Abstract

This paper describes the development of a chatbot as a cognitive user interface for portfolio optimization. The financial portfolio optimization chatbot is proposed to provide an easy-to-use interface for portfolio optimization, including a wide range of investment objectives and flexibility to include a variety of constraints representing investment preferences when compared to existing online automated portfolio advisory services. Additionally, the use of a chatbot interface allows investors lacking a background in quantitative finance and optimization to utilize optimization services. The chatbot is capable of extracting investment preferences from natural text inputs, handling these inputs with a backend financial optimization solver, analyzing the results, and communicating the characteristics of the optimized portfolio back to the user. The architecture and design of the chatbot are presented, along with an implementation using the IBM Cloud, SS&C Algorithmics Portfolio Optimizer, and Slack as an example of this approach. The design and implementation using cloud applications provides scalability, potential performance improvements, and could inspire future applications for financial optimization services.

1. Introduction

In financial decision making, optimization is one of the most critical techniques. Since the development of the mean-variance portfolio optimization method that was introduced by Markowitz (1952), both research and practice in finance have become increasingly technical Cornuejols and Tütüncü (2006). While individual investors could potentially benefit from optimizing their portfolios, this would require significant financial literacy Collins (2012), the ability to represent investment preferences as an optimization problem, knowledge of the underlying optimization models, coding techniques to solve the optimization problem, and interpretation of the optimal solutions. These requirements represent a significant barrier preventing individual investors from utilizing optimization techniques.

Most self-service investment advisory tools provide assistance in constructing an investment plan by matching the investor’s surveyed risk aversion level with a pre-defined standard portfolio from a set of potential portfolios. These portfolios usually differ only in the composition of stocks, bonds, etc. Investors who do not have complete knowledge of the underlying model and financial markets could find it difficult to incorporate their investment preferences into optimized portfolios. Even for experienced financial advisors, including investment preferences, such as minimizing the exposure to specific industries within the optimization formulation, can be challenging. For example, an investor could have the preference to invest in financial instruments that are associated with higher sustainability or ethical scores. With the appropriate data available, this could be included in the optimization formulation as a target minimum ESG score. The current automatic investment advisory tools that are available are not flexible enough to reflect these common investment preferences in the suggested portfolios.

Individual investors without the required background to construct their own investment portfolios could use financial advisory. Traditional financial advisory could be defined as the provision of professional financial advice for individuals who seek assistance or want to completely delegate their investment decisions Fischer and Gerhardt (2007). Cocca (2016) summarizes the process of financial advisory within private banking, including an analysis of the investment needs and objectives of the client, incorporating the client’s risk profile and defining an investment strategy for asset class allocation. This process relies heavily on the experience and skills of the advisors, especially for the identification and formulation of investment needs and preferences. Empirical studies that were conducted by Montmarquette and Viennot-Briot (2019) and Harlow et al. (2020) show that investors who seek financial advisory could better achieve their investment goals, such as investing for retirement, when compared to those who do not use advisory services. Although these services can be beneficial, individual investment preferences are usually not addressed properly in this process. Additionally, advisory services are usually associated with a relatively high cost of service due to significant labour requirements to manually reflect the different preferences in the underlying optimization model. Most existing high scale and low-cost portfolio construction and optimization services are limited to benchmark portfolios, usually consisting of only ETFs, and do not enable individual investors to incorporate preferences other than risk aversion levels or investment horizons. Examples of such benchmark portfolios include target-date funds and online investment advisors, such as Acorns Advisers and BMO SmartFolio. With these tools, users cannot incorporate their objectives and industry based preferences into their investments. Therefore, investors could find these services to be convenient, but hard to customize. Additionally investors cannot incorporate their existing portfolio holdings into these services. There is a lack of high scale and low-cost portfolio construction options which also allow for individual customization available to investors.

Our paper and design of the cognitive user interface for portfolio optimization aims to fill this gap. The goal of our design is to allow users to express their investment preferences using natural language, creating a similar experience to receiving financial advisory services, while maintaining scalability. When compared to the automatic investment advice services that are currently available in online banking and investing, this solution provides the flexibility to accommodate a wide range of investment preferences, in addition to the risk profile and return expectations. The cognitive user interface allows users to directly interact with the online portfolio optimizer, similarly to how they would interact with a human financial advisor (for example, by email or face-to-face talks). This would be beneficial for both the service provider and the users. One typical cognitive user interaction deployment is the integrated system of chatbots. With the recent rapid development of machine learning techniques, chatbots are increasingly used in different areas, including online education da Silva Oliveira et al. (2019); Memeti and Pllana (2018); Goel et al. (2016); Ranoliya et al. (2017); Clarizia et al. (2018), automated customer care Xu et al. (2017); Cui et al. (2017); Nuruzzaman and Hussain (2018), automated basic personal finance service Okuda and Shoda (2018), health care support Cameron et al. (2017); Su et al. (2017), etc. It would be natural and easy for users to accept this format when we extend the application of chatbots to financial optimization.

In this paper, the design and an example of a deployment method for using a chatbot as a cognitive user interface for portfolio optimization are discussed. This paper is organized, as follows. First, Section 1 provides a background on portfolio optimization in traditional financial advisory and cognitive user interfaces such as chatbots, motivating the usage of chatbots for portfolio optimization. Section 2 introduces the existing platform and cloud applications used to build the financial portfolio optimization chatbot. Section 3 describes the methodology for extracting the information required to form an optimization problem from natural text input from users, the communication with the backend optimizer, and the conversation interface. Section 4 presents a deployed prototype of the system described in this paper. Finally, Section 5 discusses the properties of the system and draws conclusions.

2. Related Work

In this section, the two cloud applications IBM Watson Assistant and SS&C Algorithmics Portfolio Optimization Service used in the system design and deployment are introduced.

2.1. Chatbot and the IBM Watson Assistant

When deployed on a cloud server, Chatbots pass the request of the user to the server and provide a response to the user’s request after being activated with keyword capturing Hoy (2018). Various types of chatbots have been developed since the introduction of the idea. Social chatbots mainly interact with users and generate proper responses that provide an emotional connection to the user and satisfy the communication needs of the users Colby et al. (1971); Wallace (2009); Weizenbaum (1966); Zhou et al. (2020). Question and answering chatbots aim at discovering knowledge from a given collection of documents and to provide answers to users’ inquiries Chen et al. (2016); da Silva Oliveira et al. (2019); Ranoliya et al. (2017).

During the emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic, chatbots have been developed and deployed to share up-to-date information, encourage healthy behaviors, assess and control risks, and provide emotional support in multiple languages Martin et al. (2020); Miner et al. (2020). This also indicates an increasing public acceptance of professional advice being communicated through chatbots.

Various works have studied the customer segments that are more likely to use chatbots. Brandtzaeg and Følstad (2017) and Rese et al. (2020) identify the key factors that motivate users to use a chatbot as an interaction interface: timely and efficient service, extended service opening time, low cost, and curiosity about new technologies. Some users even perceive chatbots to be more reliable than their human counterparts. On the other hand, limited technology access and doubts about reliability and quality from other user segments act as deterrents to the adoption of chatbot technology.

The evaluation of chatbot performance is relatively complicated and multiple metrics are proposed to standardize the user’s experience with the chatbot Przegalinska et al. (2019); Lee et al. (2018); Jenkins et al. (2007). Unlike social chatbots, the performance of task-oriented chatbots cannot be fairly evaluated by the length of the conversations. Instead, the completion of service and user satisfaction would be a more direct and useful metric. Scalability would be an important metric for cognitive financial optimization because one core advantage of developing and deploying chatbots is the ability to provide service to a large number of users simultaneously. As Lui and Lamb (2018) identified, trust and confidence are the core of wide scale acceptance of automated financial services.

Watson is a popular exemplification of cognitive computing systems Kelly III and Hamm (2013); Ferrucci (2012) and Watson is receiving increasing attention in applications and research Goel et al. (2016); Chen et al. (2016); Memeti and Pllana (2018); Murtaza et al. (2016). Built using natural language understanding techniques and algorithms, Watson Assistant provides an easy way to build, train, deploy, and test conversational applications with multi-language support. Constructing a chatbot with IBM Watson Assistant is divided into three tasks: defining user intents and supplying each intent with training examples, identifying contextual terms (entities), and designing a conversation flow with pre-set chatbot responses. Training the machine learning model with examples is automated with the cloud application and the model can be easily updated by adding or removing training examples. Entity matching supports multiple matching patterns, including regular expressions, exact matching, and fuzzy matching. The conversation flow design provides a user-friendly graphical interface and it supports randomly picking responses to improve the flexibility of the conversation and the user’s experience with the chatbot. The cloud RESTful API (application programming interface) enables the integration of IBM Watson Assistant’s chatbot service into the design of a larger cognitive computing system. Developers could update the training set of the model and interact with the trained chatbot using only the backend. Model configuration, including the training set, intents, entity definitions, and conversation flow design could be easily stored and transferred using structured JavaScript Object Notation (JSON).

Employing a chatbot as a cognitive user interface would help to decrease the average cost of providing portfolio selection services. The total economic impact from the IBM Watson Assistant report shows a significant cost saving per contained conservation with Watson Assistant.

There are also other development and deployment tools for chatbots provided by other cloud infrastructure providers such as Dialogflow on Google Cloud, Azure Bot Services on Microsoft Azure, and AWS Chatbot on Amazon Web Services.

2.2. SS&C Algorithmics Portfolio Optimization Service

Mathematical optimization is a type of quantitative algorithm that is used for financial and risk-aware decision making. Optimization problems frequently solved in finance include wealth management, asset allocation, portfolio selection, risk management, regression problems, hedging, and pricing of derivatives. An overview of financial optimization can be found in Cornuejols and Tütüncü (2006) and Romanko and Mausser (2017).

The SS&C Algorithmics Portfolio Optimization service deployed on IBM Cloud is an online cloud application that translates the expressions of structured JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) into an algebraic form, applies adjustments, reformulates optimization problems in the most efficient manner to reduce solution time, scales optimization problems to improve numerical stability, and after that calls IBM ILOG CPLEX solver to solve the obtained formulation. This optimization service can be easily deployed on IBM Cloud or any other cloud by creating containerized instances and interacting with the RESTful API through Python, R, Matlab, Java, or curl.

Many optimization problems in finance are multi-objective by nature, as they involve minimizing a portfolio risk measure while maximizing a portfolio reward indicator. One of the classical portfolio selection models that involve a risk-reward trade-off is the mean-variance portfolio optimization problem formulation that was introduced by Harry Markowitz (1952). In this paper, we use extensions of mean-variance optimization within a multi-objective portfolio selection framework, where absolute or relative variance serves as a risk measure and expected return serves as a reward measure.

Let us consider a typical financial portfolio optimization problem. We denote the asset weights in a portfolio by , i.e., is the proportion of total funds invested in asset i, where . An expected return vector for assets is denoted by , where . A variance-covariance matrix of returns is denoted by Q, where (positive semidefinite). A typical formulation of the mean-variance optimization problem minimizes portfolio variance of returns while constraining the expected return to be at least target value R:

In formulation (1), a risk measure , i.e., portfolio variance of return, is minimized subject to the constraint that a reward measure (expected return ) exceeds a prescribed bound R, and other operating constraints are satisfied. Constraints on asset holdings are usually assumed to be in the presence of no-short-sales restrictions. We can also solve problem formulations when arbitrary linear constraints on asset weights in the portfolio are specified. In this paper, we assume that is a set of continuous linear constraints or mixed-integer linear constraints.

While the typical risk measure to be minimized is portfolio variance , alternative risk measures can be specified. The tracking error squared risk measure is a portfolio variance of return relative to a benchmark portfolio with asset weights in the benchmark being . By minimizing the portfolio tracking error (or equivalently, tracking error squared) we would like to minimize the mean squared error between our portfolio returns and returns of a benchmark portfolio. The typical benchmark portfolio is a market index, but, in general, it can be any fixed portfolio. When variance is used as a risk measure, the portfolio selection strategy is referred to as active. When tracking error is used as a risk measure, the portfolio selection strategy is referred to as passive. In addition to variance and tracking error risk measures, tail risk measures, such as value-at-risk Romanko and Mausser (2016) and conditional value-at-risk at a quantile level , are also supported. More advanced portfolio selection strategies, such as risk parity Mausser and Romanko (2014) and portfolio replication Burmeister et al. (2010), can also be incorporated.

In contrast to active portfolio selection strategies which have the form (1), passive portfolio selection strategies have the form:

where portfolio tracking error squared is minimized subject to constraints.

Both active investing and passive investing strategies can be optimized using the SS&C Algorithmics Portfolio Optimization service. For active investing problems of type (1), one could optimize a mixture of risk and return by minimizing risk and adding a constraint to specify the lower bound of the expected return at a given time. For passive investing problems of type (2), a pre-set or user-defined benchmark portfolio is added to reflect the typical user’s risk profile and investment horizon. For variance-covariance matrices, the service supports both the parametric approach, by specifying the estimated covariance matrix, and the non-parametric approach, by defining a scenario set to calculate variances and covariances from (including Monte Carlo scenario sets, historical scenario sets, and stressed scenario sets).

A universe of around 200 assets is pre-loaded to the SS&C Algorithmics Portfolio Optimization service. It includes stocks, equity ETFs, and fixed-income ETFs. Data for this universe of assets are also pre-loaded. The variance-covariance matrix Q and the expected return vector are estimated from historical returns or from a factor model. If necessary, users can bring their own data to the service via the same RESTful API interface.

Optimization constraints are derived from investor preferences by the chatbot and they are expressed in the form of linear equalities and inequalities:

Investor preferences for portfolio selection can include the following categories and are expressible in the form of a set (3):

- sectors, such as IT, health care, energy, real estate, and consumer staples;

- environmental, sustainability, controversy, governance, and social priorities (in many cases referred to as ESG preferences);

- excluding sin investments from consideration such as fossil fuels, military, gambling, tobacco, or alcohol;

- allocating to domestic investments vs. foreign investments; and,

- diversification preferences and no-short-sales restriction.

This list can be expanded, if necessary.

JSON API syntax for expressing objective functions and constraints was designed to support optimization formulations of the type (1) and (2), among others. Multiple objective functions are supported, as well as constraints beyond the form (3). In addition, the JSON API syntax was designed to resemble natural language in order to be able to be generated by natural language processing algorithms, such as chatbots. An example of such API request in JSON format for specifying objective functions and constraints is shown below:

"objectives": [{

"sense": "minimize",

"measure": "variance",

"attribute": "return",

"portfolio": "Universe",

"targetPortfolio": "Benchmark",

"timestep": 30,

"description": "minimize tracking error squared (variance of the difference between

Universe portfolio and Benchmark returns) at time 30 days"

}],

"constraints": [

{

"attribute": "weight",

"members": "Universe",

"relation": "greater-or-equal",

"constant": 0,

"description": "no short-selling of assets from the Universe portfolio"

},

{

"attribute": "weight",

"members": "Universe",

"relation": "less-or-equal",

"constant": 0.1,

"description": "weight of each asset from the Universe portfolio does not exceed 10%"

},

{

"attribute": "weight",

"portfolio": "Has Military",

"inPortfolio": "Universe",

"relation": "equal",

"constant": 0,

"description": "exclude all assets that have property Has Military"

},

{

"attribute": "weight",

"portfolio": "Has Tobacco",

"inPortfolio": "Universe",

"relation": "equal",

"constant": 0,

"description": "exclude all assets that have property Has Tobacco"

},

{

"attribute": "weight",

"portfolio": "High Environmental Score",

"inPortfolio": "Universe",

"relation": "greater-or-equal",

"constant": 0.5,

"description": "weight of assets with High Environmental Score in the portfolio

should be greater-or-equal than 50%"

},

{

"attribute": "weight",

"portfolio": "Industrials",

"inPortfolio": "Universe",

"relation": "greater-or-equal",

"constant": 0.2,

"description": "weight of Industrials in the portfolio should be greater-or-equal than 20%"

},

{

"attribute:": "value",

"portfolio": "Universe",

"cashadjust": 10000,

"description": "cash inflow of 10000 monetary units to the Universe portfolio"

}]

Using an API request, SS&C Algorithmics Portfolio Optimization service returns a structured JSON-formatted response that includes asset holdings of the optimal portfolio (if an optimal solution exists), objective function value, solution statistics (solution quality, slack variables, etc.), and timestamps of receiving the request and returning the results. A subset of fifty assets from the trading universe was used for integration with the chatbot service. For such problem sizes, the service returns results within seconds.

The JSON-formatted response that is returned by SS&C Algorithmics Portfolio Optimization service is post-processed by the chatbot system, and optimal positions in each instrument are saved into a csv file that can be submitted to a trading system. We also implemented a validation procedure for optimal portfolios, currently only some of the validation results are reported to the user by the chatbot. For instance, in the optimal portfolio example that is discussed in Section 4, the chatbot is able to report the objective function value (the tracking error with respect to the benchmark portfolio) and confirm to the user that the portfolio value is $10,000, which corresponds to the invested amount. ESG properties of an optimal portfolio (environmental score, sustainability score, governance score, controversy score, and social score) are also computed and visualized. In the implementation example in Section 4, it is confirmed that the portion of assets with High Environmental Score within the optimal portfolio is greater than or equal to 50%, as specified by the constraint. Other user preferences, e.g., that tobacco stocks are excluded, are also validated, and can be reported back to the user.

While the cloud portfolio optimization service largely reduces the cost for end users, as they do not need to code an optimization algorithm and, to select a suitable solver, the API user interface is still quite complex for an individual investor. While the web-based graphical user interface (GUI), which sits on the top of the API interface, can help with the service usability, but it is also quite demanding. Both interfaces (API and GUI) require a user to possess extensive financial literacy knowledge and understanding of the optimization modelling. The API interface additionally requires basic coding skills.

Replacing the API and GUI with a chatbot interface greatly simplifies and streamlines user experience for individual investors. It would also bring wealth management and robo-advising web-platforms to a new level of user experience.

3. Methods

In this section, we discuss the method that is used to extract information for the optimization formulation from a user’s natural text input. Financial optimization chatbots require an efficient method to accurately translate the text or voice natural language input into a well-defined mathematical expression that can be interpreted by the optimizer service. More importantly, the chatbot is expected to identify the aspects of investment objectives or preferences that the user is discussing, and collect the key parameters mentioned in these inputs. If such parameters are not clear or missing, then the chatbot needs to confirm its understanding and either return the result to the user or engage with the user to input missing information. For simplicity, the chatbot requires the user to express different investment preferences in different sentences and this requirement is hinted to the users in the welcome message.

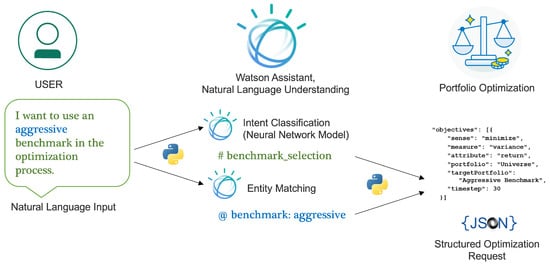

Figure 1 shows how the inputs in natural language format are processed within the cognitive portfolio optimization system. The input is first being classified into underlying intents using the intent classifier (discussed in Section 3.1), and contextual terms using the entity matching model (discussed in Section 3.2). The processed output is then stored and handled using global variables and, after all of the inputs are processed, the optimization problem is formulated using these stored values in global variables (Section 3.3) and a request is sent to the portfolio optimization service described in Section 2.2. After processing each input and receiving the result from the portfolio optimizer, a natural language response is returned to the user to confirm preferences, request additional information, and provide help and instructions. The system then summarizes the optimization preferences and results, and then visualizes the properties in the optimized portfolios while using the conversation management system (Section 3.4).

Figure 1.

Example of the processing of a natural language input in financial optimization.

3.1. Intent Classification

Intent classification serves as the core of cognitive handling of natural language input. When the input from the user is received, the intent classifier identifies the purpose behind the input and which aspect of investment preference the language is referring to. The intents used in our implementation are listed in the Table 1 below:

Table 1.

The list of pre-defined intents and their relationship with the optimization problem formulation.

For each of the intents above, the training set was constructed while using a mixture of email interactions between investors (the users) and financial advisors, and augmented texts providing examples of investment preferences. The accuracy of this classification problem is important for improving user experience.

In addition to all of the intents listed above, an ’other’ intent is also included to capture the case where none of the above intents is identified with a defined threshold of confidence. Furthermore, all of the responses from the users indicating a request to change the intent classified are recorded. Both of these inputs can be used to improve the accuracy of the classifier in the early development and testing stage of the chatbot.

3.2. Entity Matching

As discussed in Section 2.1, entities are the contextual terms and keywords that the cognitive computing system tries to identify from user inputs. For financial portfolio optimization, the entities that are listed in Table 2 are defined and the entity matching model is trained to match and mark them in the input:

Table 2.

The list of entities and their relationship with the optimization problem formulation.

3.3. Global Variables and Optimization Problem Formulation

Global variables are defined to store the identified optimization preferences (objectives, constraints) and the current status of the conversation. For each detected intent that is directly related to optimization problem formulation that is listed in Section 3.1, the Python backend searches for the required entities identified in the input. If all required entities exist in the user’s input, then the value of entities and type of objective formulation related to the intent will be stored in the global variables. If any of the necessary entities are missing, then an indicator would be activated to help the chatbot to record the relevant intents and state of the conversation. The chatbot could then request the user to input the missing entities and add to the in-progress optimization formulation.

After all of the inputs are added to a request summarizing the optimization problem, the Python algorithm in the backend validates the inputs to ensure that the optimizer is not missing any required information.

The goal of the Python backend is to format all global variables as a request that the portfolio optimizer can interpret. In the case of using SS&C Algorithmics Portfolio Optimization service that is discussed in Section 2.2, this would mean formulating a structured JSON request.

3.4. Conversation Management

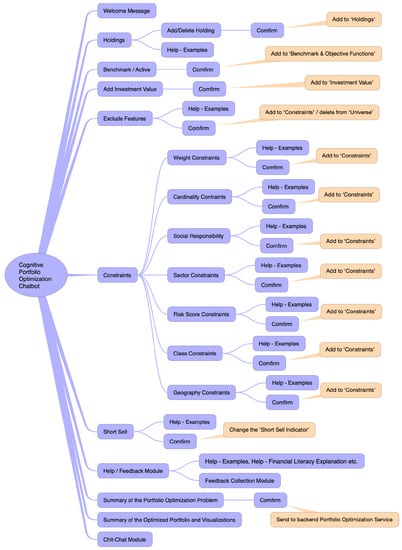

One advantage of using a chatbot as the user interface is that the interaction is easy and natural for users. This includes a warm welcome and provides instructions on the available functions and system usage, confirming the processed investment preferences and entities mentioned, asking for further information when needed, communicating the optimization settings, and sharing results with the users. To achieve this, the chatbot could use a pre-set conversation manager that controls the chatbot responses. An example of such conversation manager is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The design of conversation flow in the portfolio optimization chatbot deployed using IBM Watson Assistant.

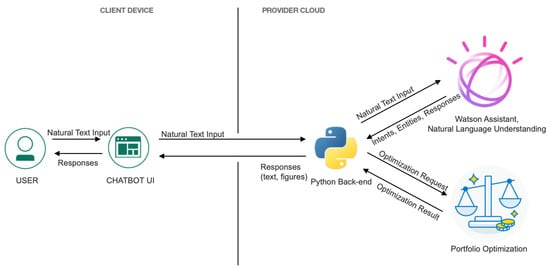

3.5. System Design

Figure 3 summarizes the overall design of the cognitive user interface for portfolio optimization. The user interacts with the chatbot user interface using natural language input and receives responses in text, voice, or visualization. This process is executed on the client’s personal device. The chatbot user interface forwards the natural language user input to the Python backend and the cloud application to be processed by the intent classifier, the entity matching model in the natural language understanding application on the cloud, and then the Python backend stores the extracted investment preferences and provides a response back to the chatbot using the conversational management system. The Python backend, natural language understanding application, and underlying optimization service applications are deployed on the service provider’s cloud.

Figure 3.

The system design of the portfolio optimization chatbot deployed using IBM Cloud.

The stored global variables containing the entire profile of investment preferences could be encrypted and stored upon the user’s request in order to re-evaluate the portfolio, perform re-balancing, and make other adjustments. It is equivalent in information to have either all of the stored global variables or the JSON assembled request. Both of them include all the necessary elements for the mathematical formulation in the underlying optimization model. As a result the optimization could be done using an iterative approach over a period of time. This implementation demonstrates how the proposed system could store and manage a user’s portfolio over an extended period of time, updating the portfolio optimization formulation with the user’s latest preferences.

3.6. Paragraph Handling

Being inspired by the common and virtual practice of communicating investment preferences and optimized portfolio allocations through email, the framework described above could be easily extended to other cognitive computing applications. For example, instead of having a conversation through the chatbot user interface, the user could summarize all investment preferences in a single paragraph. The paragraph in text or voice can be directly processed by the intent classifier and entity matching model with proper parsing algorithms. This interface would be more efficient, since all of the investment preferences are handled at once, but lacking support and interaction would require the users to have a certain level of financial literacy that is higher than for the chatbot interface. There would also be limited opportunities to confirm inputs or ask for additional information.

4. Implementation

The portfolio optimization system and chatbot interface that are discussed in Section 3 were deployed for testing and a prototype is presented in this section.

For training and deploying the intent classifier and entity matching model, the IBM Watson Assistant that is described in Section 2.1 is used. SS&C Algorithmics Portfolio Optimization service (Section 2.2) is used as the underlying portfolio optimization problem solver. Along with the Python backend, the service provider cloud components are completed and deployed. For the chatbot user interface, Slack is used for users to interact with the chatbot.

Figure 4 shows a conversation between the user and the chatbot. In this conversation, the chatbot is able to chat with the user, providing greetings and friendly interactions, such as introducing itself. It is able to recognize investment objectives, such as the investment horizon, and when it is not sure about the exact investment horizon, the system generates a follow-up question, prompting the user for additional details. It can also generate optimization constraints, such as adding cash infusion, excluding certain types of assets, and targeting an overall social responsibility score within the constraints. Before submitting the formulated optimization problem, a summary of the objectives and constraints is presented to the user. After submitting to the backend optimizer and retrieving the result, the chatbot summarizes the optimized portfolio and provides visualizations to the user.

Figure 4.

An example of a conversation between user and the deployed portfolio optimization chatbot.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Using a chatbot as the user interface for portfolio optimization represents an example of how advances in natural language processing can be used to enhance the availability of optimization tools for individual investors. Our implementation uses a deep learning model to determine the user’s intent from each input, and matching models to identify any specific entities mentioned. The backend then structures all of the inputs into an optimization problem which is handled by an optimization solver. The conversation management model within the chatbot then generates natural language responses and visualizations using the optimization results, which are communicated back to the users.

Implementation using a mature cloud service ensures the stability of the interface as well as improves its scalability when handling requests from a large number of users. The online training of the core models, such as the intent classifier, could help improve the performance of the chatbot after deployment using users’ feedbacks.

Our work in this paper considers the design of a system using a cognitive interface for portfolio selection. Future considerations include measuring the performance and accuracy of such a system. Evaluating the performance includes gaining user feedback on the conversation flow to determine how effective the conversation management module is at guiding conversations. Ensuring that the chatbot is accurate in interpreting users’ intents is important, as it could be difficult and even unrealistic for users to validate themselves if the optimized portfolio is truly optimal for them and does satisfy their investment goals. Both of these elements need to be further studied to measure the performance of our proposed system.

The chatbot interface is significantly more flexible than existing survey methods for automatic portfolio selection; however, as the chatbot relies heavily on training examples to interpret user input, the regular maintenance of the training examples could be required. For the purpose of this work, we considered a finite set of possible user intentions, as described in Section 3.1. To further enhance the flexibility of the framework, the system design could allow professional and institutional users to upload instrument universe datasets to include sectors, industry classification, and other asset level information that reflects the preference of users. The framework that we present can integrate with optimization models of varying complexity. In the future, this work can be extended to explore models of greater complexity, including multi-period optimization models, tax-aware portfolio optimization models, and other risk measures by updating or changing the underlying model in the portfolio optimization service and adjusted intents, entities, and conversation flow design of the chatbot. These extensions could be explored in future work.

Future extensions to this work could include extending the input process capabilities to include natural text inputs with multiple optimization preferences. This could be addressed by building the classifier to first predict the number of intents in the input and then output the best predictions on several possible intents. This process could be combined with entity identification to better predict multiple intents in a single sentence and match the corresponding entities for each intent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.R., Y.H. and R.K.; methodology, Y.H., O.R., A.S., R.K. and R.S.; software, Y.H., O.R. and R.S.; resources, O.R. and R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H. and O.R.; writing—review and editing, A.S., R.K., R.S., O.R. and Y.H.; visualization, Y.H., O.R. and R.S.; supervision, O.R and R.K.; project administration, O.R.; funding acquisition, O.R. and R.K.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Mitacs [49601] under Mitac Globalink Research Internship Program.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mitacs Globalink Internship Award (49601) under the Mitacs Globalink Research Internship Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brandtzaeg, Petter Bae, and Asbjørn Følstad. 2017. Why people use chatbots. In International Conference on Internet Science. New York: Springer, pp. 377–92. [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister, Curt, Helmut Mausser, and Oleksandr Romanko. 2010. Using trading costs to construct better replicating portfolios. In 2010 Enterprise Risk Management Symposium Monograph. Schaumburg: Society of Actuaries, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Gillian, David Cameron, Gavin Megaw, Raymond Bond, Maurice Mulvenna, Siobhan O’Neill, Cherie Armour, and Michael McTear. 2017. Towards a chatbot for digital counselling. Paper presented at the 31st International BCS Human Computer Interaction Conference, Sunderland, UK, 3–6 July; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ying, JD Elenee Argentinis, and Griff Weber. 2016. Ibm watson: How cognitive computing can be applied to big data challenges in life sciences research. Clinical Therapeutics 38: 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarizia, Fabio, Francesco Colace, Marco Lombardi, Francesco Pascale, and Domenico Santaniello. 2018. Chatbot: An education support system for student. In International Symposium on Cyberspace Safety and Security. New York: Springer, pp. 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Cocca, Teodoro. 2016. Potential and limitations of virtual advice in wealth management. Journal of Financial Transformation 44: 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Colby, Kenneth Mark, Sylvia Weber, and Franklin Dennis Hilf. 1971. Artificial paranoia. Artificial Intelligence 2: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J Michael. 2012. Financial advice: A substitute for financial literacy? Financial Services Review 21: 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornuejols, Gerard, and Reha Tütüncü. 2006. Optimization Methods in Finance. 5 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Lei, Shaohan Huang, Furu Wei, Chuanqi Tan, Chaoqun Duan, and Ming Zhou. 2017. Superagent: A customer service chatbot for e-commerce websites. Paper presented at ACL 2017, System Demonstrations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August; pp. 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Oliveira, Jeferson, Danubia Bueno Espíndola, Regina Barwaldt, Luciano Maciel Ribeiro, and Marcelo Pias. 2019. Ibm watson application as faq assistant about moodle. Paper presented at the 2019 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 16–19 October; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci, David A. 2012. Introduction to “this is watson”. IBM Journal of Research and Development 56: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Rene, and Ralf Gerhardt. 2007. Investment mistakes of individual investors and the impact of financial advice. Paper presented at 20th Australasian Finance & Banking Conference, Sydney, Australia, 12–14 December. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, Ashok, Tory Anderson, Jordan Belknap, Brian Creeden, William Hancock, Mithun Kumble, Shanu Salunke, Bradley Sheneman, Abhinaya Shetty, and B Wilden. 2016. Using watson for constructing cognitive assistants. Advances in Cognitive Systems 4: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, WV, Keith C Brown, and Stephen E Jenks. 2020. The use and value of financial advice for retirement planning. The Journal of Retirement 7: 46–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, Matthew B. 2018. Alexa, siri, cortana, and more: An introduction to voice assistants. Medical Reference Services Quarterly 37: 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Marie-Claire, Richard Churchill, Stephen Cox, and Dan Smith. 2007. Analysis of user interaction with service oriented chatbot systems. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. New York: Springer, pp. 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, John E, III, and Steve Hamm. 2013. Smart Machines: IBM’s Watson and the Era of Cognitive Computing. Columbia: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Chih-Wei, Yau-Shian Wang, Tsung-Yuan Hsu, Kuan-Yu Chen, Hung-yi Lee, and Lin-shan Lee. 2018. Scalable sentiment for sequence-to-sequence chatbot response with performance analysis. Paper presented at 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Calgary, AB, Canada, 15–20 April; pp. 6164–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lui, Alison, and George William Lamb. 2018. Artificial intelligence and augmented intelligence collaboration: regaining trust and confidence in the financial sector. Information & Communications Technology Law 27: 267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz, Harry. 1952. Portfolio selection. The Journal of Finance 7: 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Alistair, Jama Nateqi, Stefanie Gruarin, Nicolas Munsch, Isselmou Abdarahmane, Marc Zobel, and Bernhard Knapp. 2020. An artificial intelligence-based first-line defence against covid-19: Digitally screening citizens for risks via a chatbot. Scientific Reports 10: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mausser, Helmut, and Oleksandr Romanko. 2014. Computing equal risk contribution portfolios. IBM Journal of Research and Development 58: 5:1–5:12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memeti, Suejb, and Sabri Pllana. 2018. Papa: A parallel programming assistant powered by ibm watson cognitive computing technology. Journal of computational science 26: 275–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, Adam S, Liliana Laranjo, and A Baki Kocaballi. 2020. Chatbots in the fight against the covid-19 pandemic. NPJ Digital Medicine 3: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montmarquette, Claude, and Nathalie Viennot-Briot. 2019. The gamma factors and the value of financial advice. Annals of Economics and Finance 20: 387–411. [Google Scholar]

- Murtaza, Syed Shariyar, Paris Lak, Ayse Bener, and Armen Pischdotchian. 2016. How to effectively train ibm watson: Classroom experience. Paper presented at 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January; pp. 1663–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nuruzzaman, Mohammad, and Omar Khadeer Hussain. 2018. A survey on chatbot implementation in customer service industry through deep neural networks. Paper presented at 2018 IEEE 15th International Conference on e-Business Engineering, Xi’An, China, 12–14 October; pp. 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, Takuma, and Sanae Shoda. 2018. Ai-based chatbot service for financial industry. Fujitsu Scientific and Technical Journal 54: 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Przegalinska, Aleksandra, Leon Ciechanowski, Anna Stroz, Peter Gloor, and Grzegorz Mazurek. 2019. In bot we trust: A new methodology of chatbot performance measures. Business Horizons 62: 785–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranoliya, Bhavika R, Nidhi Raghuwanshi, and Sanjay Singh. 2017. Chatbot for university related faqs. Paper presented at 2017 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics, Udupi, India, 13–16 September; pp. 1525–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rese, Alexandra, Lena Ganster, and Daniel Baier. 2020. Chatbots in retailers’ customer communication: How to measure their acceptance? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 56: 102176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanko, Oleksandr, and Helmut Mausser. 2016. Robust scenario-based value-at-risk optimization. Annals of Operations Research 237: 203–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanko, Oleksandr, and Helmut Mausser. 2017. Applications of conic linear optimization in financial engineering. In Advances and Trends in Optimization with Engineering Applications. Edited by Tamas Terlaky, Miguel F. Anjos and Shabbir Ahmed. Philadelphia: SIAM, Chapter 12. pp. 149–60. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Ming-Hsiang, Chung-Hsien Wu, Kun-Yi Huang, Qian-Bei Hong, and Hsin-Min Wang. 2017. A chatbot using lstm-based multi-layer embedding for elderly care. Paper presented at 2017 International Conference on Orange Technologies, Singapore, 8–10 December; pp. 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Richard S. 2009. The anatomy of alice. In Parsing the Turing Test. New York: Springer, pp. 181–210. [Google Scholar]

- Weizenbaum, Joseph. 1966. Eliza—A computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Communications of the ACM 9: 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Anbang, Zhe Liu, Yufan Guo, Vibha Sinha, and Rama Akkiraju. 2017. A new chatbot for customer service on social media. Paper presented at Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May; pp. 3506–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Li, Jianfeng Gao, Di Li, and Heung-Yeung Shum. 2020. The design and implementation of xiaoice, an empathetic social chatbot. Computational Linguistics 46: 53–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).