017, coinciding with the widespread adoption of corporate governance reporting practices by Egyptian firms, which enhances the availability and comparability of relevant data. Financial institutions, such as banks and insurance companies, were excluded from the study due to their distinct regulatory frameworks and operational nature, which differ significantly from non-financial firms. A final sample of 105 firms was selected after applying the following criteria: being listed on the stock exchange, publication of annual reports throughout the study period, and the availability of financial statements in Egyptian pounds. Firms lacking accessible financial statements were excluded, resulting in a total of 705 firm-year observations. Table 1 presents the distribution of the sample firms across various industry sectors, outlining the number and percentage of firms in each sector relative to the total sample size.

Table 1.

Sample selection.

4.2. Variables’ Measurement

4.2.1. Dependent Variable

GCAO, the study’s dependent variable, is assessed by comparing auditors’ judgments to the predictions of the Altman model. The Altman Z-Score model, used to assess the financial health and predict the likelihood of bankruptcy for firms, is calculated as follows (Nworie & Obi, 2024):

where

Z = 1.2X1 + 1.4X2 + 3.3X3 + 0.6X4 + 1X5

X1 = working capital to total assets ratio

X2 = retained earnings to total assets ratio

X3 = profit before interest and tax to total assets

X4 = market value of equity to book value of total liabilities

X5 = revenue to total assets

An accurate opinion is indicated when an auditor correctly identifies a firm as financially distressed (by issuing a modified opinion) or financially stable (by issuing an unmodified opinion). The Altman model, a reliable predictor of financial distress, serves as a benchmark. The dependent variable is a binary one, taking a value of “1” if the auditor’s opinion aligns with the Altman model, and 0 otherwise (Wang et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2022).

4.2.2. Independent Variable

Firm complexity, the study’s independent variable, refers to the difficulty of monitoring a client’s multifaceted operations due to having, for instance, numerous branches, diverse product offerings, and extensive markets (Chen et al., 2024). Previous research (Barinov et al., 2024; Khan et al., 2023; Loughran & McDonald, 2023) has identified eight measures of firm complexity: the logarithm of total assets, inventory turnover rate, AR turnover rate, industry dummy (for complex sectors like banks, technology, finance, communications, petroleum, and insurance), number of branches, number of operations or products, using complex accounting estimates, and financial performance indicators (return on assets and return on equity). In our main analysis, we measured firm complexity using the inventory turnover rate calculated by dividing the cost of goods sold by average inventory. However, for sensitivity analysis, we employed financial performance indicators, such as return on equity (ROE).

4.2.3. Mediating Variable

We use AWS as a mediating variable, as this variable refers to auditor stress stemming from workplace factors like client pressures, regulatory changes, resource constraints, and complex client operations (Mannan & Darwis, 2023). For the main analysis, this variable was measured as the natural logarithm of the audit client’s total assets. In joint audits, the value is halved for each auditor, and in three-auditor engagements, it is divided by three, as shown in the following equation (Talebkhah, 2020):

where TAij is the natural logarithm of the total assets of (j) firms that the auditor (i) audited in the fiscal year, n is the total number of listed firms that the auditor audited, and m is the number of a certain j firm’s official auditors.

For the sensitivity analysis, AWS was measured as the natural logarithm of the total assets of all clients for each year regardless of the number of auditors, as proposed by Winoto and Harindahyani (2021). The following equation is used to determine AWS:

4.2.4. Control Variables

This study incorporated several control variables to account for potential factors influencing GCAO accuracy and auditors’ work stress levels (Hutagalung et al., 2024; Uthman et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024), as follows.

Growth rate = (Current year revenue − Previous year revenue)/Previous year revenue.

Current ratio = Current assets/Current liabilities.

Cash flows from operating activities ratio = Cash flows from operating activities/Total assets.

Debt ratio = Total liabilities/Total assets.

Return on assets = Net profit after interest and taxes/Total assets.

Loss = 1 if net profit before exceptional items is negative, 0 otherwise.

Audit firm reputation = Total assets of the auditor’s clients in a specific industry/Total assets of the clients of the industrial sector in the study sample.

4.3. Model Specification

To formally test the mediating role of AWS in the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy (H4), we will employ the approach recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986) and further developed by subsequent researchers. This approach involves examining the significance of the indirect effect of firm complexity on GCAO accuracy through AWS. We will estimate the following three regression models.

4.3.1. Firm Complexity and the GCAO Accuracy Model

The impact of firm complexity on GCAO accuracy (H1) is estimated using the following model:

where GCAO is the accuracy of the auditor’s going concern opinion, Complex.Oper. is firm complexity, GROWTH is growth rate, CURR is current ratio, CFO is cash flows from operating activities ratio, DEBT is debt ratio, ROA is the return on assets, and LOSS is a dummy variable for a negative return on assets. This model estimates the total effect of firm complexity on GCAO accuracy, without considering the mediating variable. β1 in this model represents the total effect.

GCAO (it) = β0 + β1 Complex.Oper.(it) + β2 GROWTH(it) + β3 CURR.(it) + β4 CFO.(it) + β5 DEBT(it) + β6 ROA(it) + β7 LOSS(it) + ε(it)

4.3.2. Firm Complexity and the AWS Model

The impact of firm complexity on the auditor’s work stress (H2) is estimated using the following model:

where AWS represents the auditor’s work stress and AFR represents the audit firm’s reputation. Other variables are defined in Model 1. This model estimates the effect of firm complexity on the mediator, AWS. β1 in this model represents the effect of the independent variable on the mediator.

AWS(it) = β0 + β1 Complex.Oper.(it) + β2 GROWTH(it) + β3 CFO.(it) + β4 DEBT(it) + β5 LOSS(it) + β6 AFR(it) + ε(it)

4.3.3. AWS and GCAO Accuracy Model

The impact of AWS and firm complexity on GCAO (H3) is estimated using the following model:

GCAO (it) = β0 + β1 AWS (it) + β2 Complex.Oper.(it) + β3 GROWTH(it) + β4 CURR.(it) + β5 CFO.(it) + β6 DEBT(it) + β7 ROA(it) + β8 LOSS(it) + ε(it)

All variables are as defined in Models 1 and 2. This model estimates the effect of both firm complexity and the mediator (AWS) on GCAO accuracy. β1 in this model represents the effect of the mediator on the dependent variable, and β2 represents the direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, controlling for the mediator.

4.3.4. The Mediating Role of AWS (Model 4—Indirect Effect)

While not a separate regression, the crucial step in testing mediation is assessing the indirect effect, which is the product of the β1 from Model 2 and β1 from Model 3. We will use bootstrapping to determine the statistical significance of this indirect effect.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents a statistical summary of the study variables. The table includes measures of central tendency (mean) and dispersion (standard deviation, maximum, and minimum) for each variable. The data appears relatively stable, with the means falling within the range of observed values and low standard deviations. However, the growth rate variable exhibits greater variability, which is likely attributable to the diverse sample of 105 firms (705 observations) spanning various sectors and economic conditions.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

5.2. Multicollinearity Diagnostics Test

To evaluate the presence of multicollinearity among independent variables, this study employed the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). A VIF value exceeding 10 typically signals potential multicollinearity issues (Abouelela et al., 2025). As indicated in Table 3, all VIF values were below this threshold, confirming the absence of multicollinearity problems.

Table 3.

Multicollinearity test.

5.3. Correlation

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the strength of the relationships between the independent and control variables. To assess the distribution of our data, we conducted the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality. The results of this test indicated that the data followed a normal distribution. Given the results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, we proceeded with Pearson’s correlation analysis. A threshold of 0.7 was employed, with values below this limit indicating a weak association and mitigating concerns about multicollinearity (Abouelela et al., 2025). Table 4 presents the correlation matrix, with all coefficients below 0.7, confirming the absence of multicollinearity and supporting the use of multiple regression analysis (binary logistic regression, OLS regression, and path analysis).

Table 4.

Pearson correlation coefficients.

5.4. Main Findings

Table 5 presents the main results of the analysis. Results of testing H1 (i.e., whether firm complexity significantly affects GCAO) (model 1) are presented in panel A. A Cox and Snell R Square of 0.287 indicates that 28.7% of the variation in GCAO can be explained by changes in the independent variable (firm complexity). The model’s overall significance is supported by a highly significant p-value (0.000), which is below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.05. This confirms the model’s validity in examining the hypothesized relationship. Furthermore, the coefficient of firm complexity is negative and statistically significant (−0.315, p-value = 0.000), indicating a significant and negative influence on GCAO. Thus, H1 is accepted.

Table 5.

Statistical results of basic analysis.

This finding is consistent with the principles of the risk theory, and the information theory, ensuring that firm complexity can negatively influence auditors’ assessments of a firm’s continuity. Furthermore, the current finding aligns with some previous studies (e.g., Bahtiar et al., 2021; Hana & Triani, 2024; Handayani et al., 2023). In other words, obtaining sufficient evidence to corroborate the accuracy of financial information becomes more difficult in complex environments, increasing the likelihood of errors in auditors’ assessments. Concerning the influence of control variables, Table 5, Panel A, further reveals a significant and positive association between the current ratio, return on assets, and GCAO. These results are consistent with Siahaan et al. (2024).

Moreover, the current finding aligns with the Egyptian context, with higher levels of firm complexity that are often linked to challenges in financial transparency and regulatory compliance. In Egypt, the potential for opaque operating environments exists, which can pose challenges for auditors in ensuring complete alignment between operational details and financial realities (Kamal Hassan, 2008). However, the financial data used in this study is still subject to regulatory requirements and auditing standards, providing a foundation for examining the relative accuracy of going concern opinions.

Panel B of Table 5 presents the results of testing H2 (the impact of firm complexity on AWS) (Model 2). The Adjusted R2 of 0.435 indicates that 43.5% of the variation in AWS can be explained by changes in the independent variable (firm complexity). The model’s overall significance is supported by a highly significant p-value (0.000). This finding confirms the model’s validity in examining the hypothesized relationship. Furthermore, the coefficient of firm complexity is positive and statistically significant (1.207, p-value = 0.003), indicating a significant and positive influence on AWS, supporting the acceptance of H2. Concerning the influence of control variables, Panel B further reveals a significant and positive association between debt ratio and AWS, which is consistent with Amiruddin (2019). The results also indicate a significant negative correlation between growth rate, cash flows from operating, audit firm reputation, and AWS, which is consistent with Blum et al. (2022).

This result aligns with both the theory of tasks and the theory of uncertainty. Furthermore, the current finding aligns with some previous studies (e.g., Winoto & Harindahyani, 2021; Yan & Xie, 2016). It confirms that firm complexity increases audit work difficulty by requiring significant time and effort to comprehend the nature of audit processes. It also indicates that complex firms are more susceptible to errors and fraud, prompting auditors to exert greater effort in identifying and evaluating these risks, thereby exacerbating their work pressure.

Moreover, our finding aligns with the Egyptian context, where many firms face significant operational complexities due to factors such as diverse business activities, regulatory challenges, and economic fluctuations. Egyptian auditors often encounter intricate financial structures and varied reporting requirements, which can increase their workload and contribute to elevated stress levels. This context underscores the importance of recognizing and addressing work stress in the Egyptian auditing profession. It also highlights the need for strategies to support auditors in navigating complex environments, ultimately enhancing their performance and well-being in the face of increasing demands.

Panel A of Table 5 presents the results of testing Model 3, which examines the impact of AWS on GCAO (H3). A Cox and Snell R Square of 0.324 indicates that 32.4% of the variation in GCAO can be explained by changes in the independent variable (AWS). The model’s overall significance is supported by a highly significant p-value (0.000). This confirms the model’s validity in examining the hypothesized relationship. Furthermore, the coefficient of AWS is negative and statistically significant (−0.044, p-value = 0.000), indicating a significant and negative influence on the GCAO, supporting the acceptance of H3.

This finding is consistent with the principles of cognitive evaluation, burnout, and goal theories. Furthermore, the current finding aligns with some previous studies (e.g., D. H. Pham, 2022; Suhardianto & Leung, 2020). This finding confirms that excessive work pressure on auditors can lead to their distraction, impairing their ability to focus on critical aspects of continuity assessments. This can result in the neglect of crucial evaluation steps, such as verifying specific transactions or assessing certain risks, contributing to less GCAO accuracy.

Moreover, this finding aligns with the Egyptian context, where auditors often face significant pressures due to high workloads, tight deadlines, and the complexities of local economic conditions. The Egyptian accounting and auditing profession is increasingly challenged by rapid regulatory changes and a dynamic market environment, which can exacerbate work-related stress. This context is further complicated by limited resources and varying levels of organizational support, making it difficult for auditors to maintain focus and accuracy in their assessments. This finding highlights the need for improved support systems and workload management within the Egyptian auditing context.

The adequacy of the hypothesized path analysis model (Model 4) was evaluated through the assessment of several established goodness-of-fit indices. Specifically, the following indices were employed: the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The chi-square test yielded a statistically non-significant p-value of 0.988 (p > 0.05). This non-significant result suggests that the observed data do not deviate significantly from the model-implied covariance matrix, indicating model-data consistency rather than definitive proof of model validity (H. Li et al., 2025). The SRMR value was found to be below the conventionally accepted threshold of 0.08 (SRMR < 0.08), and the RMSEA value was also within acceptable limits (RMSEA < 0.000). Notably, the TLI achieved a perfect value of 1, while the CFI also indicated an excellent model fit with a value of 1 (>0.90). Taken together, these results provide strong evidence of a robust fit between the hypothesized model and the empirical data. The model’s R² values ranged from 0.0185.

Finally, concerning the direct, indirect, and total effect of AWS on the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO (H4), we used path analysis in IBM SPSS Amos 26. Three paths were analyzed: the direct relationship between firm complexity and opinion accuracy, the relationship between firm complexity and AWS, and the relationship between AWS and opinion accuracy. Panel C of Table 5 presents the results of the path analyses, where the significance of the paths was determined using the bootstrap method. The findings revealed a significant positive direct effect of firm complexity on AWS (β = 1.207, p < 0.001), confirming H2. Additionally, a significant negative direct effect of AWS on GCAO was observed (β = −0.044, p < 0.001), supporting H3. Furthermore, a significant negative indirect effect of firm complexity on opinion accuracy was found (β = −0.053, p < 0.000), confirming the mediating role of AWS. Given the significant direct effect of firm complexity on opinion accuracy (β = −0.262, p < 0.000), we conclude that AWS mediates the relationship between firm complexity and opinion accuracy, and, hence, H4 is accepted.

5.5. Robustness Checks

Using Alternative Measures of Main Variables

We examined the robustness of the findings by using alternative measures for the independent variable (firm complexity) and the mediating variable (AWS). We re-ran the research models with alternative measures of the variables (Asnaashari et al., 2023). ROE ratio was employed as an alternative measure of firm complexity (Khan et al., 2023). Additionally, the natural logarithm of the total assets of all clients for each year, regardless of the number of auditors, was utilized as an alternative indicator of AWS (Winoto & Harindahyani, 2021).

Sensitivity analyses produced consistent results, as depicted in Panels A, B, and C of Table 6. These findings corroborated the negative relationship between firm complexity and GCAO (H1). Moreover, they supported the positive association between firm complexity and AWS (H2). Additionally, they confirmed the negative relationship between AWS and GCAO (H3). Lastly, when examining AWS as a mediating variable (H4), these findings ensured its mediating role in the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO.

Table 6.

Alternative measurement of firm complexity and auditors’ work stress.

6. Conclusions

This study examines the direct and indirect influences of firm complexity on the accuracy of auditors’ assessments of a firm’s ability to continue operating, as well as the mediating role of auditor stress in this relationship for Egyptian listed firms. The primary analysis revealed that firm complexity is significantly and negatively associated with the accuracy of these assessments. Additionally, complex firms are associated with higher levels of AWS. Moreover, higher AWS is linked to a decrease in the accuracy of assessments regarding a firm’s ongoing viability. Finally, the current study finds that AWS mediates the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy. The findings remained robust even after conducting sensitivity analyses with alternative measures, further solidifying the overall conclusions.

This study contributes to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on how AWS mediates the relationship between firm complexity and GCAO accuracy. Our research emphasized the impact of organizational factors on audit quality, shedding light on the psychological pressures auditors face in complex environments. It underscored the significance of managing AWS to improve the reliability of financial reporting. These findings have implications for future research and practical strategies for audit firms and policymakers, as follows.

The findings of our study have significant implications for auditing firms, policymakers, and investors, highlighting the necessity for strategies to alleviate AWS. For auditing firms, this study highlights the importance of recognizing and addressing stress among auditors, especially in complex organizations. Implementing training programs and stress management initiatives and fostering supportive work environments can help auditors to more effectively handle the pressures of their roles, potentially leading to more accurate audit judgments. For policymakers, the current results indicate a need for guidelines or regulations that promote auditor well-being. Establishing standards for workload management and stress reduction in auditing practices could enhance overall audit quality and financial reporting reliability. For investors, it is crucial to recognize the potential effects of firm complexity and AWS on GCAO accuracy. This awareness may shape their investment decisions, as understanding these factors can aid in assessing a firm’s financial reporting quality.

However, our study has some limitations. Firstly, the study period is confined to 2017–2023, potentially limiting its generalizability to other timeframes. Secondly, this study focused solely on non-financial firms listed on the Egyptian Stock Exchange, excluding unlisted firms, foreign firms, and financial institutions. Thirdly, the study addressed the impact of firm complexity on GCAO accuracy by focusing on annual financial statement audits, neglecting limited reviews on interim (quarterly) financial statements. Therefore, future research avenues should encompass examining the influence of firm complexity and auditor stress on GCAO accuracy across diverse contexts (e.g., different economies and sectors), evaluating the efficacy of stress management interventions, and exploring the potential for technology and artificial intelligence to mitigate these challenges and enhance audit quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and O.A.; funding acquisition, A.D.; methodology, S.S. and O.A.; project administration, S.S. and A.D.; writing—original draft, S.S. and O.A.; writing—review and editing, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prince Sultan University for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abouelela, O., Diab, A., & Saleh, S. (2025). The determinants of the relationship between auditor tenure and audit report lag: Evidence from an emerging market. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2444553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzali, A., Afzali, M., & Ittonen, K. (2024). Distracted auditors, audit effort, and earnings quality. Accounting Forum, 48, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsheikh, A. H., & Alsheikh, W. H. (2023). Does audit committee busyness impact audit report lag? International Journal of Financial Studies, 11(1), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, I., Khelil, I., El Ammari, A., & Khlif, H. (2023). Money laundering and infrastructure quality: The moderating effect of the strength of auditing and reporting standards. Pacific Accounting Review, 35(2), 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiruddin, A. (2019). Mediating effect of work stress on the influence of time pressure, work–family conflict and role ambiguity on audit quality reduction behavior. International Journal of Law and Management, 61(2), 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschauer, E., & Quick, R. (2024). Implementing shared service centres in Big 4 audit firms: An exploratory study guided by institutional theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 37(9), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnaashari, H., Safarzadeh, M. H., Kheirollahi, A., & Hashemi, S. (2023). The effect of auditors’ work stress and client participation on audit quality in the COVID-19 era. Journal of Facilities Management, 21(4), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadallah, A. A., & Elsaid, H. M. (2020). Investigating the impact of macro-economic changes on auditors’ assessments of audit risk: A field study. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 21(3), 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahtiar, A., Meidawati, N., Setyono, P., Putri, N. R., & Hamdani, R. (2021). Determinants of going concern audit opinion: An empirical study in Indonesia. Jurnal Akuntansi dan Auditing Indonesia, 25(2), 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barinov, A., Park, S. S., & Yıldızhan, Ç. (2024). Firm complexity and post-earnings announcement drift. Review of Accounting Studies, 29(1), 527–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, E. S., Hatfield, R. C., & Houston, R. W. (2022). The effect of staff auditor reputation on audit quality enhancing actions. The Accounting Review, 97(1), 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Z., Elemes, A., Hope, O. K., & Yoon, A. S. (2024). Audit-firm profitability: Determinants and implications for audit outcomes. European Accounting Review, 33(4), 1369–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L., Fogel-Yaari, H., & Zhang, P. (2024). The estimated propensity to issue going concern audit reports and audit quality. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 39(2), 589–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brabander, C. J., & Martens, R. L. (2014). Towards a unified theory of task-specific motivation. Educational Research Review, 11, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldyasty, M. M., & Elamer, A. A. (2023). Audit (or) type and audit quality in emerging markets: Evidence from explicit vs. implicit restatements. Review of Accounting and Finance, 22(4), 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghaly, M., Basuony, M. A., Noureldin, N., & Hegazy, K. (2024). The antecedents of COVID-19 contagion on quality of audit evidence in Egypt. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 14(4), 717–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyk, A., Hodson, J., Khimich, N., & Fedyk, T. (2022). Is artificial intelligence improving the audit process? Review of Accounting Studies, 27(3), 938–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, M. A., Gold, A., & Wallage, P. (2024). Practitioner perspectives on going concern opinion research and suggestions for further study: Part 1—Outcomes and consequences. Accounting Horizons, 38(2), 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghattas, P., Soobaroyen, T., & Marnet, O. (2021). Charting the development of the Egyptian accounting profession (1946–2016): An analysis of the State-Profession dynamics. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 78, 102159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontara, H., Khelil, I., & Khlif, H. (2023). The association between internal control quality and audit report lag in the French setting: The moderating effect of family directors. Journal of Family Business Management, 13(2), 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hana, H., & Triani, N. N. A. (2024). The effect of company characteristics and audit firm on going concern audit opinion issued by audit firm. Journal of Economic, Bussines and Accounting (COSTING), 7(6), 5404–5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, T., Kusumaningtyas, M., Pratiwi, R., Suryanto, E., & Manurung, H. (2023). The influence of audit quality, profitability, liquidity, solvency on going concern audit opinions: A literature review. Jurnal Ilmiah Manajemen Kesatuan, 11(3), 783–790. [Google Scholar]

- Hutagalung, M., Hutagalung, M. T., Afrielza, O., Ndraha, P. A. Y., & Deliana, D. (2024). The influence of previous year audit opinions, company growth and leverage on going concern audit opinions. Prosiding Simposium Ilmiah Akuntansi, 1(1), 935–939. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, D. P., Andiola, L. M., & Hurley, P. J. (2024). Surviving busy season: Using the job demands-resources model to investigate coping mechanisms. Contemporary Accounting Research, 41, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal Hassan, M. (2008). The development of accounting regulations in Egypt: Legitimating the International Accounting Standards. Managerial Auditing Journal, 23(5), 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesimli, I., Karalar, S., & Tasdemir, Ö. (2018). Auditor stress: Literature review and classification. In Sustainability and social responsibility of accountability reporting systems: A global approach (pp. 317–346). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F., Abdul-Hamid, M. A. B., Fauzi Saidin, S., & Hussain, S. (2023). Organizational complexity and audit report lag in GCC economies: The moderating role of audit quality. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 21(5), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelil, I., Guidara, A., & Khlif, H. (2023). The effect of the strength of auditing and reporting standards on infrastructure quality in Africa: Do ethical behaviour of firms and judicial independence matter? Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, 28(1), 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Li, K. Y., Hu, X. R., Hong, X., He, Y. T., Xiong, H. W., & Zhang, Y. L. (2025). Development and validation of the Information Literacy Measurement Scale (ILMS-34) in Chinese public health practitioners. BMC Medical Education, 25(1), 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X., & Sun, L. (2024). High-Quality auditor presence and informational influence: Evidence from firm investment decisions. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 43(2), 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H. J., & Mali, D. (2024). An analysis of the effect of audit effort (hours) on stock price volatility: Evidence of increasing demand reducing uncertainty. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 21(3), 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, T., & McDonald, B. (2023). Measuring firm complexity. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 58(3), 2487–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, A., & Darwis, S. S. (2023). The Psychological impact of work stress on auditors: Exploring determinants and consequences. Journal for ReAttach Therapy and Developmental Diversities, 6(7s), 567–581. Available online: https://jrtdd.com/index.php/journal/article/view/833 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Moez, D. (2024). Does managerial power explain the association between agency costs and firm value? The French Case. International Journal of Financial Studies, 12(3), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Sanusi, Z., Iskandar, T. M., Monroe, G. S., & Saleh, N. M. (2018). Effects of goal orientation, self-efficacy and task complexity on the audit judgement performance of Malaysian auditors. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(1), 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K., & Smith, A. P. (2023). Psychosocial work conditions as determinants of well-being in Jamaican police officers: The mediating role of perceived job stress and job satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nworie, G. O., & Obi, G. U. (2024). Audit firm physiognomies: A contrivance for mitigating corporate failures in listed consumer goods firms in Nigeria. IIARD International Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 10(5), 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ombati, R. M., & Karuti, J. K. (2024). Assessment of the influence of audit plan on the performance of internal auditors in the government ministries in Kenya. International Journal of Public Administration and Management Research, 10(4), 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Peytcheva, M. (2014). Professional skepticism and auditor cognitive performance in a hypothesis-testing task. Managerial Auditing Journal, 29(1), 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D. H. (2022). Determinants of going-concern audit opinions: Evidence from Vietnam stock exchange-listed companies. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q. T., Tan Tran, T. G., Pham, T. N. B., & Ta, L. (2022). Work pressure, job satisfaction and auditor turnover: Evidence from Vietnam. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, O. C., Charris, N. N., Perez, E. B., Tovar, O. O., & Cantillo, I. F. C. (2023). Forensic audit: A case of automotive company, legal and accounting aspect. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 11(12), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proho, M. (2023). Going concern assessment: A literature review. Journal of Forensic Accounting Profession, 3(2), 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S. A. (2023). Auditor’s effort following the implementation of 2015 revised Egyptian Accounting Standards: An evidence from the nonfinancial listed firms on the Egyptian Stock Exchange. Alexandria Journal of Accounting Research, 7(3), 131–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M., Seyyed, F., & Farhangdoust, S. (2020). The impact of personal characteristics, quality of working life and psychological well-being on job burnout among Iranian external auditors. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior, 23(3), 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W., Connelly, B. L., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2017). External corporate governance and financial fraud: Cognitive evaluation theory insights on agency theory prescriptions. Strategic Management Journal, 38(6), 1268–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahaan, L. E. J., Sihombing, J. T., Nasution, S. A., & Ginting, W. A. (2024). The influence of company size, profitability, solvency, current ratio, and capital structure on going concern audit opinions in consumer sector companies listed on the Indonesia stock exchange (BEI) 2019–2022. International Journal of Economics, Business and Innovation Research, 3(03), 339–358. [Google Scholar]

- Suhardianto, N., & Leung, S. C. (2020). Workload stress and conservatism: An audit perspective. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebkhah, Z. (2020). The relationship between auditor’s stress with audit quality and internal control weakness. Iranian Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 4(1), 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiron-Tudor, A., & Deliu, D. (2022). Reflections on the human-algorithm complex duality perspectives in the auditing process. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 19(3), 255–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, A., & Anandarajan, A. (2004). Dimensions of pressures faced by auditors and its impact on auditors’ independence: A comparative study of the USA and Australia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 19(1), 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthman, A. B., Salami, A. A., & Ajape, K. M. (2022). Impact of auditor industry specialization on the audit quality of listed non-financial firms in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Risk and Insurance, 12(1), 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hau, N., Hai, P. T., Diep, N. N., & Giang, H. H. (2023). Determining factors and the mediating effects of work stress to dysfunctional audit behaviors among Vietnamese auditors. Calitatea, 24(193), 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Chiu, T., & Kogan, A. (2024). The effects of COVID-19 pandemic and auditor-client geographic proximity on auditors’ going concern opinions. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 21(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winoto, C. O., & Harindahyani, S. (2021). The effect of auditor’s work stress on audit quality of listed companies in Indonesia. Journal of Economics, Business, and Accountancy Ventura, 23(3), 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2023). World development indicators: Inflation, consumer prices (annual %). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FP.CPI.TOTL.ZG (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Yan, H., & Xie, S. (2016). How does auditors’ work stress affect audit quality? Empirical evidence from the Chinese stock market. China Journal of Accounting Research, 9(4), 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Simnett, R., & Carson, E. (2022). Auditors’ propensity and accuracy in issuing going concern modified audit opinions for charities. Accounting & Finance, 62, 1273–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).