1. Introduction

With the help of the aims part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) promote, at a global level, the benefits and the importance of decent work for individuals, regions and countries alike (

United Nations 2015). Moreover, the advantages of full and productive employment and decent work are highly treasured by the Global Goals (GG) promoters, the focus being on encouraging economic growth with a particular emphasis on sustainability, sustainable development (SD), resilience and great concern for the environment (

United Nations 2022). Likewise, the International Labour Organization (ILO) avidly supports people’s right to decent jobs, under the conditions in which Guy Ryder—the International Labour Organization (ILO) Director-General, underlines in his vivid discourses that decent work represents more than a desire or a general objective, it signifies the very driver of sustainable development (SD) in today’s society (

ILO 2022a, p. 1).

What is more, quality education comes to support people’s desire to have access to decent and reliable job opportunities (

United Nations Geneva 2022). In turn, this leads to very deep connections between other pivotal desiderates found in the SDGs—known also under the form of partnerships for the goals, which are represented by: (a) individuals’ right to lead prosperous and harmonious lives in sustainable cities and communities, filled with equal opportunities for all (

United Nations 2018, pp. 12–13;

IZA 2017a); (b) regions and countries struggle to reach zero hunger levels for their inhabitants, facilitating access, in the same time, to affordable and clean energy by taking continuous climate action (

United Nations 2018, pp. 39–41); and (c) people’s need to have access to good health, sources of happiness, and well-being, supported by strong international justice systems and institutions capable to ensure peace on the long run (

Commonwealth 2015;

United Nations Geneva 2022).

Furthermore, the SDGs target sustained economic growth obtained, in particular, with the aid of higher levels of productivity which results from technological innovation and digitalization, in the context in which innovation has become a vital intangible asset (IA) for entities worldwide (

United Nations 2015). Besides these arguments painted above, important international organizations mentioned in the documents promoted globally the fact that decent work offers invaluable opportunities to individuals and economies, making reference to the following major issues: (a) first of all, inclusive and resilient economic growth is obtained with the help of decent work and decent jobs, since legal forms of employment implicate stronger social and economic systems (

United Nations 2018, pp. 39–41;

ILO 2022a, p. 1); (b) second of all, robust international policy-making systems are based on evolved and high-quality education systems which create real employment opportunities and which are capable to ensure change and living standards improvement (

United Nations 2018, pp. 39–41;

ILO 2022a, p. 1); and (c) third of all, inclusive international business environments are the ones that have the capacity to invest in individuals and in local communities thus fuelling growth and development by improving the employees working conditions, offering better paid positions, and providing more rewards to employees besides the financial ones (

ILO 2022a, p. 1).

Official figures, leaders, policymakers, researchers and specialists all around the world are constantly preoccupied to find solutions capable to ensure businesses’ performance, productivity, productivity growth, economic growth, and high living standards, not only in the case of emerging or developing economies, but also for the advanced economies (

OECD 2022a). In this matter, when it comes to addressing both social and environmental well-being, economists successfully pointed out, on numerous occasions, the fact that there are undeniable links between business performance, robust domestic policy settings, productivity, productivity growth, economic growth, living standards, inclusiveness, and innovation (

OECD 2022a).

Hence, for instance, a crucial part is played, at an international level, by the Global Forum on Productivity (GFP), which aims to show that countries ought to rely on promoting productivity-enhancing policies based on responsibility, sustainability, SD and an adequate work programme in accordance with individuals’ capabilities, competencies, and skills (

OECD 2022b).

In the same vein with the aforementioned issues, analysing the employment dynamics across different regions and countries should be carried out in a harmonised manner, centring on key factors, such as: the characteristics of the regions and countries targeted for the analysis; the human resources management (HRM) potential; the employees age, qualifications, level of education, desire to acquire new knowledge through training and additional studies, willingness to work, other social characteristics; and the entities capacity to innovate and to dedicate themselves to complex learning processes with the aid of digital transformations (DT) (

Desnoyers-James et al. 2019;

OECD 2022c). In continuation, numerous studies in the field stress that productivity growth and economic growth depend on the contribution made by science, technology and industry to the organizations’ development as well as on the individuals’ capacity to have access to new information and value knowledge (

OECD 2022d).

Along the same line, well-being seems to be responsible for people’s desire to dedicate more time to certain types of activities, such as: spending more hours working, in order to have access to better living conditions, thus increasing the living standards; spending more hours learning and perfecting the level of knowledge, in order to obtain better positions, evolve and advance faster at the place of work; spending more energy on learning new skills or perfecting the already existing ones, in order to be capable to promote creativity, innovation, and research (

OECD 2022d).

This current study is highly important in today’s general economic context, since it shows the advantages, benefits, and opportunities that can be obtained when individuals are willing to work more hours. The general question that seeks to be answered in this case is “Would you like to work more hours?” in the context in which financial rewards are offered to those people dedicating more time and effort to their jobs. The case of South Africa is closely analysed in this matter with the help of data belonging to the Quarterly Labour Force Survey that is conducted by Statistics South Africa. It ought to be added that this paper addresses a valuable and novel theme represented by people’s desire to dedicate more time working in return for financial incentives, thus contributing to increasing businesses performance, in a society severely affected by the changes and the challenges that were brought most recently by the COVID-19 pandemic and the COVID-19 crisis. The time frame selected for this paper starts from 2017 Quarter 1 to 2022 Quarter 2—which is the last published survey, which offers a tremendous opportunity to display the most recent data and analyse the most recent findings concerning the willingness of workers to work more hours if they are paid in the case of South Africa. In like manner, it needs to be emphasised that the advantages, benefits, and opportunities that can be reached when individuals are willing to work more hours are priceless when it comes to referring to the organization’s performance, especially in the case of people that choose to work more because they like their jobs, they feel appreciated for what they do, they are in the line of work that reflects best their skills and competences. Moreover, this study comes to support the values that individuals gain with the aid of education, since the findings managed to show that intellectual capital (IC) brings a particular advantage to organizations which makes them invaluable to the marketplace and which offers them the optimum competitiveness advantage that confers them unique traits while compared with other entities in the same line of business.

There numerous arguments that lead to choosing the case of South Africa for this research paper, among which could be mentioned the following ones: first of all, due to the desire to create an original analyses and a novel research paper, the decision was to focus on a group of countries or a country which usually receives less attention from scientists, in order to be able to make the best out of the data accessed in this matter and provide valuable insights on a subject capable to cover a significant research gap the field (

Duermeijer et al. 2018); second of all, since the two most pressing national problems with which South Africa confronts itself with are poverty and unemployment, the purpose was to find ways to tackle these pivotal issues in the context in which specialists mentioned that South Africa’s science system currently confronts itself with the biggest and vastest changes, challenges and risks in last 50 years (

Wild 2018); and third of all, according to recent valuable studies there are significant connections between individuals’ willingness to work more hours when additional payment is offered as reward and the people’s level of education, which led us to the necessity to find ways to show in which manner people can increase the national human capital in the case of South Africa, in order to raise business performance and foster national development (

Piet Sebola 2022).

This research, all in all, aims to identify what factors determine individual choice of working more hours. Broadly, the general research question was to explore those factors. To answer this question, data from South Africa which provides an important case country with the aforementioned risks and challenges faced are utilised. Therefore, findings from this special case are expected to be useful in policy development purposes.

The general structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 presents the general background, the literature review of the study, centring the attention on the most recent scientific works in the field that come to support the necessity to choose such a pivotal topic for the analysis;

Section 3 describes the materials and methods aiming aims to explore the willingness of workers to work more hours if they are paid in the case of South Africa;

Section 4 highlights the results of the paper and provides the empirical findings of the model introduced in the previous section;

Section 5 displays the discussion, conclusions, and recommendations.

2. Literature Review

The labour market indicators have the major purpose of displaying a wide range of employment data which may be specific to certain regions, countries, groups of regions, and/or groups of countries (

Federal Statistical Office 2022;

WEF 2022). These labour market indicators—which are believed to be crucial for any economy, since they have a very powerful effect on economic growth, sustainable development, and the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), are centred on the following main areas, namely: the specific details regarding the employment status of individuals, the working hours, the unemployment, the job vacancies, the dynamic aspects of the labour market with emphasis on the analysed region or country, as well as the salary structure (namely, the financial benefits that accompany certain jobs) and the general trends (

Federal Statistical Office 2022). Moreover, since each region and each country prides itself on valuable characteristics which make it unique, one way or the other, while compared with other regions and countries, human resources (HR) are seen by specialists as the key intangible asset (IA) that has the power to support the entities development and growth, which will lead, in time, to the growth of businesses’ performance in a sustainable and robust manner (

CE 2022;

Šebestová and Popescu 2022). Furthermore, today’s trends follow a specific international pattern which requires entities to align themselves to the SDGs, and to guide themselves after different very important rules and regulations that implicate the following crucial elements: the implementation at the level of organizations of green and sustainable finance, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Corporate Governance (CG), and business performance obtained with the help of green and sustainable finance processes, CSR, and responsible forms of CG (

Popescu 2019;

Popescu and Popescu 2019).

Moving on with our in-depth analysis, it ought to be promoted that Sustainability Assessment (SA) applies successfully to the labour market, especially in these days context, in which the leaders and the government’s concern goes far more than the need to ensure environmental protection (

Popescu 2020;

Sustainable Leaders 2022). Hence, SA intends to make a very thorough analysis of the causes that generated different degrees of development and growth at the level of organizations (

Popescu et al. 2015;

Popescu 2020). The general purpose of this SA is to establish, in the end, if we can discuss sustainability and sustainable development—targeted so eagerly by specialists at a global level, due to the need to satisfy the requirements of the present generations as well as the needs of future generations, without hindering the environment and without altering the living conditions of individuals (

Popescu et al. 2015;

Popescu 2020).

Moreover, besides SA it should be stressed that sustainability leadership plays a pivotal role when it comes to reflecting on the development specific to the labour market (

Popescu et al. 2017). In this matter, at a general level, sustainability represents, in the eyes of reputed scientists worldwide, a three-dimensional complex notion that covers three main areas, as follows: the economic processes, the social processes, and the ecological processes (

EC 2022b,

2022c). The first aspect that ought to be brought into discussion is the fact that the interconnectedness of all these economic, social and ecological processes is linked with the degree of development specific to the region or country placed under analysis, based on the fact that the rhythm of development and of growth specific to organizations and countries evolves differently depending on the economic, social, and ecological circumstances (

EC 2022b;

Popescu 2022). The second aspect that needs particular attention is the fact that, in this day and age, sustainable development means far more to society than environmental protection: on the hand, there is a distinct need for solidarity among people and among entities, especially in a society profoundly affected by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the COVID-19 crisis and, on the other hand, there is a stringent desire to ensure economic and social well-being in turbulent times such as the ones that our society and economy face (

Popescu and Popescu 2018;

WHO 2021;

EC 2022b). The third aspect that calls for immediate reflection is the fact that sustainability and sustainable development depend in a very profound manner on individuals’ capacity to get involved through their actions and their activity—in particular, in terms of the implications of the labour market in the development of any region and nation, thus being able to generate a structural change in both the social and the economic system (

EC 2022b,

2022c). All in all, the purpose is to lead, in time, to the creation of modern, sustainable and high-performing organizations as well as modern, sustainable and high-performing administrations capable to enable the following crucial elements: (a) an economy and a society capable to be reach high levels of performance in the Digital Age; (b) competitive human resources management (HRM) able to address the growing priorities of the employees as well as the constantly enlarging requirements of the employers; and (c) sound financial management capable to address the payment requirements of different entities, the risks that digital transformations brought in the society and the economy, and the logistic movements that take place at the level of organizations and between the entities (

EC 2022b,

2022c).

Each labour market has its particularities, which is a common trait for all markets, but in the case of the European labour market, for instance, there could be noticed significant changes in the last years, as follows: (a) first of all, there is a growing tendency to promote dialog and to foster communication methods between the employees and the employers in order to have a labour market oriented more towards enhanced communication practices and strategies, inclusiveness, openness, sustainability, and transparency (

WEF 2022); (b) second of all, there is a growing need to be part of European projects supporting COVID-19-related activities, measures and programs, in order to help people become more aware of the importance of health and safety in their lives and the lives of their dear ones (

CRS 2022;

European Movement International 2022); and (c) there is a constant concern to promote technological cooperation on the European labour market, under the circumstances in which new data transfer frameworks arrangements are in progress of being reached as a result of emerging technologies due to be implemented, security at the level of different technologies due to be accessed and used, and digital governance (DG) procedures due to be promoted (

CRS 2022;

European Movement International 2022).

According to reputed specialists worldwide, the processes of knowledge creation and human capital production are vital sources that are aimed at increasing national development (

Inglesi-Lotz and Pouris 2014;

Piet Sebola 2022). Moreover, the national labour markets are regarded as key resources for the national human capital development, which, based on researchers’ findings, should constitute exactly what an economy needs in order to occupy leading positions at an international level (

Masinde and Coetzee 2021;

Chankseliani et al. 2021). Based on these aspects, the complexity of each and every national labour market depends on the specific regions and countries taken under consideration, with the particular note, that besides the legislation stating the general framework for both the employees and employers, there are numerous categories of incentives that determine individuals to work more or to put more effort to the tasks given (

Murire and Cilliers 2017;

Muthama and McKenna 2020).

The International Labour Organization (ILO) pointed out that there are numerous paramount indicators (more exactly, 17 indicators of the labour market) which are specific to the labour market and that have to be carefully identified and valued especially when considering the achievement of the aims highlighted in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in an era that mainly relies on “data revolution”, digitalization, and DT (

ILO 2016). Among the most important indicators which are specific to the labour market, could be mentioned the following ones: (a) first of all, the labour force participation rate, which represents “a measure of the proportion of a country’s working-age population that engages actively in the labour market, either by working or looking for work” (

ILO 2016, p. 51); (b) second of all, the employment-to-population ratio which is presented as “the proportion of a country’s working-age population that is employed” and has the vital role of showing an economy’s capacity “to create employment” (

ILO 2016, p. 55); (c) third of all, the status in employment which is reflected by “two categories of the total employed”, namely, on the one hand, the “wage and salaried workers”, known as employees and, on the other hand, the “self-employed workers” (

ILO 2016, p. 61); (d) fourth of all, the employment by sector which makes reference to three main groups of individuals which can be encountered in agriculture, industry and services sectors, and which display the broad working activities that are known as well as the countries status of development (

ILO 2016, p. 65); (e) fifth of all, the employment by occupation which addresses the job classifications according to major groups embodied in the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) (

ILO 2016, p. 69); (f) sixth of all, the part-time workers which shows the “individuals whose working hours total less than “full time”, as a proportion of total employment” (

ILO 2016, p. 69); (g) seventh of all, the hours of work which offer a general picture concerning that the employed population “throughout the world devote to work activities” (

ILO 2016, p. 77); and eighth of all, other indications among which could be emphasised employment in the informal economy, unemployment, youth unemployment, long-term unemployment, time-related underemployment, persons outside the labour force, educational attainment and illiteracy, wages and compensation costs, labour productivity, and, also, poverty, income distribution, employment by economic class and working poverty (

ILO 2016, pp. 83–140).

Taking into account the aspects thoroughly displayed in the lines above, it ought to be prompted that the hours of work which offer a general picture regarding the time that the employed population “throughout the world” chooses “to devote to work activities” represent for this present study the key indicator specific to the labour market (

ILO 2016, p. 77). Hence, there are two characteristics that are crucial in this case, namely: one possible measure that offers valuable information regarding the hours that the employed individuals work during the week and another possible measure that brings pivotal insights on “the average annual hours actually worked per person” (

ILO 2016, pp. 77–81).

What is more, the Institute of Labour Economics (IZA) published invaluable discussion papers on the connections that can be encountered between working hours, employees’ performance and productivity (

IZA 2014,

2017b,

2018). Some of these important scientific works rely on data gathered using daily information on working hours, productivity and performance, while others on weekly or even annually information on working hours, productivity and performance (

IZA 2014,

2017b,

2018).

Furthermore, in order to demonstrate the major role played by the number of hours worked by employed personnel and the various connections discovered at the level of different entities worldwide, a selection of various findings of cardinal importance to the general objective of our current study are presented in the following lines. While analysing the links due to being encountered between working hours and the level of productivity by using daily information on the number of hours of work and the level of performance belonging to a sample of call centre agents, it has been shown that the more hours the employees spend at work, the more hours they were inclined to allocate per phone call received from potential clients, which led to a decreased level of productivity (

IZA 2014). Another work on munitions employees—where the main category of population chosen for the analysis is represented by female personnel, brings to light that at the beginning of the working program, the more hours individuals work, the more productive they seem to be; however, when the number of working hours increases (at the end of the program or when doing more hours than the usual time required), the employees tend to become tired, feel overworked, fail to be attentive by comparison with how they were at the beginning of the shift, which makes them more likely to get involved in accidents or get injured (

IZA 2017b). Interestingly, when attempting to analyse data covering the population of Danish workers based on the information gathered from the Danish Labour Force Survey (DLFS), specialists exhibit the fact that individuals’ success at the place of work and their chances to have access to better career opportunities tend to increase based on the working hours that they are willing to spend in order to improve themselves and facilitate their growing potential of advancement in hierarchy (

IZA 2018). In continuation, these specialists managed to come to the conclusion that there is a positive and undeniable connection between the number of hours worked by the employees, their capacity to get promoted and smoothly advance in career, and the increasing benefits of relying on human capital (HC) for the businesses performance (

IZA 2018).

The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) managed to put forward in a recent communication on “Working hours: latest trends and policy initiatives” people’s general concerns towards the number of hours spent at work, especially in the context in which more skilled employees belonging to the Anglo-Saxon countries want to dedicate more time to their families, being worried about the effects of long working hours on their health, well-being, and community life (

OECD 2022e, pp. 153–85). Nevertheless, in opposition to the aspects emphasised above, due to the fact that some European countries have confronted themselves in the last years with increased rates of unemployment, the tendency has grown towards the “work-sharing” policies which require less working hours per employees in order to facilitate the access of more individuals to employment facilities (

OECD 2022e, pp. 153–85). In the same line with these aforementioned issues, the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) also noted that people tend to become more and more aware of the importance of their jobs as well as of their job requirements, in terms of the “career prospects” that can be offered on the medium and long run (

OECD 2022e, pp. 153–85). Interestingly, even though our society confronts itself with severe social and economic disruptions in terms of the effects generated by the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID-19 crisis, a growing interest has been noticed lately in terms of making more flexible working programs for employees which ought to address “more wide-reaching changes in working arrangements”—including more online activities for the employees (

OECD 2022e, pp. 153–85).

In addition to the ideas laid out above, individuals’ willingness to work more hours if they are paid could also be the reflection of different levels of the economy—emerging, developing, or developed ones, the expected tendency among leaders and governmental official representatives being to encourage work in order to reduce inequalities, enhance the society’s inclusiveness, productivity and performance of labour markets, and achieve the 17 aims promoted by the United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (

Ellguth et al. 2014;

Devinatz 2015;

Global Deal 2020, pp. 3–4;

EC 2022a).

3. Materials and Methods

This paper aims to explore the willingness of workers to work more hours if they are paid in the case of South Africa. To do so, Quarterly Labour Force Survey that is conducted by

Statistics South Africa (

2022) is utilised (

Statistics South Africa 2022). The data set is publicly accessible through a free registration process from the DataFirst website which provides research data services from particular South Africa and other African countries. The time period chosen for this paper starts from 2017 Quarter 1 to 2022 Quarter 2 which is the last published survey. Each quarter is published separately on the website. However, those quarters from 2017 to 2022 were appended by authors for the purpose of this study.

The dependent variable is utilised from a survey question asking whether the respondent would like to work more hours if paid. This question is only asked to those who are employed. Answer categories are given as follows:

Yes, in the current job

Yes, in taking an additional job

Yes, in another job with more hours

No

Don’t know

First, those who do not know were dropped from the sample. Then, the variable is dichotomised, and answer categories are recorded from 1 to 3 as “1” willing to work more hours, and category 4 as “0” willing not to work more hours.

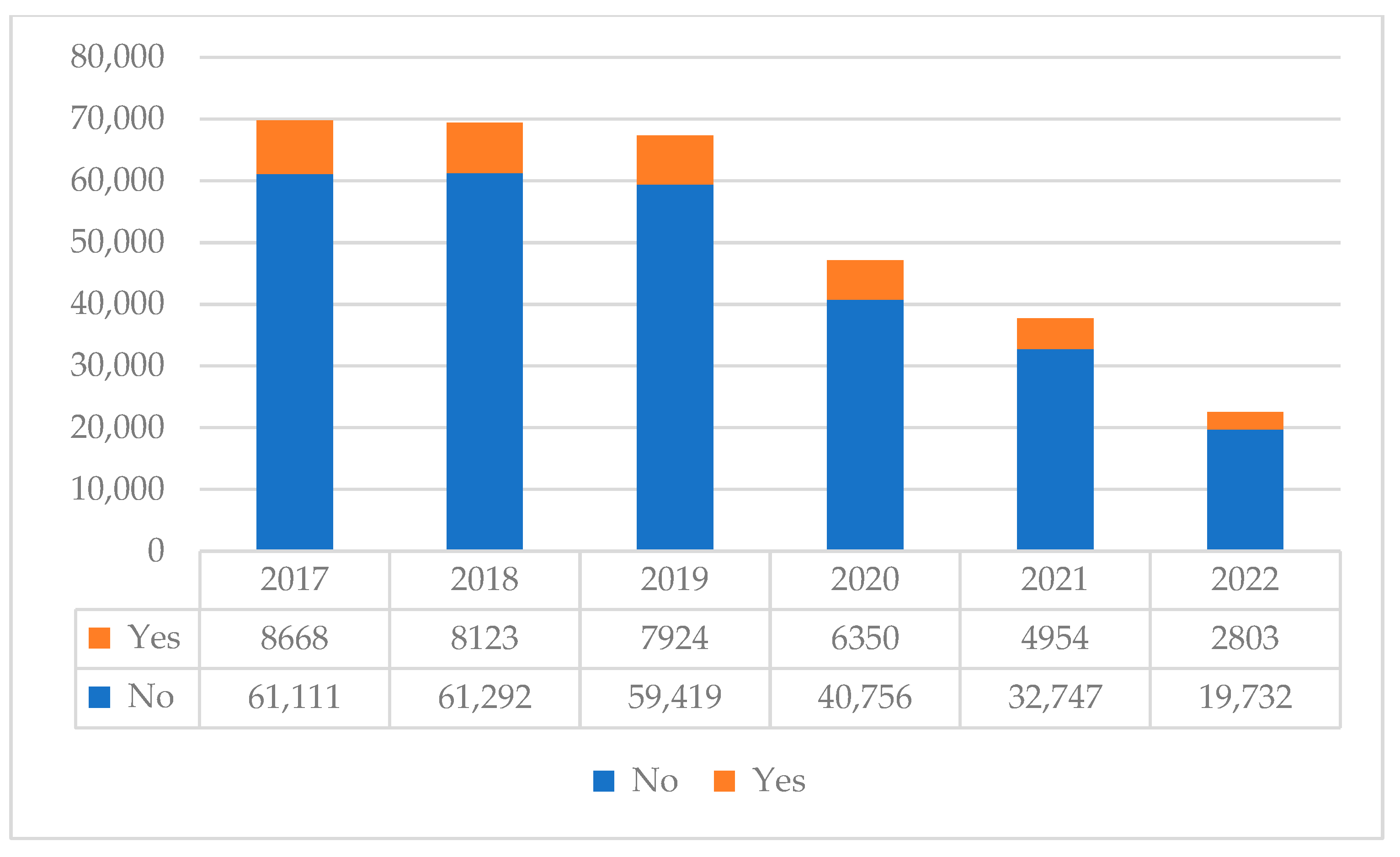

As presented in

Figure 1, there are 313,879 observations in total across years. Since there are only two quarters in 2022, it shows less numbers of observations. In terms of willingness to work more hours, the largest share of those who would like to work more hours if paid was found in the year 2020 with 13.5 per cent of the sample reporting “Yes”. The lowest share, however, was found in the year 2018 with 11.7 per cent.

Summary statistics of the dependent variable and independent variables used in the analysis are presented in

Table 1. Accordingly, 12 per cent of the sample seem to be willing to work more hours, while 87 per cent does not. In terms of distribution of gender in the sample, males constitute a larger share with 52 per cent in comparison to females with 47 per cent. Regarding marital status, most of the sample (i.e., 44 per cent) stated “never married”, while the second largest group (i.e., 37 per cent) is those who married. Education level of the survey participants varies across 7 education categories; however, they are mostly clustered in the group with secondary not completed (i.e., 34 per cent) and secondary completed (i.e., nearly 32 per cent).

Work experience is measured by the year the survey participant commenced working, not the number of years spent in work life. Therefore, the higher year shows lower work experience and vice versa. Nine provinces of South Africa are included in the survey. Gauteng province seems to have a larger population than other provinces. Nevertheless, it is hard to see a lop-sided distribution across those provinces. Finally, the time period of this investigation covers the last 6 years.

In order to test the willingness of individuals to work more hours if paid, a probit model is estimated as specified in Equation (1). Let MH

i be the outcome to be observed about preference towards working more hours by a respondent i.

where G is a dummy variable equal to 1 if male, MS is marital status, Edu is education level, Exp is work experience given by year commenced working. The model also includes controls for year, province, and their interaction to account for changes across provinces over years. The variable U is error term that contains unobserved factors affecting preferences on working more hours.

The Quarterly Labour Force Survey provides sample weight that allows us to have responses representing all South African population. Hence, in terms of weighting strategy, the sample weight that is provided in the survey was used. Since the model is a binary response model in which the dependent variable is a dichotomous variable, goodness of fit was measured through Pseudo R2 rather than R2 as in linear regression. Pseudo R2, hence, is used as a useful measure.

Analysing the factors affecting the work preferences of individuals is expected to provide a few benefits to South African society. First, what socio-demographic indicators significantly influence this behaviour would be identified. In a society where the output is well below the world average, this identification seems an important effort. Secondly, based on the findings, specific policies could be suggested such as gender-specific labour market regulations. Finally, in the light of findings, it could be possible to achieve an efficient labour market that is one key element of sustainable development.

4. Results

This research aims to identify what factors determine the individual choice of working more hours. The general research question which is to explore those factors is answered by using data from South Africa which provides an important case country with the aforementioned risks and challenges faced is utilised. Therefore, findings from this special case are expected to be useful in policy development purposes. Besides, potential societal benefits should also be mentioned. Identification of what socio-demographic indicators determine the willingness to work more hours, subgroup-specific policy suggestions, and efficiency purposes are expected to be crucial in this special case country. Considering the methodological preference in this investigation with 313,879 individual observations, this study is expected to contribute into a growing literature in Africa.

This section sheds new light on the manner in which the labour market should be regarded, especially when referring to the new social, economic, and ecological context generated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the COVID-19 crisis. In this matter, the labour market is extremely diverse and has its own particularities, depending on the region and the country under analysis. However, this current study displays results that might not only be specific to the case of South Africa, but might, also, be encountered in other parts of the world. It is of great importance to point out, in this context, that working more hours and being paid, at the same time, plays a crucial role in individuals’ decision to continue their activity, since they feel encouraged in a very successful way in those situations in which financial rewards are offered by the employers. Nevertheless, there are always other forms of rewards that are able capable to determine people to work more and to perform better, but these days financial rewards are pivotal in order to help individuals maintain a certain social status and maintain a certain desire to get involved at their jobs more than they usually do. Education is highly praised internationally—being distinctively addressed by the SDGs due to its distinctive position, and the level of education makes a great difference for individuals when being faced with making choices in terms of employment. In like manner, employers are faced with making different choices, when willing to hire new employees, based on people’s level of education.

This section provides empirical findings of the model introduced in the previous section as presented in

Table 2. The first column of

Table 2 presents the original coefficients obtained from the probit model. These coefficients can tell about the statistical significance and sign of the coefficient; however, the magnitude of a relationship is hard to draw from these raw coefficients. Therefore, to evaluate the size of the relationship between independent variables and dependent variables, the reference will be marginal effects that are presented in the second column of

Table 2.

Based on the findings, it can be said that there is a gender effect on the preference for working more hours. More precisely, being female increases the likelihood of willingness to work more hours if paid by 1.1 percentage points. This relationship is statistically significant at a 1 per cent significance level. Marital status of individuals was also found to be a significant indicator to explain this preference. Coefficients are all positive and statistically significant at a 1 per cent significance level, except for widow/widower with 10 per cent significance. The coefficients of never married and living together like husband and wife are almost the same, indicating that being never married or living together like husband and wife, rather than married, increases the probability of willingness to work by 2.6 percentage points. This probability is lower for those who are divorced or separated (i.e., 1.2 percentage points).

Education status of individuals is another significant indicator of their work preferences. While those individuals with less than primary or primary education, rather than no schooling, are more likely to work more hours if paid, those with an education level higher than primary are less likely to work more. The coefficient for individuals with tertiary education is the highest one. Having tertiary education decreases the probability of willingness to work more hours by 8.2 percentage points which is statistically significant at a 1 per cent significance level.

The variable of work experience is included if experience level influences individuals’ preferences for working more. It is seen that one more year to commence working increases the probability of willingness to work more hours which is significant at a 1 per cent level. Therefore, it might be said that less experienced employees are more likely to work more.

Figure 2 shows the size of the effect of each independent variable in a visual way that can help compare the magnitude of the effect easier. Those coefficients are obtained from the marginal effects of these variables.

Employees’ preferences for working more hours may differ between those who are satisfied with their work and those who do not. To test this possibility, this paper provides an investigation into those subgroups of employees. The Quarterly Labour Force Survey includes a question on whether the employed respondent is satisfied with her/his main job. Using answers (yes/no) to this question, we run the analysis for those who replied “Yes”, and those who replied “No”. The findings of this subgrouping are given in

Table 3.

As seen from

Table 3, the coefficient for females who are satisfied with their job is negative and statistically significant at a 5 per cent significance level, while it is positive for females who are not satisfied with their job. This implies that job satisfaction significantly influences females’ preferences for working more hours. When they are not satisfied with their main job, they are willing to work more; however, they do not want more hours if they are happy with their main job. Therefore, it can be said that the positive coefficient in the first specification presented in

Table 2 is driven by females who are not satisfied with their job.

Coefficients of marital status are larger in magnitude for those who are not satisfied with their main job. That means the likelihood of being willing to work more hours increases more for those who are not satisfied with their job and living together such as husband and wife or never married (rather than married) than those who are satisfied with their job. It should be noted that the relationship is still positive, although the size of the effect is larger in “not satisfied” group.

Interestingly, education levels of less than primary and primary completed were found not significant for those who are not satisfied with their job, while it is positive and significant for the other group. For those with an education above primary school, coefficients are negative and significant in both subgroups, except for those who did not complete secondary school and were satisfied with their main job. However, considering the magnitudes of the coefficients, it is seen that the probability of willingness to work more decreases more for those who are not satisfied with their job.

Work experience, finally, was found positive and statistically significant at a 1 per cent level though the magnitude of the coefficient is larger for those who are not satisfied with their main job. This means those who are not satisfied with their job and have relatively fewer years of work experience are more likely to work more hours.

5. Discussion, Conclusions, and Recommendations

The success of an inclusive and sustainable labour market can be reached in the context in which common frameworks exist and common assessment methods are in practice as follows: in this matter, in the public and in the private sector reference was made to very powerful and highly useful models, methods, and frameworks, such as the Common Assessment Framework (CAF), which is “a total quality management (TQM) model for self-assessment” that is capable to measure organizational performance and management performance, and that is capable to illustrate the benefits derived after applying different instruments at the organizations’ level that generate specific different organizational results (

EUPAN 2020). What is more, an inclusive and sustainable labour market centres on strong strategies and planning, performance results, and excellence both at work and in managerial practices (

EUPAN 2019,

2020). Furthermore, among the core values of the European labour market—which is characterised mainly by adaptability, diversity, and functionality, should be mentioned the following aspects: (a) firstly, the need to become more sustainable on the medium run and on the long run, with the help of the principles promoted by the circular economy, in order to be able to comply better with the Global Goals (GG) which make reference to the fast adaptation to climate change, the preservation of ecosystems, and the desire to maintain biodiversity for the next generations (

CENELEC 2022); (b) secondly, the need to become more flexible and more people-oriented, in order to offer a better working experience to both employees and employers, focusing on high standards of work, well-being, health, security, style and functionality (

WHO 2021); and (c) thirdly, the need to foster inclusion by centring on work practices that address and promote accessibility and affordability, hence encouraging individuals to paint a better future for all of us (

EC 2022d).

The World Health Organization (WHO) mentioned in the document “WHO European Framework for Action on Mental Health 2021–2025. Draft for the Seventy-first Regional Committee for Europe” the paramount fact that mental health is believed to be “an integral part of an individual’s capacity to think, emote, interact with others, earn a living and enjoy life”, which implicates that mental health comprises “the core human values of independent thought and action, happiness and friendship” (

WHO 2021, p. 1). What is more, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), people might be in serious danger and their mental health as well as their well-being might be at risk at their workplaces as a result of a wide range of factors, among which could be mentioned: the stress of the daily lives, the stress at work, the overwhelming tasks that mainly accompany individuals’ lives starting from their childhood stages and moving on to the adult stages, different types of crisis that generate instability and that generate different forms of social, economic, and political insecurity—namely, unemployment, disease outbreaks, epidemics, financial problems, recession and so on (

WHO 2021, pp. 1–19). Furthermore, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasises the vital role of leadership in taking action in order to ensure a certain balance at the places of work, in order to ensure an adequate working environment which should be friendly, warm, and fair, even though the business environment is highly competitive, demanding, and, in some cases, even quite aggressive (

WHO 2021, pp. 1–19;

WEF 2022).

When addressing the world’s biggest challenges—namely putting an end to global hunger and poverty, protecting our planet in a resilient and sustainable way, fostering a life of dignity for all individuals based on decent work and inclusive jobs, now more than ever before it becomes more and more clear that there exists a tremendous pressure on all people and on all entities, at a global level, to comply at with the 17 SDGs a rapid pace (

IOE 2016). Even though the times in which we are living are highly controversial, which significantly influences the way in which people line up their set of priorities as well as the aspirations that they have for themselves and for their families, having access to decent work and decent jobs will occupy an important place among the targets proposed to be accomplished now and in the future (

IOE 2016;

WHO 2019).

The results obtained in this new and original study are believed to provide key arguments for promoting individuals’ right to decent work, equal treatment in accessing decent jobs, and healthy working and living environments. The findings of this current scientific paper are vital when it comes to presenting the role of decent work and of decent jobs in our society as well as the importance played by education in gaining more opportunities to earn more money or to have access to more rewards.

There are numerous works that come to support the findings that we have displayed, especially in the context in which this study is of major importance when it comes to bringing arguments to support the achievement of the 17 SDGs.

In this matter, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) is an important supporter of the 17 SDGs, putting a particular accent on nations’ capacity to advance competitiveness with the aid of decent work, while focusing on “creating shared prosperity” for all and taking care of people’s health and environment’s well-being (

UNIDO 2015a). Since there are numerous arguments towards ensuring inclusive and sustainable industrial development (ISID) globally, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) noted the following elements: (a) firstly, the globalization of markets brings benefits both to consumers and to producers, which implicates that the effective integration of people in the new social, economic and environmental dimensions might be reflected by the need of employers to spend more hours working, in order to be able to comply in a more effective and efficient manner with today’s growing requirements coming mainly from managers and clients (

UNIDO 2015a); (b) secondly, the necessity to exclude inequalities from our society, by implicating both women and men from all countries in their job requirements by encouraging them to spend more hours working, especially when paid additionally or when offered additional rewards, led us to the belief that nobody should be left behind and all people should benefit from industrial growth (

UNIDO 2015a); (c) thirdly, individuals willingness to work more hours if paid might be associated not only with nations’ opportunity to offer their inhabitants access to decent work and inclusive jobs while making a contribution to industrial growth, but also with people’s common desire to create economic and social growth ultimately leading to “environmentally sustainable frameworks” (

UNIDO 2015b); and (d) fourthly, individuals willingness to work more hours if paid might be the result of people’s dedication to all the 17 SDGs in their quest to maximise in the best way possible the development impact generated by decent work and decent jobs, which could be reflected in the unique knowledge creating processes that are based on innovation, research, and investments in human resources (HR) and HC (

UNIDO 2015b).

There are numerous social benefits that can be encountered as a result of this current research due to the valuable nature of this study and the particularities of the case study chosen for analysis. First, the findings of this study come to support the results existing in the international specialised literature which place, as a top priority for organizations at a global level, human resources (HR), intellectual capital (IC), and intellectual property (IP). Second, this study emphasises the paramount influence that United Nations SDGs have on the labour market, since there are numerous pivotal areas that are profoundly influenced by the aims specific to the Global Goals (GG): on the one hand, the labour market is dependent on individuals’ level of health and the capacity to foster well-being and happiness and, on the other hand, the labour market is linked to the society’s capacity to transform information into key knowledge, hence ensuring access to quality education and training, equality at the place of work, decent possibilities to work, decent jobs, creativity, innovation, and scientific development. Third, this study is majorly dependent on the ability of leaders and managers to generate and maintain responsible behaviour, responsible activities, and responsible decisions in the labour market. To summarise, in other words, this novel and original study brings to the attention of individuals, entities, and leaders worldwide the importance of the opportunities embodied by the labour market especially in times of crisis, in delicate situations, that require particular attention in terms of social and economic needs. In this case, individuals’ desire and/or need to work more hours if paid, might have roots in different situations, such as, for instance: people’s necessity to become financially independent, employees’ desire to make themselves remarked through their work at their place of employment in order to have better chances to be promoted faster and in higher positions, or people’s inclination to feel needed and rewarded accordingly. In conclusion, the results of this study are very interesting and, at the same time, eye-opening, since they point out some of the particularities of the labour market in the case of South Africa: for instance, based on the data analysed, being female increased the likelihood of willingness to work more hours if paid by 1.1 percentage points; also, being never married increased that probability by 2.7 percentage points; moving on, within education categories, the highest coefficient in magnitude, having tertiary education decreases the probability of willingness to work more hours by 8.2 percentage points; furthermore, as an important labour market indicator, one more year to commence working increases the probability of willingness to work more hours if paid by 0.4 percentage points (see

Figure 3: The effects of working more hours if paid in today’s social and economic context).

In this context, it should be emphasised that this current study has certain limitations. One limitation is represented by the fact that the data analysed and discussed refers to the case of South Africa. Nevertheless, by comparing our findings with the results obtained by other researchers on data belonging to other regions, countries or groups of countries, it ought to be stressed that there are similarities, which makes us believe that there are valuable connections in terms of individuals’ willingness to work more hours if paid which do not necessarily depend on the origin (place, region, country) of the population selected. Another limitation is represented by the time period selected for the data analysed. Even though the time period selected might have been different, as long as the most recent data were selected for the analysis and discussed, the final results and the final comments on these results would have been similar, since in the last years’ humanity has confronted itself with many changes and challenges in terms of the COVID-19 pandemic, the COVID-19 crisis, and the most recent international conflicts which threaten the world peace and the general balance of our society as a whole.