Duration of the Membership in the GATT/WTO, Structural Economic Vulnerability and Trade Costs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Discussion

2.1. Membership in the GATT/WTO and the Stability and Predictability of Trading Environment

2.2. Effect of Structural Economic Vulnerability on Trade Costs

2.3. How Can the Duration of GATT/WTO Membership and Structural Economic Vulnerability Interact in Affecting Trade Costs?

3. Model Specification

4. Estimation Strategy

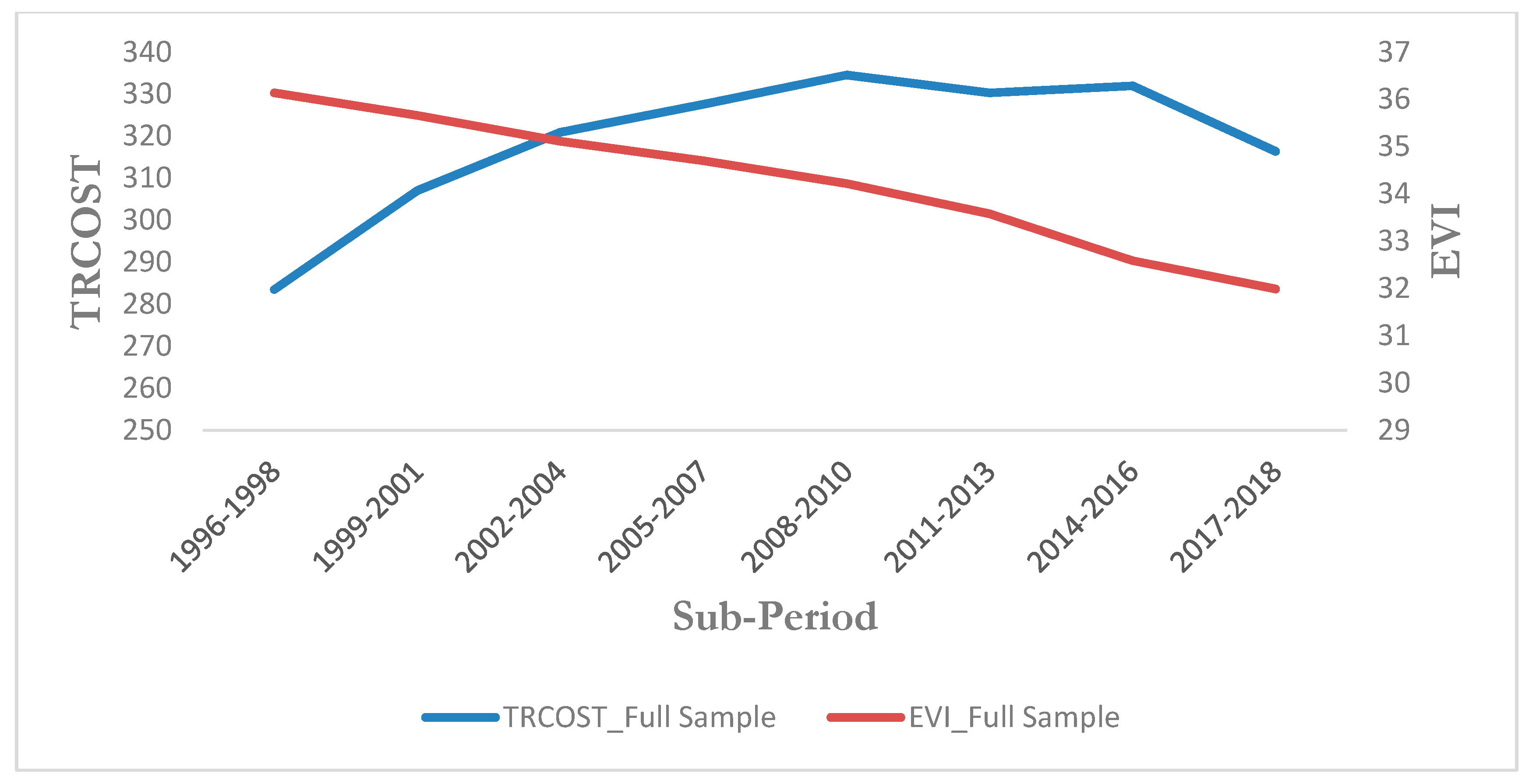

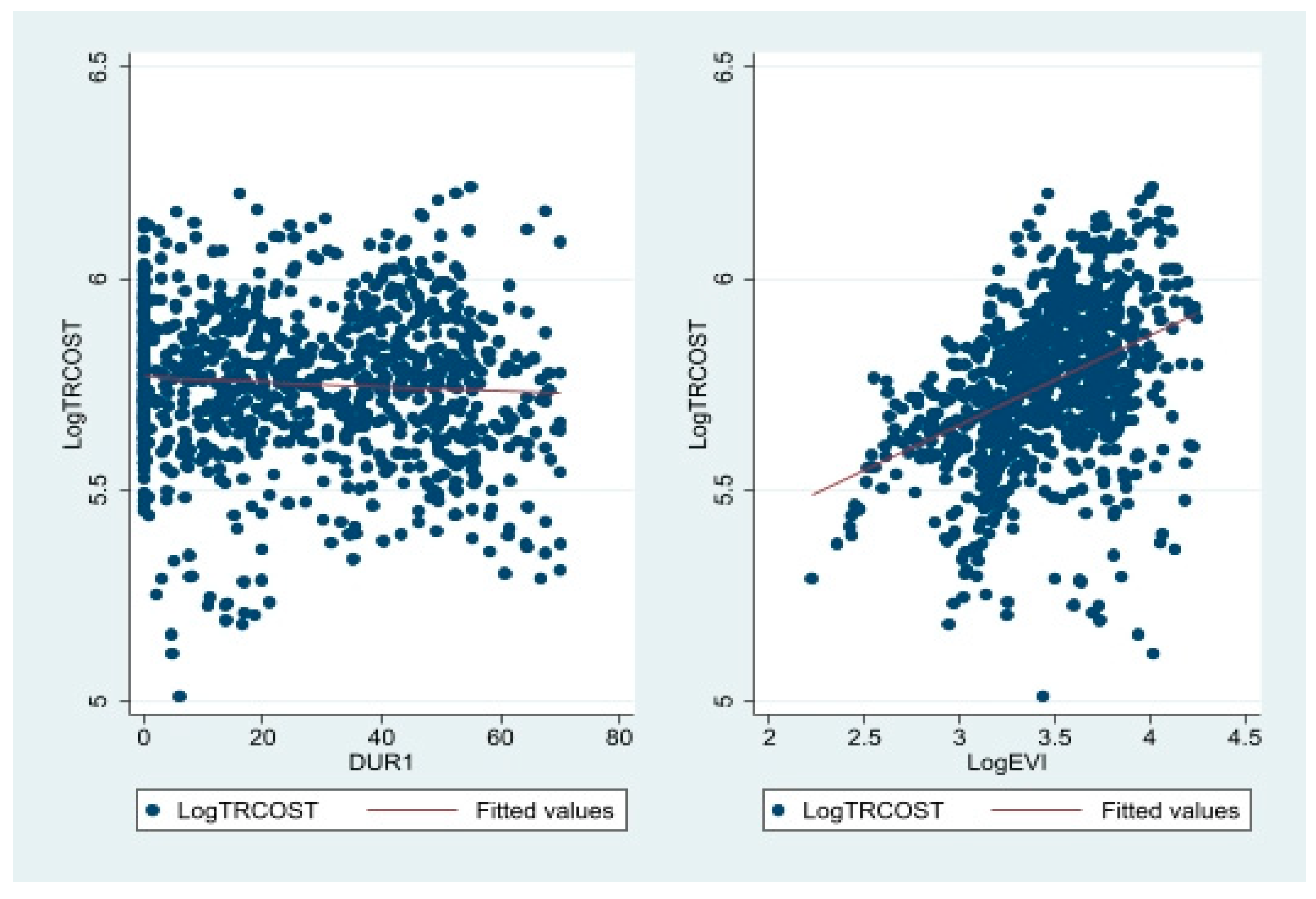

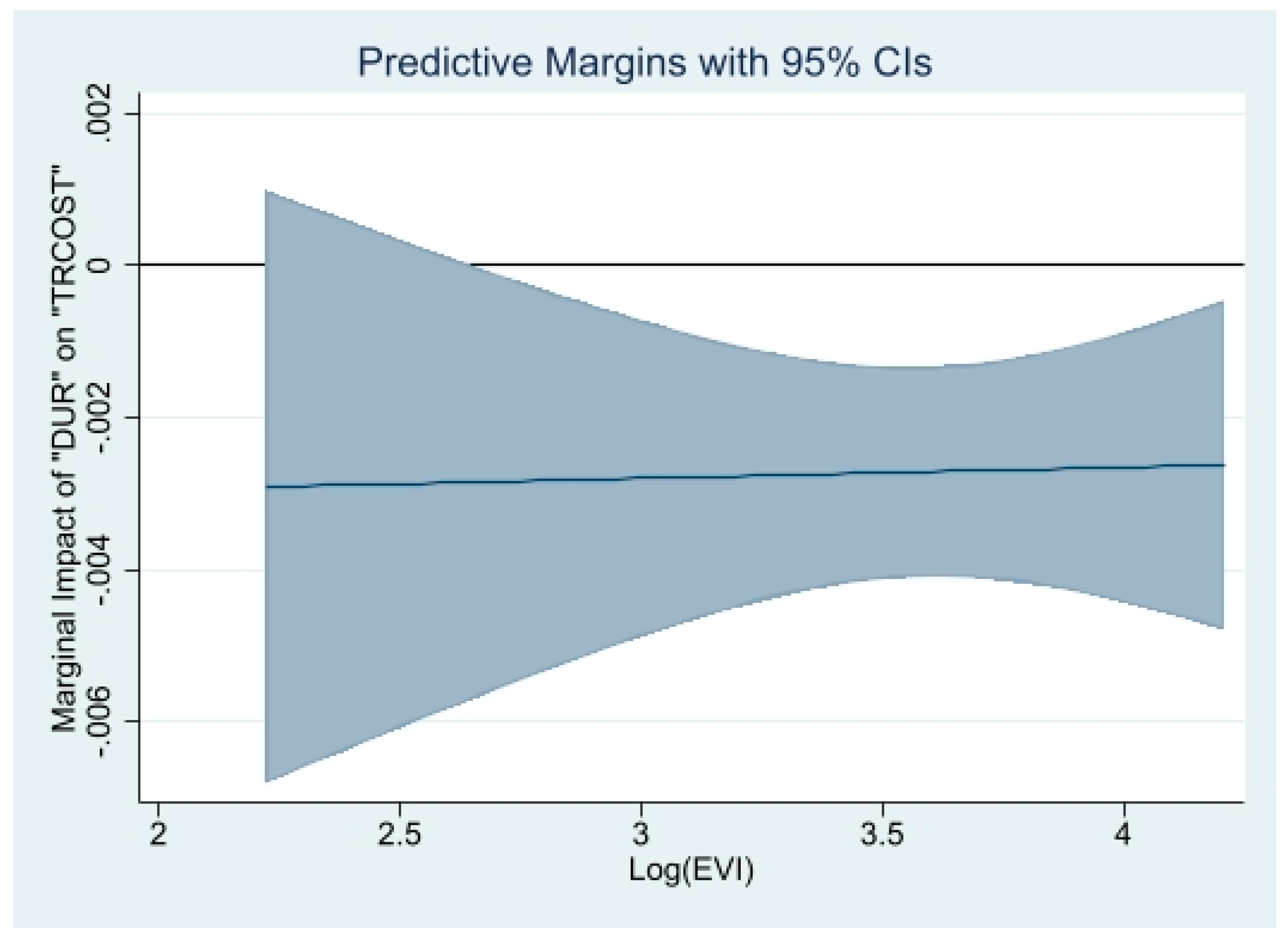

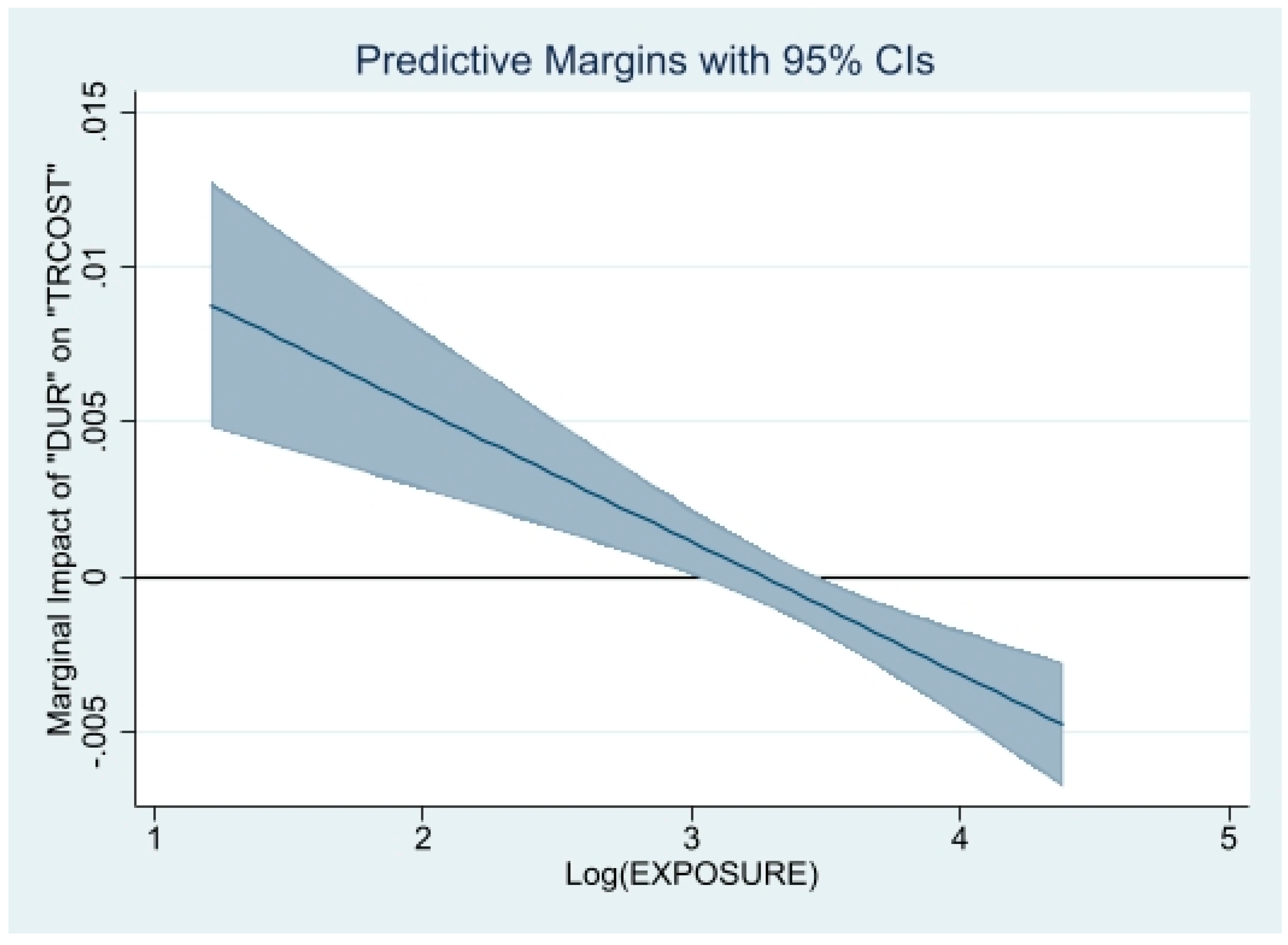

5. Empirical Results

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| TRCOST | This is the indicator of the average comprehensive (overall) trade costs. The average overall trade costs have been calculated for a given country in a given year, as the average of the bilateral overall trade costs on goods across all trading partners of this country. Data on bilateral overall trade costs has been computed by Arvis et al. (2012, 2016) following the approach proposed by Novy (2013). Arvis et al. (2012, 2016) have built on the definition of trade costs by Anderson and van Wincoop (2004) and considered bilateral comprehensive trade costs as all costs involved in trading goods (agricultural and manufactured goods) internationally with another partner (i.e., bilaterally) relative to those involved in trading goods domestically (i.e., intranationally). Hence, the bilateral comprehensive trade costs indicator captures trade costs in its wider sense, including not only tariffs and international transport costs but also other trade cost components discussed in Anderson and van Wincoop (2004), such as direct and indirect costs associated with differences in languages, currencies, and cumbersome import or export procedures. Higher values of the indicator of average overall trade costs indicate higher overall trade costs. | Author’s computation using the ESCAP-World Bank Trade Cost Database. Accessible online at: https://www.unescap.org/resources/escap-world-bank-trade-cost-database (accessed on 1 January 2021). Detailed information on the methodology used to compute the bilateral comprehensive trade costs can be found in Arvis et al. (2012, 2016), as well as in the short explanatory note accessible online at: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/Trade%20Cost%20Database%20-%20User%20note.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2021) |

| TARIFF | This is the indicator of the average tariff costs. It is the tariff component of the average overall trade costs. We have computed it, for a given country in a given year, as the average of the bilateral comprehensive tariff costs across all trading partners of this country. Data on the bilateral tariff costs indicator has been computed by Arvis et al. (2012, 2016). As the bilateral tariff costs indicator is (like the comprehensive trade costs) bi-directional in nature (i.e., it includes trade costs to and from a pair of countries), Arvis et al. (2013) have measured it as the geometric average of the tariffs imposed by the two partner countries on each other’s imports (of agricultural and manufactured goods). Higher values of the indicator of the average tariff costs show an increase in the average tariff costs. | Author’s computation using the ESCAP-World Bank Trade Cost Database. Detailed information on the methodology used to compute the bilateral tariff costs can be found in Arvis et al. (2012, 2016), as well as in the short explanatory note accessible online at: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/Trade%20Cost%20Database%20-%20User%20note.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2021) |

| NTARIFF | This is the indicator of the average nontariff costs. It represents the second component (i.e., nontariff component) of the comprehensive trade costs. This is the indicator of the comprehensive trade costs, excluding the tariff costs. We have computed it, for a given country in a given year, as the average of the bilateral comprehensive nontariff costs (i.e., the comprehensive trade costs, excluding the tariff costs) across all trading partners of this country. Data on the bilateral nontariff costs indicator has been computed by Arvis et al. (2012, 2016), following Anderson and van Wincoop (2004). Comprehensive trade costs excluding tariff encompass all additional costs other than tariff costs involved in trading goods (agricultural and manufactured goods) bilaterally rather than domestically. Higher values of the indicator of average nontariff costs reflect a rise in nontariff costs. Detailed information on the methodology used to compute the bilateral nontariff costs can be found in Arvis et al. (2012, 2016), as well as in the short explanatory note accessible online at: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/Trade%20Cost%20Database%20-%20User%20note.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2021) | Author’s computation using the ESCAP-World Bank Trade Cost Database. Detailed information on the methodology used to compute the bilateral nontariff costs can be found in Arvis et al. (2012, 2016), as well as in the short explanatory note accessible online at: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/Trade%20Cost%20Database%20-%20User%20note.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2021) |

| DUR | This is the indicator of the duration of the GATT/WTO membership. See its description in Section 3. | Author’s computation based on data collected from the website of the WTO. The list of countries (128) that had signed GATT by 1994 is accessible online at: https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/gattmem_e.htm (accessed on 1 January 2021) The list of states that were GATT Members, and that joined the WTO, as well as those that joined the WTO under the WTO’s Article XII is accessible online at: (https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/org6_e.htm (accessed on 1 January 2021)) |

| EVI | This is indicator of structural economic vulnerability, also referred to as the Economic Vulnerability Index. It has been set up at the United Nations by the Committee for Development Policy (CDP), and used by the latter as one of the criteria for identifying LDCs. It has been computed on a retrospective basis for 145 developing countries (including 48 LDCs) by the “Fondation pour les Etudes et Recherches sur le Developpement International (FERDI)”. The EVI has been computed as the simple arithmetic average of two sub-indexes, namely the intensity of exposure to shocks (exposure sub-index) (denoted “EXPOSURE”) and the intensity of exogenous shocks (shocks sub-index) (denoted “SHOCK”). These two sub-indexes have been calculated using a weighted average of different component indexes, with the sum of components’ weights equaling 1 so that the values of EVI range between 0 and 100. For further details on the computation of the EVI, see, for example, Feindouno and Goujon (2016). The components of the exposure sub-index are the population size; the remoteness from world markets index; the export product concentration; the share of agriculture, forestry, and fisheries in GDP; and the index of the share of the population living in low-elevated coastal zones. The components of the shocks sub-index are the agricultural production instability; the export instability; and the index of the victims of natural disasters. | Data on EVI is extracted from the database of the Fondation pour les Etudes et Recherches sur le Developpement International (FERDI)–see online at: https://ferdi.fr/donnees/un-indicateur-de-vulnerabilite-economique-evi-retrospectif (accessed on 1 January 2021) |

| GDPC | Real per capita Gross Domestic Product (constant 2010 USD). | World Development Indicators (WDI) |

| ODA | This is the real gross disbursements of total Official Development Assistance (ODA) expressed in constant prices 2019, US Dollar. | OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) database on development indicators. |

| AfT | This is the indicator of the real gross disbursements of total Aid for Trade. It is the sum of the real gross disbursements of Aid for Trade allocated to the buildup of economic infrastructure, the real gross disbursements of Aid for Trade for building productive capacities, and the real gross disbursements of Aid allocated for trade policy and regulation. All components of total AfT variables are expressed in constant prices 2019, US Dollar. | Author’s calculation based on data extracted from the OECD statistical database on development, in particular the OECD/DAC-CRS (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development/Donor Assistance Committee)-Credit Reporting System (CRS). |

| NonAfT | This is the measure of the development aid allocated to other sectors in the economy than the trade sector. It has been computed as the difference between the gross disbursements of total ODA and the gross disbursements of total Aid for Trade (both being expressed in constant prices 2019, US Dollar). | Author’s calculation based on data extracted from the OECD/DAC-CRS database. |

| TERMS | This is the indicator of terms of trade, measured by the net barter terms of the trade index (2000 = 100). This indicator has been re-scaled (i.e., divided by 100) so that its values range between 0 and 1. | Author’s calculation based on terms of trade data extracted from the WDI. |

| FINDEV | This is the proxy for financial development. It is measured by the share of domestic credit to private sector by banks in GDP (not expressed in percentage). | WDI |

| INST | This is the variable capturing the institutional and governance quality. It has been computed by extracting the first principal component (based on factor analysis) of the following six indicators of governance. These indicators are respectively: political stability and absence of violence/terrorism; regulatory quality; rule of law; government effectiveness; voice and accountability, and corruption. Higher values of the index “INST” are associated with better governance and institutional quality, while lower values reflect worse governance and institutional quality. | Data on the components of “INST” variables has been extracted from World Bank Governance Indicators developed by Kaufmann et al. (2010) and updated recently. See online at: https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/ (accessed on 1 January 2021) |

Appendix B

| Country | Duration of Membership in 2018 | Country | Duration of Membership in 2018 | Country | Duration of Membership in 2018 | Country | Duration of Membership in 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan ** | 2.5 | Cote d’Ivoire | 55.0833 | Lesotho ** | 31 | Senegal | 55.3333 |

| Algeria | 0 | Cyprus | 55.5 | Liberia | 2.5 | Seychelles | 3.75 |

| Angola | 24.75 | Dominica | 25.75 | Madagascar | 55.6667 | Sierra Leone | 57.6667 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 31.8333 | Dominican Republic | 68.6667 | Malawi ** | 54.4167 | Singapore | 45.4167 |

| Argentina | 51.25 | Ecuador | 23 | Malaysia | 61.25 | South Africa | 70.5833 |

| Armenia ** | 15.9167 | Egypt, Arab Rep. | 48.6667 | Maldives | 35.75 | Sri Lanka | 70.5 |

| Azerbaijan ** | 0 | El Salvador | 27.6667 | Mali ** | 26 | St. Kitts and Nevis | 24.8333 |

| Bahamas, The | 0 | Equatorial Guinea | 0 | Mauritania | 55.3333 | St. Lucia | 25.75 |

| Bangladesh | 46.0833 | Eswatini ** | 25.8333 | Mauritius | 48.3333 | St. Vincent and the Grenadines | 25.6667 |

| Barbados | 51.9167 | Fiji | 25.1667 | Mexico | 32.4167 | Sudan | 0 |

| Belize | 35.25 | Gabon | 55.6667 | Micronesia, Fed. Sts. | 0 | Suriname | 40.8333 |

| Benin | 55.3333 | Gambia, The | 53.9167 | Mongolia ** | 22 | Tajikistan ** | 5.83333 |

| Bhutan ** | 0 | Georgia | 18.5833 | Morocco | 31.5833 | Tanzania | 57.0833 |

| Bolivia ** | 28.3333 | Ghana | 61.25 | Mozambique | 26.5 | Thailand | 36.1667 |

| Botswana ** | 31.4167 | Grenada | 24.9167 | Myanmar | 70.5 | Togo | 54.8333 |

| Brazil | 70.5 | Guatemala | 27.25 | Namibia | 26.3333 | Tonga | 11.5 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 25.0833 | Guinea | 24.0833 | Nepal ** | 14.75 | Trinidad and Tobago | 56.25 |

| Burkina Faso ** | 55.6667 | Guyana | 52.5 | Nicaragua | 68.6667 | Tunisia | 28.4167 |

| Burundi ** | 53.8333 | Honduras | 24.75 | Niger ** | 55.0833 | Turkey | 67.25 |

| Cabo Verde | 10.5 | India | 70.5 | Nigeria | 58.1667 | Uganda ** | 56.25 |

| Cambodia | 14.25 | Indonesia | 68.9167 | Oman | 18.1667 | Uruguay | 65.0833 |

| Cameroon | 55.6667 | Iran, Islamic Rep. | 0 | Pakistan | 70.5 | Uzbekistan ** | 0 |

| Central African Republic ** | 55.6667 | Iraq | 0 | Panama | 21.6667 | Vanuatu | 6.41667 |

| Chad ** | 55.5 | Israel | 56.5 | Papua New Guinea | 24.0833 | Venezuela, RB | 28.4167 |

| Chile | 69.8333 | Jamaica | 55.0833 | Paraguay ** | 25 | Vietnam | 12 |

| China | 17.0833 | Jordan | 18.75 | Peru | 67.25 | Yemen, Rep. | 4.58333 |

| Colombia | 37.25 | Kazakhstan ** | 3.16667 | Philippines | 39.0833 | Zambia ** | 36.9167 |

| Comoros | 0 | Kenya | 54.9167 | Rwanda ** | 53 | Zimbabwe ** | 70.5 |

| Congo, Dem. Rep. | 47.3333 | Kyrgyz Republic ** | 20.0833 | Samoa | 6.66667 | ||

| Congo, Rep. | 55.6667 | Lao PDR ** | 5.91667 | Sao Tome and Principe | 0 | ||

| Costa Rica | 28.1667 | Lebanon | 0 | Saudi Arabia | 13.0833 |

Appendix C

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRCOSTS | 582 | 330.691 | 56.527 | 150.240 | 500.805 |

| TARIFF | 557 | 1.100 | 0.024 | 1.047 | 1.208 |

| NONTARIFF | 557 | 287.006 | 52.638 | 128.532 | 433.378 |

| DUR1 | 582 | 30.285 | 21.146 | 0 | 70.083 |

| EVI | 582 | 34.002 | 11.528 | 9.224 | 70.045 |

| EXPOSURE | 582 | 35.262 | 13.551 | 3.352 | 79.036 |

| SHOCK | 582 | 32.745 | 15.217 | 4.378 | 87.964 |

| ODA | 582 | 661 | 1010 | 0.16 | 15,300 |

| AfT | 576 | 206 | 378 | 0.05333433 | 3640 |

| NonAfT | 576 | 637 | 901 | 2.419856 | 12,400 |

| FINDEV | 582 | 0.346 | 0.275 | 0.008 | 1.518 |

| TERMS | 582 | 1.221 | 0.419 | 0.281 | 4.537 |

| INST | 582 | −0.945 | 1.533 | −4.264 | 3.666 |

| GDPC | 582 | 4464.304 | 4858.752 | 212.472 | 36,938.410 |

| 1 | The WTO Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement (see WTO 2012) is available online at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tbt_e/tbt_e.htm (accessed on 1 January 2021). |

| 2 | The WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures is available online at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/sps_e/spsagr_e.htm (accessed on 1 January 2021). |

| 3 | Nontariff border measures are increasingly used to regulate trade at a time when the ghost of protectionism looms large across the world economy (e.g., Cha and Koo 2021), notably in high-income countries (e.g., Cha and Koo 2021; Hoekman and Nicita 2011). |

| 4 | These include, for example, tariffs and other explicit and implicit border taxes, such as those associated with stringent and costly customs procedures. |

| 5 | See, for example, Ali and Milner (2016); Gaurav and Mathur (2016); Hummels (2007); Jacks et al. (2008, 2011); Milner and McGowan (2013); Novy (2013); Papalia and Bertarelli (2015); and Shepherd (2022). |

| 6 | Further details on the fulfilment of the transparency objective by WTO Councils and Committees are available online at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/monitor_e/monitor_e.htm (accessed on 1 January 2021). |

| 7 | Further information on the WTO’s role of overseeing national trade policies is available online at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tpr_e/tp_int_e.htm (accessed on 1 January 2021). |

| 8 | These shocks include, for example, commodity prices shocks, shocks to international export demand; capital flow reversals; natural disasters (droughts, earthquakes, pandemics, extreme temperatures, storms, hurricanes, volcanoes); and potentially domestic political shocks. |

| 9 | Knight (1921) has defined uncertainty as the inability of people to forecast the likelihood of the occurrence of events. This, therefore, refers to a situation where economic agents are not capable of predicting the likely state of the economy in the future. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic has generated high uncertainty in economies severely affected by this crisis in the world. According to Abel (1983), economic uncertainty can refer to unexpected changes that affect the economic ecosystem, and how changes in fiscal or monetary policies or any other government policies affect corporations. |

| 10 | See, for example, Azomahou et al. (2021), Barrot et al. (2018), Dabla-Norris and Gündüz (2014), Kim et al. (2020), and Raddatz (2007). |

| 11 | The category of LDCs was first established (by the United Nations General Assembly) in 1971. Information on this group of countries is accessible online at: https://www.un.org/ohrlls/content/ldc-category (accessed on 1 January 2021). |

| 12 | See, for example, Chowdhury et al. (2021); Koopman et al. (2020), and Mansfield and Reinhardt (2008). |

| 13 | The transparency provisions embedded in WTO agreements require that member states disclose their trade regulations and notify changes to these regulations (e.g., Chowdhury et al. 2021). Basic information on the role of the Trade Policy Review Mechanism concerning “transparency” can be found online at: https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/agrm11_e.htm (accessed on 1 January 2021). |

| 14 | See further information online at: https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/29-tprm.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2021). |

| 15 | “DSU” refers to the Dispute Settlement Understanding of the WTO. The legal text of the DSU is accessible online at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/dsu_e.htm (accessed on 1 January 2021) |

| 16 | Detailed information on the TFA is available online at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tradfa_e/tradfa_e.htm (accessed on 1 January 2021). |

| 17 | Beverelli et al. (2015) and Hoekman and Shepherd (2015) have provided a literature review on the trade costs effect of soft trade facilitation, including the WTO trade facilitation. |

| 18 | This could include the liberalization of their trade policies, i.e., both tariff and nontariff border barriers, as well as the improvement of beyond-the-border trade facilitation policies. |

| 19 | See, for example, Aguiar and Gopinath (2007); Cariolle et al. (2016); Essers (2013); Guillaumont (2009, 2010); and Koren and Tenreyro (2007). |

| 20 | Uncertainty is significantly higher in developing countries than in advanced economies (e.g., Ahir et al. 2019). |

| 21 | Policy uncertainty refers to the economic risk associated with undefined future government policies and regulatory frameworks (e.g., Al-Thaqeb and Algharabali 2019). |

| 22 | See, for example, Colon et al. (2019); Doll et al. (2014); Friedt (2021); Gassebner et al. (2010); Oh (2017); Osberghaus (2019); UNECE (2020); and Martincus and Blyde (2013). |

| 23 | An increase in the value of “DURWTO1” by one year represents a rise in the value of this indicator by 100%. |

References

- Aaronson, Susan Ariel, and M. Rodwan Abouharb. 2014. Does the WTO help member states improve governance? World Trade Review 13: 547–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, Andrew B. 1983. Optimal investment under uncertainty. The American Economic Review 73: 228–33. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, Mark, and Gita Gopinath. 2007. Emerging Markets Business Cycles: The Cycle is the Trend. Journal of Political Economy 115: 11–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahir, Hites, Nicholas Bloom, and Davide Furceri. 2019. The World Uncertainty Index. SIEPR Working Paper No. 19–027. Stanford: Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR). [Google Scholar]

- Alda, Erik, and Jose Cuesta. 2019. Measuring the efficiency of humanitarian aid. Economics Letters 183: 108618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Salamat, and Chris Milner. 2016. Narrow and Broad Perspectives on Trade Policy and Trade Costs: How to Facilitate Trade in Madagascar. The World Economy 39: 1917–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Borrego, César, and Manuel Arellano. 1999. Symmetrically normalized instrumental-variable estimation using panel data. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 17: 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Thaqeb, Saud Asaad, and Barrak Ghanim Algharabali. 2019. Economic policy uncertainty: A literature review. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries 20: e00133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiti, Mary, and David E. Weinstein. 2011. Exports and Financial Shocks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126: 1841–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, James, and Douglas Marcouiller. 2002. Insecurity and the pattern of trade: An empirical investigation. Review of Economics and Statistics 84: 342–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, James E., and Eric van Wincoop. 2004. Trade Costs. Journal of Economic Literature 42: 691–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, Manuel, and Olympia Bover. 1995. Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error components models. Journal of Econometrics 68: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvis, Jean-François, Y. Duval, Ben Shepherd, and Chorthip Utoktham. 2012. Trade Costs in the Developing World: 1995–2010. ARTNeT Working Papers, No. 121/December 2012 (AWP No. 121). Bangkok: Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade, Bangkok, ESCAP. [Google Scholar]

- Arvis, Jean-François, Yann Duval, Ben Shepherd, and Chorthip Utoktham. 2013. Trade Costs in the Developing World: 1995–2010. Available online: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/1813-9450-6309 (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Arvis, Jean-François, Yann Duval, Ben Shepherd, Chorthip Utoktham, and Anasuya Raj. 2016. Trade Costs in the Developing World: 1996–2010. World Trade Review 15: 451–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azomahou, Théophile T., Njuguna Ndung’u, and Mahamady Ouédraogo. 2021. Coping with a dual shock: The economic effects of COVID-19 and oil price crises on African economies. Resources Policy 72: 102093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrot, Luis-Diego, César Calderón, and Luis Servén. 2018. Openness, specialization, and the external vulnerability of developing countries. Journal of Development Economics 134: 310–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, Sudip Ranjan, Victor Ognivtsev, and Miho Shirotori. 2008. Building Trade-Relating Institutions and WTO Accession. Policy Issues in International Trade and Commodities Study Series No. 41. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers, Eddy, and Roberts B. Koopman. 2022. Simulating the trade effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: Scenario analysis based on quantitative trade modelling. The World Economy 45: 445–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverelli, Cosimo, Simon Neumueller, and Robert Teh. 2015. Export Diversification Effects of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement. World Development 76: 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, Nicholas. 2014. Fluctuations in Uncertainty. Journal of Economic Perspectives 28: 153–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, and Stephen Bond. 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, Stephen R. 2002. Dynamic panel data models: A guide to micro data methods and practice. Portuguese Economic Journal 1: 141–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, Stephen, Anke Hoeffler, and Jonathan Temple. 2001. GMM Estimation of Empirical Growth models. CEPR Paper DP3048. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Briguglio, Lino, Gordon Cordina, Nadia Farrugia, and Stephanie Vella. 2009. Economic Vulnerability and Resilience: Concepts and Measurements. Oxford Development Studies 37: 229–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, Matthias, Ruth Hoekstra, and Jens Königer. 2012. The impact of aid for trade facilitation on the costs of trading. Kyklos 65: 143–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calì, Massimiliano, and Dirk Willem te Velde. 2011. Does aid for trade really improve trade performance? World Development 39: 725–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Vinh T. H., and Lisandra Flach. 2015. The Effect of GATT/WTO on Export and Import Price Volatility. The World Economy 38: 2049–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariolle, Joël, Michaël Goujon, and Patrick Guillaumont. 2016. Has Structural Economic Vulnerability Decreased in Least Developed Countries? Lessons Drawn from Retrospective Indices. The Journal of Development Studies 52: 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Yoojin, and Min Gio Koo. 2021. Who Embraces Technical Barriers to Trade? The Case of European REACH Regulations. World Trade Review 20: 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisse, Julien, and Mitsuo Matsushita. 2013. Maintaining the WTO’s Supremacy in the International Trade Order: A Proposal to Refine and Revise the Role of the Trade Policy Review Mechanism. Journal of International Economic Law 16: 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, Thomas. 2016. Liquidity Constrained Exporters. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 72: 141–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvet, Lisa, and Patrick Guillaumont. 2009. Aid, Volatility, and Growth Again: When Aid Volatility Matters and When it Does Not? Review of Development Economics 13: 452–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Hong, and Baljeet Singh. 2020. Effectiveness of Foreign Development Assistance in Mitigating Natural Disasters’ Impact: Case Study of Pacific Island Countries. ADBI Working Paper 1076. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, Abdur, Xuepeng Liu, Miao Wang, and M. C. S. Wong. 2021. The Role of Multilateralism of the WTO in International Trade Stability. World Trade Review 20: 668–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Ximena, David Dollar, and Alejandro Micco. 2004. Port efficiency, maritime transport costs and bilateral trade. Journal of Development Economics 75: 417–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Williams, Terry, and Robert Wolfe. 2010. Transparency as a trade policy tool: The WTO’s cloudy windows. World Trade Review 9: 551–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colon, Colon, Stéphane Hallegatte, and Julie Rozenberg. 2019. Transportation and Supply Chain Resilience in the United Republic of Tanzania: Assessing the Supply-Chain Impacts of Disaster-Induced Transportation Disruptions. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Cordina, Gordon. 2004. Economic Vulnerability and Economic Growth: Some Results from a Neo-Classical Growth Modelling Approach. Journal of Economic Development 29: 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dabla-Norris, Era, and Yasemin Bal Gündüz. 2014. Exogenous Shocks and Growth Crises in Low-Income Countries: A Vulnerability Index. World Development 59: 360–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, Jaime, and Laurent Wagner. 2016. Aid for Trade and the Trade Facilitation Agreement: What They Can Do for LDCs. Journal of World Trade 50: 935–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, Claus, Stefan Klug, and Ricardo Enei. 2014. Large and Small Numbers: Options for Quantifying the Costs of Extremes on Transport Now and in 40 years. Natural Hazards 72: 211–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabek, Zdenek, and Marc Bacchetta. 2004. Tracing the Effects of WTO Accession on Policymaking in Sovereign States: Preliminary Lessons from the Recent Experience of Transition Countries. The World Economy 27: 1083–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, Pushan. 2020. The WTO is not passé. European Economic Review 128: 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, Pushan, Ilian Mihov, and Timothy Van Zandt. 2013. The effect of WTO on the extensive and the intensive margins of trade. Journal of International Economics 91: 204–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliason, Antonia. 2015. The Trade Facilitation Agreement: A New Hope for the World Trade Organization. World Trade Review 14: 643–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essers, Dennis. 2013. Developing country vulnerability in light of the global financial crisis: Shock therapy? Review of Development Finance 3: 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajgelbaum, Pablo D., Mathieu Taschereau-Dumouchel, and Edouard Schaal. 2017. Uncertainty Traps. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132: 1641–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feindouno, Sosso, and Michaël Goujon. 2016. The Retrospective Economic Vulnerability Index, 2015 Update. Working Paper n°147. Clermont-Ferrand: Fondation pour les Etudes et Recherches sur le Developpement InternationaL (FERDI). [Google Scholar]

- Felbermayr, Gabriel, and Wilhelm Kohler. 2010. Does WTO Membership Make a Difference at the Extensive Margin of World Trade? In Is the World Trade Organization Attractive Enough for Emerging Economies? Edited by Drabek Z. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, C. Fritz, and Kalina Manova. 2015. International Trade, Multinational Activity, and Corporate Finance. Annual Review of Economics 7: 119–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedt, Felix L. 2021. Natural Disasters, Aggregate Trade Resilience, and Local Disruptions: Evidence from Hurricane Katrina. Review of International Economics 29: 1081–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassebner, Martin, Alexander Keck, and Robert Teh. 2010. Shaken, Not Stirred: The Impact of Disasters on International Trade. Review of International Economics 18: 351–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, Abhishek, and Somesh K. Mathur. 2016. Determinants of Trade Costs and Trade Growth Accounting between India and the European Union during 1995–2010. The World Economy 39: 1399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sena Kimm. 2018. Aid for trade and trade policy in recipient countries. The International Trade Journal 32: 439–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sena Kimm. 2021. Productive Capacities, Economic Growth and Economic Growth Volatility in Developing Countries: Does Structural Economic Vulnerability Matter? Journal of International Commerce, Economics and Policy, 2550001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, Andrew. 2014. The WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement: Consulting the Private Sector. Journal of World Trade 48: 1167–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppo, Valeria, and Roberta Piermartini. 2014. Trade Policy Uncertainty and WTO. WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2014–23, WTO. Geneva: World Trade Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaumont, Patrick. 2009. An Economic Vulnerability Index: Its Design and Use for International Development Policy. Oxford Development Studies 37: 193–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaumont, Patrick. 2010. Assessing the Economic Vulnerability of Small Island Developing States and the Least Developed Countries. The Journal of Development Studies 46: 828–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaumont, Patrick, and Laurent Wagner. 2012. Aid and Growth Accelerations: Vulnerability Matters. UNU-WIDER Working Paper Series WP-2012-031; Helsinki: UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). [Google Scholar]

- Heckelei, Thomas, and Johan Swinnen. 2012. Introduction to the Special Issue of the World Trade Review on ‘standards and non-tariff barriers in trade. World Trade Review 11: 353–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, Bernard, and Alessandro Nicita. 2010. Assessing the Doha Round: Market Access, Transactions Costs and Aid for Trade Facilitation. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development 19: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, Bernard, and Alessandro Nicita. 2011. Trade policy, trade costs and developing country trade. World Development 39: 2069–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, Bernard, and Ben Shepherd. 2015. Who profits from trade facilitation initiatives? Implications for African countries. Journal of African Trade 2: 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Yulin, Yun Wang, and Wenjun Xue. 2021. What explains trade costs? Institutional quality and other determinants. Review of Development Economics 25: 478–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummels, David. 2007. Transport costs and international trade in the second era of globalisation. Journal of Economic Perspectives 21: 131–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilut, Cosmin, and Hikaru Saijo. 2021. Learning, confidence, and business cycles. Journal of Monetary Economics 117: 354–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organization. 2017. Making trade an Engine of Growth for All: The Case for Trade and for Policies to Facilitate Adjustment. Prepared for discussion at the March 2017 Meeting of G20 Sherpas by Staffs of the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organization. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Jacks, David S., Christopher M. Meissner, and Dennis Novy. 2008. Trade costs, 1870–2000. American Economic Review 98: 529–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacks, David S., Christopher M. Meissner, and Dennis Novy. 2011. Trade booms, trade busts and trade costs. Journal of International Economics 83: 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubik, Adam, and Roberta Piermartini. 2019. How WTO commitments tame uncertainty. In WTO Staff Working Papers ERSD-2019-06. Geneva: World Trade Organization (WTO). [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2010. The Worldwide Governance Indicators Methodology and Analytical Issues. World Bank Policy Research N° 5430 (WPS5430). Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Youngju, Hyunjoon Lim, and Wook Sohn. 2020. Which external shock matters in small open economies? Global risk aversion vs. US economic policy uncertainty. Japan and the World Economy 54: 101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Frank H. 1921. Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. Boston: Hart, Schaffner, and Marx. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, David, Fernando Leibovici, and Michal Szkup. 2016. Financial Frictions and New Exporter Dynamics. International Economic Review 57: 453–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, Robert, John Hancock, Roberta Piermartini, and Eddy Bekkers. 2020. The Value of the WTO. Journal of Policy Modeling 42: 829–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, Miklós, and Silvana Tenreyro. 2007. Volatility and Development. Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 243–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hyun-Hoon, Donghyun Park, and Meehwa Shin. 2015. Do Developing-country WTO Members Receive More Aid for Trade (AfT)? The World Economy 38: 1462–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibovici, Fernando. 2021. Financial Development and International Trade. Journal of Political Economy 129: 3405–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, Nils-Gustav. 1996. Bulk Trade and Maritime Transport Costs: The Evolution of Global Markets. Resources Policy 22: 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manova, Kalina. 2013. Credit Constraints, Heterogeneous Firms, and International Trade. Review of Economic Studies 80: 711–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, Edward, and Eric Reinhardt. 2008. International Institutions and the Volatility of International Trade. International Organization 62: 621–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martincus, Christian Volpe, and Juan Blyde. 2013. Shaky roads and trembling exports: Assessing the trade effects of domestic infrastructure using a natural experiment. Journal of International Economics 90: 148–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, Sébastien, and Ashok K. Mishra. 2020. Humanitarian food aid and civil conflict. World Development 126: 104713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, Chris, and Danny McGowan. 2013. Trade costs and trade composition. Economic Inquiry 51: 1886–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minetti, Raoul, and Susan Chun Zhu. 2011. Credit constraints and firm export: Microeconomic evidence from Italy. Journal of International Economics 83: 109–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moïsé, Evdokia, and Silvia Sorescu. 2013. Trade Facilitation Indicators: The Potential Impact of Trade Facilitation on Developing Countries’ Trade. OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 144. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Moïsé, Evdokia, Thomas Orliac, and Peter Minor. 2012. Trade Facilitation Indicators: The Impact on Trade Costs. OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 118. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nickell, Stephen. 1981. Biases in Dynamic Models with Fixed Effects. Econometrica 49: 1417–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy, Dennis. 2013. Gravity redux: Measuring international trade costs with panel data. Economic Inquiry 51: 101–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/WTO. 2015. Aid for Trade at a Glance 2015: Reducing Trade Costs for Inclusive, Sustainable Growth. Paris: WTO. Geneva: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Chang Hoon. 2017. How Do Natural and Man-made Disasters Affect International Trade? A Country-Level and Industry-level Analysis. Journal of Risk Research 20: 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osberghaus, Daniel. 2019. The Effects of Natural Disasters and Weather Variations on International Trade and Financial Flows: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change 3: 305–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalia, Rosa Bernardini, and Silvia Bertarelli. 2015. Trade Costs in Bilateral Trade Flows: Heterogeneity and Zeroes in Structural Gravity Models. The World Economy 38: 1744–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pástor, Ľuboš, and Pietro Veronesi. 2013. Political uncertainty and risk premia. Journal of Financial Economics 110: 520–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomfret, Richard, and Patricia Sourdin. 2010. Why do trade costs vary? Review of World Economics 146: 709–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugal-Perez, Alberto, and John Wilson. 2009. Why trade facilitation matters to Africa. World Trade Review 8: 379–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raddatz, Claudio. 2007. Are external shocks responsible for the instability of output in low-income countries? Journal of Development Economics 84: 155–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubínová, Stela, and Mehdi Sebti. 2021. The WTO Global Trade Costs Index and Its Determinants. WTO Staff Working Paper, No. ERSD-2021-6. Geneva: World Trade Organization (WTO). [Google Scholar]

- Saijo, Hikaru. 2017. The Uncertainty Multiplier and Business Cycles. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 78: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakyi, Daniel, Isaac Bonuedi, Eric Evans, and Osei Opoku. 2018. Trade facilitation and social welfare in Africa. Journal of African Trade 5: 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savun, Burcu, and Daniel Tirone. 2012. Exogenous Shocks, Foreign Aid, and Civil War. International Organization 66: 363–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, Ben. 2022. Modelling global value chains: From trade costs to policy impacts. The World Economy 45: 2478–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Wonkyu, and Dukgeun Ahn. 2019. Trade Gains from Legal Rulings in the WTO Dispute Settlement System. World Trade Review 18: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourdin, Patricia, and Richard Pomfret. 2012. Measuring International Trade Costs. The World Economy 35: 740–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svaleryd, Helena, and Jonas Vlachos. 2002. Markets for Risk and Openness to Trade: How are they Related? Journal of International Economics 57: 369–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, Bedassa, Bichaka Fayissa, and Elias Shukralla. 2021. Infrastructure, Trade Costs, and Aid for Trade: The Imperatives for African Economies. Journal of African Development 22: 38–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). 2020. Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation for Transport Networks and Nodes. Geneva: UNECE. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nieuwerburgh, Stijn, and Laura Veldkamp. 2006. Learning Asymmetries in Real Business Cycles. Journal of Monetary Economics 53: 753–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijil, Mariana, and Laurent Wagner. 2012. Does Aid for Trade Enhance Export Performance? Investigating on the Infrastructure Channel. World Economy 35: 838–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voon, Tania. 2015. Exploring the Meaning of Trade-Restrictiveness in the WTO. World Trade Review 14: 451–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Laurent. 2014. Identifying thresholds in aid effectiveness. Review of World Economics 150: 619–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2013. World Bank Development Report 2014: Risk and Opportunity. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization. 2012. Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade. In WTO Analytical Index: Guide to WTO Law and Practice (WTO Internal Only). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 633–82. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization. 2021. World Trade Report 2021: Economic Resilience and Trade. Geneva: World Trade Organization. [Google Scholar]

| POLS | FE | Two-Step System GMM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Log(TRCOST) | Log(TRCOST) | Log(TRCOST) | Log(TRCOST) | Log(TRCOST) |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Log(TRCOST)t−1 | 1.196 *** | 0.637 *** | 1.071 *** | 1.049 *** | 1.092 *** |

| (0.0242) | (0.0486) | (0.0321) | (0.0288) | (0.0299) | |

| Log(TRCOST)t−2 | −0.290 *** | −0.0749 *** | −0.233 *** | −0.199 *** | −0.214 *** |

| (0.00964) | (0.0186) | (0.0324) | (0.0263) | (0.0267) | |

| DUR | 0.000347 ** | −0.00333 *** | −0.00265 *** | −0.00161 ** | −0.00231 ** |

| (0.000172) | (0.000552) | (0.000951) | (0.000652) | (0.00101) | |

| Log(EVI) | 0.0160 * | 0.0644 * | 0.0583 *** | ||

| (0.00874) | (0.0353) | (0.0131) | |||

| Log(EXPOSURE) | 0.0314 *** | ||||

| (0.0108) | |||||

| Log(SHOCK) | 0.0267 *** | ||||

| (0.00850) | |||||

| Log(GDPC) | −0.00609 | −0.102 *** | 0.0162 * | −0.00272 | 0.0168 * |

| (0.00411) | (0.0289) | (0.00937) | (0.00629) | (0.00957) | |

| Log(ODA) | −0.00770 *** | 0.00782 *** | 0.00530 | 0.000786 | −0.000482 |

| (0.00144) | (0.00174) | (0.00333) | (0.00326) | (0.00358) | |

| FINDEV | −0.0247 *** | −0.0116 | −0.0474 *** | −0.0599 *** | −0.0541 *** |

| (0.00695) | (0.0146) | (0.0172) | (0.0145) | (0.0158) | |

| INST | 0.000688 | 0.00538 | 0.00126 | 0.00708 ** | 0.00181 |

| (0.00243) | (0.00518) | (0.00388) | (0.00299) | (0.00380) | |

| Log(TERMS) | −0.0160 *** | −0.0195 *** | −0.0447 *** | −0.0246 ** | −0.0396 *** |

| (0.00477) | (0.00608) | (0.0108) | (0.00967) | (0.0104) | |

| Constant | 0.689 *** | 2.975 *** | |||

| (0.159) | (0.216) | ||||

| Observations—Countries | 582–121 | 582–121 | 582–121 | 602–121 | 583–121 |

| R-squared/Within R-squared | 0.878 | 0.417 | |||

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.6661 | 0.9019 | 0.7641 | ||

| OID (p-Value) | 0.2675 | 0.3311 | 0.4418 | ||

| Log(TARIFF) | Log(NTARIFF) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

| One-period lag of the dependent variable | 0.643 *** | 0.997 *** |

| (0.0307) | (0.0189) | |

| Two-period lag of the dependent variable | −0.0641 *** | −0.132 *** |

| (0.0134) | (0.0146) | |

| Three-period lag of the dependent variable | 0.0808 *** | |

| (0.0122) | ||

| DUR | −0.000436 *** | −0.00202 ** |

| (0.000131) | (0.000829) | |

| Log(EVI) | 0.00423 ** | 0.0780 *** |

| (0.00195) | (0.00937) | |

| Log(NONTARIFF) | 0.00949 *** | |

| (0.00289) | ||

| Log(TARIFF) | 0.339 *** | |

| (0.0850) | ||

| Log(GDPC) | 3.05 × 10−05 | 0.00780 |

| (0.00114) | (0.00618) | |

| Log(ODA) | −0.000408 | 5.38 × 10−05 |

| (0.000417) | (0.00261) | |

| FINDEV | 0.00434 ** | −0.0636 *** |

| (0.00200) | (0.0124) | |

| INST | −0.00101 * | −0.00199 |

| (0.000603) | (0.00255) | |

| Log(TERMS) | −0.000650 | −0.0266 *** |

| (0.00171) | (0.00842) | |

| Observations—Countries | 404–107 | 503–115 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0255 | 0.0000 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.8789 | 0.7797 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.3547 | 0.5091 |

| Variables | Log(TRCOST) | Log(TRCOST) | Log(TRCOST) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Log(TRCOST)t−1 | 1.083 *** | 1.062 *** | 1.097 *** |

| (0.0249) | (0.0229) | (0.0234) | |

| Log(TRCOST)t−2 | −0.242 *** | −0.191 *** | −0.221 *** |

| (0.0248) | (0.0196) | (0.0230) | |

| Log(EVI) | 0.0539 *** | ||

| (0.0104) | |||

| DUR | −0.00324 | 0.0139 *** | 0.00344 |

| (0.00494) | (0.00310) | (0.00403) | |

| DUR *Log(EVI) | 0.000147 | ||

| (0.00137) | |||

| DUR *Log(EXPOSURE) | −0.00427 *** | ||

| (0.000911) | |||

| Log(EXPOSURE) | 0.0256 *** | ||

| (0.00884) | |||

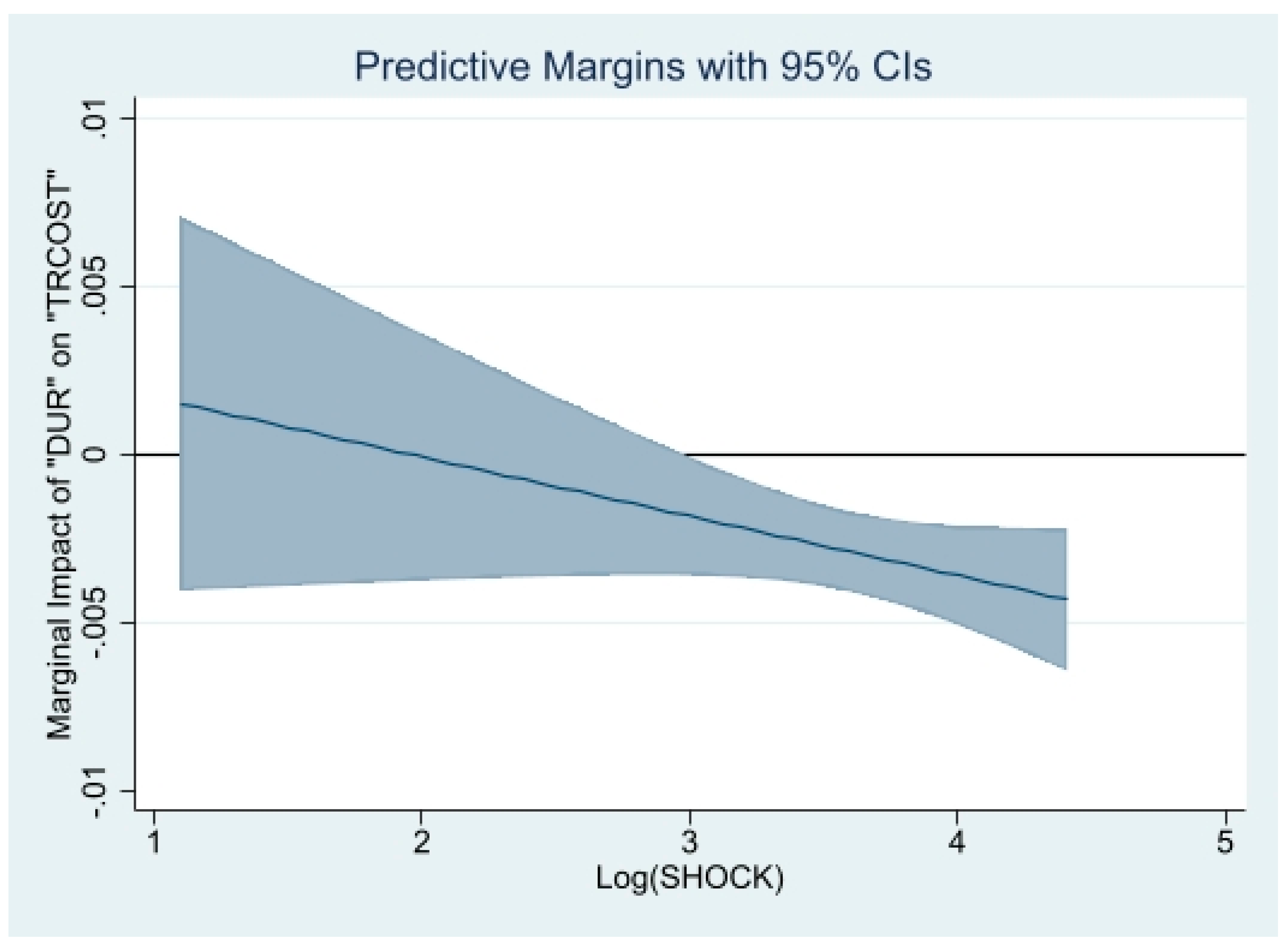

| DUR *Log(SHOCK) | −0.00176 | ||

| (0.00111) | |||

| Log(SHOCK) | 0.0316 *** | ||

| (0.00651) | |||

| Log(GDPC) | 0.0139 * | 0.00147 | 0.0110 |

| (0.00756) | (0.00452) | (0.00764) | |

| Log(ODA) | 0.00619 ** | −0.00212 | 0.000885 |

| (0.00258) | (0.00239) | (0.00281) | |

| FINDEV | −0.0418 *** | −0.0592 *** | −0.0303 ** |

| (0.0132) | (0.0114) | (0.0135) | |

| INST | 0.00351 | 0.00497 * | 0.00189 |

| (0.00315) | (0.00279) | (0.00328) | |

| Log(TERMS) | −0.0439 *** | −0.0238 *** | −0.0457 *** |

| (0.00984) | (0.00787) | (0.0100) | |

| Observations—Countries | 582–121 | 602–121 | 583–121 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.6307 | 0.9263 | 0.7111 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.3120 | 0.4697 | 0.2713 |

| Variables | Log(TRCOST) | Log(TRCOST) | Log(TRCOST) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| One-period lag of the dependent variable | 1.049 *** | 1.091 *** | 1.076 *** |

| (0.0232) | (0.0239) | (0.0267) | |

| Two-period lag of the dependent variable | −0.215 *** | −0.248 *** | −0.212 *** |

| (0.0244) | (0.0267) | (0.0315) | |

| DUR | 0.0191 *** | 0.00909 ** | 0.0406 *** |

| (0.00617) | (0.00371) | (0.00773) | |

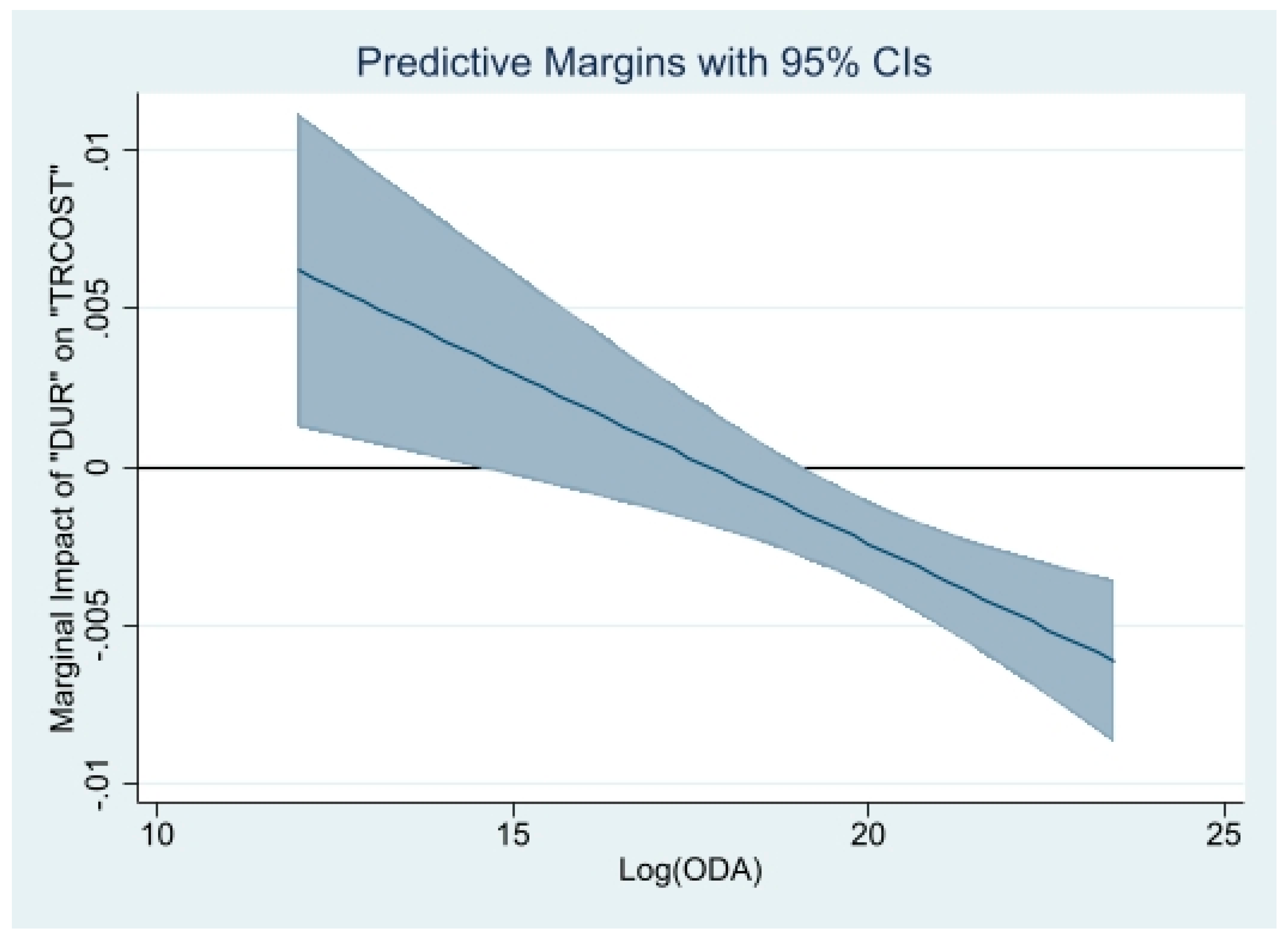

| DUR *Log(ODA) | −0.00108 *** | ||

| (0.000309) | |||

| Log(ODA) | −0.00103 | ||

| (0.00245) | |||

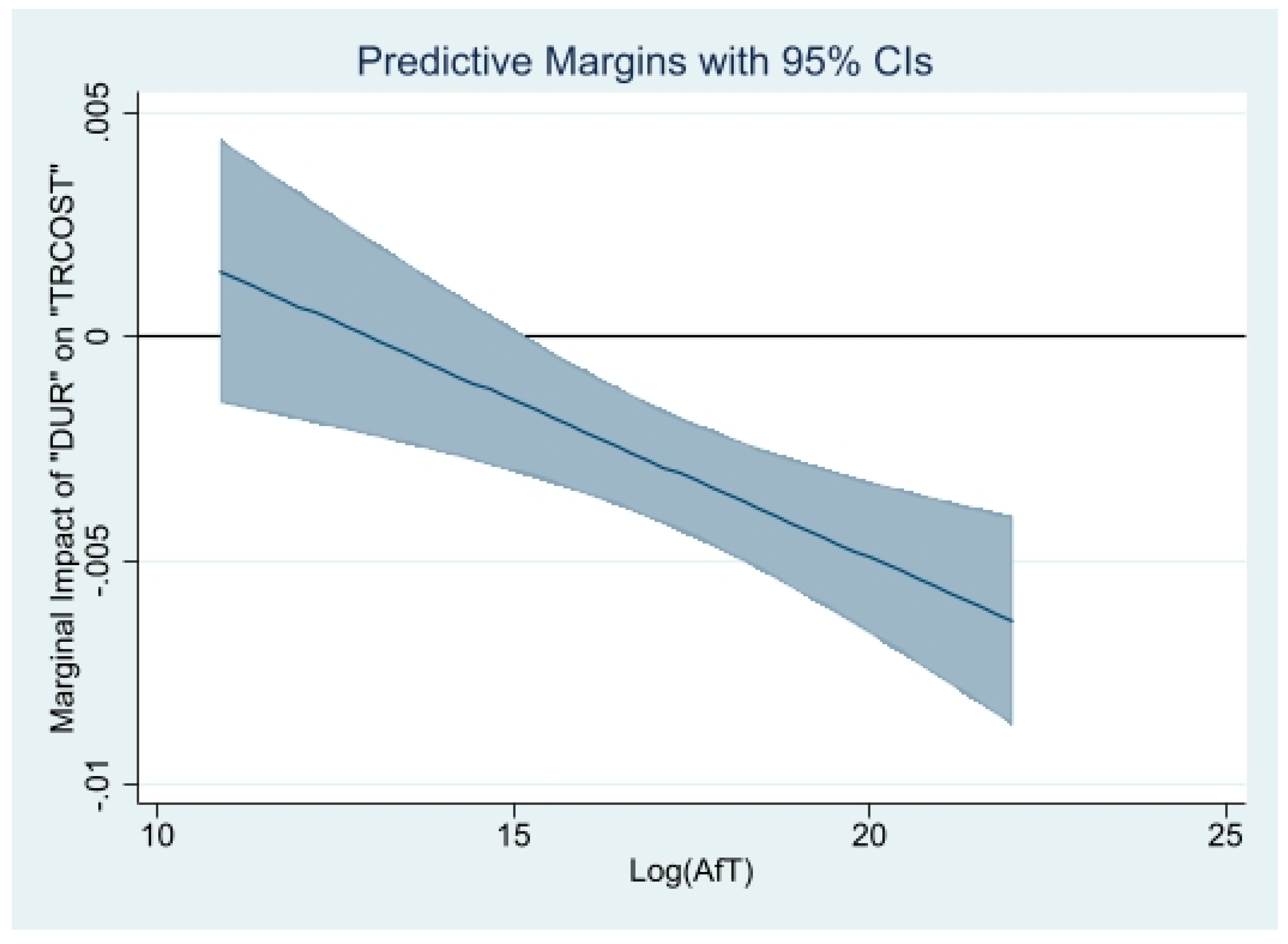

| DUR *Log(AfT) | −0.000701 *** | ||

| (0.000211) | |||

| Log(AfT) | 0.00395 | ||

| (0.00260) | |||

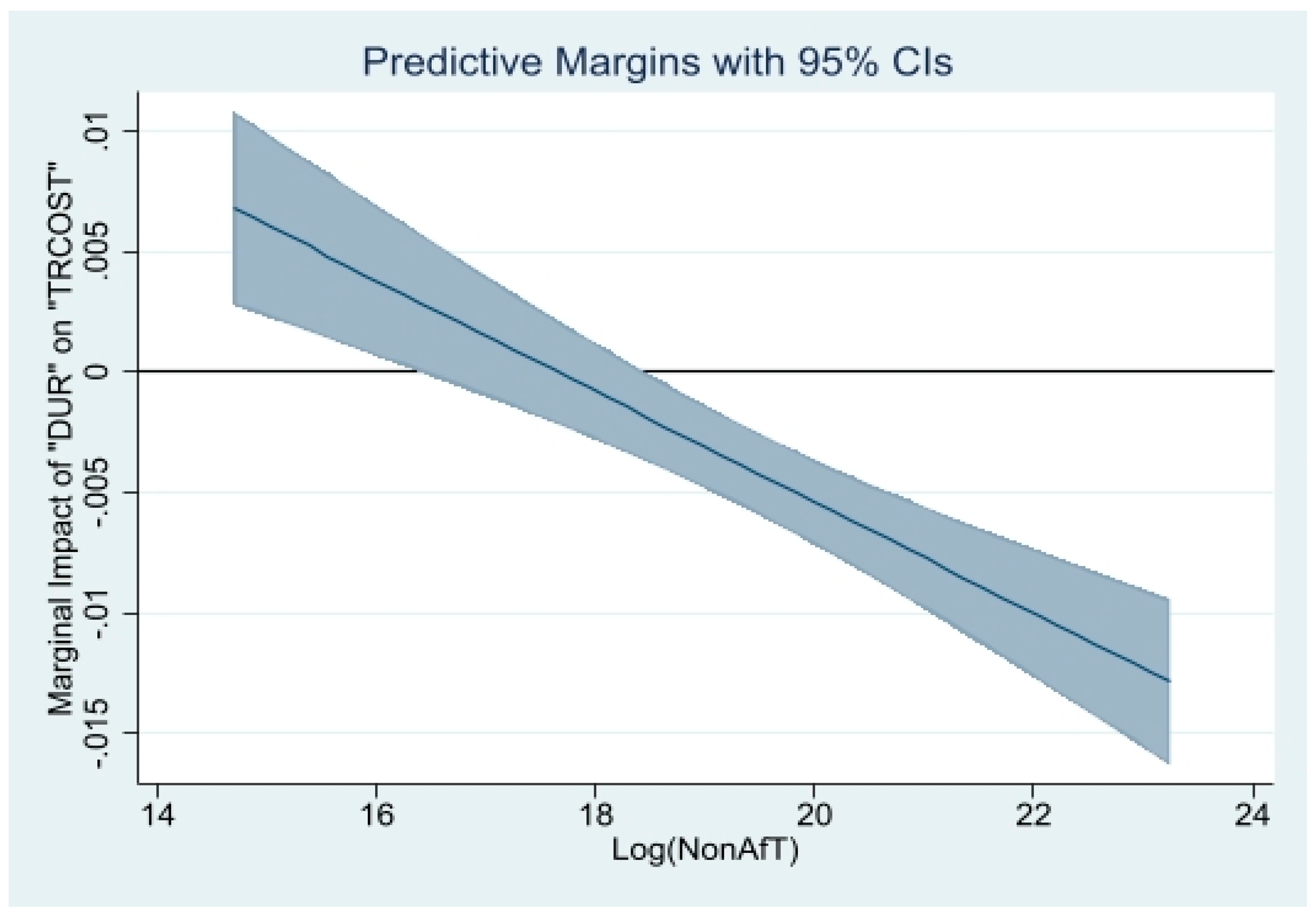

| DUR *Log(NonAfT) | −0.00230 *** | ||

| (0.000397) | |||

| Log(NonAfT) | 0.00676 ** | ||

| (0.00274) | |||

| Log(EVI) | 0.0326 *** | 0.0593 *** | 0.0462 *** |

| (0.0107) | (0.0124) | (0.0124) | |

| Log(GDPC) | 0.00238 | 0.0145 ** | 0.00598 |

| (0.00542) | (0.00629) | (0.00761) | |

| FINDEV | −0.0574 *** | −0.0503 *** | −0.0534 *** |

| (0.0151) | (0.0134) | (0.0144) | |

| INST | 0.00679 *** | −0.000464 | 0.00500 * |

| (0.00235) | (0.00293) | (0.00289) | |

| Log(TERMS) | −0.0407 *** | −0.0334 *** | −0.0379 *** |

| (0.00993) | (0.00969) | (0.0107) | |

| Observations–Countries | 582–121 | 592–116 | 592–116 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.7845 | 0.6873 | 0.8952 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.3012 | 0.2404 | 0.2446 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gnangnon, S.K. Duration of the Membership in the GATT/WTO, Structural Economic Vulnerability and Trade Costs. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2023, 16, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16060282

Gnangnon SK. Duration of the Membership in the GATT/WTO, Structural Economic Vulnerability and Trade Costs. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2023; 16(6):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16060282

Chicago/Turabian StyleGnangnon, Sena Kimm. 2023. "Duration of the Membership in the GATT/WTO, Structural Economic Vulnerability and Trade Costs" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16, no. 6: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16060282

APA StyleGnangnon, S. K. (2023). Duration of the Membership in the GATT/WTO, Structural Economic Vulnerability and Trade Costs. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(6), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16060282