South Africa’s Vice Chancellors’ Historical and Future Salary Predictors from 2016 to 2026

Abstract

1. Introduction

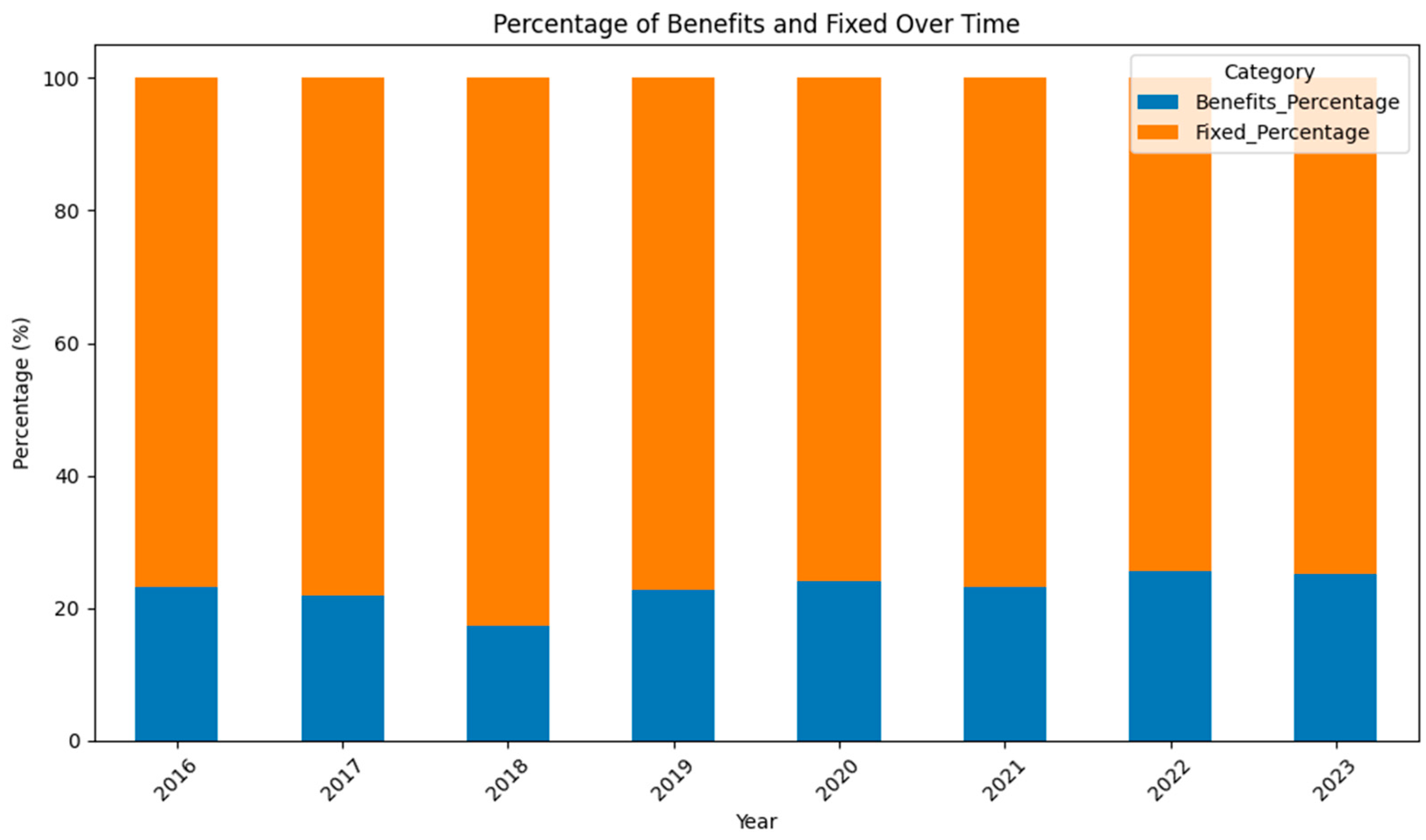

- To determine the benefits as a percentage of the fixed salary;

- To identify the relationship between the predictors and VCs’ salaries;

- To forecast and analyse the history of VC’s fixed and benefits costs from 2016 to 2026.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Agency Theory

2.1.2. Institutional Theory

2.1.3. Predictors of Executive Remuneration

2.2. Research Methodology

2.2.1. Research Design

2.2.2. Sample and Sampling Method

2.2.3. Source of Data

- The annual reports must be available on Google;

- They must list the student enrolment, revenue, and VC salaries;

- They must include the Statement of Financial Position and Statement of Comprehensive Income.

2.2.4. Data Collection Procedure

2.2.5. Conceptual and Operational Definitions of Variables

2.2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Benefits as a Percentage of Fixed Salary

3.3. Relationship Between Target and Predictor Variables

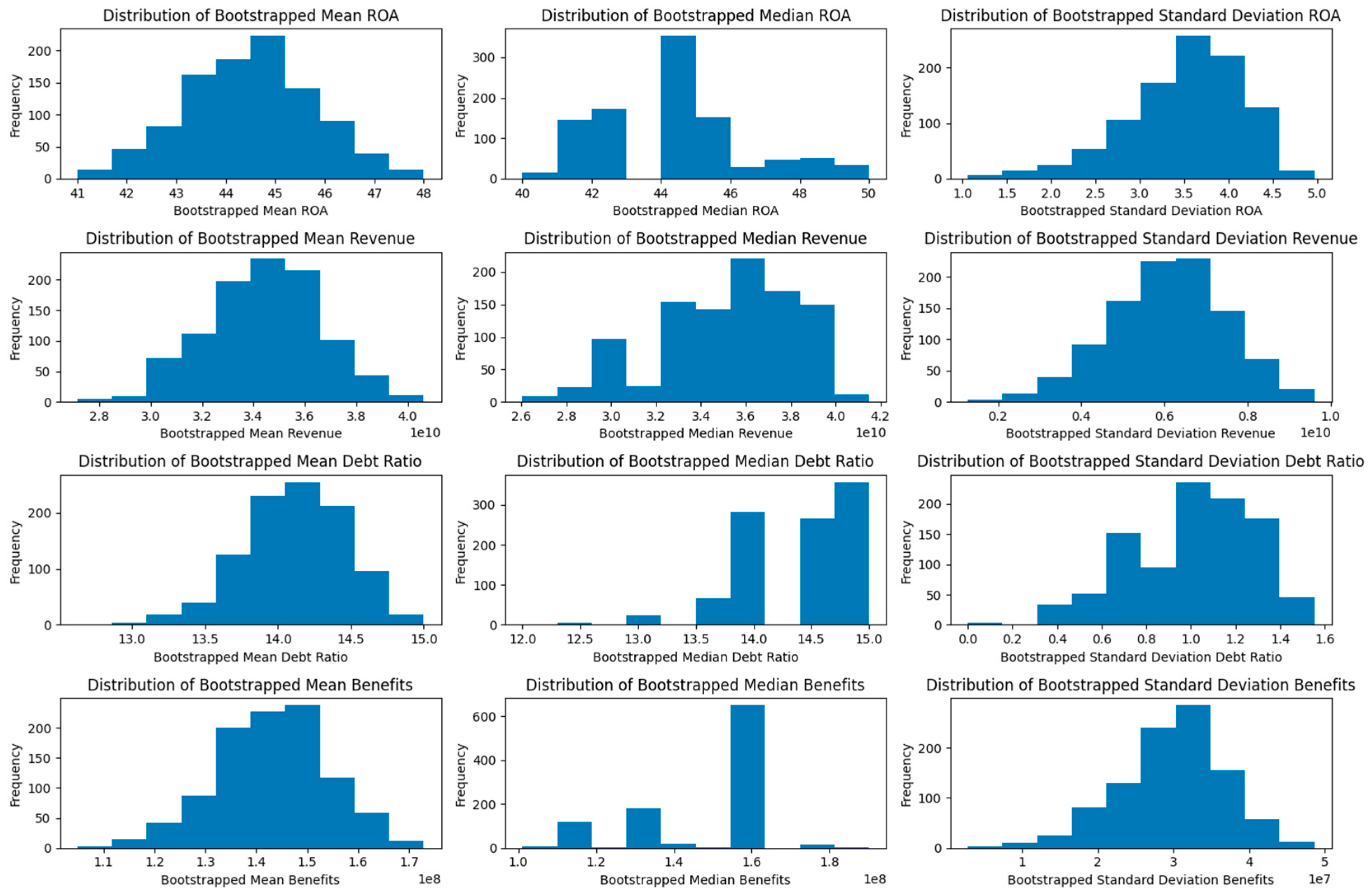

- Revenue: The 95% confidence interval does not include zero, indicating the correlation is statistically significant at the 5% level. The mean bootstrapped correlation coefficient was 0.7718. On average, there was a positive linear relationship between Revenue and Fixed.

- Debt ratio: The 95% confidence interval does not include zero, indicating the correlation is statistically significant at the 5% level. The mean bootstrapped correlation coefficient was 0.8427. On average, this suggests a positive linear relationship between the Debt ratio and Fixed Assets.

- Benefits: The 95% confidence interval does not include zero, indicating the correlation is statistically significant at the 5% level. The mean bootstrapped correlation coefficient was 0.8876. On average, there is a positive linear relationship between Benefits and Fixed.

- Total students: The 95% confidence interval does not include zero, indicating the correlation is statistically significant at the 5% level. The mean bootstrapped correlation coefficient was 0.7876. On average, there is a positive linear relationship between the Total Number of students and the Fixed Amount.

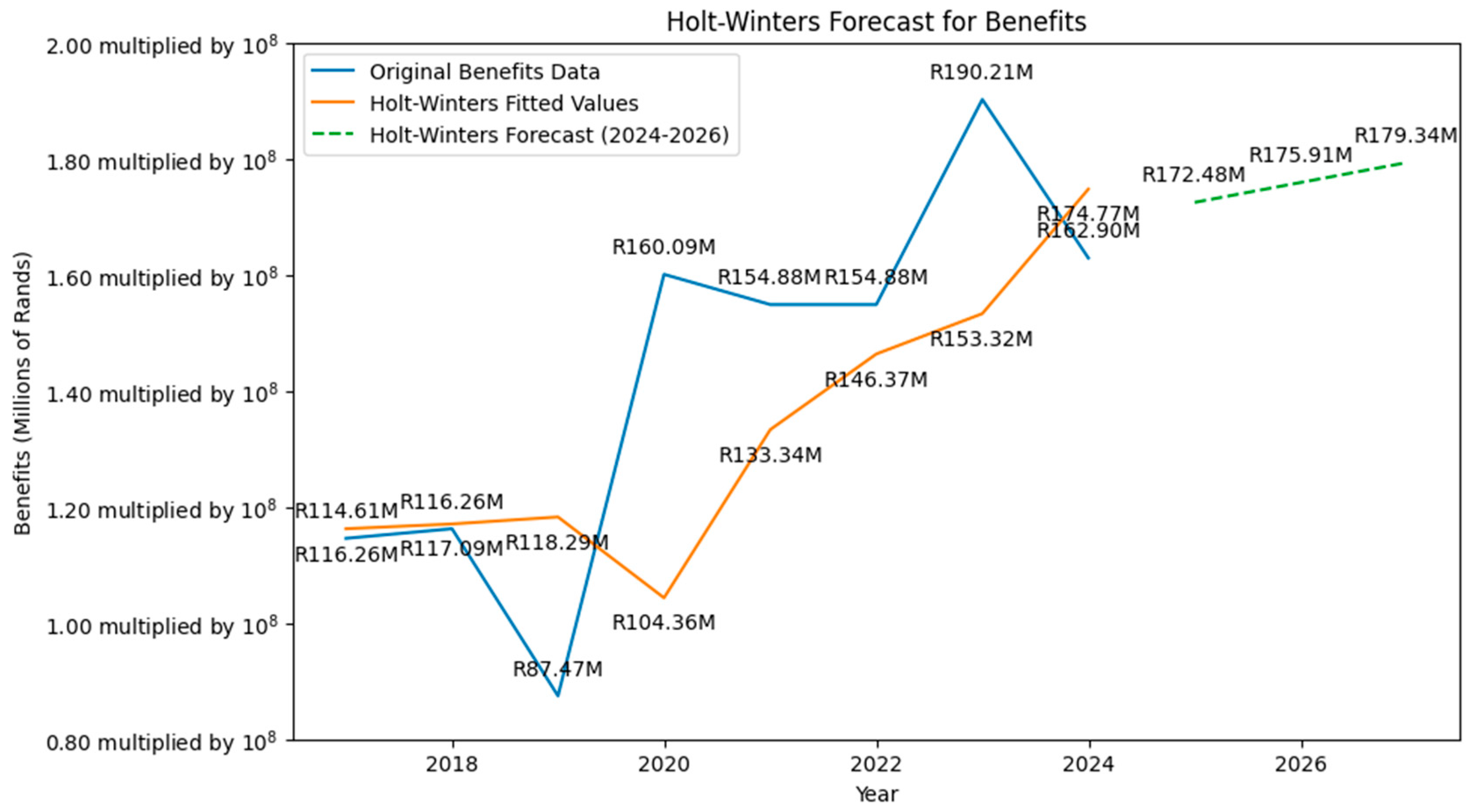

3.4. Historical and Forecast of VCs’ Benefits and Fixed Costs from 2024 to 2026

3.4.1. Benefits of Historical Salary Benefits and Forecasting

- Historical Data (Blue Line): This line reflects the actual ‘Benefits’ values from 2016 to 2023. You can see the specific amounts for each year (e.g., R114.61M in 2016, R160.09M in 2019, peaking at R190.21M in 2022, and then R162.90M in 2023). This line shows the past trend and any fluctuations in Benefits.

- Holt–Winters Fitted Values (Orange Line): This line represents the values that the Holt–Winters model calculated for the historical period (2016–2023) based on the identified trend (additive trend in this case). These fitted values try to capture the underlying pattern in the historical data, smoothing out some of the year-to-year variations. It is observable that how closely the orange line follows the blue line; the differences between them indicate the model’s error in capturing the exact historical values. For example, the fitted value for 2022 is R174.77M, which is lower than the actual R190.21M.

- Holt–Winters Forecast (Green Dashed Line): This line extends from the end of the historical data (2023) and shows the model’s predictions for the next three years (2024, 2025, and 2026). The forecast is based on the trend extrapolated from historical data. The forecast values are approximately R172.48M for 2024, R175.91M for 2025, and R179.34M for 2026. The upward slope of the dashed line indicates that the model forecasts a continued increasing trend in Benefits over the next three years (2024 to 2026).

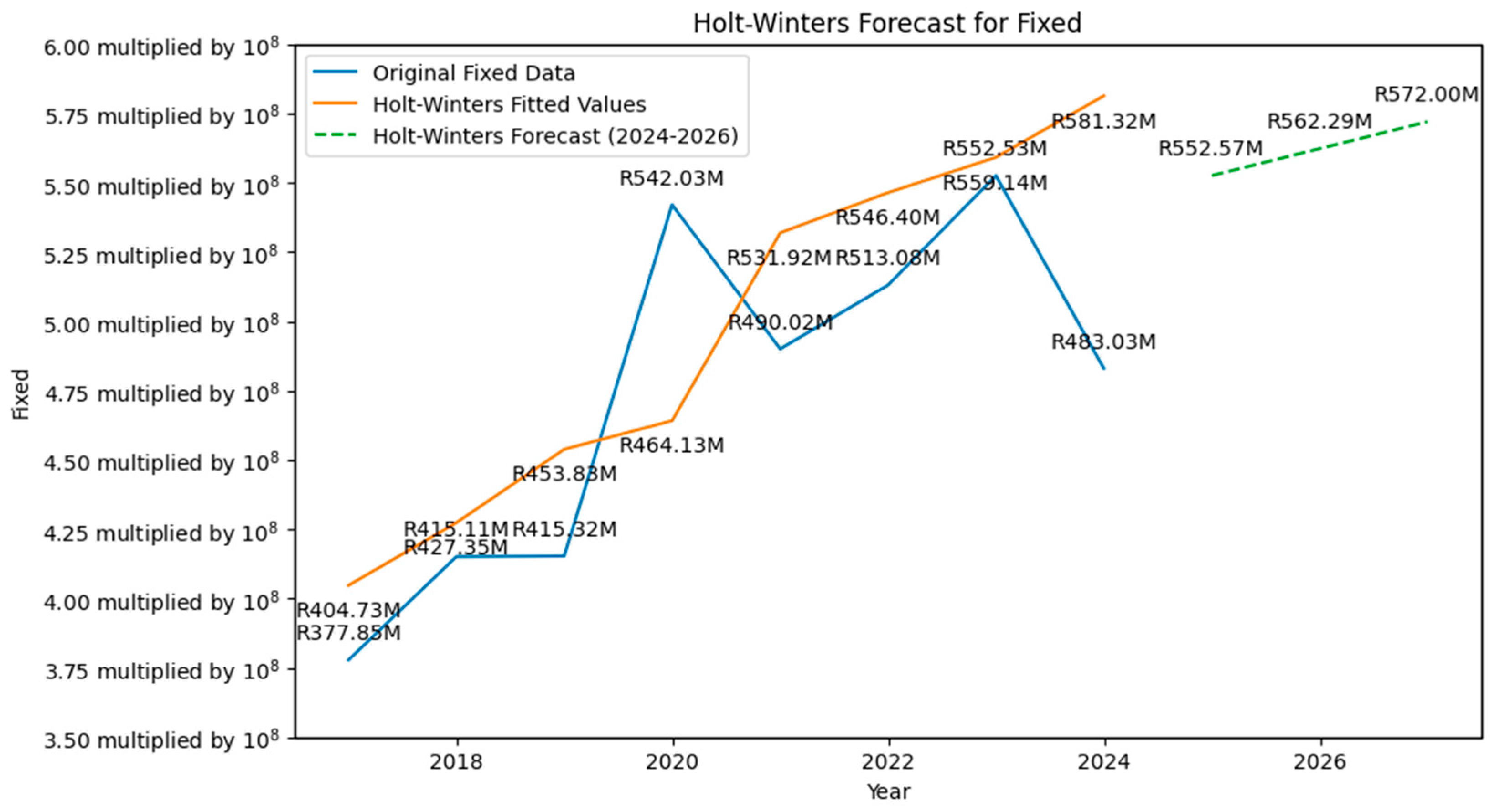

3.4.2. Fixed Historical Salary and Forecasting

- Historical Data (Blue Line): This line shows the actual Fixed values from 2016 to 2023. You can see the specific amounts (e.g., R377.85M in 2016, R542.03M in 2019, R552.53M in 2022, and then R483.03M in 2023). This line shows the past trend and fluctuations in Fixed expenses.

- Holt–Winters Fitted Values (Orange Line): This line represents the Holt–Winters model’s calculated values for the historical period (2016–2023) based on its identified additive trend. Similar to Benefits, this line smooths the historical data. One can observe where the orange line deviates from the blue line, indicating where the model’s trend does not perfectly match the historical fluctuations. For instance, the fitted value for 2023 is R581.32M, while the actual value was R483.03M, reflecting a significant difference.

- Holt–Winters Forecast (Green Dashed Line): This line shows the model’s predictions for Fixed from 2024 to 2026. The forecast values were approximately R552.57M for 2024, R562.29M for 2025, and R572.00M for 2026. The upward slope of the dashed line suggests that the model forecasts a continued increasing trend in fixed expenses over the next three years, similar to Benefits.

4. Discussion

5. Managerial Implication(s)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Manaseer, S. R. (2024). The impact of debt ratio on financial stability through the mediating role of capital adequacy: Evidence from the regulatory framework of the banking industry. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 13(4), 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, A. (2023). Investigating the relationship between pay disparity and organisational performance [Master’s thesis, University of Cape Town]. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11427/37962 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Bartlett, J. (2012). A compensation comparison: Determinants of compensation for chief executive officers and university presidents [Claremont McKenna College]. Available online: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1508&context=cmc_theses (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Basson, A., & Charles, M. (2023). Embattled vice-chancellor Phakeng leaves UCT with R12m golden handshake. News24. Available online: https://www.news24.com/southafrica/news/exclusive-embattled-vice-chancellor-phakeng-leaves-uct-with-r12m-golden-handshake-20230222 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Blagg, K., & Blom, E. (2018). Evaluating the return on investment in higher education: An assessment of individual and State level returns (pp. 1–20). Urban Institute. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99078/evaluating_the_return_on_investment_in_higher_education.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Brealey, R. A., Myers, S. C., & Allen, F. (2011). Principles of corporate finance: S&P market insight (10th ed). McGraw-Hill Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, D. J., Eide, E. R., & Ehrenberg, R. G. (1999). Does it pay to attend an elite private college? Cross-cohort evidence on the effects of college type on earnings. The Journal of Human Resources, 34(1), 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussin, M., & Modau, M. F. (2015). The relationship between chief executive officer remuneration and financial performance in South Africa between 2006 and 2012. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussin, M., & Ncube, M. (2017). Chief executive officer and chief financial officer compensation relationship to company performance in state-owned entities. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 20(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D., & Vermeulen, F. (2016). Stop paying executives for performance. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/02/stop-paying-executives-for-performance (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Caruana, E. J., Hernandez-Sanchez, R. M. J., & Solli, P. (2015). Longitudinal studies. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 7(11), E537–E540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloete, M., & Marimuthu, F. (2019). Basic accounting for non-accountants. Van Schaik. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Higher Education. (2024). Annual report 23/24 (pp. 1–318). DHET. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, P., Viviers, S., & Thomas, K. (2020). Corporate finance: A South African perspective (G. Els, Ed.; 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, A. L., & Afitska, N. (2023). Professional bodies. Journal of Professions and Organization, 10(1), 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- James, A., & Tripathi, V. (2021). Time series data analysis and ARIMA modelling to forecast the short-term trajectory of the acceleration of fatalities in Brazil caused by the corona virus (COVID-19). PeerJ Life and Environment, 9, E11748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karton, J. (2020). International arbitration as comparative law in action. Journal of Dispute Resolution, 2020, 1–37. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3654734 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Khuluvhe, M., Netshifhefhe, E., & Negogogo, V. (2022). Post-school education and training monitor: Macro-indicator trends (pp. 1–133). Department of Education and Training. Available online: https://www.dhet.gov.za/Planning%20Monitoring%20and%20Evaluation%20Coordination/Post-School%20Education%20and%20Training%20Monitor%20-%20Macro-Indicator%20Trends%20-%20March%202021.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Kučera, J., Vochozka, M., & Rowland, Z. (2021). The ideal debt ratio of an agricultural enterprise. Sustainability, 13(9), 4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. (2024). Board gender diversity and nonprofit CEO compensation: Implications for gender pay gap. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 53(1), 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedy, P. D., & Ormrod, J. E. (2015). Practical research: Planning and design. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Lucey, B., Urquhart, A., & Zhang, H. (2022). UK vice chancellor compensation: Do they get what they deserve? The British Accounting Review, 54(4), 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madingwane, R., Mazenda, A., Nhede, N., & Munyeka, W. (2023). Employee performance and remuneration in public service of South Africa. Journal of Public Administration, Finance and Law, 27, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, J. F., & Mitnick, B. M. (2010). Reputation shifting. Journal of Public Affairs, 10(4), 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleka, M. J. (2023). Using ensemble method to predict employee atrrition at the multinational consulting corporation. IBC, Swakopmund Hotel and Entertainment Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Maleka, M. J., & Schultz, C. M. (2021). The relationship between performance indicators and executives’ remuneration in the South African higher education sector. Academia Letters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleka, M. J., Sifolo, P., & Henama, U. (2024). Executive gender pay trends in the South African public tourism sector. Journal of Global Business and Technology, 20(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Maree, K. (Ed.). (2016). First steps in research (2nd ed.). Van Schaik. [Google Scholar]

- Martocchio, J. J. (2015). Pay, compensation, and performance, psychology of. In International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 611–617). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, J., & De Swart, C. (2013). Financial management in Southern Africa (4th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Mashele, A., Mouton, M., & Pelcher, L. (2024). Corporate governance and financial performance: Family firms vs. non-family firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(10), 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayavo, C. (2023). Towards the development of a sustainable procurement framework for improved operational efficiency in donor-funded procurements in the Zimbabwean public health laboratory services. University of the Witwatersrand. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitnick, B. M. (1975). The theory of agency: A Framework. In The theory of agency (pp. 1–81). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlambo, V., & Spanza, S. (2024). Exploring the challenges of higher education in South Africa: A comprehensive literature review. Alustath Journal for Human and Social Sciences, 63(3), 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubaum, D. O., & Zahra, S. A. (2006). Institutional ownership and corporate social performance: The moderating effects of investment horizon, activism, and coordination. Journal of Management, 32(1), 108–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkwadi, R., & Matemane, M. R. (2022). Executive compensation and company performance: Pre- and post-marikana uprising analysis. Southern African Business Review, 26, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, A., Gosling, T., & Gore, J. (2015). Fairness, envy, guilt and greed: Building equity considerations into agency theory. Human Relations, 68(8), 1291–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PWC. (2020). Practices and remuneration trends report: Executive directors (12th ed., pp. 1–97). PWC. Available online: https://www.pwc.co.za/en/assets/pdf/executive-directors-report-2020.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Ross, S. A., Westerfield, R. W., & Jordan, B. D. (2020). Essentials of corporate finance (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, R. C., Springer, T. M., & Yavas, A. (2005). Conflicts between principals and agents: Evidence from residential brokerage. Journal of Financial Economics, 76(3), 627–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, P. A. (2011). CEO pay-performance sensitivity in South African financial services companies [MBA thesis, University of Pretoria]. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2263/27027 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Shrum, W. (2001). Science and development. In International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 13607–13610). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., Gupta, C. P., & Chaudhary, P. (2024). Defining return on assets (ROA) in empirical corporate finance research: A critical review. Empirical Economics Letters, 23, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz-Urban, C., & Govender, K. K. (2014). The role of professional associations in the South African education and training system. Journal of Social Sciences, 41(2), 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafriadi, E., Sitepu, H. B., Andini, Y. P., Muda, I., & Kesuma, S. A. (2023). The impact of agency theory on organizational behavior: A systematic literature review of the latest research findings. Brazilian Journal of Development, 9(12), 31895–31911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WorldatWork. (2019). Variable pay: Improving performance with variable pay [Graphic]. Available online: https://worldatwork.org/courses/variable-pay-improving-performance-with-variable-pay?tab=virtual (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- WorldatWork. (2021). Total rewards inventory programmes and practices (pp. 1–106). WorldatWork. Available online: https://worldatwork.org/media/CDN/dist/CDN2/documents/pdf/resources/research/WorldatWork_Survey_Total%20Rewards%20Inventory%20Programs%20&%20Practices_2022.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- WorldatWork. (2022). International financial reporting standards for total rewards professions. WorldatWork. [Google Scholar]

- Zinatsa, F., & Saurombe, M. D. (2022). A framework for the labour market integration of female accompanying spouses in South Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 48, a2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maleka, M.J.; Mayavo, C. South Africa’s Vice Chancellors’ Historical and Future Salary Predictors from 2016 to 2026. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100550

Maleka MJ, Mayavo C. South Africa’s Vice Chancellors’ Historical and Future Salary Predictors from 2016 to 2026. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(10):550. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100550

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaleka, Molefe Jonathan, and Crossman Mayavo. 2025. "South Africa’s Vice Chancellors’ Historical and Future Salary Predictors from 2016 to 2026" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 10: 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100550

APA StyleMaleka, M. J., & Mayavo, C. (2025). South Africa’s Vice Chancellors’ Historical and Future Salary Predictors from 2016 to 2026. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(10), 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100550