1. Introduction

Over the past ten years, the banking industry has undergone a fundamental transformation due to the quick development of financial technology, or fintech. Digital innovations, from blockchain and artificial intelligence to automated risk management systems and mobile banking platforms, have been progressively adopted by European banks. Banks have been able to improve their information processing skills and create more complex methods of risk assessment thanks to these technological developments (

Ding et al., 2022;

Tang et al., 2023). In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the banking industry has also experienced substantial regulatory changes. In order to increase the resilience of the banking sector, the Basel III framework imposed strict liquidity requirements. The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) are two crucial liquidity metrics that were created to ensure banks maintain adequate liquid assets and reliable funding sources (

Distinguin et al., 2013). Understanding how these elements interact for financial stability is more important than ever as European banks deal with regulatory tightening and technological advancement.

Even though fintech is becoming increasingly important in banking operations, and liquidity management has become crucial since Basel III, the literature currently in publication provides inconsistent evidence regarding their relationship. Few studies specifically investigate how digital transformation impacts regulatory liquidity compliance in European markets, even though many studies analyse the impact of fintech on bank performance and innovation (

Mirza et al., 2023). Comparably, the majority of Basel III liquidity ratio research concentrates on how these ratios directly affect bank lending and stability (

Al-Harbi, 2017), paying little attention to technological mediating factors. This research gap is particularly pronounced regarding the moderating role of ESG performance and the mediating mechanisms through which fintech influences default risk via liquidity channels. So, it raises the main research question: Does higher fintech increase liquidity risk management in European listed banks? To what extent does ESG performance moderate the association between fintech and liquidity management? Does liquidity mediate the relationship between fintech and firm value? Thus, it is worth investigating the relationship between fintech and liquidity management in the context of contemporary European banking

We employ a sample of 45 European banks listed in the STOXX 600 index from 2019 to 2024 to investigate these research questions. Using ordinary least squares regressions with year and country fixed effects, we construct a fintech index based on the frequency of ten technology-related keywords in banks’ annual reports, following the methodology of

Kharrat et al. (

2024). Our main findings reveal that fintech adoption significantly increases liquidity management capabilities of European banks, as measured by both LCR and NSFR. However, our result shows that ESG performance weakens the positive relationship between fintech and Basel III liquidity ratios, suggesting potential resource allocation conflicts between sustainability initiatives and technological investments. Furthermore, our mediation analysis shows that LCR partially mediates the fintech-default risk relationship, indicating a complex trade-off where fintech-driven liquidity improvements may come at the cost of increased default risk, possibly due to liquidity-profitability trade-offs or regulatory compliance costs. To address potential endogeneity concerns, we perform several robustness tests, including alternative proxies for liquidity, lagged independent variables, propensity score matching and subsample analysis based on bank size.

This study makes several important contributions to the literature. First, we provide novel empirical evidence on the relationship between fintech adoption and Basel III liquidity compliance in European banking, addressing a significant gap in existing research. Second, we advance understanding of how ESG performance moderates the fintech-liquidity nexus, offering insights into the complex interplay between sustainability practices and technological innovation in banking. Third, our mediation analysis reveals the indirect pathways through which fintech influences default risk via liquidity channels, contributing to the broader literature on fintech and financial stability. Fourth, methodologically, we develop a comprehensive framework for measuring fintech adoption using textual analysis of annual reports, which can be applied in future banking research. Finally, our findings have important policy implications for European banking regulators seeking to balance fintech innovation, liquidity requirements, and financial stability objectives.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. We begin by providing a comprehensive review of the relevant literature on fintech, liquidity management, and hypothesis development in

Section 2. Subsequently,

Section 3 describes our research methodology, including data sources, variable construction, and econometric specifications.

Section 4 presents the main empirical results, covering baseline regressions, moderation analysis, and mediation tests. We then report robustness checks and additional analyses in

Section 5 to ensure the reliability of our findings. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines potential directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Fintech

Financial technology (fintech) has undergone substantial transformation during the last ten years through technological solutions that enhance and automate financial service delivery. According to the Financial Stability Board definition, fintech describes technological innovations in financial services that create new business models and applications, processes, and products that affect financial markets and institutions substantially (

Wen et al., 2023). Fintech applications in banking operations cover digital payments, together with blockchain technology, artificial intelligence, big data analytics, and automated risk management systems.

Empirical research shows that financial technology adoption creates significant changes in banking operations and performance results.

Tang et al. (

2023) show that fintech development improves corporate competitiveness through three key mechanisms, which include reduced financing constraints, increased research and development spending, and broader market penetration. The market conditions become more bearish when state-owned enterprises and traditional industries experience the strongest effects from fintech development.

Ding et al. (

2022) demonstrate that fintech development enables corporate innovation through its ability to ease financial constraints and boost research and development investments. The mechanism behind this effect works through better bank lending and intensified loan market competition, which arises from internet credit increasing funding supply and affecting traditional banking operations through spillover effects.

Research on fintech adoption in banking employs various methods to assess adoption rates, but textual analysis of corporate disclosures remains the essential measurement technique. Multiple markets validate this approach because fintech indices created from corporate disclosures effectively measure banking institutions’ digital transformation levels according to (

Dicuonzo et al., 2024). The research indicates that higher fintech adoption rates in European and US banks lead to better ESG performance, which demonstrates how technological progress drives sustainable banking operations.

Fintech adoption produces effects on multiple bank operational areas while simultaneously affecting risk management practices.

Wu et al. (

2024) investigated how fintech adoption impacts bank liquidity creation through their study of the top 300 US banks, while discovering a recurring negative relationship between fintech adoption and bank liquidity creation. The authors explain that fintech banks enhance their screening and monitoring abilities, which results in more discerning lending behaviour that reduces liquidity production.

Mirza et al. (

2023) present opposite findings regarding European banks, which show fintech investments create positive effects on green lending, together with risk-adjusted returns on capital. The connection between fintech and bank performance shows different patterns based on the specific market and regulatory settings.

Financial reporting quality enhancement through fintech represents an essential aspect of how technology affects banking institutions. Chinese listed firms experience reduced real earnings management according to

Wen et al. (

2023) because of regional fintech development, which leads to improved information production and external monitoring and better credit accessibility. The adoption of fintech appears to improve corporate governance systems while decreasing information disparities, which in turn enhances the transparency and reliability of financial institutions.

Previous literature shows that fintech adoption produces substantial effects on banking operations through its ability to boost competitiveness and innovation while affecting risk management practices. However, the evidence on specific performance outcomes remains mixed, with effects varying across different markets and regulatory contexts. This highlights the importance of examining fintech’s impact within specific institutional frameworks, particularly in the European banking environment.

2.2. Liquidity Management

Liquidity management has become an essential aspect of banking operations, especially after the 2008 financial crisis, which revealed the susceptibility of financial institutions to liquidity disruptions.

Al-Homaidi et al. (

2019) say that bank liquidity is basically the ability of a bank to fund asset growth and meet both expected and unexpected cash and collateral obligations at a reasonable cost without taking on unacceptable losses. This management includes funding liquidity, which is about how easy it is for banks to obtain loans, and market liquidity, which is about how easy it is to turn assets into cash without losing much value.

The Basel III regulatory framework added two important liquidity metrics to help banks deal with liquidity risks better. The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) says banks must have enough high-quality liquid assets to last through a 30-day stress test. The Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) says that banks should use stable funding sources over a one-year period (

Distinguin et al., 2013). These requirements mark a significant transformation in regulatory strategy, transitioning from conventional capital-centric metrics to directly tackling liquidity risk management.

Banks have had to make significant changes to their asset-liability management strategies and buy advanced systems to monitor liquidity because of these standards. Empirical research on the determinants of bank liquidity uncovers a multifaceted array of factors that affect liquidity positions.

Al-Harbi (

2017) delineates essential bank-specific determinants, including capital adequacy, bank size, asset quality, and profitability, in conjunction with macroeconomic factors such as monetary policy and inflation rates. The connection between these factors and liquidity differs significantly in different banking systems and regulatory settings. For instance,

Munteanu (

2012) finds that the factors that affect liquidity before a crisis are very different from those that affect it during a crisis. For example, measures of bank stability become very important during times of financial stress. The correlation between liquidity management and bank performance has garnered significant academic scrutiny, indicating non-linear relationships.

Vu (

2024) illustrates an inverted U-shaped correlation between LCR and profitability in Vietnamese banks, indicating that initial increases in liquidity coverage improve performance. However, holding too much liquidity beyond the optimal level leads to lower returns because of the costs of missing out on other opportunities.

Sidhu et al. (

2022) also look at Indian banks and find that while LCR compliance lowers liquidity risk, it does so at the cost of lower net interest margins and higher non-performing assets. This result shows the trade-offs that come with managing liquidity. Recent studies have examined the interplay between liquidity requirements and other regulatory measures.

Polizzi et al. (

2020) examine the correlation between capital and liquidity requirements, discovering that both factors positively influence lending growth and bank stability, albeit via distinct mechanisms. Their analysis shows that the rules work differently depending on how well they protect creditor rights and how strict they are about non-traditional banking activities. The outcome indicates that liquidity management’s influence transcends individual banks’ performance, affecting wider systemic stability factors.

The previous literature argues that good liquidity management means balancing several conflicting goals, such as following the rules, making the most money, and lowering risk. Basel III’s liquidity requirements have made the banking sector more resilient, but they have also made operations more complicated and created potential performance trade-offs that banks must carefully manage. To figure out how new technologies, like fintech adoption, might affect how banks manage their money, it is important to understand these dynamics.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

Building on the literature reviewed above, this section develops our main hypotheses regarding the relationships between fintech adoption, ESG performance, liquidity management, and default risk in European banking.

2.3.1. Fintech and Liquidity Management

The theoretical foundation for the relationship between fintech adoption and liquidity management rests on information asymmetry theory and operational efficiency arguments. Fintech innovations fundamentally enhance banks’ information processing capabilities, enabling more accurate cash flow forecasting, real-time liquidity monitoring, and automated collateral management (

Ding et al., 2022). These technological improvements should theoretically strengthen banks’ ability to maintain optimal liquidity levels and comply with Basel III requirements more efficiently.

From an operational perspective, fintech adoption can improve liquidity management through several channels. Digital technologies enable banks to predict customer behaviour and cash flow patterns better, reducing uncertainty in liquidity planning. Automated systems can optimise the composition of high-quality liquid assets required for LCR compliance, whilst blockchain and AI technologies can enhance the efficiency of collateral management and funding market participation (

Tang et al., 2023). Moreover, fintech platforms can facilitate access to diverse funding sources and improve the speed of liquidity adjustments during stress scenarios.

Empirical evidence supports this theoretical reasoning.

Wu et al. (

2024) find that fintech adoption influences banks’ liquidity creation. However, their focus on US banks and liquidity creation differs from our emphasis on European banks and regulatory liquidity ratios. The enhanced screening and monitoring capabilities associated with fintech should enable banks to maintain more efficient liquidity buffers whilst meeting regulatory requirements. Therefore, we hypothesise:

Hypothesis 1. Fintech positively affects banks’ liquidity management.

2.3.2. ESG Performance as a Moderator

The moderating role of ESG performance in the fintech-liquidity relationship stems from competing resource allocation demands and stakeholder considerations. Banks with strong ESG commitments face competing demands for financial and managerial resources between sustainability initiatives and technological investments (

Mirza et al., 2023). ESG-focused banks may prioritise investments in green finance infrastructure, sustainable lending platforms, and environmental risk management systems over pure efficiency-driven fintech applications.

Additionally, ESG-oriented banks may adopt a more conservative approach to liquidity management, prioritising stability and long-term sustainability over short-term efficiency gains. This conservative stance could reduce the effectiveness of fintech tools in optimising liquidity positions, as ESG considerations may override purely algorithmic recommendations for liquidity allocation. The literature on ESG and fintech interaction suggests that whilst both can enhance bank performance individually, their combined effect may involve trade-offs due to competing strategic priorities (

Dicuonzo et al., 2024).

Furthermore, stakeholder theory suggests that banks with high ESG performance face greater scrutiny from diverse stakeholder groups, potentially constraining their ability to fully exploit fintech-driven liquidity optimisation strategies that might appear to prioritise efficiency over stability. The regulatory complexity associated with both ESG compliance and fintech implementation may also create operational friction that dampens the positive effect of technology on liquidity management. Therefore, we hypothesise:

Hypothesis 2. ESG performance moderates the relationship between fintech and banks’ liquidity management, with higher ESG levels weakening the positive fintech-liquidity relationship.

2.3.3. Liquidity Management as an Intermediary

The mediating role of liquidity management in the relationship between fintech adoption and bank default risk presents a complex theoretical framework involving both risk mitigation and potential risk amplification mechanisms. On one hand, improved liquidity management through fintech adoption should theoretically reduce default risk by enhancing banks’ ability to meet short-term obligations and weather financial stress (

Vu, 2024). Enhanced liquidity monitoring and forecasting capabilities enable banks to maintain adequate buffers and respond more effectively to unexpected cash outflows, thereby reducing the probability of distress.

However, the relationship may involve more nuanced mechanisms that could paradoxically increase default risk despite liquidity improvements. Drawing on recent theoretical and empirical insights, we identify three key channels through which this counterintuitive effect may operate.

First, the regulatory compliance costs and profitability trade-offs associated with maintaining higher liquidity buffers may undermine long-term solvency. Whilst Basel III liquidity requirements enhance short-term resilience, they impose opportunity costs through reduced lending capacity and lower-yielding liquid asset holdings (

Sidhu et al., 2022). Research on European banks demonstrates that compliance with liquidity regulations, whilst improving stability measures, can compress net interest margins and reduce profitability (

Soenen & Vander Vennet, 2022). In their comprehensive study of European banks’ default risk determinants,

Soenen and Vander Vennet (

2022) find that traditional profitability measures (ROA, ROE) are negatively associated with default risk, whilst regulatory capital ratios show positive associations under certain specifications. This suggests that the profitability erosion from excessive liquidity holdings could elevate default risk over longer horizons by weakening capital accumulation capacity.

Second, fintech-enhanced liquidity management may induce moral hazard effects whereby banks perceive reduced liquidity risk and consequently increase risk-taking in other dimensions. The improved real-time monitoring and automated liquidity management capabilities provided by fintech could create a false sense of security, leading banks to expand into riskier lending segments or leverage positions more aggressively.

Durango-Gutiérrez et al. (

2023), examining microfinance institutions under Basel III, document that whilst liquidity coverage ratios improve institutional resilience to short-term shocks, they do not eliminate default risk stemming from credit quality deterioration or operational vulnerabilities. Their findings suggest that liquidity improvements may be offset by risk compensation behaviour in other areas.

Third, the resource allocation implications of fintech investment itself may create vulnerabilities. As discussed in our moderation hypothesis, substantial capital and managerial resources devoted to fintech implementation may constrain banks’ flexibility in other risk management areas. The fixed costs of technological infrastructure, cybersecurity investments, and continuous system upgrades represent ongoing commitments that could reduce banks’ ability to absorb unexpected losses or adapt to changing market conditions. Moreover, technological complexity and operational dependencies on digital systems introduce new categories of operational and cyber risks that may not be fully reflected in traditional default risk measures (

Soenen & Vander Vennet, 2022).

The mediation mechanism may also reflect the differential impact of liquidity improvements across the business cycle. During normal economic conditions, fintech-enhanced liquidity management may primarily serve to optimize operational efficiency and regulatory compliance, with limited implications for fundamental credit risk. However, during stress periods when liquidity and solvency risks become intertwined, the benefits of improved liquidity management may be overshadowed by deteriorating asset quality or systemic contagion effects that fintech cannot fully mitigate.

Empirically, the mediation relationship can be decomposed into direct and indirect effects. The indirect effect through liquidity management (fintech → liquidity → default risk) may be negative, reflecting genuine risk reduction through improved liquidity resilience. However, if the direct effect (fintech → default risk, controlling for liquidity) remains negative or becomes more negative, this indicates that fintech influences default risk through additional channels beyond liquidity management. These channels may include the profitability compression, risk compensation behaviour, and resource allocation trade-offs discussed above.

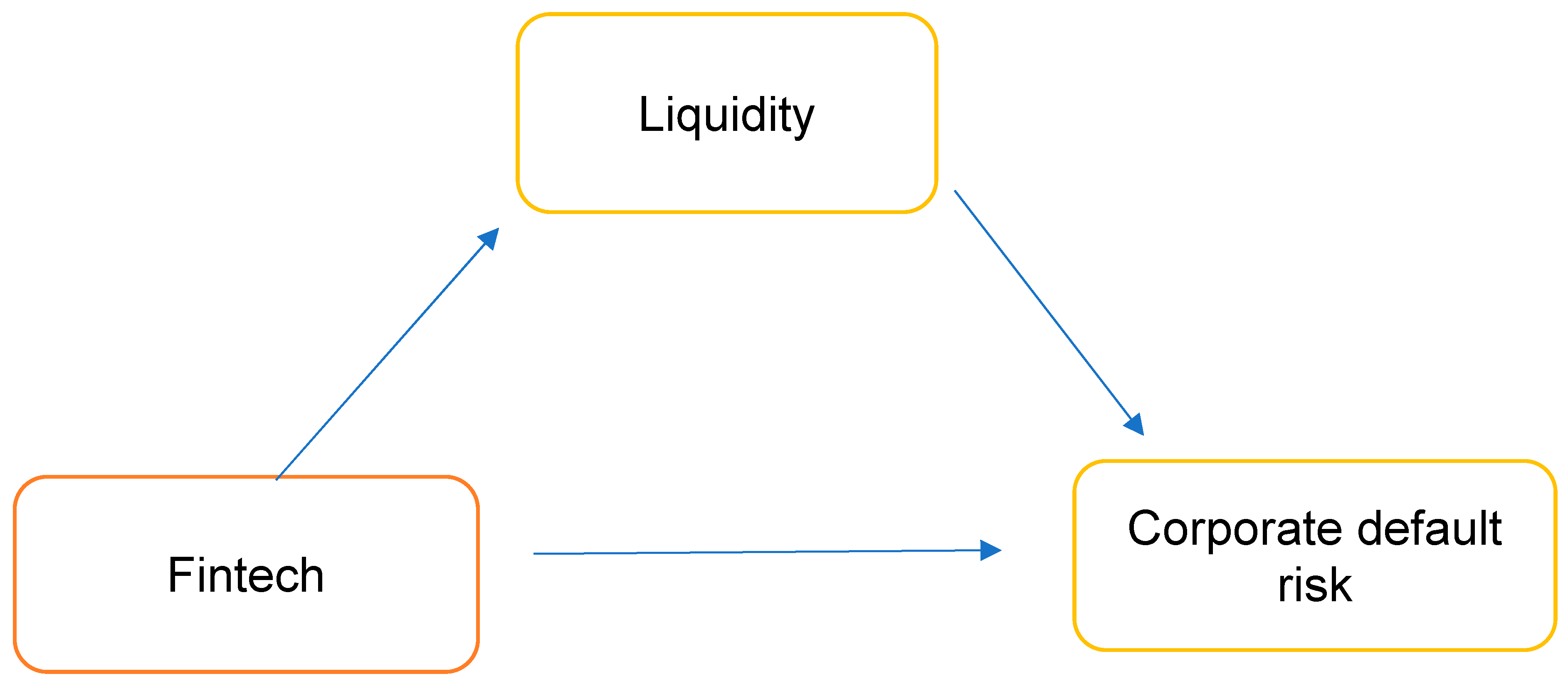

Figure 1 illustrates our conceptual framework for these hypothesised relationships. Therefore, we hypothesise:

Hypothesis 3. Liquidity management serves as a mediator in the relationship between fintech adoption and bank default risk, suggesting a potential trade-off between immediate liquidity enhancements and enduring default risk.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data Sample

Our sample consists of 45 publicly listed banks drawn from the STOXX 600 index, representing major European financial institutions across 12 countries, including the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Belgium, Austria, and Norway, over the period 2019 to 2024. We focus on European markets for several reasons. First, European banks have been at the forefront of implementing Basel III liquidity requirements, providing an ideal setting to examine the interaction between regulatory compliance and technological innovation. Second, Europe represents a diverse regulatory and institutional environment across multiple jurisdictions, enabling us to capture substantial variation in both fintech adoption and liquidity management practices whilst controlling for country-level heterogeneity. This timeframe was selected to capture the recent acceleration in fintech adoption and artificial intelligence integration within the European banking sector, particularly following the increased digitalisation trends observed during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Financial and accounting data were collected from Bloomberg and DataStream, providing standardised metrics across all institutions in our sample. To construct our fintech adoption measure, we manually collected annual reports from each bank’s official website for textual analysis purposes. This approach ensures consistency in data collection and allows for accurate measurement of fintech-related disclosures across different reporting formats and languages.

Following standard practice in banking research, all continuous variables were winsorised at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the influence of extreme outliers that could distort our empirical results. This procedure helps ensure that our findings are robust and not driven by a small number of exceptional observations. The final dataset comprises 251 bank-year observations, providing sufficient variation for our empirical analysis whilst maintaining focus on the most relevant and comparable European banking institutions.

3.2. Independent Variables

Our main independent variables measure bank liquidity management through the two essential Basel III liquidity ratios. We use the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) to measure liquidity management according to Basel Committee on Banking Supervision guidelines (

Distinguin et al., 2013).

According to Basel III regulations, the LCR measures high-quality liquid assets against total net cash outflows during a 30-day stress period. Banks use this metric to demonstrate their ability to survive short-term liquidity crises through maintaining sufficient easily convertible asset buffers. The regulatory minimum requirement for LCR stands at 100% while higher values indicate superior short-term liquidity resilience. The NSFR measures the relationship between available stable funding and required stable funding throughout a one-year period. The measure evaluates bank structural liquidity through an assessment of funding stability against asset liquidity characteristics. The NSFR helps banks manage longer-term liquidity risks by promoting the use of stable funding sources, including customer deposits and long-term debt (

Vu, 2024).

The ratios are collected directly from banks’ regulatory disclosures and annual reports, which follow standardised Basel III definitions. We transform percentage-reported LCR and NSFR values into decimal format to achieve consistency in our statistical evaluation. The two measures offer different insights about liquidity management since LCR shows short-term stability and NSFR demonstrates funding stability over time.

3.3. Dependent Variable

We measure fintech adoption using a textual analysis approach based on the frequency of technology-related keywords in banks’ annual reports. Following the methodology established by

Kharrat et al. (

2024), we construct a fintech index by identifying the occurrence of ten key fintech-related terms (listed in

Table 1):

Technology, Digital Banking, Network, Internet Banking, Online Services, FinTech, AI, Blockchain, E-payment, and Mobile Banking.The construction of our fintech index follows several systematic steps. First, we download annual reports in PDF format from each bank’s official website for all years in our sample period. These reports are then converted to text format using automated conversion tools to enable systematic keyword searching. We employ R programming language version 4.4.1 for textual analysis, utilising appropriate text mining packages to calculate the frequency of each fintech-related keyword within each annual report.

To ensure accuracy and consistency, we clean the data by removing instances where keywords appear in negative contexts, such as phrases containing “no” or “none” that might indicate the absence of certain technologies. Following

Dicuonzo et al. (

2024), the fintech index for each bank-year observation is calculated as the sum of frequencies across all ten keywords. Our main fintech variable is then constructed as the natural logarithm of this sum to address potential skewness in the distribution and facilitate interpretation of results.

This approach captures banks’ disclosure intensity regarding fintech adoption and provides a comprehensive measure of their engagement with digital technologies. Higher values of the fintech index indicate greater emphasis on technology-related initiatives and innovations in banks’ strategic communications, reflecting their commitment to digital transformation efforts (

Wen et al., 2023).

3.4. Control Variables

To ensure the robustness of our empirical results and control for alternative explanations, we include several control variables identified in prior literature as important determinants of liquidity management and bank performance.

3.4.1. Governance Controls

We include three governance-related variables to capture the influence of board characteristics on bank liquidity decisions. The percentage of independent directors (Ind) reflects board independence, which may influence risk management and liquidity strategies through enhanced oversight (

Dicuonzo et al., 2024). Board size (Boardsize) is measured as the total number of directors on the board, capturing potential effects of board structure on decision-making efficiency. Gender diversity is controlled through the percentage of women on the board (P_Fe), as diverse boards may adopt different approaches to risk and liquidity management.

3.4.2. Financial Controls

We incorporate key financial characteristics that may influence liquidity management decisions. Financial leverage (Lev) captures banks’ overall risk profile and regulatory constraints that may affect liquidity strategies. The price-to-book ratio (Pb) reflects market valuation and growth opportunities, which may influence banks’ liquidity allocation decisions. Bank size (Size) is measured as the natural logarithm of total assets, controlling for potential scale effects in liquidity management and differential regulatory treatment for larger institutions (

Al-Homaidi et al., 2020).

These control variables help isolate the specific effects of fintech adoption and ESG performance on liquidity management by accounting for fundamental bank characteristics that may confound our main relationships of interest. All control variables are included simultaneously in our regression models to ensure comprehensive control for alternative explanations.

3.5. Model Specification

Our study examines how fintech adoption influences liquidity management in European banks through multiple analytical approaches. We begin with ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models, accounting for time and country effects through year and country fixed effects. Following

Petersen (

2009), we employ two-way clustering of standard errors at both firm and year levels to ensure robust statistical inference and address potential cross-sectional and time-series dependence in the residuals. Prior to estimation, we conducted diagnostic tests, including variance inflation factor analysis (

Appendix A Table A1), and Breusch-Pagan tests for heteroskedasticity (

Appendix A Table A2), to validate our modelling assumptions and justify the use of robust standard errors. Our baseline model specification examines the direct relationship between fintech adoption and liquidity management:

where Liquid_{i,t} represents our liquidity measures (LCR or NSFR) for bank i in year t, and Fin_{i,t} captures fintech adoption intensity. The model includes comprehensive control variables (Controls_{i,t}), year fixed effects (D_{year}), and country fixed effects (D_{country}) to control for time-invariant country characteristics and common time trends.

3.5.1. Moderation Analysis

To test whether ESG performance moderates the relationship between fintech adoption and liquidity management, we extend Equation (1) by introducing an interaction term between fintech and ESG:

The coefficient β_3 captures the moderating effect of ESG performance on the fintech-liquidity relationship. A significant β_3 indicates that the impact of fintech on liquidity management varies depending on banks’ ESG performance levels.

3.5.2. Mediation Analysis

Furthermore, we explore the mediating role of liquidity in the relationship between fintech and corporate default risk. Drawing from well-established methodological approaches in the literature (

Baron & Kenny, 1986), we specify two additional equations to examine this mediation mechanism:

where corporate default risk is proxied by Distance to Default (DTD), Fin represents fintech adoption, and Liquid captures liquidity management performance. The control variables are as defined in our main specifications.

Our mediation analysis decomposes the relationship between fintech and firm corporate default risk into direct and indirect effects. In this framework, β_4 in Equation (3) captures the total effect of fintech on default risk, while β_7in Equation (4) represents the direct effect after controlling for liquidity. The indirect effect through liquidity is calculated as the product β_1 × β_8, where β_1 comes from Equation (1) and β_8 represents the coefficient on liquidity in Equation (4). Since these components sum to the total effect, we can test our mediation hypothesis by estimating Equations (1) and (4). Consistent with our third hypothesis, we expect the mediation analysis to reveal complex trade-offs where fintech-driven liquidity improvements may influence default risk through multiple channels.

This mediation framework allows us to understand the mechanisms through which fintech adoption affects bank stability, providing insights into whether liquidity management serves as a channel for risk transmission or mitigation in the context of digital transformation in European banking.

Table 1.

Definition of variables.

Table 1.

Definition of variables.

Main

Dependent Variables | Description |

|---|

| LCR | Liquidity Coverage Ratio: The ratio of high-quality liquid assets to total net cash outflows over a 30-day stress period, as defined by Basel III regulations |

| NSFR | Net Stable Funding Ratio: The ratio of available stable funding to required stable funding over a one-year horizon, measuring structural liquidity position |

| Dependent variable: Default risk | |

| DTD | Distance To Default: A market-based measure of default probability derived from Merton’s structural model, where higher values indicate lower default risk |

| Independent Variable | |

| Fintech | Our task is to measure the frequency related to the occurrence of keywords in the annual reports of banks in the sample. We adopted the same 10 keywords applied in the study by Kharrat et al. (2024): Technology, Digital Banking, Network, Internet Banking, Online Services, FinTech, AI, Blockchain, E-payment and Mobile Banking. |

| ESG | ESG performance score obtained from the Bloomberg database. |

| Control Variables | |

| Ind | Percentage of independent directors on the board of directors |

| Boardsize | Total number of directors serving on the board of directors |

| P_Fe | The percentage of female directors on the board of directors |

| Lev | Financial leverage ratio calculated as total debt divided by total equity |

| Pb | Price-to-book ratio measured as market valuation relative to book value |

| Size | Bank size is measured as the natural logarithm of total assets |

4. Empirical Result

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for our sample of 43 European banks from 2019 to 2024. The fintech adoption variable shows considerable variation across banks, with a mean value of 4.014 and a standard deviation of 1.104, indicating substantial heterogeneity in digital transformation efforts within our sample. The range extends from 0 to 5.749, suggesting that some banks have minimal fintech-related disclosures, whilst others demonstrate extensive technological engagement.

The liquidity management variables reveal interesting patterns in regulatory compliance. The LCR exhibits a mean of 1.824 (182.4%), well above the regulatory minimum of 100%, with moderate variation (standard deviation of 0.642), ranging from 127.3% to 382.4%. This suggests that most European banks in our sample maintain substantial liquidity buffers beyond regulatory requirements, although there is some dispersion in their short-term liquidity management strategies. The NSFR demonstrates relatively less variation, with a mean of 1.339 (133.9%) and standard deviation of 0.350, indicating more consistent structural funding practices across institutions.

Governance characteristics show that European banks maintain relatively independent boards, with an average of 71.24% independent directors. Board sizes average 13.068 members, whilst gender diversity varies considerably, with women comprising between 16.67% and 63.64% of board positions (mean 39.53%). Financial performance indicators reveal positive average returns (ROA of 0.743%), though with notable variation, whilst leverage ratios and price-to-book ratios demonstrate the diverse risk profiles within our sample.

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix for our key variables. Importantly, the correlations between independent variables remain below 0.8, indicating no severe multicollinearity concerns. The correlation between fintech adoption and our liquidity measures is positive but modest (0.032 for LCR and 0.151 for NSFR), providing initial support for our hypotheses. We also estimate the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for the empirical models (see

Appendix A Table A1). The results show that the VIF for any independent variable does not exceed the critical value of 3.0; hence, we conclude there is no multicollinearity in our data. This confirms that our regression models can reliably isolate the individual effects of each explanatory variable on liquidity management.

4.2. Baseline Result

Table 4 presents the baseline regression results examining the relationship between fintech adoption and liquidity management in European banks. The results provide strong support for our first hypothesis, demonstrating that fintech adoption significantly enhances both short-term and structural liquidity management capabilities. The coefficient in fintech adoption is positive and highly significant for both liquidity measures. Specifically, a one-unit increase in log fintech adoption is associated with a 0.321 increase in LCR (

p < 0.01) and a 0.048 increase in NSFR (

p < 0.05). In economic terms, a one standard deviation increase in fintech adoption (1.104) corresponds to approximately a 35.4 percentage point improvement in LCR and a 5.3 percentage point enhancement in NSFR, representing substantial effects relative to sample means of 182.4% and 133.9%, respectively.

The control variables largely behave as expected and provide additional insights into liquidity management determinants. Board independence (Ind) shows a positive and significant relationship with both liquidity measures, suggesting that more independent governance structures promote conservative liquidity policies. Conversely, board size (Boardsize) exhibits a negative coefficient for LCR, potentially reflecting coordination challenges in larger boards that may impede effective liquidity oversight.

Gender diversity (P_Fe) demonstrates a positive relationship with LCR, consistent with the literature suggesting that diverse boards adopt more conservative risk management approaches. Profitability (ROA) shows a positive association with LCR but a negative association with NSFR, indicating potential trade-offs between short-term liquidity buffers and longer-term funding efficiency. Bank size (Size) exhibits negative coefficients for both measures, supporting the “too-big-to-fail” hypothesis that larger institutions maintain lower liquidity ratios due to perceived implicit government support.

These baseline results provide strong empirical support for Hypothesis 1, which predicted that fintech positively affects banks’ liquidity management. The positive and statistically significant coefficients for fintech adoption across both LCR and NSFR specifications confirm that digital transformation enhances European banks’ ability to maintain adequate liquidity buffers and comply with Basel III requirements. Both models demonstrate strong explanatory power, with R2 values of 54.7% for LCR and 74.7% for NSFR, establishing a robust foundation for our subsequent moderation and mediation analyses.

4.3. Moderation Analysis

Table 5 presents the results of our moderation analysis, examining whether ESG performance moderates the relationship between fintech adoption and liquidity management. The findings provide compelling support for our second hypothesis, revealing that ESG performance significantly weakens the positive relationship between fintech and liquidity management across both measures. The interaction term between fintech and ESG (Fintech:ESG) is negative and statistically significant for both LCR (−0.131,

p < 0.1) and NSFR (−0.042,

p < 0.01), indicating that the beneficial effects of fintech on liquidity management diminish as banks’ ESG performance increases.

The main effects reveal interesting patterns that complement the interaction results. Fintech adoption shows an even stronger positive coefficient when ESG is included as a moderator (0.880 for LCR and 0.226 for NSFR), suggesting that fintech’s impact on liquidity is most pronounced for banks with lower ESG scores. ESG performance itself demonstrates a positive direct effect on NSFR (0.229, p < 0.01) but shows no significant direct relationship with LCR, indicating that sustainable practices may influence structural funding decisions more than short-term liquidity management. The negative interaction effects suggest that banks with higher ESG commitments face resource allocation conflicts between sustainability initiatives and fintech-driven liquidity optimisation, consistent with our theoretical predictions about competing strategic priorities.

To better understand the economic significance of these moderation effects, we can examine the conditional effects at different ESG levels. For banks with low ESG scores (one standard deviation below the mean), the effect of fintech on LCR remains strongly positive. However, for banks with high ESG scores (one standard deviation above the mean), the fintech effect is substantially diminished, supporting our argument that ESG-focused banks may prioritise sustainability investments over pure efficiency-driven technological applications. The control variables maintain their expected signs and significance levels, with the models showing improved explanatory power (R2 of 55.7% for LCR and 79.4% for NSFR) compared to the baseline specifications. These results provide strong empirical support for Hypothesis 2, confirming that ESG performance moderates the fintech-liquidity relationship, with higher ESG levels weakening the positive effects of digital transformation on liquidity management capabilities.

4.4. Mediation Analysis

Table 6 presents the results of our mediation analysis examining whether liquidity management mediates the relationship between fintech adoption and bank default risk. Following the established mediation framework, we estimate three key equations to decompose the total effect of fintech on default risk into direct and indirect components. The results reveal a complex mediation mechanism that provides partial support for our third hypothesis, demonstrating that liquidity management serves as a significant mediating channel whilst highlighting important trade-offs in the fintech-default risk relationship.

Column (1) establishes the total effect of fintech on default risk, showing a negative and significant coefficient (−0.180, p < 0.05), indicating that higher fintech adoption is associated with increased default risk. This counterintuitive finding suggests that whilst fintech may improve operational efficiency, it may also introduce new risks or encourage more aggressive risk-taking behaviour. Column (2) confirms our baseline finding that fintech positively affects liquidity management (0.321, p < 0.01), establishing the first pathway in the mediation chain. Column (3) presents the full mediation model, where both fintech and LCR are included as predictors of default risk. The direct effect of fintech becomes somewhat smaller in magnitude (−0.147, p < 0.1), whilst LCR shows a negative and significant relationship with default risk (−0.105, p < 0.05).

The mediation results reveal that liquidity management partially mediates the fintech-default risk relationship, but in a manner that highlights complex trade-offs rather than simple risk mitigation. The indirect effect through LCR can be calculated as the product of the fintech-LCR coefficient (0.321) and the LCR-default risk coefficient (−0.105), yielding an indirect effect of approximately −0.034. This suggests that fintech adoption reduces default risk through improved liquidity management by about 0.034 units. However, this beneficial indirect effect is more than offset by the direct effect (−0.147), resulting in a net positive relationship between fintech and default risk. These findings support Hypothesis 3, confirming that liquidity management mediates the fintech-default risk relationship. However, the mediation reveals a trade-off, where fintech-driven liquidity improvements may come at the cost of increased default risk through other channels.

The control variables provide additional insights into the default risk determinants. Board independence shows a consistent negative relationship with default risk across specifications, whilst board size exhibits a positive association, suggesting governance trade-offs in risk management. The price-to-book ratio demonstrates a strong positive relationship with default risk, potentially reflecting market perceptions of underlying risk factors. These mediation results highlight the nuanced nature of fintech’s impact on bank stability, where technological improvements in liquidity management may simultaneously introduce new sources of risk that require careful management and regulatory oversight.

5. Robustness Test

5.1. Endogeineity

A key concern in our analysis is the potential endogeneity arising from reverse causality, omitted variables, or simultaneity bias. To address these concerns comprehensively, we employ three distinct approaches: lagged independent variables, firm fixed effects, and propensity score matching. These multiple strategies provide robust evidence that our main findings are not driven by endogeneity issues.

Table 7 presents results using one-year lagged explanatory variables to mitigate reverse causality concerns. By ensuring that fintech adoption measures temporally precede liquidity outcomes, we reduce the possibility that liquidity management decisions influence fintech adoption rather than vice versa. The lagged fintech variable (Fintech_lag1) maintains its positive and statistically significant relationship with both liquidity measures, with coefficients of 0.388 (

p < 0.01) for LCR and 0.091 (

p < 0.01) for NSFR. These magnitudes are comparable to or stronger than our baseline results, suggesting that the positive effects of fintech on liquidity management persist and potentially strengthen over time as digital integration matures. The consistency of control variable patterns and model fit (R

2 of 54.8% for LCR and 79.2% for NSFR) provides confidence that temporal ordering does not drive our main findings.

Whilst the lagged approach addresses reverse causality, concerns about time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity across banks remain.

Table 8 presents results incorporating firm fixed effects in addition to our baseline fixed effects, controlling for all time-invariant bank-specific characteristics that might simultaneously influence both fintech adoption and liquidity management. Such characteristics include organisational culture, historical business models, or management quality that are difficult to measure directly. The fintech coefficients remain positive and significant for both LCR (0.096,

p < 0.05) and NSFR (0.033,

p < 0.1), though with somewhat smaller magnitudes compared to baseline results. The attenuation is expected when exploiting within-bank variation over time rather than cross-sectional differences, as firm fixed effects absorb substantial variation in the data. Nevertheless, the continued significance of fintech effects demonstrates that changes in digital transformation within individual banks over time genuinely drive improvements in liquidity management, rather than merely reflecting cross-sectional differences in bank characteristics.

Beyond controlling for observable and unobservable time-invariant factors, we further address potential selection bias through propensity score matching.

Table 9 presents results using full matching methodology, which creates a balanced comparison between high-fintech and low-fintech banks based on observable characteristics. We classify banks as high-fintech if their fintech adoption exceeds the sample median and construct matched samples ensuring comparable distributions of control variables between treatment and control groups. The results show that high-fintech banks maintain significantly higher liquidity ratios, with coefficients of 0.090 (

p < 0.1) for LCR and 0.095 (

p < 0.01) for NSFR. The consistency of these effects with our baseline findings, combined with well-balanced covariate distributions in the matched sample, confirms that observed differences in liquidity management genuinely reflect fintech adoption rather than pre-existing differences between high-tech and low-tech banks.

Collectively, these three complementary approaches to addressing endogeneity provide strong evidence that our main findings are robust to various potential sources of bias. The persistence of positive and significant fintech effects across all specifications, despite different identifying assumptions and estimation strategies, substantially strengthens confidence in the causal interpretation of our results.

5.2. Alternative Proxy for Liquidity Management

To further validate our findings, we employ an alternative measure of liquidity management using the loan-to-deposit ratio (LTD) as our dependent variable. This traditional liquidity metric captures banks’ fundamental intermediation function and provides a different perspective on liquidity management compared to the regulatory Basel III ratios.

Table 10 presents the results using LTD as the dependent variable across three specifications: baseline effect (column 1), moderation analysis (column 2), and lagged approach (column 3).

The results using the alternative liquidity proxy reveal interesting patterns that complement our main findings. In the baseline specification (column 1), fintech adoption shows a negative and significant relationship with LTD (−0.098, p < 0.01), indicating that higher fintech adoption is associated with lower loan-to-deposit ratios. This finding is consistent with our main results when properly interpreted, as lower LTD ratios typically indicate more conservative liquidity management and higher liquidity buffers, which aligns with the positive effects we observed for LCR and NSFR.

The moderation analysis (column 2) provides additional support for our second hypothesis regarding ESG’s moderating role. The main effect of fintech becomes more negative (-0.236, p < 0.01), while ESG shows a negative direct effect (−0.202, p < 0.05) on LTD. Importantly, the interaction term (Log_Fintech:ESG) is positive and significant (0.033, p < 0.1), indicating that ESG performance weakens the negative relationship between fintech and LTD. This is consistent with our main findings, as it suggests that ESG-focused banks are less likely to fully exploit fintech capabilities for conservative liquidity management, supporting our resource allocation conflict hypothesis.

The lagged specification (column 3) confirms the robustness of these relationships over time, with the lagged fintech variable maintaining its negative and significant effect (−0.130, p < 0.01). The control variables generally behave consistently across specifications, with board size showing consistent negative effects and price-to-book ratio demonstrating negative relationships with LTD, which is logical given that higher market valuations may be associated with more conservative liquidity strategies. These results using an alternative liquidity measure provide strong additional support for our main conclusions, demonstrating that the positive effects of fintech on liquidity management are robust across different conceptual approaches to measuring bank liquidity.

5.3. Size Context

To investigate whether bank size influences the relationship between fintech adoption and liquidity management, we split our main sample into two subgroups based on the median bank size. This analysis allows us to examine potential heterogeneity in the fintech-liquidity relationship across different bank categories, as larger and smaller banks may face distinct operational constraints, regulatory environments, and technological adoption challenges.

Table 11 presents the results for large banks (above median size) and small banks (below median size) across both LCR and NSFR specifications.

The results reveal striking heterogeneity in the fintech-liquidity relationship based on bank size. For large banks, fintech adoption shows a negative and significant relationship with LCR (−0.094, p < 0.05) but no significant effect on NSFR (0.004, p > 0.1). This suggests that larger institutions may face different trade-offs when implementing fintech solutions, potentially reflecting their more complex operational structures and diverse business models that may constrain the liquidity benefits of technological adoption. The negative effect on LCR for large banks could indicate that these institutions use fintech capabilities to optimise their short-term liquidity positions more aggressively, operating closer to regulatory minimums.

In contrast, small banks demonstrate strongly positive relationships between fintech adoption and both liquidity measures. The coefficient for LCR is particularly large and significant (1.347, p < 0.01), whilst the NSFR coefficient is also positive and significant (0.176, p < 0.01). These substantial effects suggest that smaller banks derive greater liquidity management benefits from fintech adoption, potentially due to their simpler operational structures that allow for more straightforward implementation of digital solutions, or because they face greater resource constraints that make efficiency gains from technology more valuable.

The control variables show interesting patterns across size categories. For large banks, most governance variables show limited significance, whilst leverage demonstrates a marginally negative effect on LCR. For small banks, several control variables maintain their expected relationships, with board independence positively affecting NSFR and price-to-book ratio showing strong positive associations with both liquidity measures. The model fit varies considerably, with small banks showing particularly high explanatory power for NSFR (R2 = 83.5%), suggesting that the determinants of liquidity management are more predictable for smaller institutions. These size-based differences highlight the importance of considering institutional heterogeneity when evaluating the impacts of fintech adoption on banking operations and suggest that regulatory and managerial approaches to fintech implementation may need to account for bank size characteristics.

6. Conclusions

This research investigates how European banking institutions use fintech to control their liquidity management while analysing how digital transformation affects Basel III liquidity requirements and financial system stability. This study analyses 43 European banks in the STOXX 600 index from 2019 to 2024 through a comprehensive dataset to present original empirical findings about technological innovation effects on ESG performance and liquidity management capabilities. The research results strongly verify our three fundamental research hypotheses. Our research shows that adoption of financial technology leads to improved liquidity management at banks through positive statistical effects on Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR). The implementation of digital technology enables financial institutions to enhance their liquidity management through advanced information processing and real-time monitoring, along with automated risk management systems. The positive link between fintech adoption and liquidity management weakens when banks have higher ESG performance levels, according to our moderation analysis. Banks that dedicate resources to ESG goals experience conflicts in allocating resources between ESG initiatives and liquidity optimisation through fintech platforms. The research reveals how different performance targets within banking institutions affect each other, which demonstrates potential trade-offs between objectives.

Our results remain robust across multiple specifications, including lagged independent variables, firm fixed effects, propensity score matching, and alternative liquidity measures. Notably, our size-based analysis reveals significant heterogeneity, with small banks deriving substantially greater liquidity benefits from fintech adoption compared to large banks.

These findings have important implications for banking practice, regulation, and academic research. For bank managers, our results suggest that fintech investments can meaningfully enhance liquidity management capabilities, though the benefits vary significantly by bank size. Small banks should prioritise fintech adoption given their substantially greater liquidity benefits, whilst large banks should focus on integrating technology with existing complex systems. Banks with strong ESG commitments need to carefully balance resource allocation between sustainability initiatives and technological investments, potentially seeking synergies through green fintech solutions.

For regulators, our findings highlight several concrete policy considerations. Supervisory frameworks should incorporate assessment of banks’ IT risk management capabilities alongside traditional liquidity monitoring, as fintech adoption fundamentally alters liquidity risk profiles. We recommend that regulators develop fintech-specific scenarios for liquidity stress testing that account for technology failures, cyber risks, or rapid shifts in digital banking behaviour during crises. Liquidity regulations may benefit from size-adjusted implementation guidance, recognising that smaller institutions derive greater benefits from fintech adoption. Additionally, regulators should establish clear disclosure guidelines for fintech investments in prudential reporting, enabling more effective monitoring of the technology-liquidity nexus. Our mediation results, revealing increased default risk through non-liquidity channels, suggest that supervisors should adopt holistic oversight approaches considering how fintech simultaneously affects multiple risk dimensions.

The study contributes to the growing literature on fintech in banking by providing the first comprehensive analysis of how digital transformation affects Basel III liquidity compliance in European markets. Our methodology for measuring fintech adoption through textual analysis offers a replicable approach for future research, whilst our moderation and mediation frameworks provide insights into complex mechanisms through which technology influences banking outcomes. Future research could extend this analysis to other regulatory frameworks, explore specific technological components driving observed effects, or examine how the fintech-liquidity relationship evolves as regulatory requirements and technological capabilities continue to develop.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.N.L.N. and P.T.D.; Methodology, M.N.L.N.; Data analysis, M.N.L.N.; Software, M.N.L.N.; Formal analysis, M.N.L.N.; Data curation, M.N.L.N.; Original draft, M.N.L.N.; Visualisation. M.N.L.N.; Validation, P.T.D.; Review & Editing, P.T.D.; Supervision, P.T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the reported results can be obtained from commercial databases (Bloomberg and Refinitiv/LSEG) subject to licensing agreements, and from publicly available bank annual reports accessible through institutional investor relations websites.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that helped improve this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

VIF.

| | Model LCR | Model NSFR |

|---|

| Fintech | 2.97114 | 2.626847 |

| Ind | 4.636198 | 4.912913 |

| Boardsize | 4.966826 | 5.322174 |

| P_Fe | 2.030356 | 2.081808 |

| ROA | 5.567091 | 5.520482 |

| Lev | 3.519312 | 3.992448 |

| Pb | 2.446836 | 2.395842 |

| Size | 7.035928 | 7.837751 |

Table A2.

Breusch-Pagan Test for Heteroskedasticity.

Table A2.

Breusch-Pagan Test for Heteroskedasticity.

| Model | Test Statistic | p-Value | Result |

|---|

| LCR | 56.432 | 0.0011 | Heteroskedasticity detected |

| NSFR | 36.588 | 0.1282 | No heteroskedasticity |

References

- Al-Harbi, A. (2017). Determinants of banks liquidity: Evidence from OIC countries. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 33(2), 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Homaidi, E. A., Tabash, M. I., Al-Ahdal, W. M., Farhan, N. H. S., & Khan, S. H. (2020). The liquidity of Indian firms: Empirical evidence of 2154 firms. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(1), 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Homaidi, E. A., Tabash, M. I., Farhan, N. H., & Almaqtari, F. A. (2019). The determinants of liquidity of Indian listed commercial banks: A panel data approach. Cogent Economics & Finance, 7(1), 1616521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicuonzo, G., Palmaccio, M., & Shini, M. (2024). ESG, governance variables and Fintech: An empirical analysis. Research in International Business and Finance, 69, 102205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N., Gu, L., & Peng, Y. (2022). Fintech, financial constraints and innovation: Evidence from China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 73, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distinguin, I., Roulet, C., & Tarazi, A. (2013). Bank regulatory capital and liquidity: Evidence from US and European publicly traded banks. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(9), 3295–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durango-Gutiérrez, M. P., Lara-Rubio, J., & Navarro-Galera, A. (2023). Analysis of default risk in microfinance institutions under the Basel III framework. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 28(2), 1261–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrat, H., Trichilli, Y., & Abbes, B. (2024). Relationship between FinTech index and bank’s performance: A comparative study between Islamic and conventional banks in the MENA region. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 15(1), 172–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, N., Umar, M., Afzal, A., & Firdousi, S. F. (2023). The role of fintech in promoting green finance, and profitability: Evidence from the banking sector in the euro zone. Economic Analysis and Policy, 78, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, I. (2012). Bank liquidity and its determinants in Romania. Procedia Economics and Finance, 3, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M. A. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 435–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, S., Scannella, E., & Suárez, N. (2020). The role of capital and liquidity in bank lending: Are banks safer? Global Policy, 11(S1), 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, A. V., Rastogi, S., Gupte, R., & Bhimavarapu, V. M. (2022). Impact of liquidity coverage ratio on performance of select Indian banks. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(5), 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenen, N., & Vander Vennet, R. (2022). Determinants of European banks’ default risk. Finance Research Letters, 47, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S., Chen, Z., Chen, J., Quan, L., & Guan, K. (2023). Does FinTech promote corporate competitiveness? Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters, 58, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T. H. (2024). Liquidity coverage ratio and profitability: An inverted U-shaped pattern. Cogent Economics & Finance, 12(1), 2426532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H., Fang, J., & Gao, H. (2023). How FinTech improves financial reporting quality? Evidence from earnings management. Economic Modelling, 126, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., Pathan, S., & Zheng, C. (2024). FinTech adoption in banks and their liquidity creation. The British Accounting Review, 101322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).