1. Introduction

Over the last three decades, many countries, including Australia, have been facing a swift growth in household debt (

Meng et al. 2013). Since 2002, the mean value of household debt in Australia increased by 87 per cent, whereas the mean value of assets grew only by 42 per cent (

Wilkins 2016, p. 10). Moreover,

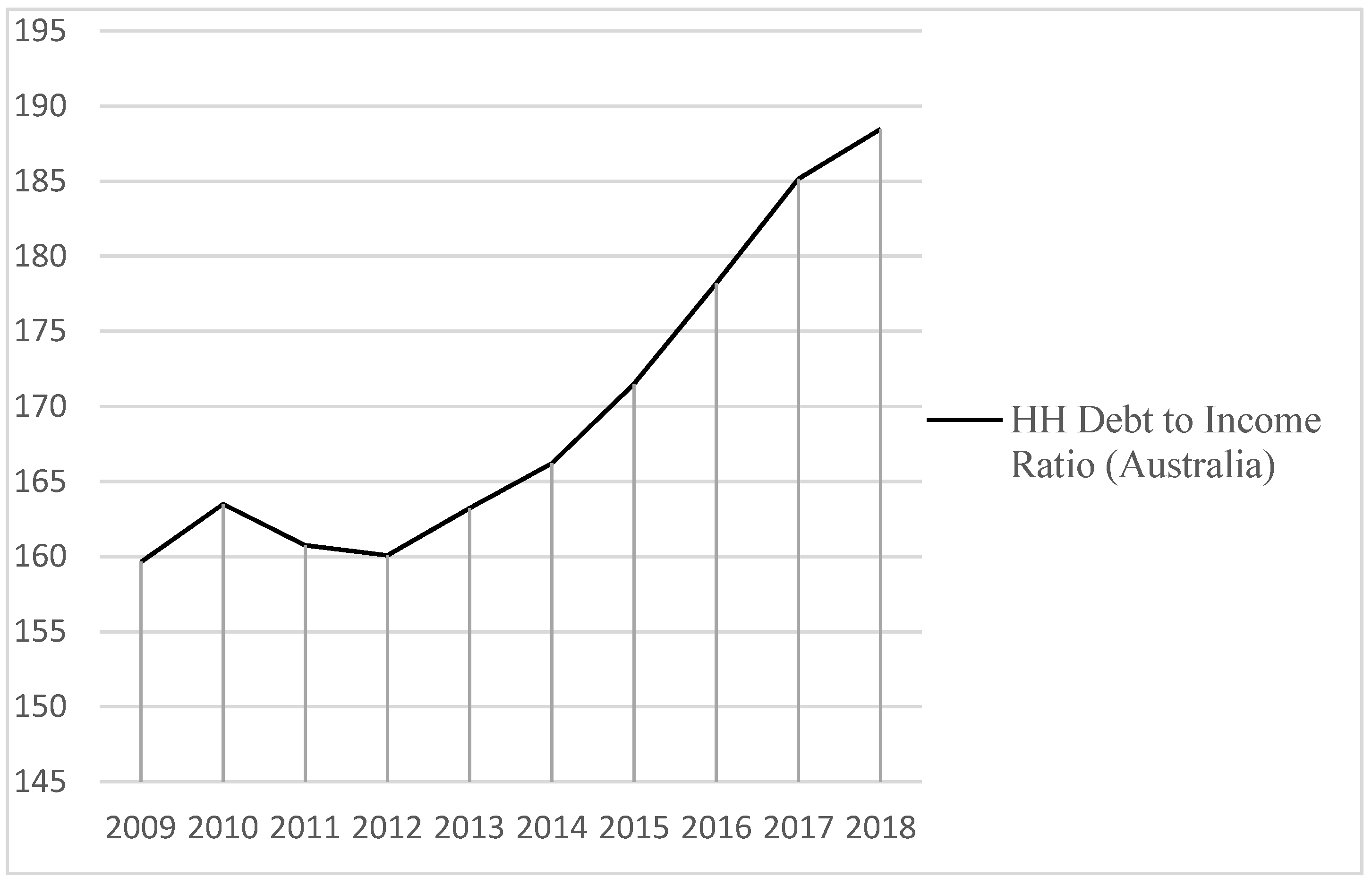

Figure 1 shows the Australian household debt to income ratio from 2009 to 2018, depicting that the household debt-to-income ratio was 159 in 2009 and surged to 188 in 2018. Within these ten years, a slight decline was noted from 2010 to 2012. However, the ratio increased by an increasing rate from 2012 to 2017. These statistics have sounded the tocsin thus loudly that a report from the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (

ASIC 2017, p. 5) noted, “the ratio of household debt to household income is at a record high”. Research conveys that debt taken beyond means can cause health problems such as anxiety and depression, mental health issues, drug addiction, heart problems, or migraine headaches (

Berger et al. 2016;

Jarl et al. 2015;

Meltzer et al. 2010;

Richardson et al. 2013;

Sweet et al. 2013;

Turunen and Hiilamo 2014). Given the negative consequences of rising household debt, it is important to identify factors relevant to the reduced debt-taking behaviour of Australians.

Recent research highlights the importance of improving financial wellbeing (

Tahir et al. 2021). Financial wellbeing refers to an individual’s perception of the personal financial situation (

Brüggen et al. 2017). The emerging concept of financial wellbeing is a part of the financial planning subject that is gaining researchers’ attention globally (

Altfest 2004;

Liao and Xiao 2014;

McKeown et al. 2014). The empirical research of

Garðarsdóttir and Dittmar (

2012) in Finland analysed the association between materialism and financial wellbeing. They concluded that those with a more materialistic mindset have more financial worries, worse money-management skills, a greater tendency to compulsive buying, and more debt. Similarly, the empirical findings of

Donnelly et al. (

2012) show that a better perception of personal financial situation leads to an increase in savings and reduction in debt burden. In addition, they find an association between better financial decision-making ability and improved financial wellbeing status. As debt taking is a part of households’ financial decisions, extant research finds that improving financial knowledge is associated with reduced credit card debt-taking behaviour (

Tahir et al. 2020). However, the research of

Tahir et al. (

2020) is limited to a cross-sectional survey. In this study, we expand on the findings of

Tahir et al. (

2020) by using panel data and address the following research question:

To what extent does financial wellbeing relate to reduced debt-taking behaviour?

To meet the objective of this research, we use the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. The findings show that improving households’ perception of their personal financial situation can improve their financial decisions, including the decision to take on debt. The research has policy implications, suggesting that improving financial wellbeing exerts both the short-run and long-run benefits.

The next section of this paper reviews relevant prior studies followed by an explanation of the dataset and method of data analysis. Next, we present empirical results, discuss and conclude the results, and state the directions for future research.

3. Data

According to

Campbell (

2006), if a researcher wishes to use a dataset to analyse household finance empirically, it should have at least five features. These five features are: collecting the detail of household wealth and categorising it into sub-parts, these sub-parts must represent an asset classification, the dataset must represent a true sample of the whole population, accuracy-level must be high, and the data must be collected repeatedly on regular intervals (

Wilkins 2016).

Until 2000, there was no dataset in Australia, which could represent such characteristics (

Wilkins 2016). Since 2001, Australia has been equipped with a rich set of data called the HILDA survey. This dataset has met the requirements of

Campbell (

2006) as quoted by

Wilkins (

2016, p. 6): “It is, by design, representative of the Australian population; it produces a comprehensive measure of each household’s wealth, in total and by component; and household wealth data has been collected from the same households every four years since 2002.”

HILDA is a household panel survey (

Richardson 2013). The survey of each year is called a “wave”. HILDA has a high response rate—66 per cent in the first wave. Under HILDA, the same families are surveyed each year with a retention rate of 96.2 per cent in wave 18 (

Summerfield et al. 2019). The authorities collected data of wave 18 in 2018 and granted access in 2020. Wave 18 contains 17,434 persons interviewed from 9639 households across Australia. The HILDA user manual lists the number of persons who responded to each wave since its start (

Summerfield et al. 2019, pp. 6–7).

Researchers have been using this rich dataset for empirical analyses since its start in 2001 (

Wilkins 2016;

Wooden et al. 2002;

Wooden and Watson 2007). HILDA has been able to produce hundreds of nationally representative research works (

Richardson 2013). As HILDA is not limited to a specific topic, it has been able to produce multi-disciplinary analyses. Similar to the other disciplines, it has contributed to the knowledge of social sciences as well. The literature of personal and household finance has also been able to obtain a sheer knowledge through the empirical analyses of HILDA survey (several examples include:

Ambrey and Fleming (

2014),

Brown and Gray (

2016),

Cobb-Clark and Ribar (

2012),

Cobb-Clark et al. (

2016),

Gong and Kendig (

2018),

Headey and Wooden (

2004),

Headey (

2008),

Kristoffersen (

2017),

West and Worthington (

2019),

Wilkins and Wooden (

2009), and many others). Thus, the current study also claims to contribute to the knowledge of behavioural, personal, and household finance by employing data from the HILDA survey.

HILDA has a special wealth module, which collects personal and household wealth data every four years since 2002 (

Wilkins 2016). This special wealth module asks people if they currently do or do not hold different loans, including bank loans, investment loans, car loans, student loans, and other types of loans.

Table 1 presents the loan types and their items in wave 18 only.

Next, all the debt types are combined to form one variable.

Table 2 shows that all those respondents who hold at least one type of loan are combined into one category of “yes”, whereas the other category “no” contains all the respondents who do not have any type of loan. Hence, debt-taking behaviour is a dichotomous dependent variable of the study, coded “0” for category “no” and “1” for category “yes”. Those who fall in the latter category has debt-taking behaviour.

HILDA added a personal loan survey in the wealth module in 2006. Currently, four waves contain responses on personal loans: wave 6, wave 10, wave 14, and wave 18. Responses to these four waves are merged to make it a panel dataset. In the next step, we clean and filter the panel dataset and retain only those respondents who responded to our key variables in the four waves. This step omits the missing responses and creates a balanced panel for empirical analysis.

Table 3 displays the summary statistics of the balanced panel.

Financial wellbeing is measured using two subjective items.

Brown and Gray (

2016) have used these items to measure financial wellbeing. The first item relates to subjective prosperity, that is, given your current needs and financial responsibilities, would you say that you and your family are? There were six options available to the respondent, from prosperous to poor. To make this item consistent with other variables of this study, we reverse the scale of this item from poor to prosperous. The second item relates to financial satisfaction, that is, show your satisfaction level with your current financial situation? There were 11 options available to respondents from “0” for totally dissatisfied to “10” for totally satisfied.

Because subjective prosperity and financial satisfaction were measured on different scales, we standardised and combined the financial wellbeing items using the z-score methodology (

Kesavayuth et al. 2018,

2020). In the empirical analysis of this paper, the standardised financial wellbeing scores will be used.

4. Methodology

Two types of models that are usually generated in a panel data analysis are the random-effects model and the fixed-effects model. “Fixed-effects models treat the effect size parameters as fixed but unknown constants to be estimated and usually (but not necessarily) are used in conjunction with assumptions about the homogeneity of effect parameters” (

Hedges and Vevea 1998, p. 486). Furthermore, fixed-effects models exclude those respondents from the statistical analysis who do not change their response over time. In addition, the structure of the fixed-effects model allows the observed predictors to correlate with υ. Conversely, “random-effects models treat the effect size parameters as if they were a random sample from a population of effect parameters and estimate hyperparameters (usually just the mean and variance) describing this population of effect parameters” (

Hedges and Vevea 1998, p. 486). Moreover, unlike fixed-effects models, random-effects models include all the respondents in the statistical analysis whether they change their responses over time or not. In addition, the structure of the random-effects model does not allow the observed predictors to correlate with υ.

Both models are widely used in panel data analyses. However, the choice between both is based on the researchers’ assumptions and the structure of their specific model. Researchers often use the Hausman test to choose between both models (

Hausman 1978). According to

Bell et al. (

2019), the Hausman test is not a test to choose between both models. Rather, it is only a test of whether the within and between effects are different. In many cases, the Hausman test allows using fixed-effects estimates instead of random-effects estimates (

Bell et al. 2019). However, the problem occurs when the within variation is too small, which may invalidate the asymptotical normality assumption of the fixed-effects estimates (

Hahn et al. 2011). As the fixed-effects model drops the observations where the person does not change the response across the waves, the sample size dramatically diminishes and may provide flawed results.

As the fixed-effects model drops a large number of responses reflecting a small sample size, we choose to use the random-effects model in further empirical analyses. In addition, the recent literature does not support the recommendations of the Hausman test to choose between the fixed-effects and random-effects model (

Bell et al. 2019). Instead, data with a small “within variation” are highly recommended to employ the random-effects model (

Hahn et al. 2011;

Kesavayuth et al. 2020).

Hunter and Schmidt (

2000) also prefer the random-effects model over the fixed-effects model in social science research. Therefore, a random-effects model is a better choice in the case of this paper.

5. Estimation Results

For the purpose of showing the within and between components of financial wellbeing and the transition probabilities of financial wellbeing, the financial wellbeing variable is transformed into a dichotomous variable, coded zero if the mean value is below zero (representing relatively lower levels of financial wellbeing) and coded one if the mean value is above zero (representing relatively higher levels of financial wellbeing).

Table 4 conveys the within and between components of two main variables, debt-taking behaviour and financial wellbeing. The overall statistics summarise the person-years results. Out of 20,452 person-years, 15,674 did not have debt, while 4778 had debt. The “between” statistics summarise the data in terms of the respondents, showing that 4869 respondents never had debt, while 2445 had debt, a total of 7314 having either. Next, the “within” per cent shows the fraction of the time a respondent had debt. Conditional on a respondent ever having a “0” (not taking on debt) response, 80.48 per cent of their observations have a “0” response. Likewise, conditional on a respondent ever having a “1” (taking on debt) response, 48.85 per cent of their observations have a “1” response. The total within per cent of 69.91 is then the normalised between the weighted average of the within per cent ((4869 × 80.48) + (2445 × 48.85) ÷ 7314).

Table 5 below depicts the transition probabilities of respondents from one period to the next period. It shows that 87.51 per cent of respondents with a “0” response in a given period have a “0” response in the next period as well. Similarly, 51.85 per cent of respondents with a “1” response in a given period have a “1” response in the next period as well. Further,

Table 5 indicates that 12.49 per cent of respondents with a “0” response in a given period have a “1” response in the next period, while 48.15 per cent of respondents with a “1” response in a given period have a “0” response in the next period.

Regarding the statistics of financial wellbeing,

Table 6 shows a transition of 41.83 per cent of respondents from a lower level of financial wellbeing in a given period towards a relatively higher level of financial wellbeing in the next period, as compared to 17.12 per cent of respondents transitioned from a higher level of financial wellbeing in a given period towards a relatively lower level of financial wellbeing in the next period. This trend shows a relatively greater percentage of respondents who transitioned towards higher levels of financial wellbeing.

Table 7 displays the results of the two-panel binary logistic regression models. In the first model, the main independent variable, financial wellbeing, is regressed on debt-taking behaviour. The statistically significant AME with a negative sign implies that financial wellbeing has a significant negative association with debt-taking behaviour.

The second model of

Table 7 regresses the one-year lagged financial wellbeing on debt-taking behaviour of t time period. The results indicate that the one-year lagged financial wellbeing has a significant negative association with debt-taking behaviour.

“Rho” is the per cent of variation that is explained by the individual-specific effects. A “rho” value close to “1” is perceived better for the overall model, while “rho” equal to or near “0” indicates that the random-effects regression model is not different from a pooled regression model (

Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal 2008;

Tyack and Ščasný 2020). Both the models of

Table 7 have a “rho” of more than 0.30, implying that these models are better than a pooled regression model (

Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal 2008). A pooled regression model is a model where the dataset is not declared a panel dataset but run as a simple regression model.

In the next phase of analysis,

Table 8 controls the one-year lagged debt-taking behaviour to see if the results of

Table 7 are consistent. As

Table 8 presents that “rho” is near to zero in both the models, it implies using a pooled regression model instead of a panel regression model. Thus, the results are generated without declaring the dataset as a panel model. In both the models of

Table 8, financial wellbeing and the one-year lagged financial wellbeing are negatively significant, respectively. The results imply that financial wellbeing of t − 1 and t time period is significantly and negatively associated with debt-taking behaviour of t time period, after controlling for the socio-demographic factors and the one-year lagged debt-taking behaviour. The findings meet our objective by demonstrating that improved financial wellbeing reduces the debt-taking behaviour of Australians. Furthermore, the interpretation of the AMEs in

Table 8 can be read as: the probability of taking on debt decreases by 4.7% and 2.9% with a one standard deviation positive change in financial wellbeing and one-year lagged financial wellbeing, respectively.

Robustness Checks

For the purpose of checking robustness of the empirical findings of this paper, we chose credit card debt taking behaviour as the dependent variable as used by

Tahir et al. (

2020). Credit card debt is regarded as one of the problematic types of household debt (

Tahir et al. 2020). Furthermore, we employ an unbalanced data from wave 11 to 17 (seven waves) to see if a change in respondents affect the relationship between financial wellbeing and debt-taking behaviour.

Table A1 in the appendix section shows the summary statistics, whereas

Table A2 displays the results of the panel analysis. As can be seen that financial wellbeing is still negatively associated with debt-taking behaviour, we conclude that our findings are robust.

6. Discussion

A review of the literature highlighted that financial wellbeing is a strong predictor of overall wellbeing (

Netemeyer et al. 2018) and a relatively stronger indicator of developed money-management skills, which improve the quality of household financial decisions (

Vlaev and Elliott 2014). Given these findings of prior research about financial wellbeing, the aim of this paper was to explore whether improved financial wellbeing has an association with decreased household debt-taking behaviour. We analysed this association using panel analysis of HILDA survey. The empirical results indicated a strong negative relationship between financial wellbeing and debt-taking behaviour. Our robustness analysis also confirmed our main empirical findings. The findings are an extension to the prior research, which posits that higher financial wellbeing levels are associated with lower financial stress (

Choi et al. 2020), positive overall wellbeing (

Netemeyer et al. 2018), improved quality of life and mental wellbeing (

Blanchflower and Oswald 2004), improved health wellbeing (

Bridges and Disney 2010), risk-tolerance (

Joo and Grable 2004), and positive financial behaviour (

Brüggen et al. 2017;

Xue et al. 2019).

Our results are comparable to prior relevant research. The empirical results of

Ajzerle et al. (

2013) showed a positive association between financial capability and debt management.

Robb (

2011) claimed that people with high financial knowledge exhibit relatively responsible credit card use. Similarly,

Brown et al. (

2016) found that young consumers with high financial knowledge had decreased debt dependence.

Brown and Gray (

2016) concluded a negative association of subjective prosperity and financial satisfaction with debt-levels. In an analysis of student data,

Solis and Ferguson (

2017) found an association between student loans and financial dissatisfaction. Unlike these prior studies, this paper analysed behaviour of households around debt-taking and finds that those with higher levels of financial wellbeing have lower probabilities of taking on debt.

7. Conclusions, Implications, and Future Research Directions

The unique contribution of this paper is that it adds to our knowledge that a household’s positive perception of his/her personal financial situation can go top of the other factors to have a relevance with the reduced propensity towards undertaking debt. The finding is worthwhile to consider in the Australian context, where household debt is at a record high (

ASIC 2017). We suggest policymakers to consider improving Australian households’ financial wellbeing. Financial planners and advisors can play a vital role to help households improve their financial wellbeing and financial decisions. As households seek advice from financial planners regarding their financial planning (such as retirement planning and financial contracts commitments), financial planners can assess households’ ability to conduct financial tasks as it has a direct connection with improved financial wellbeing (

Tahir et al. 2021). Financial planners should encourage their clients to employ the ability of self-control and create proper financial plans. For this purpose, the managing organisations and associations in the financial services industry should organise practical workshops and seminars to spread awareness. The government can also play a role by sponsoring these workshops and seminars to provide financial support in managing these activities. These efforts will serve the purpose of reducing the propensity of households towards undertaking debt (

Brown and Gray 2016;

Haq et al. 2018;

Kolios 2020).

The findings suggest that the policies of financial institutions should be designed, keeping in view the interest of households and under the surveillance of a dedicated department of the state government. Consumer-related policies should be regularly monitored and include flexible terms according to the given financial condition of households. It is one of the responsibilities of the government to ensure that the policies of financial institutions are in the best interest of the public.

Despite several contributions and implications, this paper has limitations, which researchers may wish to address in the future. In this context, the first limitation relates to the items used to measure the constructs of this research. The objective measures of financial wellbeing could produce different findings. Furthermore, a different measure of debt-taking behaviour could produce a different outcome. In addition, other factors related to personal finance, such as financial capability, financial literacy, financial risk-taking attitude etc., can also be relevant to debt-taking behaviour. A panel analysis using these other factors can be helpful to draw interesting conclusions. Moreover, our findings do not show a causal relationship between financial wellbeing and debt-taking behaviour, i-e: increase in financial wellbeing reduces debt-taking behaviour. Instead, we only interpret an association between improved financial wellbeing and reduced debt-taking behaviour. We suggest future research to delve deeper into these concepts and find the causality between financial wellbeing and debt-taking behaviour using relevant theoretical and empirical support. Finally, we acknowledge that our data were collected before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we recommend future research to replicate this research in post-covid settings to see if similar findings could be generated.