AI-Driven Business Model Innovation and TRIAD-AI in South Asian SMEs: Comparative Insights and Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identify institutional, technical, and financial barriers and policy-related challenges affecting AI-driven BMI in South Asian SMEs;

- Analyse the state of AI adoption BMI across SMEs in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka;

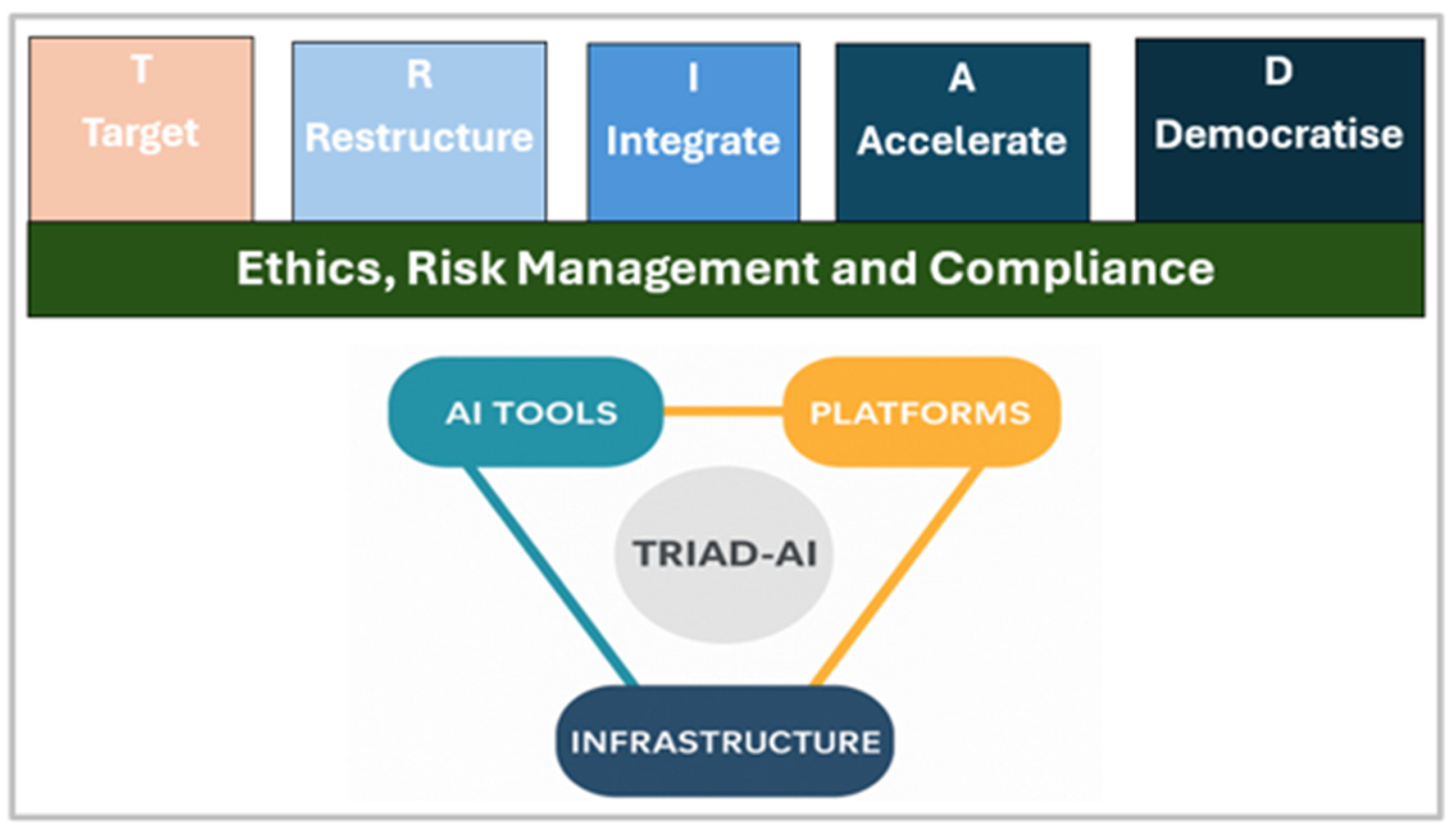

- Develop the TRIAD-AI framework that integrates global best practices with regional SME contexts to enhance financial sustainability, risk management, and competitiveness;

- Conceptually evaluate the potential implications of the TRIAD-AI framework for SME competitiveness, financial resilience, and responsible AI adoption in South Asia.

2. Literature Reviews

2.1. Bangladesh

2.2. India

2.3. Pakistan

2.4. Sri Lanka

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Type of Study

3.2. Approach

3.3. Selection of Countries

3.4. Selection Criteria

3.5. Data Sources

3.6. Framework Validation

3.7. Limitations

4. Theoretical Grounding

5. Proposed Framework: TRIAD-AI for South Asian SMEs

5.1. Comparison with Existing Frameworks

5.2. Key Enablers of the TRIAD-AI Framework

- Institutional Environment—For AI adoption, national policies, infrastructure, compliance with global AI standards, and government support are essential. China’s 2017 AI development Plan, Estonia’s digital governance strategy, and Singapore’s AI roadmaps serve as exemplary models for South Asian countries.

- Organizational Capacity—For the implementation of AI adoption, SMEs require adequate digital literacy, leadership commitment, and internal resources to restructure business operations and integrate AI. Supportive policies will fail if these capabilities are absent. Singapore’s SMEs Go Digital programme, which offers consultancy services, vouchers, and capability-building training, and China’s state-backed incubators, which offer funding and organisational capacity support, represent strong practices that can be applied for South Asia.

- External Networks—Peer learning, accelerators, incentives, and partnerships with universities and large firms are critical for achieving affordable expertise and reducing barriers to entry. AI Singapore, which serves as a national R&D hub connecting universities, government, and SMEs in collaborative projects, and Estonia’s startup- fostering networks, which provide scalable platforms, offer strong exemplars for South Asian countries.

- These enablers also respond to the human-capital gaps identified in the comparative analysis, particularly widespread skills shortages, uneven digital literacy, and limited organisational readiness across SMEs in South Asia. The five pillars of the TRIAD-AI framework support capacity building by enabling context-specific targeting, operational redesign, AI integration, scalable adoption, and inclusive participation, and they can be customised to reflect local, regional and national SME needs. Together, these elements ensure that the framework addresses not only institutional and infrastructural gaps but also the human–capital constraints that hinder SME participation in AI-driven BMI.

6. Operationalising the TRIAD-AI Framework

6.1. Embedding Ethics and Compliance in TRIAD-AI

6.2. Managing Financial and Operational Risks in TRIAD-AI

7. Results

7.1. Country-Specific Results

- India is the most prepared South Asian nation for AI adoption by SMEs, supported by strong regional start-up ecosystems (e.g., Bengaluru, Delhi, and Hyderabad) and comprehensive national policy initiatives. However, the country faces a national divide in such development. While urban SMEs use AI for forecasting, logistics, analytics, and customer management, many rural firms still struggle to access even basic digital infrastructure.

- Bangladesh is in an early stage of AI adoption. Although the country’s policy emphasises R&D, skills development, and start-up acceleration, progress in these areas is hampered by the absence of a unified AI policy and by fragmented implementation mechanisms. SMEs in microfinance, agricultural technology (AgriTech), and education technology (EdTech) mainly use AI applications for BMI, but these remain pilot-scale and vendor-dependent. Infrastructure bottlenecks, unreliable power supply, skill shortages, and limited institutional capacity create barriers to scalability and long-term resilience.

- Pakistan has recently introduced several initiatives to support AI adoption, including research funding, new AI centres of excellence, and venture support mechanisms. However, the country faces weak digital infrastructure, frequent power disruptions, and a shortage of AI professionals, along with institutional immaturity and policy uncertainty. Collectively, these factors hamper implementation, increase risks, and place sustainability beyond reach.

- Sri Lanka has recently undertaken targeted initiatives such as Scale Up Sri Lanka 2025 to promote AI adoption and has shown notable progress in sectors such as tourism, retail, and manufacturing, where SMEs are using AI for customer analytics and productivity improvement. This progress has been supported by high digital literacy in urban areas. However, economic instability, data-quality issues, and underinvestment in digital infrastructure make widespread adoption difficult.

7.2. Cross Country Patterns and Thematic Insights

- Policy and Governance: India leads with coherent AI policies and strategies, whereas Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka are behind and still developing their AI policies and strategies to support SMEs. Such fragmented policy and governance structures slow down AI-driven BMI and hinder the adoption of responsible AI standards.

- Infrastructure and Digital Readiness: Digital ecosystems differ significantly across the region. India and Sri Lanka have relatively strong digital infrastructure in their urban areas. On the other hand, Bangladesh and Pakistan, along with rural regions of India, still face challenges related to accessibility, reliable connectivity and the affordability of cloud platforms.

- Economy and Financial Implications: With the integration of AI-driven BMI, urban SMEs in India and Sri Lanka are improving their operations and managing revenue diversification. However, limited financial resilience limits widespread scaling across all South Asian countries.

- Human Capital and Skills: All four countries face AI-related skill gaps, which are the critical bottleneck for the growth of their SMEs, particularly in rural and semi-urban areas.

- Ethics, Risk and Compliance: None of the four South Asian countries possesses a robust regulatory framework comparable to global SME leaders such as China, Estonia, and Singapore. They also face recurring challenges, including ethical risks, data privacy concerns, and inadequate compliance systems.

- Collaboration and Ecosystem Support: South Asian countries lack strong partnerships and coordinated ecosystem support among government, academia, and industry to foster AI-driven BMI. This fragmentation limits shared learning, technology transfer, and innovation scaling.

- Performance Outcomes: Although quantitative metrics vary across countries, the above several patterns point toward potential measurable indicators such as productivity gains, operational efficiency improvements, and strengthened financial resilience, which can be explored in future empirical assessments of AI-driven BMI.

7.3. Framework Derivation

- Weak infrastructure and skill shortages slow SME growth. The Target and Restructure pillars address these gaps by focusing on foundational readiness and capacity building.

- While many SMEs struggle to integrate AI into their daily operations, the Integrate and Accelerate pillars aim to bring digital tools into regular business use and make growth easier to scale.

- Unequal access and weak governance continue to hold many SMEs back. The Democratise pillar therefore focuses on widening participation and keeping the ethical use of AI at the core of development.

- For collaboration and ecosystem support, the Target pillar identifies key actors (e.g., government agencies, institutions and private enterprises); the Restructure pillar designs policy and institutional mechanisms to enable partnerships; the Integrate pillar links SMEs with these key actors to support knowledge exchange and technology transfer; the Accelerate pillar scales successful AI solutions; and the Democratise pillar ensures equitable access to resources and ethical alignment across the SME ecosystem.

8. Implications and Discussion

9. Limitations and Future Directions

10. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AIaaS | AI-as-a-Service |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| BMI | Business Model Innovation |

| DOI | Diffusion of Innovation |

| EU | European Union |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NPL | Natural Language Processing |

| OCR | Optical Character Recognition |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| R&D | Research & Development |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SME | Small and Medium Enterprise |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| TOE | Technology–Organisation–Environment |

| TRIAD | Target, Restructure, Integrate, Accelerate, Democratise |

References

- Agostini, L., Nosella, A., & Filippini, R. (2021). Business model innovation and digital transformation: The moderating effect of digital maturity. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 165, 120518. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M., Hussain, M., & Mir, H. (2024). Developing a legal framework for digital policy: A roadmap for AI regulations in Pakistan. Lahore Policy Review, 5(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Aithal, A., & Aithal, P. S. (2020). Opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence in Indian business sector. International Journal of Applied Engineering and Management Letters (IJAEML), 4(1), 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S., & Khan, M. A. (2020). Digital transformation challenges in Pakistan: A policy perspective. Journal of Information Technology, 35(4), 321–335. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2012). Creating value through business model innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review, 53(3), 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Article 62. (2025). EU artificial intelligence act. Measures for providers and deployers, in particular SMEs, including Start-Ups. Available online: https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/article/62/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2023). The digital transformation of SMEs in Asia and the Pacific. ADB. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Productivity Organization. (2025). Driving SME competitiveness in Sri Lanka: AI-powered productivity solutions. Available online: https://www.apo-tokyo.org/aponews/driving-sme-competitiveness-in-sri-lanka-ai-powered-productivity-solutions/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- ASSOCHAM & CPA Australia. (2025). Business technology report 2024: Indian businesses and AI adoption. CPA Australia in Collaboration with the Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India. Available online: https://www.cpaaustralia.com.au/-/media/project/cpa/corporate/documents/tools-and-resources/business-management/business-management-research/business-technology-report_2024_digital_v1.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Awan, U., Sroufe, R., & Hizam-Hanafiah, M. (2025). Enhancing SME resilience through artificial intelligence and strategic foresight: A framework for sustainable competitiveness. Technology in Society, 81, 102835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badghish, S., & Soomro, Y. A. (2024). Artificial intelligence adoption by SMEs to achieve sustainable business performance: Application of technology-organization-environment framework. Sustainability, 16(5), 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Chambers of Commerce. (2025). Turning point as more SMEs unlock AI: 35% of SMEs now actively using AI technologies. Available online: https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/news/2025/09/turning-point-as-more-smes-unlock-ai/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Business Times. (2025). Pakistan rolls out AI policy to shape digital future. SPH Media Limited. Available online: https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defence Journal. (2025). From vision to reality: Infrastructure challenges in Pakistan’s AI ambitions. Defence Journal Publishers, Karachi, Pakistan. Available online: https://www.defencejournal.com/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Department for Business and Trade. (2025). Small companies are using AI quick ‘wins’ to improve efficiency. The Times. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/small-companies-are-using-ai-to-improve-efficiency-enterprise-network-jhvssm2zm (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Department of Industry, Australia. (2024). AI adoption in Australian businesses—Q4 2024. Available online: https://www.industry.gov.au/news/ai-adoption-australian-businesses-2024-q4 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Dung, L. T., & Dung, T. T. H. (2024). Business model innovation and internationalization in SMEs. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, L., Ismagilova, E., Aarts, G., Coombs, C., Crick, T., Duan, Y., Dwivedi, R., Edwards, J. J. D., Eirug, A., Galanos, V., Ilavarasan, P. V., Janssen, M., Jones, P., Kar, A. K., Kizgin, H., Kronemann, B., Lal, B., Lucini, B., … Williams, M. D. (2021). Artificial intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda. International Journal of Information Management, 57, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Times India. (2025). 23% of Indian businesses implemented AI, 73% to adopt tech in 2025. The Economic Times (ET CFO). Available online: https://cfo.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/cfo-tech/23-indian-businesses-implemented-ai-73-to-adopt-artificial-intelligence-tech-in-2025/117874393 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- European Commission. (2024). Estonia 2024 digital decade country report. Digital strategy—Shaping Europe’s digital future. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/factpages/estonia-2024-digital-decade-country-report (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act). Official Journal of the European Union, L 1689, 12 July 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj/eng (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Fernando, T., & Senanayake, R. (2022). The digital innovation capabilities of Sri Lankan SMEs: Challenges and future directions. South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases, 11(2), 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N. J., & Saebi, T. (2017). Fifteen years of research on business model innovation: How far have we come, and where should we go? Journal of Management, 43(1), 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom (FNF). (2025). Examining AI in low and middle-income countries: Barriers and policy recommendations (Policy Paper). Friedrich Naumann Foundation. Available online: https://www.freiheit.org/sites/default/files/2025-05/fnf-policy-report-ai.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Hale, C. (2025). Many SMBs say they can’t get to grips with AI, need more training. Available online: https://www.techradar.com/pro/many-smbs-say-they-cant-get-to-grips-with-ai-need-more-training (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Hussain, A., & Rizwan, R. (2024). The case for an industrial policy approach to AI sector of Pakistan for growth and autonomy. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAMAI (Internet and Mobile Association of India). (2023). Digital India: Internet penetration report 2023. Available online: https://www.iamai.in/our-initiatives/research (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- ICT Division. (2020). National strategy for artificial intelligence—Bangladesh. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- ICTA. (2025). Empowering SMEs with AI: Highlights from scale up Sri Lanka 2025. Available online: https://www.icta.lk/media/news/empowering-smes-with-ai-highlights-from-scale-up-sri-lanka-2025 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- IFC. (2025). Bangladesh: Country private sector diagnostic. International Finance Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- IMDA. (2025). SMEs go digital—Singapore. Infocomm Media Development Authority. Available online: https://www.imda.gov.sg/how-we-can-help/smes-go-digital (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Jorzik, P., Klein, S. P., Kanbach, D. K., & Kraus, S. (2024). AI-driven business model innovation: A systematic review and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 182, 114764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H., & Chowdhury, S. A. (2021). The role of artificial intelligence in promoting inclusive SME development in Bangladesh (ICT for development working paper series). United Nations Development Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R., Nasir, S., & Akter, S. (2023). Digitization and SME growth in Bangladesh: Opportunities for AI applications. Journal of Development Policy and Practice, 8(1), 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kopka, A., & Fornahl, D. (2024). Artificial intelligence and firm growth—catch-up processes of SMEs through integrating AI into their knowledge bases. Small Business Economics, 62(1), 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., Sharma, P., & Gupta, R. (2022). AI adoption in Indian SMEs: Trends and business impacts. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(4), 1023–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Luu, T. D., & Dung, T. (2024). Business model innovation: A key role in the internationalisation of SMEs in the era of digitalisation. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R., & Pandit, R. (2021). AI-driven startups in India: Government support and entrepreneurial dynamics. Technovation Review India, 14(2), 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- MITRE & USAID. (2022). Small and medium enterprise digitization in Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and India. MITRE. Available online: https://www.mitre.org/news-insights/publication/small-medium-enterprise-digitization-bangladesh-nepal-sri-lanka-india (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- NITI Aayog. (2018). National strategy for artificial intelligence #AIFORALL. Government of India. Available online: https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-03/National-Strategy-for-Artificial-Intelligence.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- NITI Aayog. (2025). AI for viksit bharat: The opportunity for accelerated economic growth. Government of India. Available online: https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2025-09/AI-for-Viksit-Bharat-the-opportunity-for-accelerated-economic-growth.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- OECD. (2019a). Recommendation of the council on artificial intelligence. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Available online: https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0449 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- OECD. (2019b). What are the OECD principles on AI? Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/what-are-the-oecd-principles-on-ai_6ff2a1c4-en.html (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- OECD. (2025). Asia capital markets report 2025: AI innovation facilitators in Asia. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/asia-capital-markets-report-2025_02172cdc-en.html (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Oldemeyer, L., Jede, A., & Teuteberg, F. (2024). Investigation of artificial intelligence in SMEs: A systematic review of the state of the art and the main implementation challenges. Management Review Quarterly, 75, 1185–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakistan Ministry of Information Technology & Telecommunication. (2025). National artificial intelligence policy 2025. Government of Pakistan. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1927634/federal-cabinet-approves-national-ai-policy-2025 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Perera, K., Gunawardana, D., & Pathirana, R. (2023). Exploring the use of artificial intelligence in SMEs in Sri Lanka: An empirical study. Asian Journal of Business and Technology, 6(1), 24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, R.-G., Popa, I.-C., Ciocodeică, D.-F., & Mihălcescu, H. (2025). Modeling AI adoption in SMEs for sustainable innovation: A PLS-SEM approach integrating TAM, UTAUT2, and contextual drivers. Sustainability, 17(15), 6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., & Siddiqui, N. (2022). Digital skills, AI awareness, and business model transformation in Bangladeshi SMEs. Asian Economic Papers, 21(4), 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, T., & Sultana, S. (2023). AI adoption in Bangladeshi SMEs: Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Business and Technology, 18(2), 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, A. (2020). Explainable AI: From black box to glass box. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(1), 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sage. (2025). The AI revolution: Accelerating SME adoption. Sage UK. Available online: https://www.sage.com/en-gb/company/digital-newsroom/2025/02/10/the-ai-revolution-accelerating-smes (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Salesforce. (2025). 91% of SMEs using AI report revenue boosts—While 87% scale operations faster than manual competitors. SME Scale. Available online: https://smescale.com/91-of-smes-using-ai-report-revenue-boosts-while-87-scale-operations-faster-than-manual-competitors (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Saxena, S., & Kumar, V. (2023). AI-as-a-service adoption among Indian SMEs: Opportunities and challenges. International Journal of AI and Business, 8(2), 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Schwaeke, J., Peters, A., Kanbach, D. K., Kraus, S., & Jones, P. (2024). The new normal: The status quo of AI adoption in SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 63(3), 1297–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarra-Blasco, A., Tomàs-Porres, J., & Teruel, M. (2025). AI, robots and innovation in European SMEs. Small Business Economics, 65, 719–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, M. S., Ghazi, A. W., & Yasmeen, R. (2021). Artificial intelligence and SME performance in Pakistan: A conceptual framework. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 15(2), 343–359. [Google Scholar]

- Shaik, A. S., Alshibani, S. M., Jain, G., Gupta, B., & Mehrottra, A. (2023). Artificial intelligence-driven strategic business model innovations in small- and medium-sized enterprises: Insights on technological and strategic enablers for carbon neutral businesses. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(1), 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A., Simske, S. J., & Chong, E. K. P. (2024). Evaluating artificial intelligence models for resource allocation in circular economy digital marketplace. Sustainability, 16(23), 10601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotamaa, T., Reiman, A., & Kauppila, O. (2024). Manufacturing SME risk management in the era of digitalisation and artificial intelligence: A systematic literature review. Continuity & Resilience Review, 6(2), 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2010). Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2018). Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Planning, 51(1), 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Times. (2024). Small companies are using AI for quick efficiency gains. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Tornatzky, L. G., & Fleischer, M. (1990). The processes of technological innovation. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wamba Taguimdje, S. L., Fosso Wamba, S., Kala Kamdjoug, J. R., & Tchatchouang Wanko, C. E. (2020). Influence of AI on firm performance: Evidence from SMEs. Business Process Management Journal, 26(7), 1819–1835. [Google Scholar]

- Wijesinghe, C., & Jayathilaka, R. (2021). Artificial intelligence in Sri Lanka: Policy, practice, and potential. Digital South Asia Report Series, 2(3), 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2021). World development report 2021: Data for better lives. World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2021 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- World Bank. (2024). Leveraging artificial intelligence for inclusive growth in emerging markets. World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/digitaldevelopment (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- World Economic Forum. (2024). AI Governance Alliance unveils inaugural report on equitable AI Strategies. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/01/ai-governance-alliance-debut-report-equitable-ai-advancement (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Zavodna, L. S., Überwimmer, M., & Frankus, E. (2024). Barriers to the implementation of artificial intelligence in small and medium-sized enterprises: Pilot study. Journal of Economics and Management, 46(1), 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Bangladesh | India | Pakistan | Sri Lanka |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Govt. Policy & Support | R&D, skills development, startup acceleration; no unified national AI policy | National AI Policy 2025, IndiaAI Mission, state-level AI initiatives, startup support | National AI Policy 2025; AI centres of excellence; funding support | Scale Up Sri Lanka 2025, government programs supporting AI adoption |

| SME AI Adoption Progress | Microfinance, AgriTech, ed-tech; mostly pilot-scale, vendor-dependent | High adoption in rural & urban SMEs for CRM, analytics, supply chain, finance | Expanding but limited beyond urban centres; pilot & sector-specific | Tourism, retail, manufacturing; moderate, urban-focused |

| Infrastructure & Digital Readiness | Limited electricity, high connectivity cost, uneven infrastructure | Stronger digital infrastructure, affordable cloud services, AIaaS; urban-rural divide persists | Weak internet, frequent power outages, limited cloud/AI base | Better urban base; rural areas lag; economic instability |

| Skills & Human Capital | Shortage of AI/data-driven skills; limited training and organizational readiness | Growing AI talent pool; urban SMEs more skilled; rural SMEs still lag | Major skills gap outside cities; shortage of AI expertise | Moderate digital literacy in cities; limited rural adoption |

| Key Barriers | Pilot-scale projects, vendor-dependency, uneven state support | Digital divide, inequitable access; rural SMEs lag; adoption skewed to urban areas | Policy uncertainties, infrastructure, high implementation cost, skills shortage | Ethical concerns, AI model interpretability, economic instability |

| Pillars | Description | Global References | Key Enablers |

|---|---|---|---|

| T—Target | Identify SME constraints and opportunities for AI adoption, including financial bottlenecks and risk exposures | Singapore’s SME AI roadmaps and sector-specific pilots | Needs assessment, policy-guided sector analysis, risk assessment |

| R— Restructure | Redesign value propositions and workflows with AI augmentation to improve financial efficiency and governance capacity | Estonia’s e-governance APIs and SME digital workflows | AI toolkits, cloud platforms, digital workflows |

| I— Integrate | Embed AI into business processes (CRM, analytics, automation, financial forecasting) | China’s widespread integration of AI in e-commerce SMEs | APIs, AIaaS, low-code platforms |

| A— Accelerate | Scale market reach, personalise services, optimise logistics, and enhance cash-flow resilience | China’s AI-powered fintech and retail ecosystems | ML models, NLP, recommender systems |

| D—Democratise | Ensure inclusive ethical access, bridging rural–urban divides and strengthening SME access to finance | Estonia’s digital ID inclusivity, Singapore’s SkillsFuture | Open-source AI, SME training, micro-financing, compliance guidance |

| Dimension | Before (Traditional SME Practices) | After (With TRIAD-AI Framework) |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Focus | Limited awareness of AI potential; short-term cost orientation. | Target pillar identifies AI-driven opportunities and aligns them with long-term business goals. |

| Organisational Structure | Fragmented processes; manual workflows; low cross-functional coordination. | Restructure pillar redesigns value creation and workflows with AI-enabled efficiency and governance. |

| Technology Integration | Sporadic tool adoption; little interoperability or scaling. | Integrate pillar embeds AI across functions to support automation, analytics, and predictive decision-making. |

| Growth and Market Reach | Constrained by local operations and limited scalability. | Accelerate pillar leverages digital ecosystems and data-driven models to expand markets and optimise growth. |

| Ethics and Inclusivity | Uneven access, weak compliance, and limited awareness of AI ethics. | Democratise pillar ensures equitable access, ethical use, and inclusive capacity-building. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahman, M.M. AI-Driven Business Model Innovation and TRIAD-AI in South Asian SMEs: Comparative Insights and Implications. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 709. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120709

Rahman MM. AI-Driven Business Model Innovation and TRIAD-AI in South Asian SMEs: Comparative Insights and Implications. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(12):709. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120709

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahman, Md Mizanur. 2025. "AI-Driven Business Model Innovation and TRIAD-AI in South Asian SMEs: Comparative Insights and Implications" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 12: 709. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120709

APA StyleRahman, M. M. (2025). AI-Driven Business Model Innovation and TRIAD-AI in South Asian SMEs: Comparative Insights and Implications. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(12), 709. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120709