1. Introduction

Household debt is increasingly recognized not only as a macroeconomic indicator but also as a critical source of financial risk. Credit access plays a crucial role in shaping household financial behavior and debt levels, acknowledging that it can facilitate consumption smoothing, investment, and economic participation, yet excessive indebtedness often heightens household vulnerability, constrains future income, and generates financial fragility. Prior research highlights this dual role of debt: while it can stimulate short-term growth (

Mian et al., 2015;

Juselius & Drehmann, 2020), sustained repayment burdens undermine long-term financial stability (

Lombardi et al., 2017;

Tunc & Kilinc, 2023).

From a risk management perspective, household debt represents both opportunity and exposure to significant vulnerabilities that depend upon behavioral and structural factors.

Abdelzaher (

2019),

Wabwire (

2019), and

Mansour et al. (

2024) find that both formal and informal credit play complementary roles in enhancing household liquidity, allowing families to cope with emergencies, smooth consumption, and finance productive activities. However, excessive or poorly managed borrowing can eventually lead to over-indebtedness and strategic insolvency, transforming a liquidity-enhancing tool into a source of long-term financial vulnerability (

Vandone, 2009;

Sullivan et al., 2020;

Teulings et al., 2023).

Thailand’s macroeconomic and social context further underscores the relevance of this study. The country is classified as an upper-middle-income economy, with a nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of approximately USD 515 billion in 2023 and GDP per capita around USD 7182 (

The World Bank, 2024). Real GDP growth averaged 1.9 percent in 2023, reflecting sluggish post-pandemic recovery and export stagnation. Headline inflation remained subdued, averaging 0.4 percent in 2024, while the policy interest rate of the Bank of Thailand stood at 2.25 percent at year-end (

Bank of Thailand, 2024). Despite macroeconomic stability and moderate inflation, income growth has been limited and household debt levels remain among the highest in Asia, exceeding 80 percent of GDP. In social terms, Thailand achieved a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.803 in 2022, ranking 66th globally and classified as “very high human development” (

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2023). This combination of moderate growth, high debt, and relatively advanced human development highlights a paradox of financial vulnerability amid structural progress, providing the backdrop for understanding credit segmentation and debt risk in the Thai context.

Household debt remains a persistent puzzle in Thailand and has increasingly attracted scholarly and policy attention. The risks associated with household debt have become especially pressing. Thailand’s household debt has exceeded the safe threshold (80 percent of GDP) since 2015. Private consumption constitutes 50–60 percent of GDP, and rising debt has supported economic activity in recent years. However, the household debt-to-GDP ratio has exceeded 80 percent since 2020, peaking at 90.8 percent—well above levels typically linked to financial instability. During the two years of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021), the ratio spiked further to around 90 percent, driven by income shocks, job losses, and deferred debt payments. The pandemic caused a sharp increase in debt levels as households borrowed more to compensate for income loss, thereby limiting future consumption and weakening economic resilience.

The watchful tendency is likely to continue at least until 2027, according to the

Bank of Thailand (

2024). This reflects the insufficiency of debt-reduction processes and credit-relief mechanisms such as six-month payment holidays, restructuring schemes, and the “You Fight, We Help” program. Furthermore, approximately three-quarters of formal borrowing is directed toward consumption rather than investment, signaling structural income insufficiency and a fragile debt profile. Sustained debt-to-GDP ratios above 80 percent can adversely affect long-term growth, undermine financial stability, and deepen household vulnerability—an urgent issue that warrants policy attention.

Informal debt remains a persistent and consequential component of household finance, particularly in settings where formal credit markets are thin, costly, or difficult to access. Despite efforts to expand financial inclusion, many Thai households continue to rely on unregulated lenders who typically charge 10–20 percent monthly interest (

Pinitjitsamut & Suwanprasert, 2022). Such conditions not only increase repayment risk and over-indebtedness but also expose borrowers to coercive collection practices and social harm. Unlike formal credit, informal debt is rarely recorded in systematic databases, limiting policymakers’ ability to assess aggregate risks or design effective interventions. Nevertheless, informal debt is not merely a symptom of exclusion but also an adaptive mechanism—a form of financial resilience bridging the gap between individual vulnerability, social solidarity, and systemic inequality (

Xu et al., 2025;

Chanda et al., 2025). Hence, both formal and informal credit play essential and interrelated roles in modern financial systems.

These dynamics raise important questions about financial behavior, institutional constraints, and structural imbalances that influence borrowing and repayment patterns across Thai households. This study contributes to the household finance and risk management literature by examining both formal and informal borrowing channels and their implications for financial vulnerability. Using cross-sectional data from 6949 individuals across 77 provinces collected by the Thailand Trade Policy and Strategy Office in 2021, this study employs multinomial regression models to analyze how demographic, occupational, and income characteristics influence borrowing choices. The dataset is the most recent nationally representative household debt survey available and uniquely includes detailed information on informal credit and credit sources. Although the data may be somewhat dated, they provide valuable insights into borrowing behavior during a period of heightened financial stress following the COVID-19 pandemic.

By linking household characteristics to borrowing outcomes, this study identifies the risk factors driving reliance on informal lending and the conditions under which households face heightened exposure to debt traps. The findings reveal how vulnerabilities are structured by region, occupation, and income, underscoring the systemic risks posed by unequal access to regulated financial institutions. This study advances the literature by integrating demographic, occupational, and loan-purpose factors within a single empirical framework, offering a comprehensive view of debt segmentation between formal and informal markets in Thailand. It further contributes novel evidence on “dual borrowing” behavior—simultaneous reliance on both formal and informal credit—using recent post-pandemic data from an emerging economy context. Beyond contributing to empirical work on household debt in emerging economies, the results carry clear policy implications: expanding access to formal credit, promoting microfinance, and strengthening financial protection frameworks are essential to reducing household financial risk and enhancing resilience.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related literature on household debt and financial risk;

Section 3 describes the data and methodology;

Section 4 presents the empirical results;

Section 5 discusses risk management and policy implications; and

Section 6 concludes.

2. Literature Review

Household borrowing is consistently shown to be influenced by behavioral biases, financial literacy, and structural constraints, yet the mechanisms differ across socio-economic contexts.

Campbell (

2006) defines household finance as a field in which families face complex lifetime decisions under borrowing constraints and imperfect information, emphasizing that financial mistakes are more common among poorer and less-educated households. This view is affirmed by

Soll et al. (

2013) and

Telyukova (

2013), who, respectively, provide evidence of cognitive biases and limited financial literacy, and of liquidity-management strategies through the joint holding of debt and liquid assets. Extending this behavioral foundation,

Ilan and Mugerman (

2025) demonstrate that low-income borrowers often make misguided mortgage choices by anchoring to current rather than expected inflation, highlighting how financial literacy moderates susceptibility to cognitive bias—similar to the findings of

Teulings et al. (

2023),

Barberis et al. (

2015) and

Lusardi and Mitchell (

2014). Their results also extend behavioral finance theory into the mortgage domain.

From a macro-economic perspective, research consistently shows that household indebtedness creates risks extending beyond balance sheets, shaping both financial stability and household vulnerability.

Denkyirah et al. (

2016) and

Baiyegunhi et al. (

2010) demonstrate that socioeconomic characteristics strongly influence loan access in developing economies, while

Dunn and Mirzaie (

2023) highlight how personal attributes drive variation in debt-related stress, with implications for work performance, family stability, and overall financial resilience. These findings confirm that debt is not merely an economic outcome but also a source of financial fragility that exposes households to repayment difficulties and long-term vulnerability.

The influence of family structure on debt-related stress remains contested.

Van Winkle and Monden (

2022) report that the presence of children does not necessarily increase financial pressure, echoing

Albertini (

2016), who attributes this to the mitigating effects of intergenerational transfers and social safety nets.

Kowalski et al. (

2023) nuance this perspective by showing that younger parents are more likely to experience debt-related stress than older ones. These findings suggest that, while family and policy support can buffer against financial fragility, specific household types remain exposed to elevated risk.

Gender disparities represent another dimension of financial vulnerability.

Dunn and Mirzaie (

2023) find that women experience greater stress associated with borrowing and repayment, while

Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (

2013) argue that cultural and legal barriers constrain women’s access to formal banking channels. These constraints often force women to rely on informal credit, thereby increasing their exposure to predatory practices and high repayment risks. This underscores how gender inequality translates directly into differentiated credit-risk profiles.

Education, income, and age also shape household exposure to financial risk.

Govindapuram et al. (

2023) find that higher education, stable income, and middle age (40–60 years) are associated with improved access to formal finance, which reduces reliance on informal credit and strengthens household financial resilience. Conversely, lower education levels and unstable employment heighten the probability of financial exclusion, increasing dependence on informal borrowing and thereby amplifying household risk exposure. Similarly,

Dwyer (

2018);

Li (

2023);

Chanda et al. (

2025);

Xu et al. (

2025) show that financial inequality and institutional access shape household indebtedness across different income and education groups. Lower-income and less-educated households generally rely on informal sources of borrowing, whereas higher-educated groups gain better access to formal credit and use debt for investment rather than consumption purposes.

Further,

Green (

2025) concurs with these findings, emphasizing that education increases financial access but that gender and age intersect to produce unequal debt risks within rural households. He also highlights that agricultural credit and microfinance have become central to rural household finance in Cambodia. Poorer and less-educated families rely on both formal and informal loans to sustain their livelihoods and repay existing debts, consistent with

Bylander (

2015) and

Guérin (

2014). However, policies that restrict access to formal credit must be implemented carefully, as excessive regulation can drive households to rely more heavily on informal borrowing channels, as noted by

Xu et al. (

2025).

In this context, the network perspective of financial interdependencies offers additional insights.

Bahari et al. (

2024) use correlation and network analysis to show that during the COVID-19 pandemic the interdependence among financial-sector stocks in Malaysia rose significantly: networks became more connected and only contained positive correlations, while modularity peaked, indicating tighter but more risk-prone communities. This suggests that structural financial conditions and systemic interconnectedness play a critical role during crises—a result that resonates with our interest in how formal vs. informal debt channels may amplify household vulnerability in emerging markets.

Overall, the literature suggests that household indebtedness is shaped by multiple factors—personal characteristics, family support, gender norms, and financial inclusion—that collectively determine household financial risk. Yet much of this evidence is drawn from developed or comparative contexts, leaving gaps in understanding the debt experience in emerging economies where informal lending remains widespread. Thailand presents a critical case: household debt levels exceed internationally recognized thresholds for financial stability, while informal lending practices persist without adequate regulation or data oversight. By analyzing both formal and informal borrowing, this study contributes to the financial-risk-management literature by identifying the socioeconomic determinants of credit exposure and highlighting policy measures needed to mitigate household vulnerability in emerging markets.

3. Data and Methodology

This study draws on individual-level cross-sectional data collected by the Thailand Trade Policy and Strategy Office in September 2021. The survey covers Bangkok and 77 provinces nationwide, resulting in a total of 6949 respondents.

1 Because the survey was conducted in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, borrowing behaviors should be interpreted with caution, as household debt levels may reflect temporary financial stress in addition to longer-term patterns. Nevertheless, the dataset provides a rare opportunity to analyze both formal and informal borrowing decisions within a nationally representative sample.

3.1. Data Descriptives

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents. Nearly 60 percent are female, and the majority fall within the middle-aged range of 30–49 years. Educational attainment is relatively high, with most respondents holding at least a bachelor’s degree, while approximately 40 percent report vocational qualifications or lower. Consistent with these educational profiles, around 37 percent report a primary monthly income between more than 10,000 and 20,000 THB (≈304.90–609.80 USD)—a level typical for lower- to middle-skilled occupations.

Reliance on primary income streams is notable. More than half of respondents report no additional earnings, and nearly one-third earn less than 5000 THB per month (≈152.45 USD) from supplementary activities. Such limited income diversification underscores the vulnerability of households to financial shocks and increases their exposure to debt-related risks.

Occupational structure further illustrates potential credit dependencies. Farmers account for 27 percent of the sample, many of whom are eligible for loans from the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives, a specialized public institution providing formal credit to agricultural households. By contrast, other occupational groups—including freelancers and service workers—often lack such institutional access, making them more reliant on informal lenders.

Regional distribution also reflects structural disparities in financial access. Almost 30 percent of respondents reside in the northeastern region, while 28 percent live in the central region, including Bangkok. This diversity in geography and occupation strengthens the analysis by capturing heterogeneity in exposure to formal financial institutions and the persistence of informal lending channels. Importantly, such variation allows for the identification of population groups most at risk of financial fragility and indebtedness traps.

Table 2 shows that approximately half of respondents hold debt exclusively with formal financial institutions, while only a small share rely solely on informal lenders. Nevertheless, the presence of informal borrowing—despite its limited proportion—remains a critical concern given the high repayment risks and lack of regulatory oversight. Interestingly, the aggregate value of formal and informal debts is comparable, suggesting that even relatively few informal borrowers carry substantial financial exposure.

Repayment burdens further underscore household vulnerability. Most indebted respondents reported monthly repayments between 1000 and 5000 THB (≈30.49–152.45 USD), equivalent to roughly one-quarter to one-half of their total monthly income. Such ratios indicate elevated debt-service risk and limited financial resilience, especially in the event of income shocks.

Loan purposes reveal additional risk patterns. Consumption and employment-related expenses are the dominant motivations for borrowing. Given the post-COVID-19 context of the survey, a high share of households may have relied on credit to smooth consumption during economic disruption. In parallel, government-sponsored low-interest business loans introduced as part of economic stimulus programs appear to have driven borrowing for job-related purposes. While these measures provided short-term relief, they may also have encouraged greater household leverage, potentially amplifying financial fragility if repayment difficulties emerge in subsequent years.

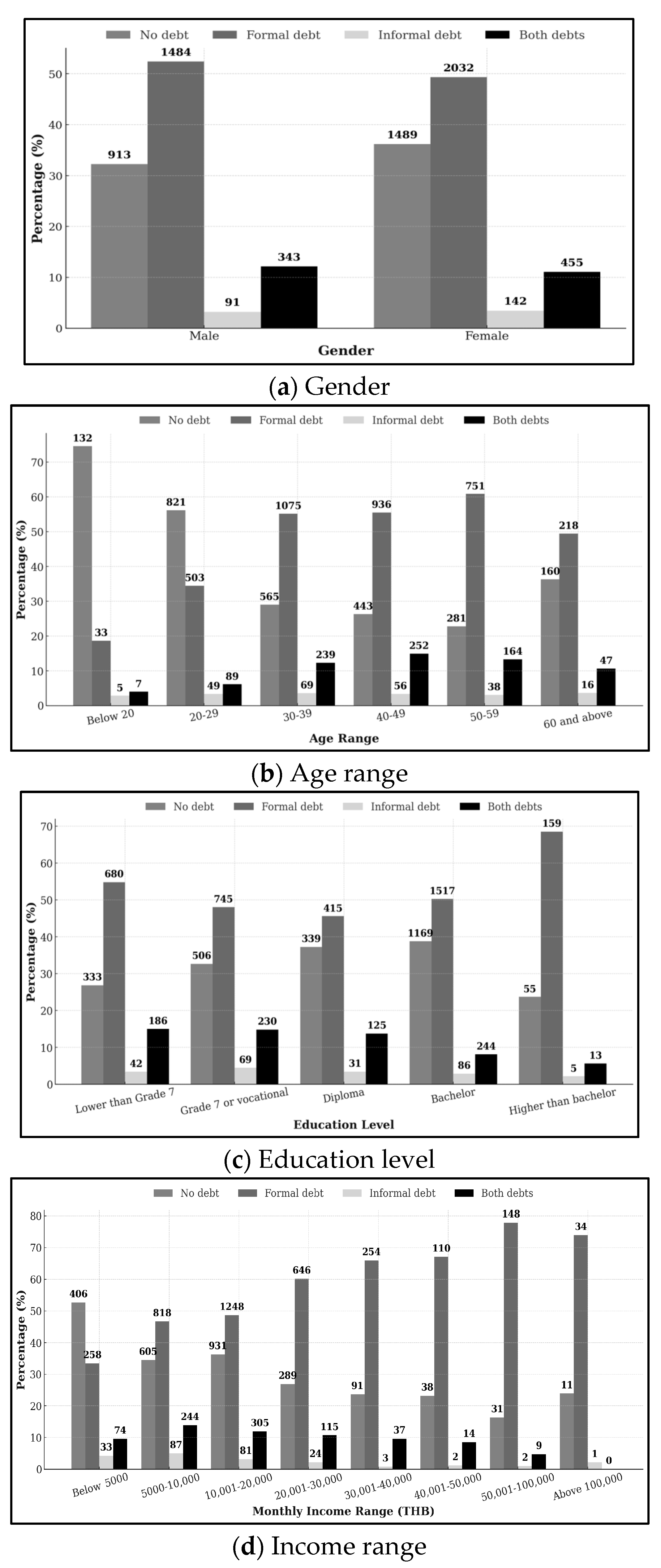

Cross-tabulations between household debt status and personal characteristics reveal distinct behavioral patterns in credit accessibility and debt composition. When comparing debt patterns by gender, in

Figure 1a, the differences are relatively minor (

= 12.4855,

p-value = 0.006). Male borrowers are slightly more represented in formal lending (52.4 percent) than female borrowers (49.3 percent), whereas women are more likely to report being debt-free (36.2 percent compared with 32.3 percent for men). The proportion of individuals holding both formal and informal debts is nearly identical between the two groups—around 11–12 percent—indicating broadly similar financial behaviors among men and women.

Across age groups shown in

Figure 1b, individuals aged 30 to 59 years exhibit the highest tendency toward formal borrowing, with more than half reporting debt obligations within the formal financial system (

= 602.4913,

p-value = 0.000). This pattern reflects the life-cycle stage of financial maturity, when individuals are typically in their prime earning years—supporting families, investing in housing, and managing long-term consumption plans. In contrast, those under 20 years old largely remain debt-free (74.6 percent), as their consumption is still supported by parents and their access to credit remains limited. Meanwhile, individuals aged 40–49 begin to show a rising share of multiple debt holdings, consistent with the life-cycle theory of consumption and saving. This suggests that as households progress through mid-life, borrowing often increases to smooth consumption and maintain living standards during high-expense phases such as child-rearing and mortgage repayment.

In terms of education level shown in

Figure 1c, indebtedness tends to rise with higher educational attainment (

= 152.4203,

p-value = 0.000). Individuals holding bachelor’s degrees or higher report the largest share of formal debt—around 50 to 69 percent—reflecting their greater financial awareness, access to credit information, and stronger links to regulated financial institutions. By contrast, those with less than a Grade 7 education still participate in formal borrowing to a considerable extent (about 54.8 percent), yet a meaningful proportion of them also hold both formal and informal debts (roughly 15 percent). This mixed borrowing behavior suggests that while education facilitates entry into formal credit markets, limited financial stability among lower-educated groups may still compel them to rely on informal lending networks to smooth consumption or cope with income volatility. Such a pattern underscores the persistence of financial inequality in Thailand’s credit environment.

There is a relationship between debt status and income, as shown in

Figure 1d (

= 324.2680,

p-value = 0.000). As earnings increase, the prevalence of formal borrowing grows steadily—from roughly one-third (33 percent) among those earning below 5000 THB per month (≈152.45 USD) to nearly four-fifths (77 percent) among individuals with monthly incomes above 50,000 THB (≈1524.50 USD). This pattern reflects how income capacity enhances creditworthiness, enabling higher earners to access regulated financial markets and structured loan products. In contrast, lower-income households are more often found in the “no debt” category—not necessarily by choice but often due to credit constraints or lack of collateral. This distribution highlights how income not only shapes borrowing behavior but also reflects broader inequalities in financial inclusion and access to institutional credit.

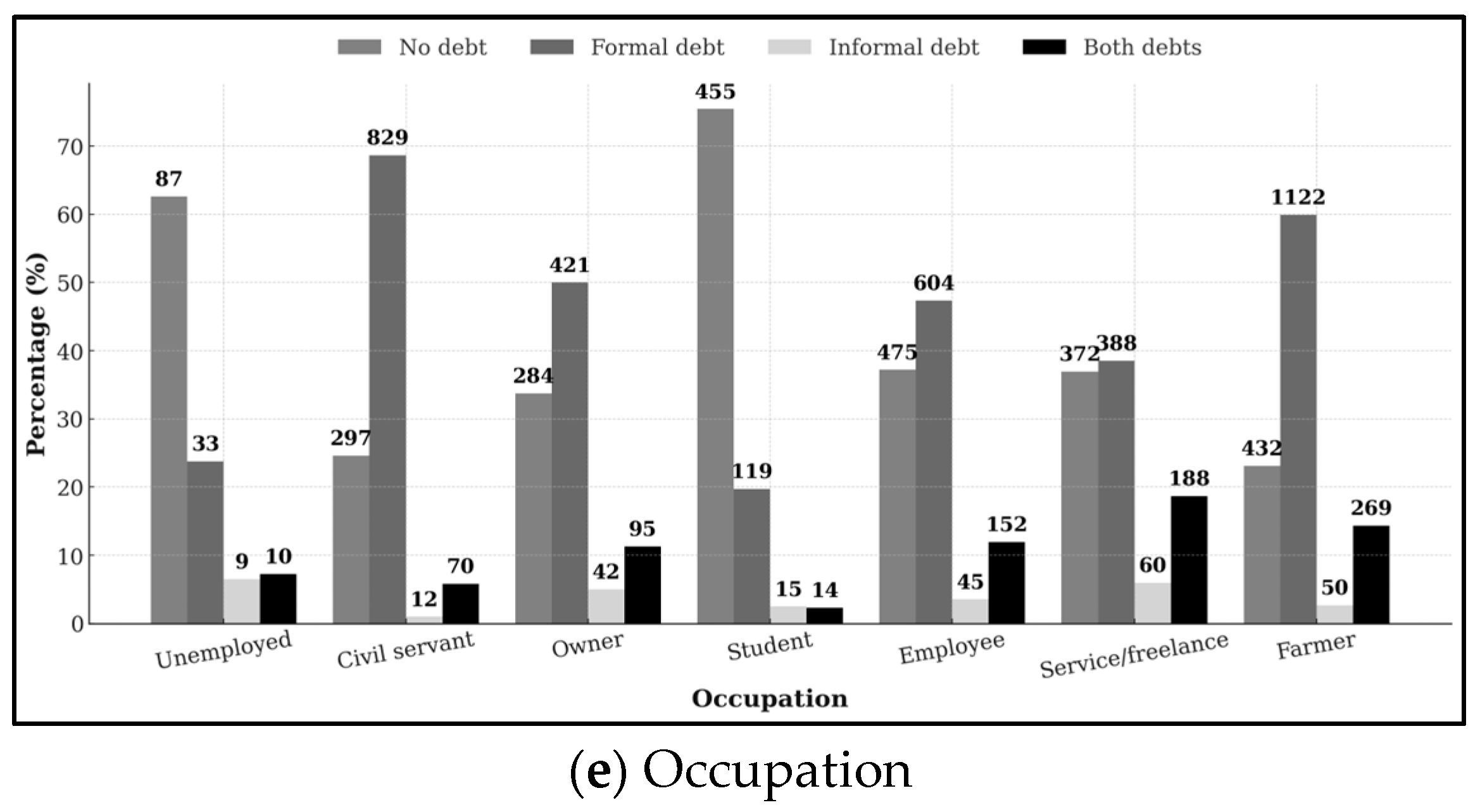

Finally, in

Figure 1e, debt composition differs markedly across occupational groups (

= 903.4299,

p-value = 0.000). Civil servants exhibit the highest share of formal borrowing (68.6 percent), reflecting the advantages of stable employment, predictable income streams, and easier access to institutional credit. In contrast, students show very limited debt participation, with more than three-quarters reporting no debt—consistent with their life-cycle stage, where income is minimal and financial dependence remains high. Meanwhile, farmers and self-employed or freelance workers display the highest exposure to both formal and informal debts, underscoring their economic precarity and limited access to secure financial channels. This dual borrowing pattern highlights how occupational instability often pushes individuals toward informal credit markets to manage liquidity and seasonal income fluctuations.

3.2. Estimation Methodology

Our samples can be divided into four groups based on their debt status: people who have (1) no debt, (2) only formal debt, (3) only informal debt, and (4) both formal and informal debt. Consequently, multinomial logistic regression is applied in this study to investigate factors influencing people to have different debt statuses as follows:

From the above specification,

indicates the probability of being debt-free while

indicates people with only formal, informal, and both formal and informal debt, respectively. The vector of explanatory variables

includes personal characteristics such as gender, age, education, income, occupation, and region.

Table 1 presents the details of these variables. Individuals without debt serve as the base group. In addition, a version of the model excluding the debt-free group is also estimated, as more detailed variables are available for indebted individuals, such as debt impact, repayment length, loan objectives, and loan formats.

According to the multinomial logistic regression, the marginal effects capture the probability of being in debt (or not) across different loan sources. Simply put, the results illustrate the factors influencing Thai people’s borrowing decisions from various sources.

A limitation of the multinomial logit model is the independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA) assumption, which implies that adding a new alternative does not affect the relative odds between existing alternatives. One approach to relax and test this assumption is to use a hierarchical structure such as the nested logit model. We additionally conducted an IIA test using the nested logit model, and all results are reported in the

Appendix A. Generally, our results do not indicate any inconsistency with the IIA assumption. Moreover, the directions and levels of significance of the coefficients from the nested logit model are generally consistent with those from the multinomial logit models.

4. Empirical Results

Table 3 presents the multinomial regression estimates. Column (1) reports the marginal effects for debt-free households, while Columns (2)–(4) show the outcomes for formal debt, informal debt, and combined formal–informal debt, respectively. Our estimations may suffer from omitted variable bias. However, in all specifications, we have already used all available variables from the survey conducted by the Thailand Trade Policy and Strategy Office; therefore, no additional variables are available to serve as instruments. For example, gambling addiction may increase the likelihood of indebtedness, but this information is not included in the survey. Nevertheless, such an omitted variable might not bias our estimates if it is uncorrelated with the explanatory variables. For instance, if individuals across all regions and occupations have an equal probability of gambling addiction, this variable would not bias the coefficients for region or occupation estimated below.

Age and income emerge as central determinants of household debt exposure. Transitioning from the 30–39 age group to the 40–49 group decreases the probability of being debt-free by 3.63 percent (Column 1), while increasing the likelihood of formal borrowing by 2.72 percent (Column 2). However, age has no significant effect on informal debt (Column 3), indicating that life-cycle effects operate primarily within regulated credit markets. Total income shows a similar pattern: higher income reduces the likelihood of being debt-free by 2.25 percent (Column 1) and increases the probability of formal borrowing by 4.54 percent (Column 2), while significantly reducing informal debt reliance by 1.49 percent (Column 3). These findings confirm that higher-income households are integrated into formal markets—where risks center on over-leverage and repayment burdens—while lower-income groups face exclusion and are pushed toward informal lending, where exposure to predatory practices is greatest. Age is positively associated with holding both formal and informal debts (Column 4), while income is negatively related, implying that older but lower-income individuals face the most significant probability of dual borrowing.

2 Occupational differences reveal distinct vulnerabilities. Farmers and civil servants are substantially more likely to rely on formal debt (Column 2), reflecting access to institutional lending such as cooperatives and the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives. By contrast, unemployed and retired individuals, business owners, employees in unstable jobs, and service providers/freelancers face a higher probability of relying on informal lenders (Column 3). These results indicate that while certain occupational groups benefit from structured, regulated lending channels, others remain systematically excluded and exposed to repayment risk. Service providers and freelancers, in particular, display the highest probability of holding both formal and informal debts (Column 4), highlighting the precarious position of non-traditional workers whose lack of collateral or stable income pushes them into dual indebtedness. This dual exposure amplifies household financial fragility by combining leverage risk in formal markets with repayment risk in informal markets. Farmers, business owners, employees, and the unemployed or retired show a higher probability of holding both types of debt compared to civil servants and students (Column 4). Service providers and freelancers stand out as the group with the most consistent and significant dual exposure, underscoring their heightened vulnerability to financial fragility.

Regional disparities further demonstrate segmented credit access. Relative to Bangkok, households in the northeastern and northern regions are 10–12 percent less likely to be debt-free (Column 1), indicating a higher probability of borrowing. At the same time, these regions exhibit significantly greater reliance on formal credit (Column 2), suggesting that cooperative and state-supported institutions have effectively expanded access in rural areas. Conversely, residents of Bangkok and the southern region are more dependent on informal credit (Column 3). This regional divide highlights how informal lending persists not only in remote areas but also in urbanized regions, where rapid consumption needs and gaps in formal financial access sustain demand for unregulated credit.

Taken together, these results reveal a clear segmentation of credit risk in Thailand. Higher-income and institutionally connected groups manage risk through formal borrowing channels, while low-income and non-traditional workers remain disproportionately reliant on informal markets. Regional patterns further suggest that informal lending remains embedded even in economically dynamic regions, sustaining systemic risk at both the household and aggregate levels. Since the present study uses only a one-year dataset collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, the results may therefore reflect financial stress caused by the pandemic.

Table 4 reports the results of the multinomial logit model restricted to indebted individuals, where additional debt-related characteristics are included as explanatory variables. Unlike the broader analysis in

Table 3, this specification allows us to examine how loan objectives, repayment terms, debt impact, and credit formats shape household exposure to different borrowing channels.

Debt impact and repayment length provide key insights into household financial fragility. Respondents reporting greater impacts of debt on expenditure are significantly more likely to hold both formal and informal debts, while the likelihood of holding only one type of debt declines. This suggests that households experiencing acute repayment pressure are forced to diversify across credit channels, thereby compounding their risk exposure. Repayment horizon also matters: longer repayment terms are associated with formal borrowing, reflecting the ability of regulated institutions to extend repayment schedules. In contrast, informal loans, which typically impose short repayment cycles, trap borrowers in high-frequency repayment risks and increase financial stress.

Loan objectives significantly shape debt risk exposure. Borrowing for medical or educational purposes increases reliance on informal or dual borrowing, consistent with the view that essential expenditures often push vulnerable households into high-cost credit. These findings align with

Fan (

2010), who shows that necessary consumption frequently drives borrowing decisions, and with

Lusardi and Tufano (

2015), who emphasize how debt literacy gaps exacerbate reliance on costly financial products. By contrast, objectives such as housing or employment-related investment are more likely to be financed through formal channels, though often accompanied by additional informal loans when formal credit alone is insufficient.

Loan formats further underscore structural inequalities in financial access. Respondents borrowing through credit cards, commercial banks, or cooperatives are significantly less likely to rely on informal credit, indicating the protective effect of access to regulated financial products. In contrast, loans obtained via pawnshops, cash cards, and nano-finance providers increase the likelihood of dual borrowing, exposing households to multiple repayment obligations and a higher risk of debt spirals. These findings reflect persistent inequality in financial access, where households excluded from mainstream financial institutions rely disproportionately on semi-formal and informal providers with higher costs and greater risks.

Overall, the results in

Table 4 reinforce and extend the earlier findings: indebted households face stratified risks depending not only on their socioeconomic characteristics but also on the structure and purpose of their loans. Dual borrowing emerges as a key marker of financial fragility, particularly among low-income, older, and non-traditional workers, as well as those borrowing for essential expenditures through high-cost lending formats. These dynamics highlight the urgent need for policies that expand safe credit options, regulate semi-formal lenders, and provide debt restructuring mechanisms to reduce household vulnerability.

5. Conclusions and Discussions

This study examined the determinants of individual borrowing in Thailand, with particular attention to the risks associated with formal and informal credit markets. The analysis is based on nationally representative survey data from 6949 individuals across 77 provinces, collected in a single year in 2021. A multinomial regression model is employed to analyze how demographic, occupational, and regional factors influence debt choices. Our findings reveal a segmented credit landscape: older and higher-income households integrate more fully into formal markets, while low-income, unemployed, and non-traditional workers remain disproportionately reliant on informal lending. Regional disparities further highlight uneven financial access, with households in Bangkok and the South showing greater exposure to unregulated credit sources. Unlike previous studies, our analysis integrates demographic, occupational, and loan-purpose variables during the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing a more comprehensive understanding of “dual borrowing” behavior across Thailand’s regions.

The findings underscore the heterogeneity of household credit risk in Thailand, while aligning with and extending prior literature on debt, financial fragility, and credit market segmentation. Age and income emerge as central determinants of borrowing outcomes. Older and higher-income households are more likely to hold formal debts, consistent with

Lombardi et al. (

2017), who argue that higher earnings and asset accumulation increase leverage capacity within regulated markets. At the same time, our results confirm that lower-income households are disproportionately reliant on informal loans, echoing

Pinitjitsamut and Suwanprasert (

2022), who highlight the persistent role of high-cost informal lending in Thailand. This divergence in borrowing channels indicates a dual-risk structure: while wealthier households face risks of over-leverage within formal systems, poorer households remain exposed to predatory lending and repayment shocks in unregulated markets (

Chanda et al., 2025). By documenting this dual-risk structure using recent data, our study provides fresh empirical evidence from Thailand that complements global findings by

Karaivanov and Kessler (

2018) on the coexistence of formal and informal credit networks.

Occupational patterns reinforce this segmentation. Farmers and civil servants predominantly access formal credit, supported by institutional mechanisms such as cooperatives and the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives (BAAC). Similar to findings by

Menkhoff and Rungruxsirivorn (

2011),

Green and Bylander (

2021), and

Green (

2025), these results demonstrate how targeted financial programs can reduce reliance on informal credit in specific sectors. Conversely, freelancers, service workers, and small business owners are significantly more likely to rely on informal or mixed borrowing channels. This aligns with

Dunn and Mirzaie (

2023), who emphasize that unstable employment and weak financial security increase vulnerability to debt-related stress, and with

Chichaibelu and Waibel (

2017), who show how multiple borrowing can entrap households in cycles of over-indebtedness. Our framework further advances this discussion by jointly analyzing occupational segmentation and loan purposes—dimensions often treated separately in previous household finance research (e.g.,

Ampudia et al., 2016;

Campbell, 2006).

Regional disparities also reveal systemic risk exposures. Our finding that households in Bangkok and the South are more dependent on informal lenders contrasts with the North and Northeast, where formal financial access is more widespread. This mirrors

Kislat (

2015), who found that regional variation in Thailand continues to shape informal borrowing practices, and extends the evidence by showing how such disparities persist even after extensive financial inclusion initiatives. By embedding regional heterogeneity within a single empirical model, this study offers new insights into the geography of financial vulnerability—a dimension rarely captured in cross-sectional household finance studies. These results suggest that financial exclusion is not confined to rural areas (

Green, 2025) but can also manifest in urban contexts where informal credit markets remain active.

Additional results highlight the role of loan purpose and debt format in amplifying household financial risk. Borrowing for medical or educational purposes increases reliance on informal lenders, consistent with

Fan (

2010) and

Sun and Yannelis (

2016), who emphasize how essential expenditures drive borrowing behavior. Similarly, our findings that pawnshops, nano-finance, and cash cards are strongly linked to dual indebtedness confirm prior concerns by

Lusardi and Tufano (

2015),

Telyukova (

2013),

Li (

2023),

Chanda et al. (

2025), and

Xu et al. (

2025) that limited debt literacy and constrained financial options push vulnerable consumers toward high-cost lending formats. By contrast, access to regulated credit products such as credit cards and cooperative loans appears to shield households from informal debt reliance, suggesting that expanding affordable formal financial products could mitigate risk exposure (

Guérin, 2014;

Bylander, 2015;

Green, 2025). These loan-purpose results uniquely connect micro-level borrowing motives with the structure of formal and informal credit access, offering novel behavioral evidence from Thailand’s financial landscape.

Taken together, these findings position household debt in Thailand within a broader framework of financial fragility. They confirm the global concern, raised by

Mian et al. (

2015) and

Juselius and Drehmann (

2020), that household debt can simultaneously drive short-term consumption growth and long-term vulnerability. At the micro level, however, our evidence highlights the unequal distribution of risks across demographic, occupational, and regional groups. As in the family-stress models tested by

Valerie Heintz-Martin et al. (

2022), debt in Thailand not only reflects macroeconomic conditions but also household-specific vulnerabilities that shape financial resilience. Our contribution, therefore, lies in bridging the gap between macro-level credit segmentation theories and micro-level behavioral evidence, providing a contextualized understanding of household finance in an emerging economy.

From a risk-management perspective, these results underline the need for a two-pronged approach. First, policies must address over-leverage risks among middle- and higher-income households integrated into the formal sector. Second, targeted financial inclusion measures are necessary to reduce dependence on informal lenders among lower-income and non-traditional workers. Expanding microcredit, promoting cooperative-based lending, and regulating semi-formal credit providers could mitigate household-level financial stress while enhancing systemic stability. Furthermore, recognizing “dual borrowers” as a distinct risk category offers a new policy lens for balancing formal financial expansion and informal debt containment.

Although the coefficients for gender and education appear statistically weak or insignificant in our model, these results reveal an important shift in Thailand’s credit dynamics rather than a lack of effect. Historically, gender and education have been among the strongest predictors of financial inclusion, with studies such as

Coleman (

1999) and

Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (

2013) showing that men and higher-educated individuals are more likely to access formal credit. However, our dataset captures the post-COVID-19 context (2021), when nationwide emergency loan programs and cooperative credit schemes were implemented with relaxed eligibility criteria. These interventions may have temporarily attenuated traditional inequalities by extending credit to groups previously constrained by gender or educational background. In particular, the government’s liquidity support measures—such as low-interest microloans and community-based funds—were widely distributed across demographic groups, reducing variation that might otherwise appear significant. Moreover, the gender-neutral effect may also reflect Thailand’s relatively advanced female participation in financial decision-making and long-standing microfinance penetration in rural communities, which have narrowed gender gaps over time. As for education, the expansion of digital banking, village funds, and nano-finance platforms has enabled even low-educated borrowers to obtain credit, diluting the advantage of higher education noted in pre-pandemic studies. In summary, the apparent insignificance of gender and education in our results likely reflects a temporary equalizing effect of crisis-period policies and widespread financial digitalization, rather than a structural absence of disparity. These patterns suggest that while demographic gaps in access may be narrowing, inequalities in repayment burden, financial literacy, and risk exposure could remain pronounced beneath the surface.

As mentioned earlier in the data section, the present study uses only the 2021 dataset, which was collected during the wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our results may therefore reflect short-term financial stress caused by the pandemic. When additional data become available, future research should investigate long-term financial decisions and indebtedness. Moreover, there are potential omitted variables that could bias our results downward. For example, individuals experiencing health issues during the COVID-19 pandemic may have had a higher likelihood of borrowing money. Due to these limitations, our results should be interpreted cautiously.

Before the pandemic, previous studies found that females, older adults, higher-income (

Hemtanon & Gan, 2020), and educated people (

Coleman, 1999) were more likely to participate in formal microfinance programs. Our results, which cover the pandemic period, are broadly consistent with those findings, except that we do not find significant effects for gender and education on borrowing decisions. This could indicate that the pandemic shock affected all groups equally in their borrowing needs. However,

Hemtanon and Gan (

2020) did not consider informal financial channels, and thus their results are not directly comparable.

Prior to COVID-19, several policies tended to provide agricultural credit directly to farmers. Our results, therefore, unsurprisingly show that farmers are more likely to be formal-sector borrowers. Other groups—such as business owners, employees, and freelancers—may experience difficulty accessing credit and thus rely on informal loans as a quick source of cash, as these require no documents, collateral, or guarantors (

Tanomchat, 2017). During a shock, different household groups may benefit from informal loans in different ways—e.g., asset endowment or consumption (

Kislat, 2015). These flexible borrowing purposes from informal sources explain why they have played an important role in Thailand, particularly during the pandemic and its recovery.

6. Policy Implications

According to our results, the government should pay great attention to farmers in the northern and northeastern regions, as they are more likely to have high levels of formal debt. In general, farmers tend to hold more formal than informal debt, most of which originates from the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives (BAAC). Therefore, the government should work with the BAAC to restructure repayment plans, offer temporary interest-rate reductions during agricultural downturns, and establish targeted debt-relief mechanisms for small-scale farmers. In addition, context-specific financial-literacy programs that combine farm budgeting, risk management, and credit planning could help reduce dependence on repeated borrowing. Such initiatives mirror successful agricultural debt restructuring and training schemes in other emerging economies (e.g., India and Vietnam), suggesting that Thailand could adapt similar institutional models to sustain farmer solvency and productivity.

Civil servants in the northeast also have considerable formal debt. For example, schoolteachers, a major group of civil servants, are known to be heavily indebted through teachers’ savings cooperatives. The government should coordinate with cooperatives, the Ministry of Education, and financial regulators to strengthen supervisory standards, introduce caps on total borrowing relative to income, and ensure transparent disclosure of loan terms and risks. In severe cases, a voluntary debt restructuring or refinancing program for civil servants, coupled with mandatory financial counseling, could be implemented to prevent defaults and maintain household financial stability. This cooperative-based reform aligns with international practices that seek to balance credit access with borrower protection in semi-formal lending systems.

Our analysis indicates that service providers and freelancers, likely concentrated in Bangkok and its periphery, are the group most likely to hold both formal and informal debt. To support these individuals, the government could expand digital-finance solutions such as mobile credit scoring, peer-to-peer (P2P) lending under regulatory sandbox frameworks, and e-payment-based credit histories, while formalizing nano-finance platforms under proper supervision to improve access to affordable credit. Similarly, students, though generally less likely to be indebted, may rely on informal loans when they do borrow and face high repayment burdens. The government and universities could therefore collaborate on low-interest student microloans, income-contingent repayment schemes, and financial mentoring programs to discourage borrowing from informal sources. This approach would parallel youth credit schemes adopted in countries like Malaysia and Indonesia, which aim to promote financial inclusion among younger populations.

Furthermore, the results highlight inequality in access to formal financial institutions. Borrowers using credit cards, commercial banks, and cooperatives are less likely to depend on informal lenders, while those using cash cards, pawnshops, and nano-finance are more likely to hold both formal and informal loans. Thus, the government could consider tightening regulations on pawnshops and informal lenders, including licensing requirements, transparent contract terms, and interest-rate ceilings to protect consumers from predatory practices. At the same time, financial regulators should promote community banking and microfinance institutions in regions heavily reliant on informal credit. This could be achieved by providing incentives for local savings cooperatives and village funds to digitalize, link with national credit databases, and offer capped-interest microloans. Such community-based and technology-enabled financial systems have proven effective in countries like Bangladesh and the Philippines, where they expand inclusion without fostering over-indebtedness.

In sum, to mitigate household over-indebtedness and reduce reliance on informal credit, policies should combine regulation, coordination, and innovation—strengthening oversight of formal lenders, protecting borrowers in the informal market, and expanding safe, accessible, and technology-driven microfinance channels nationwide. The broader relevance of these findings extends beyond Thailand: many emerging economies share similar dual financial structures and social-collateral lending practices. Therefore, the Thai experience provides comparative insights into how integrated microfinance, digital innovation, and borrower protection can together promote sustainable household debt management across developing contexts.