Assessing Fiscal Risk: Hidden Structures of Illicit Tobacco Trade Across the European Union

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- identify the socioeconomic, institutional, and demographic dimensions of the phenomenon.

- (b)

- detect common spatial patterns across member states through multivariate analysis techniques.

- (c)

- classify countries with similar risk profiles to facilitate the understanding and targeting of prevention and control policies.

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variables Selection

3.3. Methods

3.3.1. Dimension Reduction: Principal Component Analysis

3.3.2. Hierarchical Clustering for Spatial Classification

3.3.3. Geographic Analysis and Visualization

4. Results

4.1. Fiscal Risk Determinants from Illicit Tobacco Consumption in the EU

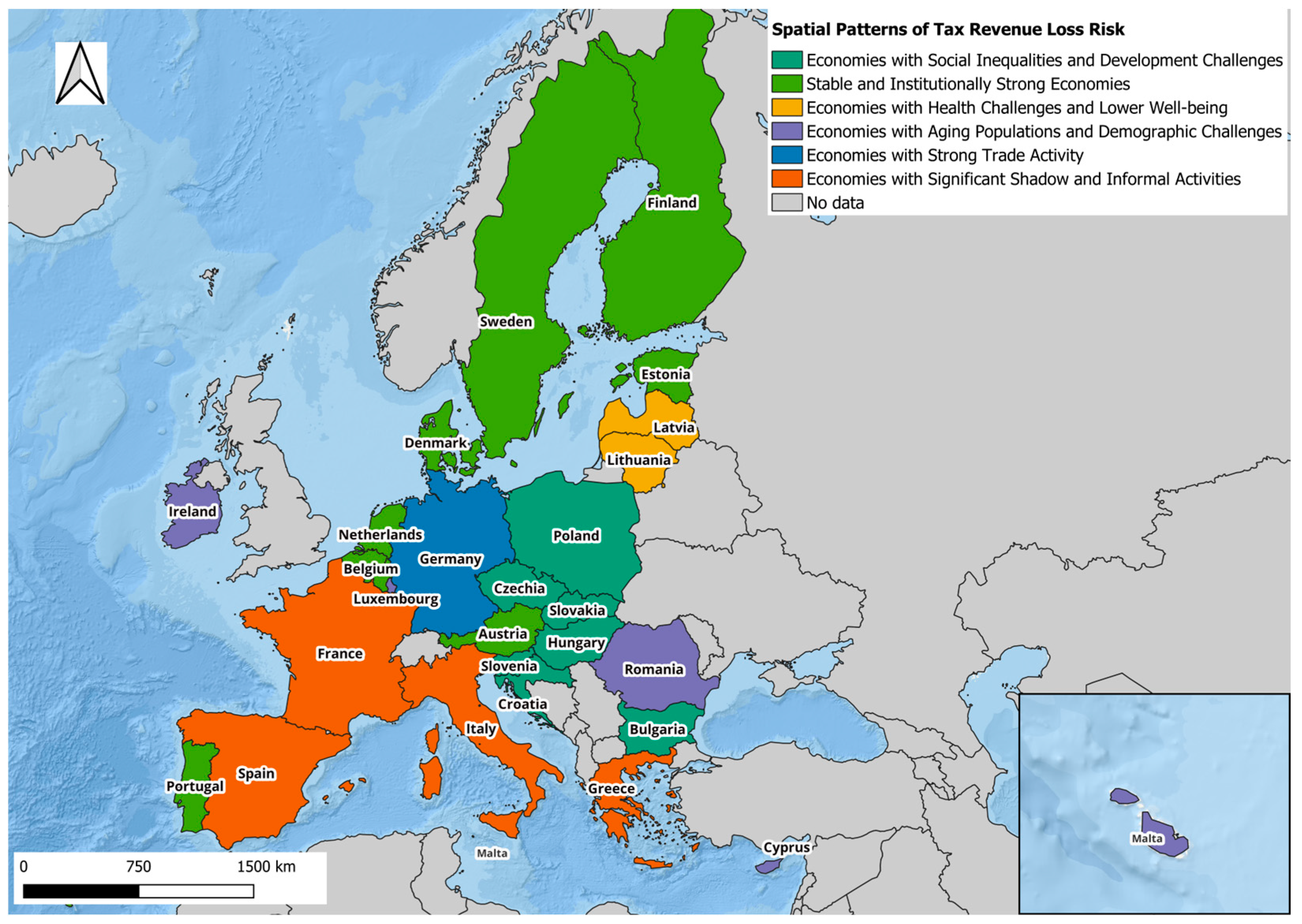

4.2. Spatial Patterns of Tax Revenue Loss Risk

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Overview of Variables and Data Sources

| Variable Name | Definition/Description | Data Source |

| Corruption Index | Perceived levels of public sector corruption (higher values = lower corruption). | Transparency International—Corruption Perceptions Index |

| Rule of Law | Extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society. | World Bank—Worldwide Governance Indicators |

| Government Effectiveness | Quality of public services and policy implementation capacity. | World Bank—Worldwide Governance Indicators |

| Regulatory Quality | Ability of the government to formulate and implement sound regulations. | World Bank—Worldwide Governance Indicators |

| Health Care Expenditure | General government expenditure on health as % of GDP. | Eurostat—Government expenditure by function (COFOG) |

| Real GDP per capita | GDP per capita in constant 2015 prices (EUR). | Eurostat—nama_10_pc |

| Private Sector Debt | Total financial liabilities of the private sector as % of GDP. | Eurostat—gov_10q_ggdebt |

| Urban Population Rate | Share of population living in urban areas. | World Bank—World Development Indicators |

| Environmental Taxes | Total environmental taxes as % of total tax revenue. | Eurostat—env_ac_tax |

| Education Index | Composite index of mean and expected years of schooling. | UNDP—Human Development Report |

| Extra-EU27 Exports | Exports of goods outside EU-27 (EUR million). | Eurostat—ext_lt_intratrd |

| Intra-EU27 Imports | Imports of goods within EU-27 (EUR million). | Eurostat—ext_lt_intratrd |

| Intra-EU27 Exports | Exports of goods within EU-27 (EUR million). | Eurostat—ext_lt_intratrd |

| Extra-EU27 Imports | Imports of goods outside EU-27 (EUR million). | Eurostat—ext_lt_intratrd |

| Population | Total resident population (thousands). | Eurostat—demo_gind |

| Consumption of Fine Cut Tobacco | Quantity of fine-cut tobacco consumed (kg per capita). | European Commission—DG TAXUD/KPMG Project SUN |

| Consumption of Cigarettes | Number of cigarettes consumed (per adult per year). | European Commission—DG TAXUD/KPMG Project SUN |

| Net Migration | Net migration = immigrants − emigrants (per 1000 inhabitants). | Eurostat—demo_gind |

| Total Tax Revenue Lost from Illicit Tobacco Consumption | Estimated annual fiscal loss from illicit tobacco consumption (% of total tobacco tax revenue). | KPMG—Project SUN Report (Commissioned by EC DG TAXUD) |

| Specific Excise to Total Tax Revenue | Share of specific excise duties in total tax revenue from tobacco. | European Commission—Excise Duty Tables |

| Income Distribution | Gini coefficient (0 = perfect equality, 100 = perfect inequality). | Eurostat—ilc_di12 |

| Specific Excise to GDP | Excise duty revenues on tobacco as % of GDP. | European Commission—Excise Duty Tables |

| Poverty Rate | Share of population at risk of poverty (%). | Eurostat—ilc_peps01 |

| SDG Index | Composite index of progress toward Sustainable Development Goals. | UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network |

| Deaths by Neoplasm | Standardized death rate from neoplasms (per 100,000 inhabitants). | Eurostat—hlth_cd_asdr2 |

| Share of Perceived Health | Population reporting good or very good health (%). | Eurostat—hlth_silc_10 |

| Sex Ratio | Male-to-female population ratio (per 100 females). | Eurostat—demo_pjan |

| Crude Death Rate | Number of deaths per 1000 inhabitants. | Eurostat—demo_gind |

| Good Health and Well-Being (SDG3) | Progress indicator for SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being). | UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network |

| Old-Age Dependency Ratio | Ratio of people aged 65+ to those aged 15–64 (%). | Eurostat—demo_pjanind |

| Median Age | Median age of population (years). | Eurostat—demo_pjanind |

| Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG12) | Progress indicator for SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). | UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network |

| Crude Marriage Rate | Number of marriages per 1000 inhabitants. | Eurostat—demo_nind |

| Fiscal Balance | General government net lending (+)/borrowing (–) (% of GDP). | Eurostat—gov_10dd_edpt1 |

| Total Tax to WAP | Total tax burden on weighted average price (WAP) of cigarettes (%). | European Commission—Excise Duty Tables |

| Minimum Excise Duty | Minimum excise duty per 1000 cigarettes (EUR). | European Commission—Excise Duty Tables |

| Specific Excise WAP | Specific excise component of the WAP of cigarettes (%). | European Commission—Excise Duty Tables |

| Unemployment Rate | Share of labor force unemployed (%). | Eurostat—lfsi_emp_a |

| Share of Illicit Cigarette Consumption | Proportion of illicit cigarettes in total consumption (%). | KPMG—Project SUN Report/DG TAXUD |

| Household Saving Rate | Gross household saving as % of gross disposable income. | Eurostat—nama_10_h_bs |

References

- Bhagwati, J. N., & Srinivasan, T. N. (1974). Smuggling and trade policy. In J. N. Bhagwati (Ed.), Illegal transactions in international trade (pp. 27–38). North-Holland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Preventing and reducing illicit tobacco trade in the United States: Executive summary. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/pdfs/illicit-trade-report-508.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Chaloupka, F. J. (2017). Cigarette smuggling in response to large tax increase is greatly exaggerated. Tobacconomics Research Brief, University of Illinois Chicago. Available online: https://www.economicsforhealth.org/uploads/misc/2017/11/2017-generic-smuggling-report.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Clemente, F., & Lírio, V. S. (2018). Institutions and tax evasion level across countries. In Compendium—Cuadernos de economia y administración (Vol. 12, 20p). Compenduim Press. [Google Scholar]

- Closs-Davies, S. C., Bartels, K. P. R., & Merkl-Davies, D. M. (2024). How tax administration influences social justice: The relational power of accounting technologies. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 100, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, N. (2022). Neoliberal social justice and taxation. Social Philosophy and Policy, 39(1), 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCicca, P., Kenkel, D., & Lovenheim, M. F. (2022). The economics of tobacco regulation: A comprehensive review. Journal of Economic Literature, 60(3), 883–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF). (2024). Protecting EU revenue: Fighting tobacco smuggling. In The OLAF report 2024. European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/olaf-report/2024/investigative-activities/protecting-eu-revenue/dealing-with-smuggling_en.html (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- European Commission. (2016). Special Eurobarometer 443: Public perception of illicit tobacco trade. OLAF—European Anti-Fraud Office. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2076 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- European Commission. (2019). Special Eurobarometer 482: Public perception of illicit tobacco trade. OLAF—European Anti-Fraud Office. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2191 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- European Commission. (2020). Commission staff working document: Evaluation of the 2011/64/EU council directive on the structure and rates of excise duty applied to manufactured tobacco (SWD 2020 33 final). Available online: https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-02/10-02-2020-tobacco-taxation-report.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- European Commission Taxation and Customs. (2025a). Excise duties on tobacco. Taxation and Customs Union. Available online: https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/taxation/excise-taxes/excise-duties-tobacco_en (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- European Commission Taxation and Customs. (2025b). Taxes in Europe database v4. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/tedb/#/advanced-search (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. (2011). Council Directive 2011/64/EU of 21 June 2011 on the structure and rates of excise duty applied to manufactured tobacco. Official Journal of the European Union, L176/24. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32011L0064 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Europol. (2022). Criminal networks in EU ports: Risks and challenges for law enforcement [Joint analysis report]. Europol. Available online: https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/Europol_Joint-report_Criminal%20networks%20in%20EU%20ports_Public_version.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Ferdi. (2022). Taxation and the environment: An overview of key issues for tax and environment reform in developing countries. Available online: https://ferdi.fr/dl/df-kg6okxyJB2PFfrxT2HJzuxRt/booklet-taxation-and-the-environment-an-overview-of-key-issues-for.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Gallus, S., Lugo, A., Ghislandi, S., La Vecchia, C., Gilmore, A. B., & Joossens, L. (2014). Illicit cigarettes and hand-rolled tobacco in 18 European countries: A cross-sectional survey. Tobacco Control, 23(e1), e17–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A. B., Rowell, A., Gallus, S., Lugo, A., & Joossens, L. (2014). Towards a greater understanding of the illicit tobacco trade in Europe: A review of the PMI funded ‘Project Star’ report. Tobacco Control, 23(e1), e51–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. (2021). The global illicit economy: Trajectories of transnational organized crime (Report). Global Initiative. Available online: https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/The-Global-Illicit-Economy-GITOC-Low.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- GLOBSEC. (2022). Under the shadows of war in Ukraine: Illicit trade (Report). GLOBSEC. Available online: https://www.globsec.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/Under%20the%20Shadows%20of%20War%20in%20Ukraine%20-%20Illicit%20Trade%20ver2%20spreads.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Goodchild, M., Paul, J., Iglesias, R., Bouw, A., & Perucic, A.-M. (2022). Potential impact of eliminating illicit trade in cigarettes: A demand-side perspective. Tobacco Control, 31(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffer, A., & Macumber-Rosin, J. (2025). The future of EU tobacco taxation: Insights from Member States and best practices for the next Tobacco Excise Tax Directive (Report No. FF859). Tax Foundation. Available online: https://taxfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/FF859.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Ireland, R. (2023). Quantifying the illicit trade in tobacco: A matter of public interest and self-interest. In WCO News (89). World Customs Organization. Available online: https://mag.wcoomd.org/magazine/wco-news-89/profile-enhancing-customs-risk-management/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Jackson, S. E., Cox, S., & Brown, J. (2024). Trends in cross-border and illicit tobacco purchases among people who smoke in England, 2019–2022. Tobacco Control, 33(5), 688–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joossens, L. (2011). Illicit tobacco trade in Europe: Issues and solutions (With a special focus on the tracking and tracing systems) (Deliverable 5.2). PPACTE Project—Work Package 5. Available online: https://www.tri.ie/uploads/3/1/3/6/31366051/industry_and_market_response_ppacte_wp5.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Kamm, A., Koch, C., & Nikiforakis, N. (2021). The ghost of institutions past: History as an obstacle to fighting tax evasion? European Economic Review, 132, 103641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. (2025). Illicit cigarette consumption in Europe: Results for the calendar year 2024. Commissioned by Philip Morris Products SA. Available online: https://www.pmi.com/resources/docs/default-source/itp/illicit-cigarette-consumption-in-europe-2024-results.pdf?sfvrsn=4ad3ac8_6 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Krylova, Y. (2024). The impact of Russia’s full-scale invasion on illicit cigarette trafficking from Ukraine to the European Union. Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, 6(2), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupatadze, A. (2021). Corruption and illicit tobacco trade. Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, 3(1), 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencucha, R., & Callard, C. (2011). Lost revenue estimates from the illicit trade of cigarettes: A 12-country analysis. Tobacco Control, 20(4), 318–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Nicolás, Á. (2023). Tobacco taxes in the European Union: An evaluation of the effects of the european commission’s proposals for a new tobacco tax directive on the markets for cigarettes and fine cut tobacco [Tobacconomics Working Paper]. Tobacconomics. Available online: https://www.economicsforhealth.org/files/research/869/working-paper-tobacco-taxes-eu-final-version-oct-2.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Maclean, J. C., Kessler, A. S., & Kenkel, D. S. (2015). Cigarette taxes and older adult smoking: Evidence from the health and retirement study (Working Paper No. DETU_15_02). Department of Economics, Temple University. Available online: https://www.cla.temple.edu/RePEc/documents/DETU_15_02.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Merriman, D., Yurekli, A., & Chaloupka, F. J. (2000). How big is the worldwide cigarette smuggling problem. In P. Jha, & F. J. Chaloupka (Eds.), Tobacco control in developing countries (pp. 365–392). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mugosa, A., Cizmovic, M., & Vulovic, V. (2024). Impact of tobacco spending on intrahousehold resource allocation in Montenegro. Tobacco Control, 33, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagelhout, G. E., van den Putte, B., Allwright, S., Mons, U., McNeill, A., Guignard, R., Beck, F., Siahpush, M., Joossens, L., Fong, G. T., de Vries, H., & Willemsen, M. C. (2014). Socioeconomic and country variations in cross-border cigarette purchasing as tobacco tax avoidance strategy. Tobacco Control, 23, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. (2016). Health at a Glance: Europe 2016: State of health in the EU cycle. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2020). Revenue statistics 2020. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2024). Consumption tax trends 2024. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/11/consumption-tax-trends-2024_57c7322a/dcd4dd36-en.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- OECD & EUIPO. (2024). Illicit trade in fakes under the COVID-19, illicit trade. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieger, J. E., & Kulick, J. (2018). Cigarette taxes and illicit trade in Europe. Economics for Health. Available online: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1176&context=faculty_pubs (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Primorac, M., & Vlah Jerić, S. (2017). The structure of cigarette excises in the EU: From myths to reality (CESifo Working Paper No. 6386). Center for Economic Studies & ifo Institute. Available online: https://www.ifo.de/DocDL/cesifo1_wp6386.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Remeikienė, R., Gasparėnienė, L., & Raistenskis, E. (2020, April 23–24). Assessing the links between cigarette smuggling and corruption in non-European countries [Conference paper]. Contemporary Issues in Theory and Practice of Management (CITPM 2020), Częstochowa, Poland. Available online: https://www.tf.vu.lt/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Konferencijos-pranesimas_-Links_between_corruption_and_quality_of_life_in_European_Union-pdf.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Ross, H., & Blecher, E. (2019). Illicit trade in tobacco products need not hinder tobacco tax policy reforms and increases (White Paper). Tobacconomics. Available online: https://www.economicsforhealth.org/uploads/misc/2019/11/Illicit-Tobacco-White-Paper_v1.5-2.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Sinn, H.-W. (2018). The link between illicit tobacco trade and organised crime (Speech transcript, PDF). European Economic and Social Committee. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/files/mr_arndt_sinn_speech.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Stoklosa, M. (2020). Prices and cross-border cigarette purchases in the EU: Evidence from demand modelling. Tobacco Control, 29(1), 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoklosa, M., Paraje, G., & Blecher, E. (2020). A toolkit on measuring illicit trade in tobacco products. A tobacconomics and american cancer society toolkit. Tobacconomics, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester, A. L. (2025). The alchemy of sin: Turning tobacco sin tax revenue into public health gold. Lewis & Clark Law Review, 28(4), 863–894. [Google Scholar]

- Tax Foundation. (2023). Cigarette taxes in Europe, 2023. Available online: https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/eu/cigarette-tax-europe-2023/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Tax Foundation. (2024). Cigarette taxes in Europe, 2024. Available online: https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/eu/cigarette-taxes-europe-2024/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- TRACIT. (2019). Illicit trade and the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs). Available online: https://www.tracit.org/uploads/1/0/2/2/102238034/tracit_sdg_july2019_highres.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- U.S. National Cancer Institute & World Health Organization. (2016). The economics of tobacco and tobacco control. National cancer institute tobacco control monograph 21 (NIH Publication No. 16-CA-8029A). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; World Health Organization; NIH Publication. Available online: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/monograph-21 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Valiente, R., Tunstall, H., Kong, A. Y., Wilson, L. B., Gillespie, D., Angus, C., Brennan, A., Shortt, N. K., & Pearce, J. (2024). Geographical differences in the financial impacts of different forms of tobacco licence fees on small retailers in Scotland. Tobacco Control, 34, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable Name | Mean | Median | Std. Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corruption Index | 63.8 | 60.0 | 13.9 | 42.0 | 90.0 | 21.8 |

| Rule of Law | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 13.5 |

| Government Effectiveness | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.6 | −0.3 | 2.0 | 55.6 |

| Regulatory Quality | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 42.9 |

| Health Care Expenditure | 2845.1 | 2302.3 | 1777.8 | 493.8 | 6590.2 | 62.5 |

| Real GDP per capita | 27,666.1 | 22,400.0 | 17,692.6 | 6120.0 | 86,540.0 | 64.0 |

| Private Sector Debt | 156.2 | 125.5 | 80.8 | 44.7 | 414.4 | 51.7 |

| Urban Population Rate | 73.7 | 71.8 | 12.9 | 53.7 | 98.2 | 17.6 |

| Environmental Taxes | 7.0 | 6.8 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 15.3 | 29.9 |

| Education Index | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 6.9 |

| Extra-EU27 Exports | 3.7 | 1.2 | 6.1 | 0.1 | 31.0 | 163.8 |

| Intra-EU27 Imports | 3.7 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 0.1 | 23.2 | 130.4 |

| Intra-EU27 Exports | 3.7 | 1.7 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 23.4 | 134.8 |

| Extra-EU27 Imports | 3.7 | 1.4 | 5.3 | 0.1 | 22.0 | 143.3 |

| Population | 16,511,133.7 | 8,879,919.5 | 21,898,216.1 | 459,375.0 | 83,237,124.0 | 132.6 |

| Consumption of Fine Cut Tobacco | 15,706,623.5 | 7,134,405.5 | 19,442,264.7 | 467,121.0 | 75,837,781.0 | 123.8 |

| Consumption of Cigarettes | 2,794,624.2 | 498,366.0 | 4,994,610.8 | 30,255.0 | 26,328,000.0 | 178.7 |

| Net Migration | 65,933.4 | 21,913.0 | 153,640.0 | −64,758.0 | 1,538,205.0 | 233.0 |

| Total Tax Revenue Lost from Illicit Tobacco Consumption | 327.3 | 83.0 | 877.7 | 0.4 | 7.255.0 | 268.1 |

| Specific Excise to Total Tax Revenue | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 7.8 | 63.6 |

| Income Distribution | 4.8 | 4.4 | 1.2 | 3.0 | 8.2 | 24.1 |

| Specific Excise to GDP | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 2.3 | 53.0 |

| Poverty Rate | 21.2 | 19.9 | 5.9 | 10.7 | 42.5 | 27.8 |

| SDG Index | 69.9 | 69.7 | 5.7 | 54.7 | 81.2 | 8.2 |

| Deaths by Neoplasm | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 15.6 |

| Share of Perceived Health | 67.4 | 68.6 | 9.4 | 43.9 | 84.1 | 14.0 |

| Sex Ratio | 104.9 | 104.4 | 4.9 | 92.3 | 117.7 | 4.7 |

| Crude Death Rate | 11.1 | 10.6 | 2.9 | 6.2 | 22.9 | 26.1 |

| Good Health and Well-Being (SDG3) | 79.5 | 80.4 | 6.8 | 63.7 | 91.0 | 8.5 |

| Old-Age Dependency Ratio | 30.1 | 30.5 | 4.2 | 20.5 | 37.5 | 13.9 |

| Median Age | 42.7 | 42.7 | 2.3 | 36.9 | 48.0 | 5.5 |

| Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG12) | 51.2 | 53.1 | 9.6 | 22.9 | 70.2 | 18.7 |

| Crude Marriage Rate | 4.6 | 4.5 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 8.9 | 29.5 |

| Fiscal Balance | −14,563.2 | −1603.6 | 38,699.4 | −208,236.2 | 65,623.0 | 265.7 |

| Total Tax to WAP | 80.1 | 79.6 | 5.7 | 68.1 | 108.4 | 7.1 |

| Minimum Excise Duty | 62.5 | 61.9 | 5.3 | 50.9 | 88.4 | 8.5 |

| Specific Excise WAP | 35.1 | 36.9 | 15.5 | 8.1 | 87.4 | 44.0 |

| Unemployment Rate | 6.7 | 6.1 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 21.8 | 49.5 |

| Share of Illicit Cigarette Consumption | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 74.1 |

| Household Saving Rate | 10.9 | 11.5 | 6.2 | −6.0 | 25.7 | 57.1 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | Institutional and Economic Stability | International Trade and Market Share | Socio-Economic Inequality and Tax Burdens | Health and Well-Being | Demographic Aging and Social Dynamics | Tobacco Taxation Policy | Labor Dynamics and Shadow Consumption | |

| Corruption Index | 0.921 | 0.900 | ||||||

| Rule of LAW | 0.893 | 0.884 | ||||||

| Government Effectiveness | 0.932 | 0.878 | ||||||

| Regulatory Quality | 0.900 | 0.876 | ||||||

| Health Care Expenditure | 0.922 | 0.822 | ||||||

| Real GDP per capita | 0.862 | 0.739 | ||||||

| Private sector debt | 0.889 | 0.653 | ||||||

| Urban Population Rate | 0.632 | 0.642 | ||||||

| Environmental Taxes | 0.689 | −0.532 | ||||||

| Education Index | 0.675 | 0.523 | ||||||

| Extra-EU27 Exports | 0.957 | 0.948 | ||||||

| Intra-EU27 Imports | 0.975 | 0.947 | ||||||

| Intra-EU27 Exports | 0.957 | 0.934 | ||||||

| Extra-EU27 Imports | 0.957 | 0.910 | ||||||

| Population | 0.947 | 0.907 | ||||||

| Consumption of fine cut tobacco | 0.892 | 0.906 | ||||||

| Consumption of Cigarettes | 0.892 | 0.850 | ||||||

| Net migration | 0.768 | 0.780 | ||||||

| Total tax revenue lost from illicit tobacco consumption | 0.805 | 0.763 | ||||||

| Specific excise to total tax revenue | 0.914 | 0.806 | ||||||

| Income distribution | 0.902 | 0.765 | ||||||

| Specific excise to GDP | 0.885 | 0.706 | ||||||

| Poverty rate | 0.877 | −0.650 | ||||||

| SDG | 0.869 | 0.644 | ||||||

| Deaths by Neoplasm | 0.694 | −0.620 | ||||||

| Share of perceived health | 0.806 | 0.868 | ||||||

| Sex ratio | 0.832 | −0.824 | ||||||

| Crude death rate | 0.898 | −0.623 | ||||||

| Good health and well-being (SDG3) | 0.946 | 0.609 | ||||||

| Old-age dependency ratio | 0.822 | 0.733 | ||||||

| Median age | 0.856 | 0.696 | ||||||

| Responsible consumption and production Indicator (SDG12) | 0.690 | 0.653 | ||||||

| Crude marriage rate | 0.635 | −0.604 | ||||||

| Fiscal Balance | 0.468 | −0.489 | ||||||

| Total tax to WAP | 0.842 | 0.826 | ||||||

| Minimum excise duty | 0.741 | 0.805 | ||||||

| Specific Excise WAP | 0.585 | 0.652 | ||||||

| Unemployment rate | 0.806 | 0.803 | ||||||

| Share of illicit cigarette consumption | 0.788 | 0.639 | ||||||

| Household saving rate | 0.626 | −0.483 | ||||||

| Total Variance Explained (%) | 32.426 | 20.382 | 8.591 | 6.511 | 5.553 | 4.859 | 3.938 |

| Spatial Patterns | Risk of Tax Loss (%) | Member States | Institutional and Economic Stability | International Trade and Market Share | Socio-Economic Inequality and Tax Burdens | Health and Well-Being | Demographic Aging and Social Dynamics | Tobacco Taxation Policy | Labor Dynamics and Shadow Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable and Institutionally Strong Economies | 9.8 | Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden | ++ | — | — | ᴑ | + | + | — |

| Economies with Social Inequalities and Development Challenges | 9.1 | Croatia, Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria | —— | — | —— | — | ᴑ | ᴑ | —— |

| Economies with Aging Populations and Demographic Challenges | 23.2 | Cyprus, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, Romania | ᴑ | — | + | + | —— | — | + |

| Economies with Strong Trade Activity | 25.6 | Germany | ++ | ++ | + | — | — | — | — |

| Economies with Significant Shadow and Informal Activities | 55 | Greece, Italy, Spain, France | — | + | + | + | ++ | — | ++ |

| Economies with Health Challenges and Lower Well-being | 11.8 | Latvia, Lithuania | + | — | + | —— | — | + | ++ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anastasiou, E.; Theodossiou, G.; Koutoupis, A.; Manika, S.; Karalidis, K. Assessing Fiscal Risk: Hidden Structures of Illicit Tobacco Trade Across the European Union. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110611

Anastasiou E, Theodossiou G, Koutoupis A, Manika S, Karalidis K. Assessing Fiscal Risk: Hidden Structures of Illicit Tobacco Trade Across the European Union. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(11):611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110611

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnastasiou, Evgenia, George Theodossiou, Andreas Koutoupis, Stella Manika, and Konstantinos Karalidis. 2025. "Assessing Fiscal Risk: Hidden Structures of Illicit Tobacco Trade Across the European Union" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 11: 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110611

APA StyleAnastasiou, E., Theodossiou, G., Koutoupis, A., Manika, S., & Karalidis, K. (2025). Assessing Fiscal Risk: Hidden Structures of Illicit Tobacco Trade Across the European Union. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(11), 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110611