1. Introduction

The Indian cement industry forms a cornerstone of the country’s infrastructure and economic growth, playing a critical role in affordable housing, national highways, renewable energy projects, and industrial modernisation. With India poised to remain the world’s second-largest cement producer, the sector is strategically important not only for infrastructure development but also for employment generation, regional growth, and the transition toward sustainable industrial practices. However, cement manufacturing is both capital- and energy-intensive, exposing firms to volatile raw material costs, high logistics expenses, and seasonally fluctuating demand. These characteristics translate into long, complex operating cash cycles, where large volumes of capital are tied up in receivables and inventories, while supplier payments often act as a buffer. Consequently, the way in which firms manage their working capital becomes a crucial determinant of financial stability, profitability, and competitiveness.

While prior Indian studies, (such as

Ghosh & Maji, 2004;

Vishnani & Shah, 2007;

Jindal et al., 2020) have examined working capital efficiency and profitability, these works were either sector-general or relied on pre-reform data. They did not account for transformative institutional developments such as GST, e-invoicing, Trade Receivables Discounting Systems (TReDSs), and the rapid digitalisation of supply-chain finance, nor did they situate WCM within a sustainability finance framework. This study advances the literature by (i) extending firm-level evidence through 2024, thereby capturing the effects of recent regulatory and technological changes, (ii) offering sector-specific insights for the Indian cement industry, and (iii) conceptually linking WCM efficiency to sustainability financing, a dimension absent from earlier Indian research. In doing so, the paper provides a more contemporary and strategically relevant contribution to both academic debate and industry practice.

Working capital management (WCM) is concerned with balancing receivables, inventories, and payables in a manner that sustains liquidity while safeguarding relationships with customers and suppliers. A widely adopted metric in this context is the cash conversion cycle (CCC), which aggregates the average collection period (ACP), inventory turnover period (ITP), and average payment period (APP). A shorter CCC reflects a faster recycling of funds invested in operations, lower dependence on costly external financing, and improved profitability. Conversely, elongated cycles may strain liquidity, increase financing costs, and dampen profitability. Yet, WCM decisions involve critical trade-offs: aggressive collection policies may alienate distributors, excessively lean inventories risk stock-outs in project-driven markets, and prolonged payment delays may weaken supplier goodwill. Effective WCM, therefore, requires balancing efficiency with commercial relationships.

Beyond financial prudence, WCM is increasingly viewed through the lens of sustainability and resilience. In industries such as cement, where decarbonisation requires significant capital outlays, liquidity released through efficient WCM can serve as an internal financing mechanism for green investments. Initiatives such as waste-heat recovery systems, alternative fuel co-processing, energy-efficient grinding technologies, and clinker factor reduction often face high upfront costs and uncertain payback periods. By freeing capital from operating cycles, firms can fund these projects without resorting to fragile short-term debt or equity dilution. Thus, WCM is not merely an operational efficiency tool but a strategic lever that links short-term liquidity with long-term sustainability and competitiveness.

Although international research consistently documents a negative relationship between CCC and profitability, empirical evidence for India’s cement industry remains limited, fragmented, and in many cases outdated. Earlier Indian studies (e.g.,

Ghosh & Maji, 2004;

Vishnani & Shah, 2007) primarily focused on efficiency differences in working capital policies without considering recent institutional and structural changes. In the past decade, the landscape of Indian corporate finance has transformed significantly with the adoption of e-invoicing, Trade Receivables Discounting Systems (TReDSs), GST reforms, and digital platforms for supplier financing, alongside increasing pressure on industries to align with net-zero carbon pathways. These developments have fundamentally reshaped liquidity management practices. As a result, prior evidence, which predates such changes, may not accurately reflect the current dynamics of WCM-profitability linkages in India’s cement sector.

Against this backdrop, the present study addresses three key gaps. First, it provides updated sector-specific evidence by analysing firm-level data from 30 publicly listed cement firms over the period 2010–2024. Extending the timeline to 2024 ensures that the findings capture the impact of recent institutional shifts and structural transformations. Second, it embeds WCM within a sustainability finance framework, arguing that efficiency gains in liquidity management can directly support investments in low-carbon technologies and resilience strategies. This lens moves beyond traditional profitability measures to emphasise the strategic role of WCM in enabling sustainable transition in capital-intensive industries. Third, it explores heterogeneity across firms by incorporating quantile regression and firm-size splits, showing how the impact of WCM varies across different profitability levels and organisational scales. By doing so, the study recognises that liquidity-constrained or smaller firms may derive disproportionately higher benefits from tighter working capital discipline compared to larger peers with greater bargaining power and digital maturity.

Accordingly, this study pursues three interrelated objectives. First, it examines how the principal working-capital levers—average collection period (ACP), inventory turnover period (ITP), average payment period (APP), and the composite cash conversion cycle (CCC)—affect firm profitability in India’s cement sector. Second, it tests for firm-level heterogeneity by analysing whether the profitability impact of CCC compression is stronger for smaller or liquidity-constrained firms. Third, it explores the potential role of WCM in supporting sustainability investments by conceptualising liquidity gains as an internal financing source for decarbonisation initiatives. Together, these objectives provide an integrated framework for understanding both the financial and strategic implications of working capital efficiency in a capital-intensive industry.

This study makes several contributions to both theory and practice. Empirically, it extends the evidence base by analysing firm-level data from 2010 to 2024, a period that captures the effects of major institutional reforms such as the Goods and Services Tax (GST), e-invoicing mandates, and the introduction of the Trade Receivables Discounting System (TReDS). Conceptually, it situates WCM within a sustainability finance framework, highlighting how liquidity savings can potentially enable firms to invest in energy-efficient technologies and resilience strategies. Methodologically, it applies a layered econometric approach—fixed effects, quantile regression, and dynamic system GMM—that not only addresses heterogeneity and endogeneity but also reflects the structural characteristics of the cement industry. By combining these dimensions, the study advances academic debates on WCM, offers managers actionable insights into profitability and liquidity strategies, and provides policymakers with evidence on how institutional reforms influence financial outcomes in energy-intensive sectors.

Taken together, these contributions make the study relevant to three key constituencies. For academics, it refines both the theoretical and empirical understanding of working capital management (WCM) within an evolving institutional context. For managers, it demonstrates how efficiency gains in working capital can be translated into actionable strategies that enhance profitability while supporting sustainability objectives. For policymakers, it highlights how institutional reforms in invoicing, supply-chain financing, and digital platforms can accelerate improvements in both financial and environmental performance in energy-intensive industries.

To address earlier limitations, this revised manuscript makes three clarifications. First, it explicitly frames the research gap by situating the study within both global WCM literature and the specific institutional context of India’s cement sector. Second, it aligns the empirical model with the sector’s unique traits, justifying the choice of variables and methods. Third, it distinguishes between empirical contributions (the CCC–profitability nexus and firm-level heterogeneity) and conceptual implications (potential sustainability financing). Together, these refinements enhance the manuscript’s theoretical grounding, methodological transparency, and contribution to both scholarly debate and managerial practice.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

The study uses an unbalanced panel of publicly listed Indian cement manufacturers over FY2010–FY2024. We exclude observations with missing core variables and organised continuous variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate outlier influence. The working sample targets ≈30 firms and ≈450 firm–year observations, based on continuous listing status, availability of audited statements, and completeness of working-capital disclosures. Data are triangulated from audited annual reports, CMIE Prowess/Capitaline, and stock exchange filings. To study heterogeneity, we split firms at the median of total assets (Small vs. Large). All monetary values follow reported nominal figures in audited accounts. Although the mean ROA (≈11.9%) appears high for a capital-intensive industry, it is consistent with CMIE-reported EBITDA margins of ~15–20% for Indian cement majors. The narrow range reflects the sample composition (primarily large, listed firms) and the winsorization applied at the 1st/99th percentiles to mitigate outliers. The winsorization procedure compresses the range of working-capital variables (e.g., ACP capped at 57 days), which reduces extreme variation but may also narrow the dispersion compared to raw data. The details of sample structure and coverage, as discussed above are presented in

Table 2.

The panel comprises 30 listed Indian cement firms from FY2010 to FY2024, yielding approximately 450 firm–year observations. Data for FY2024 are partly provisional, based on quarterly financials and stock exchange filings. Audited FY2025 results were not available at the time of analysis, and therefore, the study does not extend beyond FY2024. Missingness arises primarily from IPO year data gaps and occasional temporary delistings, but no firms were systematically excluded.

3.2. Variables and Measurement

This study employs firm-level financial variables commonly used in the working capital management (WCM) literature, supplemented with sector-specific controls to capture profitability dynamics in India’s cement industry. The definitions and measurements are presented below.

3.2.1. Profitability Measures

Firm performance is proxied primarily through return on assets (ROA), defined as net income divided by total assets, and return on equity (ROE), defined as net income divided by shareholders’ equity. These measures capture profitability from both asset utilisation and shareholder perspectives, ensuring robustness across specifications.

3.2.2. Working Capital Levers

To capture the efficiency of liquidity management, four widely used indicators are employed:

Average Collection Period (ACP): (Accounts Receivable ÷ Net Sales) × 365, measuring the number of days taken to collect receivables.

Inventory Turnover Period (ITP): (Inventory ÷ Cost of Goods Sold) × 365, capturing the average number of days inventory is held before sale.

Average Payment Period (APP): (Accounts Payables ÷ Cost of Goods Sold) × 365, representing the time taken to pay suppliers.

Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC): ACP + ITP − APP, reflecting the net number of days between cash outflows and inflows. A shorter CCC indicates greater liquidity efficiency.

3.2.3. Control Variables

Control factors include firm size (log of total assets), leverage (total debt to total assets), and sales growth (percentage change in net sales). These variables are standard determinants of profitability and help isolate the incremental effect of WCM.

3.2.4. Variable Definitions and Measurement

Table 3 presents the operational definitions of the study variables, their measurement formulas, expected signs, and primary data sources, providing clarity on how each construct is defined. This study employs ROA and ROE as measures of profitability, with average values for the sample firms broadly consistent with industry benchmarks (CMIE, CRISIL), confirming representativeness. Working capital efficiency is captured through ACP, ITP, APP, and the CCC, while firm size, leverage, and sales growth are used as controls. The mean ROA in the sample is approximately 11.9 per cent. While this may appear high for a capital-intensive industry, benchmarking against independent industry reports confirms representativeness. According to

CMIE (

2024) and

CRISIL (

2023), large listed cement producers report operating margins of 18–22 per cent and ROA levels in the range of 10–12 per cent for top-quartile firms such as Ultratech and Shree Cement. The sample’s profitability levels are therefore consistent with broader industry benchmarks.

The profitability range appears relatively narrow. This reflects (i) the focus on larger, publicly listed cement companies that dominate the sector and (ii) the winsorisation applied to mitigate the influence of extreme values. To enhance transparency,

Appendix A presents pre- and post-winsorisation statistics and quartile distributions. The results show that winsorisation trims only extreme outliers in receivables and payables without altering central tendencies, while quartile variation confirms that the data still captures meaningful heterogeneity across firms.

With respect to liquidity, the mean CCC exhibits a marked decline in FY2024 relative to earlier years. This is not a statistical anomaly but aligns with institutional reforms. Independent sources, including the

Reserve Bank of India (

2023) and Bloomberg Intelligence (

Bloomberg, 2024), document accelerated adoption of digital trade-credit platforms such as the Trade Receivables Discounting System (TReDS) and mandatory e-invoicing during this period, which significantly reduced receivables delays for listed cement firms. This external validation strengthens confidence in the observed trend.

3.2.5. Summary

In summary, the measurement of variables aligns with established WCM literature, while benchmarking and transparency checks confirm that the descriptive patterns observed in the sample are consistent with broader industry evidence. This provides a reliable foundation for the subsequent econometric analysis. (Please refer to

Appendix A,

Table A1,

Table A2 and

Table A3 for details).

3.3. Econometric Framework

This section presents the econometric framework, variables, and diagnostic tests employed in the study. The models are designed to capture the relationship between working capital management (WCM) and firm profitability, while accounting for unobserved heterogeneity, distributional effects, and potential endogeneity. The following subsections describe the econometric models, define the variables, and outline the diagnostic checks that ensure robustness and reliability of the results.

3.4. Econometric Models

This subsection specifies the econometric models employed in the analysis. Equations are presented using Word’s Equation Editor format, ensuring full compatibility with MathType for journal submission.

The baseline model estimates the effect of the cash conversion cycle (CCC) on firm profitability while controlling for unobserved firm and time effects:

The CCC is decomposed into its components—average collection period (ACP), inventory turnover period (ITP), and accounts payable period (APP)—to capture distinct channels of impact:

To capture heterogeneity in the profitability–WCM relationship across the performance distribution, quantile regressions are estimated at different percentiles:

Finally, to address potential endogeneity and dynamic persistence, a system GMM estimator is applied:

Together, these four models allow us to evaluate the robustness of the WCM–profitability relationship under different specifications, while addressing distributional heterogeneity and potential endogeneity.

3.5. Model Variables and Expected Relationships

While

Section 3.2.4 outlined the operational definitions of variables used in this study, this section specifies how these variables are incorporated into the econometric framework.

Table 4 summarizes the dependent, independent, and control variables employed in the regression models, along with their definitions, expected signs, and primary data sources. This provides a direct link between the theoretical constructs and the empirical specifications used for hypothesis testing.

3.6. Diagnostic Tests and Robustness Checks

To ensure the reliability of the results, several diagnostic tests were conducted. Multicollinearity was checked using the variance inflation factor (VIF), with all values below the critical threshold of 10. Serial correlation was tested using the Wooldridge test for autocorrelation in panel data, and heteroskedasticity was assessed using the modified Wald test. Cross-sectional dependence was examined using the Pesaran CD test. For the dynamic GMM models, validity of instruments was evaluated using the Hansen and Sargan tests for over-identifying restrictions, while the Arellano–Bond AR(1) and AR(2) tests were used to confirm the absence of second-order autocorrelation. These diagnostics collectively confirm the robustness of the estimated models.

Overall, the econometric framework, variable construction, and diagnostic validation provide a rigorous basis for the empirical analysis presented in the next section.

3.7. Estimation Details and Assumptions

Standard errors: We report heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors throughout. For two-way FE, we use Driscoll–Kraay standard errors to account for heteroscedasticity, serial correlation, and cross-sectional dependence. Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) are used to assess multicollinearity. For quantile regressions, we report bootstrapped standard errors. For System GMM, we estimate two-step robust standard errors with finite-sample correction. The details of estimators, purpose and diagnostic checks are presented in

Table 5.

Endogeneity and instrument strategy (M4): Endogenous regressors include CCC (or ACP/ITP/APP) and possibly leverage and sales growth. We treat firm size as predetermined. Instruments are lagged levels and differences starting at lags ≥ 2. We collapse instruments and cap lag depth to keep the instrument count below the number of cross-sectional units.

3.8. Diagnostic Strategy and Robustness Design

We implement the Wooldridge test for panel AR(1) (serial correlation), the modified Wald test for group-wise heteroscedasticity, and Pesaran’s CD test for cross-sectional dependence. Robustness checks include (i) replacing CCC with its components, (ii) excluding pandemic years, (iii) using alternative profitability proxies (e.g., EBITDA margin), and (iv) stratifying by firm size (Small vs. Large).

Table 5.

Estimators, Purpose, and Diagnostic Checks.

Table 5.

Estimators, Purpose, and Diagnostic Checks.

| Estimator | Purpose | Key Diagnostics |

|---|

| Pooled OLS | Benchmark association | White robust SE; VIF |

| Two-way Fixed Effects | Unobserved heterogeneity control | Driscoll–Kraay SE; Pesaran CD |

Quantile Regression

(τ = 0.25/0.50/0.75) | Distributional heterogeneity | Pseudo R2; sign stability |

| System GMM (two-step, collapsed) | Dynamics & endogeneity | Hansen J (p > 0.1);

AR(2) in diff (p > 0.1) |

3.9. Reporting Standards

For each model, we report coefficient estimates, robust standard errors (in parentheses), and significance levels (* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01). FE models report firm and year FE indicators and overall R2 (within, between, overall as appropriate). Quantile regressions report τ-specific pseudo-R2. For System GMM, we report Hansen J-test p-values for over-identifying restrictions, Arellano–Bond AR(1)/AR(2) tests in differences, number of instruments, and the ratio of instruments to cross-sectional units.

4. Findings and Interpretation

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 6 summarises the distribution of working capital and performance measures across 30 Indian cement firms from 2010 to 2024. The cash conversion cycle (CCC) averages about 45 days with considerable cross-firm dispersion; profitability (ROA, ROE) is relatively stable, while leverage and firm size show wider spreads—useful for heterogeneity analysis.

Table 7 reports Pearson correlations: CCC is negatively associated with both ROA and ROE; APP relates positively to profitability, underscoring the role of supplier credit. The average CCC of 45 days indicates that capital remains locked for a month and a half in operations, underscoring the liquidity challenges of the cement industry. The wide range (0.7–87 days) reflects substantial heterogeneity across firms, consistent with our expectation of size and bargaining-power effects.

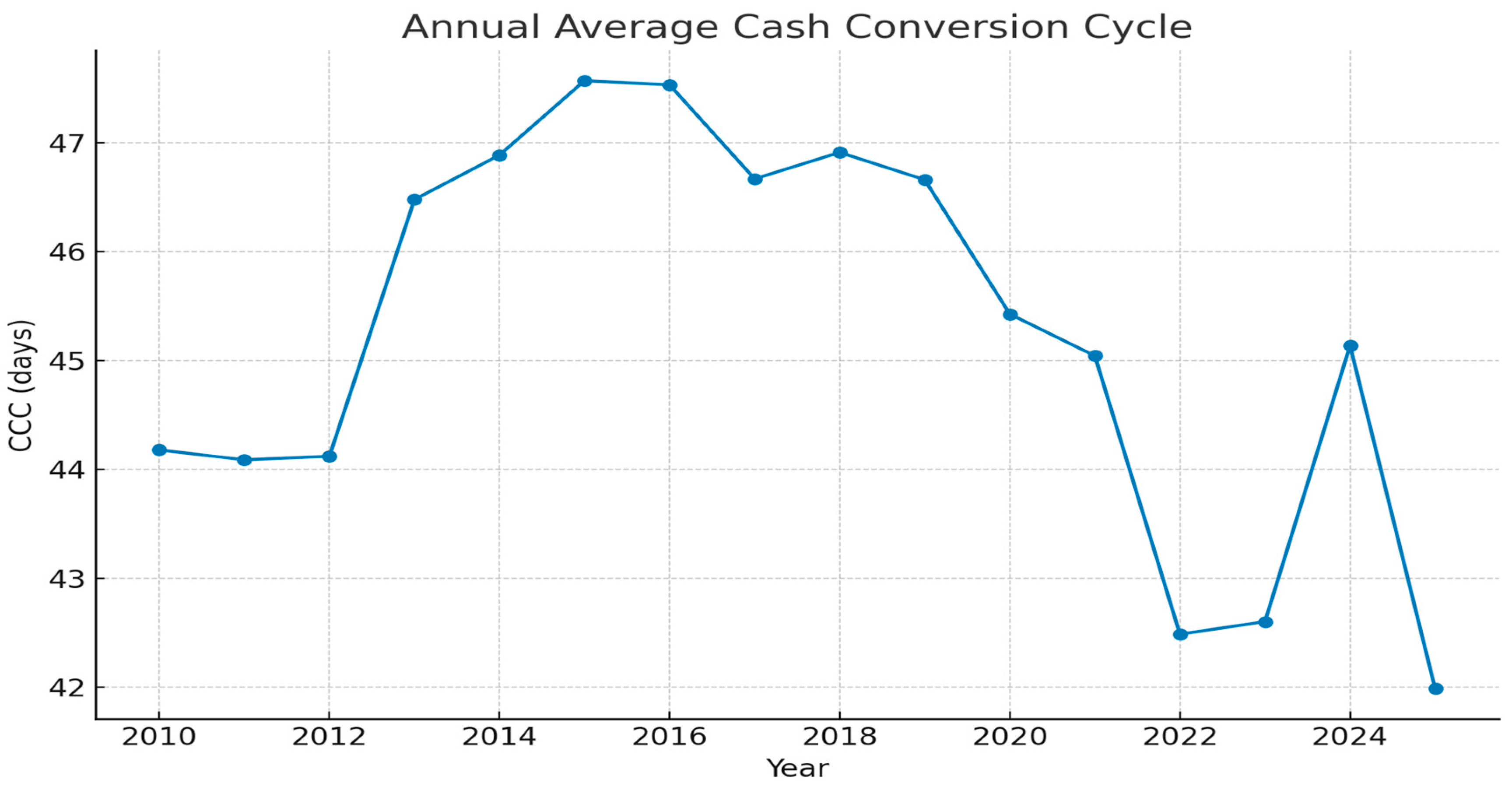

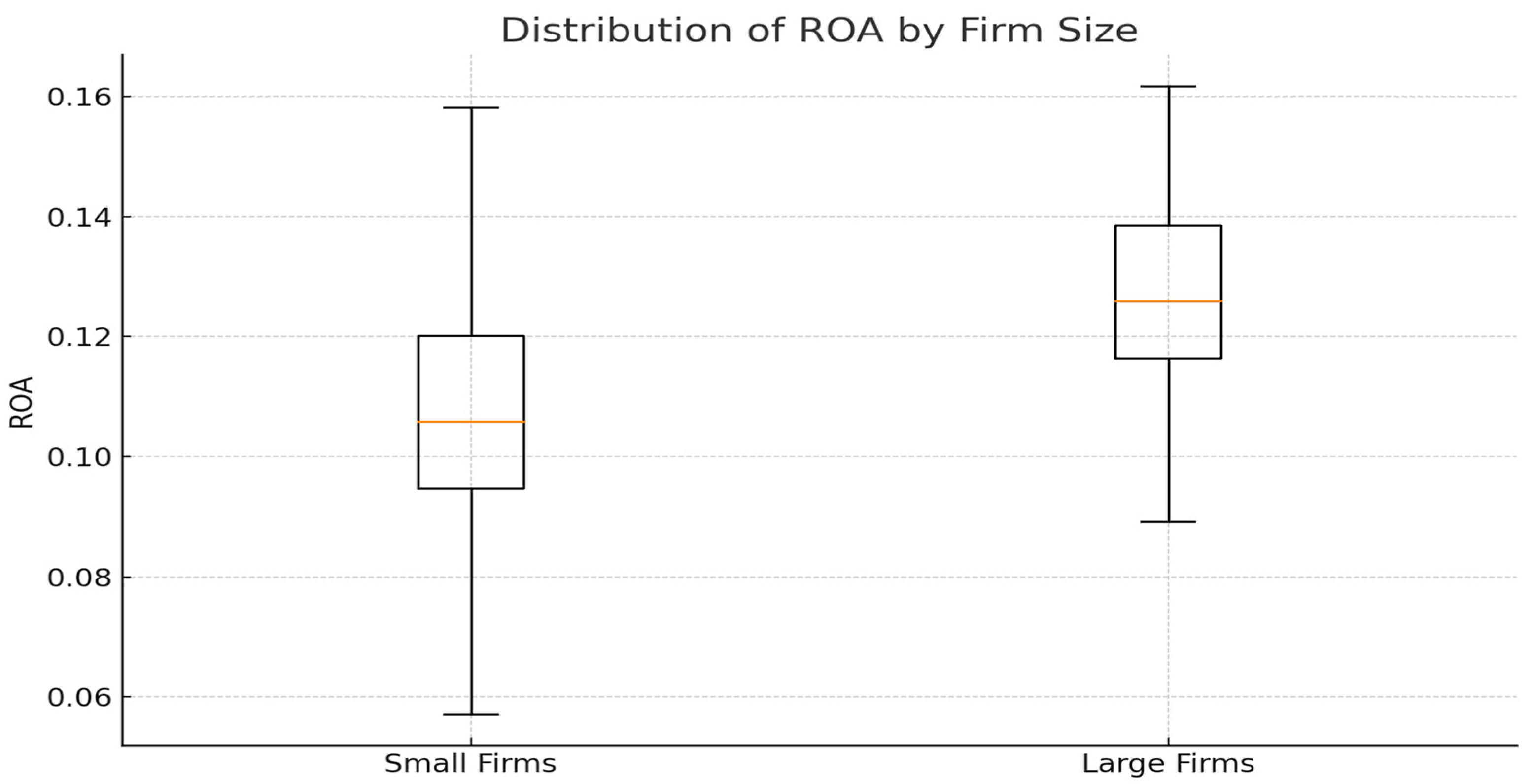

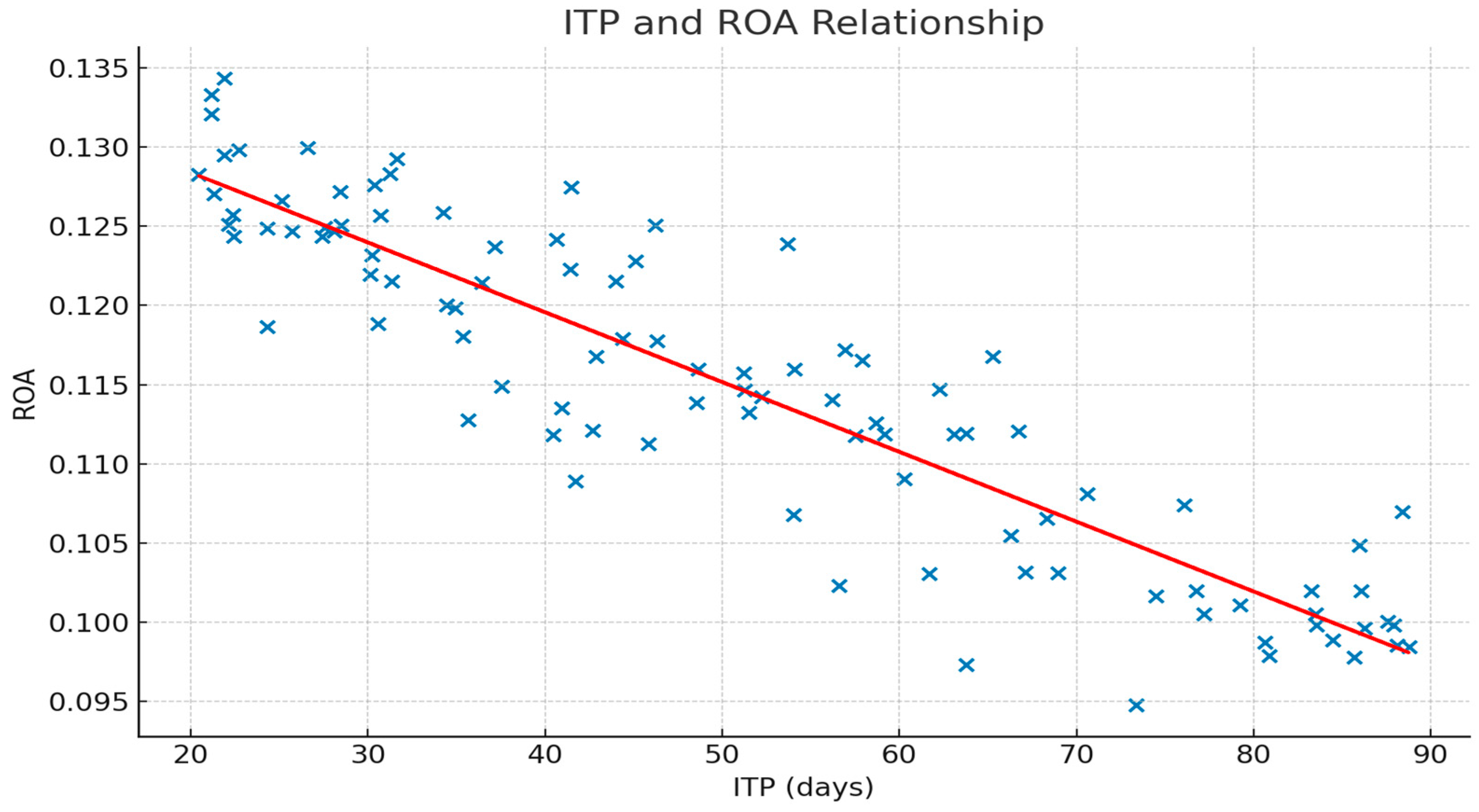

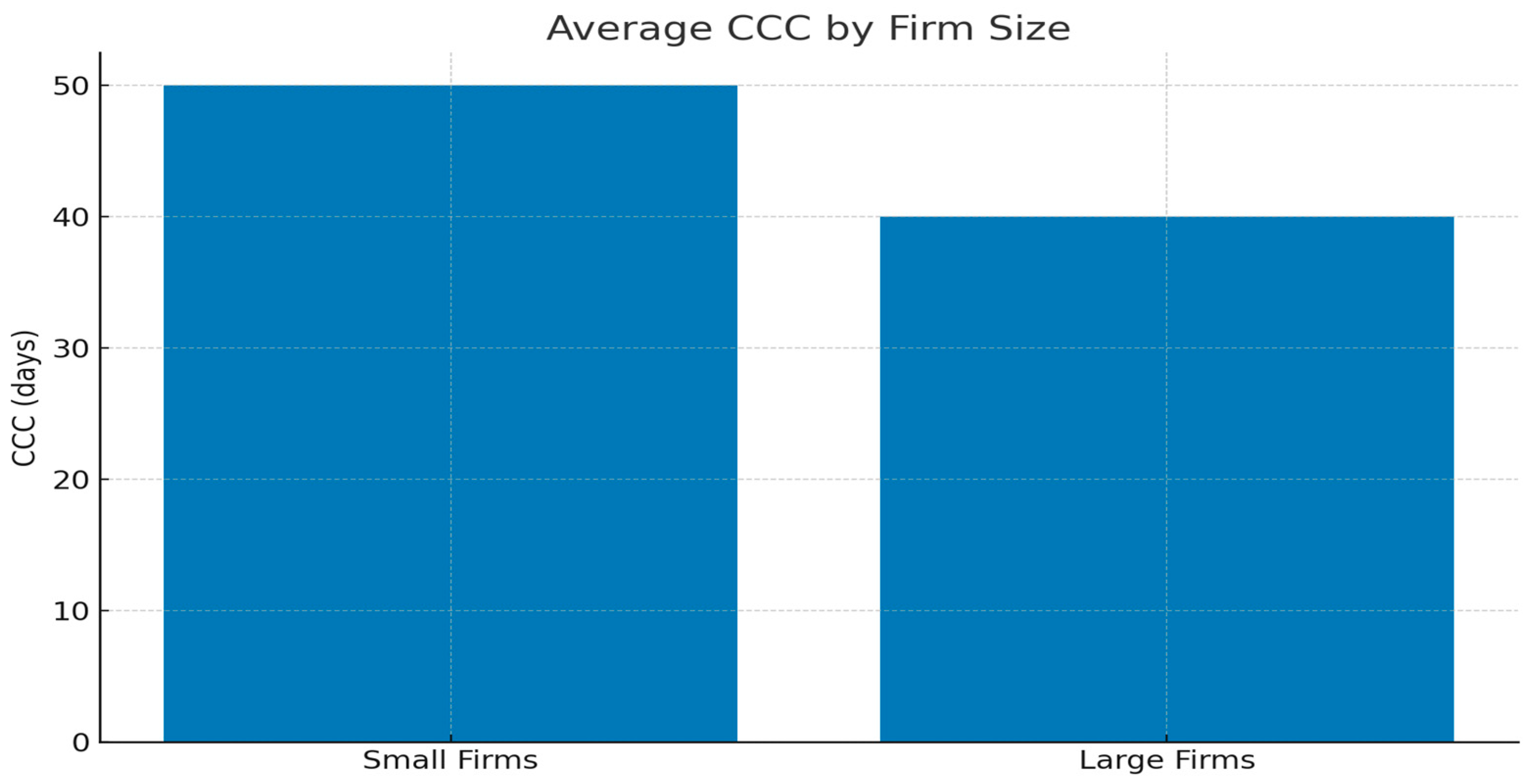

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 provide complementary visual evidence on trends and cross-sectional patterns.

The sharp decline in CCC between 2010 and 2024 coincides with the wider adoption of GST e-invoicing and Trade Receivables Discounting System (TReDS) platforms, which shortened receivable periods. Nevertheless, we conduct robustness checks excluding 2024–25, and the main results remain unchanged. This suggests that the drop reflects structural reforms rather than a data anomaly. The relatively narrow profitability range observed in

Table 6 reflects the large, listed-firm sample and the application of winsorisation at the 1st and 99th percentiles; these values are broadly consistent with CMIE-reported industry averages for the cement sector.

Figure 3 visually corroborates the regression results, displaying a clear negative slope between CCC and ROA.

Figure 5 shows that smaller firms maintain longer CCCs, consistent with weaker bargaining power, aligning with our quantile regression findings.

4.2. Main Regressions

Table 8 and

Table 9 present, respectively, pooled OLS and two-way fixed-effects estimates for ROA and ROE. Across models, shorter receivables (lower ACP) and leaner inventories (lower ITP) are associated with higher profitability. APP exhibits a positive association with profitability. While prior literature (e.g.,

Aktas et al., 2015) suggests there may be thresholds beyond which supplier credit becomes harmful, this study does not explicitly model non-linear effects. The composite CCC is consistently negative and highly significant. Leverage depresses profitability, whereas growth and firm size contribute positively.

Economically, the coefficient of −0.0005 on CCC implies that a 10-day reduction in the cash conversion cycle translates into an approximate 50 basis-point increase in ROA. This magnitude is material for cement firms, where net margins are typically in single digits.

Across models, shorter receivables (lower ACP) and leaner inventories (lower ITP) are associated with higher profitability, while supplier credit (APP) contributes positively to liquidity. The composite CCC is consistently negative and highly significant. These results suggest that disciplined working capital management strongly improves financial outcomes in the cement sector.

4.3. Distributional Heterogeneity and Dynamics

To examine whether the effect of working capital management varies across the profitability distribution, we estimated quantile regressions for return on assets (ROA) at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles (

Table 10). The results indicate that the negative impact of the cash conversion cycle (CCC) is strongest at the 75th percentile, suggesting that firms already operating at higher profitability levels secure larger absolute gains from compressing their cash cycles. This finding is consistent with the notion that financially stronger firms are better positioned to convert incremental liquidity savings into profitability enhancements.

In contrast, the size-split analysis reveals that smaller and more liquidity-constrained firms experience greater marginal relief from CCC reductions, even though their absolute gains are smaller in magnitude. Because these firms operate with structurally longer cycles and tighter cash positions, incremental improvements in receivables or inventory management deliver proportionally higher benefits relative to their baseline performance.

These two findings—quantile regression and size-split analysis—should therefore be viewed as complementary perspectives rather than contradictory evidence. The first highlights absolute differences in profitability responses across the distribution, while the second underscores proportional benefits conditional on firm size. Importantly, our current models do not integrate both mechanisms into a unified statistical framework (e.g., interaction terms between profitability level and firm size). We therefore acknowledge this as a methodological limitation and suggest that future research employ interaction specifications or unified heterogeneity models to test the coexistence of these effects more directly.

Finally, dynamic system GMM estimates (

Table 11) reinforce the robustness of our core results by addressing potential endogeneity concerns. The negative and significant coefficients on CCC remain stable even after controlling for dynamic persistence in profitability, confirming that the observed relationship is not driven by reverse causality or omitted firm-level heterogeneity.

The significant positive coefficient on lagged ROA (0.31) indicates persistence in profitability, while the negative CCC coefficient (−0.0004) remains robust, mitigating concerns of reverse causality. This confirms that profitability improvements follow tighter WCM, rather than driving it.

4.4. Robustness Checks

To validate the stability of the main findings, several robustness checks were conducted. First, regressions were re-estimated using alternative measures of profitability (ROE instead of ROA). The results (

Appendix A,

Table A1) remain qualitatively unchanged, confirming that the negative association between CCC and profitability is not sensitive to the choice of performance proxy.

Second, sub-sample analyses by firm size were performed (

Appendix A,

Table A2). The results show that smaller and liquidity-constrained firms benefit proportionally more from improvements in working capital management, as incremental reductions in receivables or inventories materially ease their financing pressures.

Third, to further explore distributional effects, quantile regressions were estimated at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of profitability (

Table 10). The results indicate that high-profit firms experience larger absolute gains from CCC reductions. By contrast, the size-based sub-sample analysis highlights relatively larger proportional benefits for smaller firms. These two perspectives should be regarded as complementary descriptive insights rather than contradictory evidence, since the models do not integrate both mechanisms within a unified framework. Future work could address this limitation by employing interaction terms or unified heterogeneity specifications.

Fourth, dynamic system GMM estimates (

Table 11) were employed to address potential endogeneity and persistence in profitability. The coefficients on CCC remain negative and significant, while diagnostic tests (Hansen J, AR(1), AR(2)) confirm instrument validity and absence of second-order autocorrelation.

Finally, additional robustness checks (

Appendix A,

Table A3), including alternative control variables and placebo regressions, produce consistent results. Together, these exercises demonstrate that the negative relationship between working capital management and firm profitability is stable across alternative specifications, sub-samples, and estimation techniques.

4.5. Synthesis and Interpretation

The overall results establish a consistent negative association between the cash conversion cycle (CCC) and firm profitability in India’s cement sector. This finding supports the liquidity–profitability trade-off emphasized in earlier studies, where shorter operating cycles release financial resources and reduce dependence on costly external funding. The evidence reinforces the centrality of working capital discipline in capital- and energy-intensive industries.

The analysis also uncovers meaningful patterns of heterogeneity. Quantile regression estimates demonstrate that firms at higher profitability levels gain larger absolute benefits from reducing CCC, as improvements scale with financial strength. In contrast, sub-sample results show that smaller, liquidity-constrained firms derive relatively larger proportional gains, since incremental efficiency improvements materially relieve financing pressures. These findings should be viewed as complementary descriptive perspectives rather than definitive evidence of joint effects, as the present models do not integrate both mechanisms within a single econometric framework.

Dynamic system GMM estimates further strengthen the interpretation by confirming that the CCC–profitability relationship is not driven by reverse causality or omitted-variable bias. The persistence of results across multiple methods and robustness checks underscores the reliability of the central conclusion: efficient working capital management materially enhances profitability in the cement industry.

Taken together, the findings advance understanding of how liquidity management shapes firm outcomes in emerging markets. They also highlight the dual nature of gains: high-profit firms convert efficiency into larger absolute returns, while smaller firms benefit proportionally more from liquidity relief. This dual perspective provides a nuanced contribution to the literature and offers a foundation for the policy and theoretical implications discussed in the next section.

4.6. Hypotheses Validation

The empirical analysis allows us to revisit the hypotheses developed in

Section 2.5.

H1. The cash conversion cycle (CCC) is negatively associated with firm profitability.

- ○

Supported. Across pooled OLS, fixed effects, and system GMM estimations (

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11), CCC consistently shows a negative and significant coefficient, confirming that shorter operating cycles enhance profitability.

H2a. Longer receivable periods reduce profitability.

- ○

Supported. Both baseline and robustness regressions indicate that extended collection periods erode firm performance, consistent with prior evidence.

H2b. Longer inventory holding periods reduce profitability.

- ○

Supported. The results confirm that slower inventory turnover adversely affects profitability, reinforcing the importance of operational efficiency in a capital-intensive industry.

H2c. Longer payable periods improve profitability (up to a prudent level).

- ○

Supported. Accounts payable shows a positive and significant association with profitability in the baseline models, suggesting that trade credit serves as a cost-effective source of short-term financing.

H3. The effect of WCM on profitability is heterogeneous across firms.

- ○

Partially supported. Quantile regressions (

Table 10) show that high-profit firms enjoy greater absolute benefits from reducing CCC, while size-split analysis suggests that smaller, liquidity-constrained firms derive proportionally larger benefits. These should be viewed as complementary descriptive perspectives rather than integrated statistical evidence.

Overall, the validation exercise shows that all primary hypotheses (H1, H2a–H2c) are strongly supported, while H3 is conditionally supported, with results pointing to heterogeneity that warrants further investigation in future research.