Abstract

This study investigates how the Egyptian stock market responded to the 2024 devaluation of the Egyptian Pound (EGP) and evaluates whether price adjustments reflect semi-strong form market efficiency. Using daily data for EGX30 firms, we estimate abnormal returns around the devaluation announcement and document largely insignificant market-wide reactions, indicating weak evidence of semi-strong efficiency. However, notable cross-firm heterogeneity emerges export-oriented and foreign-revenue-generating firms showed greater resilience, while companies dependent on imported inputs experienced sharper declines. These findings highlight how differences in currency exposure shape firms’ sensitivity to exchange rate shocks in emerging markets with recent dual-rate dynamics. From a practical perspective, the results emphasise the importance of transparent policy communication during major currency adjustments and underline the need for investors to account for firms’ FX risk profiles when constructing portfolios in devaluation-prone environments. The findings also offer insights for regulators seeking to strengthen disclosure practices and improve informational efficiency in the Egyptian capital market.

1. Introduction

In emerging market economies, exchange rate dynamics play a critical role in shaping investor behaviour and financial market performance. Egypt, a country frequently navigating political and economic turbulence—including the 2011 revolution, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the 2022 Russia–Ukraine crisis—has experienced recurrent currency pressures. These crises collectively contributed to a significant decline in foreign currency reserves, prompting the government to implement multiple devaluations of the Egyptian Pound (EGP). In early 2024, the state formally adopted a free-float exchange rate regime in response to a widening gap between official and parallel market rates. While this step aimed to stabilize currency expectations, the devaluation’s impact on capital markets, particularly stock returns, remains underexplored.

This study investigates how Egyptian stock returns responded to the 2024 devaluation announcement, shedding light on market efficiency and investor reaction to macroeconomic shocks. Emerging markets like Egypt combine shallower liquidity, episodic policy shifts, and information frictions, potentially altering the speed of price discovery relative to developed markets. This makes Egypt a salient test bed for semi-strong efficiency around policy-driven devaluation announcements. Egypt’s exchange rate regime has undergone successive adjustments since 2016, alternating between managed and more flexible arrangements. The March 2024 devaluation marked a decisive step toward unifying the official and parallel market rates following a prolonged dual-rate period. Such regime shifts can reset investor beliefs about FX availability, capital flows, and firm cost structures. Hence, the announcement provides a clean setting to examine how quickly and completely equity prices incorporate major policy information.

Devaluation events carry substantial implications for firms listed on the stock exchange by altering cash flow expectations, discount rates, and the valuation of real assets (Chortareas et al., 2012). Exchange rate movements can either enhance firm competitiveness—especially for exporters—or introduce additional risk and cost pressures, particularly for import-dependent firms. Several theoretical models help frame this complex relationship. The flow-oriented model (Dornbusch & Fischer, 1980) posits that depreciation of the local currency stimulates exports and trade balance, leading to increased production and corporate profitability. In contrast, the portfolio rebalancing model (Hau & Rey, 2004; Ding, 2021) suggests that foreign stock market movements influence currency values through cross-border capital flows, highlighting how international investor sentiment interacts with domestic financial assets.

Despite these theoretical insights, emerging markets such as Egypt pose unique challenges to informational efficiency, particularly in the face of policy-driven shocks like currency devaluation. As currency risk increases, foreign investors may become more cautious, especially in contexts where market mechanisms for price discovery are underdeveloped or distorted by informal information channels. The persistent declines in the EGP may erode investor confidence in local markets, with implications for capital inflows and market stability. These dynamics underscore the importance of empirically evaluating how stock prices respond to devaluation events, not only to assess market efficiency but also to guide regulatory and policy frameworks.

This study is guided by two theoretical perspectives: the flow-oriented model (Dornbusch & Fischer, 1980), which suggests that depreciation improves competitiveness and firm performance, and the portfolio rebalancing model (Hau & Rey, 2004), which emphasizes investor capital flow responses. These frameworks underpin our interpretation of firm-level abnormal returns post-devaluation.

Against this backdrop, the present study applies an event study methodology to test the semi-strong form efficiency of the Egyptian stock market by examining stock price reactions to the 2024 devaluation announcement. Two distinct windows are analysed: an estimation period (9 December 2023–6 February 2024) and an event window (7 February 2024–3 April 2024). The event study approach provides a robust framework for detecting abnormal stock returns surrounding the announcement date, offering insights into the speed and completeness with which market participants incorporate new macroeconomic information.

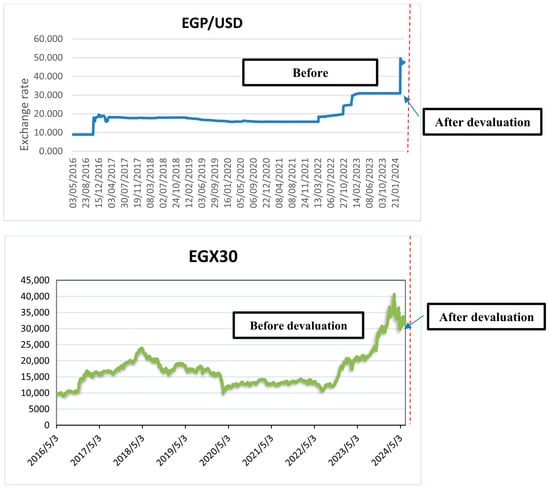

This empirical setting allows us to contribute to several important areas. First, the analysis tests whether the market efficiently responds to exchange rate news, an area of growing interest given Egypt’s ongoing macroeconomic volatility. Second, by disaggregating the results across firms, we explore the differential effects of devaluation based on likely exposure to exchange rate risk. Figure 1 illustrates that while the currency exhibited signs of stabilization post-devaluation, the EGX30 index began to decline, raising concerns about investor sentiment and the potential long-term effects on foreign investment.

Figure 1.

Time trend of EGP/USD and EGX30 index from (2016–2024). Market index after the devaluation (t = 0 to +20), indicated by the sharp increase at the end of the series.

We find evidence of weak semi-strong efficiency: most firms experienced statistically insignificant abnormal returns around the devaluation event. However, notable pre-event price movements suggest partial anticipation by market participants. These findings carry practical implications for market regulation, investor protection, and policy communication strategies in contexts where currency risk is high and formal information channels may be insufficiently robust.

This paper makes four contributions. First, it empirically tests the semi-strong form efficiency of the Egyptian stock market using a major macroeconomic event—the 2024 devaluation announcement—as the focal point. Second, the results offer predictive insights into how currency devaluation indirectly affects stock performance, providing investors with tools to manage exchange rate risks through instruments such as financial derivatives. Third, the paper applies a well-established event study design to divide the observation period into estimation and event windows, enabling a clear comparison of price behavior across time. Finally, to the best of our knowledge, this is one of the few studies within the MENA region (Middle East and North Africa) to examine the immediate market response to devaluation, helping to clarify the short-term relationship between exchange rate movements and stock returns in an emerging market context.

This study provides the first empirical examination of the 2024 EGP devaluation’s immediate impact on firm-level stock returns in Egypt, offering new insights into how investor expectations and sectoral exposure (e.g., import dependency vs. foreign revenue streams) mediate abnormal returns.

Egypt’s stock market serves as a key channel for price discovery and capital allocation, particularly for large and liquid issuers represented in the EGX30. Our final sample includes 29 EGX30 constituents that met data-availability criteria over the window (Section 3.1). These firms span banking, basic resources, construction, real estate, consumer and IT/finance services (Appendix A), and collectively proxy the most actively traded segment of the market. Because a subset of EGX30 firms has government or government-linked shareholdings, while others are fully private and widely held, the ownership mix can shape devaluation pass-through to cash flows and investor clientele. A complete, verified ownership breakdown is outside our present scope; we therefore identify this as a limitation and a direction for future work that links state ownership, free float, and market capitalization to abnormal returns around devaluation announcements.

Egypt’s market features both domestic and foreign institutional investors; however, investor-type shares at the daily firm level are not observable for our window, precluding formal attribution. Likewise, while policy communication and exchange rate operations can shape expectations, disentangling such interventions from the devaluation signal itself requires additional data we do not possess; we treat this as a limitation.

2. Literature Review

Many studies have examined the relationship between exchange rates and stock prices for various developed countries, developing countries, and BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) due to the complex nature of the relationship between the exchange rate and stock returns, which varies depending on the period or country in which the study was conducted (Elroukh, 2024). Our conceptual pathway is that depreciation affects firm value through trade-exposure and cost channels: export-oriented firms gain competitiveness and potentially higher margins, whereas import-dependent firms face higher FX-denominated input costs and tighter working-capital constraints.

2.1. Results for Developed Economies

Empirical studies vary on the relationship between the exchange rate and stock returns. For example, a recent study by Sokhanvar et al. (2024) examined the relationship between exchange rates and stock market returns in four advanced economies (Germany, UK, Australia and Canada) before and during the war in Ukraine. The results indicated the positive effect of the GBP/USD on FTSE index returns before the war. Therefore, the relationship between exchange rates and stock returns is an empirical issue that can vary based on various factors, such as the country and sample period, so this relationship should be studied at the level of each country separately. Nusair and Olson (2022) examined the relationship between exchange rates and stock prices in the G7 countries (France, Italy, Germany, Canada, Japan, USA and the UK) using ARDL models. The results indicate that the foreign exchange and stock market affect each other in the short run and support the idea of the flow-oriented model vs. stock-oriented model. Additionally, the results indicate that an increase or decrease in stock prices has a long-run impact on exchange rates.

Ding (2021) focused on six developed countries and used monthly exchange rate and stock price data. The results indicated that it is likely that cash flows and hence the profitability of American companies improved with an increase in the value of the dollar, leading to an increase in stock prices, thus supporting the micro—based flow oriented. In a relatively more recent study by Xie et al. (2020) used a sample of four developed countries (the UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia) and six emerging economies, applying panel Granger non-causality tests. The results of this study indicated the existence of a two-way causality between the exchange rate and stock prices. Salisu and Ndako (2018) presented a new vision of the relationship between the exchange rate and stock prices in contrast to the finance literature, as it assumes that stock prices have a negative impact on exchange rates for a sample divided into countries in the eurozone, non-eurozone, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

2.2. Results for Emerging Economies

Managed exchange rates still represent the dominant regime in most emerging economies, and this may help explain the inconclusive findings in the financial literature (Aftab et al., 2021; Ilzetzki et al., 2019; Neokleous & Elmarzouky, 2025). Chang et al. (2024), investigated the relationship between exchange rates and stock market returns from 2020 to 2022 during the pandemic. The outcome emphasized a negative Granger causality between exchange rate and Taiwan stock market returns, but this effect is only for a single day. Umoru et al. (2023), studying the impact of changes in oil prices and exchange rates on stock returns in African oil-producing countries, using an autoregressive methodology, found that there are asymmetric and long-term effects for all countries under study. Fasanya and Akinwale (2022), this study showed the effect of exchange rates on stock returns for 10 different sectors in Nigeria. The result shows that the movement of the exchange rate affects sector returns differently, and that the financial services sector is the only sector that moves in an asymmetrical manner in the short and long term. A single model cannot be used for all sector returns because each sector responds differently to exchange rate shocks. Hung (2022), this study showed the dynamic relationship between exchange rates and stock returns of the five countries (Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania). The major finding is that the return and volatility effect from the stock return to the exchange rate is larger than the returns and volatility from the exchange rate to the stock return for CEE countries. Hashmi et al. (2022) found that the impact of exchange rate fluctuations on stock returns in Pakistan depends on whether the market is bullish or bearish. Aftab et al. (2021), using a DCC-GARCH model, found a significant negative varying association between exchange market pressure and stock market returns for all countries. Ahmed (2020), showed that the existence of spillover effects of exchange rate variations on stock prices and that currency depreciation tends to have a stronger influence on stock returns than currency appreciation. Dang et al. (2020) found a short-run relationship in Vietnam but not in the long run.

Zarei et al. (2019) showed a significant free exchange rate effect on Stock index returns in seven countries. Delgado et al. (2018) investigated the relationship between Currency devaluation and stock market Response in the Mexican economy for the period from 1992 to 2017, using Vector Autoregressive Model (VAR). These results reveal a negative impact of the Mexican exchange rate against the dollar on the Mexican stock market index. Bahar et al. (2018) showed that recurring devaluations negatively impact Venezuelan stock prices. Patro et al. (2014) investigated the relationship between the exchange rate and the stock market in 27 countries. Their results reveal that currency devaluation is expected in stock markets and therefore produces negative abnormal returns one year before the event, continues for 30 days after the event of the currency devaluation announcement, but one year after the currency devaluation, the abnormal returns become positive, and this devaluation usually has a negative impact on stock markets in developing countries.

From a comparative perspective, recurrent, sizable devaluations in Argentina and Turkey have made them frequent case studies for announcement effects in equity markets, with evidence of short-horizon negative abnormal returns around devaluation news and strong heterogeneity by trade exposure and FX balance-sheet positions. Our study extends this announcement-focus to Egypt, where the coexistence, until March 2024, of official and parallel exchange rates, followed by a move to a freer float, provides a distinct institutional setting for testing semi-strong efficiency at the firm level.

2.3. Results for BRICS Economies

Recent studies (Hussain et al., 2024) find that exchange rates and stock prices are connected, and that volatility increased during pandemic-related crises in BRICS countries. Mubaiwa and Fasanya (2024), in a study in South Africa, examined the effect of the USD/Rand exchange rate on sectoral stock returns. The study found that high fluctuations in exchange rates have a positive impact on stock returns, and therefore investors must have a keen awareness of movements in the stock markets and the exchange rate. Naresh et al. (2018), tried to identify the long-run spillover effect of the US dollar on major stock indices of BRICS nations based on the Generalized Method of Moments. This study found that an increase in the value of local currencies of Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa versus the dollar leads to an increase in the stock indices of each country. Sikhosana and Aye (2018), analyzed the asymmetric volatility spillovers between the exchange rate and stock returns in South Africa, based on US data. The results show that there is a bi-directional volatility spillover effect between the two markets in the short run. Dahir et al. (2018), this study analyzed the relationship between the exchange rate and stock returns of the BRICS countries. The study found a negative effect in India, a positive effect in Russia and Brazil, and a two-way relationship in South Africa.

The paper adds to the above financial literature by identifying the impact of the 2024 devaluation of the Egyptian currency on stock returns in the Egyptian stock market using an event-study method, which can help government policymakers and investors make more informed decisions. This study adopts the flow-oriented model as the theoretical foundation, in line with Dornbusch and Fischer (1980), given Egypt’s trade imbalances and the dominance of real economic shocks as key exchange rate drivers.

This study interprets the ARs using both the flow-oriented model and the portfolio rebalancing model. The flow-oriented model suggests that firms with export or foreign currency revenues will benefit from depreciation through increased competitiveness, while the portfolio rebalancing model posits that investor reactions may lead to capital reallocation across borders. These theoretical lenses guide our interpretation of firm-level reactions to the devaluation event.

While prior studies on currency devaluation, such as Delgado et al. (2018) on Mexico, Bahar et al. (2018) on Venezuela, and Hashmi et al. (2022) on Pakistan—have documented significant stock market responses, these analyses often rely on market-level indices or monthly data. In contrast, this study adopts a high-frequency, firm-level approach to examine the Egyptian stock market’s reaction to a single, clearly defined devaluation event. This design enhances internal validity and isolates the immediate response of stock prices to macroeconomic shocks, making a unique methodological and contextual contribution to literature.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample

The study population comprises all companies listed on the EGX30 index, which includes the 30 most liquid and actively traded firms in the Egyptian market. Two conditions were applied when selecting the final sample:

- Daily price data must be available for the entire study period, and each stock must have at least 100 trading days during the estimation window.

- Stocks must be actively traded, with regular transactions throughout the observation period.

Applying these criteria resulted in a final sample of 29 firms for which complete and reliable data were available. The full list of these firms is provided in Appendix A.

3.2. Data

The study data includes the daily closing prices of the study sample, in addition to the number of points of the EGX 30 index about the period from 13 September 2023 to 3 April 2024. Data for the EGX30 index and the daily closing prices for the study sample were obtained from www.egx.com.eg and www.investing.com (accessed on 30 December 2024) over the same period.

3.3. Research Method

3.3.1. Event Study Framework

Event studies (Fama et al., 1969) evaluate how quickly stock prices incorporate new information. We measure stock price reactions to the 6 March 2024 devaluation using abnormal returns (ARs), average abnormal returns (AAR), and cumulative average abnormal returns (CAAR), consistent with Rai and Pandey (2022).

The estimation window covers 9 December 2023–6 February 2024 (100 trading days), free from event contamination. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the events window spans 7 February 2024–3 April 2024, providing a [−20, +20] structure around the announcement (t = 0). These window lengths follow Brown and Warner (1985) and Strong (1992).

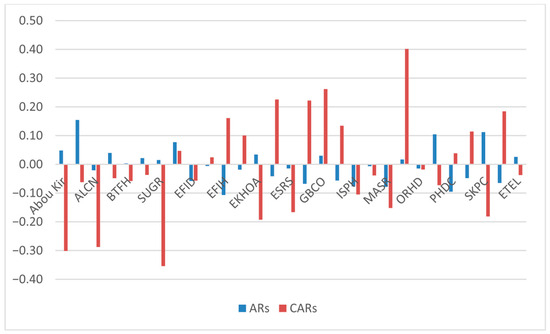

Figure 2.

Timeline of estimation and event windows for the March 2024 EGP devaluation event.

Figure 3.

Abnormal returns (ARs) & cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) of all stocks on announcement day. Abnormal returns (AR0) and cumulative abnormal returns (CAR0) for all firms on the devaluation announcement day (t = 0). AR0 represents the abnormal return on the announcement day; CAR0 represents the cumulative abnormal return through t = 0. Firms on the x-axis are ordered according to their numbering in Appendix A (firms 1–29), and the labels correspond to their trading tickers.

3.3.2. Expected, Abnormal and Cumulative Abnormal Returns

(a) Expected (Normal) Returns

The expected return for stock i on day t is estimated using the market model:

where

- = actual return on stock i at time t;

- = market index return;

- = OLS parameters estimated over the 100-day estimation window.

(b) Abnormal Returns (AR)

Abnormal returns capture the deviation between actual returns and expected returns in the absence of the event.

(c) Average Abnormal Return (AAR)

where N is the number of stocks in the sample (N = 29).

AARt = (1/N) × Σi=1N ARi,t

σ(ARt) = √[1/(N − 1) × Σi=1N (ARi,t − AARt)2]

σ(ARt) = √[1/(N − 1) × Σi=1N (ARi,t − AARt)2]

(d) Test Statistic for AAR (Corrected as per Rai & Pandey, 2022)

where

- = cross-sectional standard deviation of across firms;

- = t-test statistic.

(e) Cumulative Abnormal Returns (CAR)

CARi(τ1, τ2) = Σt=τ1→τ2 ARi,t

Note that the left-hand side depends only on , not on .

(f) Cumulative Average Abnormal Returns (CAAR)

(g) Test Statistic for CAAR

σ(CAR) = √[1/(N − 1) × Σi=1N (CARi − CAAR)2]

where

- = cross-sectional standard deviation of CARi across firms;

- The statistic tests whether CAAR differs from zero.

3.3.3. Hypothesis Testing

- 1.

- Null Hypothesis

There is no stock market reaction to the devaluation announcement.

- 2.

- Alternative Hypothesis

A non-zero CAAR indicates that the devaluation announcement influenced market returns.

4. Results

This study examines how stock returns respond to the 6 March 2024 devaluation of the EGP against foreign currencies, using an event-study method. We analyse three periods: 20 days before the event date, 20 days after the event date, and the full window from 20 days before to 20 days after the event, as shown in Figure 4. Using sectoral analysis, stock market responses vary significantly across different sectors. For the results of the pre-event period, there are no significant values for the CARs and CAAR of the groups, but significant losses of companies are SUGR (−35.44%) and Abou_Kir (−30.13%). While Delta Sugar Company (SUGR) relies on importing sugar to fill the gap in local production, Abu Qir Fertilizers Company (Abou_Kir) relies on importing gas. Despite its expansion in exports, the rise in gas exceeded the export process.

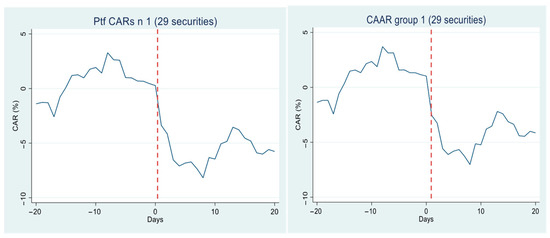

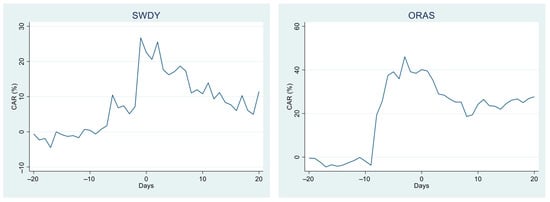

Figure 4.

CARs and CAARs of the devaluation announcement.

However, ORAS shows a significant positive CAAR of 40.15%, and SWDY a positive CAAR of 22.56%. We find that El Sewedy Company (SWDY) was positively affected by the purchase offer submitted by the Emirati company Electra Investment by 24.5%, while Orascom Company (ORAS) achieved a positive impact by the currency devaluation due to the presence of a large number of projects under implementation outside Egypt with dollar returns, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Event study analysis of devaluation announcement (6 March 2024).

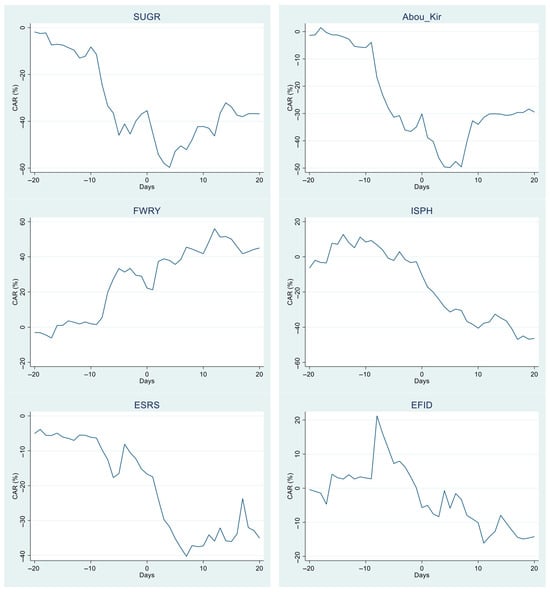

For the post-event period, CARs are not significantly negative for most firms, but the overall CAAR is significantly negative (−5.29%). However, the ISPH stock is significantly negative (−43.64%); this is due to Ibn Sina Company’s reliance on importing raw materials for medicine, in addition to paying part of the loans in foreign currency. The non-significant results for the overall observed period are the CAR equals to (−5.76%) and CAAR equals (−4.14%). The CAARs’ values are depicted in more detail in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

CARs-line for some firms during the event window.

As can be seen from the figure, stock prices began to decline from the event date onward and reached their trough around eight days after 6 March. According to the results of the overall period, we find that there are two companies that achieved significant positive results: FWRY with a CAAR of 45.02% and EFIH with a CAAR of 36.00%. This study found that e-finance for financial investments (EFIH) relies on domestic tourism and agriculture, both of which achieved high dollar returns from currency devaluation.

The heterogeneous stock reactions observed in our results can be interpreted through these theoretical frameworks. For instance, firms such as ORAS and FWRY show strong positive CARs, likely due to foreign income streams (flow-oriented model), whereas companies reliant on imported inputs like ISPH show significant declines, aligning with increased cost burdens and investor withdrawal (portfolio rebalancing model).

In general, stocks experienced significant losses before the event day, except for three companies that recorded positive returns: Orascom, Elsewedy, and Fawry. However, significant losses appeared after the event date, and the results showed a statistically significant negative CAR for Ibn Sina and Palm Hills. But, at the overall level, Fawry and e-finance for financial investments achieved significant positive results and confirmed the cumulative average abnormal returns results.

The results of this study revealed the inefficiency of the Egyptian stock market at the semi-strong level when the currency devaluation was announced due to the achievement of non-significant negative returns for most companies on the day of the currency devaluation announcement. The results also show non-significant negative returns, with the exception of some companies, before and after the announcement. Our analysis is consistent with the Flow-oriented model suggested by Dornbusch and Fischer (1980) and also with previous studies (Chang et al., 2024; Elgharib, 2023; Hashmi et al., 2022; Aftab et al., 2021; Delgado et al., 2018; Bahar et al., 2018; Dahir et al., 2018).

These results can be explained by the fact that, prior to the devaluation, stock prices were already reflecting the unofficial or parallel market exchange rate of the EGP. In addition, the Egyptian market expected a partial devaluation of the currency due to the presence of prior signals, such as difficult economic conditions and a decline in foreign reserves, which led to an upward trend in the stock market, which is consistent with the study (Hashmi et al., 2022).

After the devaluation, the official exchange rate converged to the unofficial market rate, and stock prices began to decline gradually because many stocks had already peaked and investors started to realize profits. Hence, there have been no significant increases in prices since that date or after. In addition, the continued decline in stock prices after the devaluation can be interpreted as institutional investors and funds taking profits after the pre-devaluation rally. The 600-basis-point increase in interest rates also made interest-bearing instruments a strong competitor to Egyptian stocks.

Thus, the consecutive rises in stock prices before the devaluation likely reflected investors’ prior information about the approaching devaluation of the EGP and their belief that the currency was overvalued relative to informal market prices that had already exceeded 70 EGP per USD. This limit is explained by the decline in stock prices since the date of the devaluation of the pound and after this date.

Additional Analyses and Robustness

To validate the baseline event-study results, we conducted several supplementary tests:

- Short-window analysis: re-estimating AAR and CAAR over [−5, +5] and [−10, +10] day windows.

- Alternative benchmarks: computing market-adjusted and three-factor-adjusted abnormal returns using available factor data.

- Outlier robustness: Winsorizing abnormal returns at the 1st and 99th percentiles and applying sign and median tests.

The sign and direction of our findings remain unchanged, confirming that the limited abnormal responses are not model-specific.

5. Conclusions

This study offers empirical evidence on how the Egyptian stock market responded to the 2024 devaluation of the Egyptian Pound (EGP), with a specific focus on evaluating market efficiency at the semi-strong form level. Using an event study methodology applied to EGX30 firms, the study assessed abnormal returns across defined estimation and event windows to capture the immediate impact of the currency devaluation. The findings reveal weak evidence of semi-strong efficiency, with mostly statistically insignificant abnormal returns on the announcement day, suggesting that the market did not fully and promptly reflect new macroeconomic information.

Theoretically, this study builds on the flow-oriented and portfolio rebalancing models (Dornbusch & Fischer, 1980; Hau & Rey, 2004; Ding, 2021; Xie et al., 2020) and reinforces their relevance in explaining investor reactions to currency movements in emerging markets. The results support the notion that exchange rate fluctuations—especially in contexts of policy-driven devaluation—significantly influence investor confidence, firm valuation, and capital flows. By examining the event in a market exposed to multiple structural shocks, this research extends understanding of the mechanisms through which currency risk affects market efficiency, particularly under central bank-led exchange rate realignments.

Practically, the findings hold important implications for policymakers, market regulators, and investors. The observed asymmetry in abnormal returns across firms underscores the importance of foreign revenue exposure and import dependency in mediating market responses. Policymakers are encouraged to facilitate greater international diversification among Egyptian firms, particularly in light of repeated devaluation cycles and declining foreign currency revenues from sources like the Suez Canal, tourism, and remittances. These measures could help firms hedge against currency volatility and contribute to broader financial stability. Additionally, the study highlights the need for improved transparency and timely access to information in the Egyptian capital market to prevent informational asymmetries that allow certain investors to earn abnormal profits.

The findings also raise broader concerns about the effectiveness of exchange rate manipulation as a tool for influencing stock prices. In environments where unofficial exchange rates exist (e.g., in automotive, gold, and futures markets), discrepancies between official and real market conditions can distort investor behavior. Therefore, efforts to achieve a unified and transparent currency regime are critical to restoring investor trust and improving the informational efficiency of the Egyptian stock market.

In addition, the study calls attention to the ongoing shift in public versus private ownership in Egypt. Given the government’s intention to restructure and privatize state-owned enterprises, stable macroeconomic signals, including a transparent exchange rate regime, will be essential for attracting foreign direct investment and ensuring the resilience of capital markets. By promoting a more predictable currency environment, the state can help foster a more efficient, investor-friendly market structure. Overall, we find limited evidence consistent with semi-strong efficiency: for most firms, announcement-day abnormal returns are statistically insignificant across baseline and robustness checks.

Despite its contributions, the study has limitations that provide opportunities for future research. First, it focuses on short-term market reactions, thereby excluding the long-run impacts of currency devaluation on stock prices, which may evolve over several months or years. Second, the analysis is restricted to a single event and does not control for other internal or external shocks—such as dividend announcements, macroeconomic news, or geopolitical developments—that could have influenced stock returns during the same period. Third, we do not quantify firm-level market capitalization, free float, or state-ownership flags for all issuers. Incorporating these characteristics would allow testing whether ownership structure conditions announcement effects. We do not estimate a reverse-causality model between stock returns and the exchange rate because suitable intraday or factor-purged data are unavailable; our identification instead relies on the exogenous timing of the March 2024 policy announcement. Finally, country-level consequences for inward FDI and portfolio flows are not evaluated here; our high-frequency design isolates immediate price reactions (Lunawat et al., 2025; Elmarzouky et al., 2025; Karim et al., 2025; Mintah et al., 2025). Future work could link monthly/quarterly FDI and net equity flows to post-announcement return dynamics.

To address these limitations, future research could extend the event window and include multiple devaluation episodes to capture cumulative effects. Comparative studies across MENA countries could also offer cross-border insights into how different institutional and regulatory environments mediate the stock market impact of currency devaluation. Additionally, incorporating firm-level characteristics such as export ratios, FX debt levels, and ownership structures could help uncover transmission mechanisms and investor expectations in greater depth. Finally, future research could employ mixed methods, combining event study analysis with interviews or surveys of market participants, to provide more contextualized insights into investor behaviour under exchange rate volatility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.A.E.; methodology, W.A.E.; validation, W.A.E.; formal analysis, W.A.E.; investigation, M.E. and D.S.; resources, M.E.; data curation, W.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, W.A.E.; writing—review and editing, M.E. and D.S.; visualization, W.A.E.; supervision, M.E. and D.S.; project administration, D.S. and M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Firm Names

| N. | Company Name | Reuters Code | ISIN | Sector |

| 1 | Abou Kir Fertilizers | ABUK.CA | EGS512O1C012 | Basic Resources |

| 2 | Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank-Egypt | ADIB.CA | EGS38191C010 | Trade Banks |

| 3 | Alexandria Containers and goods | ALCN.CA | EGS42111C012 | Shipping & Transportation Services |

| 4 | Alexandria Mineral Oils Company | AMOC.CA | EGS380P1C010 | Energy & Support Services |

| 5 | Beltone Holding | BTFH.CA | EGS60121C018 | Non-bank financial services |

| 6 | Commercial International Bank-Egypt | COMI.CA | EGS30201C015 | Banks |

| 7 | Delta Sugar | SUGR.CA | EGS3G0Z1C014 | Food, Beverages and Tobacco |

| 8 | Eastern Company | EAST.CA | EGS37091C013 | Food, Beverages and Tobacco |

| 9 | Edita Food Industries S.A. E | EFID.CA | EGS69082C013 | Food, Beverages and Tobacco |

| 10 | EFG Holding | HRHO.CA | EGS69081C023 | Non-bank financial services |

| 11 | E-finance For Digital & Financial Investments | EFIH.CA | EGS73541C012 | IT, Media & Communication Services |

| 12 | Egyptian International Pharmaceuticals | PHAR.CA | EGS38081C013 | Health Care & Pharmaceuticals |

| 13 | Egyptian Kuwaiti Holding-EGP | EKHOA.CA | EGS33041C012 | Non-bank financial services |

| 14 | Elswedy Electric | SWDY.CA | EGS95001C011 | Industrial Goods, Services and Automobiles |

| 15 | Ezz Steel | ESRS.CA | EGS70321C012 | Basic Resources |

| 16 | Fawry For Banking Technology | FWRY.CA | EGS743O1C013 | IT, Media & Communication Services |

| 17 | GB Corp | GBCO.CA | EGS305I1C011 | Industrial Goods, Services and Automobiles |

| 18 | Heliopolis Housing | HELI.CA | EGS655L1C012 | Real Estate |

| 19 | Ibnsina Pharma | ISPH.CA | EGS691G1C015 | Health Care & Pharmaceuticals |

| 20 | Juhayna Food Industries | JUFO.CA | EGS30901C010 | Food, Beverages and Tobacco |

| 21 | Madinet Masr For Housing and Development | MASR.CA | EGS673T1C012 | Real Estate |

| 22 | Misr Fertilizers Production Company (MOPCO) | MFPC.CA | EGS3C251C013 | Basic Resources |

| 23 | Orascom Construction PLC | ORAS.CA | EGS380S1C017 | Contracting & Construction Engineering |

| 24 | Orascom Development Egypt | ORHD.CA | EGS745L1C014 | Real Estate |

| 25 | Oriental Weavers | ORWE.CA | EGS69101C011 | Textile & Durables |

| 26 | Palm Hills Development Company | PHDC.CA | EGS691S1C011 | Real Estate |

| 27 | QALA For Financial Investments | CCAP.CA | EGS65571C019 | Non-bank financial services |

| 28 | Sidi Kerir Petrochemicals—SIDPEC | SKPC.CA | EGS65591C017 | Basic Resources |

| 29 | T M G Holding | TMGH.CA | EGS39061C014 | Real Estate |

| 30 | Telecom Egypt | ETEL.CA | EGS60111C019 | IT, Media & Communication Services |

References

- Aftab, M., Ali, A., & Hegerty, S. W. (2021). Foreign exchange market pressure and stock market dynamics in emerging Asia. International Economics and Economic Policy, 18, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W. M. (2020). Asymmetric impact of exchange rate changes on stock returns: Evidence of two de facto regimes. Review of Accounting and Finance, 19(2), 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, D., Molina, A., & Santos, M. A. (2018). Fool’s gold: The impact of Venezuelan devaluations in multinational stock prices. Economía, 19(1), 93–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. J., & Warner, J. B. (1985). Using daily stock returns: The case of event studies. Journal of Financial Economics, 14(1), 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. W., Chang, T., & Wang, M. C. (2024). Revisit the impact of exchange rate on stock market returns during the pandemic period. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 70, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chortareas, G., Cipollini, A., & Eissa, M. A. (2012). Switching to floating exchange rates, devaluations, and stock returns in MENA countries. International Review of Financial Analysis, 21, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahir, A. M., Mahat, F., Ab Razak, N. H., & Bany-Ariffin, A. N. (2018). Revisiting the dynamic relationship between exchange rates and stock prices in BRICS countries: A wavelet analysis. Borsa Istanbul Review, 18(2), 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V. C., Le, T. L., Nguyen, Q. K., & Tran, D. Q. (2020). Linkage between exchange rate and stock prices: Evidence from Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(12), 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, N. A. B., Delgado, E. B., & Saucedo, E. (2018). The relationship between oil prices, the stock market and the exchange rate: Evidence from Mexico. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 45, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L. (2021). Conditional correlation between exchange rates and stock prices. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 80, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornbusch, R., & Fischer, S. (1980). Exchange rates and the current account. The American Economic Review, 70(5), 960–971. [Google Scholar]

- Elgharib, W. A. (2023). The effect of the COVID-19 announcement on stock returns: Evidence from Egypt. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 14(3), 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmarzouky, M., Moussa, T., & Allam, A. (2025). Cybersecurity disclosure: Board commitment and regulatory impact in the United Kingdom. The International Journal of Accounting. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elroukh, A. W. (2024). The reaction of the Egyptian stock market to recurring devaluations: An event study approach. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 15(3), 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., Fisher, L., Jensen, M. C., & Roll, R. (1969). The adjustment of stock prices to new information. International Economic Review, 10(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasanya, I. O., & Akinwale, O. A. (2022). Exchange rate shocks and sectoral stock returns in Nigeria: Do asymmetry and structural breaks matter? Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2045719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, S. M., Chang, B. H., Huang, L., & Uche, E. (2022). Revisiting the relationship between oil prices, exchange rate, and stock prices: An application of quantile ARDL model. Resources Policy, 75, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, H., & Rey, H. (2004). Can portfolio rebalancing explain the dynamics of equity returns, equity flows, and exchange rates? American Economic Review, 94(2), 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, N. T. (2022). Spillover effects between stock prices and exchange rates for the central and eastern European countries. Global Business Review, 23(2), 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M., Bashir, U., & Rehman, R. U. (2024). Exchange rate and stock prices volatility connectedness and spillover during pandemic induced-crises: Evidence from BRICS countries. Asia-Pacific Financial Markets, 31(1), 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilzetzki, E., Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2019). Exchange arrangements entering the twenty-first century: Which anchor will hold? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(2), 599–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, E., Elmarzouky, M., & Shohaieb, D. (2025). Green revenue generation and sales contribution: Are consumers willing to bear the cost of sustainability? Business Strategy and the Environment. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunawat, R. M., Elmarzouky, M., & Shohaieb, D. (2025). Integrating Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors into the investment returns of American companies. Sustainability, 17(19), 8522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintah, E. O., Elmarzouky, M., & Shohaieb, D. (2025). Examining airlines’ environmental and social disclosure: Does board gender diversity matter? Business Strategy and the Environment. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubaiwa, D., & Fasanya, I. (2024). Quantile dependencies between exchange rate volatility and sectoral stock returns in South Africa. Investment Analysts Journal, 53(2), 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, G., Vasudevan, G., Mahalakshmi, S., & Thiyagarajan, S. (2018). Spillover effect of US dollar on the stock indices of BRICS. Research in International Business and Finance, 44, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neokleous, C. I., & Elmarzouky, M. (2025). Strategic sustainability reporting, impression management and board gender diversity: Evidence from luxury fashion industry. Business Strategy and the Environment. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusair, S. A., & Olson, D. (2022). Dynamic relationship between exchange rates and stock prices for the G7 countries: A nonlinear ARDL approach. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 78, 101541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, D. K., Wald, J. K., & Wu, Y. (2014). Currency devaluation and stock market response: An empirical analysis. Journal of International Money and Finance, 40, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V. K., & Pandey, D. K. (2022). Does privatization of public sector banks affect stock prices? An event study approach on the Indian banking sector stocks. Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 7(1), 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, A. A., & Ndako, U. B. (2018). Modelling stock price–exchange rate nexus in OECD countries: A new perspective. Economic Modelling, 74, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikhosana, A., & Aye, G. C. (2018). Asymmetric volatility transmission between the real exchange rate and stock returns in South Africa. Economic Analysis and Policy, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokhanvar, A., Çiftçioğlu, S., & Hammoudeh, S. (2024). Comparative analysis of the exchange rates-stock returns nexus in commodity-exporters and-importers before and during the war in Ukraine. Research in International Business and Finance, 67, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, N. (1992). Modelling abnormal returns: A review article. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 19(4), 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoru, D., Effiong, S. E., Umar, S. S., Okpara, E., Ugbaka, M. A., Otu, C. A., Ofie, F. E., Tizhe, A. N., & Ekeoba, A. A. (2023). Reactions of stock returns to asymmetric changes in exchange rates and oil prices. Corporate Governance and Organizational Behavior Review, 7(3), 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z., Chen, S. W., & Wu, A. C. (2020). The foreign exchange and stock market nexus: New international evidence. International Review of Economics & Finance, 67, 240–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A., Ariff, M., & Bhatti, M. I. (2019). The impact of exchange rates on stock market returns: New evidence from seven free-floating currencies. The European Journal of Finance, 25(14), 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).