The Rise of the Chaebol: A Bibliometric Analysis of Business Groups in South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Bibliometric Networks

2.2. Data Collection and Previous Studies

2.3. Data Preparation and Software

3. Overview of Chaebol Groups

3.1. Historical Background and Comparison to Keiretsu Networks

3.2. Internal Markets and Corporate Governance

3.3. Asian Financial Crisis and Market Liberalization

3.4. The Political Power of the Largest Chaebol Groups

4. Results of Bibliometric Analysis

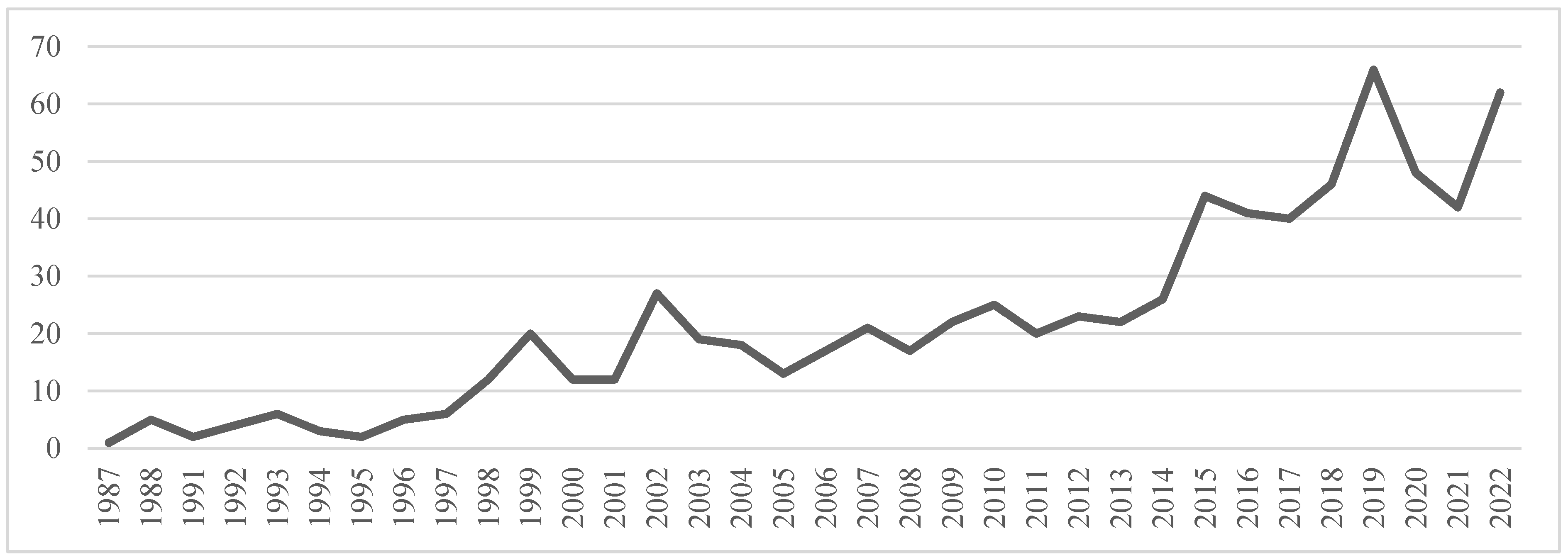

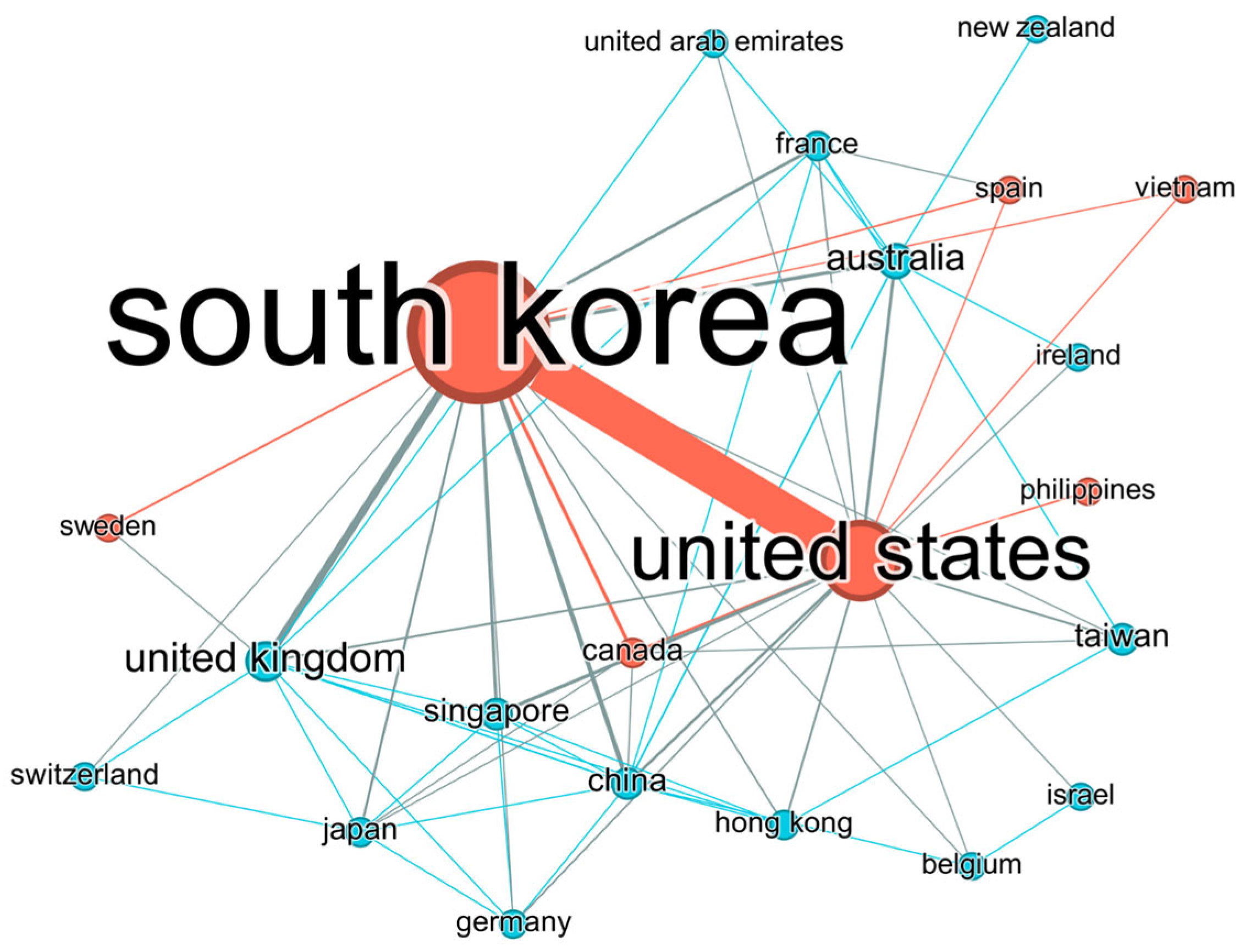

4.1. Prolific Journals, Institutions, and Scientific Collaboration

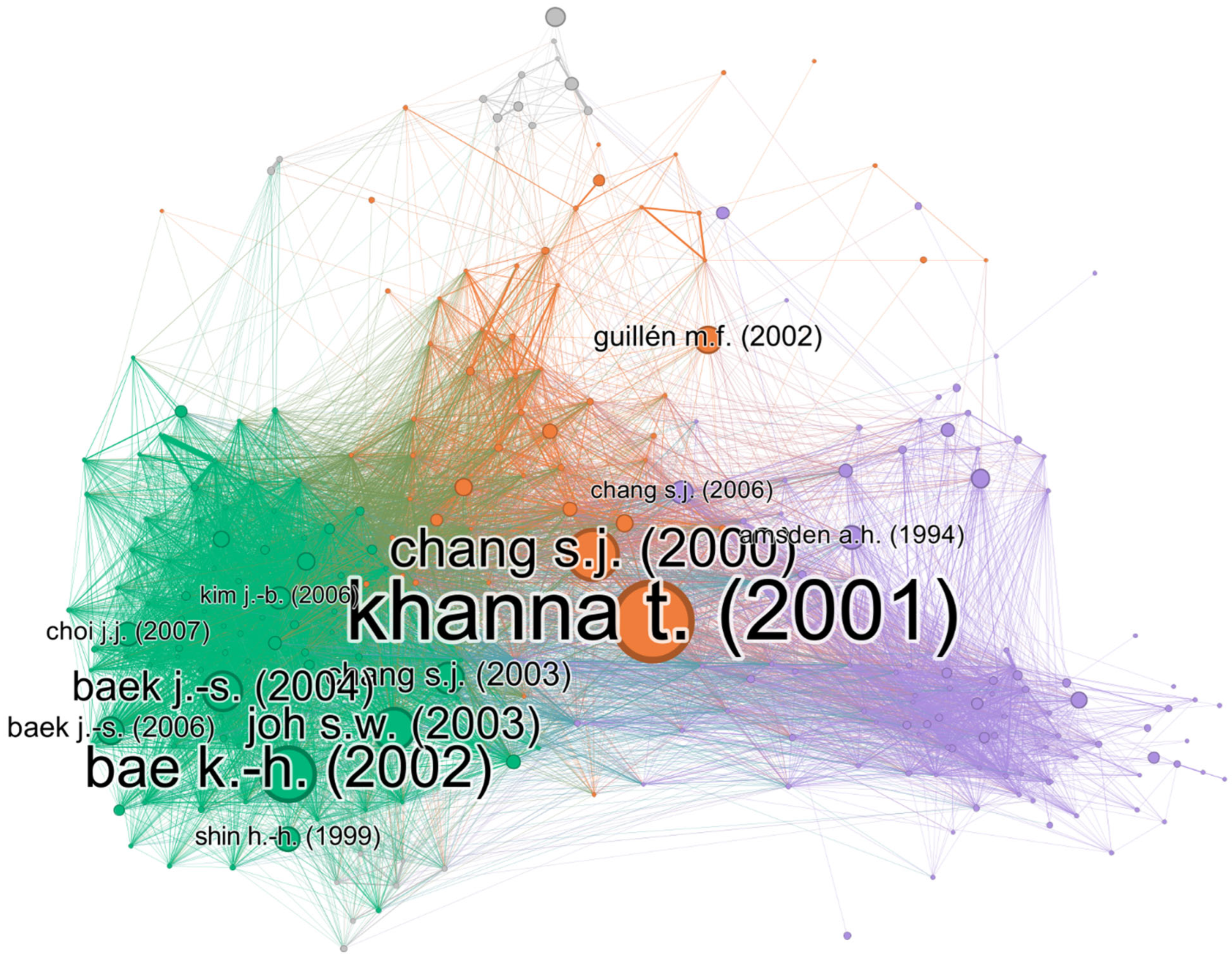

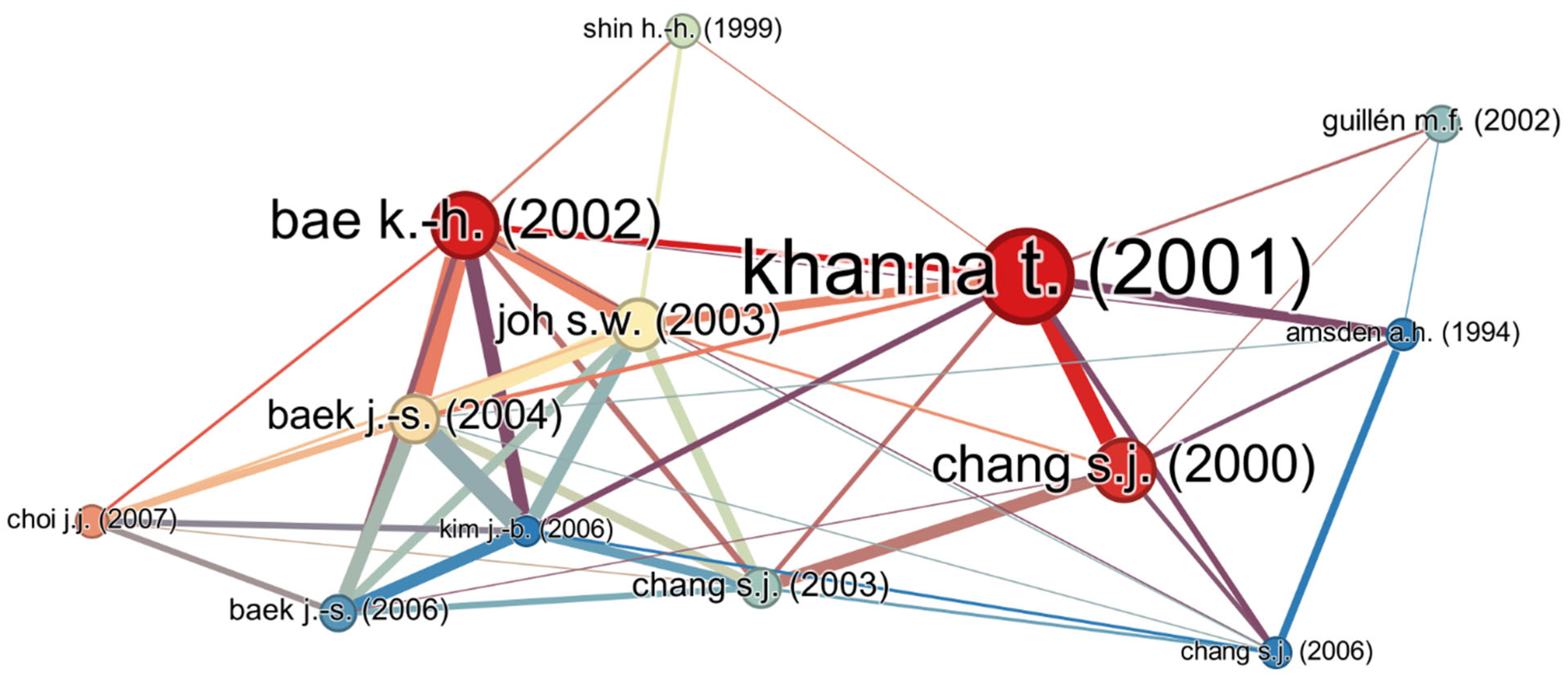

4.2. Bibliographic Coupling Network and Influential Articles

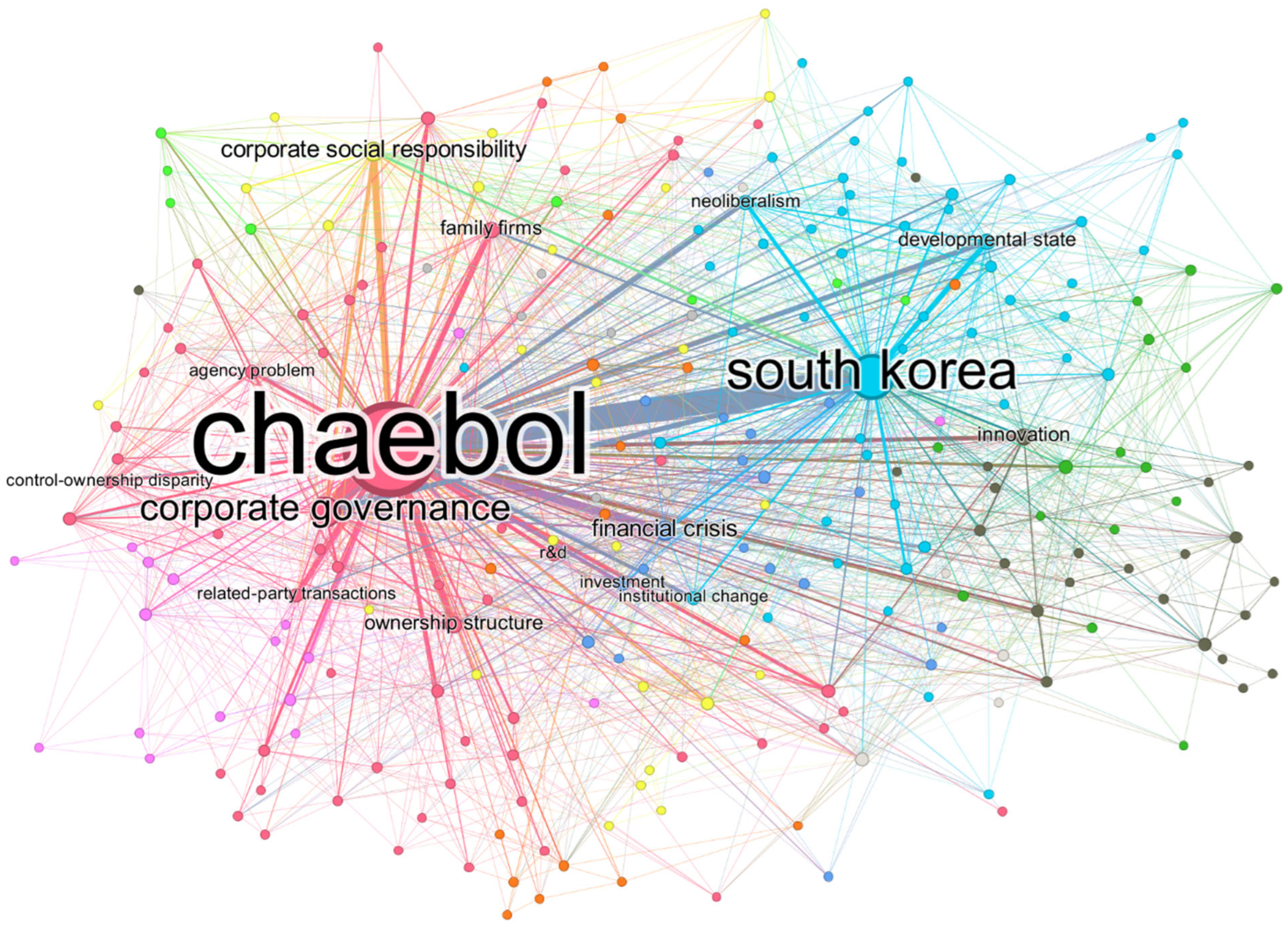

4.3. Keyword Co-Occurrence Network and Main Themes of Research

5. Implications

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbasi, A., Hossain, L., & Leydesdorff, L. (2012). Betweenness centrality as a driver of preferential attachment in the evolution of research collaboration networks. Journal of Informetrics, 6(3), 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, C., Turnbull, C., Zhang, Y., & Skousen, C. J. (2010). The relationship between South Korean chaebols and fraud. Management Research Review, 33(3), 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fadhat, F., & Choi, J.-W. (2023). Insights from the 2022 South Korean presidential election: Polarisation, fractured politics, inequality, and constraints on power. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 53, 724–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, H., Kim, C.-S., & Kim, H. B. (2015). Internal capital markets in business groups: Evidence from the Asian financial crisis. The Journal of Finance, 70(6), 2539–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, H., Park, S. Y., Subrahmanyam, M. G., & Wolfenzon, D. (2011). The structure and formation of business groups: Evidence from Korean chaebols. Journal of Financial Economics, 99(2), 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsden, A. H., & Hikino, T. (1994). Project execution capability, organizational know-how and conglomerate corporate growth in late industrialization. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3(1), 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, M., Patrick, H., & Sheard, P. (1994). The Japanese main bank system: An introductory overview. In M. Aoki, & H. Patrick (Eds.), The Japanese main bank system: Its relevance for developing and transforming economies (pp. 1–50). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, G. S., Cheon, Y. S., & Kang, J.-K. (2008). Intragroup propping: Evidence from the stock-price effects of earnings announcements by Korean business groups. Review of Financial Studies, 21(5), 2015–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.-H., Kang, J.-K., & Kim, J.-M. (2002). Tunneling or value added? Evidence from mergers by Korean business groups. The Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2695–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.-S., Kang, J.-K., & Lee, I. (2006). Business groups and tunneling: Evidence from private securities offerings by Korean chaebols. The Journal of Finance, 61(5), 2415–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.-S., Kang, J.-K., & Suh Park, K. (2004). Corporate governance and firm value: Evidence from the Korean financial crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 71(2), 265–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabási, A. L., Jeong, H., Néda, Z., Ravasz, E., Schubert, A., & Vicsek, T. (2002). Evolution of the social network of scientific collaborations. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 311(3–4), 590–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 3(1), 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, D., & Rosen, R. (1978). Studies in scientific collaboration: Part I. The professional origins of scientific co-authorship. Scientometrics, 1(1), 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008(10), P10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P. J. (2004). Asian network firms: An analytical framework. Asia Pacific Business Review, 10(3–4), 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, H.-Y., Choi, S., Hwang, L.-S., & Kim, R. G. (2013). Business group affiliation, ownership structure, and the cost of debt. Journal of Corporate Finance, 23, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, H.-Y., Hwang, L.-S., & Lee, W.-J. (2011). How does ownership concentration exacerbate information asymmetry among equity investors? Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 19(5), 511–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T. L., & Keys, P. Y. (2002). Corporate governance in South Korea: The chaebol experience. Journal of Corporate Finance, 8(4), 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J., Cho, Y. J., & Shin, H.-H. (2007). The change in corporate transparency of Korean firms after the Asian financial crisis: An analysis using analysts’ forecast data. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(6), 1144–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J., & Shin, H.-H. (2007). Family ownership and performance in Korean conglomerates. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 15(4), 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. J. (2003). Ownership structure, expropriation, and performance of group-affiliated companies in Korea. Academy of Management Journal, 46(2), 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. J., Chung, C.-N., & Mahmood, I. P. (2006). When and how does business group affiliation promote firm innovation? A tale of two emerging economies. Organization Science, 17(5), 527–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. J., & Hong, J. (2000). Economic performance of group-affiliated companies in Korea: Intragroup-resource sharing and internal business transactions. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Zhang, Y., & Fu, X. (2019). International research collaboration: An emerging domain of innovation studies? Research Policy, 48(1), 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, J. (2003). The ‘big deals’ and Hynix semiconductor: State–business relations in post-crisis Korea. Asia Pacific Business Review, 10(2), 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizema, A., & Kim, J. (2010). Outside directors on Korean boards: Governance and institutions. Journal of Management Studies, 47(1), 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J., Yang, D., Baek, K., & Bu, Y. (2025). Market competition, downward-sticky pay, and stock returns: Lessons from South Korea. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-H., Yu, G.-C., Joo, M.-K., & Rowley, C. (2014). Changing corporate culture over time in South Korea. Asia Pacific Business Review, 20(1), 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, H., & Lee, D. H. (2017). The structure and change of the research collaboration network in Korea (2000–2011): Network analysis of joint patents. Scientometrics, 111(2), 917–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S., & Pattnaik, C. (2007). The transformation of Korean business groups after the Asian crisis. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 37(2), 232–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B. B., Lee, D., & Park, Y. (2013). Corporate social responsibility, corporate governance and earnings quality: Evidence from Korea: CSR, corporate governance and earnings quality. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 21(5), 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D., Choi, P. M. S., Choi, J. H., & Chung, C. Y. (2020). Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility: Evidence from the role of the largest institutional blockholders in the Korean market. Sustainability, 12(4), 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. J., Park, S. W., & Yoo, S. S. (2007). The value of outside directors: Evidence from corporate governance reform in Korea. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 42(4), 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. K., Han, S. H., & Kwon, Y. (2019). CSR activities and internal capital markets: Evidence from Korean business groups. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 55, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choung, J.-Y., & Hwang, H.-R. (2013). The evolutionary patterns of knowledge production in Korea. Scientometrics, 94(2), 629–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.-M., & Shin, S.-Y. (2018). Does analyst coverage enhance firms’ corporate social performance? Evidence from Korea. Sustainability, 10(7), 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C. Y., Kim, D., & Lee, J. (2020). Do institutional investors improve corporate governance quality? Evidence from the blockholdings of the Korean National Pension Service. Global Economic Review, 49(4), 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C. Y., Kim, H., & Wang, K. (2022). Do domestic or foreign institutional investors matter? The case of firm information asymmetry in Korea. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 72, 101727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytis, E., Eriotis, N., & Mitroulia, M. (2024). ESG in business research: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(10), 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R. H. (1960). The problem of social cost. The Journal of Law and Economics, 3(1), 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, B., & dela Rama, M. (2016). Understanding the rise and decline of shareholder activism in South Korea: The explanatory advantages of the theory of modes of exchange. Asia Pacific Business Review, 22(3), 468–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducret, R., & Isakov, D. (2020). The Korea discount and chaebols. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 63, 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J. H. (1998). American investment in British manufacturing industry (2nd ed.). Routledge. (Original work published 1958). [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. (2008). Multinational enterprises and the global economy (2nd ed.). Edward Elgar. (Original work published 1993). [Google Scholar]

- Elsevier. (2023). Scopus database. Available online: https://www.scopus.com (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Fernandes, A. J., & Ferreira, J. J. (2022). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and networks: A literature review and research agenda. Review of Managerial Science, 16(1), 189–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, R., & Kang, J. W. (2022). Transforming Korean business? Foreign acquisition, governance and management after the 1997 Asian crisis. Asia Pacific Business Review, 28(1), 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, S. (2018). Impacts of Japan’s negative interest rate policy on Asian financial markets. Pacific Economic Review, 23(1), 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, E. (1955). Citation indexes for science: A new dimension in documentation through association of ideas. Science, 122(3159), 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, J. L., & Kim, W. Y. (2013). Are foreign investors really beneficial? Evidence from South Korea. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 25, 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A. S., Pattnaik, C., Singh, D., & Lee, J. Y. (2019). Internalization advantage and subsidiary performance: The role of business group affiliation and host country characteristics. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(8), 1253–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazni, A., & Didegah, F. (2011). Investigating different types of research collaboration and citation impact: A case study of Harvard University’s publications. Scientometrics, 87(2), 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, J., & Choi, Y.-J. (2014). The chaebol and the US military—Industrial complex: Cold war geopolitical economy and South Korean industrialization. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 46(5), 1160–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glänzel, W. (2001). National characteristics in international scientific co-authorship relations. Scientometrics, 51(1), 69–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glänzel, W., & Schubert, A. (2001). Double effort = Double impact? A critical view at international co-authorship in chemistry. Scientometrics, 50(2), 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glänzel, W., & Schubert, A. (2005). Analysing scientific networks through co-authorship. In H. F. Moed, W. Glänzel, & U. Schmoch (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative science and technology research (pp. 257–276). Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, M. F. (2002). Structural inertia, imitation, and foreign expansion: South Korean firms and business groups in China, 1987-95. Academy of Management Journal, 45(3), 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.-C., & Lee, W. H. (2007). The politics of economic reform in South Korea: Crony capitalism after ten years. Asian Survey, 47(6), 894–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggard, S. (2018). Developmental states. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggard, S., Kim, B.-K., & Moon, C. (1991). The transition to export-led growth in South Korea: 1954–1966. The Journal of Asian Studies, 50(4), 850–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggard, S., & Mo, J. (2000). The political economy of the Korean financial crisis. Review of International Political Economy, 7(2), 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggard, S., & Moon, C. (1990). Institutions and economic policy: Theory and a Korean case study. World Politics, 42(2), 210–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-S., & Lee, J.-W. (2020). Demographic change, human capital, and economic growth in Korea. Japan and the World Economy, 53, 100984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. (2022). Elite polarization in South Korea: Evidence from a natural language processing model. Journal of East Asian Studies, 22(1), 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobday, M., Rush, H., & Bessant, J. (2004). Approaching the innovation frontier in Korea: The transition phase to leadership. Research Policy, 33(10), 1433–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, K., & Park, H. W. (2018). An altmetric investigation of the online visibility of South Korea-based scientific journals. Scientometrics, 117(1), 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundt, D. (2014). Economic crisis in Korea and the degraded developmental state. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 68(5), 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymer, S. H. (1960). The international operations of national firms, a study of direct foreign investment [Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology]. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/27375 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Jang, S. S., Ko, H., Chung, Y., & Woo, C. (2019). CSR, social ties and firm performance. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 19(6), 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.-Y., & Masson, R. T. (1990). Market structure, entry, and performance in Korea. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72(3), 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S. W. (2016). Types of foreign networks and internationalization performance of Korean SMEs. Multinational Business Review, 24(1), 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S. W., Jin, B. E., & Jung, S. (2019). The temporal effects of social and business networks on international performance of South Korean SMEs. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 31(4), 1042–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Ritchie, B. W., & Benckendorff, P. (2019). Bibliometric visualisation: An application in tourism crisis and disaster management research. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(16), 1925–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y. (2020). Exclusionary effects of internal transactions of large business groups. Global Economic Review, 49(3), 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, D. Y., Oh, F. D., & Yoo, H. (2019). Foreign ownership and firm innovation: Evidence from Korea. Global Economic Review, 48(3), 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joh, S. W. (2003). Corporate governance and firm profitability: Evidence from Korea before the economic crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 68(2), 287–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B.-K., & Lee, I. (2017). Workplace happiness: Work engagement, career satisfaction, and subjective well-being. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 5(2), 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B.-K., Lim, D. H., & Kim, S. (2016). Enhancing work engagement: The roles of psychological capital, authentic leadership, and work empowerment. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 37(8), 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, I., Sheldon, P., & Rhee, J. (2010). Business groups and regulatory institutions: Korea’s chaebols, cross-company shareholding and the East Asian crisis. Asian Business & Management, 9(4), 499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, I.-W., Kim, K.-I., & Rowley, C. (2019). Organizational culture and the tolerance of corruption: The case of South Korea. Asia Pacific Business Review, 25(4), 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B., Lee, D., Rhee, S. G., & Shin, I. (2019). Business group affiliation, internal labor markets, external capital markets, and labor investment efficiency. Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies, 48(1), 65–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-K., & Choi, J. Y. (2022). Choice and allocation characteristics of faculty time in Korea: Effects of tenure, research performance, and external shock. Scientometrics, 127(5), 2847–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. C., Anderson, R. M., Eom, K. S., & Kang, S. K. (2017). Controlling shareholders’ value, long-run firm value and short-term performance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 43, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-K., Lee, I., & Na, H. S. (2010). Economic shock, owner-manager incentives, and corporate restructuring: Evidence from the financial crisis in Korea. Journal of Corporate Finance, 16(3), 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S., Chung, C. Y., & Kim, D.-S. (2019). The effect of institutional blockholders’ short-termism on firm innovation: Evidence from the Korean market. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 57, 101188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S. J., & Lee, H. S. (2007). The determinants of location choice of South Korean FDI in China. Japan and the World Economy, 19(4), 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T., Kim, W., & Lee, J. H. (2007). Executive compensation, firm performance, and Chaebols in Korea: Evidence from new panel data. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 15(1), 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, M. M. (1963a). An experimental study of bibliographic coupling between technical papers. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 9(1), 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, M. M. (1963b). Bibliographic coupling between scientific papers. American Documentation, 14(1), 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KFTC. (2022). Annual report 2022. Available online: https://www.ftc.go.kr/eng/selectBbsNttList.do?bordCd=822&key=564 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- KFTC. (2025a). Annual report 2025. Available online: https://www.ftc.go.kr/eng/selectBbsNttList.do?bordCd=822&key=564 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- KFTC. (2025b). History. Available online: https://www.ftc.go.kr/eng/contents.do?key=538 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- KFTC. (2025c). What we do. Available online: https://www.ftc.go.kr/eng/contents.do?key=535 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Khanna, T., & Rivkin, J. W. (2001). Estimating the performance effects of business groups in emerging markets. Strategic Management Journal, 22(1), 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, T., & Yafeh, Y. (2007). Business groups in emerging markets: Paragons or parasites? Journal of Economic Literature, 45(2), 331–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A., & Lee, Y. (2018). Family firms and corporate social performance: Evidence from Korean firms. Asia Pacific Business Review, 24(5), 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B., & Lee, I. (2003). Agency problems and performance of Korean companies during the Asian financial crisis: Chaebol vs. non-chaebol firms. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 11(3), 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-K., & Im, H.-B. (2001). ‘Crony capitalism’ in South Korea, Thailand and Taiwan: Myth and reality. Journal of East Asian Studies, 1(1), 5–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C., Park, J.-H., Kim, J., & Lee, Y. (2022). The shadow of a departing CEO: Outsider succession and strategic change in a business group. Asia Pacific Business Review, 28(1), 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. (2006). The impact of family ownership and capital structures on productivity performance of Korean manufacturing firms: Corporate governance and the “chaebol problem”. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 20(2), 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. M., & Oh, J. (2012). Determinants of foreign aid: The case of South Korea. Journal of East Asian Studies, 12(2), 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., & Han, S. H. (2018). Compensation structure of family business groups. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 51, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Heshmati, A., & Aoun, D. (2006). Dynamics of capital structure: The case of Korean listed manufacturing companies. Asian Economic Journal, 20(3), 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Hoskisson, R. E., Tihanyi, L., & Hong, J. (2004). The evolution and restructuring of diversified business groups in emerging markets: The lessons from chaebols in Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 21(1/2), 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Kim, H., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2010). Does market-oriented institutional change in an emerging economy make business-group-affiliated multinationals perform better? An institution-based view. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(7), 1141–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. (2008). A forensic study of Daewoo’s corporate governance: Does responsibility for the meltdown solely lie with the chaebol and Korea? Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business, 28(2), 273–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. (2017). Corporate financial structure of South Korea after Asian financial crisis: The chaebol experience. Journal of Economic Structures, 6(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. (2020). Determinants of corporate bankruptcy: Evidence from chaebol and non-chaebol firms in Korea. Asian Economic Journal, 34(3), 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-B., & Yi, C. H. (2006). Ownership structure, business group affiliation, listing status, and earnings management: Evidence from Korea. Contemporary Accounting Research, 23(2), 427–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J. (2001). A bibliometric analysis of physics publications in Korea, 1994–1998. Scientometrics, 50(3), 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R. (2016). Financial weakness and product market performance: Internal capital market evidence. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 51(1), 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W., Lim, Y., & Sung, T. (2007). Group control motive as a determinant of ownership structure in business conglomerates. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 15(3), 213–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., & Lui, S. S. (2015). The impacts of external network and business group on innovation: Do the types of innovation matter? Journal of Business Research, 68(9), 1964–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. T. (1999). Neoliberalism and the decline of the developmental state. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 29(4), 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. T. (2005). DJnomics and the transformation of the developmental state. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 35(4), 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J., & Maeng, K. (2005). The effect of financial liberalization on firms’ investments in Korea. Journal of Asian Economics, 16(2), 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kōsai, Y. (1989). The postwar Japanese economy, 1945–1973. In P. Duus (Ed.), The Cambridge history of Japan volume 6: The twentieth century (pp. 494–538). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, V. S., & Moyer, R. C. (1997). Performance, capital structure and home country: An analysis of Asian corporations. Global Finance Journal, 8(1), 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, I., & Park, C.-Y. (2021). Corporate governance and the efficiency of government R&D grants. Global Economic Review, 50(4), 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.-S., Park, H. W., So, M., & Leydesdorff, L. (2012). Has globalization strengthened South Korea’s national research system? National and international dynamics of the Triple Helix of scientific co-authorship relationships in South Korea. Scientometrics, 90(1), 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung-Sup, C. (1999). Compressed modernity and its discontents: South Korean society in transtion. Economy and Society, 28(1), 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, L. (2002). Financial constraints on investments and credit policy in Korea. Journal of Asian Economics, 13(2), 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambiotte, R., Delvenne, J.-C., & Barahona, M. (2014). Random walks, Markov processes and the multiscale modular organization of complex networks. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering, 1(2), 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B., Gamble, G., Noland, T., & Zhao, Y. (2024). The effects of regulated auditor tenure on opinion shopping: Evidence from the Korean market. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(11), 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-Y., Lee, J.-H., & Gaur, A. S. (2017). Are large business groups conducive to industry innovation? The moderating role of technological appropriability. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 34(2), 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-W., Lee, Y. S., & Lee, B.-S. (2000). The determination of corporate debt in Korea. Asian Economic Journal, 14(4), 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., Ryu, S., & Kang, J. (2014). Transnational HR network learning in Korean business groups and the performance of their subsidiaries. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(4), 588–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Y., Chung, C. Y., & Morscheck, J. (2020). Does geographic proximity matter in active monitoring? Evidence from institutional blockholder monitoring of corporate governance in the Korean market. Global Economic Review, 49(2), 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-C., & Su, H.-N. (2010). Investigating the structure of regional innovation system research through keyword co-occurrence and social network analysis. Innovation, 12(1), 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., Park, K., & Shin, H.-H. (2009). Disappearing internal capital markets: Evidence from diversified business groups in Korea. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(2), 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. J. (2008). The politics of chaebol reform in Korea: Social cleavage and new financial rules. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 38(3), 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J., & Han, T. (2006). The demise of “Korea, Inc.”: Paradigm shift in Korea’s developmental state. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 36(3), 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Rong, Y., Ahmad, U. M., Wang, X., Zuo, J., & Mao, G. (2021). A comprehensive review on green buildings research: Bibliometric analysis during 1998–2018. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(34), 46196–46214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D. H., & Morris, M. L. (2006). Influence of trainee characteristics, instructional satisfaction, and organizational climate on perceived learning and training transfer. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 17(1), 85–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H. (2009). Democratization and the transformation process in East Asian developmental states: Financial reform in Korea and Taiwan. Asian Perspective, 33(1), 75–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.-C., & Jang, J.-H. (2006). Neo-liberalism in post-crisis South Korea: Social conditions and outcomes. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 36(4), 442–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, U., & Kim, C.-S. (2005). Determinants of ownership structure: An empirical study of the Korean conglomerates. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 13(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, I. P., & Mitchell, W. (2004). Two faces: Effects of business groups on innovation in emerging economies. Management Science, 50(10), 1309–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maman, D. (2002). The emergence of business groups: Israel and South Korea compared. Organization Studies, 23(5), 737–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.-S. (2013). Evaluation of board reforms: An examination of the appointment of outside directors. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 29, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.-S., & Verhoeven, P. (2013). Outsider board activity, ownership structure and firm value: Evidence from Korea: Outsider board activity and firm value. International Review of Finance, 13(2), 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.-J., & An, Y. (2023). Interlocking network, banker interlocking director and cost of debt. Global Economic Review, 52(1), 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M. E. J. (2001). The structure of scientific collaboration networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(2), 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, I., & Park, H.-J. (2001). Shooting at a moving target: Four theoretical problems in explaining the dynamics of the chaebol. Asia Pacific Business Review, 7(4), 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, I., Yoon, S. S., & Kim, H. J. (2022). The end of rent sharing: Corporate governance reforms in South Korea. Asia Pacific Business Review, 28(1), 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A., Carvalho, F., & Reis, N. R. (2022). Institutions and firms’ performance: A bibliometric analysis and future research avenues. Publications, 10(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-K., Lee, C., & Jeon, J. Q. (2020). Centrality and corporate governance decisions of Korean chaebols: A social network approach. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 62, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. W., Yoon, J., & Leydesdorff, L. (2016). The normalization of co-authorship networks in the bibliometric evaluation: The government stimulation programs of China and Korea. Scientometrics, 109(2), 1017–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-H., & Lee, K. (2006). Linking the technological regime to the technological catch-up: Analyzing Korea and Taiwan using the US patent data. Industrial and Corporate Change, 15(4), 715–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S., & Yuhn, K. (2012). Has the Korean chaebol model succeeded? Journal of Economic Studies, 39(2), 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. H. (2022). The tax models in Japan and Korea: Concepts and evidence from a comparative perspective. Journal of East Asian Studies, 22(3), 359–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y., Yul Lee, J., & Hong, S. (2011). Effects of international entry-order strategies on foreign subsidiary exit: The case of Korean chaebols. Management Decision, 49(9), 1471–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. S. (2011). Revisiting the South Korean developmental state after the 1997 financial crisis. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 65(5), 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D. J. d. S. (1965). Networks of scientific papers: The pattern of bibliographic references indicates the nature of the scientific research front. Science, 149(3683), 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, C., & Bae, J. (2004). Big business in South Korea: The reconfiguration process. Asia Pacific Business Review, 10(3–4), 302–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugman, A. M., & Oh, C. H. (2008). Korea’s multinationals in a regional world. Journal of World Business, 43(1), 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwak, J. (2019). Dangerous liaisons? State-chaebol co-operation and the global privatisation of development. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 49(1), 104–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheard, P. (1994). Main banks and the governance of financial distress. In M. Aoki, & H. Patrick (Eds.), The Japanese main bank system: Its relevance for developing and transforming economies (pp. 188–230). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, D. (2002). South Korean media industry in the 1990s and the economic crisis. Prometheus, 20(4), 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.-H., & Park, Y. S. (1999). Financing constraints and internal capital markets: Evidence from Korean ‘chaebols’. Journal of Corporate Finance, 5(2), 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J. Y., Hyun, J.-H., Oh, S., & Yang, H. (2018). The effects of politically connected outside directors on firm performance: Evidence from Korean chaebol firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 26(1), 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K., & Wang, Y. (2004). Trade integration and business cycle co-movements: The case of Korea with other Asian countries. Japan and the World Economy, 16(2), 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S. I., & Kim, L. (2020). Chaebol and the turn to services: The rise of a Korean service economy and the dynamics of self-employment and wage work. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 50(3), 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiu, J.-W., Wong, C.-Y., & Hu, M.-C. (2014). The dynamic effect of knowledge capitals in the public research institute: Insights from patenting analysis of ITRI (Taiwan) and ETRI (Korea). Scientometrics, 98(3), 2051–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H. (1973). Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 24(4), 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H., Chung, Y., & Yoon, S. (2022). How can university technology holding companies bridge the Valley of Death? Evidence from Korea. Technovation, 109, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H. K. (2003). The birth of a welfare state in Korea: The unfinished symphony of democratization and globalization. Journal of East Asian Studies, 3(3), 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. H., Joo, B.-K. (Brian), & Chermack, T. J. (2009a). The dimensions of learning organization questionnaire (DLOQ): A validation study in a Korean context. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 20(1), 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. H., Kim, H. M., & Kolb, J. A. (2009b). The effect of learning organization culture on the relationship between interpersonal trust and organizational commitment. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 20(2), 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.-N., & Lee, P.-C. (2010). Mapping knowledge structure by keyword co-occurrence: A first look at journal papers in Technology Foresight. Scientometrics, 85(1), 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczech-Pietkiewicz, E., Radło, M.-J., & Tomeczek, A. F. (2023). Smart and sustainable city management in Asia and Europe: A bibliometric analysis. In R. Dygas, & P. K. Biswas (Eds.), Smart cities in Europe and Asia (1st ed., pp. 1–15). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomeczek, A. F. (2022). The evolution of Japanese keiretsu networks: A review and text network analysis of their perceptions in economics. Japan and the World Economy, 62, 101132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomeczek, A. F. (2023). The rise of the chaebol: A bibliometric analysis of business groups in South Korea (data and graphs) [Dataset]. Mendeley Data. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S., Hossain, L., Abbasi, A., & Rasmussen, K. (2012). Trend and efficiency analysis of co-authorship network. Scientometrics, 90(2), 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2022). VOSviewer manual. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/documentation/Manual_VOSviewer_1.6.18.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Velez-Estevez, A., García-Sánchez, P., Moral-Munoz, J. A., & Cobo, M. J. (2022). Why do papers from international collaborations get more citations? A bibliometric analysis of library and information science papers. Scientometrics, 127(12), 7517–7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Huangfu, Y., Dong, Z., & Dong, Y. (2022). Research hotspots and evolution trends of carbon neutrality—Visual analysis of bibliometrics based on citespace. Sustainability, 14(3), 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. E. (1979). Transaction-cost economics: The governance of contractual relations. The Journal of Law and Economics, 22(2), 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Hou, G., & Wang, J. (2022). Research on digital transformation based on complex systems: Visualization of knowledge maps and construction of a theoretical framework. Sustainability, 14(5), 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N., Kumar, R., & Malik, A. (2022). Global developments in coopetition research: A bibliometric analysis of research articles published between 2010 and 2020. Journal of Business Research, 145, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, E., & Ding, Y. (2012). Scholarly network similarities: How bibliographic coupling networks, citation networks, cocitation networks, topical networks, coauthorship networks, and coword networks relate to each other. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(7), 1313–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, E., Ding, Y., & Zhu, Q. (2010). Mapping library and information science in China: A coauthorship network analysis. Scientometrics, 83(1), 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.-H., & Moon, C. W. (1999). Korean financial crisis during 1997–1998. Causes and challenges. Journal of Asian Economics, 10(2), 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S., & Lee, S. M. (1987). Management style and practice of Korean chaebols. California Management Review, 29(4), 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, T., & Koh, Y. (2022). Remains on the board: Outside directors’ behaviour and their survival chance in Korean firms. Asia Pacific Business Review, 28(1), 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, T., & Rhee, M. (2013). Agency theory and the context for R&D investment: Evidence from Korea. Asian Business & Management, 12(2), 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B., Lee, J., & Byun, R. (2018). Does ESG performance enhance firm value? Evidence from Korea. Sustainability, 10(10), 3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J. (2015). The evolution of South Korea’s innovation system: Moving towards the triple helix model? Scientometrics, 104(1), 265–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J. (2020). The changing dynamics of state–business relations and the politics of reform and capture in South Korea. Review of International Political Economy, 28(1), 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J., & Park, Y. M. (2017). The legacies of state corporatism in Korea: Regulatory capture in the Sewol ferry tragedy. Journal of East Asian Studies, 17(1), 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., & Yuan, J. (2022). Enhanced author bibliographic coupling analysis using semantic and syntactic citation information. Scientometrics, 127(12), 7681–7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Xie, Q., Song, C., & Song, M. (2022). Mining the evolutionary process of knowledge through multiple relationships between keywords. Scientometrics, 127(4), 2023–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Query String (Database: Scopus, Date: 2 February 2023) | Results |

|---|---|

| TITLE-ABS-KEY (“chaebol*” OR “jaebeol*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“business group” OR “business network” OR “corporate group” OR “corporate network” OR “conglomerate” OR “holding company” AND “korea*”) AND PUBYEAR < 2023 AND DOCTYPE (ar OR re) AND LANGUAGE (english) AND SUBJAREA (busi OR deci OR econ OR soci) | 749 |

| Articles with references data (for bibliographic coupling) | 719 |

| Articles with affiliations data (for co-authorship) | 705 |

| Articles with author keywords data (for keyword co-occurrence) | 583 |

| Number of Articles | Community (Color) | Notable Themes | Highly Cited Articles | Citations | Normalized Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 102 | Economic system (violet) | economic systems, developmental state, technological catch-up, crisis, capitalism, neoliberalism, free market, industrialization, military | (Amsden & Hikino, 1994) | 251 | 2.81 |

| (S. J. Chang et al., 2006) | 238 | 2.88 | |||

| (Hobday et al., 2004) | 187 | 3.00 | |||

| (Kyung-Sup, 1999) | 156 | 3.34 | |||

| (K.-H. Park & Lee, 2006) | 127 | 1.54 | |||

| 83 | Corporate governance (green) | corporate governance, ownership structure, internal capital markets, tunneling, propping, family ownership, agency theory, outside directors, executive compensation, corporate social responsibility | (K.-H. Bae et al., 2002) | 628 | 10.00 |

| (Joh, 2003) | 475 | 6.71 | |||

| (Baek et al., 2004) | 436 | 6.99 | |||

| (S. J. Chang, 2003) | 342 | 4.83 | |||

| (Baek et al., 2006) | 292 | 3.54 | |||

| 56 | Business groups in emerging markets (orange) | emerging markets, multinational enterprises, business networks, internal transactions, international expansion, technological innovation | (Khanna & Rivkin, 2001) | 930 | 10.10 |

| (S. J. Chang & Hong, 2000) | 586 | 9.70 | |||

| (Guillen, 2002) | 289 | 4.60 | |||

| (H. Kim et al., 2010) | 176 | 9.44 | |||

| (Mahmood & Mitchell, 2004) | 170 | 2.73 | |||

| 13 | Learning and human capital (gray) | learning organizations, human capital, leadership, work engagement, career satisfaction | (D. H. Lim & Morris, 2006) | 199 | 2.41 |

| (J. H. Song et al., 2009a) | 123 | 5.08 | |||

| (Joo & Lee, 2017) | 83 | 7.98 | |||

| (Joo et al., 2016) | 67 | 8.89 | |||

| (J. H. Song et al., 2009b) | 62 | 2.56 | |||

| 7 | Financial liberalization (gray) | financial liberalization, investment, capital structure, financial constraints, corporate debt | (Krishnan & Moyer, 1997) | 47 | 1.55 |

| (H. Kim et al., 2006) | 33 | 0.40 | |||

| (Koo & Maeng, 2005) | 28 | 1.31 | |||

| (J.-W. Lee et al., 2000) | 27 | 0.45 | |||

| (Laeven, 2002) | 25 | 0.40 |

| Number of Keywords | Community (Color) | Top Keywords | Occurrence Count | Degree Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 59 | Corporate governance and internal markets of chaebol groups (red) | chaebol | 352 | 228 |

| corporate governance | 90 | 101 | ||

| ownership structure | 32 | 43 | ||

| family firms | 30 | 52 | ||

| r&d | 22 | 40 | ||

| related-party transactions | 22 | 32 | ||

| agency problem | 21 | 40 | ||

| control-ownership disparity | 20 | 36 | ||

| emerging market | 19 | 39 | ||

| firm value | 19 | 33 | ||

| controlling shareholder | 17 | 31 | ||

| internal capital market | 15 | 20 | ||

| institutional blockholding | 12 | 21 | ||

| tunneling | 12 | 23 | ||

| diversification | 11 | 17 | ||

| 52 | Developmental state and liberalization of Korea (blue) | south korea | 150 | 171 |

| developmental state | 30 | 51 | ||

| neoliberalism | 25 | 42 | ||

| institutional change | 20 | 41 | ||

| china | 13 | 34 | ||

| japan | 13 | 31 | ||

| technological capabilities | 13 | 21 | ||

| globalization | 12 | 24 | ||

| taiwan | 11 | 21 | ||

| economic development | 10 | 19 | ||

| 26 | Corporate social responsibility and ESG (yellow) | corporate social responsibility | 44 | 65 |

| management | 17 | 35 | ||

| competition | 9 | 23 | ||

| environmentally sensitive industries | 8 | 17 | ||

| esg | 8 | 20 | ||

| accounting | 7 | 21 | ||

| ceo | 7 | 14 | ||

| discretionary accruals | 7 | 19 | ||

| 24 | Innovation and knowledge (dark gray) | innovation | 32 | 54 |

| human resource management | 17 | 24 | ||

| knowledge | 13 | 20 | ||

| learning | 12 | 32 | ||

| patent | 10 | 21 | ||

| subsidiary performance | 9 | 15 | ||

| 19 | Financial crisis in East Asia (dark blue) | financial crisis | 44 | 71 |

| investment | 22 | 35 | ||

| government regulation | 16 | 35 | ||

| credit ratings | 14 | 26 | ||

| korean stock market | 8 | 18 | ||

| performance | 8 | 21 | ||

| 18 | Characteristics of Korean firms (orange) | korean firms | 13 | 29 |

| cash holdings | 10 | 19 | ||

| culture | 9 | 17 | ||

| capital structure | 8 | 18 | ||

| risk | 7 | 18 | ||

| 17 | Information asymmetries and forecasts (pink) | information asymmetry | 14 | 30 |

| group affiliation | 13 | 24 | ||

| analyst following | 10 | 18 | ||

| banking sector | 9 | 26 | ||

| forecast accuracy | 9 | 13 | ||

| 15 | SMEs and business networks (dark green) | smes | 19 | 49 |

| business network | 8 | 20 | ||

| strategy | 8 | 21 | ||

| networks | 7 | 24 | ||

| resource-based view | 7 | 21 | ||

| social network analysis | 7 | 16 | ||

| 8 | Earnings quality and sustainability (green) | earnings quality | 9 | 21 |

| korean market | 7 | 19 | ||

| sustainable corporate governance | 7 | 16 | ||

| 6 | Multinational firms and FDI (light gray) | foreign direct investment | 18 | 41 |

| mnc | 12 | 27 | ||

| asia | 8 | 29 | ||

| 4 | Labor unions (gray) | labor union | 8 | 16 |

| 2 | Electronics suppliers (gray) | electronics industry | 2 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tomeczek, A.F. The Rise of the Chaebol: A Bibliometric Analysis of Business Groups in South Korea. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110658

Tomeczek AF. The Rise of the Chaebol: A Bibliometric Analysis of Business Groups in South Korea. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(11):658. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110658

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomeczek, Artur F. 2025. "The Rise of the Chaebol: A Bibliometric Analysis of Business Groups in South Korea" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 11: 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110658

APA StyleTomeczek, A. F. (2025). The Rise of the Chaebol: A Bibliometric Analysis of Business Groups in South Korea. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(11), 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110658