Abstract

The focus of this confirmatory research was on consumer attitudes towards the sustainability of fashion brands and how these attitudes influence their purchasing decisions. The aim was to explore if the gap between attitudes and purchasing behaviour was present within Croatian consumers to the same extent as previous research has shown. A survey was conducted of 263 respondents with purchasing power to examine their perception, awareness of, and attitudes towards sustainability and eco-fashion as consumers. The data collected were analysed using descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. The results suggest that participants have a positive attitude towards the sustainability of fashion brands. Moreover, a positive correlation was found between the importance of fashion brand sustainability and consumers’ decisions to buy sustainable clothing products. However, the sustainability of a fashion brand or product is among the least important factors in their purchasing decision. This could mean that their positive attitude may not necessarily be reflected in actual purchasing behaviour, which is consistent with previous research. The results of this study provide a framework for a greater understanding of the various factors that may influence consumer behaviour, such as the sustainability of a fashion brand or product, potentially facilitating the development of relevant strategies in the fashion industry and changing the way fashion works and is perceived in the future.

1. Introduction

The concept of sustainable fashion emerged in the 1960s, when consumers became aware of the impact of the fashion industry on the environment and wanted to change clothing manufacturing practices (Jung and Jin 2014). Sustainable fashion was negatively perceived at first; however, this changed with anti-fur campaigns in the 1980s and 1990s. More recently the term has been increasingly associated with fair working conditions and a sustainable business model (Joergens 2006), as well as organic and environmentally friendly materials, certifications, and traceability (Henninger 2015). Slow and sustainable fashion focuses on the ethical practices of producers and consumers, reduced production, and associated impacts. Moreover, it prioritises quality over quantity, i.e., production and purchase of quality products over production and purchase of large quantities of products (Fletcher 2010; Ertekin and Atik 2014). The apparel and fashion industry is one of the greatest polluters and contributes to different social and ecological problems (McNeill and Venter 2019). With the turnover in knowledge about environment and ecology, as well as beliefs, opinions, and attitude of consumers, the demand for eco-friendly apparel has grown (Khare and Sadachar 2017). Although there has been a positive shift in awareness about apparel sustainability, green fashion makes up less than 10% of the entire fashion market (Jacobs et al. 2018). Due to the affordability of fast fashion products, the consumers who are aware of sustainable fashion often do not support sustainable consumption with their purchasing decisions and behaviour (McNeill and Moore 2015). Previous research has indicated the paradox between increased acceptance of sustainable fashion and lack of actual purchasing behaviour, known as the attitude –behaviour gap (Wiederhold and Martinez 2018). The paper aims to examine whether consumers research fashion brand sustainability before buying their products, i.e., to determine whether sustainability practices of a fashion brand have an impact on consumer purchasing decision. Furthermore, what motivates buyers when it comes to purchasing apparel and what they seek for in fashion items. Such information can help retailers in sustainable fashion improve their offers and supply chain, as well as provide enlightenment about the issues that cause gaps between attitudes and actions. In addition, the purpose of this paper is to offer a better insight into consumer consumption of sustainable fashion in Croatia, and to provide a framework for further research into this topic.

2. The Impact of Fashion Brand Sustainability on Consumer Decisions to Purchase Their Products

In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development defined sustainable development as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’. Sustainable fashion is often described as an oxymoron (Clark 2008) because fashion as such dictates that something is in or out of fashion, which contradicts the long-term perspective of sustainability (Walker 2006). This also explains consumer scepticism towards sustainable fashion brands, as they perceive sustainable fashion as a contradictory term (Henninger et al. 2016). The fashion industry is facing increasing scrutiny of its supply chain operations that pollute the environment. However, despite widely known environmental impacts, the industry continues to grow, in part due to the growth of fast fashion, which relies on cheap production, frequent consumption and short-term use of clothes (Niinimäki et al. 2020). Sustainable fashion is more than just a fad; it also considers the social, natural, and economic ‘price’ paid in fashion manufacturing, includes a number of aspects, and demands accountability from fashion brands (documentary: The True Cost 2015). The definitions of sustainable fashion in the literature vary; however, they all include the same elements—the impact of the fashion industry on the environment and all stakeholders through different aspects, including society as a whole. It is possible to distinguish eight dimensions making up the sustainable fashion construct (Shen et al. 2013):

- Recycled—Recycled apparel products are made from reclaimed materials from used clothing.

- Organic—Organic products are made from natural sources without any pesticides and toxic elements and/or raw materials.

- Vintage—Refers to any second-hand clothes and up-cycled clothes that have been given a new life.

- Vegan—Products that do not contain leather or animal tissue products.

- Artisan—Products that continue the skills of ancestral traditions.

- Locally made—Includes products that require little transportation and contribute to the local economy.

- Custom made—The goal of this personalised design is to encourage quality and slow fashion design rather than mass-produced disposable fashion.

- Fair Trade certified—Includes products made by companies that show respect for employees and their human rights.

Fast fashion, a dominating manufacturing concept in the fashion industry today, is the antipode of sustainable or slow fashion. Fast fashion chains have a negative impact on the environment because, among other things, many of the clothes manufactured in such business models contain plastic fibres (Barnes and Lea-Greenwood 2006). Moreover, it has been reported that one garbage truck worth of clothes is disposed of or incinerated every second. Washing clothes generates 500,000 tons of microfibers, which then end up in the oceans (Ellen MacArthur Foundation 2017). Based on these data, it can be concluded that the fashion industry is a major contributor to environmental pollution. Moreover, the industry is growing, changing, and responding to trends (both market and fashion), so its impact is expected to grow as well. Therefore, it is important to reduce the negative impacts of manufacturing processes on the environment and society, improve responsible business practices of fashion brands, and increase consumer awareness of the consequences of overconsumption of clothing. In addition to creating negative environmental impacts, the emergence of fast fashion has changed consumer attitudes towards clothing consumption, which is associated with cheap production and procurement of materials from foreign industrial markets. This has created a culture of impulse buying in the fashion industry, where new garments are available to the average consumer every week. It is essential that consumers understand the differences between the consequences of cheap and fast fashion and altruistic interests in environmental sustainability. This is the key to real change in consumer habits and behaviours (McNeill and Moore 2015).

One of the most important factors affecting the environment during the product use phase is the lifespan of a garment. Today, garments are far cheaper compared to household incomes than a few decades ago (Niinimäki 2011). Due to low clothing prices and high household incomes, the consumption of extremely cheap and disposable clothing with a very short lifespan has increased (Jackson and Shaw 2009). Textile and clothing prices have fallen and, currently, consumers own more and more cheap clothes and low-quality textiles (Niinimäki 2011). Low-quality and cheap clothes are easy to discard, so extending the life span of garments is one of the most critical issues for sustainable development (Niinimäki 2015). The life span of garments can be prolonged in a variety of ways, e.g., through resale, donation, rental services or sharing, or engaging with local communities. However, consumers often do not consider these as part of sustainable fashion and sustainable consumer behaviour (KPMG 2019).

2.1. Sustainable Fashion Consumption Behaviour

The field of consumer behaviour covers a wide area. It is the study of the processes involved when individuals or groups select, purchase, use, or dispose of products, services, ideas, or experiences to meet their needs and desires. Consumers take many forms and the items consumed can include anything, while the needs and desires we satisfy range from hunger and thirst to love, status or even spiritual fulfilment. The consumer is generally considered to be an individual who identifies a need or desire, makes a purchase, and then disposes of the product in the consumption process (Solomon et al. 2006). Consumer interest in a particular area or product is called consumer involvement; it can be a permanent involvement—for example when people who are interested in fashion gather information about news in the field, read magazines, and follow the topic on social networks. Such interest is caused by the individual’s internal commitment to a specific area that they follow in the long run and in which they want to become an expert (Kesić 2006). Definitions of ethical consumer are broad, and the term ‘ethical consumption’ is used to refer to a number of belief systems (Shaw and Connolly 2006). Taking into account different views, ethical consumers are individuals who consider the wider impact of their consumption on other people, animals and/or the environment (Barnett et al. 2005). The biggest challenge of sustainable consumption is how to match present wants without depleting upcoming generations and the environment in the long run (Sesini et al. 2020). Despite the shift to sustainable practices in many industries, including fashion, consumers have yet to fully embrace sustainable goods and sustainable business practices in the fashion industry (Brooker 1976; Butler and Francis 1997; Carrigan and Attalla 2001). In addition, studying the desire to consume fast fashion and barriers to embracing sustainable fashion or adopting ethical fashion consumption practices will highlight the differences between attitudes and behaviours among self-proclaimed fashion-conscious consumers. More recently, as sustainability emerges as a ‘megatrend’ (Mittelstaedt et al. 2014), organisations have begun to use words such as ‘eco-friendly’, ‘organic’, ‘environmentally friendly’ and their synonyms in their marketing messages (Chen and Chang 2013). The research that included systematic review and research agendas from 2016 to 2020 has shown that academia increased the research on consumers and sustainability, having peaked in 2019 (Sesini et al. 2020). Although companies benefit from transparency and clear communication about their sustainable practices in the garment manufacturing process, more and more of them are engaging in greenwashing, which is a practice of misleading advertising, often using environmental certifications, eco labels and logos (Delmas and Burbano 2011). A challenge faced by fashion brands is to convincingly explain the benefits of sustainable fashion to consumers, so as to encourage them to make informed purchases (Henninger et al. 2016). Although 50% of European consumers claim to be willing to pay a higher price for sustainable products, the market share of sustainable products is less than 1% (De Pelsmacker et al. 2005). Positive consumer attitudes do not always translate into action, and this is generally known as the attitude–behaviour gap. If money is an issue, consumers can support sustainable fashion by simply not buying anything (Shen et al. 2013). Current literature provides an insight into the gap between consumer attitude and purchase behaviour, implying that a positive attitude towards sustainable fashion is not always followed by an according purchase (Wiederhold and Martinez 2018), although it has been found that environmental attitude has a positive association with intent to purchase sustainable clothes (Nguyen et al. 2019). Experts have also warned that the promotion of sustainable fashion by high street retailers could discourage consumers from buying sustainable products and be misleading, as these brands continue to produce new lines with an average turnover of 60 days—contradictory to sustainable fashion principles. Manufacturers who declare they are a part of sustainable fashion should clearly communicate their offer and highlight what makes their collections sustainable to avoid allegations of greenwashing (Henninger et al. 2016). It also raises suspicion that the fashion industry is based on rapid turnover and consumption of fashion, which is against slow fashion principles (Joy et al. 2012).

Even though there are segments of consumers who are concerned about the social and environmental impact caused by their practices, previous research suggests that providing an opportunity to buy sustainable clothing alone would not bring about the necessary changes in consumers’ clothing purchase, care, and disposal behaviours. Clothing sustainability is a very complex concept and consumers lack sufficient knowledge and understanding of sustainable practices of fashion brands. In addition, consumers are diverse in their concerns. Finally, buying clothes is not an altruistic act, and research shows that sustainability is low on the list of consumer purchase criteria (Harris et al. 2016). To encourage more sustainable clothing consumption behaviour, it is necessary to employ consumer-focused marketing to change consumer behaviour. This involves marketing that shows a good understanding of customer needs, buying behaviour and the issues that influence their purchasing decisions and choices, and takes into account social issues. In addition, sustainable clothing needs to fulfil the core roles that clothing plays and meet consumers’ needs. Most consumers are not willing to sacrifice their fashion needs and desires for the environment. The gap between consumers’ attitudes towards sustainability and green behaviour is significant and creates an unbalanced psychological state. Businesses must choose the most effective approach to communication, i.e., nudge consumers towards sustainable fashion through subtle persuasion tactics, rather than rely on narratives that explicitly tell people to ‘buy green’ (Lee et al. 2020). In addition, it is necessary to reshape consumer behaviour and social norms to protect the environment and the well-being of all stakeholders in the production process. An interdisciplinary approach is needed, which will draw on the experience of experts and previous research (Harris et al. 2016). Action is required from all parties in the fashion industry, from retail stores, designers, managers and, naturally, consumers. Cost pressures and the level of competition in the fashion industry are very high, making it difficult to change business practices. Nevertheless, it is important that the industry as a whole (from fibre production to retail) takes responsibility for its impact on the environment, including the use of water, energy and chemicals, CO2 emissions, and waste generation. Minimising and mitigating these impacts require change, which companies are often opposed to for a number of reasons, primarily economic ones. For instance, the use of cleaner processes will increase production costs, a cost ultimately borne by consumers, which could end cheap fast fashion, leading to an economic decline in the fashion industry (Niinimäki et al. 2020). It is important to mention that both companies and consumers in the textile industry must adopt sustainable practices, as both stakeholders are responsible for making the textile sector the second largest polluter in the world. New technology needs to be developed and business model strategies redefined within the fashion industry, while companies should establish a common method of assessing sector sustainability (Negrete and López 2020). Lately, the concept that has become increasingly popular in terms of sustainability is circular economy (Niinimäki 2017). It is a principle of cycled resources in an economic system, for the purpose of inducing economic and environmental benefits. Experts in the field agree that circular economy encourages sustainable consumption (Tunn et al. 2018). It has gained attention as it has the possibility to take on problems of overconsumption and pre-term disposal. The correct circular business model can support a company in achieving economic, as well as environmental, sustainability (Murray et al. 2017).

2.2. Previous Research on Consumers’ Sustainable Apparel Consumption Behaviour

Sustainable fashion is mainly associated with sustainable practices, such as the use of renewable and environmentally friendly raw materials, carbon emission reduction, durability, and longevity of products (Joergens 2006; Shen et al. 2013). Research shows that consumers also associate sustainable fashion with social aspects, such as working conditions, wage equality, workplace safety, and labour rights (McNeill and Moore 2015). The following should also be considered part of ethical and sustainable use and consumption: decreasing clothing purchases, planning purchasing and fostering product attachment, buying durable clothing of classic style and high quality, buying eco-friendly materials and labels, increased use of clothing products, less frequent washing, as well as care and mending to extend their lifetime, etc. (Niinimäki 2013). European countries have international leadership when it comes to sustainable consumption and sustainable practices in production (Wang et al. 2018). The research findings have shown that academic papers covering the trends of consumer sustainable behaviour in recent years were predominantly performed in Europe (55% of analysed papers), specifically in Italy (14% of studies), with clothing sustainability topics at third place in the most popular ones (8% of papers) (Sesini et al. 2020). On the other note, an earlier UK study found that consumers have not worn almost half of their wardrobes in the last twelve months. It is estimated that this amounts to 2.4 billion unused garments in the UK alone (Belz and Peattie 2011). Moreover, it was reported that more than half of fast fashion produced is disposed of in under a year (Ellen MacArthur Foundation 2017).

Self-expression through clothing is important to many consumers, and thus their motivation to be trendy often prevails over their motivation for ethical or sustainable fashion purchases. This is apparent in the conflict of desire for consumption with efforts to limit it. This internal conflict occurs due to insufficient knowledge about the negative effects of disposing of clothing on the environment (Birtwistle and Moore 2007). Furthermore, the gap between consumer beliefs and behaviour is the result of other factors that have a higher impact on their purchasing behaviour (Carrigan and Attalla 2001). These factors include price, value, trends, and fashion brand image—elements that are particularly important in fashion consumption (Solomon and Rabolt 2004). Even when consumers are willing to buy ethically produced garments or garments made from sustainable fabrics, the desire for new and trendy clothes increases the volume of clothes disposed of in landfill sites because they are considered out of fashion after limited use (Morgan and Birtwistle 2009). Research into the link between attitudes and behaviour suggests there is a significant relationship between the perception of fashion serving a function vs. being a status symbol, peer influence, and the level of consumer familiarity with fashion products. Fast fashion is the manufacturers’ response to consumer demand for newness (Barnes and Lea-Greenwood 2006). Consumers who use fashion as a means of self-expression are unlikely to be interested in the sustainable fashion market, as their fashion priorities are linked to other values (McNeill and Moore 2015). Individuals who consume fast fashion the most are least interested in environmental issues and show little concern for both environmental and social issues (Birtwistle and Moore 2007). In addition, low prices and the possibility to change their clothing and style often will be a priority for such consumers. Even the consumers who view clothing as a functional necessity will often, due to peer pressure, buy clothing products ‘for the sake of fashion’ rather than their function. However, some consumers have shown growing environmental and social welfare concerns and are developing positive attitudes towards sustainable fashion products. Such consumers show certain positive consumption behaviours, but there are still barriers to the consumption of sustainable fashion. Most of these consumers have developed social awareness and are concerned about the social norms and behaviour of their peers, which may encourage them to purchase sustainable clothing. Therefore, the largest potential to increase the share of sustainable fashion market lies in this consumer group. Garments designed to combine ethical sustainable production with the positive aspects of fast fashion may go a long way towards overcoming barriers to sustainable fashion consumption, including the lack of social support for purchasing sustainable fashion products, lack of awareness, and perception that the prices are high. Due to the large number of such consumers and their high concern for social norms, mass media and social networks could be a valuable tool in creating awareness among them. Often such individuals are more concerned about how they are perceived by their peers than about the price of the product. In addition, they are often willing to pay a lot of money for a piece of clothing they crave. Consumers who show great concern for the environment and social issues, i.e., ethics and social welfare have a negative attitude towards fast fashion. However, even such consumers experience a conflict between the desire to be fashionable and the desire to reduce overall consumption. One of the negative aspects of the described consumer behaviour for manufacturers of sustainable fashion products is that such consumers prioritise overall reduction in consumption over fashion desires, and the culture of impulse buying has little impact on them. It is possible to influence the overall consumption of this particular consumer group, as they already buy sustainable fashion products (McNeill and Moore 2015).

Furthermore, previous research on consumer behaviour shows that respondents associate sustainable fashion with procurement and production processes, while seemingly ignoring social aspects, such as fair wages and working conditions. Consumers have also reported that due to the use of more environmentally friendly materials, sustainable fashion has a significantly higher price than conventional (fast) fashion. The price of sustainable clothing is often seen as an obstacle to sustainable consumption because consumers, even if they are willing to buy such clothing, may not be able to afford it. In addition, consumers report that factors, such as style, trend, and availability, also play a role in purchasing sustainable fashion products (McNeill and Moore 2015).

The results of previous research also show that the participants’ positive attitude towards sustainability does not necessarily reflect on their behaviour. However, an examination of the relationship between consumer attitudes and behaviours has shown that participants with positive attitudes towards environmental sustainability practices are more likely to follow through when purchasing fashion products (Ceylan 2019). Furthermore, research has shown that there is an awareness of and concern for environmental protection issues. Still, the level of concern about environmental impacts of the fashion industry among consumers is not sufficiently high to reflect in sustainable purchasing of apparel, footwear, and accessories (KPMG 2019), and sustainability is among the least important consumer purchase criteria (Harris et al. 2016). Research shows that consumers are aware and supportive of ecological fashion approaches, but do not act accordingly. As for the relationship between knowledge, attitudes and behaviours, research has shown that increasing the level of knowledge about sustainable fashion has a slightly positive effect on the respondents’ attitudes and behaviour towards ecological fashion practices (Ceylan 2019). Consumers are more aware of the association of products made of recycled materials, second-hand materials and natural fibres, and companies that follow sound environmental and social practices with the concept of sustainability. The respondents were least aware of the association between sustainable fashion and products made of leather materials (Shen et al. 2013). Furthermore, research suggests that, despite the concern for the environment, the vast majority of consumers are not willing to pay a higher price for sustainable fashion brand products and would prefer if sustainable fashion cost the same as conventional fast fashion (KPMG 2019). Ultimately, the long-term stability of the fashion industry depends on the complete abandonment of the fast fashion model, which will lead to a decline in overproduction and overconsumption and a corresponding reduction in material throughput. Such transformations require international coordination and involve changing the mind-set at both the business and consumer levels (Niinimäki et al. 2020).

3. Methodology

An online questionnaire created on the Google Forms platform was used to conduct quantitative research. The research was carried out in January of 2021. The respondents were recruited via virtual snowball sampling through e-mail, social networks, and personal contacts, as the questionnaire was not publicly available nor marketed. The researchers sent the questionnaire to their acquaintances, who were also asked to spread to other possible respondents of age. The aimed respondents were Croatians with purchasing power, meaning working-age Croatians, as the research investigates purchasing behaviour. Since there is no standardised questionnaire concerning the impact of sustainable fashion on consumer garment purchase decision, the questionnaire used in this study was prepared based on previous research conducted by Shen et al. (2013) and Ceylan (2019). The questionnaire comprises 15 questions. The first part includes six questions aimed at determining the socio-demographic profile of the respondents. The remaining nine closed-ended questions inquire about their behaviour and attitudes towards certain aspects of sustainable fashion. Depending on the question, the respondents could answer on a 5-point Likert scale, a self-rating scale, or by selecting a statement that best describes their attitude. The five-point Likert scale was chosen because it is the most common tool for measuring respondents’ attitudes, and because the respondents were familiar with it. A total of 263 people, 176 women and 87 men, participated in the survey on a voluntary basis.

Numerous studies have shown that positive attitudes towards sustainable fashion often do not translate into actual behaviour (Chen and Chang 2012; Shen et al. 2013; Ceylan 2019). Whilst consumers have acknowledged the significance of environmentalism and sustainability, their purchase decisions are not associated with ethical consciousness (Han et al. 2017). More specifically, some studies have shown that a high percentage of consumers, more than 80%, search for information about a product on the Internet before buying it (GE Capital Retail Bank 2013). However, sustainability is not a high priority among consumer purchase criteria (Harris et al. 2016). The reason for it might be that the consumers perceive green fashion as more expensive with less satisfactory design and quality of the garment, meaning that sustainable garments suffer in lower performance and high price point (Newman et al. 2014). There are findings that sustainability itself cannot guarantee the success of fashion products, because when consumers are made to decide between a product’s attributes and its greenness, they will not sacrifice their wants just for the sake of being green (Chen and Chang 2012). On the other side of the spectrum, the literature on sustainable fashion shows that sustainability has positive effect on purchasing intentions (Steinhart et al. 2013). Consumers who have concerns about problems connected to sustainability and planet protection show that they can have effect on their decisions, among other factors, when buying fashion products that are green or sustainable (Lundblad and Davies 2016). Moreover, sustainability of products can positively impact purchase intention, especially when a fashion item is made out of recycled materials (Grazzini et al. 2020). Since the literature on the one side shows a very high percentage of consumers who inform themselves before buying—8 out of 10 buyers (GE Capital Retail Bank 2013)—but on the other the sustainability is one of the last influential factors in their buying process, the authors constructed the following hypothesis, drawing on the findings of previous research and relevant literature:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Less than 20% of respondents search for information about a fashion brand and its sustainability policy before buying its products.

Consumer behaviour is different depending on the continent, culture, and country. Environmental concerns among European and American consumers are connected to environmentally friendly decisions, but not among Asian consumers who give more significance to health-related benefits (Eom et al. 2016). To date, no research on the relationship between sustainable fashion practices and consumer behaviour has been conducted in Croatia. Thus, this paper aims to fill this gap by examining the impact of some aspects of sustainable fashion brand practices on the decision of Croatian consumers to buy their clothing, and to determine whether they research a particular brand to see if it is sustainable before buying its products. Although the previously mentioned studies on the world scale have shown contradictory results: firstly, the gap between consumer attitudes and behaviour and secondly a positive sustainability-purchase decision connection, bearing in mind that the topic of sustainable consumption is gaining in popularity in Europe, as well as some researchers have achieved the results that sustainable factors positively affect consumers purchase intentions, the second hypothesis was set, in accordance to previous findings about environmentally conscious decisions:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

There is a strong relationship between the importance of sustainability of fashion brands and the decision to purchase their products.

The target group of this research were working-age adults living in Croatia.

4. Results

The first part of the questionnaire inquired about the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. The distribution of respondents across the 18–26 and the 27–35 age categories is similar (31.2% and 28.5%, respectively). Age distribution across other categories is as follows: 20.5% of respondents are in the age group 36–44, only 8.7% are aged 45–53 years, 7.2% are between the ages of 54 and 62, and finally 3.8% of respondents are above 63 years of age. Data on the level of education are as follows: most respondents have completed graduate studies (44.9%), followed by those who have completed undergraduate studies (24.7%) and secondary school (23.6%). The share of respondents holding a degree of Master of Science is smaller (4.2%), followed by persons with completed postgraduate specialist studies (1.5%), a PhD degree (0.8%) and primary school education (0.4%). The majority of respondents are employed (69.6%), one fifth are students (20.5%), and a small number are unemployed (5.3%), retired (4.2%) or undergoing vocational training (0.4%). Furthermore, most respondents have a monthly income of up to HRK 5500 (40.3%) or between HRK 5501 and 9000 (37.3%). The share of respondents with a monthly income of HRK 9001 to 12,500 (12.2%) is lower, followed by those with incomes ranging from HRK 12,501 to 16,000 (4.9%). The share of respondents with incomes ranging from HRK 16,001 to 19,500 (1.5%) is lowest, whereas the share of those whose income is above HRK 1901 is 3.8%. Finally, three quarters of respondents spend up to HRK 500 per month on garments (74.5%). In terms of monthly spending on garments, the rest of the respondents are distributed as follows: HRK 501 to 1000 (18.6%), HRK 1001 to 1500 (4.2%), HRK 1501 to 2000 (2.3%) and more than HRK 2001 (0.4%).

In the next section of the questionnaire, the respondents were asked to indicate, on a five-point Likert scale, the degree to which they agree or disagree with five statements describing their apparel purchase behaviour. The statements read as follows:

- -

- The sustainability of fashion brands is not a factor in my decision to buy their clothing.

- -

- Before buying an item of clothing, I search for information about the fashion brand’s sustainability policies, practices, and reputation but this is not a key factor in my decision.

- -

- Fashion brands’ sustainability policies have an impact on my decision to buy their clothing.

- -

- Sustainability is a marketing gimmick and, in my opinion, it is not truly a part of the fashion brand’s strategy.

- -

- I prefer to buy clothing from fashion brands that have a sustainable clothing line.

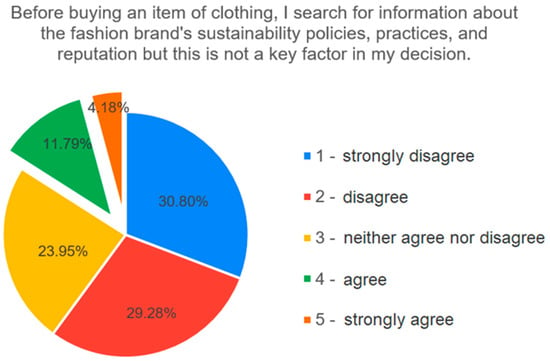

The second statement was used to test the H1 hypothesis. Figure 1 shows the respondents’ agreement with the statements on the five-point Likert scale: 1—strongly disagree, 2—disagree, 3—neither agree nor disagree, 4—agree, 5—strongly agree. Answers of 4 (agree) and 5 (strongly agree) were considered positive. The results show that less than 20% of the respondents agree or strongly agree with the second statement: ‘Before buying an item of clothing, I search for information about the fashion brand’s sustainability policies, practices, and reputation but this is not a key factor in my decision’. To be exact, 15.97% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. In other words, 31 respondents agreed and only 11 strongly agreed with this statement. This confirms hypothesis H1—meaning H1 was accepted, as less than 20% of the respondents search information about the fashion brand’s sustainability policy before buying its products.

Figure 1.

Distribution of respondents’ agreement with the second item. Source: authors’ work.

Furthermore, an analysis was carried out on the correlation between the statements of the variable ‘decision to purchase clothing’ with the items of the variable ‘importance of clothing brand sustainability’. As can be seen from Table 1, there is a relatively small statistically significant positive correlation between the items of the variable ‘decision to purchase a clothing item’ and the items of the variable ‘importance of clothing brand sustainability’. A negligible statistically significant negative correlation exists between the statement ‘The sustainability of fashion brands is not a factor in my decision to buy their clothing’ and items of the variable ‘importance of sustainability of the fashion brand’ relating to the use of biodegradable materials and environmentally friendly dyes in production, reduced water consumption in production, traceability, environmental advice and a clearly labelled sustainable clothing line. Given that the statement about sustainability is negative, i.e., says that brand sustainability is not a factor in the decision to buy clothing of that brand, the obtained values indicate that the respondents who agree with this statement do not find these aspects of sustainable fashion important. This is to say that the mentioned aspects will not correlate with each other. Thus, it may be concluded that there is a significant positive correlation between the items of the variables ‘decision to purchase a clothing item’ and ‘the importance of brand sustainability’, confirming the H2 hypothesis which was accepted. This indicates that the more important the sustainability of a fashion brand is to a person, the more likely it is that they will decide to buy its sustainable products.

Table 1.

Correlation between the items of the variables ‘decision to purchase clothing’ and ‘the importance of brand sustainability’.

To gain a better insight into possible ways of improving advertising and marketing methods, the respondents were asked to rank six factors of sustainable fashion in order of their importance, from the most important to the least important, based on their personal preferences. Table 2 shows the overall ranking of individual factors of sustainable fashion. The factor ‘fair wages and respect for human rights’ were ranked first by most respondents, followed by ‘use of environmentally friendly resources’. The second place was most often taken by the factor ‘adequate use of resources in production (focus on water and chemical use, monitoring of GHG emissions, in particular CO2 emissions, etc.)’. ‘Traceability’ was ranked fifth and sixth as the least important factor. The second least important factor was ‘Animal welfare and/or non-use of materials of animal origin (leather, fur, bones, etc.)’. In conclusion, the social factor of sustainable fashion, i.e., respect and fair treatment of employees was found to be the most important aspect of the sustainability of fashion brands. The data also suggest that the respondents are more concerned about the environmental aspect of sustainable fashion and the use of resources in the fashion industry, while the welfare of animals, which are part of that environment, is of very little importance to them.

Table 2.

Overall ranking of individual factors of sustainable fashion based on importance to the respondents.

Next, the respondents were asked to rank, in terms of importance, seven factors they consider when buying a clothing item based on their personal preference. Table 3 shows the overall ranking of individual factors in order of importance to the respondents. The most important factor for the respondents is ‘the quality and longevity of clothing’, which was ranked first by most respondents. It is followed by ‘the price of clothing’, which was ranked first or second by most respondents. Ranked at the bottom, there is ‘fashion brand (I prefer one brand over others)’ as the least important factor considered when buying a clothing item. The second least important factor is ‘the sustainability of a particular product (e.g., H&M’s Conscious line, C&A’s WearTheChange line and the like)’. ‘Fashion brand sustainability policy’ ranked sixth. This suggests that the sustainability of fashion brands, i.e., the sustainability of clothing products is not a key criterion in deciding to buy a garment made by that brand; in other words, it does not have an impact on consumers’ purchasing decision.

Table 3.

Overall ranking of factors considered in deciding to buy a clothing item in order of importance to consumers.

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to determine the reliability of the questionnaire. The obtained value of 0.695 is acceptable, showing a tendency towards a very good value. It suggests that almost 7 out of 10 respondents agree about the importance of fashion brands’ sustainability. It is of note that the results may be different with a larger number of respondents—this has yet to be determined by future research. The limitations of this research include the smaller sample size, gender, and age distribution, as well as distribution in terms of education level, income, and money spent on clothing. In addition, individuals may be hesitant to share their attitudes towards issues of sustainability and ethical behaviour, despite knowing that the survey is anonymous. The questionnaire was administered online, which means that the conditions could not be controlled, so the reliability of the results may be difficult to determine. In addition, this research, as is the case with the majority of marketing research in general, was conducted over a specific period of time. Nevertheless, the described limitations do not diminish its contribution to the ongoing discussion about this research topic.

5. Discussion

The previously conducted research shows that although a large number of consumers are aware of the importance of environmental issues and support the philosophy of sustainability, there is a gap between ethical awareness and actual decisions and behaviours when purchasing clothing products (Chen and Chang 2012; Shen et al. 2013; Han et al. 2017; Ceylan 2019). The aim of this research was to determine what percentage of consumers search information about the sustainability of fashion brands before buying their products. The results show that this percentage is relatively low, corroborating with the H1, thus confirming the findings of a number of previous studies indicating that consumers’ attitudes towards the sustainability of fashion brands do not translate into actual actions. Even though consumers inform themselves on the products and collect the information before purchase (GE Capital Retail Bank 2013), they do not explore the sustainable side of it. This research also shows that albeit consumers’ awareness of sustainability concerns and the impact of the fashion industry on the environment, their actions do not reflect this as it was found that sustainability was among the least important factors in their purchasing decision. Quality, longevity, and price are the main factors that impact their decision. On the other hand, opposite findings in previous research were also present: sustainability features of products can have positive effect on purchasing intentions (Steinhart et al. 2013), as consumers who are concerned about the environment’s well-being have more tendency to lean towards greener fashion garments (Lundblad and Davies 2016), especially if they are made out recycled materials (Grazzini et al. 2020). Moreover, European consumers that show concern about the environment have a higher chance of making environmentally beneficial decisions (Eom et al. 2016). Additionally, European researchers have shown greater interest in sustainability topics (Wang et al. 2018; Sesini et al. 2020). This is confirmed by H2, which signifies that if consumers give more importance to sustainability, the more likely it is that they will decide to buy sustainable fashion products. To improve the health of the planet, the fashion industry must become more sustainable, and fashion consumers can be the drivers of this change. The results of previous research suggest that sustainable fashion campaigns explain why we need to change, instead of what sustainability is. Sustainability campaigns should aim to raise public awareness of the immediate environmental threats facing all species, including humans. Conscious consumers could thus create a currently non-existent link between environmental protection and green consumption. The gap between consumer attitudes and behaviour will not narrow unless consumers take real action to address the source of the problem. Thus, campaigns promoting sustainability can bring about real behavioural changes by changing the role of fashion in environmental degradation (Lee et al. 2020). Although companies in the fashion industry generally do not maintain sustainable practices, consumers also engage in unsustainable fashion consumption practices. Communication is important for cultivating collaboration between industry stakeholders and creating conscious consumers who adopt sustainable product consumption behaviour. The industry will not be able to achieve sustainability unless all stakeholders adopt sustainable practices in their businesses, the production and supply chain. The assessment of sustainable performance of enterprises in the industry also needs to be improved, which could allow the identification of aspects of business that need to be improved, as well as practices that need to be upgraded or added to the business model (Negrete and López 2020). This study helps to clear the sustainability paradox, the inconsistency between positive attitude when it comes to sustainable factors and purchase decisions. It shows the connection between environmentalism and sustainable fashion. In that sense, sustainability can have an important role in fashion as a whole, as well as sustainable fashion products if more consumers are taught about the destructive side of the industry on nature and our planet. Brands should educate consumers about the environmental problems to make a shift in their knowledge and potentially attitudes which could then lead to bettering their purchase behaviour.

6. Conclusions

The results of the present study are consistent with results from previous research in that they indicate that consumers in general make their purchasing decisions without giving much thought to the impact of their decisions on the environment. Concern for the environment as a factor in consumer decision-making is given low priority, as evident from the answers of the respondents in this survey. In the fashion market, greater importance is placed on factors such as price, value, size, quality, style, convenience of purchase, materials, and many others, while environmental factors are important to a very small percentage of consumers (KPMG 2019). Furthermore, it can be concluded that consumer sustainable product consumption behaviour is often not aligned with positive attitudes towards sustainable fashion. Thus, fashion brands need to identify other consumer priorities (e.g., quality, durability, price etc.) and adjust their advertising approach to address these needs. It is clear that the fashion industry, mainly due to the rise of fast fashion brands, poses a threat to the environment and increases the risk of worker exploitation. When consumers look at their favourite piece of clothing, they probably do not think about the amount of water used to produce it, the chemicals used in the manufacturing process, who made it or where it was made. However, the interest in sustainable fashion and the adoption of sustainable practices (such as reduction in purchases) is growing due to the current coronavirus pandemic, which has brought some fresh hope. The same trend is likely to emerge in Croatia. Research results suggest that consumer behaviour trends in Croatia are similar to those in the rest of the world—consumers have a positive attitude towards sustainable policies and a desire for sustainable consumption, but other factors often prevail in their buying decisions (such as price of the item and its longevity) and their attitudes and desires do not translate into actions. Those consumers who care about the environment show greater interest in purchasing green products. Sustainable product characteristics can have positive impact on the buying intentions. Recent increases in interest about sustainability themes sparks hope that changes might happen in consumers’ consciousnesses. The aim of this research was to determine what percentage of consumers search information about fashion brand sustainability before buying their products. The results show that this percentage is relatively low, which is consistent with the results of a number of previous studies indicating that consumers’ sustainable fashion brand consumption does not reflect their attitudes. Slow fashion is the future. However, a new way of seeing and understanding is needed for the whole system to adopt a sustainable business model, which requires creativity and collaboration between designers and manufacturers, various stakeholders, and end consumers. Systemic changes are needed to make the transition to a better sustainable kind of balance in the fashion industry. One of the most difficult challenges in the future will be to change consumer behaviour and redefine fashion (Niinimäki et al. 2020). The results of this study can provide additional clearance of the topic that is still quite unexplored, as environment connected subjects gained popularity only recently. Further research is necessary on ways of stimulation of sustainable behaviour. In particular, marketers should explore how marketing variables (brand and its reputation, price, design etc.) can be combined with green marketing to reduce sustainability gaps and greatly influence consumer behaviour in order to move towards a sustainable future. In summary, to increase the adoption of sustainable practices and market share of sustainable fashion, it is necessary to raise consumer awareness of sustainable consumption and change their consumption behaviour.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M. and A.H.; methodology, D.M.; software, D.M.; formal analysis, D.M., A.H., and D.V.; investigation, D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M., A.H., and D.V.; writing—review and editing, A.H. and D.V.; supervision, D.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University North (UNIN-DRUŠ-21-1-2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are shown in article and supporting data wasn’t created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barnes, Liz, and Gaynor Lea-Greenwood. 2006. Fast fashioning the supply chain: Shaping the research agenda. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 10: 259–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, Clive, Paul Cloke, Nick Clarke, and Alice Malpass. 2005. Consuming Ethics: Articulating the Subjects and Spaces of Ethical Consumption. Antipode 37: 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belz, Frank-Martin, and Ken Peattie. 2011. Sustainability Marketing: A Global Perspective, 3rd ed. West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Birtwistle, Grete, and Christopher M. Moore. 2007. Fashion clothing—Where does it all end up? International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management 35: 210–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, George. 1976. The self-actualizing socially conscious consumer. Journal of Consumer Research 3: 107–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Sara M., and Sally Francis. 1997. The Effects of Environmental Attitudes on Apparel Purchasing Behavior. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 15: 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, Marylyn, and Ahmad Attalla. 2001. The myth of the ethical consumer—Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? Journal of Consumer Marketing 18: 560–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ceylan, Özgür. 2019. Knowledge, attitudes and behavior of consumers towards sustainability and ecological fashion. Textile and Leather Review 2: 154–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Yu-Shan, and Ching-Hsun Chang. 2012. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Management Decision 50: 502–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yu-Shan, and Ching-Hsun Chang. 2013. Greenwash and Green Trust: The Mediation Effects of Green Consumer Confusion and Green Perceived Risk. Journal of Business Ethics 114: 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Hazel. 2008. SLOW + FASHION—An Oxymoron—Or a Promise for the Future …? Fashion Theory The Journal of Dress, Body and Culture 12: 427–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, Patrick, Wim Janssens, Ellen Sterckx, and Caroline Mielants. 2005. Consumer Preferences for the Marketing of Ethically Labelled Coffee. International Marketing Review 22: 512–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, Magali A., and Vanessa Cuerel Burbano. 2011. The Drivers of Greenwashing. California Management Review 54: 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2017. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. Available online: http://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Eom, Kimin, Heejung S. Kim, David K. Sherman, and Keiko Ishii. 2016. Cultural Variability in the Link Between Environmental Concern and Support for Environmental Action. Psychological Science 27: 1331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertekin, Zeynep Ozdamar, and Deniz Atik. 2014. Sustainable markets: Motivating factors, barriers, and remedies for mobilization of slow fashion. Journal of Macromarketing 35: 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Kate. 2010. Slow fashion: An Invitation for Systems Change. The Journal of Design, Creative Process and the Fashion Industry 2: 259–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GE Capital Retail Bank’s Second Annual Shopper Study Outlines Digital Path to Major Purchases—81% Research Online Before Visiting Store. 2013. Available online: https://www.ge.com/news/press-releases/ge-capital-retailbanks-second-annual-shopper-study-outlines-digital-path-major (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Grazzini, Laura, Diletta Acuti, and Gaetano Aiello. 2020. Solving the puzzle of sustainable fashion consumption: The role of consumers’ implicit attitudes and perceived warmth. Journal of Cleaner Production 287: 125579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Jinghe, Yuri Seo, and Eunju Ko. 2017. Staging luxury experiences for understanding sustainable fashion consumption: A balance theory application. Journal of Business Research 74: 162–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Fiona, Helen Roby, and Sally Dibb. 2016. Sustainable clothing: Challenges, barriers and interventions for encouraging more sustainable consumer behaviour. International Journal of Consumer Studies 40: 309–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, Claudia E., Panayiota J. Alevizou, and Caroline J. Oates. 2016. What is sustainable fashion? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 20: 400–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, Claudia E. 2015. Traceability the new eco-label in the slow-fashion industry?—Consumer perceptions and micro-organisations responses. Sustainability 7: 6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, Tim, and David Shaw. 2009. Mastering Fashion Marketing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Kathleen, Lars Petersen, Jacob Hörisch, and Dirk Battenfeld. 2018. Green thinking but thoughtless buying? An empirical extension of the value-attitude-behaviour hierarchy in sustainable clothing. Journal of Cleaner Production 203: 1155–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergens, Catrin. 2006. Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 10: 360–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joy, Annamma, John F. Sherry Jr, Alladi Venkatesh, Jeff Wang, and Ricky Chan. 2012. Fast fashion, sustainability, and the ethical appeal of luxury brands. Fashion Theory 16: 273–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Sojin, and Byoungho Jin. 2014. A theoretical investigation of slow fashion: Sustainable future of the apparel industry. International Journal of Consumer Studies 38: 510–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesić, Tanja. 2006. Ponašanje potrošača, 2nd Revised Edition. Zagreb: Opinio, pp. 147–48. [Google Scholar]

- Khare, Arpita, and Amrut Sadachar. 2017. Green apparel buying behaviour: A study on Indian youth. International Journal of Consumer Studies 41: 558–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. 2019. Sustainable Fashion—A Survey on Global Perspectives. Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/cn/pdf/en/2019/01/sustainable-fashion.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Lee, Eun-Ju, Hanah Choi, Jinghe Han, Dong Hyun Kim, Eunju Ko, and Kyung Hoon Kim. 2020. How to “Nudge” your consumers toward sustainable fashion consumption: An fMRI investigation. Journal of Business Research 117: 642–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundblad, Louise, and Iain A. Davies. 2016. The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 15: 149–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, Lisa, and Rebecca Moore. 2015. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: Fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. International Journal of Consumer Studies 39: 212–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, Lisa, and Brittany Venter. 2019. Identity, self-concept and young women’s engagement with collaborative, sustainable fashion consumption models. International Journal of Consumer Studies 43: 368–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstaedt, John D., Clifford J. Schultz II, William E. Kilbourne, and Mark Peterson. 2014. Sustainability as megatrend: Two schools of macromarketing thought. Journal of Macromarketing 34: 253–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Louise R., and Grete Birtwistle. 2009. An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits. International Journal of Consumer Studies 33: 190–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Alan, Keith Skene, and Kathryn Haynes. 2017. The Circular Economy: An interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and its application in a global context. Journal of Business Ethics 140: 369–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Negrete, Juan, and Valentina López. 2020. A Sustainability Overview of the Supply Chain Management in Textile Industry. International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance 11: 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, George E., Margarita Gorlin, and Ravi Dhar. 2014. When Going Green Backfires: How Firm Intentions Shape the Evaluation of Socially Beneficial Product Enhancements. Journal of Consumer Research 41: 823–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, Mai Thi Tuyet, Linh Hoang Nguyen, and Hung Vu Nguyen. 2019. Materialistic values and green apparel purchase intention among young Vietnamese consumers. Young Consumers 20: 246–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, Kirsi. 2013. Sustainable Fashion: New Approaches. Helsinki, Finland: Aalto ARTS Books, Available online: https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/13769 (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Niinimäki, Kirsi. 2015. Ethical foundations in sustainable fashion. Textiles and Clothing Sustainability 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niinimäki, Kirsi, Greg Peters, Helena Dahlbo, Patsy Perry, Timo Rissanen, and Alison Gwilt. 2020. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nature Reviews Earth and Environment 1: 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niinimäki, Kirsi. 2011. From Disposable to Sustainable: The Complex Interplay between Design and Consumption of Textiles and Clothing. Ph.D. dissertation, Aalto University, Helsinki, Finland. Available online: https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/13770 (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Niinimäki, Kirsi. 2017. Fashion in a Circular Economy. In Sustainability in Fashion. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-51253-2_8 (accessed on 3 May 2017). [CrossRef]

- Sesini, Giulia, Cinzia Castiglioni, and Edoardo Lozza. 2020. New Trends and Patterns in Sustainable Consumption: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 12: 5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, Deirdre, and John Connolly. 2006. Identifying fair trade in consumption choice. Journal of Strategic Marketing 14: 353–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Dong, Joseph Richards, and Feng Liu. 2013. Consumers’ Awareness of Sustainable Fashion. Marketing Management Journal 23: 134–47. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Michael R., and Nancy J. Rabolt. 2004. Consumer Behavior in Fashion. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Michael R., Gary Bamossy, Soren Askegaard, and Margaret K. Hogg. 2006. Consumer Behaviour: A European Perspective, 3rd ed. Edinburgh Gate, Harlow and Essex: Prentice Hall Europe, Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhart, Yael, Ofira Ayalon, and Hila Puterman. 2013. The effect of an environmental claim on consumers’ perceptions about luxury and utilitarian products. Journal of Cleaner Production 53: 277–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The True Cost. ; Directed by Andrew Morgan. 2015. Documentary Film. Place of Distribution. Available online: https://truecostmovie.com/store/the-true-cost-digital-download (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Tunn, Vivian S. C., Nancy M. P. Bocken, Ellis A. van den Hende, and Jan P. L. Schoormans. 2018. Business Models for Sustainable Consumption in the Circular Economy: An Expert Study. Journal of Cleaner Production 212: 324–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Stuart. 2006. Sustainable by Design: Explorations in Theory and Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Chao, Pezhman Ghadimi, Ming K. Lim, and Ming-Lang Tseng. 2018. A literature review of sustainable consumption and production: A comparative analysis in developed and developing economies. Journal of Cleaner Production 206: 741–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, Marie, and Luis Martinez. 2018. Ethical consumer behavior in Germany: The attitude-behavior gap in the green apparel industry. International Journal of Consumer Studies 42: 419–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).