Explaining the Determinants of International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) Disclosure: Evidence from Latin American Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Context of IFRS in Latin America

3. Literature Review and Study Hypothesis

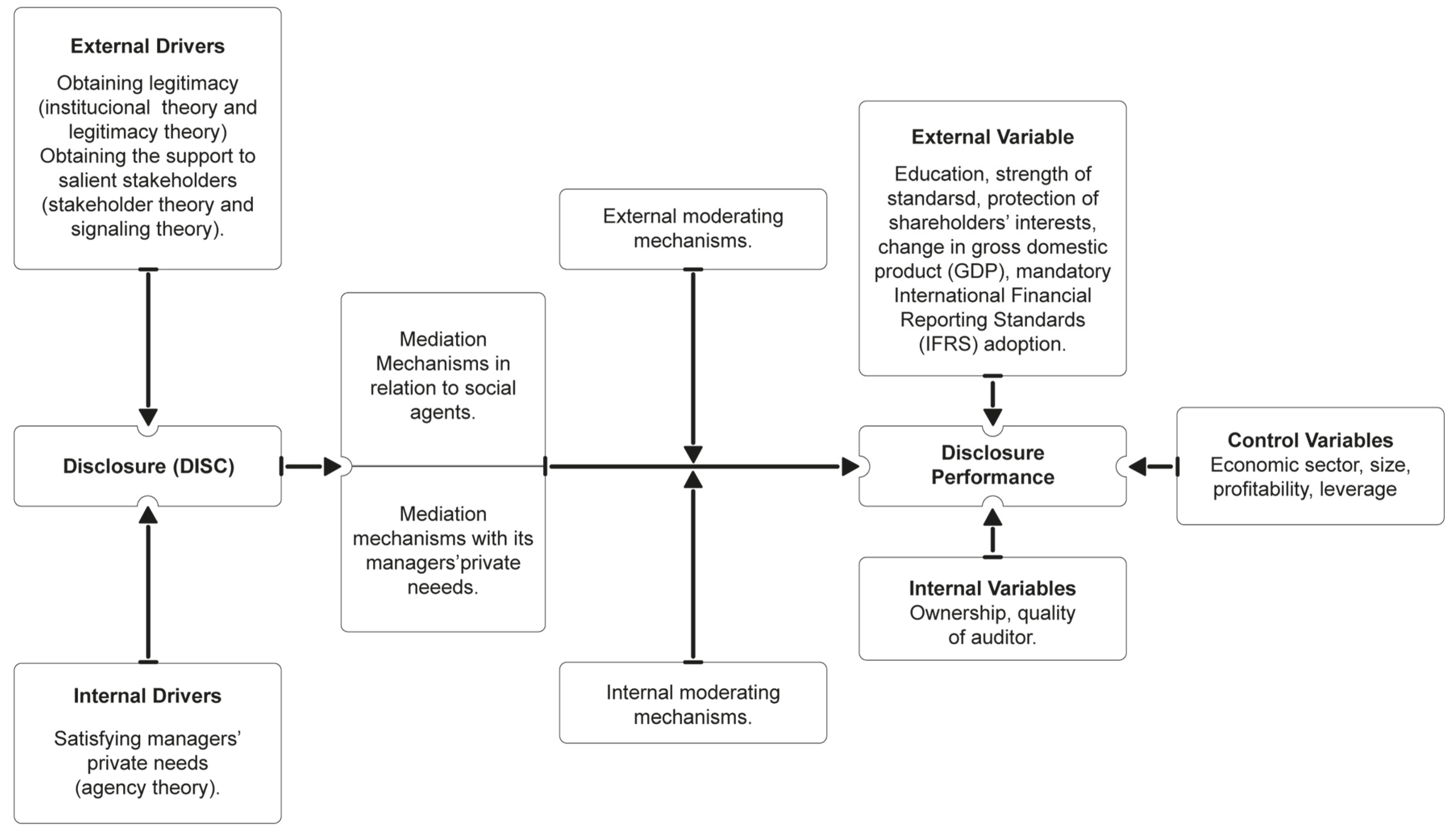

3.1. Theoretical Framework

3.2. Measurement of Disclosure Indices

3.3. Determinants of Mandatory Information Disclosure

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample

4.2. Measurements

4.2.1. Dependent Variables

Disclosure Level Indices

Disclosure Change Indices

4.2.2. Independent Variables

4.2.3. Control Variables

4.3. Estimation Model

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Regression Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

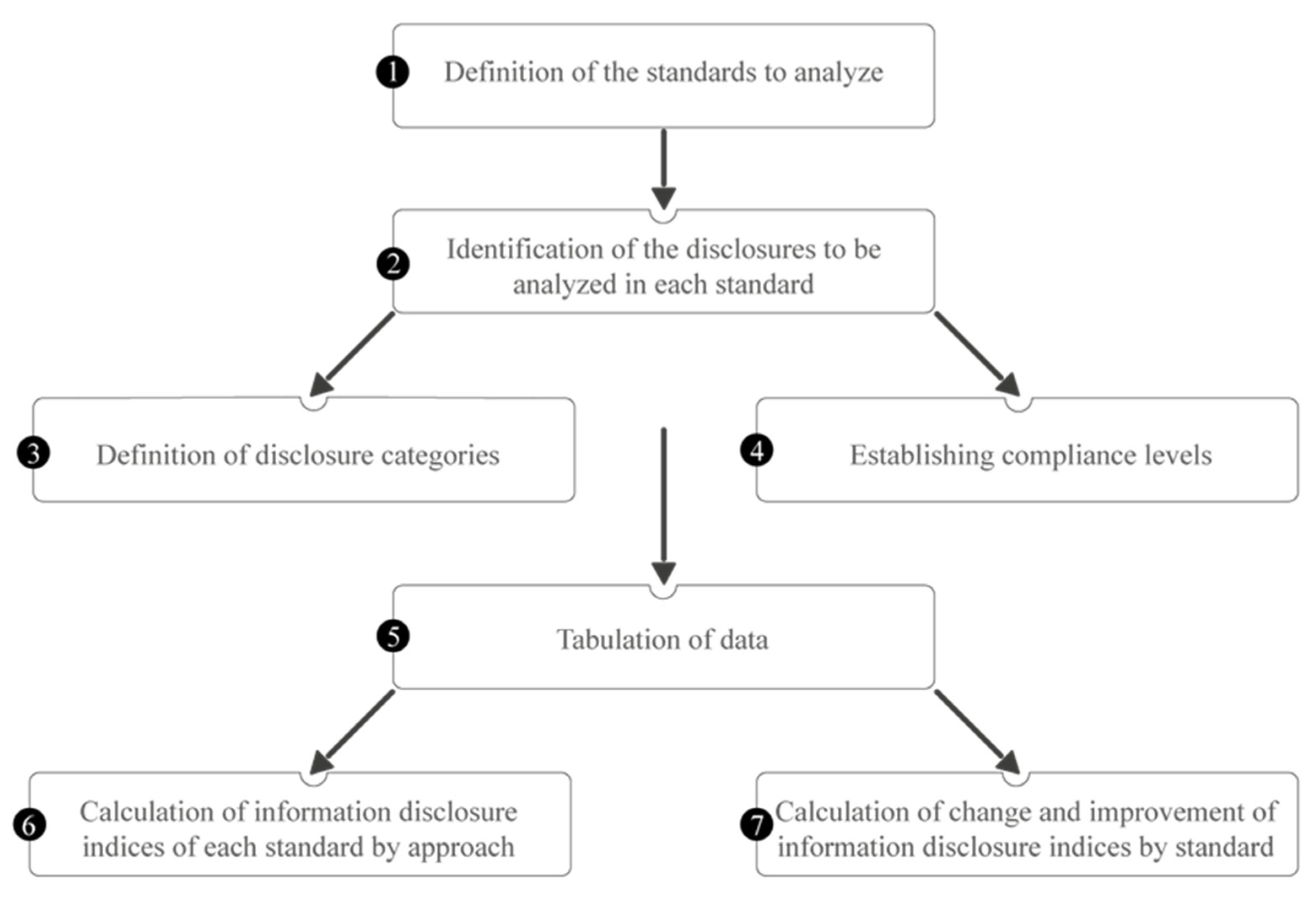

Appendix A. Procedure to Estimate Self-Constructed Indices

- 1.

- Definition of the standards to analyze

- 2.

- Identification of the disclosure items to be analyzed in each standard

| Code | Disclosure Description |

|---|---|

| PPE_D1 | Gross book value |

| PPE_D2 | Accumulated depreciation value |

| PPE_D3 | Lifespan or depreciation rates |

| PPE_D4 | Reconciliation between book values at the beginning and end of the period |

| PPE_D5 | Depreciation for the period, whether recognized as an expense in the period results or included in the cost of other assets (such as inventories) |

| PPE_D6 | Accumulated depreciation at the end of the period |

| PPE_D7 | Valuation (revalued model): revaluation date, use of an independent appraiser, revalued value versus cost model value, revaluation surplus |

| PPE_D8 | PPE information in guarantee in compliance with obligations |

| PPE_D9 | PPE information in construction process |

| PPE_D10 | PPE information in procurement commitment |

| PPE_D11 | PPE Valuation—Significant Changes: residual values, decommissioning costs, useful life, and depreciation method |

| PPE_D12 | Book value of PPE temporarily out of service |

| PPE_D13 | Book value of fully depreciated PPE still in operation |

| PPE_D14 | Book value of PPE retired and not classified as available-for-sale assets |

| PPE_D15 | For PPE measured using the cost model, the fair value is reported if there is a significant change |

| PPE_D16 | Deterioration value |

| PPE_D17 | Deterioration value: if it has not been disclosed in ORI third party compensation for PPE whose value has been deteriorated, lost or surrendered |

| PPE_D18 | Impairment losses |

| Code | Disclosure Description |

|---|---|

| INV_D1 | Inventory valuation including measurement policies, formulas or methods |

| INV_D2 | Inventory valuation—Recognized value: global and by categories |

| INV_D3 | Inventory destination: sale (cost of sales), consumption (inventory cost), use (expense), and recognition amounts |

| INV_D4 | Valuation—net realizable value (VNR): inventory amount valued at VNR; discount value recognized as period expense |

| INV_D5 | Amount of inventory recognized as an expense in the period |

| INV_D6 | Amount of inventory discounts recognized as an expense in the period |

| INV_D7 | Valuation—VNR: discounts, amount |

| INV_D8 | Inventory delivered as collateral for debt compliance |

- 3.

- Definition of disclosure categories

- 4.

- Establishing compliance levels

- 5.

- Tabulation of data

- 6.

- Calculation of disclosure level indices of each standard by approach

- 7.

- Calculation of changes disclosure indices by standard

| Prior to year of adoption | |||

| 1 | 0 | ||

| After year of adoption | 1 | a | b |

| 0 | c | d | |

- Maintenance indices

- Improvement index

References

- Ab Abonwara, K. M., Ahmad, N. L. B., & Halim, H. B. A. (2021). Determinants and consequence of adopting International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS): A systematic literature review. International Journal of Contemporary Management and Information Technology, 1(3), 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Abasi, A. K., Oseifuah, E. K., & Munzhelele, F. N. (2022). Formulation of weighted disclosure index for evaluating accounting disclosure and its application to JSE listed firms. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 27, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Agana, J. A., Zamore, S., & Domeher, D. (2025). IFRS adoption: A systematic review of the underlying theories. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 23(4), 1677–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. S., Neel, M., & Wang, D. (2013). Does mandatory adoption of IFRS improve accounting quality? Preliminary evidence. Contemporary Accounting Research, 30(4), 1344–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbaba, C., İbiş, C., Yanık, S., & Aytürk, Y. (2023). Disclosure quality of goodwill impairment testing: Evidence from Turkey. International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting, 15(1), 88–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akisik, O., Wanderley, C., & Frezatti, F. (2014). Financial reporting and foreign direct investments in Latin America. In Accounting in Latin America (Vol. 14, pp. 41–74). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akra, M., Eddie, I. A., & Ali, M. J. (2010). The influence of the introduction of accounting disclosure regulation on mandatory disclosure compliance: Evidence from Jordan. The British Accounting Review, 42(3), 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaqtari, F. A., Hashed, A. A., & Shamim, M. (2021). Impact of corporate governance mechanism on IFRS adoption: A comparative study of Saudi Arabia, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates. Heliyon, 7(1), e05848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, B., Brown, P., & Tarca, A. (2008). An investigation of compliance with international accounting standards by listed companies in the Gulf Co-Operation Council member states. The International Journal of Accounting, 43(4), 425–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, P., Dionysiou, D., & Tsalavoutas, I. (2018). Mandated disclosures under IAS 36 Impairment of Assets and IAS 38 Intangible Assets: Value relevance and impact on analysts’ forecasts. Applied Economics, 50(7), 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, K. O., Awunyo-Vitor, D., Mireku, K., & Ahiagbah, C. (2016). Compliance with international financial reporting standards: The case of listed firms in Ghana. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 14(1), 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, J. J., & Archambault, M. E. (2003). A multinational test of determinants of corporate disclosure. The International Journal of Accounting, 38(2), 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R. (2006). International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS): Pros and cons for investors. Accounting and Business Research, 36(Suppl. 1), 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R. (2016). Why we do international accounting research. Journal of International Accounting Research, 15(2), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessler, W., Gonenc, H., & Tinoco, M. H. (2023). Information asymmetry, agency costs, and payout policies: An international analysis of IFRS adoption and the global financial crisis. Economic Systems, 47(4), 101129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek-Jaworska, A., & Matusiewicz, A. (2015). Determinants of the level of information disclosure in financial statements prepared in accordance with IFRS. Journal of Accounting and Management Information Systems (JAMIS), 14(3), 453–482. [Google Scholar]

- Boujelben, S., & Kobbi-Fakhfakh, S. (2020). Compliance with IFRS 15 mandatory disclosures: An exploratory study in telecom and construction sectors. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 18(4), 707–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, S., & Trombetta, M. (2008). On the global acceptance of IAS/IFRS accounting standards: The logic and implications of the principles-based system. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 27(6), 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, J., Rodrigues, L. L., & Craig, R. (2017). Assessing international accounting harmonization in Latin America. Accounting Forum, 41(3), 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christanto, I. W., & Fuad, F. (2023). The impact of IFRS on value relevance of accounting information: Evidence from the Indonesian stock exchange. Jurnal Akuntansi dan Perpajakan, 9(1), 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damak-Ayadi, S., Sassi, N., & Bahri, M. (2020). Cross-country determinants of IFRS for SMEs adoption. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 18(1), 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De George, E. T., Li, X., & Shivakumar, L. (2016). A review of the IFRS adoption literature. Review of Accounting Studies, 21(3), 898–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Morais, C. R. F., Amorim, K. V. N. M., Junior, D. B. C. V., Domingos, S. R. M., & Ponte, V. M. R. (2019). Accounting information quality of Latin American firms: The influence of the regulatory environment. Revista Evidenciação Contábil & Finanças, 7(2), 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moura, A. A. F., Altuwaijri, A., & Gupta, J. (2020). Did mandatory IFRS adoption affect the cost of capital in Latin American countries? Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 38, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moura, A. A. F., & Gupta, J. (2019). Mandatory adoption of IFRS in Latin America: A boon or a bias. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 60, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebaid, I. E. S. (2022). IFRS adoption and accounting-based performance measures: Evidence from an emerging capital market. Journal of Money and Business, 2(1), 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeigba, J., & Amenkhienan, F. (2017). The influence of IFRS adoption on corporate transparency and accountability: Evidence from New Zealand. Australasian Accounting, Business & Finance Journal, 11(3), 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhamma, A. (2024). Determinants of national IFRS adoption: Evidence from the Middle East and North Africa region. International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation, 20(1–2), 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eluyela, F. D., Adetula, D. T., Oladipo, O. A., Nwanji, T. I., Adegbola, O., Ajayi, A., & Faleye, A. (2019). Pre and post adoption of IFRS based financial statement of listed small medium scale enterprises in Nigeria. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET), 10(1), 1097–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Elzahar, H., Hussainey, K., Mazzi, F., & Tsalavoutas, I. (2015). Economic consequences of key performance indicators’ disclosure quality. International Review of Financial Analysis, 39, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z. (2021). The impact of institutional factors and IFRS on the value relevance of accounting information: Evidence from Ah Shares [Master’s thesis, University of Malaya (Malaysia)]. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, S., & Lourenço, I. (2018). Determinants of complicance with mandatory disclosure: Research evidence. Determinants of Complicance with Mandatory Disclosure: Research Evidence, 15(2), 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Frynas, J. G., & Yamahaki, C. (2016). Corporate social responsibility: Review and roadmap of theoretical perspectives. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25(3), 258–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaum, M., Schmidt, P., Street, D. L., & Vogel, S. (2013). Compliance with IFRS 3-and IAS 36-required disclosures across 17 European countries: Company and country-level determinants. Accounting and Business Research, 43(3), 163–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C., & Annisette, M. (2012). The role of transnational institutions in framing accounting in the global south. In Handbook of accounting and development. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2009). Basic econometrics (5th ed.). McGraw Hill Inc. [Google Scholar]

- International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation. (2025, March 1). Analysis of the IFRS accounting jurisdiction profiles. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/use-around-the-world/use-of-ifrs-standards-by-jurisdiction/#analysis-of-the-169-profiles (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Irvine, H. (2008,The global institutionalization of financial reporting: The case of the United Arab Emirates. Accounting Forum, 32(2), 125–142. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0155998207000737 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Istiningrum, A. A. (2020). Corporate governance, IFRS disclosure, and stock liquidity in Indonesian Mining Companies. In 4th International Conference on Management, Economics and Business (ICMEB 2019) (pp. 271–278). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, M., Yapa, P. W. S., & Kraal, D. (2016). IFRS adoption in ASEAN countries: Perceptions of professional accountants from Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 12(2), 211–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhmani, O. (2017). Corporate governance and the level of Bahraini corporate compliance with IFRS disclosure. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 18(1), 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M. R., & Riya, A. I. (2022). Compliance of disclosure requirements of IFRS 15: Empirical evidence from developing economy. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 19(3), 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenessey, Z. (1987). The primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary sectors of the economy. Review of Income and Wealth, 33(4), 359–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaghaany, M., & Jaber, A. I. (2023). The impact of mandatory adoption of international accounting standards (IAS/IFRS) on the relationship between accounting estimates and cash flows: An empirical study. Russian Law Journal, 11(9S), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlifi, F. (2022). Re-examination of the internet financial reporting determinants. EuroMed Journal of Business, 17(4), 519–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawalata, J., Salle, I. Z., & Yuliana, L. (2024). The impact of international financial reporting standards on global accounting practices. Advances in Applied Accounting Research, 2(2), 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuz, C., & Wysocki, P. D. (2016). The economics of disclosure and financial reporting regulation: Evidence and suggestions for future research. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(2), 525–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B., Siciliano, G., Venkatachalam, M., Naranjo, P., & Verdi, R. S. (2021). Economic consequences of IFRS adoption: The role of changes in disclosure quality. Contemporary Accounting Research, 38(1), 129–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, H., Jara, M., & Cabello, A. (2020). IFRS adoption and accounting conservatism in Latin America. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 33(3/4), 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaquias, R. F., & Zambra, P. (2018). Disclosure of financial instruments: Practices and challenges of Latin American firms from the mining industry. Research in International Business and Finance, 45, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzi, F., André, P., Dionysiou, D., & Tsalavoutas, I. (2017). Compliance with goodwill-related mandatory disclosure requirements and the cost of equity capital. Accounting and Business Research, 47(3), 268–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzi, F., Slack, R., & Tsalavoutas, I. (2018). The effect of corruption and culture on mandatory disclosure compliance levels: Goodwill reporting in Europe. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 31, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgarejo, M. (2024). Earnings quality of multinational corporations: Evidence from Latin America before and after IFRS implementation. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 35(4), 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M. Z., & Rahaman, A. S. (2005). The adoption of international accounting standards in Bangladesh: An exploration of rationale and process. Accounting, Auditing, & Accountability, 18(6), 816–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misirlioglu, I. U., Tucker, J., & Boshnak, H. A. (2022). Drivers of mandatory disclosure in GCC region firms. Accounting Research Journal, 35(3), 382–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mısırlıoğlu, İ. U., Tucker, J., & Yükseltürk, O. (2013). Does mandatory adoption of IFRS guarantee compliance? The International Journal of Accounting, 48(3), 327–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnif, Y., & Borgi, H. (2020). The association between corporate governance mechanisms and compliance with IFRS mandatory disclosure requirements: Evidence from 12 African countries. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 20(7), 1371–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnif Sellami, Y., & Borgi Fendri, H. (2017). The effect of audit committee characteristics on compliance with IFRS for related party disclosures: Evidence from South Africa. Managerial Auditing Journal, 32(6), 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongrut, S., Tello Marín, M., Torres Postigo, M. del C., & Fuenzalida O’Shee, D. (2021). IFRS adoption and firms’ opacity around the world: What factors affect this relationship? Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, 26(51), 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongrut, S., & Winkelried, D. (2019). Unintended effects of IFRS adoption on earnings management: The case of Latin America. Emerging Markets Review, 38, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Mendoza, J. A., Sepulveda Yelpo, S. M., Veloso Ramos, C. L., Delgado Fuentealba, C. L., & Fuentes Solis, R. A. (2022). Earnings management and country-level characteristics as determinants of stock liquidity in Latin America. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting/Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, 51(1), 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. T. T., Nguyen, H. T. T., & Van Nguyen, C. (2023). Analysis of factors affecting the adoption of IFRS in an emerging economy. Heliyon, 9(6), e17331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N. G., & Nguyen, N. T. (2023). Determinants of voluntary international financial reporting standards application: Review from theory to empirical research. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(11), 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobes, C. (2006). The survival of international differences under IFRS: Towards a research agenda. Accounting and Business Research, 36(3), 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobes, C. (2011). IFRS practices and the persistence of accounting system classification. Abacus, 47(3), 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2017). Report of the chair of the working group on the future size and membership of the organisation to council framework for the consideration of prospective members. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Osinubi, I. S. (2020). The three pillars of institutional theory and IFRS implementation in Nigeria. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 10(4), 575–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. (2021). Financial reporting under economic policy uncertainty. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 19(2), 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papke, L. E., & Wooldridge, J. M. (1996). Econometric methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401 (k) plan participation rates. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11(6), 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo, E., Martins, E., & Pontes Girão, L. F. D. A. (2014). Accounting information quality in Latin-and North-American public firms. In Accounting in Latin America (pp. 1–39). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Pricope, C. F. (2016). The role of institutional pressures in developing countries: Implications for IFRS. Theoretical and Applied Economics, 23(2), 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez García, M. D. P., Cortez Alejandro, K. A., Méndez Sáenz, A. B., & Garza Sánchez, H. H. (2017). Does an IFRS adoption increase value relevance and earnings timeliness in Latin America? Emerging Markets Review, 30(C), 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhou, N. C., Douagi, W. B. M., Hussainey, K., & Alqatan, A. (2021). The impact of IFRS mandatory adoption on KPIs disclosure quality. Risk Governance and Control: Financial Markets & Institutions, 11(3), 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, K., & Khlif, H. (2016). Adoption of and compliance with IFRS in developing countries: A synthesis of theories and directions for future research. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 6(1), 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana Santos, E., Rodrigues Ponte, V. M., & Rocha Mapurunga, P. V. (2014). Mandatory IFRS adoption in Brazil (2010): Index of compliance with disclosure requirements and some explanatory factors of firms reporting. Revista Contabilidade & Finanças-USP, 25(65), 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, K. (2005). The introduction of international accounting standards in Europe: Implications for international convergence. European Accounting Review, 14(1), 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, D. L., & Bryant, S. M. (2000). Disclosure level and compliance with IASs: A comparison of companies with and without US listings and filings. The International Journal of Accounting, 35(3), 305–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, D. L., & Gray, S. J. (2002). Factors influencing the extent of corporate compliance with international accounting standards: Summary of a research monograph. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation, 11(1), 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, D. L., Gray, S. J., & Bryant, S. M. (1999). Acceptance and observance of international accounting standards: An empirical study of companies claiming to comply with IASs. The International Journal of Accounting, 34(1), 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalavoutas, I. (2011). Transition to IFRS and compliance with mandatory disclosure requirements: What is the signal? Advances in Accounting, 27(2), 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalavoutas, I., & Dionysiou, D. (2014). Value relevance of IFRS mandatory disclosure requirements. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 15(1), 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalavoutas, I., Evans, L., & Smith, M. (2010). Comparison of two methods for measuring compliance with IFRS mandatory disclosure requirements. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 11(3), 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalavoutas, I., Tsoligkas, F., & Evans, L. (2020). Compliance with IFRS mandatory disclosure requirements: A structured literature review. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 40, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weetman, P. (2006). Discovering the ‘international’ in accounting and finance. The British Accounting Review, 38(4), 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehri, F., & Chouaibi, J. (2013). Determinants of the adoption of international accounting standards (IAS/IFRS) by developing countries. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences, 18(35), 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Adoption Year | Status in OECD |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 2012 | Invitation to become a member in 2024 |

| Chile | 2009 | Member since 2010 |

| Colombia | 2015 | Member since 2020 |

| Mexico | 2012 | Member since 1994 |

| Peru | 2011 | Invitation to become a member in 2022 |

| Country | Firms | Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 44 | 220 |

| Chile | 61 | 305 |

| Colombia | 18 | 90 |

| Mexico | 28 | 140 |

| Peru | 17 | 85 |

| Total | 168 | 840 |

| Level | Variable | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Mandatory IFRS adoption (Years before Adoption = 1) | A dummy variable that took the value of 1 for the years preceding IFRS adoption. It was constructed individually for each country. | Own database |

| Mandatory IFRS adoption (Years after Adoption = 1) | A dummy variable that took the value of 1 for the years following IFRS adoption. It was constructed individually for each country. | Own database | |

| Education | Measurement of the quality of a country’s education system as the extent to which it met the needs of a competitive economy. A 7-point scale was used, where 1 indicated “not well at all” and 7 indicated “very well.” | World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index | |

| Strength of Standard | Measurement of the robustness and transparency of financial reporting and auditing practices within a country in each year. It was measured on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 represented weak standards and practices, and 7 represented strong standards and practices. | World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index | |

| Protection of Minority Shareholders | Measurement of the strength of a country’s legal framework and regulatory environment in safeguarding the rights of minority shareholders, using a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 represented extremely weak protection and 10 meant strong protections. | World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index | |

| Change in GDP | Annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate, measured in %. | World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index | |

| Firm | Ownership | Sum of the ownership percentages of the first three shareholders with the highest ownership stakes. | Own database |

| BIG4 | Dummy variable coded as 1 if the firm was audited by EY, Deloitte, PwC, or KPMG, and 0 otherwise. | Own database |

| Argentina (2010–2014) | Chile (2007–2011) | Colombia (2013–2017) | Mexico (2010–2014) | Peru (2009–2013) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | |

| Dependent Variables | ||||||||||

| General IAS 16 | 30.8% | 7.1% | 26.0% | 13.0% | 37.0% | 14.1% | 32.5% | 10.4% | 41.8% | 5.0% |

| Required IAS 16 | 81.0% | 16.7% | 64.4% | 26.4% | 79.8% | 25.8% | 75.7% | 16.2% | 94.1% | 8.0% |

| General IAS 2 | 23.1% | 11.0% | 17.5% | 16.6% | 22.4% | 17.4% | 29.0% | 15.9% | 27.4% | 6.5% |

| Required IAS 2 | 59.8% | 27.6% | 42.1% | 37.6% | 52.6% | 37.7% | 60.0% | 27.2% | 66.3% | 8.1% |

| Variables at country level | ||||||||||

| Education | 3.24 | 0.14 | 3.22 | 0.14 | 3.35 | 0.13 | 3.00 | 0.15 | 2.54 | 0.15 |

| Strength of Standards | 3.84 | 0.05 | 5.57 | 0.02 | 4.64 | 0.13 | 4.86 | 0.12 | 4.90 | 0.10 |

| Protection Minority Shareholders | 3.43 | 0.06 | 5.13 | 0.18 | 4.08 | 0.06 | 4.23 | 0.11 | 4.34 | 0.16 |

| Change in GDP | 6.4% | 3.7% | 0.1% | 10.2% | 8.1% | 6.8% | 3.6% | 4.6% | 8.4% | 3.4% |

| Variables at sector level | ||||||||||

| Primary | 36.4% | 48.2% | 9.8% | 29.8% | 22.2% | 41.8% | 14.3% | 35.1% | 64.7% | 48.1% |

| Secondary | 47.7% | 50.1% | 24.9% | 43.3% | 27.8% | 45.0% | 42.9% | 49.7% | 35.3% | 48.1% |

| Tertiary | 11.4% | 31.8% | 46.2% | 49.9% | 22.2% | 41.8% | 28.6% | 45.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Quaternary | 4.5% | 20.9% | 19.0% | 39.3% | 27.8% | 45.0% | 14.3% | 35.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Variables at firm level | ||||||||||

| Size | 11.01 | 1.86 | 11.82 | 2.78 | 14.13 | 2.15 | 14.05 | 1.33 | 12.54 | 1.58 |

| Return on Equity | 11.6% | 16.8% | 6.4% | 16.0% | 5.8% | 13.1% | 9.2% | 12.7% | 11.6% | 15.1% |

| Leverage | 45.9% | 22.2% | 37.1% | 24.7% | 38.4% | 19.0% | 47.1% | 18.9% | 34.4% | 11.8% |

| Ownership | 46.3% | 37.3% | 54.1% | 35.1% | 32.9% | 36.2% | 36.1% | 35.8% | 61.2% | 28.9% |

| BIG4 | 52.3% | 50.1% | 59.0% | 49.3% | 92.2% | 26.9% | 89.3% | 31.0% | 77.6% | 41.9% |

| Number of firms per year (N) | 44 | 61 | 18 | 28 | 17 | |||||

| Argentina (IFRS Adoption Year = 2012) | Chile (IFRS Adoption Year = 2009) | Colombia (IFRS Adoption Year = 2015) | Mexico (IFRS Adoption Year = 2012) | Peru (IFRS Adoption Year = 2011) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | |

| Dependent Variables | ||||||||||

| Maintain Disclosure IAS 16 | 91.7% | 15.5% | 62.3% | 26.1% | 70.7% | 29.6% | 84.2% | 18.1% | 93.1% | 8.5% |

| Maintain Non-Disclosure IAS 16 | 61.4% | 46.5% | 29.5% | 39.8% | 19.4% | 33.5% | 61.0% | 37.7% | 17.6% | 39.3% |

| Improve Disclosure IAS 16 | 3.0% | 7.4% | 29.5% | 21.6% | 16.7% | 16.2% | 13.1% | 15.9% | 6.9% | 8.5% |

| Maintain Disclosure IAS 2 | 89.8% | 20.1% | 77.3% | 29.5% | 74.1% | 37.1% | 85.7% | 25.9% | 100.0% | 0.0% |

| Maintain Non-Disclosure IAS 2 | 62.5% | 47.2% | 22.1% | 37.8% | 33.3% | 45.7% | 63.1% | 46.3% | 100.0% | 0.0% |

| Improve Disclosure IAS 2 | 5.3% | 14.3% | 18.0% | 24.0% | 16.7% | 26.2% | 10.7% | 18.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Independent Variables at country level | ||||||||||

| Change in GDP | 3.7% | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 4.3% | 0.0% | 5.9% | 0.0% | 9.5% | 0.0% |

| Independent Variables at sector level | ||||||||||

| Primary | 36.4% | 48.7% | 9.8% | 30.0% | 22.2% | 42.8% | 14.3% | 35.6% | 64.7% | 49.3% |

| Secondary | 47.7% | 50.5% | 24.6% | 43.4% | 27.8% | 46.1% | 42.9% | 50.4% | 35.3% | 49.3% |

| Tertiary | 11.4% | 32.1% | 45.9% | 50.2% | 22.2% | 42.8% | 28.6% | 46.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Quaternary | 4.5% | 21.1% | 19.7% | 40.1% | 27.8% | 46.1% | 14.3% | 35.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Independent Variables at corporate level | ||||||||||

| Size | 10.96 | 1.86 | 12.08 | 2.81 | 14.11 | 2.25 | 14.19 | 1.32 | 12.73 | 1.62 |

| Profitability | 8.8% | 15.2% | 9.4% | 13.8% | 6.5% | 14.7% | 8.9% | 12.5% | 11.8% | 12.6% |

| Leverage | 47.6% | 21.0% | 36.7% | 24.5% | 41.3% | 18.6% | 47.6% | 18.2% | 33.5% | 12.2% |

| Ownership | 46.0% | 37.8% | 53.9% | 35.4% | 34.3% | 37.1% | 33.9% | 35.8% | 61.2% | 29.7% |

| BIG4 | 52.3% | 50.5% | 60.7% | 49.3% | 94.4% | 23.6% | 92.9% | 26.2% | 76.5% | 43.7% |

| Number of firms per year (N) | 44 | 61 | 18 | 28 | 17 | |||||

| Dependent Variable | Model 1 General Disclosure (IAS 16) | Model 2 Required Disclosure (IAS 16) | Model 3 General Disclosure (IAS 2) | Model 4 Required Disclosure (IAS 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation Method | 2SLS | OLS | OLS | OLS |

| Constant | 0.134529 * | 0.766840 *** | −0.136836 * | −0.162873 |

| (0.062763) | (0.126953) | (0.076391) | (0.162331) | |

| Size | 0.010764 *** | 0.013987 *** | 0.016779 *** | 0.035815 *** |

| (0.001736) | (0.003491) | (0.002101) | (0.004464) | |

| Profitability | −0.006866 | 0.006345 | 0.019549 | −0.007535 |

| (0.022155) | (0.044880) | (0.027006) | (0.057387) | |

| Leverage | 0.093178 *** | 0.109190 *** | 0.113690 *** | 0.295726 *** |

| (0.019191) | (0.033198) | (0.019976) | (0.042450) | |

| Primary | 0.054940 *** | 0.081449 *** | 0.137464 *** | 0.333179 *** |

| (0.012106) | (0.024547) | (0.014770) | (0.031387) | |

| Secondary | 0.049412 *** | 0.097807 *** | 0.165765 *** | 0.359074 *** |

| (0.011054) | (0.022417) | (0.013489) | (0.028663) | |

| Tertiary | 0.016229 | 0.023993 | 0.031783 ** | 0.082631 *** |

| (0.011336) | (0.022959) | (0.013815) | (0.029358) | |

| Mandatory IFRS adoption (Years before Adoption = 1) | −0.018110 * (0.010076) | −0.040658 ** (0.020452) | −0.010793 (0.012306) | −0.016651 (0.026151) |

| Mandatory IFRS adoption (Years after Adoption = 1) | 0.044973 *** (0.009385) | 0.086220 *** (0.019029) | 0.024081 ** (0.011450) | 0.044582 * (0.024332) |

| Education | −0.026765 * | −0.045843 | −0.008696 | −0.005696 |

| (0.013769) | (0.027918) | (0.016799) | (0.035698) | |

| Strength of standards | −0.030255 *** | −0.079876 *** | 0.009213 | −0.007734 |

| (0.006633) | (0.013464) | (0.008102) | (0.017216) | |

| Protection of Minority shareholders | 0.027172 *** | 0.025916 *** | −0.006608 | −0.016124 |

| (0.004681) | (0.009433) | (0.005676) | (0.012061) | |

| Change in GDP | 0.208357 *** | 0.441688 *** | 0.074469 | 0.139966 |

| (0.050375) | (0.102148) | (0.061465) | (0.130613) | |

| Ownership | 0.033326 *** | 0.065647 *** | 0.015573 | 0.052347 ** |

| (0.009411) | (0.019062) | (0.011470) | (0.024373) | |

| Audited by BIG4 | 0.005914 | 0.022088 | 0.017883 * | 0.021883 |

| (0.008784) | (0.017776) | (0.010697) | (0.022730) | |

| R-squared | 36.1% | 29.8% | 40.4% | 42.6% |

| N | 840 | 840 | 840 | 840 |

| Dependent Variable | Maintain Disclosure | Maintain Non-Disclosure | Improve Disclosure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 IAS 16 | Model 2 IAS 2 | Model 3 IAS 16 | Model 4 IAS 2 | Model 5 IAS 16 | Model 6 IAS 2 | |

| Constant | 0.801499 *** | 1.182804 *** | 0.54301 *** | −0.06403 | 0.156676 ** | −0.145565 |

| (0.100474) | (0.115529) | (0.19616) | (0.18485) | (0.078516) | (0.088003) | |

| Size | −0.023219 *** | −0.028193 *** | −0.01137 | 0.01376 | 0.010653 | 0.018577 ** |

| (0.008476) | (0.009746) | (0.01655) | (0.01559) | (0.006623) | (0.007424) | |

| Profitability | −0.063029 | −0.147374 | −0.13425 | −0.22511 | 0.117107 | 0.126747 |

| (0.125336) | (0.144117) | (0.24470) | (0.23059) | (0.097944) | (0.109779) | |

| Leverage | 0.121681 | −0.158625 | 0.03110 | 0.45133 *** | −0.031227 | 0.058880 |

| (0.085081) | (0.097830) | (0.16611) | (0.15653) | (0.066487) | (0.074521) | |

| Primary | 0.072412 | 0.006524 | 0.14516 | 0.18282 | −0.075323 | 0.016672 |

| (0.060585) | (0.069663) | (0.11828) | (0.11146) | (0.047344) | (0.053065) | |

| Secondary | 0.128643 ** | 0.017723 | 0.16768 | 0.19040 * | −0.081369 * | 0.039900 |

| (0.055338) | (0.063630) | (0.10804) | (0.10181) | (0.043244) | (0.048470) | |

| Tertiary | 0.150838 *** | −0.023246 | 0.23987 ** | 0.03060 | −0.109195 ** | 0.051831 |

| (0.056985) | (0.065523) | (0.11125) | (0.10484) | (0.044531) | (0.049912) | |

| Change in GDP | 4.092845 *** | 2.565335 *** | 146,415 | 7.06960 *** | −2.977099 *** | −2.166158 *** |

| (0.646012) | (0.742812) | (126123) | (118852) | (0.504829) | (0.565828) | |

| Ownership | −0.008632 | 0.040504 | −0.19064 ** | −0.03778 | 0.065667 * | −0.007788 |

| (0.047528) | (0.054650) | (0.09279) | (0.08744) | (0.037141) | (0.041629) | |

| Audited by BIG4 | −0.030867 | −0.033559 | −0.16402 * | −0.19347 ** | 0.033274 | 0.058394 |

| (0.046285) | (0.053220) | (0.09036) | (0.08515) | (0.036170) | (0.040540) | |

| R-squared | 24.7% | 13.9% | 7.2% | 29.7% | 27.4% | 14.5% |

| N | 168 | 168 | 168 | 168 | 168 | 168 |

| Hypotheses | Explanatory Variable | Predicted Sign | Standard | Compliance (Yes/No) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1. Mandatory IFRS adoption results in increased financial information disclosure | Mandatory IFRS adoption (Year after Adoption = 1) | (+) | IAS 16 | Yes | Supported |

| IAS 2 | Yes | ||||

| H2. The institutional characteristics of a country influence the implementation of IFRS | Education | (+) | IAS 16 | No | Partially Supported |

| IAS 2 | No | ||||

| Strength of standards | (+) | IAS 16 | No | ||

| IAS 2 | No | ||||

| Protection of minority shareholders | (+) | IAS 16 | Yes | ||

| IAS 2 | No | ||||

| Change in GDP | (+) | IAS 16 | Yes | ||

| IAS 2 | No | ||||

| H3. Corporate governance exerts a positive effect on the extent of financial disclosure under IFRS | Ownership | (+) | IAS 16 | Yes | Partially Supported |

| IAS 2 | Yes (Only Required Disclosure) | ||||

| H4. Audit quality exerts a positive effect on the extent of financial disclosure under IFRS | Audited by BIG4 | (+) | IAS 16 | No | Partially Supported |

| IAS 2 | Yes (Only General Disclosure) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González Muñoz, R.I.; Rodríguez, Y.E.; Maldonado, S. Explaining the Determinants of International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) Disclosure: Evidence from Latin American Countries. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100567

González Muñoz RI, Rodríguez YE, Maldonado S. Explaining the Determinants of International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) Disclosure: Evidence from Latin American Countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(10):567. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100567

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález Muñoz, Rosa Isabel, Yeny Esperanza Rodríguez, and Stella Maldonado. 2025. "Explaining the Determinants of International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) Disclosure: Evidence from Latin American Countries" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 10: 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100567

APA StyleGonzález Muñoz, R. I., Rodríguez, Y. E., & Maldonado, S. (2025). Explaining the Determinants of International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) Disclosure: Evidence from Latin American Countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(10), 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100567