Portfolio Diversification with Non-Conventional Assets: A Comparative Analysis of Bitcoin, FinTech, and Green Bonds Across Global Markets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

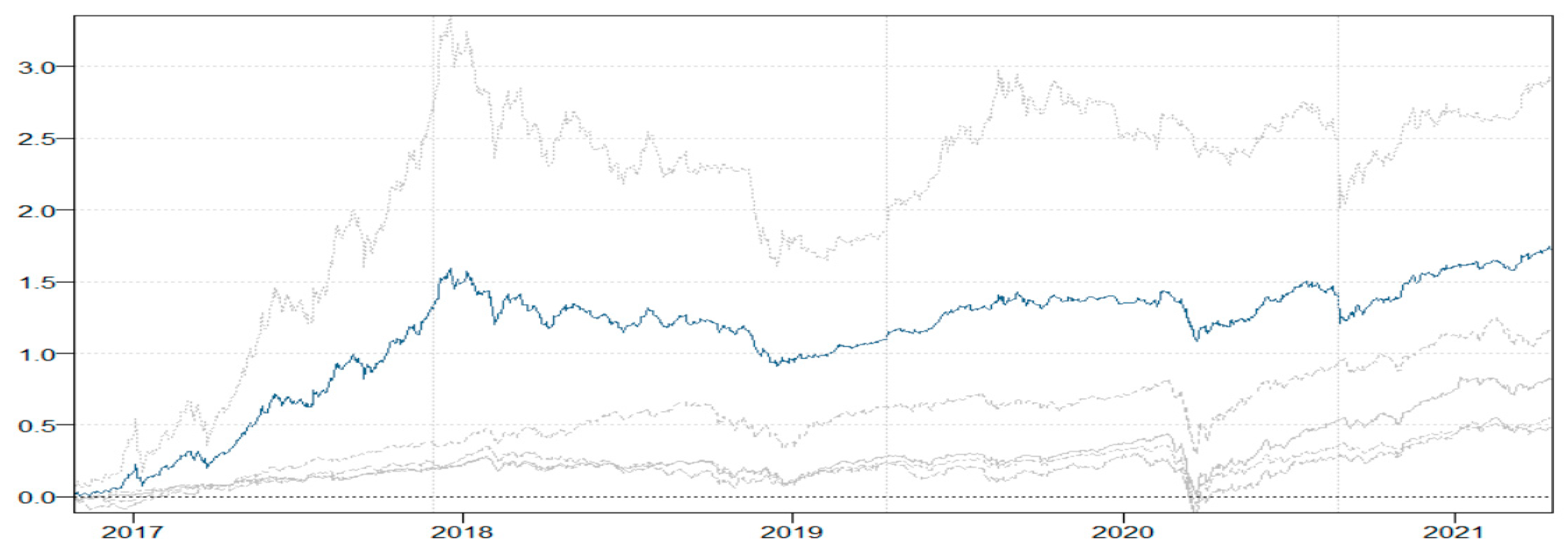

2.1. Cryptocurrencies and Diversification

2.2. FinTech Equities and Financial Market Dynamics

2.3. Green Bonds and Sustainable Investment Linkages

2.4. Research Gap

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Methodological Roadmap

- (1)

- Data Collection: We start by gathering raw financial data from various sources. This foundational step ensures that we have accurate and relevant information to work with.

- (2)

- Model Estimation (TVP-VAR): Next, we apply a Time-Varying Parameter Vector Autoregression (TVP-VAR) model. This sophisticated statistical technique helps us estimate the dynamic relationships and connections between different financial assets over time, allowing us to see how they interact with one another.

- (3)

- Network Construction: After estimating the model, we construct a network that visually represents these interconnections. This network helps us understand the complex relationships among the assets, highlighting how they influence each other.

- (4)

- Portfolio Optimization (MCP): Finally, we leverage the insights gained from the previous steps to optimize our investment portfolios using the Minimum Connectedness Portfolio (MCP) approach. This step focuses on minimizing systemic risk, ensuring that our portfolios are not only well-diversified but also resilient to market shocks.

3.1.1. Data Profile

- (1)

- Bitcoin (BTC) acts as a stand-in for the digital asset market, showcasing innovations in decentralized finance. It is a key player that reflects how digital currencies are reshaping the financial landscape.

- (2)

- FINX, on the other hand, represents the performance of companies within the FinTech ecosystem. This includes firms involved in digital payments, blockchain applications, and various online financial services. Essentially, it gives us a glimpse into how these tech-driven companies are performing in the market.

- (3)

- QGREEN tracks businesses that are committed to the green economy and renewable technologies. It embodies the shift towards sustainability, focusing on equities that are driving the transition to a more environmentally friendly future.

3.1.2. Time-Varying Parameter Vector Autoregression (TVP-VAR)

3.1.3. Network Analysis

3.1.4. Portfolio Techniques: Minimum Connectedness Portfolio (MCoP)

3.1.5. Robustness Analysis

4. Empirical Findings

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

4.2. Average Connectedness Measures

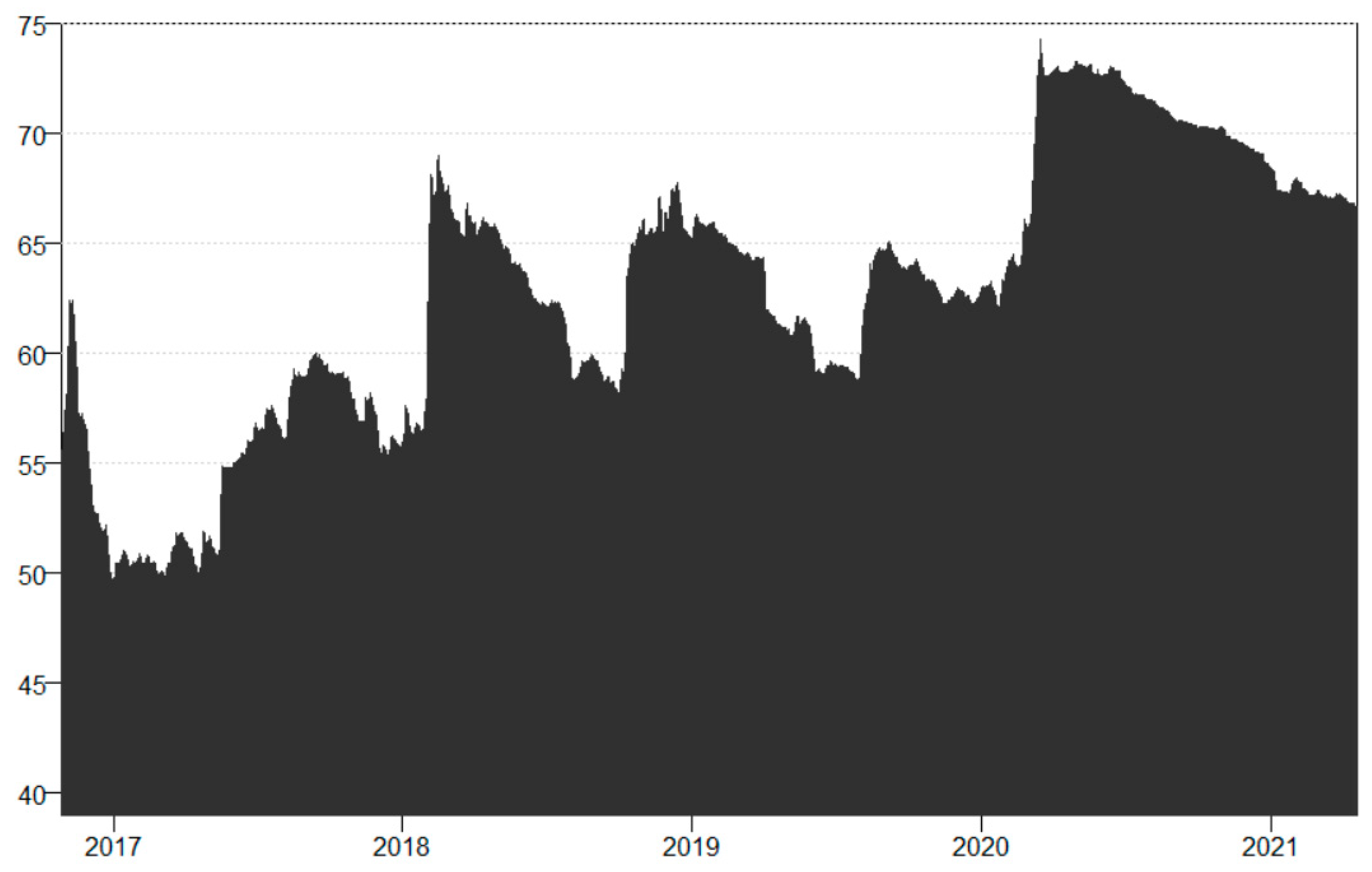

4.3. Dynamic Total Connectedness

4.4. Net Total Directional Connectedness

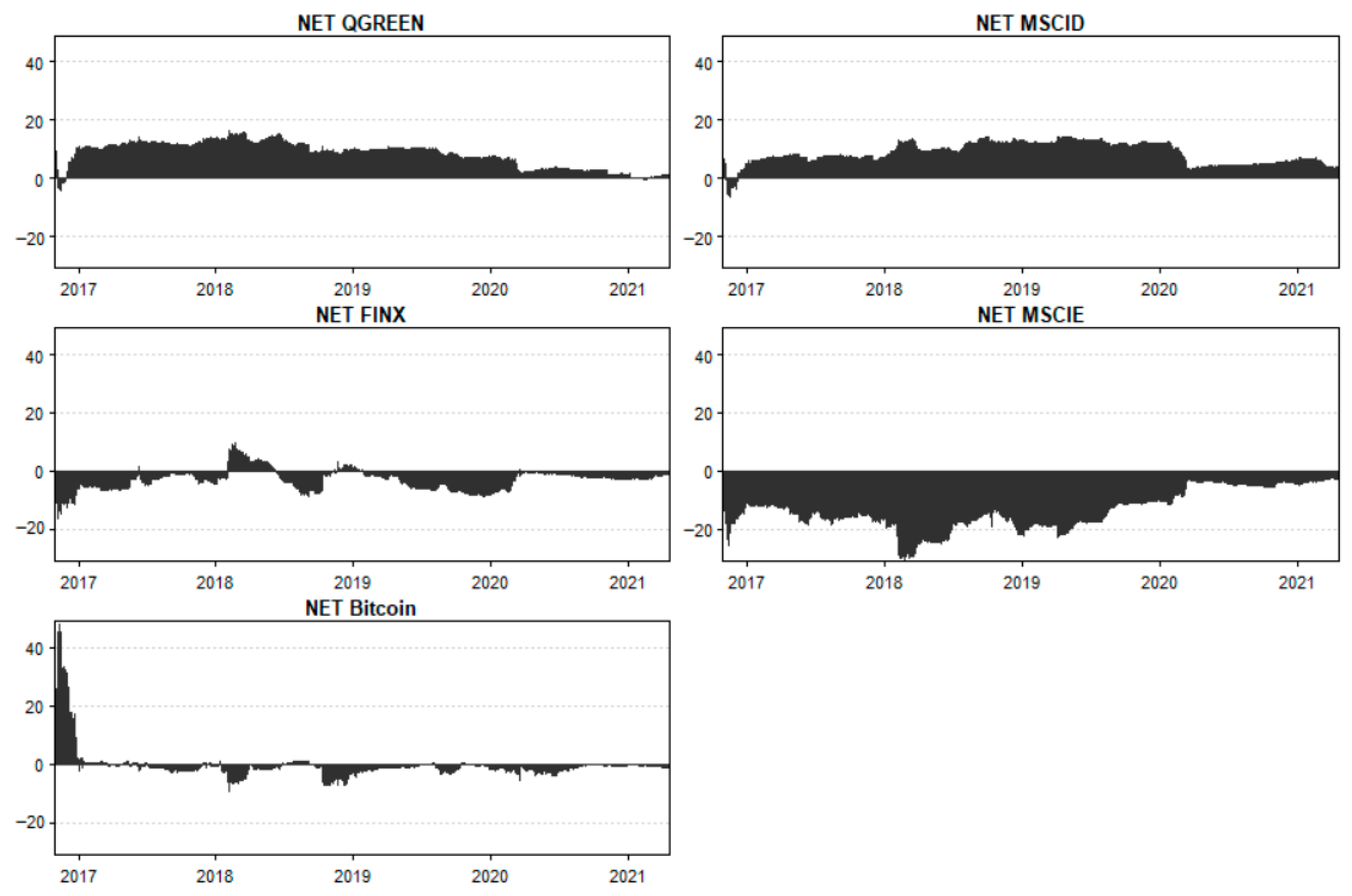

4.5. Net Pairwise Connectedness

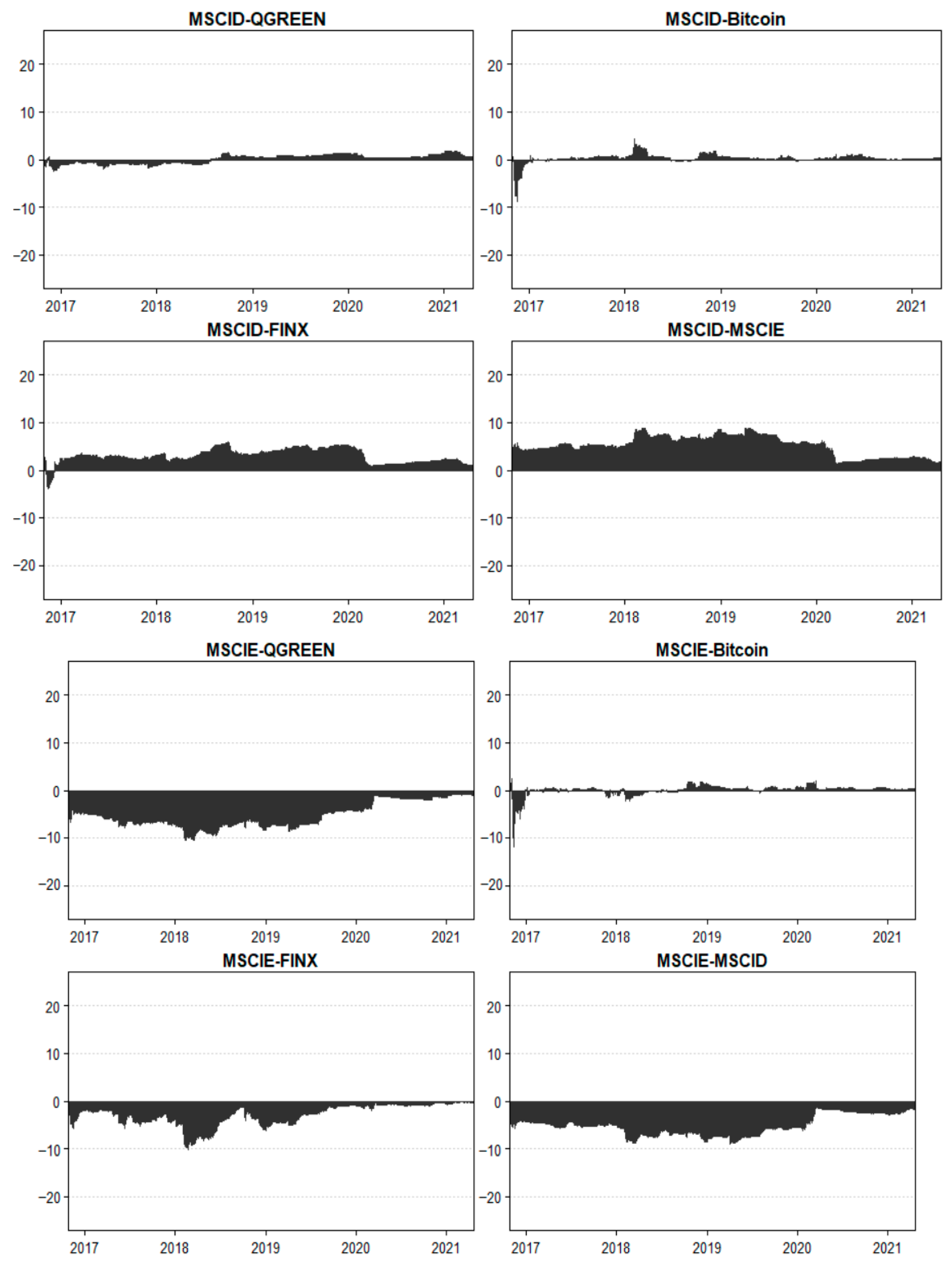

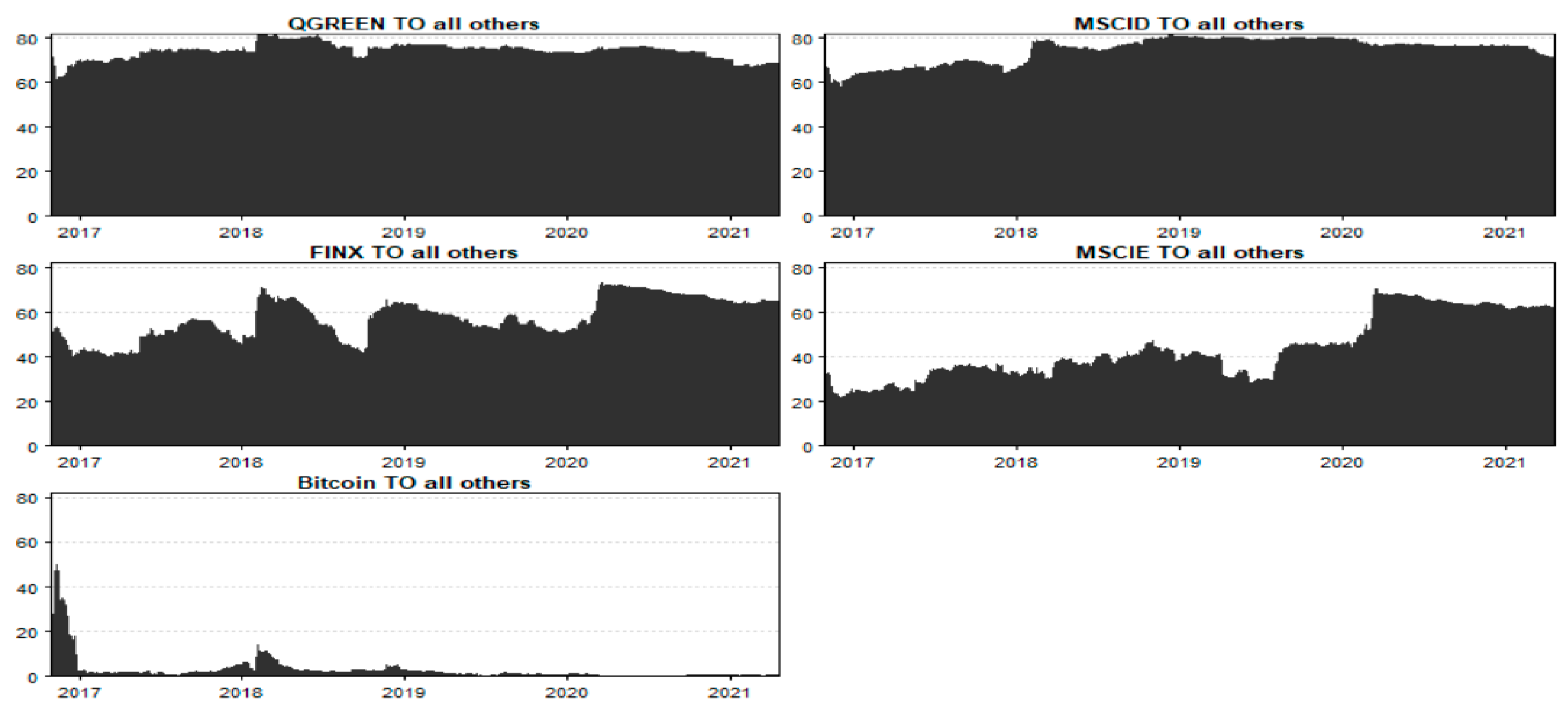

4.6. Dynamic Transmissions of Spillovers

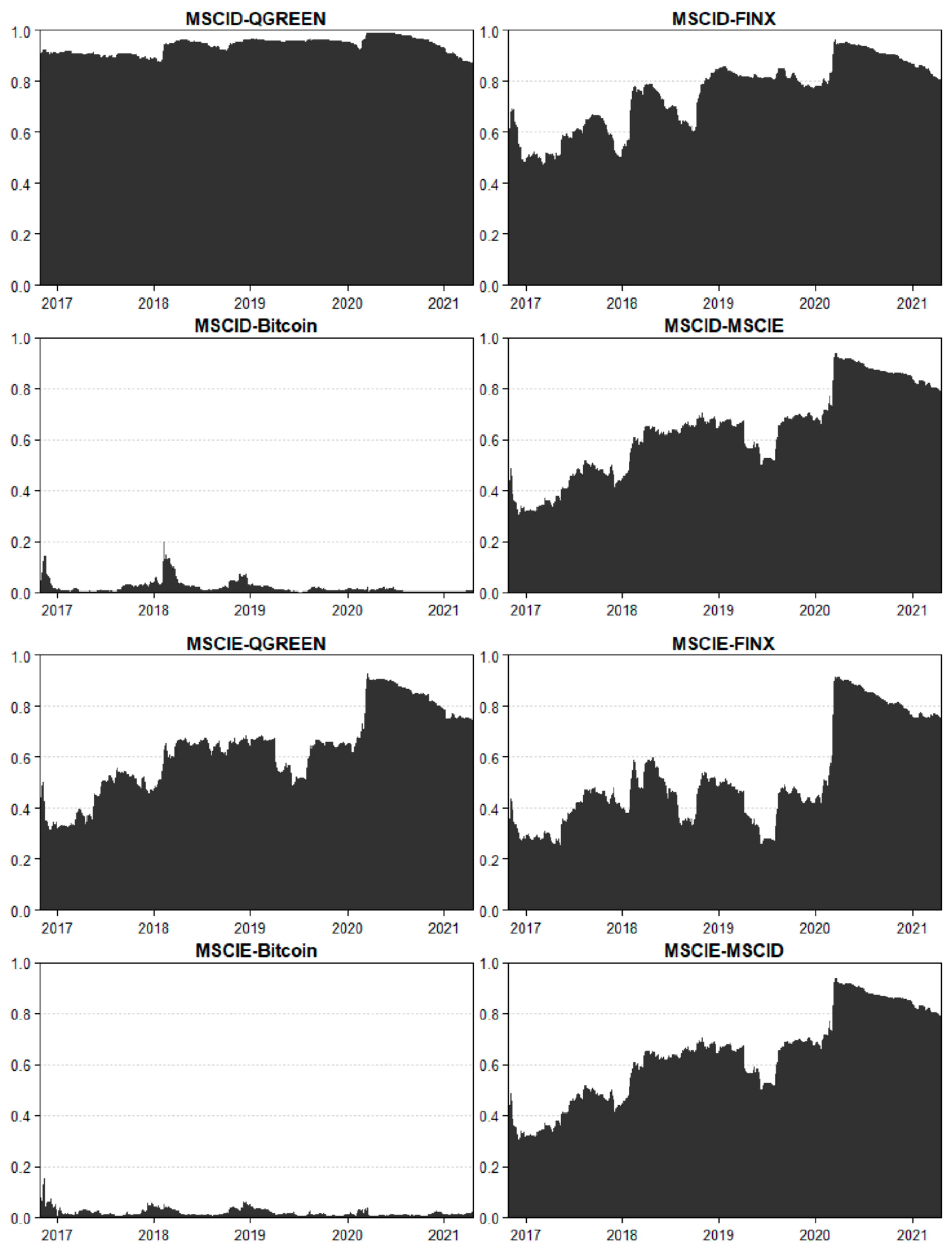

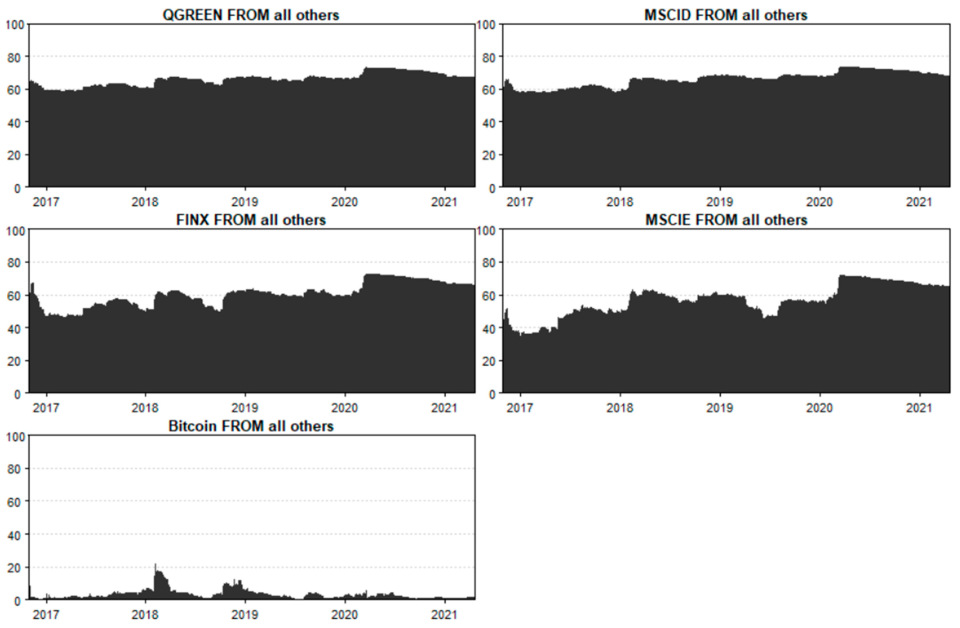

4.7. Evidence of Network Analysis

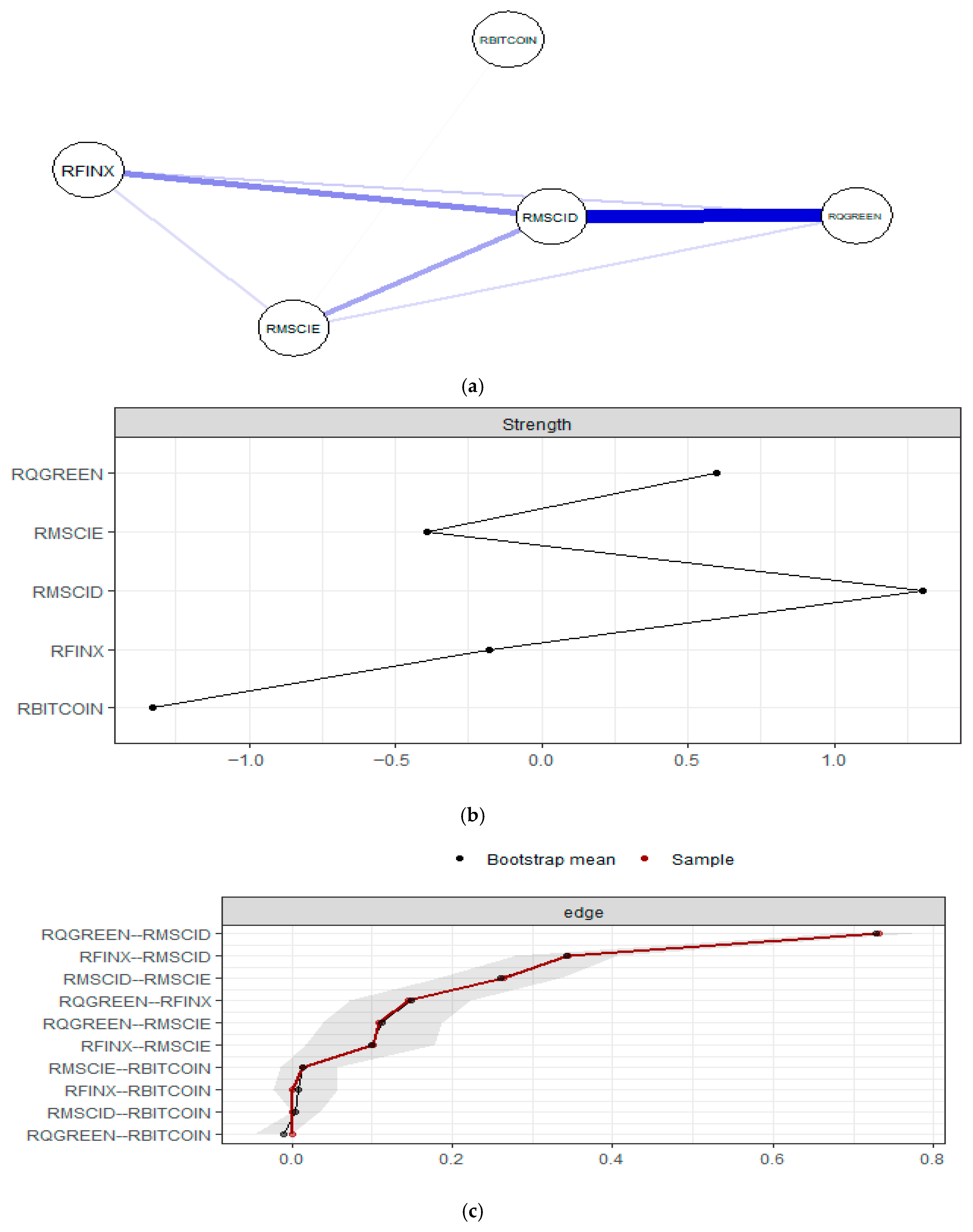

4.8. Portfolio Implications

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abakah, E. J. A., Tiwari, A. K., Ghosh, S., & Doğan, B. (2023). Dynamic effect of Bitcoin, fintech and arti-ficial intelligence stocks on eco-friendly assets, Islamic stocks and conventional financial markets: Another look using quantile-based approaches. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 192, 122566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M., Sofia, R., Josyula, H. P., Pandey, B. K., Kumar, S., & Sarkar, U. A. (2024, November 15–16). AI-driven risk management in financial markets and fintech. 2024 Second International Conference Computational and Characterization Techniques in Engineering & Sciences (IC3TES) (pp. 1–5), Lucknow, India. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M. M., & Rahman, M. M. (2019). Regulatory challenges and opportunities in the FinTech landscape: A review. International Journal of Financial Studies, 7(4), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, S. S., Naveed, M., Ali, S., & Moussa, F. (2025). Sailing towards sustainability: Connectedness between ESG stocks and green cryptocurrencies. International Review of Economics & Finance, 98, 103848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. (2022). Combatting against COVID-19 & misinformation: A systematic review. Human Arenas, 5(2), 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ante, L., & Kauffman, R. J. (2023). The role of stablecoins and NFTs in modern portfolio diversifi-cation. Journal of Digital Finance, 5(2), 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakakis, N., Chatziantoniou, I., & Gabauer, D. (2019). Cryptocurrency market contagion: Market uncertainty, market complexity, and dynamic portfolios. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 61, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, N., Chatziantoniou, I., & Gabauer, D. (2020). Refined measures of dynamic connectedness based on time-varying parameter vector autoregressions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(4), 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, N., & Gabauer, D. (2017). Refined measures of dynamic connectedness based on TVP-VAR (Mpra Paper 78282). University Library of Munich.

- Apergis, N., & Apergis, E. (2022). The role of COVID-19 for Chinese stock returns: Evidence from a GARCHX model. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics, 29(5), 1175–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, M., Naeem, M. A., Farid, S., Nepal, R., & Jamasb, T. (2022). Diversifier or more? Hedge and safe haven properties of green bonds during COVID-19. Energy Policy, 168, 113102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, U. S., Tariq, A., Farrukh, M., Raza, A., & Iqbal, M. K. (2022). Green bonds for sustainable development: Review of literature on development and impact of green bonds. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S. P. (2005). Centrality and network flow. Social Networks, 27(1), 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouri, E., Gupta, R., Tiwari, A. K., & Roubaud, D. (2017). Does Bitcoin hedge global uncertainty? Evidence from wavelet-based quantile-in-quantile regressions. Finance Research Letters, 23, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Broadstock, D. C., Chatziantoniou, I., & Gabauer, D. (2022). Minimum connectedness portfolios and the market for green bonds: Advocating socially responsible investment (SRI) activity. In Applications in energy finance: The energy sector, economic activity, financial markets and the environment. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Celik, I., Demir, S., Hol, A. O., & Celik, M. (2025). Asymmetric interconnectedness and investing strategies of green, sustainable and environmental markets. Investment Analysts Journal, 1–27, ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C. L., McAleer, M., & Tansuchat, R. (2011). Crude oil hedging strategies using dynamic multivariate GARCH. Energy Economics, 33(5), 912–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemkha, R., BenSaïda, A., Ghorbel, A., & Tayachi, T. (2021). Hedge and safe haven properties during COVID-19: Evidence from Bitcoin and gold. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 82, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Zheng, Z., Ma, M., Wu, J., Zhou, Y., & Yao, J. (2020). Dependence structure between bitcoin price and its influence factors. International Journal of Computational Science and Engineering, 21(3), 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, M., Mehta, C., Lal, P., & Srivastava, A. (2024). Does the big boss of coins—Bitcoin—Protect a portfolio of new-generation cryptos? Evidence from memecoins, stablecoins, NFTs and DeFi. China Finance Review International, 14(3), 480–521. [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen, P., Errunza, V., Jacobs, K., & Jin, X. (2014). Correlation dynamics and international diversification benefits. International Journal of Forecasting, 30(3), 807–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, T., Corbet, S., & McGee, R. J. (2020). Are cryptocurrencies a safe haven for equity markets? An international perspective from the COVID-19 pandemic. Research in International Business and Finance, 54, 101248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diebold, F. X., & Yılmaz, K. (2014). On the network topology of variance decompositions: Measuring the connectedness of financial firms. Journal of Econometrics, 182(1), 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediagbonya, V., & Tioluwani, C. (2023). The role of fintech in driving financial inclusion in developing and emerging markets: Issues, challenges and prospects. Technological Sustainability, 2(1), 100–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, T., & Gauer, L. (2019). The role of cryptocurrencies in portfolio diversification. Journal of Financial Markets, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Elu, J., & Williams, C. (2022). Cryptocurrencies as safe havens during financial crises: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Finance Research Letters, 45, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Esparcia, A., & López, J. (2023). The dynamics of cryptocurrency returns and their implications for portfolio management. International Review of Financial Analysis, 80, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Flavin, T., & Sheenan, L. (2025). Can green bonds be a safe haven for equity investors? International Journal of Finance & Economics, 30(3), 2270–2283. [Google Scholar]

- Gabauer, D. (2021). Dynamic connectedness of cryptocurrencies and conventional assets: A time-varying param-eter VAR approach. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 29, 100431. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Alana, L. A., & Monge, M. (2020). Crude oil prices and COVID-19: Persistence of the shock. Energy Research Letters, 1(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodell, J. W., & Goutte, S. (2021). Co-movement of COVID-19 and Bitcoin: Evidence from wavelet coherence analysis. Finance Research Letters, 38, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guesmi, K., Saadi, S., Abid, I., & Ftiti, Z. (2019). Portfolio diversification with virtual currency: Evidence from bitcoin. International Review of Financial Analysis, 63, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Lu, F., & Wei, Y. (2021). Capture the contagion network of bitcoin–Evidence from pre and mid COVID-19. Research in International Business and Finance, 58, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. B., Hassan, M. K., Rashid, M. M., & Alhenawi, Y. (2021). Are safe haven assets really safe during th2008 global financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic? Global Finance Journal, 50, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevey, D. (2018). Network analysis: A brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 6(1), 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L. (2024). The relationship between cryptocurrencies and convention financial market: Dynamic causality test and time-varying influence. International Review of Economics & Finance, 91, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Duan, K., & Mishra, T. (2021). Is Bitcoin really more than a diversifier? A pre-and post-COVID-19 analysis. Finance Research Letters, 43, 102016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T. L. D., Hille, E., & Nasir, M. A. (2020). Diversification in the age of the 4th industrial revolution: The role of artificial intelligence, green bonds and cryptocurrencies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 159, 120188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R., Kumar, S., Sood, K., Grima, S., & Rupeika-Apoga, R. (2023). A systematic literature review of the risk landscape in fintech. Risks, 11(2), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juškaitė, V., & Gudelytė-Žilinskienė, A. (2022). The speculative nature of cryptocurrencies: A review of the literature. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36(4), 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Khaki, A. R., Al-Mohamad, S., Jreisat, A., Al-Hajj, F., & Rabbani, M. R. (2022). Portfolio diversification of MENA markets with cryptocurrencies: Mean-variance vs higher-order moments approach. Scientific African, 17, e01303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliber, A., Marszałek, P., Musiałkowska, I., & Świerczyńska, K. (2019). Bitcoin: Safe haven, hedge or diversi-fier? Perception of bitcoin in the context of a country’s economic situation—A stochastic volatility approach. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 524, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y., & Lin, Y. (2021). FinTech as a buffer against financial volatility: Evidence from Asia-Pacific markets. Asian Economic Policy Review, 16(3), 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Koop, G., & Korobilis, D. (2014). A new index of financial conditions. European Economic Review, 71, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, G., Pesaran, M. H., & Potter, S. M. (1996). Impulse response analysis in nonlinear multivariate models. Journal of Econometrics, 74(1), 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutmos, D., King, T., & Zopounidis, C. (2021). Hedging uncertainty with cryptocurrencies: Is bitcoin your best bet? Journal of Financial Research, 44(4), 815–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y. H., Chen, H., & Chen, K. (2007). On the application of the dynamic conditional correlation model in estimating optimal time-varying hedge ratios. Applied Economic Letters, 14(7), 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T. L., Abakah, E. J. A., & Tiwari, A. K. (2021). Time and frequency domain connectedness and spillover among FinTech, green bonds and cryptocurrencies in the age of the fourth industrial revolution. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 162, 120382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letho, L., Chelwa, G., & Alhassan, A. L. (2022). Cryptocurrencies and portfolio diversification in an emerging market. China Finance Review International, 12(1), 20–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. (2024). Exploring the relationship between green bond pricing and ESG performance: A global analysis. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magableh, K. N. Y., Badwan, N., Al-Nimer, M., Al-Khazaleh, S., Abdallah-Ou-Moussa, S., & Chen, Y. (2025). Role of financial technology (FinTech) innovations in driving sustainable development: A comprehensive literature review and future research avenues. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariana, C. D., Ekaputra, I. A., & Husodo, Z. A. (2021). Are Bitcoin and Ethereum safe-havens for stocks during the COVID-19 pandemic? Finance Research Letters, 38, 101798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A., & Ashofteh, A. (2023). Enhancing portfolio management through AI-driven solu-tions: A FinTech perspective. Journal of Financial Technology, 8(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mensi, W., Al-Yahyaee, K. H., Al-Jarrah, I. M. W., Vo, X. V., & Kang, S. H. (2020). Dynamic volatility transmission and portfolio management across major cryptocurrencies: Evidence from hourly data. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 54, 101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, M. S., Afshan, S., Zaied, Y. B., & Staniewski, M. (2025). The resilience of green bonds during market turmoil: Implications for investors and policymakers. International Journal of Finance & Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milka, P. (2020). Speculation in the cryptocurrency market. The Review of Economics, Finance & Investments, 1(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. A., Adekoya, O. B., & Oliyide, J. A. (2021). Asymmetric spillovers between green bonds and commodities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 314, 128100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. A., Hasan, M., Arif, M., & Shahzad, S. J. H. (2020). Can bitcoin glitter more than gold for investment styles? SAGE Open, 10(2), 2158244020926508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, B., Mirza, N., Rizvi, S. K. A., Porada-Rochoń, M., & Itani, R. (2021). Is there a green fund premium? Evidence from twenty seven emerging markets. Global Finance Journal, 50, 100656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K. Q. (2022). The correlation between the stock market and Bitcoin during COVID-19 and other uncertainty periods. Finance Research Letters, 46, 102284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oche, A. (2020). Comparative analysis of green bond regimes in Nigeria and China. Journal of Sustainable Development Law and Policy (The), 11(1), 160–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladinni, A., & Odumuwagun, O. O. (2025). Enhancing cybersecurity in fintech: Safeguarding financial data against evolving threats and vulnerabilities. International Journal of Computer Applications Technology and Research, 14(1), 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, H. H., & Shin, Y. (1998). Generalized impulse response analysis in linear multivariate models. Economics Letters, 58(1), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D. T. N. (2025). The nonlinear fintech-financial stability nexus in Asia-Pacific and the Middle East: When institutional quality and financial efficiency matter. Research in International Business and Finance, 81, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M., Su, C. W., & Tao, R. (2021). BitCoin: A new basket for eggs? Economic Modelling, 94, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadugu, R., & Doddipatla, L. (2022). Emerging trends in fintech: How technology is reshaping the global financial landscape. Journal of Computational Innovation, 2(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, A., Brahim, M., Dogan, E., & Tzeremes, P. (2023). Analysis of the spillover effects between green economy, clean and dirty cryptocurrencies. Energy Economics, 120, 106594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., Tiwari, A. K., & Nasreen, S. (2024). Are FinTech, Robotics, and Blockchain index funds providing diversification opportunities with emerging markets? Lessons from pre and postoutbreak of COVID-19. Electronic Commerce Research, 24(1), 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, W. F. (1994). The sharpe ratio. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 21(1), 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., Yadav, M. P., & Kaur, B. (2025). ESG investing, digital transformation, and sustainable portfolio resilience. Annals of Financial Economics, 20(1), 215. [Google Scholar]

- Stensås, A., Nygaard, M. F., Kyaw, K., & Treepongkaruna, S. (2019). Can Bitcoin be a diversifier, hedge or safe haven tool? Cogent Economics & Finance, 7(1), 1593072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A. A., Ahmed, F., Kamal, M. A., Ullah, A., & Ramos-Requena, J. P. (2022). Is there an asymmetric relationship between economic policy uncertainty, cryptocurrencies, and global green bonds? Evidence from the United States of America. Mathematics, 10(5), 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urom, C. (2023). Time–frequency dependence and connectedness between financial technology and green assets. International Economics, 175, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., & Wang, C. (2023). How do Fintech and green bonds ensure clean energy production in China? Dynamics of green investment risk. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(57), 120552–120563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Xia, Y., Fu, Y., & Liu, Y. (2023). Volatility spillover dynamics and determinants between FinTech and traditional financial industry: Evidence from China. Mathematics, 11(19), 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R., Li, B., & Qin, Z. (2024). Spillovers and dependency between green finance and traditional energy markets under different market conditions. Energy Policy, 192, 114263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R., Yan, J., & Işık, C. (2025). The dynamics between clean energy, green bonds, grain commodities, and cryptocurrencies: Evidence from correlation and portfolio hedging. Economic Change and Restructuring, 58(4), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M., David, J. M., & Kim, S. H. (2018). The fourth industrial revolution: Opportunities and challenges. International Journal of Financial Research, 9(2), 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M. P., Pandey, A., Taghizadeh-Hesary, F., Arya, V., & Mishra, N. (2023). Volatility spillover of green bond with renewable energy and crypto market. Renewable Energy, 212, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousfi, M., & Bouzgarrou, H. (2024). Geopolitical risk, economic policy uncertainty, and dynamic connectedness between clean energy, conventional energy, and food markets. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 31(3), 4925–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zen, F., & Saputra, W. (2023). Enhancing climate-resilient infrastructure development in Indonesia. Infrastructure for Inclusive Economic Development, 1, 193–215. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P., Xu, K., & Qi, J. (2023). The impact of regulation on cryptocurrency market volatility in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic—Evidence from China. Economic Analysis and Policy, 80, 222–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M., & Park, H. (2024). Quantile time-frequency spillovers among green bonds, cryptocurrencies, and conventional financial markets. International Review of Financial Analysis, 93, 103198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F. (2025). The trend of digital finance: Unveiling the multidimensional network of cryptocurrency risk propagation. Applied Economics, 57(38), 5924–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) and Year | Asset Class/Theme | Objective/Focus | Methodology Used | Key Findings | Expanded Limitations/Gaps (Reviewer-Ready) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letho et al. (2022) | Crypto | Diversification role | Portfolio analysis | BTC enhances diversification intermittently | Uses static diversification tests; ignores time-varying dynamics and does not consider interdependence with digital or green assets. |

| Milka (2020) | Crypto | Speculative nature | Behavioral and speculative review | Crypto markets driven by speculation | Lacks empirical spillover modeling; does not incorporate multi-asset interactions or dynamic regime shifts. |

| (Hasan et al., 2021) | Crypto | Hedging during COVID-19 | Copula and hedging | BTC shows hedging ability in crisis | Limited to crisis-specific analysis; bilateral focus prevents understanding broader systemic linkages. |

| Goodell and Goutte (2021) | Crypto | Safe-haven properties | Wavelet coherence | BTC hedges equities during shocks | Wavelet produces correlations, not true directional spillovers; exclude FinTech and green instruments. |

| Mensi et al. (2020) | Crypto | Connectedness | Spillover index | Time-dependent hedging efficiency | Measure limited to crypto–crypto relationships; lacks cross-domain diversification analysis. |

| Pham (2025) | FinTech | Shock buffering | Volatility models | FinTech reduces volatility in APAC | Regional restriction; does not explore global connectedness or interaction with crypto/green markets. |

| Agarwal et al. (2024) | FinTech | AI-based portfolio enhancement | Multi-factor | FinTech improves efficiency | Conceptual focus; lacks empirical spillover assessment across sectors. |

| Jain et al. (2023) | FinTech | Inclusion and innovation | Empirical/qualitative | FinTech broadens access but adds contagion risk | No modeling of volatility transmission or inter-market dynamics. |

| Ramadugu and Doddipatla (2022) | FinTech | Cybersecurity and regulation | Regulatory review | Volatility from digital risks | Theoretical; no multi-asset or dynamic connectedness analysis. |

| Chopra et al. (2024) | FinTech (NFTs/Sta blecoins) | Portfolio effects | Portfolio models | New instruments reshape diversification | Narrow focus on niche assets; no broader ecosystem analysis. |

| Bhutta et al. (2022) | Green bonds | Sustainability and risk | Spillover tests | GBs moderately hedge volatility | Green bonds treated in isolation, ignoring emerging digital finance interactions. |

| Oche (2020) | Green bonds | Crisis behavior | Wavelet/GARCH | Regime-dependent spillovers | No cross-market integration with crypto or FinTech equities. |

| Meo et al. (2025) | Green bonds | Safe-haven tests | Connectedness | Mixed safe-haven evidence | Lacks broader financial ecosystem analysis; narrow asset coverage. |

| Rqgreen | Rfinx | Rmscid | Rmscie | Rspgsci | Rbitcoin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nobs | 1098 | 1098 | 1098 | 1098 | 1098 | 1098 |

| Minimum | −0.1224 | −0.1374 | −0.1044 | −0.1343 | −0.1252 | −0.4809 |

| Maximum | 0.0925 | 0.1056 | 0.0841 | 0.0691 | 0.0768 | 0.2372 |

| Mean | 0.0007 | 0.001 | 0.0005 | 0.0004 | 0.0002 | 0.0026 |

| Stdev | 0.012 | 0.0166 | 0.0106 | 0.0129 | 0.0142 | 0.048 |

| Skewness | −1.5085 | −1.1125 | −1.7243 | −1.6789 | −1.359 | −0.9628 |

| Kurtosis | 20.4159 | 12.1082 | 25.0212 | 17.8756 | 14.1281 | 11.9894 |

| Jarque–Bera Test | 19566 *** | 6965 *** | 29305 *** | 15198 *** | 9511.2 *** | 6776.5 *** |

| ADF-Test | −9.229 *** | −9.345 *** | −9.3345 *** | −9.8139 *** | −9.5854 *** | −9.7308 *** |

| QGREEN | FINX | Bitcoin | MSCID | MSCIE | FROM Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QGREEN | 34.26 | 20.26 | 0.53 | 30.1 | 14.84 | 65.74 |

| FINX | 23.13 | 39.88 | 0.84 | 23.39 | 12.77 | 60.12 |

| Bitcoin | 0.63 | 0.97 | 97.06 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 2.94 |

| MSCID | 30 | 20.41 | 0.48 | 34.04 | 15.08 | 65.96 |

| MSCIE | 20.12 | 15.64 | 0.53 | 20.23 | 43.49 | 56.51 |

| TO Others | 73.88 | 57.27 | 2.38 | 74.44 | 43.3 | 251.27 |

| NET | 8.15 | −2.85 | −0.56 | 8.48 | −13.21 | TCI = 50.25 |

| Mean | Std. Dev. | 5% | 95% | HE | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QGREEN | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.24 | −2.05 | 0.000 |

| FINX | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.27 | −0.6 | 0.000 |

| Bitcoin | 0.39 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.81 | 0.000 |

| MSCID | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.17 | −2.93 | 0.000 |

| MSCIE | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.27 | −1.66 | 0.000 |

| QGREEN | FINX | Bitcoin | MSCID | MSCIE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.061 | 0.062 | 0.055 | 0.046 | 0.033 |

| Overall Sharpe ratio | 0.076 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aggarwal, V.; Sharma, S.; Bhatia, P.; Bhardwaj, I.; Na, R.; Sharma, S. Portfolio Diversification with Non-Conventional Assets: A Comparative Analysis of Bitcoin, FinTech, and Green Bonds Across Global Markets. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120687

Aggarwal V, Sharma S, Bhatia P, Bhardwaj I, Na R, Sharma S. Portfolio Diversification with Non-Conventional Assets: A Comparative Analysis of Bitcoin, FinTech, and Green Bonds Across Global Markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(12):687. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120687

Chicago/Turabian StyleAggarwal, Vaibhav, Sudhi Sharma, Parul Bhatia, Indira Bhardwaj, Reepu Na, and Shashank Sharma. 2025. "Portfolio Diversification with Non-Conventional Assets: A Comparative Analysis of Bitcoin, FinTech, and Green Bonds Across Global Markets" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 12: 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120687

APA StyleAggarwal, V., Sharma, S., Bhatia, P., Bhardwaj, I., Na, R., & Sharma, S. (2025). Portfolio Diversification with Non-Conventional Assets: A Comparative Analysis of Bitcoin, FinTech, and Green Bonds Across Global Markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(12), 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120687