Firm Size Does Matter: New Evidence on the Determinants of Cash Holdings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

3. Variable Measurement and Research Design

3.1. Variable Measurements

3.2. Research Design

4. Data, Sample Selection, and Descriptive Statistics

4.1. Data and Sample Selection

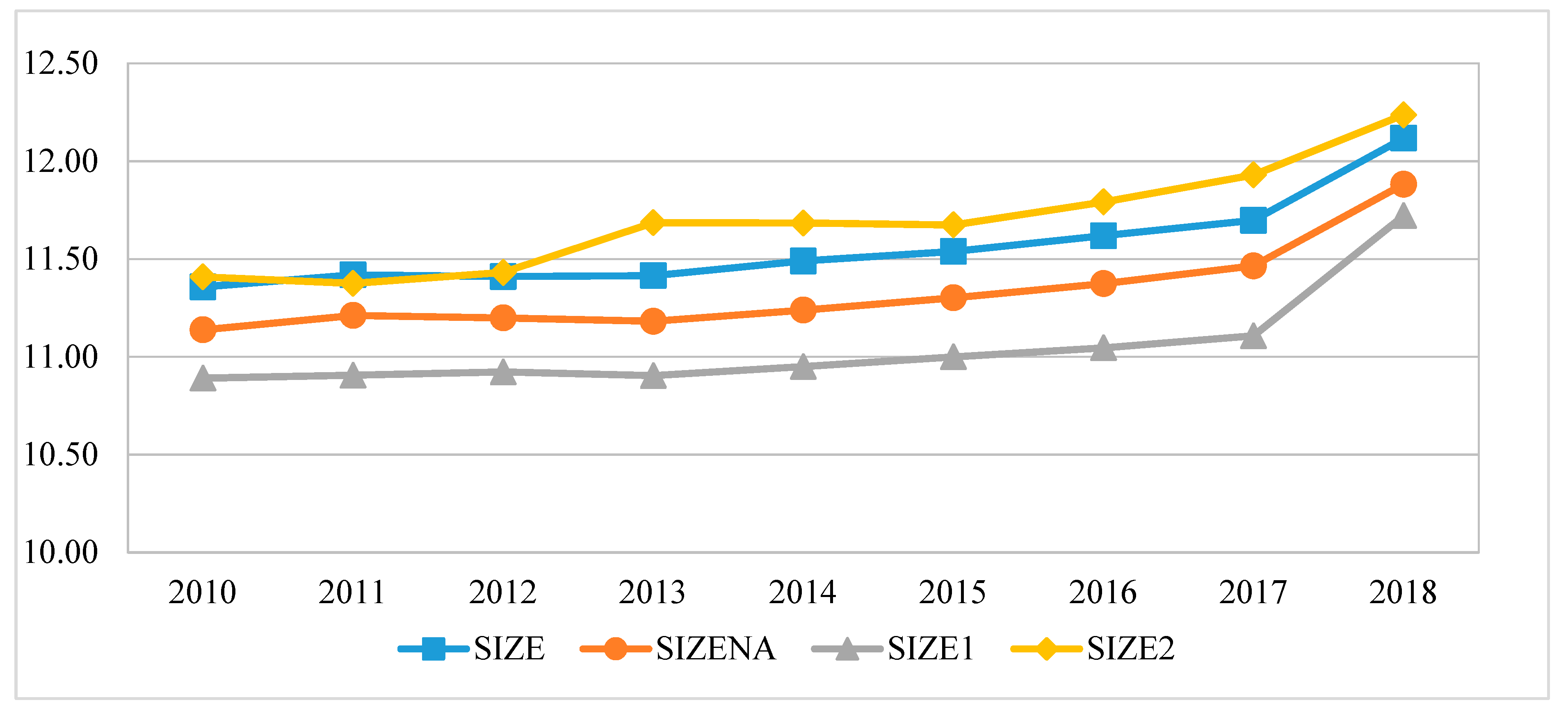

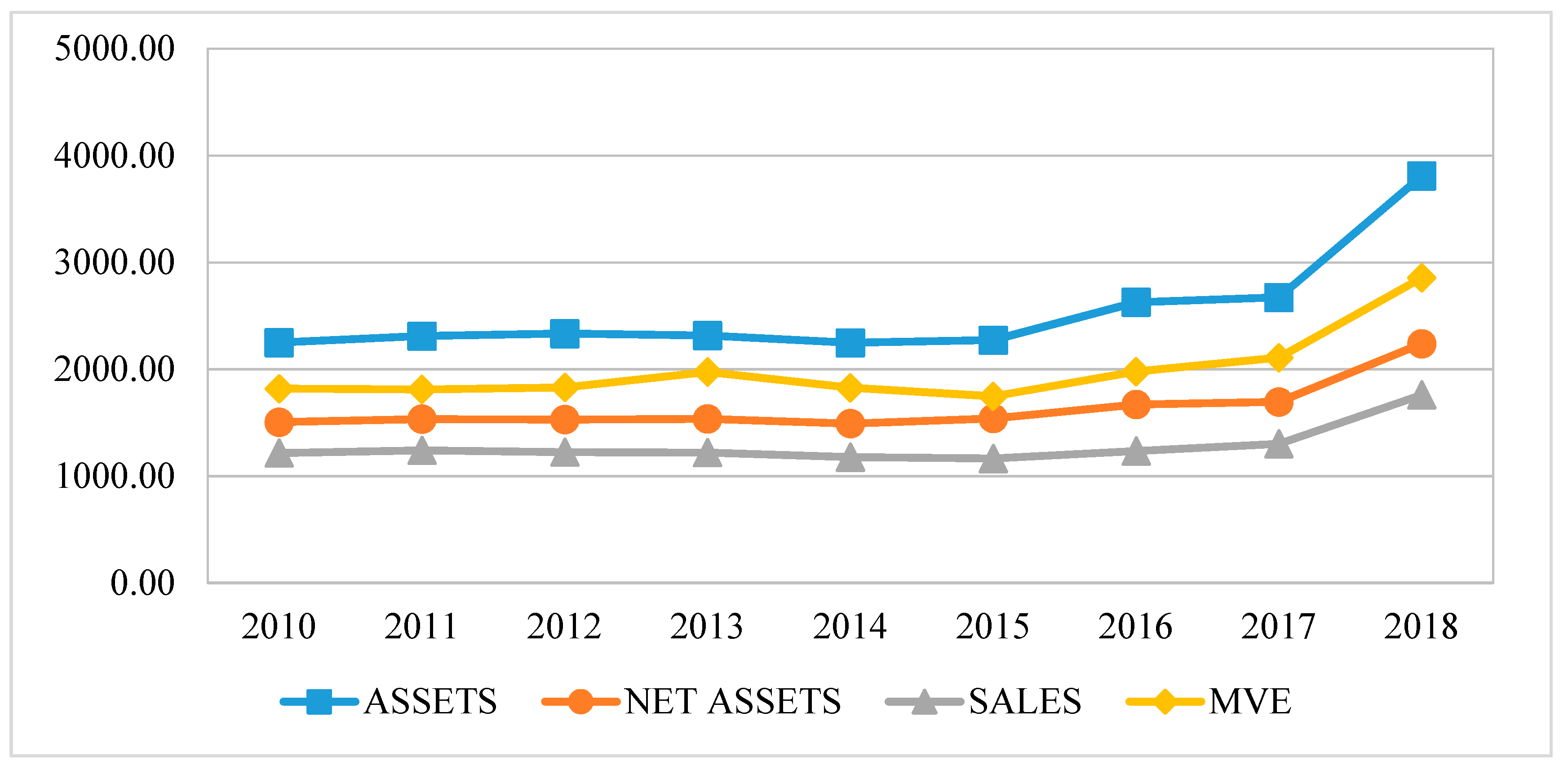

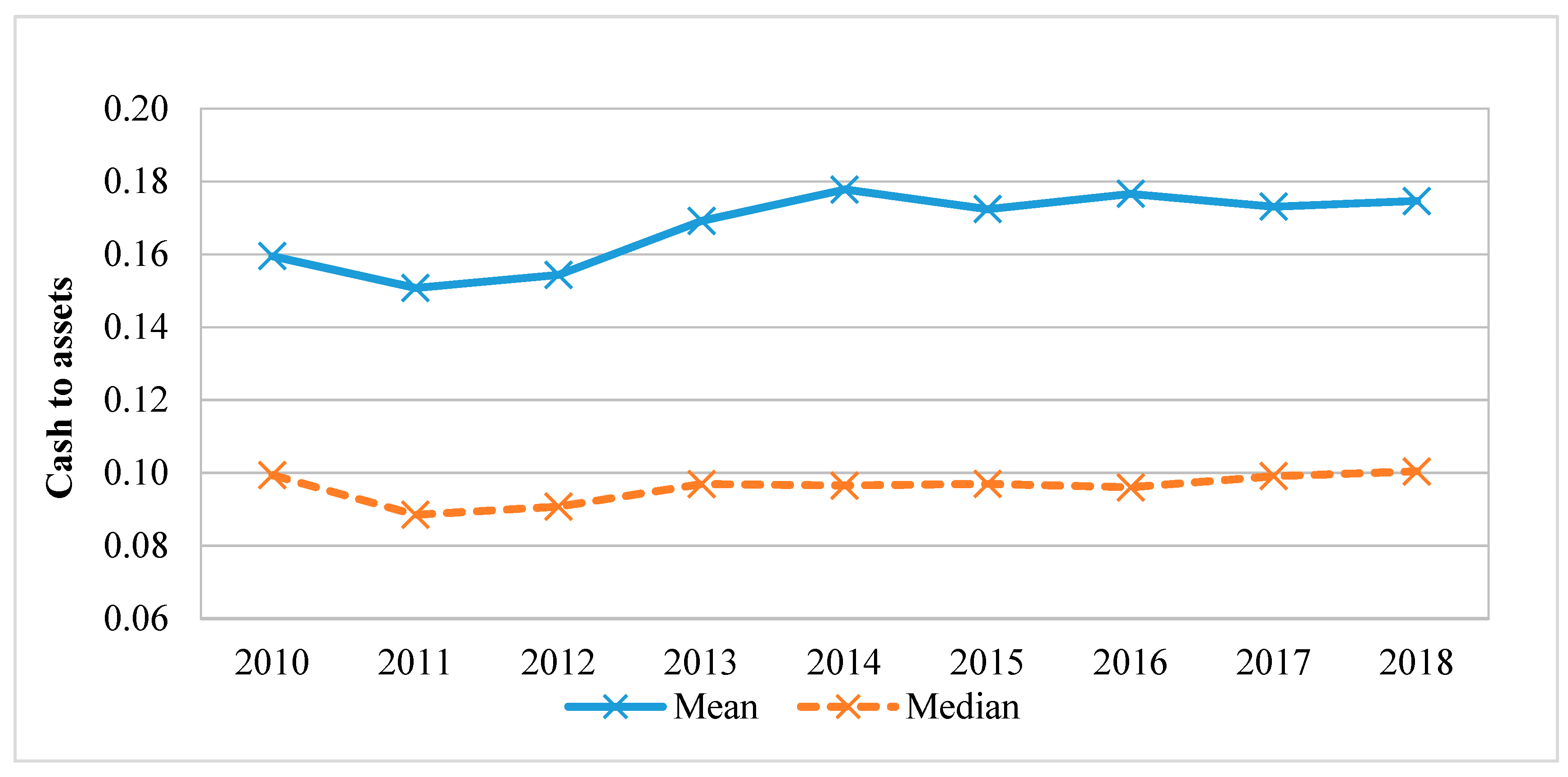

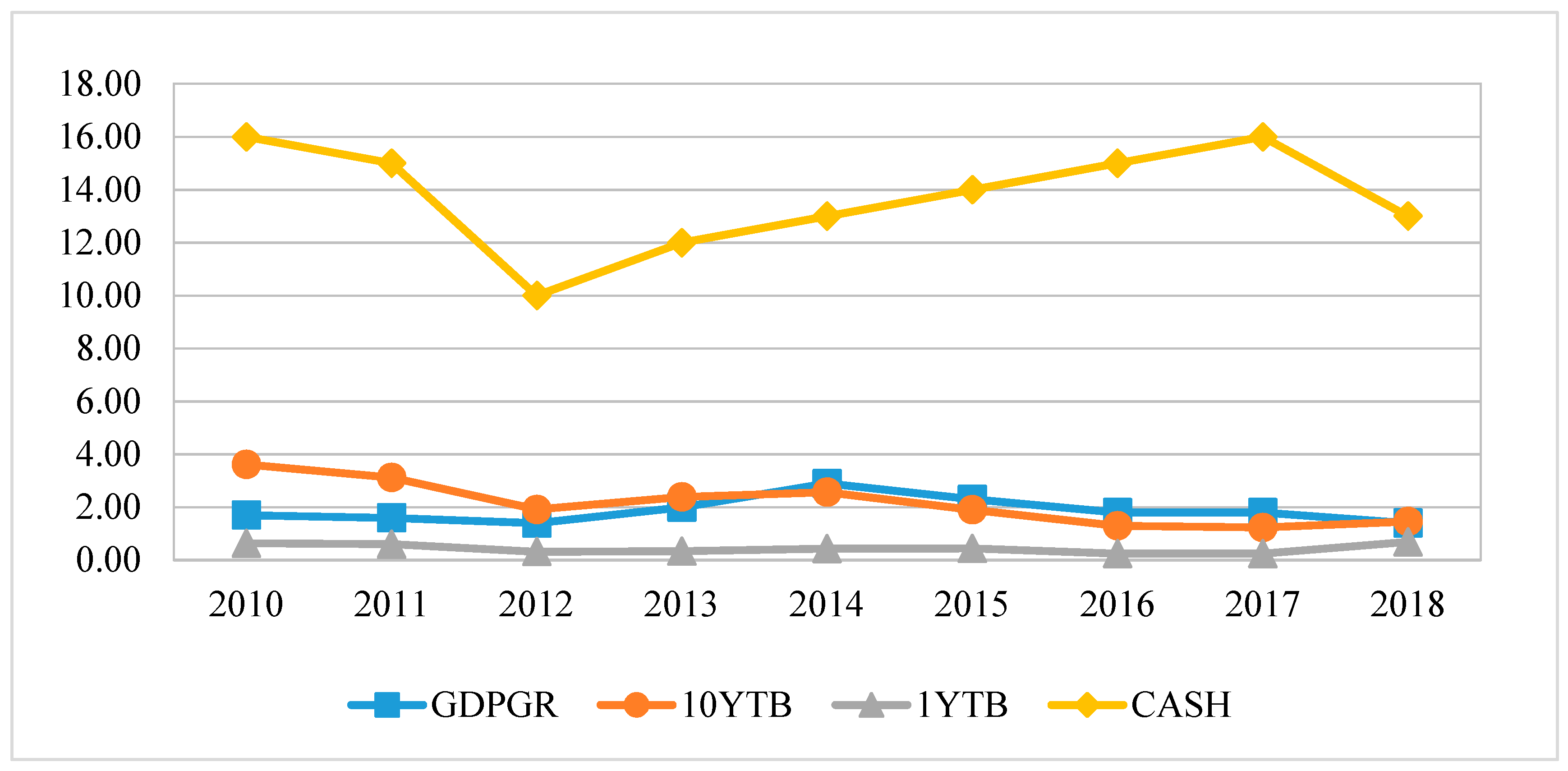

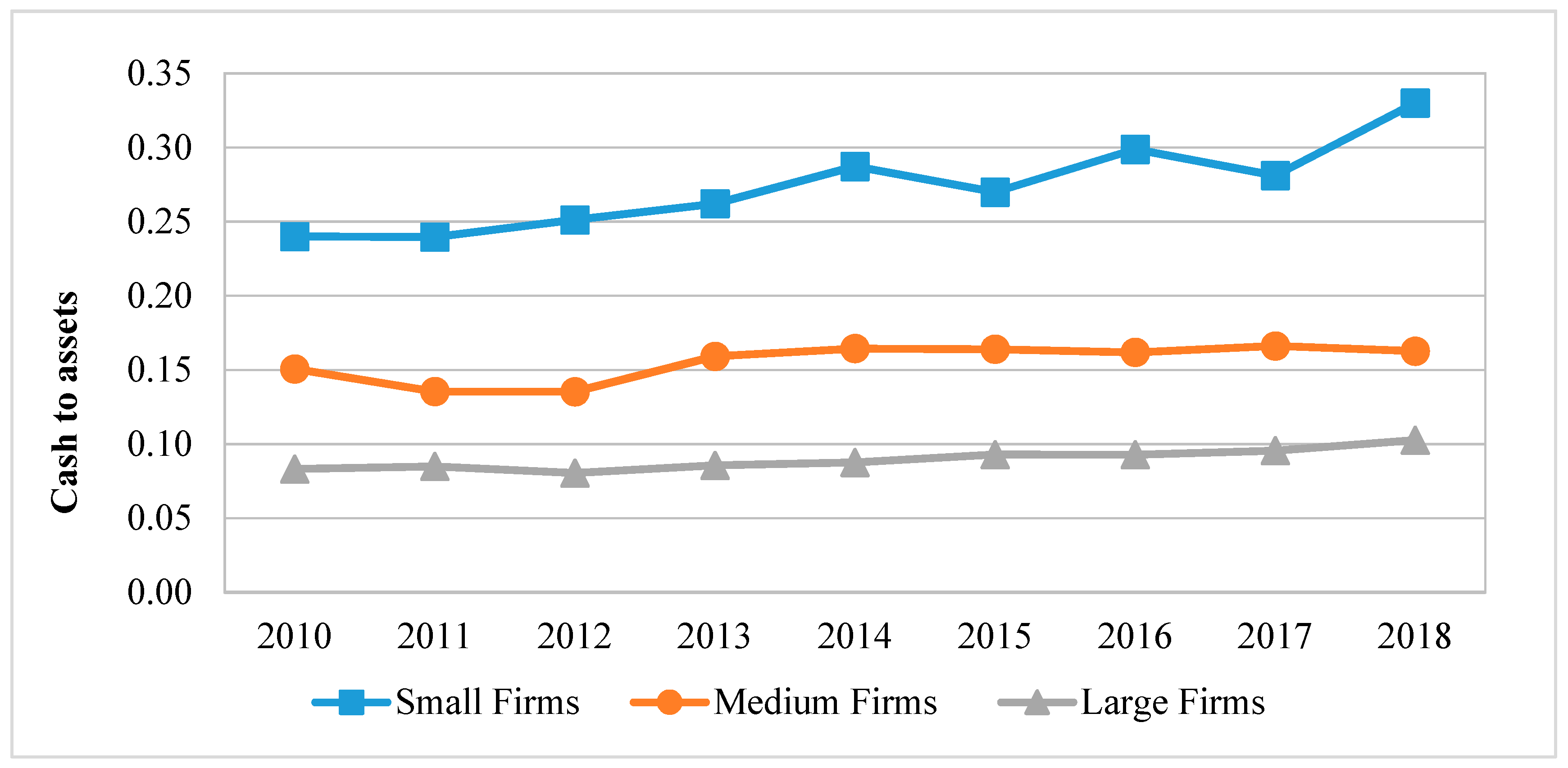

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

5. Main Results

5.1. Determinants of Cash Holdings

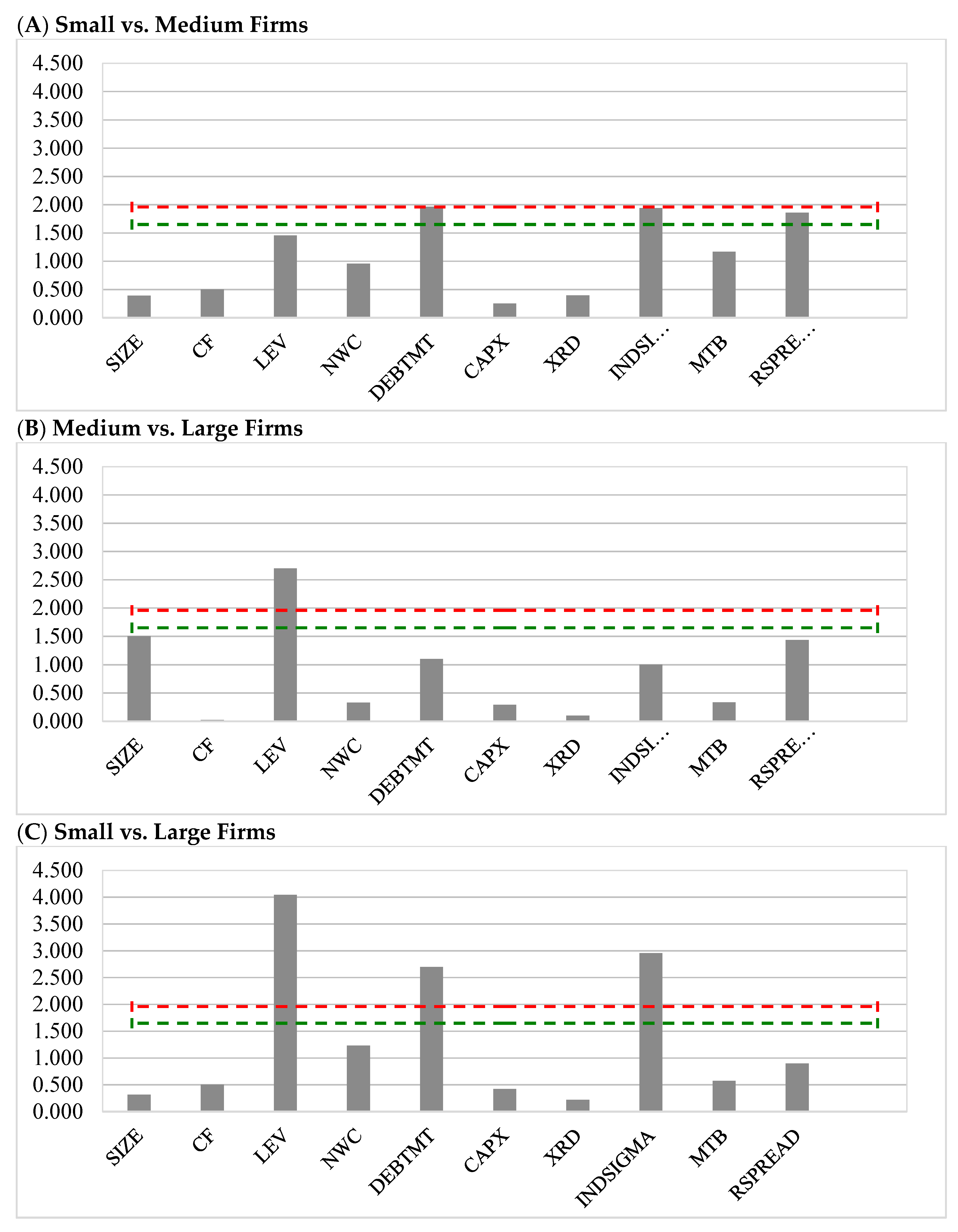

5.2. Small, Medium, and Large-Sized Firms

6. Additional Analyses

6.1. Ownership, Board Structure, and Cash Holdings

6.2. Cross-Sectional Tests

6.3. Two-Step System GMM Estimation

6.4. Analysis in Alternative Periods

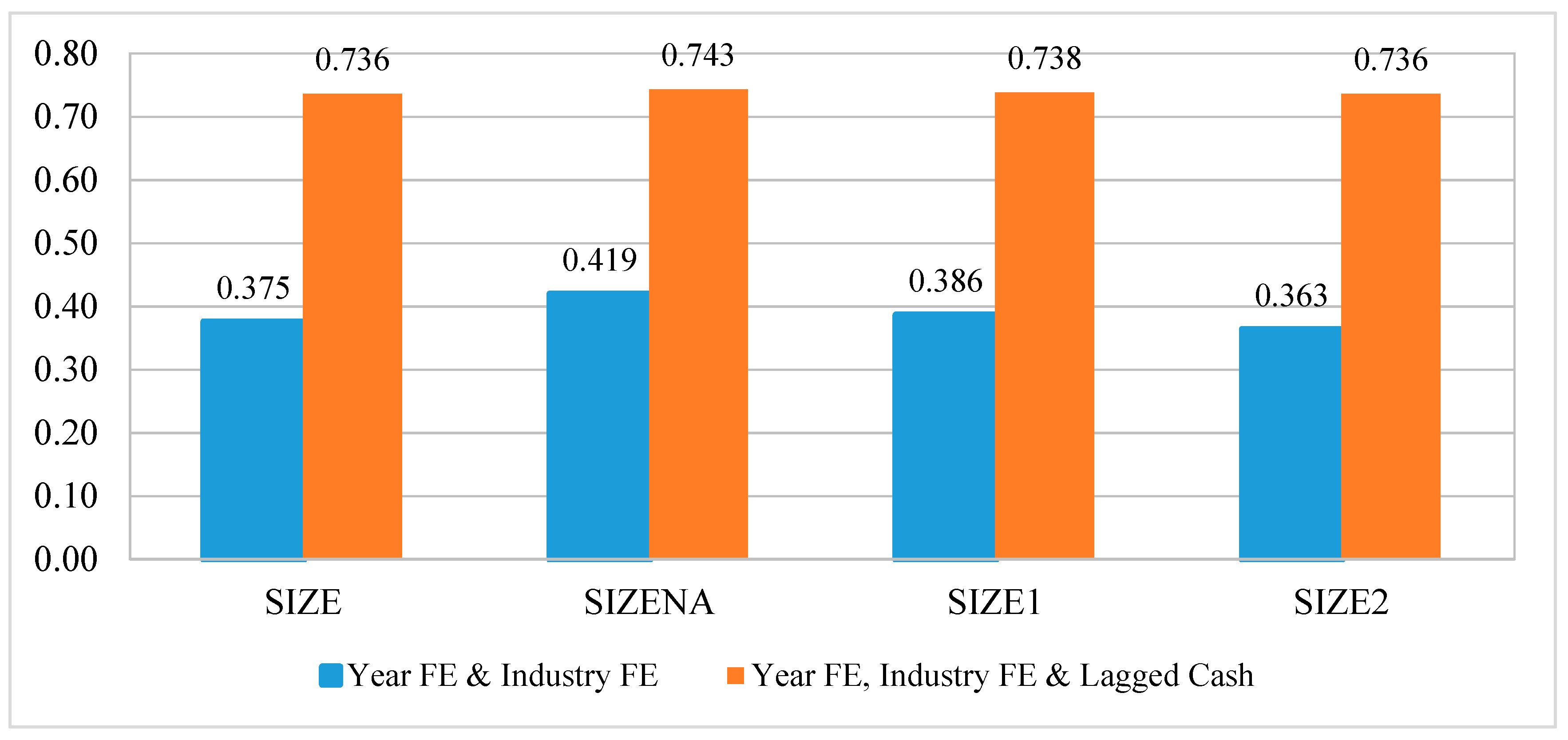

6.5. Different Firm Size Proxies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name | Definition |

|---|---|

| CASH | Cash and cash equivalents to total assets; |

| SIZE | Natural logarithm of total assets |

| CF | Cash flow (pre-tax profits + depreciation + amortization) scaled by total sales |

| LEV | Total debt (short-term debt + long-term debt) to total assets |

| NWC | Current assets−current liabilities−cash and cash equivalents to total assets |

| DEBTMT | Long-term debt to total liabilities |

| CAPEX | Change of fixed assets plus depreciation and amortization to total assets |

| XRD | Ratio of research and development expenses to sales |

| INDSIGMA | Mean of Σ(CF/total assets) for firms in the same industry |

| MTB | Total assets−common shareholders equity-market capitalization fiscal period end scaled by total assets |

| RSPREAD | Gross operating profit/assets−interest rate 1-Yr T-Bills |

| INT | Interest rate 1-Yr T-Bills |

| GDPGR | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) percentage change on previous year |

| MAN | Total percentage of equity ownership by company directors |

| BOARDNB | Number of the members of the board |

| CEO_COB | Dummy variable which takes a value of 1 if the positions of the CEO and the COB are held by the same individual and 0 otherwise |

| L.CASH | Lagged cash and cash equivalents to total assets |

| SIZEDUMMY | Binary variable, which takes the value one (zero) for firms where SIZE is above (below) the sample’s median |

| SMALLvsLARGE | Binary variable, which takes the value one for large firms (SIZE ≥ p75) and zero for small firms (SIZE ≤ p25) |

| MEDIUMvsLARGE | Binary variable, which takes the value one for large firms (SIZE ≥ p75) and zero for medium firms (p25 < SIZE < p75) |

| HHI | Herfindahl-Hirschman Index computed using firm sales for each three-digit industry codes for every year in the sample. First, the sales ratio is computed by dividing sales of each firm to the total sales in the 3-digit code industry. Second, HHI is computed as the sum of the squares of the ratio for all firms in the same industry |

| ALTMAN | Altman’s Z-Score provided by the Amadeus database |

| AGE | Years since the date of foundation |

| SIZENA | Natural logarithm of total assets minus cash and cash equivalents |

| SIZE1 | Natural logarithm of total firm sales |

| SIZE2 | Natural logarithm of market value of equity |

Appendix B

| Panel A: Summary Statistics | ||||||||

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | N | ||||

| ASSETS (mil. £) | 2477.459 | 14,505.045 | 9.990 | 332,160.992 | 6629 | |||

| NET_ASSETS (mil. £) | 1609.543 | 6056.685 | 0.011 | 45,904.000 | 6629 | |||

| SALES (mil. £) | 1257.501 | 4294.122 | 0.012 | 30,758.000 | 6629 | |||

| MVE (mil. £) | 1957.864 | 8128.579 | 0.000 | 115,094.496 | 6024 | |||

| SIZE | 11.540 | 2.440 | 4.892 | 17.645 | 6629 | |||

| SIZENA | 11.309 | 2.583 | 3.497 | 17.582 | 6629 | |||

| SIZE1 | 11.018 | 2.896 | 2.485 | 17.242 | 6629 | |||

| SIZE2 | 11.681 | 2.399 | 6.732 | 17.566 | 6024 | |||

| Panel B: Correlation | ||||||||

| V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V8 | |

| V1: ASSETS | 1 | 0.993 *** | 0.917 *** | 0.914 *** | 1.000 *** | 0.993 *** | 0.917 *** | 0.915 *** |

| V2: NET_ASSETS | 0.794 *** | 1 | 0.921 *** | 0.893 *** | 0.993 *** | 1.000 *** | 0.921 *** | 0.893 *** |

| V3: SALES | 0.756 *** | 0.920 *** | 1 | 0.845 *** | 0.917 *** | 0.921 *** | 1.000 *** | 0.845 *** |

| V4: MVE | 0.833 *** | 0.866 *** | 0.818 *** | 1 | 0.914 *** | 0.893 *** | 0.845 *** | 1.000 *** |

| V5: SIZE | 0.367 *** | 0.535 *** | 0.551 *** | 0.468 *** | 1 | 0.993 *** | 0.917 *** | 0.915 *** |

| V6: SIZENA | 0.357 *** | 0.521 *** | 0.537 *** | 0.454 *** | 0.991 *** | 1 | 0.921 *** | 0.893 *** |

| V7: SIZE1 | 0.312 *** | 0.453 *** | 0.503 *** | 0.401 *** | 0.886 *** | 0.893 *** | 1 | 0.845 *** |

| V8: SIZE2 | 0.361 *** | 0.518 *** | 0.538 *** | 0.479 *** | 0.919 *** | 0.895 *** | 0.809 *** | 1 |

Appendix C

References

- Acharya, Viral V., Heitor Almeida, and Murillo Campello. 2007. Is cash negative debt? A hedging perspective on corporate financial policies. Journal of Financial Intermediation 16: 515–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Heitor, Murillo Campello, and Michael S. Weisbach. 2004. The cash flow sensitivity of cash. Journal of Finance 59: 1777–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najjar, Basil. 2015. The effect of governance mechanisms on small and medium-sized enterprise cash holdings: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Journal of Small Business Management 53: 303–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najjar, Basil, and Yacine Belghitar. 2011. Corporate cash holdings and dividend payments: Evidence from simultaneous analysis. Managerial and Decision Economics 32: 231–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najjar, Basil, and Ephraim Clark. 2017. Corporate governance and cash holdings in MENA: Evidence from internal and external governance practices. Research in International Business and Finance 39: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, Edward I. 1968. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. The Journal of Finance 23: 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulou, Seraina C. 2013. Cash holdings: Determining factors and impact on future operating performance for listed versus unlisted firms. Review of Pacific Basin Financial Markets and Policies 16: 1350013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, Lalita M. Thenmozhi, Nikhil Varaiya, and Saumitra Bhadhuri. 2018. Impact of macroeconomic factors on cash holdings?: A dynamic panel model. Journal of Emerging Market Finance 17: S27–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, Manuel, and Olympia Bover. 1995. Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics 68: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Thomas W., Kathleen M. Kahle, and René M. Stulz. 2009. Why do U.S. firms hold so much than they used to? Journal of Finance 64: 1985–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, William J. 1952. The transactions demand for cash: An inventory theoretic approach. Quarterly Journal of Economics 66: 545–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Thorsten, Asli DemirgüÇ-Kunt, and Vojislav Maksimovic. 2005. Financial and legal constraints to growth: Does firm size matter? The Journal of Finance 60: 137–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelli, Marco, and Javier Sánchez-Vidal. 2012. Cash holdings in private firms. Journal of Banking & Finance 36: 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, and Stephen Bond. 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougheas, Spiros, Paul Mizen, and Cihan Yalcin. 2006. Access to external finance: theory and evidence on the impact of monetary policy and firm-specific characteristics. Journal of Banking and Finance 30: 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Michael, Gregg A. Jarrell, and E. Han Kim. 1984. On the existence of an optimal capital structure: Theory and evidence. Journal of Finance 39: 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, Ivan E., and Rose C. Liao. 2017. The joint determinants of cash holdings and debt maturity: the case for financial constraints. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 48: 597–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, Gary. 1984. Chapter 22 Panel data. Handbook of Econometrics 2: 1247–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yenn-Ru, and Wei-Tin Chuang. 2009. Alignment or entrenchment? Corporate governance and cash holdings in growing firms. Journal of Business Research 62: 1200–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Kee H., Jang-Chul Kim, Young Sang Kim, and Hao Zhang. 2015. Information asymmetry and corporate cash holdings. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 42: 1341–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, William G. 1977. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, Jeffrey L., and Zhichuan (Frank) Li. 2012a. An empirical assessment of empirical corporate finance. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, Jeffrey L., and Zhichuan (Frank) Li. 2012b. Managerial attributes, incentives, and performance. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, Jeffrey L., Naveen D. Daniel, and Lalitha Naveen. 2006. Managerial incentives and risk taking. Journal of Financial Economics 79: 431–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, Jeffrey L., Naveen D. Daniel, and Lalitha Naveen. 2008. Boards: does one size fit all? Journal of Financial Economics 87: 329–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core, John, and Wayne Guay. 1999. The use of equity grants to manage optimal equity incentive levels. Journal of Accounting and Economics 28: 151–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, Aswath. 2005. Dealing with cash, cross holdings and other non-operating assets: Approaches and implications. Stern School of Business, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Chongyu, Zhichuan (Frank) Li, and Chen Yang. 2018. Measuring firm size in empirical corporate finance. Journal of Banking & Finance 86: 159–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, Diane K., and John J. McConnell. 2003. International corporate governance. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 38: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, David J., and Valeriy Sibilkov. 2010. Financial constraints, investment, and the value of cash holdings. Review of Financial Studies 23: 247–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, Amy, and Jan Mahrt-Smith. 2007. Corporate governance and the value of cash holdings. Journal of Financial Economics 83: 599–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, Amy, Jan Mahrt-Smith, and Henri Servaes. 2003. International corporate governance and corporate cash holdings. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 38: 111–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, Ciaran, and Jair Muñoz-Bugarin. 2019. Financial constraints on investment: Effects of firm size and the financial crisis. Research in International Business and Finance 47: 441–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobetz, Wolfgang, and Matthias C. Grüninger. 2007. Corporate cash holdings: Evidence from Switzerland. Financial Markets and Portfolio Management 21: 293–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchin, Ran. 2010. Cash holdings and corporate diversification. The Journal of Finance 65: 955–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, William D., and Walton D. Plummer. 1998. Power and sample size calculations for studies involving linear regression. Controlled Clinical Trials 19: 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyasiani, Elyas, and Lin Zhang. 2015. CEO entrenchment and corporate liquidity management. Journal of Banking and Finance 54: 115–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Michael C. Jensen. 1983. Agency problems and residual claims. The Journal of Law and Economics 26: 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F., and James D. MacBeth. 1973. Risk, return, and equilibrium: Empirical tests. Journal of Political Economy 81: 607–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinha, Jorge, Cesario Mateus, and Nuno Soares. 2018. Cash holdings and earnings quality: Evidence from the main and alternative UK markets. International Review of Financial Analysis 56: 238–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkender, Michael W. 2002. Cash holdings among small businesses. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Miguel A., and Antonio S. Vilela. 2004. Why do firms hold cash? Evidence from EMU countries. European Financial Management 10: 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Teruel, Pedro J., and Pedro Martínez-Solano. 2008. On the determinants of SME cash holdings: Evidence from Spain. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 35: 127–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Amarjit, and Charul Shah. 2012. Determinants of corporate cash holdings: Evidence from Canada. International Journal of Economics and Finance 4: 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroud, Xavier, and Holger M. Mueller. 2011. Corporate Governance, Product Market Competition, and Equity Prices. The Journal of Finance 66: 563–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Seungjin, and Jiaping Qiu. 2007. Corporate precautionary cash holdings. Journal of Corporate Finance 13: 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, Jarrad. 1999. Corporate cash holdings and acquisitions. The Journal of Finance 54: 1969–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, Jarrad, Sattar A. Mansi, and William F. Maxwell. 2008. Corporate governance and firm cash holdings in the US. Journal of Financial Economics 87: 535–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, Jarrad, Sandy Klasa, and William F. Maxwell. 2014. Refinancing risk and cash holdings. Journal of Finance 69: 975–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Barry, and Theodorus W. Widjaja. 2013. Did the financial crisis impact on the capital structure of firms? Discussion Papers in Economics 5: 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Michael C. 1986. Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. American Economic Review 76: 323–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalcheva, Ivalina, and Karl V. Lins. 2007. International evidence on cash holdings and expected managerial agency problems. Review of Financial Studies 20: 1087–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keele, Luke, and Nathan J. Kelly. 2006. Dynamic models for dynamic theories: The ins and outs of lagged dependent variables. Political Analysis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilincarslan, Erhan. 2019. Smoothed or not smoothed: The impact of the 2008 global financial crisis on dividend stability in the UK. Finance Research Letters, 101423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Chang-Soo, David C. Mauer, and Ann E. Sherman. 1998. The determinants of corporate liquidity: Theory and evidence. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 33: 335–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, Alan, and Robert H. Litzenberger. 1973. A state-preference model of optimal financial leverage. Journal of Finance 28: 911–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusnadi, Yuanto. 2011. Do corporate governance mechanisms matter for cash holdings and firm value? Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 19: 554–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrenz, Jochen, and Julia Oberndorfer. 2018. Firm size effects in trade credit supply and demand. Journal of Banking & Finance 93: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Duc H., Phi L. Tran, Thu P. Ta, and Duy M. Vu. 2018. Determinants of corporate cash holding: evidence from UK listed firms. Business and Economic Horizons 14: 561–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyandres, Evgeny, and Berardino Palazzo. 2016. Cash holdings, competition, and innovation. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 51: 1823–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmillan, Iain, Sriram Prakash, and Russell Shoult. 2014. The Cash Paradox: How Record Cash Reserves Are Influencing Corporate Behaviour. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/corporate-finance/deloitte-uk-cash-paradox-jan-14.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- Mander, Adrian. 2005. Sampsi_reg: Stata Module to Calculate the Sample Size/Power for Linear Regression. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s456418.html (accessed on 16 November 2019).

- Martínez-Carrascal, Carmen. 2010. Cash holdings, firm size and access to external finance. Evidence for the euro area. Banco de Espana Working Paper Series 1034: 6–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Merton H., and Daniel Orr. 1966. A model of the demand for money by firms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 80: 413–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, Franco, and Merton H. Miller. 1958. The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. The American Economic Review XLVII: 261–97. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, Stewart C. 1977. Determinants of corporate borrowing. Journal of Financial Economics 5: 147–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Stewart C., and Nicholas S. Majluf. 1984. Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics 13: 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neamtiu, Monica, Nemit Shroff, Hal D. White, and Christopher D. Williams. 2014. The impact of ambiguity on managerial investment and cash holdings. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, Roger. 2004. Generalized power calculations for generalized linear models and more. Stata Journal 4: 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, Stephen. 1981. Biases in dynamic panel models with fixed effects. Econometrica 49: 1417–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, Mark, Matt Crane, Jenny Shutt, and Dan Georgescu. 2016. The UK’s Cash Conundrum Business Consulting. Available online: https://www.grantthornton.co.uk/globalassets/1.-member-firms/united-kingdom/pdf/publication/2016/working-capital-report-digital.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- Oler, Derek, and Marc Picconi. 2014. Implications of insufficient and excess cash for future performance. Contemporary Accounting Research 31: 253–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongsakul, Viput, Sirimon Treepongkaruna, Pornsit Jiraporn, and Ali Uyar. 2020. Do firms adjust corporate governance in response to economic policy uncertainty? Evidence from board size. Finance Research Letters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opler, Tim, Lee Pinkowitz, René Stulz, and Rohan Williamson. 1999. The determinants and implications of corporate cash holdings. Journal of Financial Economics 52: 3–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, Svetlana V., and Ramesh P. Rao. 2018. Cash holdings speed of adjustment. International Review of Economics and Finance 54: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, Aydin, and Neslihan Ozkan. 2004. Corporate cash holdings: An empirical investigation of UK companies. Journal of Banking and Finance 28: 2103–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Alves, Paulo F., and Francisco Morais. 2018. Cash holdings are increasing and financial crisis strengths it. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkowitz, Lee, Rohan Williamson, and René M. Stulz. 2007. Cash holdings, dividend policy, and corporate governance: A cross-country analysis. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 19: 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, Raghuram G., and Luigi Zingales. 1995. What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. The Journal of Finance 50: 1421–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddick, Leigh A., and Toni M. Whited. 2009. The corporate propensity to save. The Journal of Finance 64: 1729–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, David. 2009. How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in stata. Stata Journal 9: 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathian, Brijesh, Jayadevan Sreedharan, Suresh N. Baboo, Krishna Sharan, E. S. Abhilash, and E. Rajesh. 2010. Relevance of sample size determination in medical research. Nepal Journal of Epidemiology 1: 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Ajay S., and Micah B. Masuku. 2014. Sampling techniques and determination of sample size in applied statistics research: An overview. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management 2: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, Venkat, Tony T. Tang, Heng Yue, and Xin Zhou. 2011. Firm structure and corporate cash holdings. Journal of Corporate Finance 17: 759–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, James. 1956. The interest-elasticity of transactions demand for cash. Review of Economics and Statistics 38: 241–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Zhenxu. 2010. CEO risk incentives and corporate cash holdings. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 37: 1248–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkiteshwaran, Vinod. 2011. Partial adjustment toward optimal cash holding levels. Review of Financial Economics 20: 113–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidemann, Jan F. 2018. A state-of-the-art review of corporate cash holding research. Journal of Business Economics 88: 765–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, Arjun S. 2018. To lag or not to lag?:Re-evaluating the use of lagged dependent variables in regression analysis. Political Science Research and Methods 6: 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Regarding the agency costs, we use the definition given by Fama and Jensen (1983): “the costs of structuring, monitoring, and bonding a set of contracts among agents with conflicting interests, plus the residual loss incurred because the cost of full enforcement of contracts exceeds the benefits”. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | Following Denis and Mcconnell (2003), we define corporate governance as “the set of mechanisms—both institutional and market-based—that induce the self-interested controllers of a company (those that make decisions regarding how the company will be operated) to make decisions that maximize the value of the company to its owners (the suppliers of capital)”. |

| 4 | A relevant variable missing from the analysis is dividends paid in the fiscal year to assets or a dummy variable taking the value of one when a firm distributes dividends in the fiscal year, and zero otherwise (Ozkan and Ozkan 2004); the Amadeus database does not report the relevant financial data for the calculations. However, Ozkan and Ozkan (2004) find that dividend payout has a no significant influence on corporate cash holdings in the UK case. |

| 5 | Wilkins (2018) suggests that the exclusion of lagged dependent variables (LDVs) could result in biased estimates. In other words, LDVs should largely be considered as a robustness check by studies. Keele and Kelly (2006) argue that if history matters, which stands for most cases in economics where most processes are dynamic, then the LDV model is the most appropriate technique. |

| 6 | Since T is fairly small in our analysis (nine years), the specification should not lead to biased coefficients. As stated by the previous literature (Chamberlain 1984; Nickell 1981), a dynamic model introduces correlation between the lagged dependent variable and time-averaged error term; the estimation problem is highly dependent on the number of years. |

| 7 | We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion. |

| 8 | Amadeus (Analyse Major Database from European Sources), compiled by Bureau Van Dijk Electronic Publishing (BvDEP), is a dataset that comprises financial information for public and private European companies. See www.bvdinfo.com. |

| 9 | We also run power calculations to overcome potential issues regarding the validity of our findings, which confirm that the sample size of the study is adequate to provide results with the desired power and significance. See Appendix C for further discussion. |

| 10 | We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion. |

| Variable | Prediction | Trade-off Theory (TOT) | Pecking Order Theory (POT) | Free Cash Flow Hypothesis (FCF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cash Flow (CF) | − | − | + | n.a. |

| Leverage (LEV) | − | −/+ | − | − |

| Debt maturity (LEV) | − | −/+ | − | − |

| Net working capital (NWC) | − | − | n.a. | n.a. |

| Firm size (SIZE) | − | − | + | + |

| Capital expenditures (CAPX) | − | − | + | n.a. |

| R&D (XRD) | + | − | + | n.a. |

| Industry sigma (INDSIGMA) | + | + | + | n.a. |

| Market to Book ratio (MTB) | + | + | + | − |

| Opportunity cost of holding liquid assets (RSPREAD) | ? | + | n.a. | n.a. |

| Panel A: By Year | |||||

| Year | Number of Firms | Percentage (%) | Year | Number of Firms | Percentage (%) |

| 2010 | 677 | 10.21 | 2015 | 824 | 12.43 |

| 2011 | 706 | 10.65 | 2016 | 857 | 12.93 |

| 2012 | 724 | 10.92 | 2017 | 869 | 13.11 |

| 2013 | 759 | 11.45 | 2018 | 411 | 6.20 |

| 2014 | 802 | 12.10 | Total | 6629 | 100.00 |

| Panel B: By Industry | |||||

| No | Description of Industry | Number of Firms | Percentage (%) | ||

| 1 | Consumer Non-durables: Food, Tobacco, Textiles, Apparel, Leather, Toys | 467 | 7.05 | ||

| 2 | Consumer Durables: Cars, TV’s, Furniture, Household Appliances | 105 | 1.58 | ||

| 3 | Manufacturing: Machinery, Trucks, Planes, Off Furn, Paper, Com Printing | 470 | 7.09 | ||

| 4 | Oil, Gas, and Coal Extraction and Products | 390 | 5.88 | ||

| 5 | Chemicals and Allied Products | 183 | 2.76 | ||

| 6 | Business Equipment: Computers, Software, and Electronic Equipment | 887 | 13.37 | ||

| 7 | Telephone and Television Transmission | 229 | 3.46 | ||

| 8 | Wholesale, Retail, and Some Services (Laundries, Repair Shops) | 890 | 13.43 | ||

| 9 | Healthcare, Medical Equipment, and Drugs | 248 | 3.74 | ||

| 10 | Other: Mines, Constr, BldMt, Trans, Hotels, Bus Serv, Entertainment | 2760 | 41.64 | ||

| Total | 6629 | 100.00 | |||

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | 25% | Median | 75% | Max | Obs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASH | 0.168 | 0.187 | 0.001 | 0.043 | 0.096 | 0.222 | 0.927 | 6629 |

| CF | 0.004 | 0.286 | −1.869 | −0.002 | 0.074 | 0.129 | 0.398 | 6629 |

| LEV | 0.172 | 0.208 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.117 | 0.263 | 1.400 | 6629 |

| NWC | −0.009 | 0.238 | −1.514 | −0.101 | −0.004 | 0.099 | 0.641 | 6629 |

| SIZE | 11.540 | 2.440 | 4.892 | 9.709 | 11.352 | 13.209 | 17.645 | 6629 |

| CAPX | 0.023 | 0.190 | −1.036 | −0.017 | 0.010 | 0.074 | 0.603 | 6629 |

| XRD | 0.082 | 0.441 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 4.018 | 6629 |

| INDSIGMA | 0.087 | 0.046 | 0.002 | 0.046 | 0.096 | 0.122 | 0.278 | 6629 |

| MTB | 2.095 | 2.212 | 0.361 | 1.034 | 1.474 | 2.294 | 20.353 | 6035 |

| RSPREAD | −0.529 | 0.779 | −23.999 | −0.623 | −0.425 | −0.283 | 37.321 | 6610 |

| V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V8 | V9 | V10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1: CASH | 1 | −0.090 *** | −0.479 *** | −0.007 | −0.339 *** | −0.072 *** | 0.155 *** | 0.138 *** | 0.343 *** | −0.110 *** |

| V2: CF | −0.308 *** | 1 | 0.028 * | 0.097 *** | 0.374 *** | 0.149 *** | −0.005 | −0.184 *** | 0.192 *** | 0.528 *** |

| V3: LEV | −0.291 *** | −0.094 *** | 1 | −0.231 *** | 0.379 *** | 0.021 | −0.130 *** | −0.120 *** | −0.130 *** | 0.041 ** |

| V4: NWC | −0.052 *** | 0.270 *** | −0.342 *** | 1 | −0.000 | −0.027 * | 0.115 *** | −0.129 *** | −0.081 *** | 0.141 *** |

| V5: SIZE | −0.373 *** | 0.437 *** | 0.199 *** | 0.108 *** | 1 | 0.090 ** | −0.104 *** | −0.232 *** | −0.117 *** | 0.352 *** |

| V6: CAPX | −0.106 *** | 0.219 *** | −0.063 *** | 0.069 *** | 0.102 *** | 1 | 0.009 | 0.022 | 0.148 *** | 0.137 *** |

| V7: XRD | 0.342 *** | −0.268 *** | −0.096 *** | 0.026 * | −0.155 *** | −0.006 | 1 | 0.025 * | 0.234 *** | −0.082 *** |

| V8: INDSIGMA | 0.171 *** | −0.208 *** | −0.063 *** | −0.152 *** | −0.220 *** | −0.001 | 0.117 *** | 1 | 0.060 *** | −0.168 *** |

| V9: MTB | 0.336 *** | −0.359 *** | 0.049 *** | −0.237 *** | −0.242 *** | −0.002 | 0.230 *** | 0.096 *** | 1 | 0.055 *** |

| V10: RSPREAD | −0.115 *** | 0.516 *** | −0.055 *** | 0.212 *** | 0.243 *** | 0.173 *** | −0.123 *** | −0.107 *** | −0.165 *** | 1 |

| VIF | 1.91 | 1.26 | 1.27 | 1.42 | 1.07 | 1.15 | 1.10 | 1.23 | 1.35 |

| First Quartile | Second Quartile | Third Quartile | Forth Quartile | t-Stat. (p-Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range CASH | 0.001 | 0.043 | 0.096 | 0.222 | |

| 0.043 | 0.096 | 0.222 | 0.927 | ||

| CASH | 0.021 | 0.067 | 0.150 | 0.433 | −88.17 |

| [0.021] | [0.068] | [0.143] | [0.370] | (0.00) | |

| CF | 0.034 | 0.053 | 0.038 | −0.110 | 12.36 |

| [0.075] | [0.078] | [0.083] | [0.042] | (0.00) | |

| LEV | 0.243 | 0.219 | 0.148 | 0.077 | 24.57 |

| [0.218] | [0.195] | [0.083] | [0.000] | (0.00) | |

| NWC | −0.021 | 0.010 | 0.006 | −0.032 | 1.24 |

| [−0.014] | [0.001] | [0.006] | [−0.007] | (0.21) | |

| SIZE | 12.154 | 12.461 | 11.464 | 10.083 | 27.05 |

| [12.107] | [12.448] | [11.258] | [9.941] | (0.00) | |

| CAPX | 0.031 | 0.036 | 0.028 | −0.005 | 5.27 |

| [0.017] | [0.016] | [0.013] | [0.000] | (0.00) | |

| XRD | 0.012 | 0.019 | 0.036 | 0.259 | −12.27 |

| [0.000] | [0.000] | [0.000] | [0.000] | (0.00) | |

| INDSIGMA | 0.082 | 0.085 | 0.086 | 0.097 | −9.87 |

| [0.075] | [0.087] | [0.089] | [0.109] | (0.00) | |

| MTB | 1.502 | 1.681 | 1.998 | 3.246 | −18.65 |

| [1.206] | [1.337] | [1.528] | [2.210] | (0.00) | |

| RSPREAD | −0.495 | −0.462 | −0.505 | −0.653 | 4.83 |

| [−0.408] | [−0.400] | [−0.405] | [−0.520] | (0.00) |

| Dependent Variable: CASH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| L.CASH | 0.730 *** | |||||

| (66.68) | ||||||

| SIZE | −0.014 *** | −0.014 *** | −0.022** | −0.014 *** | −0.014 *** | −0.005 *** |

| (−6.92) | (−6.93) | (−3.06) | (−6.87) | (−17.26) | (−6.13) | |

| CF | −0.075** | −0.078 *** | 0.061 | −0.051 ** | −0.083 *** | 0.051 *** |

| (−3.31) | (−3.40) | (1.84) | (−2.41) | (−4.18) | (6.80) | |

| LEV | −0.256 *** | −0.251 *** | −0.255 *** | −0.254 *** | −0.276 *** | −0.113 *** |

| (−7.69) | (−7.39) | (−4.94) | (−7.97) | (−14.95) | (−6.01) | |

| NWC | −0.041 | −0.037 | −0.181 ** | −0.035 | −0.064 *** | −0.051 *** |

| (−1.65) | (−1.47) | (−2.77) | (−1.44) | (−5.85) | (−4.41) | |

| DEBTMT | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.076 * | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.038 ** |

| (0.60) | (0.36) | (2.18) | (0.62) | (1.51) | (3.14) | |

| CAPX | −0.090 *** | −0.092 *** | −0.101 *** | −0.084 *** | −0.092 *** | −0.161 *** |

| (−8.06) | (−7.43) | (−5.65) | (−7.63) | (−7.36) | (−12.81) | |

| XRD | 0.085 *** | 0.086 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.085 *** | 0.102 *** | 0.033 *** |

| (7.45) | (7.31) | (5.73) | (7.66) | (14.28) | (6.14) | |

| INDSIGMA | 0.328 ** | 0.347 | 0.296 ** | 0.393 *** | 0.122 *** | 0.172 ** |

| (2.89) | (1.54) | (3.31) | (3.78) | (6.04) | (2.98) | |

| MTB | 0.017 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.007 * | 0.017 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.006 *** |

| (7.54) | (7.47) | (2.05) | (7.94) | (10.13) | (4.79) | |

| INT | 0.011 | |||||

| (0.52) | ||||||

| GDPGR | 0.006 | |||||

| (1.25) | ||||||

| RSPREAD | 0.018 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.005 | 0.023 ** | −0.005 | |

| (4.68) | (4.72) | (1.29) | (2.72) | (−0.64) | ||

| Year FE | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Industry FE | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Industry × Year FE | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Firm FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| N | 6021 | 5935 | 5963 | 6034 | 6022 | 5062 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.375 | 0.347 | 0.746 | 0.370 | 0.363 | 0.736 |

| Dependent Variable: CASH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | Full Sample | Full Sample | Full Sample | Small Firms Only | Medium Firms Only | Large Firms Only |

| SIZEDUMMY | −0.030 *** | |||||

| (−3.38) | ||||||

| SMALL vs. LARGE | −0.105 *** | |||||

| (−5.87) | ||||||

| MEDIUM vs. LARGE | −0.018 * | |||||

| (−2.19) | ||||||

| CF | −0.113 *** | −0.074 *** | −0.080 * | −0.084 *** | −0.074 | −0.049 |

| (−5.21) | (−3.48) | (−2.14) | (−3.71) | (−1.63) | (−1.27) | |

| LEV | −0.251 *** | −0.284 *** | −0.170 *** | −0.372 *** | −0.219 *** | 0.006 |

| (−7.28) | (−6.82) | (−4.97) | (−6.33) | (−4.49) | (0.16) | |

| NWC | −0.035 | −0.019 | −0.073 *** | −0.017 | −0.065 ** | −0.086 ** |

| (−1.40) | (−0.63) | (−3.58) | (−0.42) | (−2.40) | (−3.22) | |

| DEBTMT | −0.022 | 0.057 * | −0.049 ** | 0.112 * | −0.062 ** | −0.090 *** |

| (−1.10) | (2.29) | (−2.50) | (2.12) | (−2.41) | (−3.75) | |

| CAPX | −0.091 *** | −0.092 *** | −0.080 *** | −0.105 *** | −0.084 *** | −0.075 ** |

| (−7.72) | (−4.82) | (−6.39) | (−3.64) | (−5.41) | (−3.04) | |

| XRD | 0.084 *** | 0.077 *** | 0.094 *** | 0.069 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.114 |

| (7.26) | (5.98) | (4.97) | (5.10) | (4.21) | (1.11) | |

| INDSIGMA | 0.355 ** | 0.398 ** | 0.210 * | 1.264 *** | 0.326 * | 0.070 |

| (3.35) | (3.33) | (2.02) | (4.31) | (1.96) | (0.62) | |

| MTB | 0.017 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.023 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.023 *** | 0.022 *** |

| (7.66) | (7.20) | (6.74) | (7.46) | (6.19) | (4.74) | |

| RSPREAD | 0.017 *** | 0.018 *** | −0.030 | 0.019 *** | −0.037 | 0.044 |

| (4.96) | (6.05) | (−1.48) | (6.12) | (−1.65) | (1.23) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 6020 | 2989 | 4635 | 1385 | 3031 | 1603 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.360 | 0.427 | 0.330 | 0.322 | 0.327 | 0.330 |

| Dependent Variable: CASH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| L.CASH | 0.728 *** | 0.727 *** | 0.727 *** | |||

| (55.89) | (55.63) | (56.80) | ||||

| SIZE | −0.013 *** | −0.016 *** | −0.013 *** | −0.005 *** | −0.005 *** | −0.005 *** |

| (−6.48) | (−5.75) | (−6.53) | (−6.15) | (−4.17) | (−5.62) | |

| CF | −0.083 *** | −0.083 *** | −0.083 *** | 0.064 *** | 0.064 *** | 0.064 *** |

| (−3.63) | (−3.62) | (−3.62) | (5.27) | (5.26) | (5.15) | |

| LEV | −0.264 *** | −0.260 *** | −0.264 *** | −0.117 *** | −0.117 *** | −0.118 *** |

| (−7.21) | (−7.20) | (−7.22) | (−7.29) | (−7.22) | (−7.29) | |

| NWC | −0.045 | −0.045 | −0.045 | −0.052 *** | −0.052 *** | −0.052 *** |

| (−1.71) | (−1.73) | (−1.72) | (−3.73) | (−3.78) | (−3.70) | |

| DEBTMT | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.037 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.037 *** |

| (0.59) | (0.57) | (0.64) | (3.66) | (3.59) | (3.73) | |

| CAPX | −0.090 *** | −0.090 *** | −0.090 *** | −0.162 *** | −0.162 *** | −0.162 *** |

| (−7.70) | (−7.68) | (−7.73) | (−13.22) | (−13.25) | (−13.13) | |

| XRD | 0.081 *** | 0.081 *** | 0.081 *** | 0.032 *** | 0.032 *** | 0.032 ** |

| (6.72) | (6.71) | (6.71) | (3.64) | (3.74) | (3.39) | |

| INDSIGMA | 0.304 ** | 0.302 ** | 0.304 ** | 0.177 ** | 0.176 ** | 0.177 ** |

| (2.56) | (2.53) | (2.57) | (3.21) | (3.16) | (3.21) | |

| MTB | 0.017 *** | 0.016 *** | 9.687 * | 0.006 *** | 0.006 *** | 1.583 |

| (6.67) | (6.33) | (2.13) | (4.29) | (3.90) | (0.33) | |

| RSPREAD | 0.017 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.017 *** | −0.014 | −0.014 | −0.014 |

| (4.15) | (4.20) | (4.15) | (−1.67) | (−1.68) | (−1.62) | |

| MAN | −0.409 ** | −0.385 ** | −0.035 | −0.049 | −0.048 | 0.009 |

| (−2.72) | (−2.62) | (−0.15) | (−1.45) | (−1.32) | (0.05) | |

| MAN2 | 0.006 ** | 0.005 ** | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.000 |

| (2.69) | (2.58) | (0.10) | (1.41) | (1.27) | (−0.08) | |

| MAN3 | −0.000 ** | −0.000 ** | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 |

| (−2.66) | (−2.55) | (−0.06) | (−1.37) | (−1.22) | (0.09) | |

| MTB × MAN | −0.418 * | −0.069 | ||||

| (−2.10) | (−0.34) | |||||

| MTB × MAN2 | 0.006 * | 0.001 | ||||

| (2.06) | (0.34) | |||||

| MTB × MAN3 | −0.000 * | −0.000 | ||||

| (−2.00) | (−0.34) | |||||

| CEO_COB | −0.020 | 0.001 | ||||

| (−0.48) | (0.21) | |||||

| BOARDN | 0.009 | 0.002 | ||||

| (1.20) | (0.50) | |||||

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 5635 | 5635 | 5635 | 4747 | 4747 | 4747 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.372 | 0.372 | 0.372 | 0.731 | 0.731 | 0.731 |

| Dependent Variable: CASH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Herfindahl–Hirschman Index | Altman Z-Score | Firm Age | ||||

| Variables | Low industry rivalry (Above yearly HHI median) | High industry rivalry (Below yearly HHI median) | Strong balance sheet (Above yearly Median) | Weak balance sheet (Below yearly Median) | Young (<5 years from foundation date) | Mature (>5 years from foundation date) |

| SIZE | −0.013 *** | −0.016 * | −0.014 *** | −0.009 *** | −0.019 ** | −0.014 *** |

| (−6.62) | (−2.60) | (−4.96) | (−4.45) | (−2.57) | (−6.24) | |

| CF | −0.075 ** | −0.056 | 0.131 | −0.112 *** | −0.077 | −0.057 ** |

| (−3.19) | (−1.52) | (1.62) | (−5.18) | (−0.96) | (−2.59) | |

| LEV | −0.280 *** | −0.182 * | −0.179 *** | −0.168 *** | −0.332 ** | −0.241 *** |

| (−8.21) | (−2.21) | (−3.76) | (−4.32) | (−3.20) | (−6.38) | |

| NWC | −0.055 | 0.006 | −0.095 *** | 0.012 | −0.174 * | −0.033 |

| (−1.89) | (0.20) | (−3.85) | (0.32) | (−2.18) | (−1.27) | |

| DEBTMT | 0.018 | 0.001 | −0.038 | 0.012 | −0.005 | 0.007 |

| (0.85) | (0.04) | (−1.39) | (0.43) | (−0.06) | (0.32) | |

| CAPX | −0.096 *** | −0.046 * | −0.124 *** | −0.046 ** | −0.142 *** | −0.087 *** |

| (−7.54) | (−2.19) | (−5.75) | (−2.96) | (−4.38) | (−5.68) | |

| XRD | 0.082 *** | 0.113 *** | 0.230 | 0.082 *** | 0.025 | 0.098 *** |

| (7.10) | (14.79) | (1.70) | (8.15) | (0.97) | (8.95) | |

| INDSIGMA | 0.336 ** | −0.033 | 0.057 | 0.112 | 0.767 * | 0.282 ** |

| (2.83) | (−0.26) | (0.47) | (0.77) | (1.91) | (2.32) | |

| MTB | 0.017 *** | 0.014 *** | 0.014 ** | 0.016 *** | 0.015 * | 0.016 *** |

| (8.07) | (6.19) | (2.32) | (4.52) | (2.11) | (6.59) | |

| RSPREAD | 0.018 *** | 0.003 | 0.016 *** | 0.020 ** | 0.022 | 0.017 *** |

| (4.76) | (0.11) | (7.45) | (2.86) | (0.59) | (5.22) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 5036 | 976 | 2523 | 2748 | 622 | 5399 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.376 | 0.360 | 0.346 | 0.353 | 0.376 | 0.389 |

| Dependent Variable = CASH | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Variables | Two-Step GMM | Two-Step GMM |

| L.CASH | 0.428 *** | 0.375 *** |

| (28.96) | (40.75) | |

| SIZE | −0.015 *** | −0.016 *** |

| (−3.54) | (−7.27) | |

| CF | −0.002 | 0.083 *** |

| (−0.18) | (12.98) | |

| LEV | −0.250 *** | −0.170 *** |

| (−20.04) | (−13.02) | |

| NWC | −0.174 *** | −0.150 *** |

| (−10.41) | (−12.42) | |

| DEBTMT | 0.129 *** | 0.074 *** |

| (13.10) | (10.32) | |

| CAPX | −0.089 *** | −0.122 *** |

| (−9.40) | (−22.92) | |

| XRD | 0.034 * | 0.028 *** |

| (1.91) | (9.08) | |

| INDSIGMA | 0.211 *** | 0.255 *** |

| (4.46) | (6.55) | |

| MTB | 0.002 | 0.006 *** |

| (1.35) | (6.40) | |

| RSPREAD | 0.008 | −0.008 *** |

| (1.06) | (−2.70) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | No |

| Firm FE | No | Yes |

| No firms | 878 | 878 |

| N | 5062 | 5062 |

| AR(1) (p-value) | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AR(2) (p-value) | 0.063 | 0.126 |

| Hansen (p-value) | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Dependent Variable: CASH | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010–2012 | 2013–2015 | 2016–2018 | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| SIZE | −0.011 ** | −0.014 ** | −0.016 ** |

| (−4.62) | (−5.00) | (−6.14) | |

| CF | −0.030 | −0.049 | −0.129 ** |

| (−0.91) | (−2.11) | (−5.51) | |

| LEV | −0.298 ** | −0.240 ** | −0.233 ** |

| (−7.84) | (−4.75) | (−5.47) | |

| NWC | −0.056 | −0.012 | −0.061 |

| (−1.83) | (−0.33) | (−1.85) | |

| DEBTMT | 0.028 | −0.002 | 0.004 |

| (1.21) | (−0.07) | (0.16) | |

| CAPX | −0.126 ** | −0.067 ** | −0.093 ** |

| (−5.87) | (−4.72) | (−7.08) | |

| XRD | 0.101 ** | 0.096 ** | 0.061 ** |

| (7.34) | (6.11) | (5.04) | |

| INDSIGMA | 0.415 | 0.383 | 0.174 |

| (2.08) | (2.01) | (1.52) | |

| MTB | 0.017 ** | 0.015 ** | 0.018 ** |

| (4.77) | (6.20) | (5.98) | |

| RSPREAD | 0.019 * | −0.003 | 0.032 ** |

| (3.60) | (−0.32) | (5.56) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1851 | 2155 | 2015 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.389 | 0.351 | 0.386 |

| Dependent Variable: CASH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| L.CASH | 0.709 *** | 0.725 *** | 0.735 *** | |||

| (64.00) | (64.88) | (67.51) | ||||

| SIZENA | −0.025 *** | −0.010 *** | ||||

| (−10.49) | (−7.18) | |||||

| SIZE1 | −0.015 *** | −0.006 *** | ||||

| (−7.94) | (−4.42) | |||||

| SIZE2 | −0.008 *** | −0.003 *** | ||||

| (−4.01) | (−4.10) | |||||

| CF | −0.033 | −0.052 * | −0.093 *** | 0.063 *** | 0.059 *** | 0.047 *** |

| (−1.41) | (−2.29) | (−4.21) | (8.74) | (8.31) | (6.23) | |

| LEV | −0.249 *** | −0.234 *** | −0.263 *** | −0.114 *** | −0.106 *** | −0.115 *** |

| (−8.02) | (−7.07) | (−7.61) | (−6.14) | (−5.59) | (−6.03) | |

| NWC | −0.046 * | −0.041 | −0.036 | −0.053 *** | −0.051 *** | −0.049 *** |

| (−1.97) | (−1.66) | (−1.42) | (−4.71) | (−4.41) | (−4.12) | |

| DEBTMT | 0.055 ** | −0.005 | −0.010 | 0.055 *** | 0.032 ** | 0.033 ** |

| (2.94) | (−0.26) | (−0.52) | (4.46) | (2.66) | (2.68) | |

| CAPX | −0.086 *** | −0.100 *** | −0.087 *** | −0.158 *** | −0.164 *** | −0.160 *** |

| (−8.30) | (−8.99) | (−7.40) | (−13.04) | (−13.11) | (−12.95) | |

| XRD | 0.080 *** | 0.074 *** | 0.085 *** | 0.033 *** | 0.030 *** | 0.033 *** |

| (7.72) | (6.86) | (7.42) | (6.54) | (5.44) | (6.05) | |

| INDSIGMA | 0.273 * | 0.288 ** | 0.350 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.157 ** | 0.177 ** |

| (2.27) | (2.55) | (3.12) | (2.48) | (2.55) | (3.14) | |

| MTB | 0.015 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.007 *** |

| (7.34) | (7.86) | (8.33) | (4.74) | (5.26) | (4.96) | |

| RSPREAD | 0.017 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.018 *** | −0.004 | −0.006 | −0.006 |

| (3.86) | (4.23) | (4.74) | (−0.49) | (−0.68) | (−0.67) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 6021 | 6021 | 6010 | 5062 | 5062 | 5053 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.419 | 0.386 | 0.363 | 0.743 | 0.738 | 0.736 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magerakis, E.; Gkillas, K.; Tsagkanos, A.; Siriopoulos, C. Firm Size Does Matter: New Evidence on the Determinants of Cash Holdings. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13080163

Magerakis E, Gkillas K, Tsagkanos A, Siriopoulos C. Firm Size Does Matter: New Evidence on the Determinants of Cash Holdings. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2020; 13(8):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13080163

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagerakis, Efstathios, Konstantinos Gkillas, Athanasios Tsagkanos, and Costas Siriopoulos. 2020. "Firm Size Does Matter: New Evidence on the Determinants of Cash Holdings" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13, no. 8: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13080163

APA StyleMagerakis, E., Gkillas, K., Tsagkanos, A., & Siriopoulos, C. (2020). Firm Size Does Matter: New Evidence on the Determinants of Cash Holdings. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(8), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13080163