2.1. Inventory Management and Financial Reporting Quality

In the last two decades, supply chain management has evolved from an operational support function into a core strategic discipline driving competitive advantage and financial performance (

Mentzer, 2004;

Shi & Yu, 2013). SCM encompasses the integrated coordination of physical, informational, and financial flows across organizations. At the heart of this system lies inventory management, a critical mechanism for aligning supply with demand and ensuring operational continuity.

Beyond its operational importance, inventory performance is increasingly recognized for its financial implications. Efficient management of inventory not only optimizes costs and reduces working capital but may also limit managerial incentives or opportunities for earnings manipulation. This opens the door to a growing stream of interdisciplinary research investigating the connection between physical flow optimization and earnings management (EM).

A new stream of empirical literature has emerged examining how operational efficiency affects managerial discretion in earnings reporting.

Lanier et al. (

2019) demonstrate that firms with greater supply chain power tend to engage more in real earnings management (e.g., overproduction) to meet financial targets.

Comiran and Siriviriyakul (

2022) show that excessive inventory accumulation may signal future write-downs and earnings smoothing behaviors. Some authors suggest that supply chain digitalization enhances transparency and discourages EM (

Autore et al., 2024;

Bafghi & Aldin, 2024).

Suhanda and Firmansyah (

2020) explore SCM as a mediating factor reducing the volatility and opacity associated with EM. These studies converge on the idea that firms with robust SCM, particularly in inventory practices, exhibit less need or ability to engage in earnings manipulation.

From a theoretical standpoint, inventory management interacts with earnings management through both agency theory and information asymmetry perspectives.

Baldenius and Reichelstein (

2000) show that historical cost-based residual income measures can yield optimal incentives for managers to manage inventory efficiently, especially under the LIFO valuation method. However, when compensation is tied to short-term accounting results, managers may intentionally manipulate production or inventory levels to influence reported earnings (

Wu & Lai, 2022). This behavior is consistent with the agency problem, wherein information asymmetry allows managers to act in their own interest rather than that of shareholders.

Moreover, as

Friebel and Guriev (

2005) highlight, such opportunistic manipulation within internal hierarchies can distort incentives, encourage rent-seeking behavior, and reduce overall efficiency.

Crocker and Slemrod (

2007) further note that because earnings-based contracts are imperfectly informative, some level of earnings management might emerge as an equilibrium response to balance contractual efficiency and truthful reporting. In this context, inventory decisions play a dual role: they are both operational levers for cost control and potential instruments for accounting discretion.

While much of the literature highlights the connection between inventory practices and real earnings management, inventory management also has a direct and theoretically grounded influence on accrual-based earnings management. Accruals related to inventory—such as allowances for obsolescence, adjustments to net realizable value, and cost allocation between ending inventory and cost of goods sold—require managerial judgment and rely heavily on the quality of underlying inventory data. When inventory systems are inefficient, fragmented, or poorly monitored, managers face greater discretion in estimating these accruals, creating opportunities to manipulate reported earnings through valuation adjustments rather than through real operating actions.

Efficient inventory management constrains this discretion in several ways. First, firms with high-quality inventory processes (e.g., accurate records, timely updates, strong service levels, low discrepancies) generate more reliable operational data, which reduces estimation uncertainty for accruals such as write-downs, provisions, and overhead allocations. Second, transparent inventory flows strengthen the audit trail available to internal and external auditors, making it more difficult for managers to justify aggressive or opportunistic accrual adjustments. Third, robust inventory discipline limits the buildup of obsolete or slow-moving items, reducing situations in which managers might strategically time impairments to smooth earnings. In this sense, inventory performance acts as a governance mechanism that improves accrual accuracy and reduces the potential for discretionary financial reporting.

Overall, the literature suggests a complex yet significant relationship between inventory efficiency and earnings quality. Efficient inventory management improves operational transparency and reduces the scope for accrual-based manipulation by strengthening data accuracy, reducing estimation uncertainty, and limiting opportunities for discretionary valuation. Conversely, poor or opportunistic inventory practices can conceal inefficiencies and distort financial outcomes. This dual nature justifies examining inventory metrics—such as turnover ratio, service level, and coverage rate—not only as operational indicators but also as potential determinants of accrual-based earnings management, particularly in emerging market contexts where monitoring mechanisms and digital infrastructures remain uneven.

2.2. Research Hypotheses

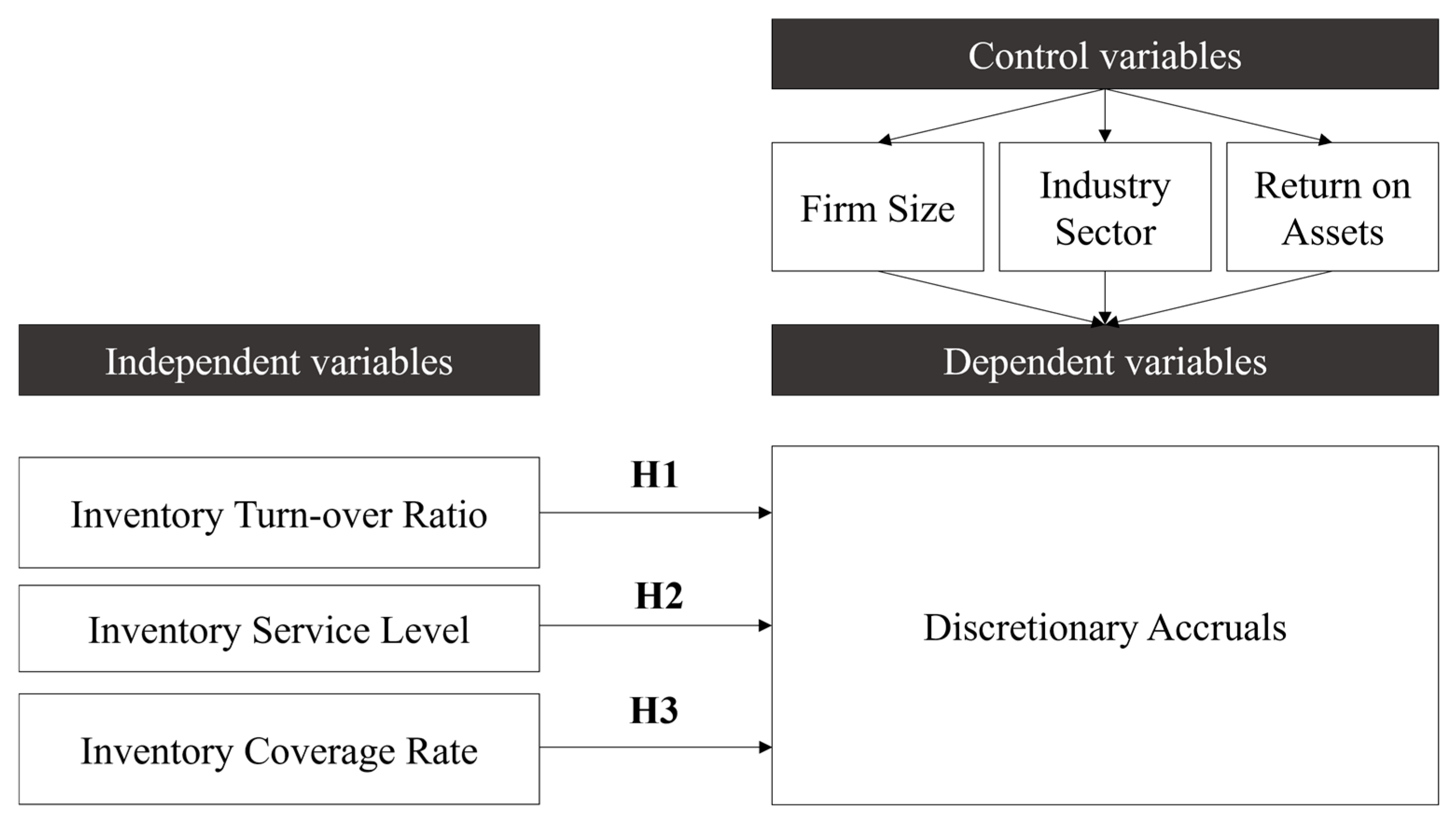

This study aims to investigate whether firms’ inventory management practices—viewed as key indicators of supply chain efficiency—are associated with lower levels of earnings management. Efficient inventory control is central to financial transparency be-cause inventory valuation directly affects cost of goods sold and, consequently, reported earnings. Poor or manipulative inventory practices may distort accruals and misrepresent financial performance. Drawing on prior literature in accounting, operations, and supply chain management, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H1: A higher inventory turnover ratio (ITR) is negatively associated with discretionary accruals.

The Inventory Turnover Ratio (ITR) captures how quickly a firm converts inventory into sales. A high ITR indicates efficient procurement planning, rapid stock rotation, and minimal obsolete or slow-moving items. These operational conditions directly reduce the areas of accounting that depend heavily on managerial judgment—such as provisions for inventory obsolescence, net realizable value (NRV) assessments, and discretionary allocations of production overheads.

Prior research demonstrates that inventory accounts are among the most sensitive to accrual manipulation.

Thomas and Zhang (

2002) show that inventory variations are strongly associated with discretionary accruals because managers can exploit valuation flexibility to influence reported earnings. When turnover is high, however, inventory remains close to physical flows and actual demand, limiting managers’ ability to justify subjective adjustments (

Demeter & Matyusz, 2011).

From an agency theory perspective (

Crocker & Slemrod, 2007), managers have incentives to manipulate earnings when operations are inefficient or costs rise. However, firms with lean and transparent inventory systems face fewer opportunities for such manipulation because inventory-related estimates—such as obsolescence reserves or production cost allocations—become more closely tied to real transactions.

Similarly,

Dichev et al. (

2013) have previously argued that rapid inventory rotation improves the objectivity of valuation estimates and reduces the informational gaps that allow discretionary manipulation. More recent evidence supports this view:

Baboukardos and Rimmel (

2016) find that transparent and efficient inventory practices improve the reliability of accounting estimates by reducing uncertainty around obsolescence and NRV testing. From a supply chain perspective,

Lanier et al. (

2019) and

Anderson and Dekker (

2009) show that operational efficiency and integrated SCM systems enhance the accuracy of cost allocations and reduce overall accounting discretion.

Taken together, this literature suggests that firms with high inventory turnover face fewer estimation-based choices—precisely the mechanisms through which accrual-based earnings management typically occurs. Efficient turnover reduces slow-moving stock and valuation uncertainty, thereby limiting the opportunities for managers to manipulate accruals.

H2: A higher inventory service level (ISL) is negatively associated with discretionary accruals.

The Inventory Service Level (ISL) reflects a firm’s ability to satisfy customer demand without delays or stockouts. High service levels typically arise from accurate forecasting, synchronized purchasing and production activities, robust internal information systems, and real-time tracking of inventory movements (

Cho et al., 2012). These operational features improve the precision of inventory records and reduce discrepancies between physical flows and accounting balances.

Because inventory valuation is one of the most estimate-dependent areas of financial reporting, better operational accuracy directly limits the scope for managerial discretion. High ISL reduces the need for subjective adjustments related to net realizable value testing, shrinkage estimates, overhead capitalization, and work-in-progress valuation. In other words, when inventory operations function reliably, managers have fewer opportunities to manipulate accruals through judgment-based estimates (

Lanier et al., 2019;

Suhanda & Firmansyah, 2020).

From a transparency and legitimacy perspective (

Breuer, 2021;

Chen et al., 2010), firms with efficient service levels tend to maintain better data integration and performance monitoring systems, reducing the informational asymmetry between management and stakeholders.

Prior research supports this mechanism.

Hribar et al. (

2014) show that real-time operational information improves the accuracy of financial reporting and reduces discretionary accruals by narrowing the gap between operational data and accounting estimates. Similarly,

Bushman et al. (

2004) highlight that strong internal information systems constrain managerial discretion by reducing informational asymmetry and increasing the verifiability of reported figures. Field-evidence from

Dichev et al. (

2013) reinforce that firms with disciplined operational controls exhibit lower levels of accrual manipulation because managers cannot easily justify subjective accounting adjustments. In the supply chain domain,

Gao et al. (

2022) find that supply chain integration and visibility enhance transparency and reduce earnings management, demonstrating that operational coordination has direct implications for accounting quality.

Thus, these insights indicate that high ISL serves as a non-financial indicator of internal control strength and reporting reliability. By enhancing data accuracy and reducing estimation uncertainty, superior service levels limit managers’ ability to rely on discretionary accruals to alter financial results.

H3: A higher inventory coverage rate (ICR) is positively associated with discretionary accruals.

The inventory coverage rate (ICR) represents the average number of days or months that inventory remains in stock before being sold. It reflects how long capital is tied up in inventory and how efficiently a company balances supply and demand (

Cho et al., 2012).

A high ICR generally indicates slow-moving or excess inventory, which increases managerial discretion in valuation because these items require more subjective assessments. This longer holding periods heighten uncertainty related to potential obsolescence, NRV measurement, the timing of write-downs, and the estimation of impairment provisions—precisely the areas where accrual-based earnings management typically occurs.

Because inventory valuation relies extensively on judgment, high ICR creates conditions that facilitate opportunistic financial reporting. Managers can delay or accelerate write-downs, overstate the recoverable value of outdated goods, or adjust provisions to meet short-term earnings benchmarks. These accounting choices do not require changes in real operations; they are purely accrual-based and allow managers to influence earnings without altering underlying economic performance.

Prior studies support this mechanism.

Thomas and Zhang (

2002) identify inventory as one of the most frequent channels for accrual manipulation, given the flexibility embedded in valuation rules.

Galdi and Pereira (

2007) further show that firms with slow-moving inventories face greater opportunities to manipulate accruals because the valuation of aged stock inherently requires discretionary judgments. Empirical evidence from

Cook et al. (

2012) demonstrates that managers actively use inventory valuation discretion—including NRV assessments and impairment timing—to manage reported earnings.

Similarly,

Galdi and Johnson (

2021) highlight that inventory accounting choices and valuation methods (e.g., FIFO vs. weighted average) can significantly influence reported profits and accruals, particularly in manufacturing-intensive industries. Longer inventory holding periods amplify estimation uncertainty related to obsolescence and net realizable value, thereby increasing opportunities for discretionary accrual manipulation.

From an agency and cost-of-capital perspective, such behavior may provide short-term earnings benefits but deteriorates long-term performance, as excess inventory leads to higher holding costs and potential impairments (

Friebel & Guriev, 2005;

Wu & Lai, 2022).

More broadly,

Srinidhi et al. (

2011) highlight that, assets requiring high levels of estimation provide the greatest scope for accrual-based manipulation, reinforcing the idea that slow-moving inventory invites subjective accounting adjustments.

Taken together, these studies propound that a high ICR increases managerial latitude in valuation decisions, thereby expanding the opportunities for accrual-based earnings management. In contrast to firms with efficient inventory turnover or high service levels, firms with prolonged inventory holding periods face greater uncertainty and heavier reliance on accounting judgment, making accrual manipulation more likely.

To isolate the effect of inventory metrics on earnings management, the study includes a set of parsimonious control variables that are consistently used in the earnings management literature and theoretically justified in the Moroccan context. Given the relatively small sample size of Moroccan listed firms, the inclusion of too many controls could reduce statistical power or introduce multicollinearity. Therefore, we restrict our controls to a well-established core set capturing firm size, industry characteristics, and financial performance—three dimensions repeatedly shown to influence discretionary accruals.

Firm size is one of the most widely used controls in earnings management research because it captures several economic and governance attributes that directly affect managerial discretion (

Siregar & Utama, 2008;

Swastika, 2013;

Bellari, 2024a). Larger firms typically benefit from more sophisticated internal controls, higher analyst coverage, and stronger audit quality, all of which reduce opportunities for aggressive accrual manipulation. At the same time, larger firms often have more complex operations and diversified activities, which may increase estimation uncertainty and create room for discretionary accounting choices. This dual effect makes firm size a fundamental determinant of earnings quality. Controlling for size ensures that the effect attributed to inventory performance is not confounded with differences in monitoring, internal control structures, or information environments that naturally vary across small and large firms.

Industry sector is included because inventory cycles, valuation practices, and cost structures differ substantially across industries, particularly between manufacturing, retail, and service-oriented firms (

Breuer, 2021;

Moser et al., 2017;

Bellari, 2024a). These differences affect both operational drivers of inventory metrics and the accounting rules governing cost allocations or write-downs. For instance, industries with long production cycles (e.g., chemicals, metallurgy) face higher uncertainty in estimating inventory obsolescence, while fast-moving retail industries tend to exhibit frequent stock rotations and more standardized inventory valuation practices. These heterogeneities directly influence the baseline level of accruals associated with inventory. Including industry effects helps ensure that the relationship between inventory performance and discretionary accruals is not driven by structural sectoral differences. This is especially important in the Moroccan setting, where industrial composition varies significantly across listed firms.

ROA is incorporated following

Kothari et al. (

2005), who demonstrate that discretionary accrual models can be biased if performance differences across firms are not controlled for. Earnings management is often correlated with profitability: high-performing firms may have fewer incentives to inflate earnings, whereas poorly performing firms may resort to accrual manipulation to meet benchmarks or avoid reporting losses. Controlling for ROA helps mitigate performance-related bias in the estimation of discretionary accruals and ensures that variations in accruals are not simply reflecting differences in underlying economic performance. This adjustment is essential in emerging markets, where profitability volatility is higher and managerial incentives tied to performance are more pronounced.

Taken together, these three variables—firm size, industry sector, and profitability—represent the most theoretically relevant and empirically validated determinants of earnings management across the accounting literature. Given the limited number of Moroccan listed firms and the risk of overfitting, the model is intentionally restricted to this concise set of controls to maintain statistical robustness while capturing the principal sources of variation in discretionary accruals.