Auditor Judgements after Withdrawal of the Materiality Accounting Standard in Australia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materiality Concept

2.1. International Perspectives

- U.S. Supreme Court: A fact is material if there is “a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would have viewed the… fact as having significantly altered the total mix of information made available” (U.S. Supreme Court 1976).

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission: “The term ‘material’, when used to qualify a requirement for the furnishing of Information as to any subject, limits the Information required to those matters about which an average prudent investor ought reasonably to be informed”. Auditors must ensure in the Management Discussion and Analysis section of the financial reports that public firms provide sufficient Information about matters that have significant financial implications (Roberson 2005; SEC 2005).

- Financial Accounting Standards Board: “The omission or misstatement of an item is material in a financial report, if, in light of surrounding circumstances, the magnitude of the item is such that it is probable that the judgement of a reasonable person relying upon the report would have been changed or influenced by the inclusion or correction of an item” (FASB 1980; Siegel 1980).

- U.S. Auditing Standards Board: “Misstatements, including omissions, are considered to be material if they, individually or in the aggregate, could reasonably be expected to influence the economic decisions of users made based on the financial statements” (ASB 2019).

- International Federation of Accountants: “Omissions or misstatements of items are material if they could, individually or collectively, influence the economic decisions of users taken based on the financial statements. Materiality depends on the size and nature of the omission or misstatement judged in the surrounding circumstances. The size or nature of the item, or a combination of both, could be the determining factor” (IFAC 2009).

- International Accounting Standards Board: “Information becomes material if omitting it or misstating it could influence decisions users make based on financial Information about a specific reporting entity. In other words, materiality is an entity-specific aspect of relevance based on nature or magnitude, or both, of the items to which the Information relates in the context of an individual entity’s financial report. Consequently, the Board cannot specify a uniform quantitative threshold for materiality or predetermine what could be material in a particular situation” (IFRS Foundation 2018). The definition was revised in 2018 as “Information is material if omitting, misstating or obscuring it could reasonably expect to influence decisions that the primary users of general-purpose financial statements make based on those financial statements, which provide financial information about a specific reporting entity” (IASB 2021).

- International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board: “Misstatements, including omissions, are considered material if they, individually or in the aggregate, could reasonably be expected to influence relevant decisions of intended users taken based on the subject matter information. The practitioner’s consideration of materiality is a matter of professional judgement and is affected by the practitioner’s perception of the common information needs of intended users as a group” (International Standard on Assurance Engagements—ISAE 3000) (IFAC 2011). “The auditor’s determination of materiality is a matter or professional judgment, and is affected by the auditor’s perception of the financial information needs of users of the financial statements. In this context, it is reasonable for the auditor to assume that users: have a reasonable knowledge of the business and economic activities and accounting and a willingness to study the Information in the financial statements with reasonable diligence; understand the financial statements are prepared, presented, and audited to levels of materiality; recognise the uncertainties inherent in the measurement of amounts based on the use of estimates, judgment and the considerations of future events; and make reasonable economic decisions on the basis of the Information in the financial statements. As explained in ISA 320, materiality and audit risk are considered when identifying and assessing the risks of material misstatement in classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures. The auditor’s determination of materiality is a matter of professional judgment and is affected by the auditor’s perception of the financial information needs of users of the financial statements (IAASB 2018). For the purpose of this International Standards on Auditing (ISA) and paragraph 18 of ISA 330, classes of transactions, account balances or disclosures are material if omitting, misstating or obscuring Information about them could reasonably be expected to influence the economic decisions of users taken on the basis of the financial statements as a whole” (ISA 315 Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement) (IAASB 2019, 2020).

- International Integrated Reporting Council: The report “should disclose Information about matters that substantively affect the organisation’s ability to create value over the short, medium and long term” (IIRC 2021).

- Centre for Corporate Governance: “Material information is any information which is reasonably capable of making a difference to the conclusions reasonable stakeholders may draw when reviewing the related information” (Centre for Corporate Governance 2016).

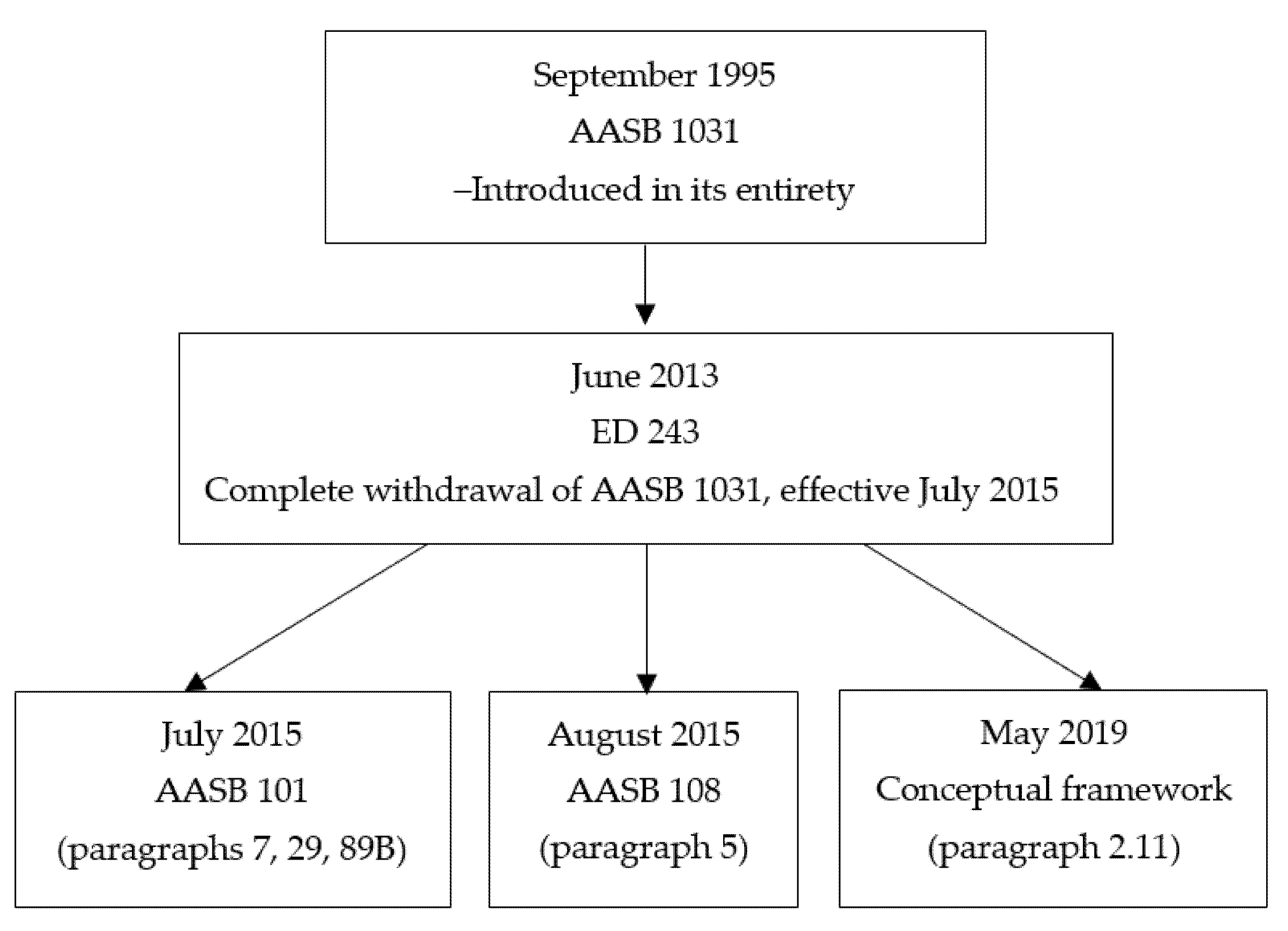

2.2. Australian Perspectives

- AASB 108 states that “Material omissions or misstatements of items are material if they could, individually or collectively, influence the economic decisions that users make based on the financial statements. Materiality depends on the size and nature of the omission or misstatement judged in the surrounding circumstances. The size or nature of the item, or a combination of both, could be the determining factor”, as noted in paragraph five (AASB 2015). AASB 101 states that “Material omissions or misstatements of items are material if they could, individually or collectively, influence the economic decisions that users make based on the financial statements. Materiality depends on the size and nature of the omission or misstatement judged in the surrounding circumstances. The size or nature of the item, or a combination of both, could be the determining factor” (see paragraph seven). The AASB 108 contains the same definition as stated in paragraph five (AASB 2018). AASB Framework states that “Information is material if omitting it or misstating it could influence decisions users make based on financial Information about a specific reporting entity. In other words, materiality is an entity-specific aspect of relevance based on nature or magnitude, or both, of the items to which the Information relates in the context of an individual entity’s financial report. Consequently, the Board cannot specify a uniform quantitative threshold for materiality or predetermine what could be material in a particular situation” (AASB 2016).

- Auditing and Assurance Standards Board: This is the materiality standard used in auditing to plan and perform an audit (paragraph two). “Misstatements, including omissions, are considered to be material if they, individually or in the aggregate, could reasonably be expected to influence the economic decisions of users taken based on the financial report; judgements about materiality are made in light of surrounding circumstances and are affected by the size or nature of a misstatement or a combination of both, and judgements about matters that are material to users of the financial report on the basis of the common financial information needs of users as a group. The possible effect of misstatements on specific individual users, whose needs may vary widely, is not considered” (AUASB 2015a).

3. Authoritative Standards and Guidance

3.1. Materiality before Withdrawal of AABS 1031 Materiality Accounting Standard

3.2. Nature and Amount in Materiality Judgement

- The amount alone is the determinant for error corrections.

- The amount determines the adjustments relating to events occurring after the balance date requiring adjustments.

- The nature of the item determines materiality about transactions occurring between an entity and parties who have a fiduciary responsibility about that entity. The Accounting Standard AASB 124 Related Party Disclosures outlines those events and transactions.

- The nature of the item determines the restrictions on the entity’s powers and operations that affect the risks and uncertainties. An example is laws imposed by governments on assets held in foreign countries.

- The nature of the item determined can change when an entity expands its operations into a new segment affecting risks and opportunities facing the entity.

- The nature of the item determines where the entity is in danger of breaching a financial covenant.

3.3. Other Quantitative and Qualitative Factors

- An amount equal to or less than 5 per cent of the appropriate base amount is presumed not to be material.

- An amount equal to or greater than 10 per cent of the proper base amount is presumed to be material.

- An amount greater than 5 per cent but less than 10 per cent is known as the “grey area”. Other factors such as the accounting treatment of different items in the same class of transactions or balances may establish treatment for financial statements.

- Other qualitative factors (paragraphs 17 and 18 of AASB 1031) were applicable under AASB 1031. These include:

- Financial restrictions under debenture deeds, debt convents or fiduciary duties of managers can make items less material than quantitatively indicated above.

- Changes in regular activities can turn a profit into a loss or create a margin of solvency in a balance sheet. These actions can focus on the materiality of revenue and expense items to the change in profit or asset revaluations that can reverse the solvency or net asset position.

3.4. After Withdrawal of the Materiality Accounting Standard in Australia

“Material omissions or misstatements of items are material if they could, individually or collectively, influence the economic decisions that users make based on the financial statements. Materiality depends on the size and nature of the omission or misstatement judged in the surrounding circumstances. The size or nature of the item, or a combination of both, could be the determining factor in planning and performing an audit”.

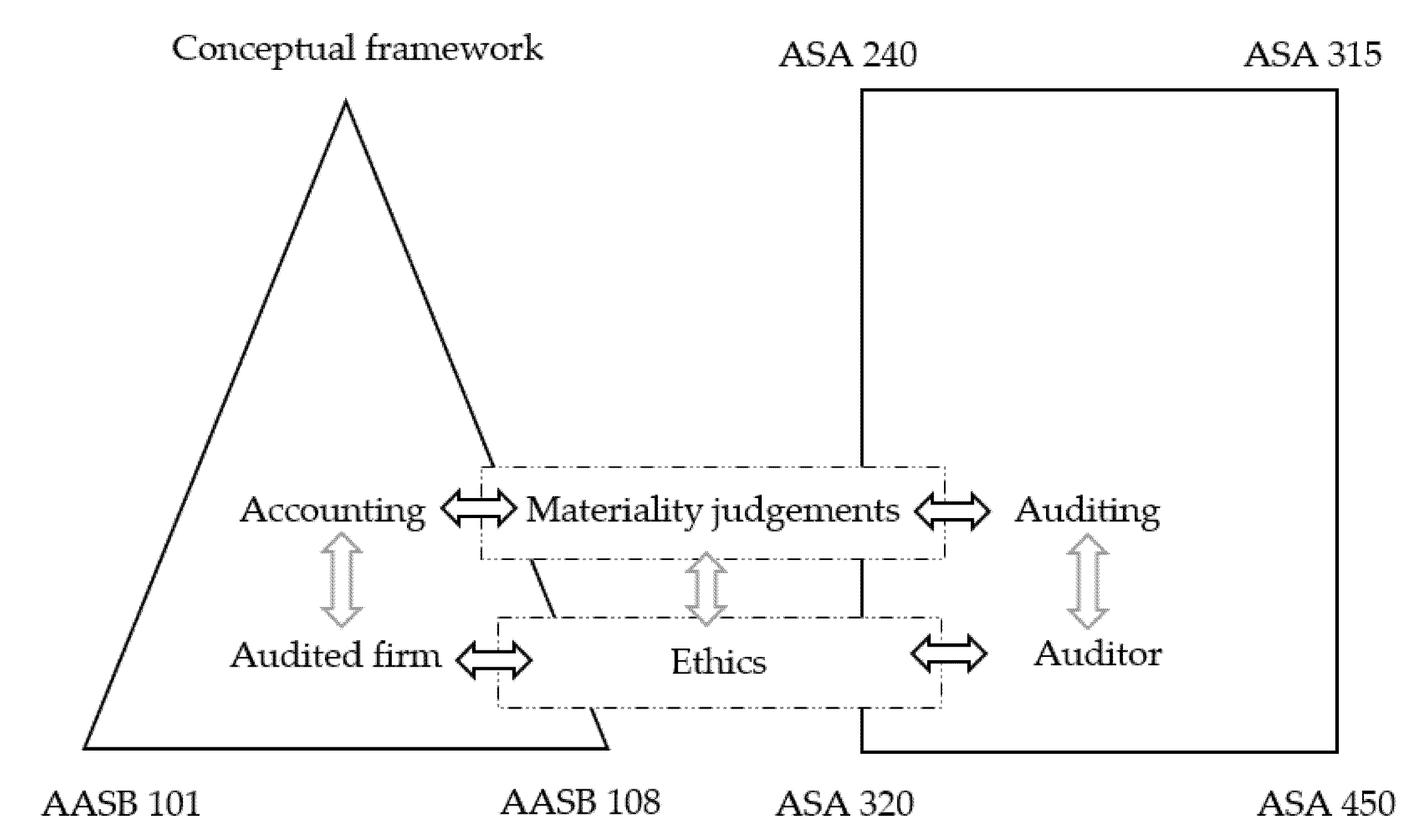

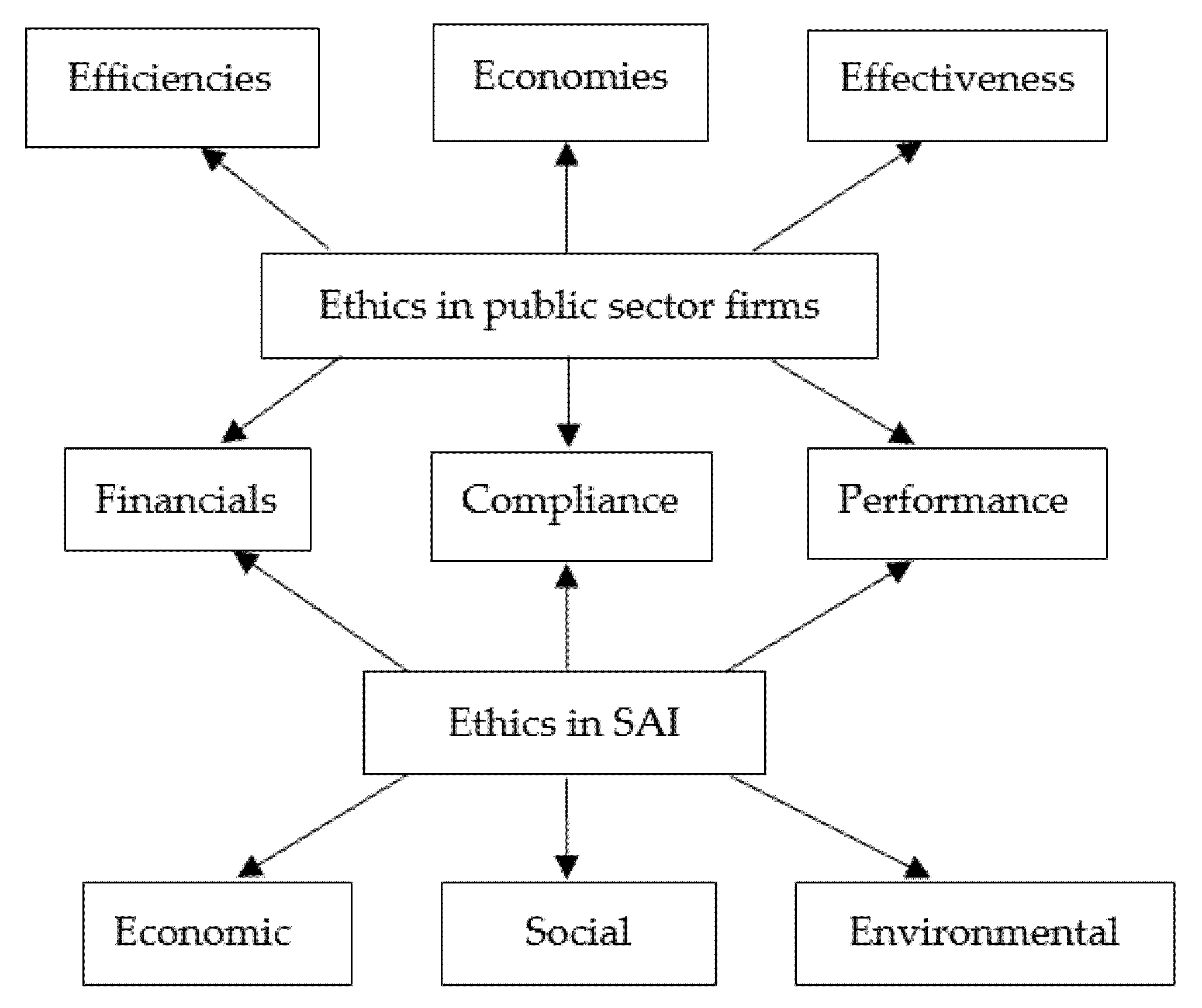

3.5. Role of Materiality in the Audit Process

4. Background Literature Informing Research Questions

4.1. Materiality Research Using Survey Questionnaires

- Are these heuristics of quantitative calculations of audit materiality still prevalent after the withdrawal of the AASB 1031 Materiality Standard?

- How do auditors evaluate misstatements that have been identified but not corrected, incorporating any qualitative factors influencing materiality assessments?

4.2. Materiality Research Using Archival Studies

4.3. Materiality Research Using Experimental Studies

4.4. Research Gaps in the Literature

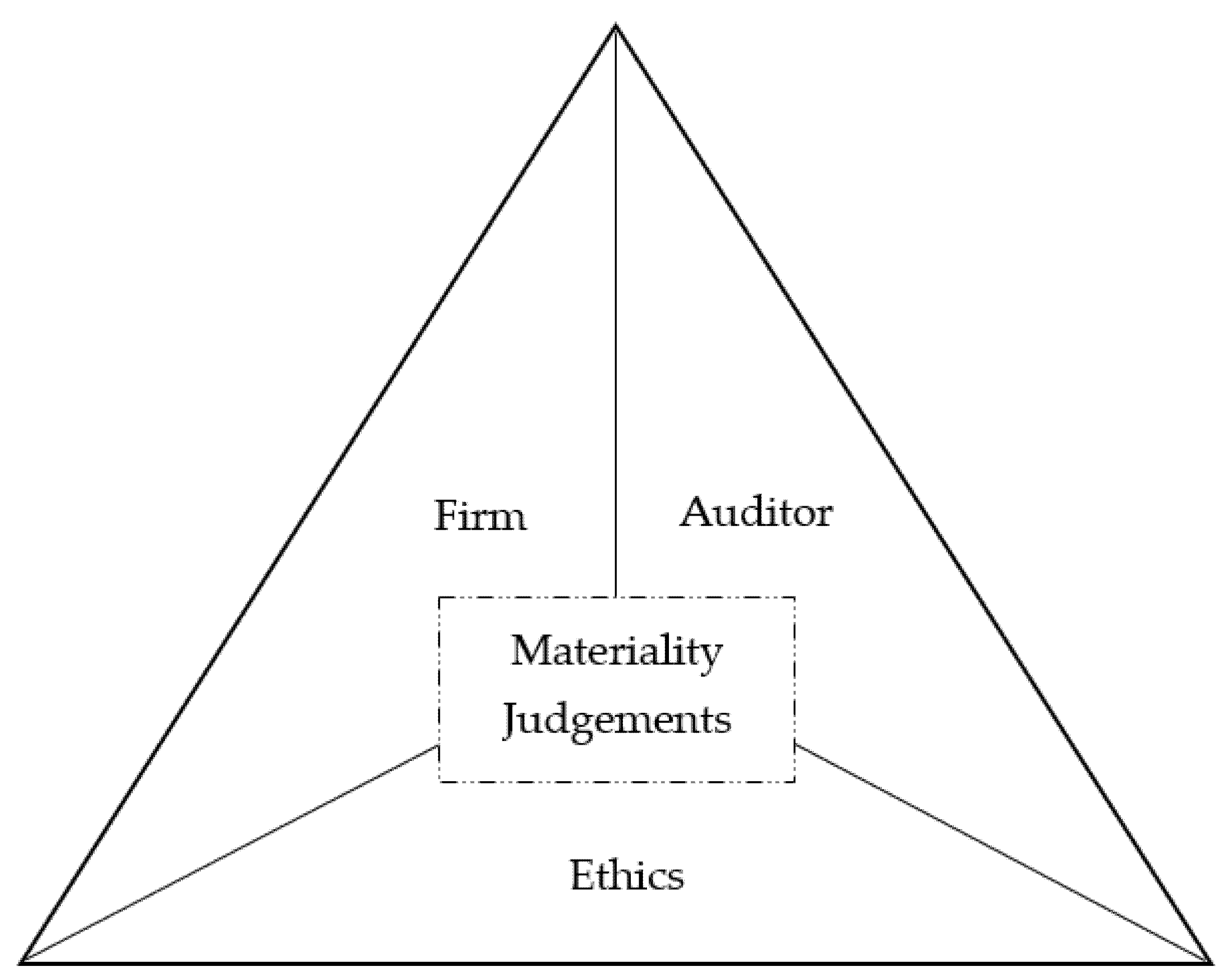

- Ethics

- To what extent do enterprise values systems influence materiality risk?

- To what extent do the CEO’s ethical standards influence materiality risk?

- Is there a relationship between the ethical wrongdoings of an enterprise and materiality risk?

- How ethical are audit firms conducting audits of the enterprise in determining materiality risk?

- Is there a relationship between auditor rotation cycle, audit partner duration of an audit, and setting materiality risks?

- Auditor

- How does an experienced auditor (fully competent—working with no supervision) differ from an inexperienced auditor (less than fully competent—working under supervision) in making materiality decisions?

- How do auditors assess materiality at different stages of an audit—planning stage, performance stage, and audit completion stage?

- How does an auditor identify tolerable errors and clearly trivial errors?

- How does an auditor evaluate misstatements at different stages (planning, performance, and completion) of the audit?

- How does an auditor evaluate omissions at different stages (planning, performance, and completion) of the audit?

- Audited Firm

- What are the key commonly-agreed indicators an auditor considers with respect to the risk level of Information?

- How does the CEO’s personality contribute to the materiality risks of an audit?

- To what extent does the group structure (a parent firm, subsidiary firm, associate firm, joint venture firm, investing firm) influence the materiality risk of an audit?

- To what extent does the overseas exposure of the firm (trading relationships, physical presence in another geographic area) influence the materiality risk of an audit?

- To what extent can an investing relationship in another geographic area influence the materiality risk of an audit?

- Auditor-Ethics-Firm TriangleThese are research questions pertaining to entire triangle:

- Do the auditor’s personal ethical standards moderate firm-level ethics in determining materiality judgements?

- To what extent can auditor dependence on the firm influence the application of ethics to materiality judgements?

- Do the frequency, duration, and currency of continuous professional development influence materiality judgements?

- Are there significant differences in materiality judgements between auditors completing the prescribed registration route versus alternative registration routes?

- To what extent does having an audit committee in firms moderate auditor materiality judgements?

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AASB. 1995. Accounting Standard AASB 1031 Materiality. Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB). Available online: https://www.aasb.gov.au/admin/file/content102/c3/AASB1031_9-95.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- AASB. 2013. ED243 Withdrawal of AASB 1031 Materiality. Australian Accounting Standards Board. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.aasb.gov.au/admin/file/content105/c9/ACCED243_06-13.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- AASB. 2015. Accounting Standard AASB 108 Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors. In Australian Accounting Standards Board. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.aasb.gov.au/admin/file/content105/c9/AASB108_08-15.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- AASB. 2016. Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements. In Australian Accounting Standards Board. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.auasb.gov.au/admin/file/content102/c3/Framework_07-04nd.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- AASB. 2017. Making Materiality Judgements. Complied AASB Practice Statement. AASB Practice Statement 2. Australian Accounting Standards Board. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.aasb.gov.au/admin/file/content102/c3/AASBPS2_12-17.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- AASB. 2018. Accounting Standard AASB 101 Presentation of Financial Statements. Australian Accounting Standards Board. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.aasb.gov.au/admin/file/content105/c9/AASB101_07-15.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Acito, Andrew A., Jeffrey J. Burks, and W. Bruce Johnson. 2009. Materiality Decisions and the Correction of Accounting Errors. The Accounting Review 84: 659–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acito, Andrew, Jeffrey J. Burks, and W. Bruce Johnson. 2019. The Materiality of Accounting Errors: Evidence from SEC Common Letters. Contemporary Accounting Research 36: 839–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, Donald F., Sr., Richard A. Bernardi, and Presha E. Neidermeyer. 2001. The Association between European Materiality Estimates and Client Integrity, National Culture, and Litigation. The International Journal of Accountancy 36: 459–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASB (Auditing Standards Board). 2019. Statement on Auditing Standards 138. Statement on Auditing Standards Amendment to the Description of the Concept of Materiality. Available online: https://www.aicpa.org/content/dam/aicpa/research/standards/auditattest/downloadabledocuments/sas-138.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- ASIC (Australian Securities and Investment Commission). 2021. Company Auditors. Available online: https://asic.gov.au/for-finance-professionals/company-auditors/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- AUASB (Auditing and Assurance Standards Board). 2006. Auditing Standard ASA240. The Auditor’s Responsibility to Consider Fraud in an Audit of a Financial Report. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2006L01368 (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- AUASB (Auditing and Assurance Standards Board). 2015a. Auditing Standard ASA 320. Materiality in Planning and Performing an Audit. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.auasb.gov.au/admin/file/content102/c3/ASA_320_Compiled_2015.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- AUASB (Auditing and Assurance Standards Board). 2015b. Auditing Standard ASA 315. Auditing Standard ASA 315. Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement through Understanding the Entity and Its Environment. Auditing and Assurance Standards Board. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.auasb.gov.au/admin/file/content102/c3/ASA_315_Compiled_2015.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- AUASB (Auditing and Assurance Standards Board). 2015c. Evaluation of Misstatements Identified during the Audit. Auditing Standard ASA 315. Auditing and Assurance Standards Board. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.auasb.gov.au/admin/file/content102/c3/ASA_450_Compiled_2015.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Bellandi, Francesco. 2018. Materiality in Financial Reporting. An Integrative Approach. Bingley: Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Leopold A. 1967. The Concept of Materiality. The Accounting Review 42: 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Blokdijk, Hans, Fred Drieenhuizen, Dan A. Simunic, and Michael T. Stein. 2003. Factors Affecting Auditors’ Assessments of Planning Materiality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 22: 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boatsman, James R., and Jack C. Robertson. 1974. Policy-Capturing on selected Materiality Judgments. The Accounting Review 49: 342–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bringselius, Louise. 2018. Efficiency, Economy and Effectiveness—But What about Ethics? Supreme Audit Institutions at a Critical Juncture. Public Money & Management 38: 105–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAANZ (Chartered Accountants Australia New Zealand). 2021. Codes and Standards. Australian Professional and Ethical Standards Board (APES) 110—Codes of Ethics for Professional Accountants. Available online: https://www.charteredaccountantsanz.com/member-services/member-obligations/codes-and-standards (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Cameron, Jonathan. 2014. Applying the Materiality Concept: The Case of Abnormal Items. Corporate Ownership & Control 12: 427–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Brian W., and Mark W. Dirsmith. 1992. Early Extinguishment Transactions and Auditor Materiality Judgements: A Bounded Rationality Perspective. Accounting, Organisations and Society 17: 709–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Corporate Governance. 2016. Statement of Common Principles of Materiality of the Corporate Reporting Dialogue. Available online: https://corporatereportingdialogue.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Statement-of-Common-Principles-of-Materiality.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Chewning, Gene, Kurt Pany, and Stephen Wheeler. 1989. Auditor Reporting Decisions Involving Accounting Principle Changes. Some Evidence on Materiality Thresholds. Journal of Accounting Research 27: 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chewning, Eugene G., Jr., Stephen W. Wheeler, and Kam C. Chan. 1998. Evidence on Auditor and Investor Materiality Thresholds Resulting from Equity-for-Debt Swaps. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 17: 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, Preeti, Kenneth Merkley, and Katherine Schipper. 2019. Auditors Quantitative Materiality Judgments: Properties and Implications for Financial Reporting Reliability. Journal of Accounting Research 57: 1303–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporations Act. 2001. Corporations Act 2001. Federal Register of Legislation. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2017C00328 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- CPAA CAANZ IPA (CPA Australia, Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand, and Institute of Public Accountants). 2015. Auditing Competency Standards for Registered Company Auditors. August. Available online: https://www.publicaccountants.org.au/media/628517/Auditing-Competency-Standard-FINAL-AUGUST-2015.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- DeZoort, F. Todd, Dana R. Hermanson, and Richard W. Houston. 2003. Audit Committee Support for Auditors: The Effects of Materiality Justification and Accounting Precision. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 22: 175–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirsmith, Mark W., and John P. McAllister. 1982. The Organic vs. the Mechanistic Audit. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance 5: 214–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, Kenneth M., and Rick Stapenhur. 1998. Pillars of Integrity: The Importance of Supreme Audit Institutions in Curbing Corruption. Washington, DC: The Economic Development Institute of the World Bank; The International Bank of Reconstruction and Development/World Bank, Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/199721468739213038/pdf/multi-page.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Edgley, Carla. 2014. A Genealogy of Accounting Materiality. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 25: 255–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilifsen, Aasmund, and William F. Messier. 2015. Materiality Guidance of the Major Public Accounting Firms. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 3: 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, John. 1997. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business, Capstone. Available online: http://www.trentglobal.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Triple-Bottom-Line.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Farneti, Federica, and James Guthrie. 2009. Sustainability Reporting by Australian Public Sector Organisations: Why they Report? Accounting Forum 33: 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FASB (Financial Accounting Standards Board). 1980. Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 2. Status. Qualitative Characteristics of Accounting Information. Available online: https://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Page/PreCodSectionPage&cid=1176156317989 (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Firth, Michael. 1979. Consensus Views and Judgment Models in Materiality Decisions. Accounting, Organisations and Society 4: 283–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frishkoff, Paul. 1970. Empirical Investigation of the Concept of Materiality. Empirical Research in Accounting: Selected Studies. Journal of Accounting Research 8: 116–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRI (Global Reporting Initiatives). 2021. The Global Standards for Sustainability Reporting. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Holstrum, Gary L., and William F. Messier Jr. 1982. A Review and Integration of Empirical Research on Materiality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 2: 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, Keith A., Christine Jubb, and Michael Kend. 2011. Materiality in the context of an Audit: The Real Expectation Gap. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 26: 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAASB (International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board). 2018. ISA 320 Materiality in Planning and Performing an Audit. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/downloads/a018-2010-iaasb-handbook-isa-320.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- IAUSB (International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board). 2019. ISA 315 (Revised 2019) Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/publications/files/ISA-315-Full-Standard-and-Conforming-Amendments-2019-.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- IAASB (International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board). 2020. ISA 220 (Revised). Quality Management for an Audit of Financial Statements. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/publications/files/IAASB-International-Standard-Auditing-220-Revised.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- IASB (International Accounting Standards Board). 2021. IFRS Practice Statement 2: Making Materiality Judgements. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/materiality-practice-statement/ (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- ICAEW (Institute of Chartered Accountants England and Wales). 2017. Materiality in the Audit of Financial Statements. Available online: https://www.icaew.com/-/media/corporate/files/technical/iaa/materiality-in-the-audit-of-financial-statements.ashx (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- IFAC (International Federation of Accountants). 2009. International Accounting Standard on Auditing 320. Materiality in Planning and Performance Audit. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/downloads/a018-2010-iaasb-handbook-isa-320.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- IFAC (International Federation of Accountants). 2011. ISAE 3000 (Revised), Assurance Engagements other than Audits or Reviews of Historical Financial Statements. International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/publications/exposure-drafts/IAASB_ISAE_3000_ED.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) Foundation. 2018. Definition of Materiality. Amendments to IAS 1 and IAS 8. IFRS Foundation. Available online: https://www.efrag.org/Assets/Download?assetUrl=%2Fsites%2Fwebpublishing%2FMeeting%20Documents%2F1709060818526684%2F04-05%20Definition%20of%20Material%20-%20Published%20Amendments%20-%20EFRAG%20TEG%2018-11-29.pdf&AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1 (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) Foundation. 2021a. IAS (International Accounting Standards) 1 Presentation of Financial Statements. IFRS Foundation. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-1-presentation-of-financial-statements.html/content/dam/ifrs/publications/html-standards/english/2021/issued/ias1/ (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) Foundation. 2021b. IAS (International Accounting Standards) 8 Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-8-accounting-policies-changes-in-accounting-estimates-and-errors.html/content/dam/ifrs/publications/html-standards/english/2021/issued/ias8/ (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- IIRC (International Integrated Reporting Council). 2021. Integrated Reporting. International Framework. Available online: https://integratedreporting.org/resource/international-ir-framework/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- INTOSAI. 2021. INTOSAI—International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions. Available online: https://www.intosai.org/ (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- INTOSAI (International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions) Journal. 2021. New Code of Ethics Adopted. International Journal of Government Auditing Feature Articles. Available online: http://intosaijournal.org/new-code-of-ethics-adopted/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Iselin, Errol R., and Takiah M. Iskandar. 2003. Auditors’ Recognition and Disclosure Materiality Thresholds: Their Magnitude and Effects of Industry. The British Accounting Review 32: 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, Takiah Mohd, and Erol R. Iselin. 1999. A review of Materiality Research. Accounting Forum 23: 209–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, Marianne, Dan C. Kneer, and Philip M. J. Reckers. 1987. A Reexamination of the Concept of Materiality: View of Auditors, Users, and Officers of the Court. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 6: 104–15. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, Edward J., and Robert Libby. 1982. Behavioural Studies on Audit Decision Making. Journal of Accounting Literature 1: 103–21. [Google Scholar]

- Keune, Marsha B., and Karla M. Johnstone. 2009. Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 108 Disclosures: Descriptive Evidence from the Revelation of Accounting Misstatements. Accounting Horizon 23: 19–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keune, Marsha B., and Karla M. Johnstone. 2012. Materiality Judgements and the Resolution of Detected Misstatements: The Role of Managers, Auditors, and Audit Committees. The Accounting Review 87: 1641–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, Rikke Holmslykke. 2015. Judgement in an Auditor’s Materiality Assessments. Danish Journal of Management & Business 79: 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad, Jack L., Richard T. Ettenson, and James Shanteau. 1984. Context and Experience in Auditors’ Materiality Judgements. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 4: 54–73. [Google Scholar]

- Martinov-Bennie, Nonna, and Peter Roebuck. 1998. The Assessment and Integration of Materiality and Inherent Risk: An Analysis of Major Firms’ Audit Practices. International Journal of Auditing 2: 103–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayper, Alan G. 1982. Consensus of Auditors’ Materiality Judgements and Internal Accounting Control Weaknesses. Journal of Accounting Research 20: 773–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayper, Alan G., Mary Schroeder Doucet, and Carl S. Warren. 1989. Auditors’ Materiality Judgements of Internal Accounting Control Weaknesses. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 9: 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- Messier, William. F. 1983. The effect of experience and firm type on materiality/disclosure judgements. Journal of Accounting Research 21: 611–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messier, William F., Nonna Martinov-Bennie, and Aasmund Eilifsen. 2005. A Review and Integration of Empirical Research on Materiality: Two Decades Later. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 24: 153–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, Gary Stewart, and David Woodliff. 1993. An Empirical Investigation of the Audit Expectation Gap: An Australian Evidence. Accounting and Finance 34: 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarity, Shane, and F. Hutton Barron. 1976. Modeling the Materiality Judgements of Audit Partners. Journal of Accounting Research 14: 320–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarity, Shane, and F. Hutton Barron. 1979. A Judgement-Based Definition of Materiality. Journal of Accounting Research 17: 114–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Mark W., and Hun-Tong Tan. 2005. Judgement and Decision Making Research in Auditing: A Task, Person, and Interpersonal Interaction Perspective. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 24: 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Mark W., Steven D. Smith, and Zoe-Vonna Palmrose. 2005. The Effect of Quantitative Materiality Approach on Auditor’s Adjustment Decision. The Accounting Review 80: 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, Fred. 1968. The Auditing Standard of Consistency. Journal of Accounting Research 6: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Terence Bu-Peow. 2007. Auditors’ decision on audit differences that affect significant earnings thresholds. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 26: 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, Alex. 2018. A General Theory of Social Impact Accounting: Materiality, Uncertainty and Empowerment. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 9: 132–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogler, George, and John Armstrong. 2013. How Auditors Get into Trouble—How to Avoid It. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance 24: 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Evelyn R., and Reed Smith. 2003. Materiality Uncertainty and Earnings Misstatement. The Accounting Review 78: 819–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PCAOB (Public Company Accounting Oversight Board). 2021. Auditing Standard Number 11. Consideration of Materiality in Planning and Performing an Audit. Available online: https://pcaobus.org/oversight/standards/archived-standards/pre-reorganized-auditing-standards-interpretations/details/auditing-standard-no-11_1767 (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Pierre, Jon, and Jenny de Fine Licht. 2019. How do Supreme audit Institutions manage their Autonomy and Impact? A Comparative Analysis. Journal of European Public Policy 26: 226–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, Brian K. 2005. Statement by SEC Staff: Remarks before the 2005 AICPA National Conference on Current SEC and PCAOB Developments. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/spch120505bkr.htm (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- SEC (U.S. Securities Exchange Commission). 1999. SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin: No 99—Materiality. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/interps/account/sab99.htm (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- SEC (U.S. Securities Exchange Commission). 2005. Record of Proceedings. Securities and Exchange Commission Advisory Committee on Smaller Public Companies. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/info/smallbus/acspc/acspctranscript092005.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- SEC (U.S. Securities Exchange Commission). 2013. Report on Review of Disclosure Requirements in Regulation S-K. As Required by Section 108 of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/files/reg-sk-disclosure-requirements-review.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Siegel, Marc. 1980. For the Investor: Disclosure Effectiveness. How Materiality Fits In. FASB (Financial Accounting Standards Board). Available online: https://www.fasb.org/cs/ContentServer?c=Page&cid=1176167771326&d=&pagename=FASB%2FPage%2FSectionPage (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Sims, Ronald R., and Johannes Brinkmann. 2003. Enron Ethics (Or: Culture Matters More Than Codes). Journal of Business Ethics 45: 243–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Malcolm, Brenton Fiedler, Bruce Brown, and Joanne Kestel. 2001. Structure versus Judgement in the Audit Process: A Test of Kinney’s Classification. Managerial Auditing Journal 16: 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Frederick Hendrik, Francois Retief, and Reece Alberts. 2021. The evolving role of Supreme Auditing Institutions (SAIs) towards enhancing Environmental Governance. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 39: 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapenhurst, Rick, and Jack Titsworth. 1991. Features and functions of Supreme Audit Institutions. Prem Notes. No. 59. Public Sector. The World Bank. Available online: http://www1.worldbank.org/prem/PREMNotes/premnote59.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Steinbart, Paul J. 1987. The Construction of a Rule-Based Expert System as a Method for Studying Materiality Judgements. The Accounting Review 62: 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, Kenneth W. 1981. Future Directions in Auditing Research. The Auditor’s Report Summer: 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Jerry D. 1984. The Case for the Unstructured Audit Approach. Retrieved from University of Kansas. Available online: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1157&context=dl_proceedings (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- U.S. Supreme Court. 1976. TSC Industries, Inc., Petitioners, v. Northway, Inc., Justia. U.S. Supreme Court. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/426/438/ (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- UNDP (United Nations Development Program). 2021. The SDGS in Action. What Are Sustainable Development Goals? Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Wang-On-Wing, Bernard, J. Hal Reneau, and Stephen G. West. 1989. Auditors’ Perception of Management: Determinants and Consequences. Accounting, Organisations and Society 14: 577–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Bart H. 1976. An Investigation of the Materiality Construct in Auditing. Journal of Accounting Research 14: 138–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WASB (Water Accounting Standards Board). 2012. Australian Water Accounting Standard 1. Preparation and Presentation of General Purpose Water Accounting Reports. Bureau of Meteorology. Australian Government. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/water/standards/wasb/documents/Water-Accounting-Conceptual-Framework-Accessible.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Woolsey, Sam M. 1954. Development of Criteria to Guide the Accountant in Judging Materiality. Journal of Accountancy 97: 167–73. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

David, R.; Abeysekera, I. Auditor Judgements after Withdrawal of the Materiality Accounting Standard in Australia. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060268

David R, Abeysekera I. Auditor Judgements after Withdrawal of the Materiality Accounting Standard in Australia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021; 14(6):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060268

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavid, Raul, and Indra Abeysekera. 2021. "Auditor Judgements after Withdrawal of the Materiality Accounting Standard in Australia" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 6: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060268

APA StyleDavid, R., & Abeysekera, I. (2021). Auditor Judgements after Withdrawal of the Materiality Accounting Standard in Australia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(6), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060268