Abstract

As global emphasis on environmental, social, and governance practices intensifies, sustainability reporting emerges as a critical tool for corporate transparency and accountability. The study aims to assess the impact of sustainability reporting on the financial performance of listed companies in Jordan. Using a quantitative approach, a total of 588 individuals were surveyed from low-pollution and high-pollution industries using purposive sampling techniques. Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to conduct analysis of the data with the aid of SMART PLS4 software. The study finds that the impact of sustainability disclosures on firms’ financial performance in Jordan differs significantly by both the type of disclosure and the pollution intensity of the industry the firms belong to. Environmental impact reporting (EIR) and social impact reporting (SIR) both have positive and significant effects on financial performance, especially in low-pollution industries, probably because of a perceived proactive and authentic integration of sustainability practices. However, governance impact reporting (GIR) shows a negative relationship with financial performance, which implies that such disclosures may be perceived as compliance-driven or not authentic. These findings indicate that the context of the sustainability reporting strategy is an important element in determining its effect on financial performance. The multigroup analysis (MGA) results help us to gain a better understanding of how different sectors leverage financial value from disclosing their sustainability activities. The study confirms that sustainability disclosure is not just a compliance requirement, but an instrument that can help firms improve their financial performance. Finally, we recommend that future research should investigate deeper psychological and social mechanisms likely to influence stakeholder responses across different sectors and countries within the region.

1. Introduction

There is growing evidence in the literature of the global focus on corporate sustainability, which has resulted in a considerable increase in sustainability reporting (SR) as businesses seek to disclose their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices (Bosi et al., 2022). Corporate sustainability is defined as the integration of social, environmental, and economic concerns into an organization’s culture, decision-making, strategy, and operations (Meuer et al., 2019). Thus, SR could refer to how corporations disclose information on their ESG performance (Taliento et al., 2019; Bosi et al., 2022; Shaban & Barakat, 2023). It has become an increasingly significant part of corporate transparency as customers, investors, and other relevant stakeholders now seek for more information regarding their firms’ non-financial performance (Saraite-Sariene et al., 2019). SR is a new accounting concept that developed as a result of technological breakthroughs that leave an unparalleled impact on the environment and society in which businesses operate (Maione, 2024).

The current study focuses on financial performance (FP), which measures the monetary outcomes of a company’s strategy, policies, and activities (Boesso et al., 2013). Thus, a firm’s FP has become one of the primary criteria in assessing its success, which is consistent with the aim of enhancing and increasing the possibility of the firms meeting the goal of stakeholders (Ameer & Othman, 2012). The main purpose of this research is to determine how SR can influence the FP of Jordanian companies and to compare them across high-pollution (HP) and low-pollution (LP) industries.

This research is significant and has been emphasized in numerous studies (Shaban & Barakat, 2023). For example, SR enhances the reputation of firms and their brand image (Ul Abideen & Fuling, 2024; Zimon et al., 2022). Similarly, firms can demonstrate their intention of sustainable and ethical business operations by reporting on their ESG impact (Chouaibi et al., 2021; Chouaibi & Affes, 2021). However, the main issue of SR is that it is voluntary and the firms decide what to report, and, in most cases, this is on the positive side to protect a company’s image (Aureli et al., 2020; Hahn & Lülfs, 2014). Therefore, the impact of SR on corporate FP remains a contentious issue in the academic and business community, and this makes it expedient to conduct a study of this nature to understand the global implications of sustainability practices especially among different industries.

Despite the fact that sustainability reporting (SR) has emerged as a worldwide tool of enhancing corporate accountability and transparency, there are still mixed and context-specific empirical findings on the financial implications of sustainability reporting. According to recent research, the connection between the SR and financial performance of firms is affected by various contextual and institutional factors that include regulatory strength, disclosure quality, and industry environmental intensity (Crous et al., 2022; Oncioiu et al., 2020). This implies there is no consensus on whether SR contributes to the better FP of companies or not. Some studies have shown positive relationships while others have not shown any, or have even shown a negative relationship (Aggarwal, 2013; Oncioiu et al., 2020; Reddy & Gordon, 2010; Shaban & Barakat, 2023). Alzeghoul and Alsharari (2025) found that artificial intelligence disclosure improves the financial performance of U.S. banks, but only when it is moderated by governance structures, which highlights the importance of stakeholder alignment and board governance in promoting the value of disclosure. Equally, Monteiro et al. (2024) concluded that there is no significant difference between the financial performance of firms that utilize SR and those that do not in Portugal, indicating that financial benefits are not assured with only the implementation of regulations. The same cannot be said in developing economies. Dincer et al. (2023) demonstrated that SR enhances the short-term accounting performance in Turkish companies, especially within high-impact sectors, whereas Lehenchuk et al. (2023) demonstrated the positive relationship between disclosure of governance-related information and asset turnover in the Turkish food and textile industries only. These discrepancies indicate that there might be industry variations in the SR–financial performance (FP) nexus depending on the intensity of pollution, the intensity of stakeholder scrutiny, and exposure to regulatory pressures.

In addition, current research has thus far concentrated on one country setting (e.g., the U.S. or Portugal) or a particular industry (e.g., banking, energy, or manufacturing), and creates a significant contextual and industry-level gap in comprehending the impacts of SR on FP in a range of industries in emerging markets. Most studies in the Middle East (e.g., Alkasasbeh et al., 2023; Karaki et al., 2023) have focused on macroeconomic relationships between energy, carbon emissions, and growth, but not on the disclosure effect of firms. Therefore, there is minimal information on how industry traits (especially the levels of environmental pollution) affect the SR–FP relationship in the countries where reporting is still voluntary and the institutional control is still developing, as in Jordan. Similarly, there are studies that have focused on the organizational, environmental and sustainability performance of Jordanian manufacturing companies (Albloush et al., 2024; Hussien et al., 2025). To fill this gap, the current study conducts a comparative, multigroup analysis of high- and low-pollution industries, in order to establish whether the effect of SR on FP is different in various environmental settings. In this way, the study helps to improve the theoretical knowledge about the interactions between the stakeholder mechanisms under different industrial and institutional pressures in the developing economies.

Moreover, the study of the high-pollution and low-pollution industrial sectors in Jordan analyzes the relationship between SR and financial outcomes, based on environmental industry characteristics (Xie et al., 2019). Environmental concerns that surround high-pollution sectors create higher external scrutiny, which heightens the financial importance of sustainability disclosure for firms (Lei et al., 2024). The reputation of their businesses, combined with strategic needs, drives low-pollution industries to create sustainability reports. The comparison between these two groups reveals essential details about market characteristics that policymakers, alongside stakeholders, need to adapt their sustainability programs to efficiently.

Based on the foregoing discussion, the study answers the following research questions: Does SR affect the FP of Jordanian firms? Does the impact of SR differ between HP and LP industries? The study is structured as follows: Section 1 is the introduction, while Section 2 reviews the related literature along with other relevant concepts. Section 3 reports the methodology, while Section 4 presents the data analysis and interpretation. Similarly, Section 5 reports conclusions and limitations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Financial Performance (FP)

FP measurement is widely recognized in management accounting as a crucial tool for driving strategic change. Its importance hinges on providing decision-makers with appropriate information to guide them through organizational strategy design, implementation, and review (Pavlatos & Kostakis, 2018). FP has become an important factor in describing a firm’s success, and it is compatible with the aim of improving and raising the likelihood of the firm meeting stakeholder goals (Ameer & Othman, 2012; Gitman et al., 2015). Sreeja et al. (2020) opined that performance can be assessed by its financial outcomes or earnings. Thus, the value of a business is determined by two key factors: riskiness and profitability (Pangestuti et al., 2022). Le Thi Kim et al. (2021) noted that a firm’s FP is also employed as an instrument that gauges the present progress and future growth of an organization. According to Windsor and Boatright (2010), FP can be described as maximizing the owner’s wealth. Schulze and Zellweger (2021) added that organizations focus on creating value to enhance the wealth of their owners.

2.2. Sustainability Reporting (SR)

SR enables companies to describe their ESG policies to investors. The past literature suggests that such reporting is more likely to contain information about the following: the environmental impact of firms, which may include carbon and other greenhouse gas release, as well as water consumption and waste production; the social impact of firms, such as workforce policies, equity initiatives, and community involvement; and their governance practices, which include the board composition and executive remuneration policies (Le et al., 2019). Suhatmi et al. (2024) argue that SR is an important part of corporate strategy, which indicates the increased importance of ESG issues in business. Furthermore, when organizations report on their ESG practices, they signal their long-term strategic priorities, and the aim is to increase stakeholder trust and match global sustainability standards that include the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Maione, 2023; Padilla-Rivera et al., 2025). Thus, companies that make these disclosures inform stakeholders about how they incorporate sustainable development principles into their organizational goals and day-to-day operations (Van Zanten & Van Tulder, 2018).

2.3. Analysis of HP and LP Industries

To better understand the differences in sustainability reporting (SR) practices and financial implications depending on the industry, the studies classify companies as high-pollution (HP) and low-pollution (LP) firms. This comparison brings out the impact of environmental exposure, expectations by the stakeholders and the intensity of the regulatory environment on corporate disclosure behavior. As Table 1 demonstrates, HP industries are more inclined to use sustainability reporting as a legitimacy and risk management tool, whereas LP industries are more strategic in using it to improve brand image and trust among stakeholders. The table outlines the main differences between these two groups in relation to the level of disclosure, purpose of reporting as well as stakeholder engagement, performance indicators and challenges encountered.

Table 1.

Key differences in sustainability reporting practices between high- and low-pollution industries.

2.4. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.4.1. Stakeholder Theory

With the increase in organizational complexity, scholars opined that organizations are no longer dealing with shareholders but with entire stakeholders. This is why the companies are expected to make decisions that would be beneficial to all the stakeholders and not just the shareholders (Ernst et al., 2022; Harrison et al., 2015). According to past research findings, the stakeholder theory provides a realistic, efficient, and ethically based approach to managing organizations in complex and uncertain situations (Richter & Dow, 2017). It is also a practical theory, since every business has to deal with its stakeholders (Orts & Strudler, 2009). However, it remains to be seen whether the firms can manage those complexities or not. Feminist ethics integrated social contracts theory, the principle of the common good, the principle of fairness, and pragmatism are some of the theoretical frameworks that have supported stakeholder theory (Argandoña, 1998; Donaldson & Dunfee, 1995; Freeman et al., 2010; Phillips, 2003; Wicks et al., 1994).

According to the stakeholders’ theory, the role of organizations is not just to provide value for shareholders, but also for all their stakeholders as well (Mrabure & Abhulimhen-Iyoha, 2020). In the current global business world, SR is a strategic tool that enables companies to communicate to their stakeholders regarding ESG performance. SR increases transparency that, in turn, increases trust among stakeholders (customers, investors, regulators, and communities), potentially leading to better reputation and financials (Sari & Muslim, 2024). Sustainably reporting firms that proactively interact with stakeholders are more likely to earn stakeholder trust, and to form stronger ties to the stakeholders, ultimately reaping benefits in the form of reputational rewards and the repayment of the initial financial investment made (Gidage & Bhide, 2024). In Jordan, firms are engaged in different sectors with different footprints. HP industries, such as cement, mining, and energy, attract a lot of attention from stakeholders because of their environmental impact (Al-Msiedeen & Elamer, 2025). There are LP industries (such as banking, IT, and retail) that are not under any immediate pressure from environment, yet they are still involved with stakeholders interested in ethical governance and social responsibility.

Theoretically, this study advances the understanding of the nexus between sustainability reporting and financial performance by using stakeholder theory to explain the heterogeneous effects of sustainability disclosures across industrial contexts. The stakeholder theory assumes that responding to stakeholder expectations improves firms’ value. However, prior studies have largely examined these frameworks in isolation and in developed economies with stringent ESG regulations. Therefore, by applying a multigroup analysis across high- and low-pollution industries in an emerging market like Jordan, this study refines this theory by revealing how the relative importance of stakeholders operates under environmental and regulatory pressures. Thus, the study contributes theoretically by contextualizing and refining classical sustainability theory within a Middle Eastern, voluntary-reporting environment, where institutional pressures, cultural expectations, and industry risk profiles interact to shape the relationship between SR and FP.

2.4.2. Hypothesis Development

SR demonstrates firms’ commitment to sustainable development and accountability to stakeholders. Firms’ reputation and performance are influenced by how they report on their sustainability activities (Sehgal et al., 2023). By revealing its sustainability performance, a company provides both financial and non-financial information, allowing businesses to communicate more clearly with the public about their business operations and other performance metrics (Raucci & Tarquinio, 2020). However, stakeholders understand the significant importance of the FP of the firm, particularly in enhancing its market value (Derun & Mysaka, 2018). Similarly, it is worthwhile noting that examining the determinants of FP has acquired significant pace in the corporate finance literature (Grewatsch & Kleindienst, 2017) because of the diversity and engagement of these organizations in an array of seemingly unconnected business operations that are prone to all forms of risk.

As mentioned earlier, there is still a debate, both in academia and in industry, regarding the effect of SR on the FP of companies, which necessitates the need to analyze the issue thoroughly to comprehend the global consequences of sustainability activities and FP. Das et al. (2024) posited that the stock price and FP of companies that engage in SR are higher than those companies that fail to report on their sustainability practices. This may be as a result of the fact that SR either leads to long-term financial well-being, or minimizes costs and maximizes revenues. However, the voluntary nature of SR poses serious threats to the entire concept. This is because companies choose what and how to disclose, based on their interests. As Okon et al. (2023) clarify, success in sustainability implies having a healthy balance among its dimensions. Thus, the stakeholders can no longer use financial statements because they lack sufficient information on the environment- and social-related processes of the company (Gray et al., 1995).

Another significant challenge is the cost associated with SR, as revealed by many previous studies. For example, Roszkowska-Menkes (2023), reported that the costs associated with sustainability practices, such as carbon reduction programs or waste management improvements, can be significant, prompting corporations to ask if these expenditures provide adequate financial returns. Another effect of the cost-related issues is that smaller companies or those in emerging markets may struggle to commit resources for sustainability practices, putting them at a disadvantage compared to bigger companies with established sustainability infrastructures. Similarly, previous studies have revealed that organizations with strong sustainability policies can gain a competitive edge by improving their risk management, reputation, and operational efficiencies, which could ultimately convert into greater FP (Cantele & Zardini, 2018). However, another gap that has led to further studies on the relationship between SR and FP is that the relationship is complex and frequently influenced by a variety of internal and external factors, including industry type, regulatory environment, and market maturity (Abeysekera, 2022; Chang et al., 2019; Nazari et al., 2015). Based on the foregoing discussion, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H1:

SR has a significant effect on the FP of Jordanian firms.

H1a:

Environmental impact reporting has a significant effect on the FP of Jordanian firms.

H1b:

Social impact reporting has a significant effect on the FP of Jordanian firms.

H1c:

Governance impact reporting has a significant effect on the FP of Jordanian firms.

H2:

There is significant difference between HP and LP industries in terms of the impact of SR on the FP of Jordanian firms.

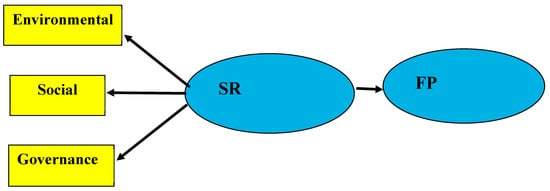

2.4.3. Research Model

The study developed a hypothesized model based on the evidence established in the reviewed extant literature. Thus, the proposed model is presented in Figure 1. The model shows the relationship between SR (independent variable) and FP (dependent variable).

Figure 1.

Proposed model.

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

The study adopts a simple survey method, the most effective approach in social science research, which involves seeking primary data for descriptive purposes (Bhattacherjee, 2012). In terms of the direct relationship, the study evaluates the impact of SR on FP. Similarly, the study used a quantitative and comparative method to examine the impact of SR on the FP of firms in HP and LP industries in Jordan. This method allowed the researcher to test hypotheses using financial and sustainability data while also comparing outcomes across two unique sector groups. There are about 161 listed companies in Jordan as of January 2025, based data from Amman Stock Exchange. Of this number, around 25 firms are in high-pollution industries, while the rest are in low-pollution industries. The high pollution firms are in the following sectors: cement and construction materials, mining and extraction (e.g., potash, phosphate), chemicals and fertilizers, energy (including oil and gas), and metallurgical industries.

However, to gather data, 250 questionnaires were distributed, 10 to each of the twenty-five firms in high-pollution industries, using purposive sampling. Heads of units and departments were chosen as the unit of analysis, as they were deemed to have better knowledge of their companies’ sustainability impact and performance. Similarly, three questionnaires were distributed to each of the 136 firms in low-pollution industries, totaling four hundred and eight questionnaires. Overall, 608 questionnaires were distributed in all the firms. After the data collection, 221 and 367 questionnaires were returned from the HP and LP industries, respectively. This means that 588 questionnaires were used to run the analysis to ascertain if significant differences exist between HP and LP industries in terms of the effect of SR on FP. The study used multigroup analysis (MGA) with the aid of Smart PLS4 software.

3.2. Measurement of Study Variables

The independent variable (SR) is presented as multi-dimensional construct with three sub-dimensions. Thus, SR was measured under environmental impact reporting (EIR, six items), social impact reporting (SIR, six items), and governance impact reporting (GIR, six items) adapted from the Global Reporting Initiative, the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, and the International Sustainability Standards Board. These three organizations are key global bodies involved in sustainability- and climate-related reporting standards. Similarly, FP is presented as a one-dimension construct with five items adapted from Kafetzopoulos et al. (2019). A five-point Likert scale was utilized to measure the items in the questionnaire.

4. Data Analysis

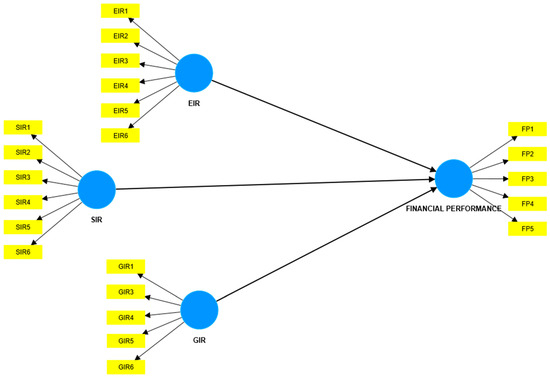

The study employed PLS-SEM, whereby path models were used to interpret the results obtained. Path models visualize the constructs and their hypothesized relationships in cases where SEM is implemented (J. F. Hair et al., 2011). In the path models, latent variables are shown as ovals or circles, whereas indicators which are the direct measured proxy variables that have the raw data are typically presented as rectangles (J. F. J. Hair et al., 2014). PLS path model has two (2) components; the first component is the measurement model and the second component is the structural model (J. F. J. Hair et al., 2014).

4.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

In this section, the findings of measurement model according to conceptualization of the study constructs are presented. Thus, the measurement model evaluation was performed according to some of the basic standards that comprise internal consistency reliabilities, and the convergent and discriminant validity of each of the constructs as proposed by J. F. Hair et al. (2017a) and Henseler et al. (2009). Therefore, Table 2 below indicates the proposed cut-off of the measurement model.

Table 2.

Operationalization of study variables.

4.1.1. Individual Item Reliability

The reliability of all the constructs was examined using the indicators’ outer loadings that measured all constructs (Duarte & Raposo, 2010; J. F. Hair et al., 2017a). J. F. Hair et al. (2017b) state that outer loading indicators must exceed 0.70. However, outer loadings of 0.40 to 0.70 can be deleted if they have the capacity to raise the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE).

Reliability provides an explanation of how the indicators are consistent in the measurement of the construct. Generally, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is used by researchers to test reliability in social and management sciences research. But in the case of PLS-SEM estimation, J. F. J. Hair et al. (2014) suggest the use of the CR coefficient, instead of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, being less biased in PLS-SEM. The CR values of 0.7–0.9 are the most preferable as a criterion in the internal consistency reliability measurement (Kline, 1999). The CR coefficients in this study range between 0.862 and 0.944, above the threshold level of 0.7. Therefore, the reliability of internal consistency in this study is attained. Following J. F. Hair et al. (2017b), only one item (GIR2) was deleted because the loadings fall below the threshold. This can be seen in the figure below.

Figure 2 shows that the measurement model indicates the items’ reliability for all the constructs of the study. This can also be seen in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Measurement model.

Table 3.

Measurement model assessment criteria.

The four latent constructs used are evaluated for validity and reliability in Table 4. Cronbach’s alpha, CR, and AVE are the primary statistical indicators for every construct. To make the constructs internally consistent and appropriate for further analysis, these steps are crucial in structural equation modeling.

Table 4.

Measurement model: reliability and convergent validity (n = 588).

In Table 4, the constructs have Cronbach’s alpha values above the threshold of 0.7, which indicate strong internal consistency between the items that make up each construct. For instance, environmental sustainability has the highest alpha (0.929), signaling a high degree of consistency across its measured indicators. In a similar vein, other constructs are also sufficiently reliable in their measurement. The internal consistency and reliability achieved is further supported by CR values, which are significantly above the suggested 0.7 threshold for all constructs. Since composite reliability does not assume the equal weighting of items, it is generally seen to be a more accurate indicator than Cronbach’s alpha in SEM, as earlier stressed by J. F. J. Hair et al. (2014).

In addition, a metric known as the AVE is another measure of convergent validity which quantifies how much of the variance was explained that can be caused by measurement error. The convergent validity is how far a measure is in positive correlation with substitute measures of the same latent variables (J. F. Hair et al., 2017a). Therefore, AVE is used to establish convergent validity. The AVE value should be greater than 0.5. In this study, therefore, the criterion is met by all constructs, as the values range from 0561 and 0.736. Thus, the reliability of all four constructs is statistically sound, and the measurement model can be considered robust, as evidenced by the high values of all indicators.

4.1.2. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity describes how much a construct is unique concerning other constructs of its model, based on empirical criteria (Duarte & Raposo, 2010; J. F. Hair et al., 2017a). It is primarily assessed by the researchers with the help of the Fornell–Larcker criterion. According to Henseler et al. (2015), the Fornell–Larcker criterion and cross-loading can hardly produce valid discriminant validity and therefore they recommend the HTMT technique as a valid criterion to estimate discriminant validity. Thus, the present research uses the HTMT technique of discriminant validity measurement.

According to Henseler et al. (2015), HTMT is the average of all correlations between indicators across the constructs relative to the geometric mean of the correlations between indicators in the same construct. It is generally the ratio of between-construct (trait) correlations divided by within-construct (trait) correlations. The HTMT approach is a measure of correlation between two constructs under conditions of perfect measurement reliability. The thresholds of the HTMT value required to reach the sufficient discriminant validity are recommended to be 0.85 or 0.90 (J. F. Hair et al., 2017a; Henseler et al., 2015; Kline, 2011). Thus, the following Table 5 shows the HTMT values:

Table 5.

HTMT.

Based on the HTMT criterion, Table 5 shows a value of 0.873 as the highest. In the context of the HTMT technique, a value below 0.85 (or in stricter cases, 0.90) is considered acceptable and indicates that the constructs are empirically distinct. This shows strong discriminant validity. It means that although the constructs are correlated, they are not overlapping in what they measure and are statistically different enough to be treated as separate constructs in the measurement model. If the HTMT value had been greater than 0.90, it would raise concerns about redundancy or poor construct separation.

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

The structural model (inner model) generally specifies the relationships between the constructs. The model was used to test the hypothesis. There are basically four key criteria for evaluating the structural model in PLS-SEM, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Structural model assessment criteria.

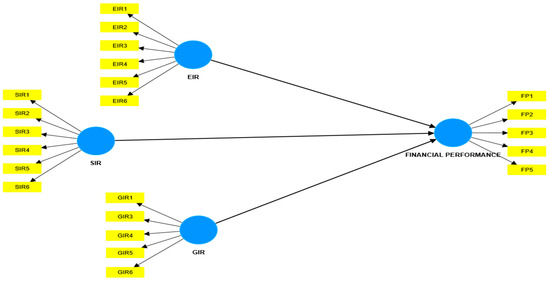

4.2.1. Path Coefficients for the Study Model

Following the satisfaction of the requirements of the reflective measurement model, this section presents the structural model results with which the hypotheses were tested. The standard bootstrapping method of 5000 bootstrap samples of 588 units of data was used to determine the importance of the path coefficients (Sarstedt et al., 2014; J. F. Hair et al., 2017a), as shown in both Table 7 and Figure 3.

Table 7.

Path coefficient for the model.

Figure 3.

PLS bootstrap image.

For the first relationship, the beta value 0.189 means that as environmental impact reporting (EIR) increases, FP increases slightly all things being equal. Then, the p-value 0.000 shows that the relationship is significant at the 5% level (p < 0.05). The high t-value means the effect is not due to chance. The results imply that firms that improve their environmental reporting practices tend to see moderate financial benefits. For the relationship between governance impact reporting and FP, the beta value of −0.106 indicates a negative relationship. It means that an increase in governance impact reporting (GIR) leads to a slight decrease in FP. The t-statistic of 3.203 and p-value of 0.001 show that the relationship is significant, suggesting the negative effect is real. In the context of this study, this means that while governance efforts in SR are important, they may come with costs or complexities that slightly reduce short-term FP, or they may not be well-communicated to produce financial returns.

Lastly, the path coefficient of 0.754 shows a strong positive relationship between social impact reporting and FP. It indicates that a unit increase in social impact reporting (SIR) leads to a 0.754 unit increase in FP. Similarly, the t-statistic 23.746 and p-value 0.000 suggest a highly significant relationship, with strong statistical confidence. The implication of this is that firms that invest in and report on their social initiatives such as community involvement, employee welfare, etc., see the greatest financial benefits. This could be due to improved reputation, stakeholder trust, and employee satisfaction.

4.2.2. Coefficient of Determination for the Model

The coefficient of determination (R2) is used to show the degree to which the variance in the dependent variable is determined by one or more explanatory variable in terms of percentage. (Elliott & Woodward, 2007; J. F. Hair et al., 2010, 2019). The value of R2 is 0 to 1. The closer the R-square is to 1 the greater is the explained variance. However, the appropriate threshold of R2 varies with the field of research. According to Cohen (1988), an R2 value of 0.02, 0.13, and 0.26 are categorized as weak, small, and substantial, respectively. On the other hand, Chin (1998) indicates that the value of the R2 of endogenous latent constructs at 0.67, 0.33, and 0.19 is substantial, moderate, and weak, consecutively.

The R2 value in Table 8 indicates how much of the variance in FP was explained by SR dimensions in the model. Using the benchmarks proposed by both Cohen (1988) and Chin (1998), the value 0.673 means that 67.3% variance in the FP of Jordanian firms was explained by SR variables. However, there is still about 33% unexplained variance, leaving room for additional influencing factors that have not been captured by this study.

Table 8.

Coefficient of determination (R2).

4.2.3. Assessment of the Effect Size for the Relationships

Effect size is an indicator of the highest point of the correlation between two constructs. It is used to determine the relative contribution of an independent variable to a response variable by the change in R2 value (Chin, 1998). The f2 shows how each of the independent variables contributes towards the explanatory ability of the model. According to standard criteria, the f2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 correspond to small, medium, and large effects, respectively (Cohen, 1988). Table 9 shows the corresponding effect sizes of the exogenous variables to the endogenous variables in the model.

Table 9.

Effect size for the model: F-square.

The effect size results, as shown in Table 9, indicate that social impact has the most substantial effect on the model, with a substantial f2 value of 0.904, which shows it plays a dominant role in explaining the variance in FP. This suggests that social dimensions such as community involvement, employee welfare, and social corporate responsibility are essential drivers of FP in the context of the study. Similarly, environmental impact shows a small effect (f2 = 0.065), reflecting a modest contribution to the model, while governance impact has a very small effect (f2 = 0.021), which shows a minimal explanatory power in this context. These findings point to the need for organizations to prioritize social initiatives for their corporate social responsibilities if they aim to significantly improve their FP.

4.3. Multigroup Analysis of Low- and High-Pollution Industries

In this section, a Multigroup Analysis (MGA) is conducted to examine if differences exist in the relationship between SR and FP among firms in HP and LP industries. The analysis aims to reveal whether the impact of SR on FP is substantially contingent on the industry pollution level. This would broaden our understanding of the role of the environmental setting in determining the financial benefits of the environmental practices of companies. The MGA process starts with the specification of the groups with respect to categorical specifications that are relevant and it then estimates the separate PLS path models of each group with the same structural and measurement specifications. The path coefficients and the R2 values are compared after determining the reliability and validity of the constructs in each group. Then, the PLS-MGA algorithm (or Henseler MGA, or the permutation test) is used to test the statistically significant difference between in the relationships of the constructs in different groups. A p-value that is less than 0.05 (or higher than 0.95 in two-tailed tests) is a sign that the effects in the groups are significantly different. Lastly, the findings are discussed to understand how and why relationships differ across situations, and to offer information about how group characteristics moderately affect them (J. F. Hair et al., 2019; Sarstedt et al., 2014). Table 10 presents the MGA results.

Table 10.

Multigroup analysis.

The result for the first relationship shows a negative and significant difference, which means that environmental impact reporting (EIR) has a stronger positive effect (p-value = 0.019) on FP in low-pollution industries in the studied context. In high-pollution sectors, its financial relevance is significantly weaker. The positive but insignificant (p-value = 0.085) difference implies that governance impact reporting (GIR) may have a stronger effect on FP in high-pollution industries, possibly because of high investor expectations or stringent scrutiny by the regulatory authorities. Furthermore, with regard to the relationship between social impact reporting and FP, the negative and significant difference (p-value = 0.034) reveals that social impact reporting (SIR) contributes more strongly to FP in low-pollution industries than in high-pollution ones, where the effect is weaker when compared.

4.4. Discussion of Findings

The results of the structural model show different effects of the three SR dimensions on FP of companies in Jordan. Although all the three relationships are statistically significant, they differ substantially in their direction and strength. The finding reveals a positive and significant relationship between EIR and FP (β = 0.189, p = 0.000), which implies that firms that actively disclose their environmental efforts appear to be more likely to generate financial benefits. Some of those endeavors involve matters of energy efficiency, carbon reduction, and waste management. This finding is consistent with that of other researchers in the past (Das et al., 2024), whose studies confirm the impact of SR on FP. This finding is also consistent with the stakeholder theory, which posits that the environmental performance of firms should be communicated in a transparent manner because such a strategy assists firms to have positive relationships with their stakeholders, which in the long run leads to the better financial performance of the firms. In this manner, the positive and meaningful connection between EIR and FP in this research contributes to the more general perspective that the role of environmental sustainability is not an act of compliance but a strategic force of corporate value-making.

In contrast, we found a negative but significant relationship between GIR and FP (β = −0.106, p = 0.001). This suggests that governance impact reporting may not be a driver for immediate financial benefits for companies but may be perceived, rather, as burdensome. This may imply that the governance impact disclosures are not linked to the actual governance improvements, or that the disclosures are perceived by the interested parties as compliance-based, instead of value-based, improvements. Additionally, some firms may be pretending to have sound governance policies but without effective implementation. This could create skepticism among investors and thus reduce perceived authenticity, thereby affecting the FP of the firms. In emerging markets, such as in Jordan where the governance mechanisms are still in their immature stages and most of the time there is no proper enforcement, companies might engage in governance reporting just to meet the regulatory or reputational demands, but not as a sign of internal governance change. This separation between disclosure and practice can lead investors to question the credibility of governance information, which can dampen its financial impact (Aureli et al., 2020; Hahn & Lülfs, 2014).

Moreover, social impact reporting (SIR) has a positive and significant impact on FP (β = 0.754, p = 0.000). This implies that businesses that actively participate in and publicize their social initiatives (for example, employee diversity, customer care, community development, and employee well-being) derive financial benefits. The robustness of this effect is demonstrated by the incredibly high t-statistic (23.746). This might be a result of rising market and stakeholder expectations for social corporate responsibility, which reward companies that practice social responsibility with increased brand equity, talent retention, and customer loyalty. These results demonstrate how important the social component of sustainability strategy is, as well as how financially significant it is in the modern business environment. This finding supports the findings of Okon et al. (2023).

In addition, the results of the multigroup analysis (MGA) compare the impact of SR dimensions (EIR, GIR, and SIR) on FP across firms in HP and LP industries in the studied context. The results reveal significant differences in how the two groups derive some financial benefits from sustainability practices reporting. The relationship between EIR and FP shows a negative and significant difference (−0.137, p = 0.019). This clearly indicates that environmental reporting has a stronger positive effect in low-pollution industries compared to high-pollution ones. This could be because firms in low-pollution industries are more likely to integrate environmental practices in a more proactive and credible way, which can enhance stakeholder trust and eventually competitive advantage. Conversely, the firms in high-pollution industries can apparently be motivated to respond to environmental reporting by regulatory pressures and are therefore less likely to make financial benefits through such disclosures.

The MGA further shows a positive but insignificant difference (0.313, p = 0.085) between GIR and FP, indicating a higher impact in high-pollution industries. Given the increased regulatory pressure and reputational risks associated with high-pollution industries, this finding implies that governance practices may seem to carry more financial weight. This is since stakeholders and investors closely monitor governance systems for safeguards against operational and environmental risks. This implies that governance could be a leverage point for high-pollution companies to improve FP and reduce negative perceptions through improved compliance and accountability structures.

In high-pollution industries, where environmental and social scandals can quite easily impair company value, the quality of governance is more likely to be taken by investors and regulators as an indicator of risk management capabilities and ethical robustness. Thus, companies that have better governance systems, including the presence of transparent boards, anti-corruption systems, and stakeholder accountability systems, can have greater investor confidence and access to funds, despite the low short-term financial performance. The difference is, however, statistically insignificant, which shows that governance reforms only might not be enough to produce a quantifiable financial benefit unless there is a credible environmental and social performance. This is in line with the stakeholder theory, which holds that stakeholders assess firms as a whole, as opposed to assessing them based on a single aspect of governance information.

5. Conclusions

The results obtained in both structural model and multigroup analysis (MGA) show the different effects of ESG reporting on the FP in the studied context. The results reveal that social impact reporting (SIR) has the most significant predictive power to FP. Thus, we conclude that companies investing in social projects involving the welfare of their employees, equity, and engagement to the community, among other things, are more likely to achieve high FP than companies with low investment in social initiatives. The study concludes that social SR is increasingly becoming more significant in the way stakeholders expect the business to perform, and create better or enhanced business value. In addition, environmental impact reporting (EIR) also has a positive significant impact on FP. However, governance impact reporting (GIR) reveals a negative but significant impact, suggesting that governance impact disclosures do not improve FP except when they are perceived to be authentic.

This study has a number of relevant theoretical implications for the sustainability reporting and corporate performance literature. Firstly, the strong predictive power of social impact reporting (SIR) supports the fundamental assumptions of the stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984) in focusing on establishing long-term financial value by paying attention to the interests and well-being of various groups of stakeholders—employees, communities, and customers. This finding builds on the theory by emphasizing the fact that social initiatives are not only ethicalities but are also strategic resources that can increase legitimacy and trust, and, hence, financial performance. However, the findings for governance impact reporting imply that governance disclosures in isolation might not give any positive returns unless they are perceived to be sincere and substantive by the stakeholders. This result negates the traditional belief in agency theory that an increase in the disclosure of governance always leads to an increase in performance, but it demonstrates that the quality and perceived authenticity of disclosure is a critical boundary condition. Taken together, these findings lead to the development of sustainability reporting theory by highlighting the differentiated routes that ESG dimensions play in financial performance in the emerging market setting, as in the case of Jordan.

Furthermore, the practical implications of these findings indicate that firms’ sustainability strategy must be context-specific. The sustainability practices that are successful in low-pollution industries might not be successful in high-pollution industries. Secondly, policymakers, investors, and regulators should use sector-specific standards and incentives when addressing the ESG disclosure requirements. Thirdly, the findings of the paper support the importance of conducting a multigroup analysis of the SR of companies and thus suggest that future efforts can focus more on examining deeper psychological and social processes that influence stakeholder responses across sectors and or countries. Overall, the study confirms that sustainability is not only an ethical requirement, but it is also a strategic tool that firms can leverage to improve their FP depending on the context of its adoption.

6. Limitations and Future Direction

Although the present study provides useful information on the different effects of SR on FP in HP and LP industries in Jordan, it has a number of limitations. Firstly, the study draws on information reported by the participants themselves, which was obtained through a survey and was likely to be affected by the subjective interpretation of questions by the respondents. Secondly, the present study covered only listed companies in Jordan, and this could affect the generalizability of the findings to unlisted firms in Jordan and other countries with distinct regulatory and socioeconomic factors. Thirdly, although multigroup analysis (MGA) provides an effective comparative structure, it is also a correlational, rather than a causal, analysis, which limits its capability to make conclusive statements regarding the direction of effects. While the limitations do not invalidate the study’s findings, they may influence the reliability and robustness of the conclusions. The reliance on survey data may bring about subjective bias that may lead respondents to overstate their sustainability practices. Also, using only listed Jordanian companies limits the generalizability of the results since the reporting behavior of smaller unlisted companies may differ under less formal governance structures.

Given the above limitations, mixed-method studies comprising both quantitative and qualitative methods would be useful in the future to discover more contextual explanations of the sustainability practices of firms. Future researchers can adopt longitudinal designs to monitor the said effect over time so as to capture the evolving regulatory requirements. Lastly, a comparative study may be conducted in two or more countries or regions to provide greater generalizability and a better understanding of how the quality of national governance or environmental regulations may mediate such relationships.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study. The study employed an anonymous, non-interventional questionnaire survey involving adult participants. The research did not collect any sensitive personal information and strictly adhered to principles of data confidentiality and anonymity.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study is confidential and cannot be disclosed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abeysekera, I. (2022). A framework for sustainability reporting. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 13(6), 1386–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P. (2013). Sustainability reporting and its impact on corporate financial performance: A literature review. Indian Journal of Commerce and Management Studies, 4(3), 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Albloush, A. A. A., Mufleh, J., Mahmoud, A., Bianchi, P., Ayman, A., & Lehyeh, S. A. (2024). Exploring the moderating role of green human resources and green climate: The impact of corporate social responsibility on environmental performance. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 12(2), 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkasasbeh, O. M., Alassuli, A., & Alzghoul, A. (2023). Energy consumption, economic growth and CO2 emissions in Middle East. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 13(1), 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Msiedeen, J. M., & Elamer, A. A. (2025). How green credit policies and climate change practices drive banking financial performance. Business Strategy & Development, 8(1), e70090. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shaer, H., & Zaman, M. (2019). CEO compensation and sustainability reporting assurance: Evidence from the UK. Journal of Business Ethics, 158, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzeghoul, A., & Alsharari, N. M. (2025). Impact of AI disclosure on the financial reporting and performance as evidence from US banks. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, R., & Othman, R. (2012). Sustainability practices and corporate financial performance: A study based on the top global corporations. Journal of Business Ethics, 108, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argandoña, A. (1998). The stakeholder theory and the common good. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aureli, S., Del Baldo, M., Lombardi, R., & Nappo, F. (2020). Nonfinancial reporting regulation and challenges in sustainability disclosure and corporate governance practices. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(6), 2392–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices. Textbooks Collection. Book 3. Available online: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/oa_textbooks/3 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Boesso, G., Kumar, K., & Michelon, G. (2013). Descriptive, instrumental and strategic approaches to corporate social responsibility: Do they drive the financial performance of companies differently? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 26(3), 399–422. [Google Scholar]

- Bosi, M. K., Lajuni, N., Wellfren, A. C., & Lim, T. S. (2022). Sustainability reporting through environmental, social, and governance: A bibliometric review. Sustainability, 14(19), 12071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S., & Zardini, A. (2018). Is sustainability a competitive advantage for small businesses? An empirical analysis of possible mediators in the sustainability–financial performance relationship. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W. F., Amran, A., Iranmanesh, M., & Foroughi, B. (2019). Drivers of sustainability reporting quality: Financial institution perspective. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 35(4), 632–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chouaibi, S., & Affes, H. (2021). The effect of social and ethical practices on environmental disclosure: Evidence from an international ESG data. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 21(7), 1293–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouaibi, S., Rossi, M., Siggia, D., & Chouaibi, J. (2021). Exploring the moderating role of social and ethical practices in the relationship between environmental disclosure and financial performance: Evidence from ESG companies. Sustainability, 14(1), 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, C., Battisti, E., & Leonidou, E. (2022). Non-financial reporting and company financial performance: A systematic literature review and integrated framework. EuroMed Journal of Business, 17(4), 652–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S. K., Khalilur Rahman, M., & Roy, S. (2024). Does ownership type affect sustainability reporting disclosure? Evidence from an emerging market. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 21(1), 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derun, I., & Mysaka, H. (2018). Stakeholder perception of financial performance in corporate reputation formation. Journal of International Studies, 11(3), 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, B., Keskin, A. I., & Dincer, C. (2023). Nexus between sustainability reporting and firm performance: Considering industry groups, accounting, and market measures. Sustainability, 15, 5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T., & Dunfee, T. W. (1995). Integrative social contracts theory: A communitarian conception of economic ethics. Economics & Philosophy, 11(1), 85–112. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, P. A. O., & Raposo, M. L. B. (2010). A PLS model to study brand preference: An application to the mobile phone market. In Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 449–485). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, A. C., & Woodward, W. A. (2007). Statistical analysis quick reference guidebook: With SPSS examples. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, R., Haar, J., Ernst, R., & Haar, J. (2022). Shareholders vs. stakeholders. In From me to we: How shared value can turn companies into engines of change (pp. 41–59). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357495740_From_Me_to_We_How_Shared_Value_Can_Turn_Companies_Into_Engines_of_Change (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, S. (1974). A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika, 61(1), 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidage, M., & Bhide, S. (2024). Corporate reputation as the nexus: Linking moral and social responsibility, green practices, and organizational performance. Corporate Reputation Review, 1–23. Available online: https://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/9ZPYVnXa/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Gitman, L. J., Joehnk, M. D., Smart, S., & Juchau, R. H. (2015). Fundamentals of investing. Pearson Higher Education AU. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative. (n.d.). GRI standards. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Gray, R., Kouhy, R., & Lavers, S. (1995). Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8(2), 47–77. [Google Scholar]

- Grewatsch, S., & Kleindienst, I. (2017). When does it pay to be good? Moderators and mediators in the corporate sustainability–corporate financial performance relationship: A critical review. Journal of Business Ethics, 145, 383–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R., & Lülfs, R. (2014). Legitimizing negative aspects in GRI-oriented sustainability reporting: A qualitative analysis of corporate disclosure strategies. Journal of Business Ethics, 123, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017a). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Thiele, K. O. (2017b). Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(5), 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ortinau, D. J., & Harrison, D. E. (2010). Essentials of marketing research (Vol. 2). McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J. S., Freeman, R. E., & de Abreu, M. C. S. (2015). Stakeholder theory as an ethical approach to effective management: Applying the theory to multiple contexts. Revista Brasileira de Gestão de Negócios, 17(55), 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Hussien, L. F., Alrawashedh, N. H., Deek, A., Alshaketheep, K., Zraqat, O., Al-Awamleh, H. K., & Zureigat, Q. (2025). Corporate governance and energy sector sustainability performance disclosure. International Journal of Energy Sector Management, 19(5), 1234–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRS Foundation. (n.d.). SASB and other ESG frameworks. Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). Available online: https://sasb.ifrs.org/about/sasb-and-other-esg-frameworks (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Kafetzopoulos, D., Psomas, E., & Skalkos, D. (2019). Innovation dimensions and business performance under environmental uncertainty. European Journal of Innovation Management, 23(5), 856–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaki, B. A., Al_kasasbeh, O., Alassuli, A., & Alzghoul, A. (2023). The impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions using the STIRPAT model. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 13(5), 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (1999). Book review: Psychometric theory. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 17(3), 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.-H., Chuc, A. T., & Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. (2019). Financial inclusion and its impact on financial efficiency and sustainability: Empirical evidence from Asia. Borsa Istanbul Review, 19(4), 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehenchuk, S., Zhyhlei, I., Ivashko, O., & Gliszczyński, G. (2023). The impact of sustainability reporting on financial performance: Evidence from Turkish FBT and TCL sectors. Sustainability, 15, 14707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X., Wang, H., Deng, F., Li, S., & Chang, W. (2024). Sustainability through scrutiny: Enhancing transparency in Chinese corporations via environmental audits. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 16, 2451–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Thi Kim, N., Duvernay, D., & Le Thanh, H. (2021). Determinants of financial performance of listed firms manufacturing food products in Vietnam: Regression analysis and Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition analysis. Journal of Economics and Development, 23(3), 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, G. (2023). An energy company’s journey toward standardized sustainability reporting: Addressing governance challenges. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 17(3), 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, G. (2024). Conceptualizing sustainable innovation reporting in the age of technological advancements. In Sustainable innovation reporting and emerging technologies: Promoting accountability through artificial intelligence, blockchain, and the internet of things (pp. 1–13). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Meuer, J., Koelbel, J., & Hoffmann, V. (2019). On the nature of corporate sustainability. Organization & Environment. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, S., Roque, V., & Faria, M. (2024). Does sustainability reporting impact financial performance? Evidence from the largest Portuguese companies. Sustainability, 16, 6448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrabure, K. O., & Abhulimhen-Iyoha, A. (2020). Corporate governance and protection of stakeholders rights and interests. Beijing Law Review, 11, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, J. A., Herremans, I. M., & Warsame, H. A. (2015). Sustainability reporting: External motivators and internal facilitators. Corporate Governance, 15(3), 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okon, L. J., Philip, I. B., & Okpokpo, A. S. (2023). Sustainability reporting and financial performance sustainability reporting and financial performance. AKSU Journal of Administration and Corporate Governance (AKSUJACOG), 3(1), 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Oncioiu, I., Petrescu, A.-G., Bîlcan, F.-R., Petrescu, M., Popescu, D.-M., & Anghel, E. (2020). Corporate sustainability reporting and financial performance. Sustainability, 12(10), 4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orts, E. W., & Strudler, A. (2009). Putting a stake in stakeholder theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Rivera, A., Hannouf, M., Assefa, G., & Gates, I. (2025). Enhancing environmental, social, and governance, performance and reporting through integration of life cycle sustainability assessment framework. Sustainable Development, 33(2), 2975–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestuti, D. C., Muktiyanto, A., & Geraldina, I. (2022). Role of profitability, business risk, and intellectual capital in increasing firm value. Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business, 37(3), 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O., & Kostakis, X. (2018). The impact of top management team characteristics and historical financial performance on strategic management accounting. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 14(4), 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R. (2003). Stakeholder theory and organizational ethics. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Raucci, D., & Tarquinio, L. (2020). Sustainability performance indicators and non-financial information reporting. Evidence from the Italian case. Administrative Sciences, 10(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K., & Gordon, L. (2010). The effect of sustainability reporting on financial performance: An empirical study using listed companies. Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and Sustainability, 6(2), 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, U. H., & Dow, K. E. (2017). Stakeholder theory: A deliberative perspective. Business Ethics: A European Review, 26(4), 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska-Menkes, M. (2023). Porter and Kramer’s (2006) “shared value”. In Encyclopedia of sustainable management (pp. 2621–2626). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Saraite-Sariene, L., Alonso-Cañadas, J., Galán-Valdivieso, F., & Caba-Pérez, C. (2019). Non-financial information versus financial as a key to the stakeholder engagement: A higher education perspective. Sustainability, 12(1), 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, R., & Muslim, M. (2024). Corporate transparency and environmental reporting: Trends and benefits. Amkop Management Accounting Review (AMAR), 4(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Smith, D., Reams, R., & Hair, J. F., Jr. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(1), 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, W., & Zellweger, T. (2021). Property rights, owner-management, and value creation. Academy of Management Review, 46(3), 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, V., Garg, N., & Singh, J. (2023). Impact of sustainability performance & reporting on a firm’s reputation. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 14(1), 228–240. [Google Scholar]

- Shaban, O. S., & Barakat, A. (2023). The impact of sustainability reporting on a company’s financial performance: Evidence from the emerging market. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 12(4), 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeja, L., Swapna, S., & Shwetha, N. (2020). A study on financial performance. Journal of Resource Management and Technology, 11(3), 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Suhatmi, E. C., Dasman, S., Badarisman, D., Nahar, A., & Jaya, A. A. N. A. (2024). Sustainability reporting and its influence on corporate financial performance: A global analysis. The Journal of Academic Science, 1(6), 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taliento, M., Favino, C., & Netti, A. (2019). Impact of environmental, social, and governance information on economic performance: Evidence of a corporate ‘sustainability advantage’from Europe. Sustainability, 11(6), 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. (2017). Final report: Recommendations of the task force on climate-related financial disclosures. Financial Stability Board. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y. M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 48(1), 159–205. [Google Scholar]

- Ul Abideen, Z., & Fuling, H. (2024). Non-financial sustainability reporting and firm reputation. Evidence from Chinese listed companies. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 20(7), 3027–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, J. A., & Van Tulder, R. (2018). Multinational enterprises and the sustainable development goals: An institutional approach to corporate engagement. Journal of International Business Policy, 1(3), 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, A. C., Gilbert, D. R., Jr., & Freeman, R. E. (1994). A feminist reinterpretation of the stakeholder concept. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4, 475–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, D., & Boatright, J. R. (2010). Shareholder wealth maximization. In Finance ethics: Critical issues in theory and practice (pp. 437–455). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L., Chen, C., & Yu, Y. (2019). Dynamic assessment of environmental efficiency in Chinese industry: A multiple DEA model with a Gini criterion approach. Sustainability, 11(8), 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, G., Arianpoor, A., & Salehi, M. (2022). Sustainability reporting and corporate reputation: The moderating effect of CEO opportunistic behavior. Sustainability, 14(3), 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).