1. Introduction

The initial public offering of Circle Internet Group, Inc. (NYSE: CRCL) was one of the most successful IPOs in recent history. Circle offered 34 million shares at

$31.00 share, giving the company an implied valuation of

$6.8 Billion (

Biswas & Saini, 2025). After trading began on 5 June 2025 CRCL shares surged to

$120 within the first week, and then rallied onward to

$299 within three weeks, reaching an all-time-high valuation at an implied firm value of more than

$65 Billion on 23 June 2025, almost ten times higher than where it had been priced only nineteen days prior (

Hamid, 2025). Although the share price soon pulled back, this high-water mark was very impressive, especially considering the fact that on 23 June, Circle’s market capitalization exceeded the market capitalization of its flagship stablecoin, USDC, by several billion dollars (

Coingecko, 2025). Many pundits (

Gelsi, 2025) observed that Circle’s bull run had gone too far, that the firm, whose only significant source of revenue is the net interest margin it earns on its reserve assets, could not be worth more than its own stablecoin’s capitalization.

Although the valuation of Circle is not the topic of this paper, the volatility of its post-IPO valuation clearly indicates that there is substantial difference of opinion among market participants regarding Circle’s valuation, and consequently, of the valuation of the entire stablecoin industry moving forward. Now that the

GENIUS Act (

2025) has been signed into law, many (

Nyarunda, 2025) are expecting the stablecoin industry to grow substantially, and not everyone is pleased by the prospect. In its April 30 presentation, the

U.S. Department of the Treasury (

2025) estimated that growth in stablecoins could lead to

$6.6 Trillion in deposit outflows from banks. In an 12 August article, the Bank Policy Institute (BPI) called for Congress to eliminate a loophole in the GENIUS Act, arguing that by allowing Stablecoin Issuers to indirectly pay interest to stablecoin holders, the Act further encourages capital flight out of bank deposits and threatens to impede the flow of credit to households and businesses (2025).

In this paper we argue that BPI’s concerns are unfounded. We first provide an industry-level prognostic analysis of Stablecoin Issuance as regulated under the GENIUS Act. We begin with an analysis of the likely profit margin that Stablecoin Issuers (Issuers) can expect to generate at various scales of business. This will require a discussion of the revenue prospects of Issuers, as well as an analysis of the likely expenses that any Issuer will incur. To do this will require a detailed discussion of the regulatory requirements put forth in the GENIUS Act as well as the established business practices of various Stablecoin Issuers. Finally, we analyze the interest loophole, its effect on Issuer profitability, and the economic forces it brings to bear on the stablecoin industry as a whole. Our analysis suggests that, rather than threatening to drain liquidity from banks, the interest loophole has the paradoxical effect of making banks even more competitive in the stablecoin industry, potentially allowing them not only to replace lost deposits with stablecoin reserves but also generate profits from issuing and distributing stablecoins.

2. Issuer Revenue

The revenue prospects for Stablecoin Issuers are simple: they are a function of the expected yield on stablecoin reserves. Under the

GENIUS Act (

2025), Issuers must keep at least

$1 in assets to back every

$1 in stablecoins issued. Issuers may keep reserves in Federal Reserve Notes, a U.S. Bank Account, the Federal Reserve’s Repo Facility, Money Market Funds (MMFs), or U.S. Treasury Bonds, Notes, and Bills with a maturity of 93 days or fewer. Any yield generated by these assets is revenue for the Issuer, and Stablecoin Issuers are prohibited from directly sharing this yield with stablecoin holders.

It is important to note that the

GENIUS Act (

2025) only explicitly applies to “Payment Stablecoins,” so defined as digital assets, the Issuer of which is, “obligated to convert, redeem, or repurchase for a fixed amount of monetary value.” The

GENIUS Act (

2025) explicitly defines “Monetary Value” as a national currency, or a deposit denominated in a national currency, so only stablecoins that are redeemable for U.S. Dollars or Dollar-denominated deposits in a financial institution are regulated under the GENIUS Act. This means that “decentralized” stablecoins like DAI, USDS, and USDe, which are issued against, and redeemable exclusively for, crypto collateral locked in a Smart Contract, fall outside the Act’s scope. The oldest and largest stablecoin issuer, Tether, is based in El Salvador, and invests its stablecoin reserves in various non-GENIUS Act approved collateral, such as corporate bonds, precious metals, Bitcoin, and equity in other companies, potentially improving its revenue prospects at the cost of increasing redemption risk (

BDO Italia S.p.A, 2025). Rather than bring USDT in compliance with the GENIUS Act, Tether recently announced plans to develop a new stablecoin, USAT, for businesses and institutions operating under the U.S. regulatory framework, but it has not yet launched (

Tether Holdings SA, 2025). In this paper we will mainly focus on stablecoins regulated by the GENIUS Act, like Circle’s USDC. This is partly because, as a publicly traded company, we have special insight into the business practices and financial results of Circle Internet Group Inc., but our analysis can be validly extended to all GENIUS-compliant stablecoins. Although USDT and “decentralized” stablecoins like DAI are legally distinct from GENIUS Act stablecoins, our analytical methodology is sufficiently general to be validly applied to any stablecoin, regulated or unregulated, centralized or decentralized.

To illustrate the revenue prospects for Issuers of GENIUS stablecoins, we first consider Circle’s revenue numbers as they were presented in Circle’s registered offering documents (2025) filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

In

Table 1 we can see that Circle reported revenue of

$1.66 Billion on average reserves of

$33.7 Billion, for an average realized yield on its stablecoin reserves of 4.93% in 2024. Circle also reported “Other Revenue” of

$15.2 Million, totaling to less than 1% of reserve revenue. Circle indicates that “Other Revenue” consisted of revenue from Transaction Services (fees earned from client transactions on Circle’s platform), Integration Services (fees earned from implementing Circle’s tech stack for clients), and Developer Services (fees for specific application solutions for clients). At the time of writing, it costs a little over a dollar’s worth of ETH to send a USDC transaction on Ethereum, and fractions of that to send USDC on one of Ethereum’s second layers, so many are realizing that stablecoins provide an efficient means of payment compared to wire, ACH, and credit card transfers, especially when transacting internationally. However, these transaction fees are not paid to Circle, but to Ethereum validators; Circle only earns fees on the creation and redemption of USDC by users, so its revenue prospects from transaction fees are limited. Although stablecoins do provide Issuers with other sources of revenue, Circle’s revenue is overwhelmingly derived from reserve income.

3. Reserve Yield

Circle’s offering documents state that “We earn reserve income on USDC Reserve assets, at rates at a discount to the prevailing SOFR.” Considering that the average Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) in 2024 was 5.2% (

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2025), Circle’s realized yield of 4.93% represents 95% of the SOFR yield, for a total discount of a mere 25 basis points. From this we can infer that the transaction costs associated with managing its portfolio of assets were very small, and that Circle was generally successful in meeting its target reserve policy.

The total float of Circle’s USDC stablecoin in 2024 started at

$24.5 billion and ended at

$44 billion, and at the time of writing it sits at over

$75 billion (

Coingecko, 2025). If Circle’s growth is indicative of the growth potential of the stablecoin industry as a whole, especially since the passing of the GENIUS Act and the associated regulatory clarity it has brought, many expect Stablecoin Issuers to substantially increase the demand for reserve assets, including short-term U.S. Treasury securities.

U. S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent (

2025) stated that this demand could reach

$2 trillion in just the next few years.

In its April report, the

U.S. Department of the Treasury (

2025) estimated that the total market capitalization of stablecoins could grow from

$234 billion to as much as

$2 trillion by 2028. This represents a staggering 850% increase in a little over three years, and an additional

$1.7 trillion in demand for stablecoin reserve assets. Since bond yields move inversely with prices, as more capital enters the market for stablecoin reserve assets, it is reasonable to expect yields to compress. If yields were to fall substantially, profit margins for all Issuers could shrink.

Ahmed and Aldasoro (

2025) of the Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) recently published a working paper in which they estimate the impact of inflows into stablecoins on the three-month treasury yield. Their analysis suggests that a

$3.5 billion inflow into stablecoins is associated with a 2 to 2.5 basis point drop in T-bill yields, and this effect increased to 3 to 3.5 basis points when controlling for T-bill issuance. With the prevailing T-bill yield of 4.25%, and using a simple linear extrapolation, the BIS’s analysis suggests that it would only take

$500–

$750 billion in additional stablecoin inflows to lower T-bill yields to zero.

1 Of course, because of the difficulty of accurately disentangling the effect of stablecoin inflows on yield, the validity of this simplified extrapolation is dubious, and Ahmed and Aldasoro by no means suggest that this is likely to occur, but their model can nonetheless help us think about how much of an effect the TBAC’s $1.7 trillion projection for stablecoin growth over the next five years is likely to have on T-bill yields. As of July 2025, the face value of U.S. Treasury debt outstanding with a maturity of less than 93 days stood at a mere $2.35 Trillion, and we can assume that many of these securities are already being used as reserves for Money Market Mutual Funds (MMFs) and Repurchase Agreements. If TBAC’s projections come to pass, substantially lower T-bill yields could very well be realized.

Although this would be a welcome change for the U.S. Treasury, there is only so far that yields can drop before they begin to threaten the profit margins of Stablecoin Issuers. If T-bill yields were to fall far enough, Stablecoin Issuers may eschew the securities market, and instead opt to hold their reserves in U.S. bank deposits, and although this would not directly help the U.S. Treasury finance its deficit, it certainly would help to assuage fears that the issuance of stablecoins may cause a run on deposits in the U.S. banking system (

Heeb & Tokar, 2025). Considering that the average yield on three-month certificates of deposit (CDs) is currently 1.4% (

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 2025), no matter how large inflows from stablecoins become, since short term CDs are a close substitute for three-month treasuries, it is reasonable to believe that T-bill yields will not fall below the yield of the three-month CD. Using the same extrapolation from the BIS, we estimate that it would only take

$300–

$500 billion in additional stablecoin inflows to lower three-month T-bill yields to the current level of the three-month CD, so it appears that fears of a run on deposits in the banking system may be overblown.

2However, there are other reasons one might want to switch from bank deposits to payment stablecoins; we have already said that stablecoins offer a fast and efficient means of payment both domestically and internationally. In addition, stablecoins can be transacted 24 h a day, and may also be deposited in various useful Decentralized Financial (DeFi) applications currently unavailable in the traditional banking system. As these use-cases for stablecoins grow in popularity, banks stand to lose financing if they do not improve the value proposition for depositors. Although this is certainly a worry, it is even more reason that banks should investigate issuing their own stablecoins, like Citigroup has recently announced (

Reuters, 2025). As we shall see, stablecoins deployed in DeFi applications generally improve the revenue prospects of Issuers because they cannot be redeemed while locked in Smart Contracts, allowing Issuers to safely earn more revenue from higher-yielding, less-liquid reserve assets. However, if stablecoins become so popular that the yield on reserve assets drops so substantially that Issuance is no longer a profitable business model, then the risk of outflows from the banking system becomes moot. For a clearer idea of the profitability of Stablecoin Issuance, we now turn to the expense side of Circle’s consolidated financials.

4. Expenses

The expense side of a Stablecoin Issuer’s income statement is more diverse, and as detailed data are less available, difficult to estimate. In its offering documents (2025), Circle reported total expenses of just over

$1.5 Billion, which, when subtracted from Circle’s total revenue of

$1.67 Billion, resulted in a total profit margin for the firm of 11%. Circle’s consolidated financial data lists many of the usual operating expenses, including Compensation, G&A, Depreciation and Amortization, IT Infrastructure Costs, Marketing and Mark-to-Market gains totaling

$492 Million. Each of these expenses, along with their size relative to total expenses, total revenue, and net income are reported in

Table 2.

Since the passing of the

GENIUS Act (

2025), the compliance and regulatory costs associated with operating a Stablecoin Issuer have become clearer. Under the Act, Issuers are required to annually prepare audited financial statements. They must also publish monthly information about reserves, including reserve composition, average maturity, and geographic distribution of reserve custodians, and they must have these figures regularly examined by a registered public accounting firm. In addition, Issuers must be ready to furnish the Secretary of the Treasury with a financial condition report upon request, and they must also establish systems for controlling financial and operational risk, as well as compliance with the GENIUS Act, the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), and the Office of Foreign Asset Control’s (OFAC) list of Specially Designated Nationals (SDNs). Since Circle’s offering documents were prepared prior to the passing of the GENIUS Act, it is reasonable to suppose that the Act’s compliance burden will increase Circle’s operational expenses to an extent—however, as a public company, Circle already incurs the compliance costs associated with the 1933 Securities Act, and, as a Money Service Business (MSB), Circle also already complies with the BSA and OFAC requirements, so we do not expect their compliance costs to increase markedly as a result of the GENIUS Act. Nonetheless, the cost of compliance with the GENIUS Act is necessary for all Issuers and can be expected to affect their profitability.

On the other hand, compliance with OFAC sanctions can also create revenue opportunities for Issuers because they can expect to receive reserve income associated with frozen deposits in perpetuity. At the time of writing, Circle enjoys the reserve income from over

$100 Million frozen USDC with little possibility of redemption (

Dune, 2025). Issuers cannot help themselves to the reserves underlying frozen USDC since there is always a chance that an Externally Owned Account (EOA) is removed from the SDN list, yet nonetheless, it is important to note that there is a silver lining for Issuers who comply with OFAC’s sanctions regime.

5. Distribution Costs

In its consolidated financials (2025), Circle’s largest expense by far did not come from operations, but from “Distribution, Transaction, and Other Costs”, totaling over

$1 Billion, and accounting for over 60% of its total revenue. The next largest expense was Compensation, coming in at 15.7% of revenue, and then General and Administrative Expenses of 8.2% of revenue, but these operating costs were dwarfed by Circle’s distribution costs, as can be seen in

Table 3.

Circle incurs distribution costs as a result of its “Collaboration Agreement,” “under which we [Circle] make payments to Coinbase for its role in the distribution of USDC and growth in the USDC ecosystem”. Although the GENIUS Act prohibits Issuers from paying yield directly to stablecoin holders, they may nonetheless make payments to third parties to incentivize adoption of an Issuer’s stablecoin by digital asset intermediaries like Coinbase (

BPI Staff, 2025).

Circle Internet Group, Inc. (

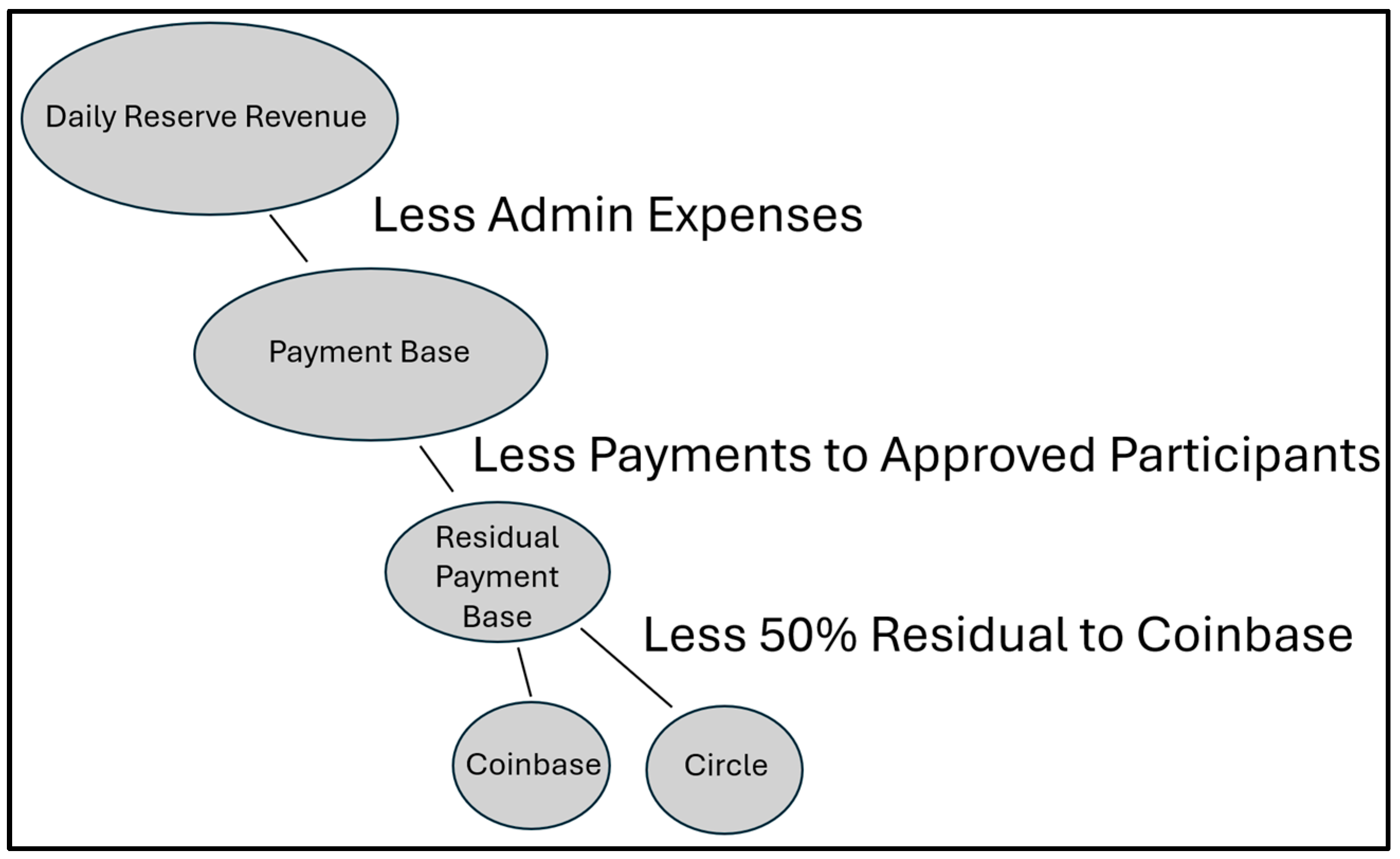

2025) notes that “These payments are determined based on the daily income generated from the reserve backing USDC, less the management fees charged by non-affiliated third parties for managing such reserves (such as asset management and custody fees) and certain other expenses, which is referred to as the ‘payment base.’” Circle retains for itself “a portion ranging from an annualized low-double-digit basis point to high tenth of a basis point based on the amount of USDC in circulation on such day.” This is structured to compensate Circle for their role as a Stablecoin Issuer and to reimburse them for the indirect costs of issuing stablecoins and the management of the associated reserves, including accounting, treasury, and regulatory compliance costs. After these costs are deducted from the payment base, Circle, Coinbase and other “approved participants” in the USDC ecosystem “receive an amount equal to the remaining payment base multiplied by the percentage of such stablecoin that is held in the applicable party’s custodial products or managed wallet services at the end of such day.” Since a large proportion of circulating USDC exists as balances held by EOAs, collateral locked in Smart Contracts, or custodied by Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs) not approved under the Collaboration Agreement, not all USDC outstanding is eligible for these pro-rata payments. After all payments to approved participants (including Circle itself, as it operates its own USDC platform) are deducted from the payment base, Coinbase receives 50% of the residual payment base, as can be seen in

Figure 1.

As a result of its 50% residual payment under the Collaboration Agreement, Coinbase currently earns a proportion of the payout base greater than its pro-rata contribution to the USDC ecosystem. In theory, this allows Coinbase to pay out higher rewards to USDC holders than any other distributor in the USDC ecosystem. Its “Most-Favored Distributor” status likely arises from Coinbase’s leading position as a US-based Virtual Currency Exchange (VCE), as well as from its minority investment in Circle (

Coinbase Global, Inc., 2025b). At the time of writing, Coinbase offers its users 4.1% annual yield on USDC held on Coinbase Exchange (

Coinbase, 2025), just below the prevailing T-bill yield of 4.25%.

In addition to its Collaboration Agreement with Coinbase, in 2024 Circle entered into a two-year distribution agreement with Binance (

Circle Internet Group, Inc., 2025). Under this agreement, Binance agreed to maintain a portion of its treasury in USDC, and in return, Circle made a one-time payment to Binance of

$60.25 million. Circle also onboarded Binance as the second approved participant under its Collaboration Agreement and therefore agreed to compensate Binance alongside Coinbase for its pro-rata contribution to liquidity in the USDC ecosystem. Like Coinbase, Binance also offers a 4.2% yield on USDC held on its exchange, likely financed from proceeds received from Circle (

Binance, 2025).

Other, smaller Stablecoin Issuers have similar reserve revenue sharing agreements with distributors, such as Paxos, whose website (

Global Dollar Network, 2025) advertises to potential distribution partners that they can, “Receive up to 100% of the returns generated by assets backing USDG held on your platform,” and on top of that they can also, “Earn additional revenue for minting, acceptance, and more.” So, in addition to sharing reserve revenue with distribution partners like Circle does, Paxos is also willing to share other revenue generated by stablecoin users.

Although the authors could find no publicly available revenue sharing policy for Tether, USDT users have reported (

McClellan, 2025) receiving payments from VCEs for holding USDT on-exchange in the past. Though the authors could not corroborate these claims, it appears that at some point, Tether may have pioneered the practice of making payments to exchanges according to their pro-rata contribution to USDT liquidity. We theorize that Tether likely began compensating distribution partners when it first encountered competition from decentralized stablecoins, like DAI. As the first Stablecoin, USDT used to be the only option for VCEs who wanted to offer an alternative Dollar-denominated unit of account to their clients, but when MakerDAO’s DAI Stablecoin launched on Ethereum in 2017, it became possible for VCEs to offer their clients a decentralized alternative. The DAI stablecoin could initially only be created by encumbering Ether tokens in a Smart Contract and borrowing DAI into existence. These Smart Contracts, known as “Collateralized Debt Positions” (CDPs), accrued interest according to a built-in “Stability Fee” rate, which would be added, every block, to a CDP’s outstanding debt (

MakerDAO, 2017). Third parties who held DAI could deposit it into a different Smart Contract, called the “DAI Savings Rate” (DSR), and earn interest paid in DAI that was theoretically financed by the stability fees paid by CDPs. After the launch of DAI and the DSR, VCEs could deposit client DAI into the DSR to earn yield while a user’s DAI was in their custody and withdraw it on-demand when a client requested a withdrawal. It stands to reason that Tether was first compelled to directly compensate VCE’s according to the amount of USDT held in their custody to compete with yield-bearing alternatives like DAI.

No matter the practice’s origins, it is clear that some form of reserve revenue sharing with stablecoin intermediaries has already become, and likely will continue to be, an industry-wide standard of practice for both centralized and decentralized stablecoins alike. It follows that, contrary to what many people assume, the profitability of Stablecoin Issuance is unrelated to the yield on reserve assets, whether they be US Treasuries or CDPs. Regardless of how high or low the yield is on reserve assets, competitive dynamics compel Stablecoin Issuers to forfeit a large portion of their reserve income to distribution partners

In prohibiting Issuers from directly compensating users to hold their stablecoin, the GENIUS Act essentially forces them to interpolate distribution partners to incentivize the use of their stablecoin. Issuers have no choice but to pay a large proportion of their reserve revenue directly to VCEs, VASPs and other intermediaries as a cost of doing business. Although Issuers like Circle retain all the reserve income associated with USDC held on its own platform and half of the reserve income associated with USDC held in non-approved intermediaries, EOAs, and Smart Contracts, the GENIUS Act’s prohibition on direct payments to holders gives stablecoin distributors an advantage in competing with Issuers for stablecoin users. Issuers can only attract users to their platforms with lower transaction costs or useful application features, while distributors can do these things as well as incentivize holders directly. This strongly suggests that distribution, not issuance, will be the key to a successful stablecoin as the industry matures.

6. Distribution Dynamics

This fact is also evident when one views the stablecoin industry through Microeconomic analysis. Under the GENIUS Act, all stablecoins must be backed by high quality assets that trade in a liquid market with similar yields. Although some Issuers may attempt to distinguish their stablecoins from others by limiting risk, for example through overcollateralization or via a higher proportion of cash reserves, these efforts would decrease both reserve income and capital efficiency, putting these Issuers at a disadvantage when competing for preferred distribution and capital investment. Some users may prefer a stablecoin with minimized market risk, but from a distribution perspective, all GENIUS Act compliant stablecoins are essentially substitutes, and so economic theory suggests that the only way Issuers will be able to distinguish themselves to distributors will be through competitive reserve income sharing arrangements. It follows that Issuers will be forced to make larger payments to distributors in their efforts to grow market share and economies of scale until economic profits from Issuance have been competed away. Considering Circle’s one-time payment to Binance and its sweetheart deal with Coinbase, it appears that these economic forces are already in motion, and that it is only a matter of time before GENIUS Act-compliant Stablecoin Issuance devolves into a commodity business. Not only will regulated Issuers have to compete for distribution with one another, but they will also have to compete with yield-bearing unregulated stablecoins as well.

As we have seen with Coinbase and Binance, distributors themselves face competitive pressure to pay out to their users a large portion of the pro-rata reserve income flowing from Issuers, and so the operational efficiency and market-power of distributors will likely be the key to success in the stablecoin industry. Distributors may earn more yield by hosting decentralized stablecoins, but this comes with added risk. In a way, the GENIUS Act defines the “risk free rate” in the context of stablecoin distribution; distributors may host non-GENIUS Act stablecoins on their platforms, but to induce risk-averse users to hold alternative stablecoins in their custody, they will be compelled to pay higher rewards to users. Whichever distributor offers the best risk-adjusted stablecoin yields for a variety of user risk-tolerances will attract the most user deposits to their platform and consequently, enjoy the most opportunities to earn profits by cross-selling related products and services to users. These profits can be, in turn, redistributed to stablecoin users, further improving the distributor’s competitive position. It follows that distributors who can synergistically earn profits from complementary product and service offerings will be able to offer the highest risk-adjusted yields and the most attractive platforms for users of stablecoins, whether they are centralized or decentralized.

7. Bank Distributors

Section five of the

GENIUS Act (

2025) explicitly allows banks to operate Stablecoin Issuer subsidiaries. Bank holding companies, who already possess established distribution networks in their bank and brokerage subsidiaries, are competitively positioned to capture synergies from cross-selling financial products and absorb stablecoin distribution and compliance costs as well as administrative expenses associated with the management and custody of stablecoin reserves. Pure play issuers like Circle must necessarily rely on banks and brokerage firms for the management and custody of stablecoin reserves, and they have no choice but to share reserve revenue with distributors in exchange for “Most-Favored Stablecoin” status on their platforms. Banks, with their existing distribution networks and brokerage subsidiaries, are uniquely positioned to outcompete both Issuers like Circle, as well as incumbent distributors like Coinbase and Binance. Faced with the economies of scale and product cross-selling opportunities enjoyed by banks, distributors like Coinbase and Binance will be hard-pressed to compete with them for stablecoin deposits. Indeed, we are already beginning to see distributors collaborate with U.S. banks rather than compete with them, as evidenced by Coinbase’s recent partnership with JP Morgan Chase (

Coinbase Global, Inc., 2025a).

8. Conclusions

As illustrated, the top-line revenue of a Stablecoin Issuer is limited by the yield on short-term US treasury securities. As more firms issue stablecoins and purchase reserve assets, yields on these assets can be expected to fall, straining the unit economics of issuance. This tendency, coupled with the reality of fixed GENIUS Act compliance costs, tends to favor large firms whose size allows them to achieve economies of scale and firms that already incur the costs of compliance in the course of their existing business. Both these effects favor large banks with brokerage subsidiaries; banks already comply with the 1933 and 1934 Securities and Exchange Acts, the BSA, and OFAC requirements, and their brokerage subsidiaries stand ready to help them trade and custody stablecoin reserve assets efficiently.

We have also shown that a large proportion of Issuer reserve revenue can be expected to be paid out to distributors who service the end-users of stablecoins. Since regulated stablecoins are almost perfect substitutes, the best way for distributors to distinguish themselves from one another is through higher risk-adjusted payments to users, or through exclusive products and/or complementary services. Since banks already have large client bases in many different lines of business and can earn synergistic revenues from cross-selling, the profits from which can be used to finance higher payments to stablecoin holders, banks have a substantial advantage in this arena. Banks with brokerage subsidiaries are well positioned to offer a multitude of products and services to stablecoin clients, whether they be exclusive financial products, easy transfer of payment stablecoins between bank, mortgage and brokerage accounts, or preferred pricing on bank and brokerage products (credit card rewards, discounted wealth management fees, etc.). We therefore conclude that large banks with brokerage subsidiaries, who already possess established distribution networks of customers, will likely become the dominant Stablecoin Issuers.

The industry dynamics we have identified indicate that the issuance and distribution of stablecoins are fundamentally linked. We have shown that banks will have an advantage offering both services, and so there is a strong possibility that the stablecoin industry eventually consolidates around a few bank issuers and distributors. If this were to occur, and bank-associated stablecoin distributors become sufficiently entrenched, there is a chance they cease being subject to market discipline and begin keeping a larger portion of stablecoin reserve income for themselves. Entrenched bank stablecoin issuers may, instead of investing in risk-free T-bills, choose to invest stablecoin reserves in uninsured deposits in their own banks, providing for themselves a cheap source of liquidity with which to finance investments in higher-yielding assets, increasing systemic risk. Luckily, under the GENIUS Act, the primary Federal stablecoin regulator may force Stablecoin Issuers to diversify their reserve assets across U.S. banks, so it is likely that no Stablecoin Issuer will be allowed to exclusively deposit stablecoin reserves into their own bank. Rather, any bank-issued stablecoin reserves will likely be required to be distributed across U.S. brokerage firms and bank deposits, helping to ensure that stablecoin reserve deposits remain FDIC-insured to the greatest possible extent. Obviously, banks would prefer not to give their competitors liquidity, so they will opt to invest reserves in their own banks, brokerage firms, and money market funds before they fund their competitors with stablecoin reserves. However, if yields on T-bills and SOFR fall far enough such that deposits in other banks offer the best risk-adjusted yield for stablecoin reserves, then the GENIUS Act essentially compels banks to work together in issuing and distributing stablecoins to customers.

The GENIUS Act, therefore, does not exclusively benefit large banks, but it also tends to promote the soundness and integrity of the entire US financial system. If we are correct, and banks do prove to be the most efficient stablecoin issuers, and most GENIUS Act stablecoins come to be backed by bank deposits, then payment stablecoins will effectively become tokenized bank deposits, and we will wind up right where we started.