1. Introduction

In today’s increasingly uncertain environment, corporate management faces significant challenges due to the heightened risk of bankruptcy arising from deteriorating business performance. Bankruptcies impose substantial losses on stakeholders, including business partners, investors, and financial institutions. Accordingly, developing models that prevent or enable the early detection of bankruptcy has become essential. While traditional research has relied on statistical approaches, recent advances in machine learning have enabled more objective and accurate predictions.

This study builds on earlier work by applying ensemble learning methods—Random Forest and LightGBM—while addressing key challenges such as feature selection, imbalanced data, and industry-specific modeling. In particular, the study integrates resampling techniques with stepwise feature selection, thereby enhancing model generalization, interpretability, and the ability to uncover sector-specific bankruptcy patterns.

Corporate bankruptcy prediction has long been an important research topic in accounting, finance, and risk management. Early foundational studies, including

Beaver (

1966),

Altman (

1968),

Ohlson (

1980), and

Zmijewski (

1984), demonstrated the predictive power of financial ratios through discriminant and probit/logit models (

Nam & Jinn, 2000). Subsequent refinements introduced hazard models (

Shumway, 2001), the incorporation of industry effects (

Chava & Jarrow, 2004), and market-based indicators (

Hillegeist et al., 2004;

Y. Wu et al., 2010). Altman and colleagues later expanded the Z-score model to non-manufacturing firms, private companies, and emerging markets, improving its general applicability (

Altman et al., 2017). These early frameworks established the theoretical basis for risk classification and default probability estimation in corporate finance.

As data availability and computational power increased, the field transitioned toward machine learning–based approaches.

F. Y. Lin and McClean (

2001) and

Varetto (

1998) applied data mining and genetic algorithms, while

L. Sun and Shenoy (

2007) introduced Bayesian networks for bankruptcy prediction.

Z. Huang et al. (

2004) compared support vector machines and neural networks for credit rating analysis, showing the potential of non-linear models in financial risk assessment.

Choi and Lee (

2018) advanced this further by applying multi-label learning to handle multiple bankruptcy indicators simultaneously. These studies highlighted both the interpretability and flexibility of machine learning in capturing complex financial patterns.

Since the 2000s, ensemble learning methods have become central to bankruptcy prediction.

Breiman’s (

2001) Random

Forest and Dietterich’s (

2000) ensemble strategies demonstrated the advantages of combining multiple classifiers for robustness. Boosting algorithms, including AdaBoost (

Heo & Yang, 2014), Gradient Boosting (

Chen & Guestrin, 2016), and LightGBM (

Ke et al., 2017), achieved high predictive performance and scalability. Hybrid ensemble frameworks integrating multiple learners further improved generalization (

Wang et al., 2010;

L. Tang & Yan, 2021;

Yu & Zhang, 2020). CatBoost-based models also contributed to improved accuracy in recent studies (

Jabeur et al., 2021;

Mishra & Singh, 2022). Comparative research consistently confirmed that ensemble models outperform single classifiers in both stability and predictive capability (

Bandyopadhyay & Lang, 2013;

Lahsasna et al., 2018;

C.-C. Lee & Chen, 2020;

Kraus & Feuerriegel, 2019;

Guillén & Salas, 2021). Furthermore, stacking and meta-learning approaches have been proposed to exploit complementary model strengths (

Tsai & Hsu, 2013;

Y. Tang et al., 2009). Studies such as

S. Lee and Choi (

2013) emphasized that incorporating sectoral heterogeneity enhances predictive realism.

Another methodological challenge involves imbalanced data, as bankruptcies occur far less frequently than solvent cases. Class imbalance often inflates accuracy metrics while reducing sensitivity to true defaults (

He & Garcia, 2009;

J. Huang & Ling, 2005). To mitigate this, resampling strategies such as SMOTE (

Chawla et al., 2002), SMOTE-ENN (

Batista et al., 2004;

Y. Liu & Wu, 2021), and SMOTE-IPF (

Sáez et al., 2015) were developed. Exploratory undersampling methods (

X.-Y. Liu et al., 2009) and KMeans-based approaches offered alternatives to preserve data diversity. Subsequent studies validated these methods’ importance for balanced learning (

Fernández et al., 2018;

J. Sun et al., 2014). Neural network studies (

Buda et al., 2018) demonstrated imbalance sensitivity, while

Zhao and Wang (

2018) combined resampling and ensemble learning to enhance minority-class recognition. Recent work by

Ansah-Narh et al. (

2024) explored hybrid evolutionary algorithms with domain adaptation, further extending imbalance correction techniques.

Feature selection and dimensionality reduction also play essential roles in improving model interpretability and performance. While early research relied primarily on accounting ratios, later work incorporated broader information such as governance, market, and macroeconomic variables (

J. Sun et al., 2014;

Ciampi, 2015). Feature selection methods reduce noise and overfitting (

Guyon & Elisseeff, 2003;

Tsai, 2009) and help identify the most influential predictors. Hybrid strategies combining multiple selection criteria (

Ko et al., 2021;

Pramodh & Ravi, 2016;

Hossari & Rahman, 2022;

Kotze & Beukes, 2021;

García et al., 2019) further enhanced stability. Explainable AI techniques (

Lundberg & Lee, 2017;

Giudici & Hadji-Misheva, 2022;

C.-H. Yeh et al., 2022) and advances in interpretable modeling (

J. Wu & Wang, 2022;

Zhang & Wang, 2021) improved transparency in financial applications.

Dikshit and Pradhan (

2021) even demonstrated the applicability of interpretable models in environmental risk, underscoring the cross-domain potential of explainable AI.

Overall, the literature reveals a clear progression from interpretable statistical models to increasingly complex, data-driven, and explainable frameworks. Prediction success depends not only on algorithmic choice but also on handling imbalanced data, selecting informative features, and incorporating industry-specific determinants. Building on this understanding, the present study adopts a two-stage machine learning framework for bankruptcy prediction among Tokyo Stock Exchange–listed firms. In the first stage, comprehensive learning is performed using 173 financial indicators. In the second stage, wrapper-based feature selection is applied to gradually reduce dimensionality, eliminate noise, and arrive at an optimal seven-feature set. This approach enhances both predictive performance and interpretability.

To capture sector-specific heterogeneity, separate models are constructed for six industries—Construction, Real Estate, Services, Retail, Wholesale, and Electrical Equipment—thus uncovering sectoral bankruptcy determinants and patterns. In addition, three resampling techniques—SMOTE, SMOTE-ENN, and k-means clustering—are incorporated to address class imbalance. Empirical results reveal that Random Forest correctly predicts 566 bankruptcies and LightGBM predicts 451, both substantially outperforming models without feature reduction. By simultaneously addressing four key challenges—methodological choices, dataset design, class imbalance, and industry heterogeneity—this study underscores both its novelty and practical relevance.

3. Results

In this two-stage study, the results of the second stage are derived from a dataset of seven features obtained through progressive feature reduction in the 173-feature set used in the first stage. This eliminates noise and prevents overfitting. We use the feature importance attribute to determine which features the models rely on the most for bankruptcy prediction, quantifying each feature’s importance and visualizing the results.

3.1. First Stage Results (173 Features)

This section presents the results of the first stage of bankruptcy prediction. In the first stage, we construct bankruptcy prediction models using Random Forest and LightGBM with a dataset containing all 173 available financial indicators.

3.1.1. Random Forest

Table 4 presents the results obtained by dataset configuration using the 173-feature set. The total TP count across the financial, investment financing, and comparison datasets was 478. Among the datasets, the financial dataset, having the largest sample size, achieved the best prediction accuracy, with 284 TPs. Both the investment financing and comparison datasets yielded 97 TPs, indicating no apparent advantage in using investment financing network indicators.

Resampling: For the 317 bankrupt companies across the six industries (

Table 5), k-means achieved the highest accuracy with 186 TPs across all three datasets, followed by SMOTE-ENN with 177 TPs, and SMOTE with 115 TPs.

Industry-Specific Results:

Table 6 presents the industry-specific prediction results by dataset configuration. The highest TP count (75) was recorded in the construction industry when the financial dataset was used. By contrast, the lowest TP count (0) was recorded for the wholesale industry when using the comparison dataset.

Resampling Results by Industry:

Table 7 presents the resampling results by industry. Applying k-means resampling to the construction industry data yielded the highest TP count (59), whereas applying SMOTE resampling to the wholesale industry data produced the lowest TP count (3).

Taken together, the results in

Table 6 and

Table 7 show that applying Random Forest to the data from the construction industry yields the highest total TP count (152), whereas applying this method to the wholesale industry data produces the lowest total TP count (21). Recall was highest in the real estate industry (58.33%) and lowest in the wholesale industry (26.92%).

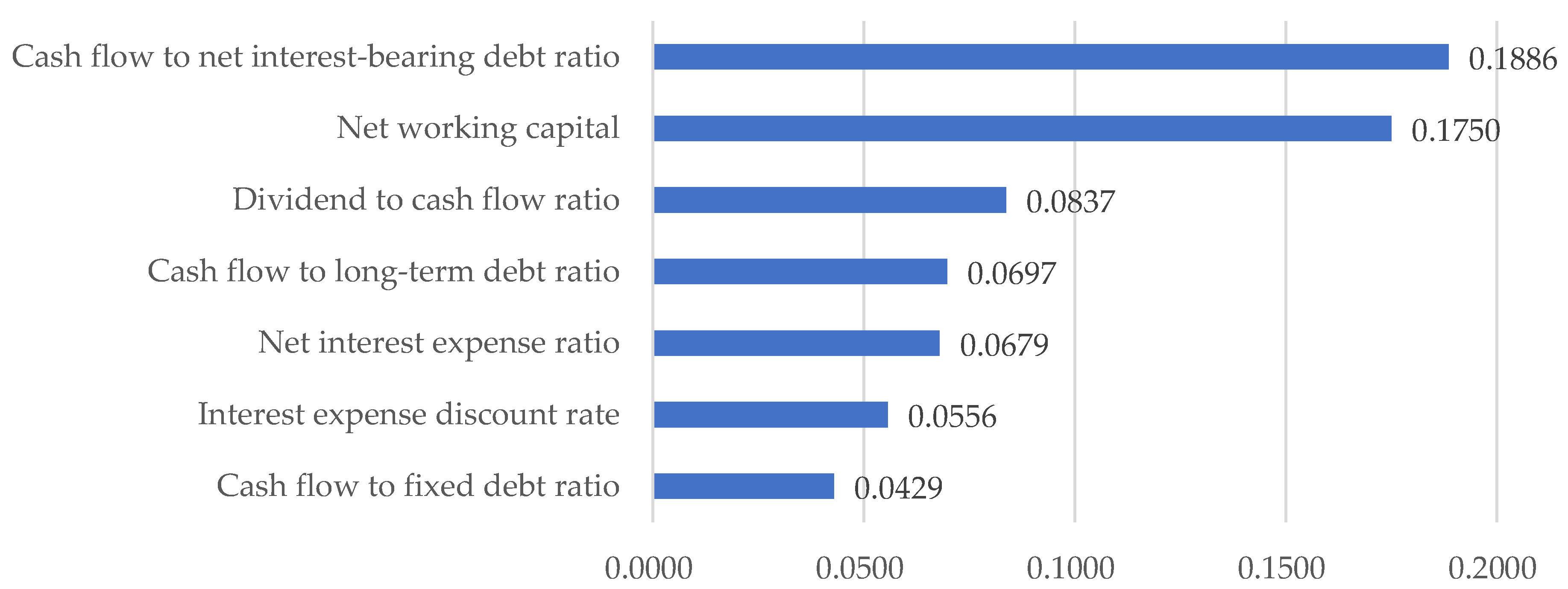

Feature Importance: To pinpoint which features were significant for the model’s predictions, we visualized the feature importance scores assigned by the Random Forest algorithm.

Figure 1 illustrates the top seven features (out of 173) for the electrical-equipment industry using the financial dataset with SMOTE-ENN resampling.

3.1.2. LightGBM

Table 8 presents the results obtained using 173-feature set. Across the financial, investment-financing, and comparison datasets, Random Forest correctly identified 420 bankrupt firms, 58 more than LightGBM. When broken down by dataset, Random Forest achieved its highest TP count on the financial dataset, which had the largest sample size with 264 TPs, and identified 58 bankrupt firms using the investment-financing dataset and 97 using the comparison dataset. Notably, we found no significant differences between the investment-financing dataset and the comparison dataset when using Random Forest. However, a difference emerged with LightGBM. For LightGBM, incorporating network indicators resulted in worse performance.

Resampling: Looking at the resampling results across six industries covering 317 bankrupt companies in total, SMOTE-ENN achieved the highest accuracy with 149 TPs, followed by SMOTE with 141 TPs, and K-means with 129 TPs (

Table 9).

Industry-Specific Results:

Table 10 presents the prediction results categorized by industry and dataset configuration. The financial dataset for the real estate industry produced the highest TP count with 62 companies, whereas the investment-financing dataset for the electrical equipment industry showed the lowest TP count of 0.

Resampling Results by Industry:

Table 11 presents the resampling results for each industry. The highest TP count (49) was generated by the construction industry using SMOTE-ENN. Conversely, the lowest TP count (11) is observed for the service industry using both SMOTE-ENN and k-means.

The combined results in

Table 10 and

Table 11 show that, when using LightGBM, 139 TPs were generated for the real estate industry. By contrast, the lowest TP count (34) was observed in the service industry. Recall was highest in the real estate industry (60.96%) and lowest in the wholesale industry (24.30%).

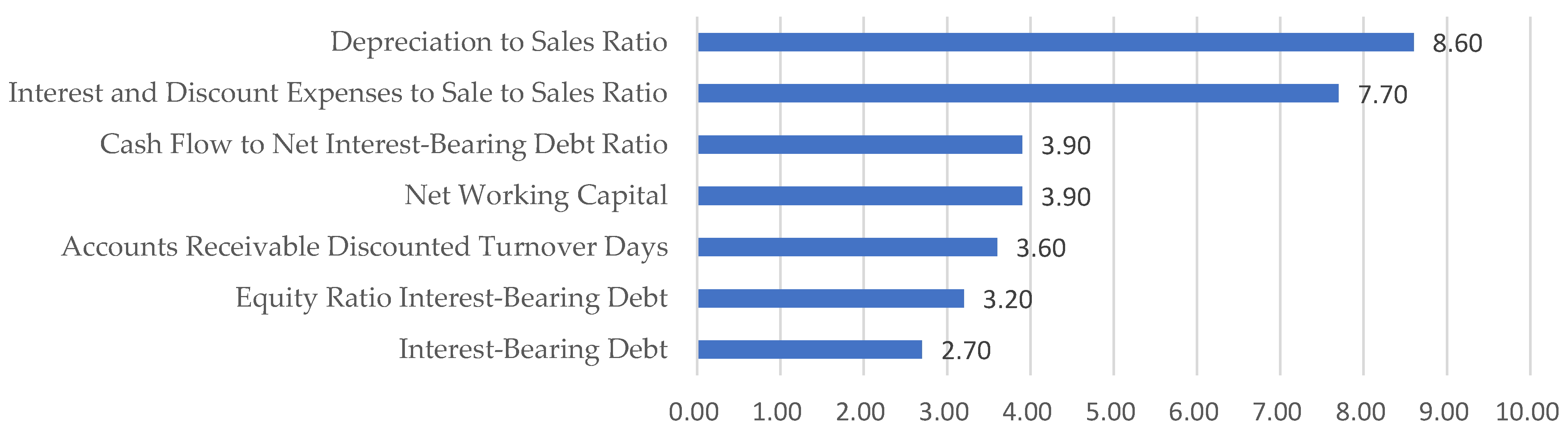

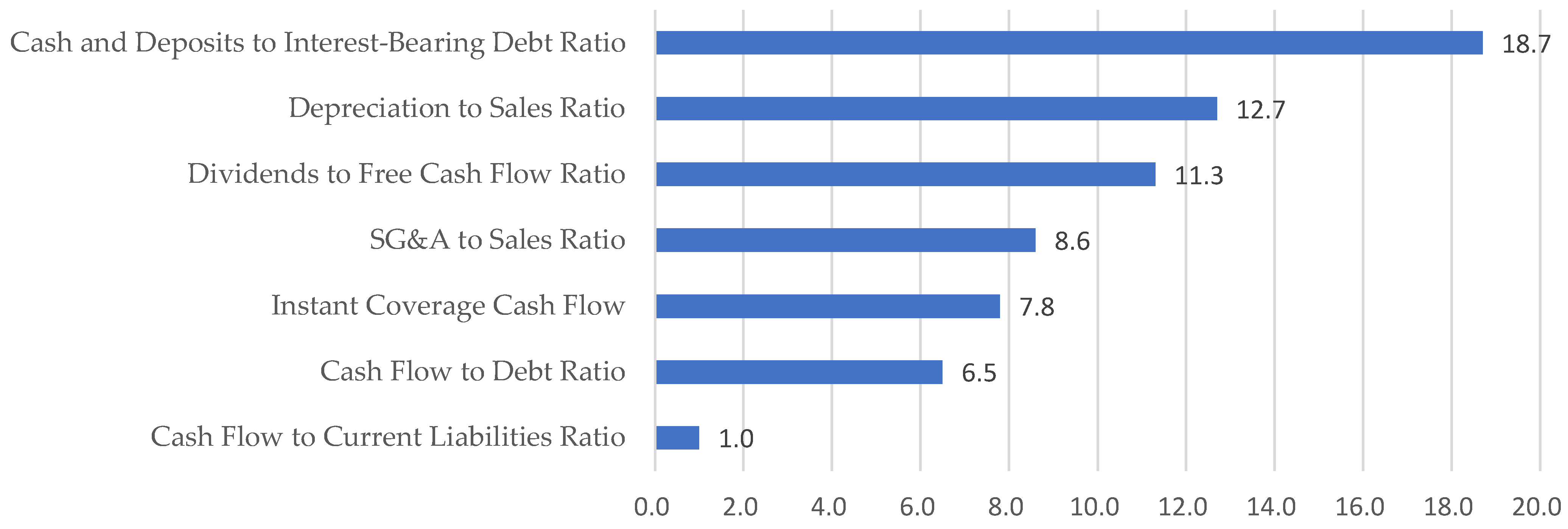

Feature Importance: To identify the features that were significant for the model’s predictions, we visualized the feature importance scores assigned by LightGBM.

Figure 2 illustrates the top seven features (out of 173) for the electrical-equipment industry using the financial dataset processed using SMOTE-ENN.

3.2. Second-Stage Analysis Results (7 Features)

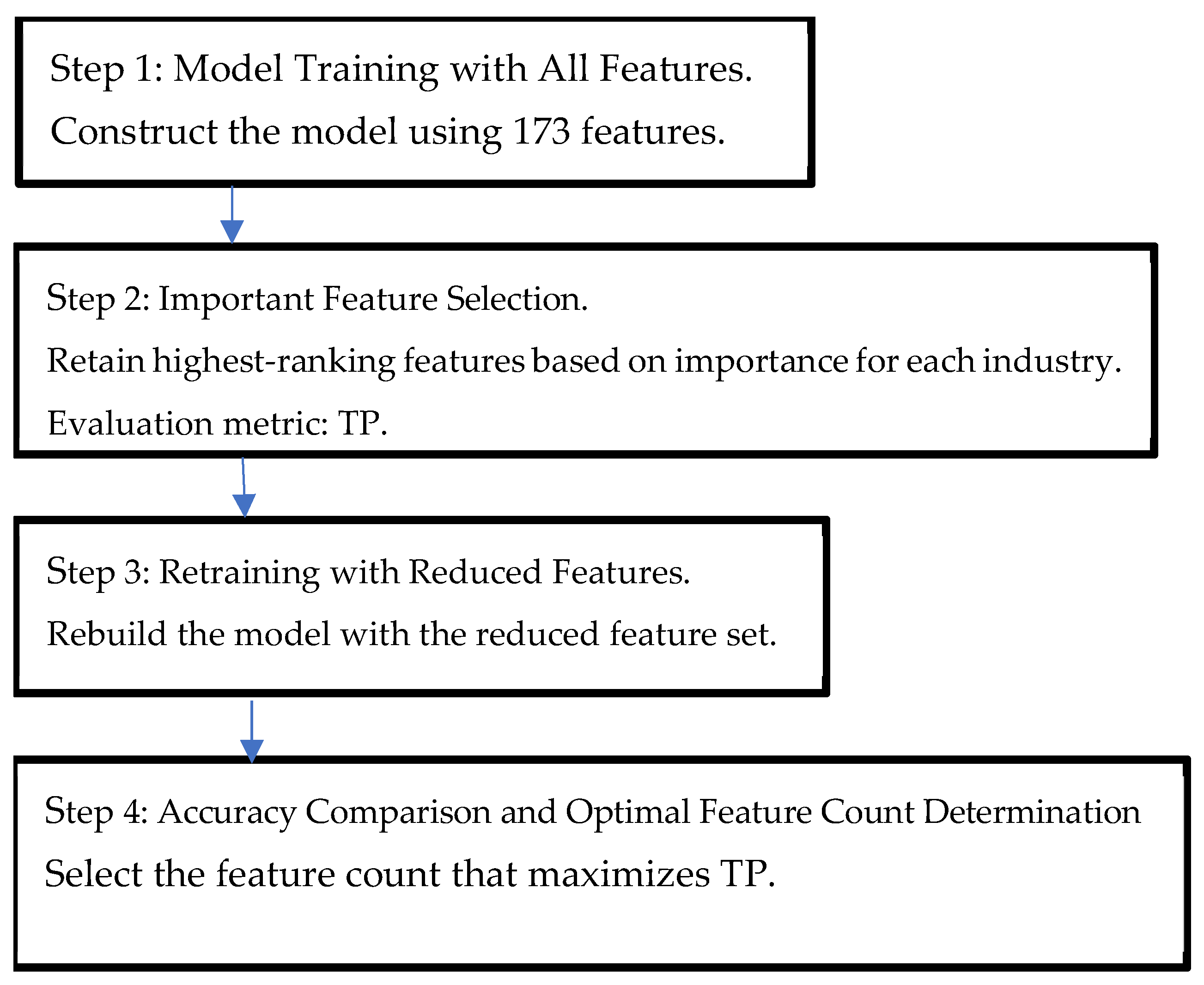

This study proposes a two-stage bankruptcy prediction model using financial data from listed Japanese companies. The first stage involves model training with all 173 available financial indicators. The second stage improves predictive accuracy through passive dimensionality reduction to eliminate noise and prevent overfitting. It applies feature selection using Random Forest and LightGBM to iteratively reduce the feature set from 173 to a smaller optimal subset, thereby enhancing the model’s performance in identifying bankrupt firms.

We explicitly define the threshold criteria for feature removal. Specifically, features with an importance ratio below a predefined level (e.g., 1% of cumulative importance) are sequentially removed in each iteration. To ensure reproducibility, the procedure terminates when the improvement in validation accuracy remains below 0.5% for three consecutive iterations. Furthermore, we clarify the evaluation of the trade-off between model complexity and predictive performance by monitoring both the number of selected features and the corresponding changes in the F1 score and Cohen’s Kappa value. These refinements render the selection logic transparent and empirically robust.

The feature selection process follows a wrapper-based approach involving iterative model training and evaluation based on the true positive (TP) count and recall to identify the optimal number of features for each industry category. The procedure is summarized as follows:

Step 1: Train the model using all 173 features.

Step 2: Based on performance (TP count), remove less important features and retain the top-ranked features for each industry.

Step 3: Train a new model using the reduced feature set.

Step 4: Repeat Steps 2 and 3 until the TP count reaches its maximum; this point determines the optimal feature set.

Among the seven selected features, Random Forest achieves 566 TPs, whereas LightGBM achieves 451. Thus, the Random Forest model predicts 115 more bankruptcies. In contrast, when all 173 features are used, Random Forest predicts 478 bankruptcies and LightGBM predicts 420. These results demonstrate that, by employing the wrapper-based approach—the key methodological contribution of this study—we effectively reduce dimensionality, eliminate noise, and improve model performance.

Table 12 and

Figure 3 show how the TP count changes as the number of features is progressively reduced from 173 to two through feature selection, representing the sum of the SMOTE, SMOTE+ENN, and k-means results.

3.2.1. Random Forest

Table 13 presents the results generated using the 7-feature set. The total TP count across the financial, investment financing, and comparison datasets was 566. By contrast, as mentioned previously, when all 173 features were used, Random Forest achieved 478 TPs. This demonstrates that using the seven selected features predicted 88 more bankruptcies (566 vs. 478 TPs) with Random Forest than using all 173 features. Thus, we successfully achieved our study’s objective of improving bankruptcy prediction accuracy. Considering the results by dataset configuration, the financial dataset, which had the largest sample size, showed the best prediction accuracy, with 303 TPs. The model produced 142 TPs with the investment financing dataset and 121 TPs with the comparison dataset, which demonstrates the added value of incorporating investment financing network indicators.

Resampling: SMOTE-ENN resampling achieved the highest accuracy, with 211 TPs across all three datasets combined (

Table 14). K-means followed with 206 TPs and SMOTE with 149 TPs. In comparison, when all 173 features were used, SMOTE, SMOTE-ENN, and K-means achieved 115, 177, and 186 TPs, respectively, indicating improvements of 34, 34, and 20 additional TPs, respectively, with the seven-feature set compared with all 173 features.

As shown in

Table 15, the Random Forest model achieved the highest number of TPs when applied to the financial dataset of the construction industry. Specifically, it correctly identified 87 bankrupt firms out of 126 actual bankruptcies. In contrast, the comparative dataset exhibited the lowest performance in the service industry, with only two TPs.

Resampling Results by Industry:

Table 16 presents the resampling results for each industry. In the construction industry, SMOTE-ENN yields the highest TP count of 67. Conversely, for the wholesale industry, using SMOTE resulted in the lowest TP count at only 12.

The combined results in

Table 15 and

Table 16 indicate that the highest TP count (172) was recorded for the construction industry, whereas the lowest TP count (48) was recorded for the wholesale industry. In terms of recall, the highest rate (68.86%) was observed for the real estate industry data, whereas the lowest rate (54.29%) was observed for the service industry data.

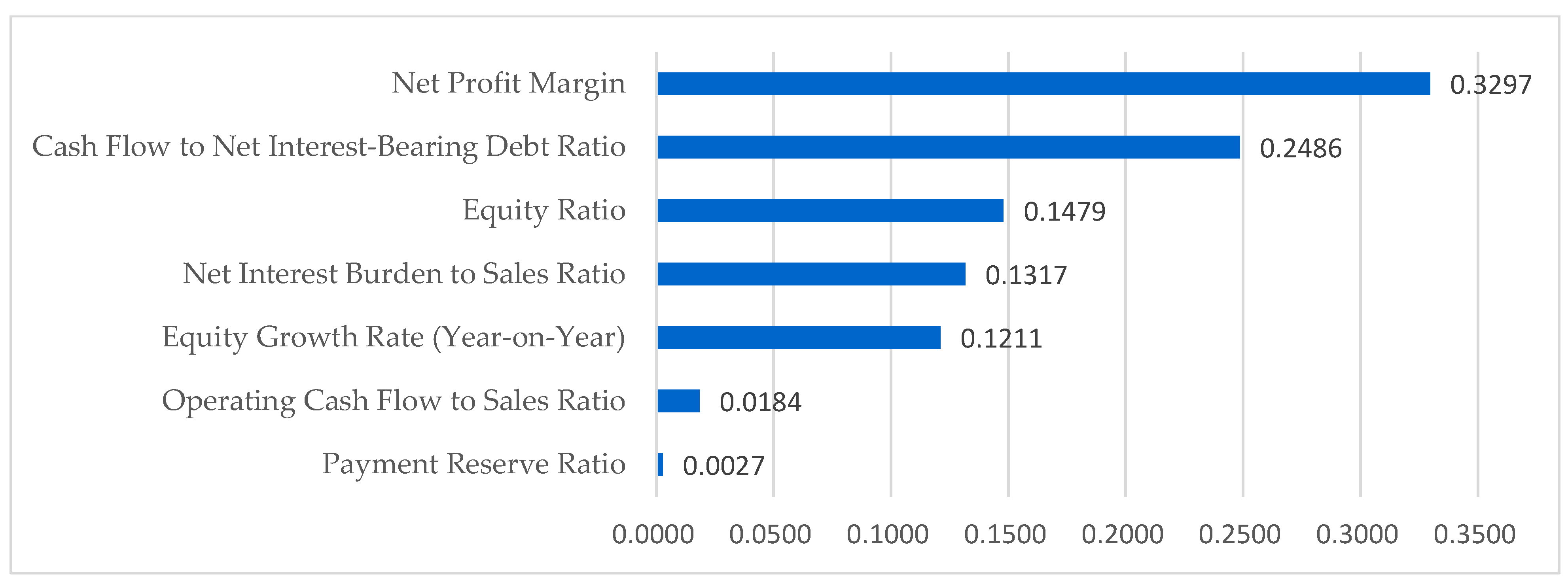

Feature Importance:

Table 17 compares the top seven features identified by Random Forest from the full 173-feature set with the seven features selected for the optimized model. This table highlights the top seven features selected from the original 173 features for comparison.

Notably, no network indicators were selected among the final seven features, and all the selected features were financial indicators. Furthermore, Cash Flow to Net Interest-Bearing Debt Ratio and Net Interest Burden to Sales Ratio appear among the seven selected features and among the top seven indicators of the 173-feature set, demonstrating their importance for bankruptcy prediction with Random Forest. Moreover, when using the seven-feature set, two cash flow indicators are included: cash flow to net interest-bearing debt ratio and operating cash flow to sales ratio. When using all 173 features, four of the top seven features are cash flow-related: the Cash Flow to Net Interest-Bearing Debt Ratio, Dividends to Cash Flow Ratio, Cash Flow to Long-Term Debt Ratio, and Cash Flow to Fixed Liabilities Ratio. Given that cash shortages are often the primary cause of corporate bankruptcy, this finding indicates that the model successfully identifies the relevant features.

For the electrical equipment industry,

Figure 4 presents the importance scores of the top seven features computed on the financial dataset following SMOTE-ENN resampling.

3.2.2. LightGBM

Table 18 presents the results obtained using these seven features. Among the datasets, the highest prediction accuracy for 283 TPs was achieved using the financial dataset with the largest sample size.

Table 19 presents Resampling: Across all six industries and three dataset configurations (encompassing 317 bankrupt companies in total), SMOTE resampling achieved the highest accuracy with 199 TPs, followed by SMOTE-ENN with 191 TPs, and k-means with 61 TPs.

Industry-Specific Results: As shown in

Table 20, for LightGBM, the highest TP count (72) is achieved using the financial dataset for the real estate industry, whereas the lowest TP count of 2 is observed when using the investment-financing dataset for the retail industry.

Resampling Results by Industry: As shown in

Table 21, which presents the LightGBM resampling results by industry, SMOTE-ENN yielded 60 TPs with data for the real estate industry. K-means showed the worst performance with the electrical equipment industry data at zero TPs.

As the combined results in

Table 20 and

Table 21 show, when the seven-feature LightGBM model is applied across industries, the highest TP count (138) is predicted for the real estate industry. Conversely, the lowest TP count of 43 is predicted for the service industry. In terms of recall, the highest rate was recorded for the construction industry (68.57%), whereas the lowest rate was observed for the wholesale industry (33.70%).

Feature Importance:

Table 22 presents a comparison of the top seven features identified by LightGBM from the full 173-feature set with the seven features selected for the optimized model. The Depreciation to Sales ratio feature appears in both the seven selected features and the top seven of the full set, underscoring its critical role in LightGBM-based bankruptcy prediction. In the seven-feature model, four cash flow metrics were selected (dividend-to-free cash flow ratio, instant coverage cash flow, cash flow to debt ratio, and cash flow to current liabilities ratio), whereas in the full 173-feature ranking, the Cash Flow to Net Interest-Bearing Debt Ratio also emerged among the top indicators. Given that insufficient cash flow is the leading cause of corporate bankruptcies, these results confirm that the proposed approach effectively identified relevant features.

Figure 5 illustrates the top seven features (out of 173) for the electrical equipment industry when using a financial dataset processed with SMOTE-ENN.

4. Discussion

This study proposed a two-stage machine learning framework to address several challenges inherent in corporate bankruptcy prediction, including high-dimensional financial data, class imbalance, industry heterogeneity, and the need for interpretability. Through extensive analyses using Random Forest and LightGBM, our findings demonstrate that the proposed approach is both effective and practically applicable. A key contribution of this research is the significant improvement achieved through feature selection. By reducing the original 173 financial indicators to an optimized subset of only seven features, the model not only became more interpretable but also achieved higher predictive performance. The research also demonstrated the superior performance of Random Forest over LightGBM, with the former achieving 566 true positives using a seven-feature set, an improvement of 88 cases compared with the full feature set. This result suggests that many of the original features may have introduced noise, and that carefully removing low-importance variables helps strengthen the model’s ability to identify bankruptcy-prone firms. The selected features commonly reflected profitability, liquidity, leverage, and cash-flow stability—factors widely recognized as fundamental indicators of corporate financial health. The industry-specific analysis revealed substantial differences in bankruptcy determinants across sectors. In construction and real estate, capital structure and fixed-asset intensity played more dominant roles, whereas in wholesale and service sectors, short-term liquidity and working capital were more influential. These results show that bankruptcy mechanisms differ across industries, reinforcing the importance of evaluating each sector independently rather than applying a uniform model to all firms. Our evaluation of resampling techniques further highlighted the interaction between algorithm choice and data-balancing strategy. For Random Forest, k-means undersampling provided the strongest performance, whereas SMOTE-ENN yielded the best results for LightGBM. This suggests that the effectiveness of resampling methods depends heavily on how each algorithm handles noise, boundary samples, and minority-class representation. About the issue of generalizability, we have clarified that the industry-specific models are designed explicitly to improve predictive accuracy and interpretability within each industry. They are not intended to be generalized across different industries. Because financial structures, operational characteristics, and bankruptcy mechanisms differ substantially among industries, applying a model trained in one industry to another would be inappropriate. This heterogeneity is precisely why separate models were developed. This study has several limitations. First, the dataset consists solely of Japanese listed firms, which may limit the applicability of the findings to firms in other countries or to small and medium-sized enterprises. Second, formal statistical significance tests such as the McNemar test were not conducted due to data constraints; future research should investigate the statistical robustness of the observed performance improvements. Third, feature selection was conducted using ensemble tree-based models; comparisons with other model families, such as SVMs or neural networks, were beyond the scope of this study and remain an area for future work. Despite these limitations, the proposed two-stage framework provides a practical and interpretable approach to bankruptcy prediction, combining the strengths of ensemble learning, feature selection, and industry-specific modeling. The findings offer valuable insights for academics and practitioners involved in credit risk assessment, financial monitoring, and early warning systems.

5. Conclusions

This study develops a two-stage machine learning framework for predicting corporate bankruptcy by integrating ensemble learning, feature selection, and resampling techniques. The proposed model effectively addresses key challenges in bankruptcy prediction, including high-dimensional financial data, class imbalance, and the need for industry-specific interpretability. By combining Random Forest and LightGBM with wrapper-based feature selection, the approach reduces the original 173 financial indicators to a smaller, optimal set of features, thereby improving both predictive accuracy and model transparency.

The results demonstrate that the proposed model not only enhances classification performance but also improves interpretability by identifying the most critical financial indicators associated with profitability, liquidity, leverage, and cash flow stability. Furthermore, the construction of industry-specific models based on the Tokyo Stock Exchange classification provides valuable insights into financial patterns that characterize bankruptcy risks across different sectors. These findings contribute to both academic research and practical applications by presenting a robust and interpretable predictive framework that bridges methodological rigor and real-world utility.

From a practical perspective, the model offers an efficient and transparent framework for credit risk evaluation and early warning systems. Financial institutions can utilize the reduced feature set to streamline credit screening and enhance decision-making. Investors and regulators can apply the model to detect early signs of financial distress and strengthen macroprudential oversight, thereby supporting more proactive risk management and corporate monitoring.

Future research can expand upon this study by incorporating a broader range of firms and time periods to test the generalizability of the model. Extending the analysis to include macroeconomic variables and external financial conditions may further improve predictive accuracy and explainability. In addition, future work could explore the integration of deep learning architectures or hybrid ensemble techniques to capture non-linear relationships in financial distress prediction. These extensions would further enhance the applicability, scalability, and robustness of the proposed framework, supporting continuous innovation in data-driven financial risk management.