2. Trimetallic Standard of Pre-Renaissance

The history of town coinage can be traced back to the early antiquity of towns and cities. The Italian city-state of Florence issued the first recorded city-backed bond. These bonds were endorsed through the legislation of 1344 and 1345. This debt was called the Monte Commune. Monte in Italian means both mountains and funds. In addition to the localized financial structures of cities, the citizens of diverse communities used parallel and multiple metallic means of payment for daily transaction needs. Coins and tokens of lower value metal were among daily trade and commerce activities.

The history of the United States, Napoleonic France and medieval Europe all suggest the existence of three kinds of currency, which the most inexpensive type of currency was to play as a facilitator of micro-level trade and transactions in isolated towns and localities. In medieval Europe, the currency of the high rate of circulation called black currency, and in parallel, there were depreciated metallic coins of (up to 98%) silver coin.

To mention only its main characteristics, it was a system based on a standard reference unit used to create two different types of currencies: a standard currency made up of gold and silver coins (acceptable for distant trade), and a set of small pieces of copper and other metallic substance, referred to as black currency, used mainly in towns and townships for local trade as currency. They were usually classified into four groups of coins, méreau (plural méreaux), tokens (jetton), and official currency (primarily for tax purposes).

Since these currencies were made of lower value metal and they would become rusted, they bear the label of black money. In the pre-Napoleon era, a specific term applied. The term “mereau” refers to kinds of vouchers and token that were used as signs of verification, such as pass or a substitute currency during periods of monetary shortage. The mereaux had a shape close to tokens or coins: they were mostly made of cheaper metal slices on which symbols were inscribed. The name “mereau” comes from the Latin “merere” which means “to be worthy, to deserve” (

Kennedy et al. 2012). In the Middle Ages, they were referred to as “merel, merelle, marelles and mereaulx”. Mereau predates token, and it seems to serve more divine and religious purposes; in reality, the church prohibited using the currency for an extended period. Mereaux and tokens were monetized objects that were not certified currencies, but they arose to be used for accounting and measurement purposes during history.

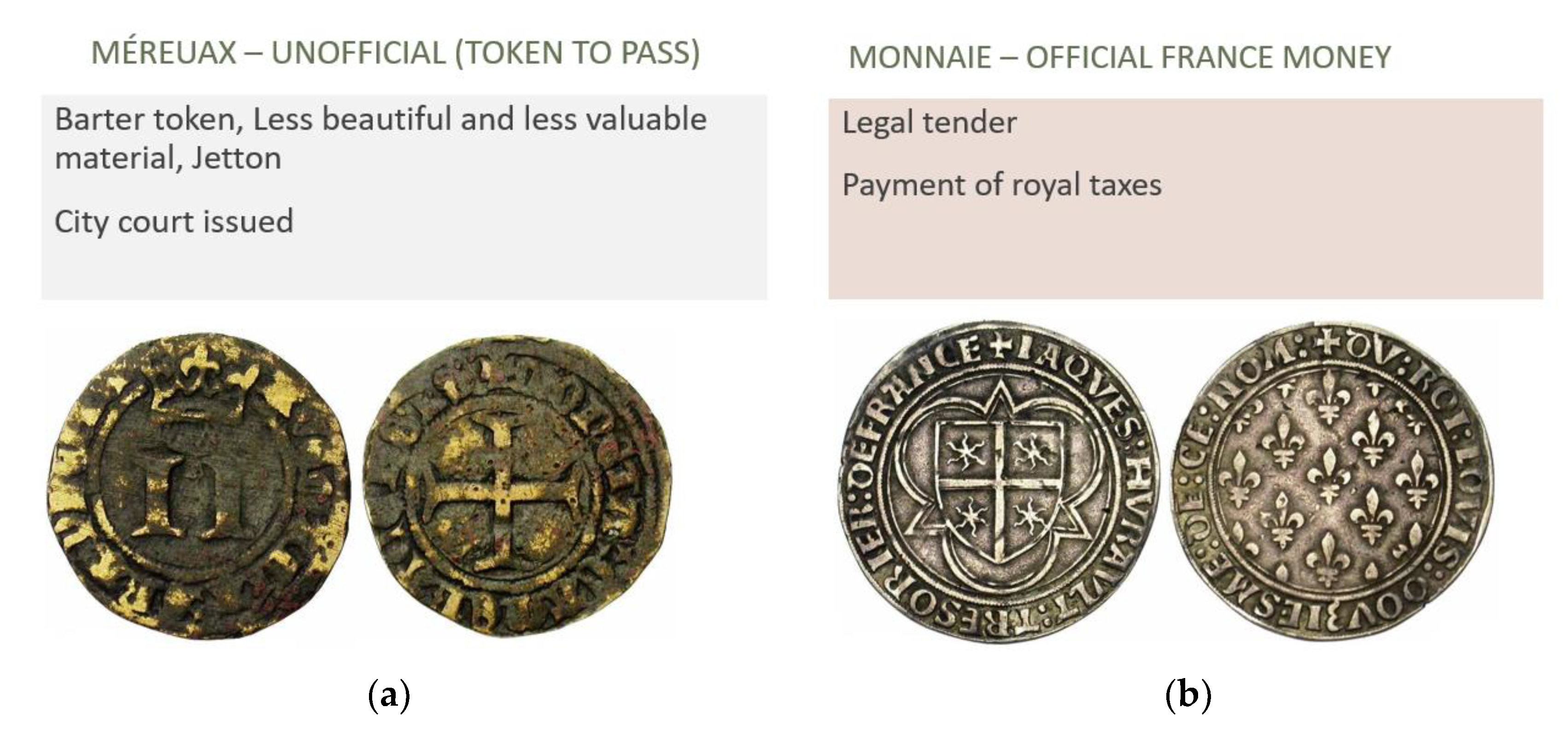

As depicted in

Figure 1, two different currencies were used for different social purposes (

Anonymous 1987), as various authorities were responsible for issuance, authorization, and legality judgment.

In the fifteenth century, mereaux were created with an equivalent weight value. Therefore, it could be converted into a common currency. Due to the inferior value of the metallic substance, they usually were not subject to be taxed.

Abbeys, chapters, and monasteries used them from the thirteenth century (

Courtenay 1972); they were used as a token of attendance by the canons (priest) at the offices and cathedral chapters to give them the right to a meal or a portion of bread. Since issued by religious authorities, they could not bear interest; they mostly represent a mereau (jeton) and a certificate for the voluntary work done for churches. Méreaux issued by a religious and charter community could then circulate all around the township like other coins in circulation. The record of mereaux is mostly documented in French sources; there are limited references in the English historical records.

These coins exhibit local circulation and have rarely been recorded being used and circulated externally. In principle, their use was only internal and local. Churches and chapters issued those coins in order to pay for monks attending prayers and other services. These tokens were mainly donated as charity to the poor. They became usable then serviceable inside the community, allowing holders to obtain food, drinks, or clothing. Occasionally, chapters paid for persons offering their services for wine production or building repairs; those tokens were then useable inside the section but also, for example, in taverns whose wine came from the chapter. Since these tokens or mereaux were the product of labor, hereafter, they represent undocumented and unrecorded added value to the local economy. Hence the majority of these Cathedrals were built by people of trade and craftsmen, artists, painters, poets all formed thriving projects.

In the middle ages (

Freeman 1946), medical intern students paid in jetons in order to participate in the medical visits; this practice was traced back to the Ayyubids system (

Ashtor 1976) of medical training and education (

Anjum 2002).

The seeds of Renaissance were planted partly through the local monetary autonomy of towns and townships. The mereaux represent certificates of produced work and labor and accumulated added value to the economy, earned value. They extended the product of labor materialized in the form of metallic coins; a time-based labor certificate was not a gold standard but a labor-hour standard; an authentic method to acknowledge and record newly created wealth into the local economy. The local economy flourished by the high circulation of metallic specimens, not issuing and inflating the quantity of monies in circulation.

In such a process, money created through the authentic work of labor acts as a miner who mines for the precious metal; the mine is the labor hour, but the metal is the circulating coins. The mereaux and tokens alike appeared mainly as a consequence of the shortage of main (official) currencies. The church buildings needed repair and the tokens represent a ledger of performed work. The nature or purpose of these accounts were recorded in the legend of the tokens.

In an agrarian economy, as production and consumption are based on a small variety of goods, the exchange process is not complicated even when the money supply is low. In such economies, what was needed was more cheap money, which circulates more frequently and carries economic activities. These tokens represent the total volume of work performed.

For instance, a building worker in the church would spend an earned token (mereau) in town. Hence the mereau was transformed into a parallel currency to others in circulation. Though, in terms of monetary value, the majority of these tokens were valued equaling to a loaf of bread or near meal value. Thus, a loaf of bread had been a unit of account and measurement for micropayments; essentially, one of the definitions of the mereau is to count. They served to perform the micropayments of daily necessities.

We know that the gold standard stabilized as a weight-based currency afterward, not a value standard, as Rothbard referred to it not as a medium of exchange but a unit of weight and measurement.

The dollar, for example, was defined as 1/20 of a gold ounce, the pound sterling as slightly less than ¼ of a gold ounce; a dinar, a coin of the Saracens in Spain and many Arab countries today, originally contained 65 gold grains, when was first coined at the end of the seventh century. (

Mitchiner et al. 1988) recorded that mereaux were 96.5% copper ingredient, those mereaux applications lasted until the French Revolution. As discussed, a sudo-vivid picture can be concluded to demonstrate the realism of the currencies of the time. A Trimetallic, as depicted in

Table 1, standard renders what might have been missing from economic history subjects.

As reported, in contrast with official currencies (

Spufford 1988), these local or complementary currencies tended to be cheap, easy to earn, and formed an exchange-oriented currency. Since the banking sector was developed later by the Medici, this method substituted the needed credit for low paying labor.

Therefore, tokens and mereaux accounted for black currency in that era. In other words, we may characterize the Renaissance as an authentic trimetallic standard.

3. Token as Complementary Currency

Both Mesopotamians and ancient Egyptian society applied diverse systems of monies prior to metallic coins. The earliest recorded forms of money in those communities were not out of metals, gold, or silver, nevertheless rather based on a barter exchange of food, grains, crops and the daily necessities of people. Unearthed cuneiform cone and tablet represented an accounting ledger of the exchange of grains and crops. Owing to the presence of Nile, Egypt was the breadbasket for the ancient world. As these were not used for investment, the currency in the form of the metallic substance was invested in economic production and needed investments that would turn into capital assets such as land, tools and irrigation schemes. Well recorded grain, oil, and crops were among several types of monies in ancient Egyptian civilization. It offers a measurement tool of a monetary system, and it satisfies the definition of money as a measurement of value, not the value itself.

Nevertheless, due to perishability and limited durability of foods, crops, and grains, the Egyptian grain standard used a demurrage feature. In ancient Egypt, when a farmer stored grain, he would receive a token, which was exchangeable and became a type of currency. If he returned a year later with ten tokens, he would only get nine tokens worth of grain, since rats and spoilage would have diminished the quantities, and since the guards at the storage facility had to be compensated, accordingly, considering the amounted and accounted as the demurrage charge.

In actuality, the Egyptian grain standard applied depreciation for the value of money as time elapsed. The certificate or the currency which denoted specific the value and volume of grain would depreciate with respect to its crop equivalence. In ancient Mesopotamia, Ziggurats were crop storage units in old Mesopotamia. In ancient Mesopotamia, Ziggurat (temple) guards would charge a demurrage fee per annum to preserve the farmers’ grains in storage (

Hudson 2003).

In recent history, we witnessed the reappearance of these types of currencies. In 1932, (

Barinaga 2020) Silvio Gesell was the architect of the labor value certificate in the Austrian Worgl municipality, in which Worgl was issued as one to one to the national currency. As an economist and advisor promoted the Austrian town of Worgl to prosper by issuing its own currency through city municipality, later, a few currencies adopted the Gesell theory and challenged the standard Keynesian model. The Worgl was equivalent to a schilling deposited with the local Raiffeisenbank. It was likely to switch back to the local currency for a fee of two percent. In the middle of a deflationary environment with high unemployment, this experience gained impressive economic successes. The mayor Michael Unterguggenberger utilized the monetary theory introduced by (

Gesell 1958). In 1933 a ban was issued by the superior authority in Kufstein on the warning from the Austrian National Bank (

Kennedy et al. 2012), in which it stated that the municipality with the issuing currency would have exceeded their powers. This experience remained as a success story for complementary currencies. The Worgl experience was so successful that it became known as “Das Wunder von Worgl,” impressing both John Maynard Keynes and Irving Fisher. Irvin Fisher replicated the Worgl experience in the US following the great depression.

In the United States, around 1934, we know that trade with scrip involved food, clothes, medical services and musical instruments; it is estimated that a secondary currency was not used mainly in trade and commerce.

In the fourteen century, Nicolas

Oresme (

1956) noted that it was necessary to distinguish between the currencies used for payments and those used for savings. Later, Gresham restated Oresme’s statement in the law that bears his name (

Kennedy et al. 2012), articulated as: “Bad money chases good.” Like high intrinsic value currencies (“Good money”) will be hoarded, the currency that circulates is of another nature (“Bad money”). Nevertheless, scholars such as Hayek and Rothbard argue contrapositive.

Hayek (

2008) reminds us that “we have never had the chance to see what would emerge from the market. The monopoly of the government of issuing money has not only deprived us of sound money but has also deprived us of the only process by which we can find out what would be good money.”

Hayek (

1976) argues that one unique type of money imposed by the state is violating the freedom of contract of citizens. He advocates for the denationalization of money; he establishes money a good that can be traded in a free market; hence that private entity should issue and regulate currencies.

Selgin (

2008) mentions that the private coinage of the UK in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries evicted the bad government money. The monopoly was based on the idea that the government monopoly currency itself is the problem and that government barriers to private currency should be removed.

Rothbard (

1990) argues that the government monopoly of dollar-creation cannot overcome all problems. A misapplication of Gresham’s Law leads to the fear that bad money would drive out good private currency. Still, Gresham’s Law only applies where fixed rates of exchange have been set and enforced by law. In a free market, sound currencies should flourish, and the bad will die off.

It can be emphasized that the rush for gold indicates the demand for good money driving out bad money in a time when the rule of authorities is weakened, or institutions failed; people need to bank on only a close community.

Bad money drives out good money, and the fact that money is a product of dual use, for most of the period, is neglected. Once people hoard currency, it is not currency anymore, and it turns into an investment. However, both are still recognized as monies. It transforms into a very liquid asset. When the institution of money fails, foreign money substitutes and circulates as domestic currency; dollarization is one of the cases when an economy’s currency fails both its function as a store of value and an instrument of exchange. Generally, local currency can survive monetary and currency issues, if the country is able to maintain the storage of value feature of the money. However, in the currency crisis, both features are tarnished and consequently, the country may replace the currency with a stable and universal alternative such as the US dollar. In this case, the foreign currency becomes a local currency since the supply of foreign currency is restricted and limited (a foreign entity owns it); it helps to stabilize the prices of goods and services priced with it. The official currency drives out the good one since it is the inferior money, which loses its value.

The main, the inflationary currency loses value since the government can print as it wishes; this money is a candidate to be disposed of. Turkey is a noticeable case. For the last two decades, it has been more common among shop owners in Turkey; to exchange their Turkish Lira to the US dollar for the next day. They would exchange the US dollar back to Lira the following day, a daily hedge against bad money, self-protection against the overnight surge of the exchange rate. In this case, the US dollar acts as local currency to the main currency while the quantity of supply of the US dollar is driven and provided by the business community; it bears a limited supply attribute to the Turkish Lira.

Fisher (

1934) and

Harper (

1948) document that around 400 clubs were organized in 30 states in the United States in the great depression time. As

Harper (

1948) explains, this movement began in the West and spread to various parts of the country, but by far the most considerable number of such organizations were found in California, Washington, Idaho, and Utah. At the time of crisis, people will choose a lesser risky asset.

Colacelli and Blackburn (

2009) indicate that the circulation of creditos (the complementary currency of the time) in Argentina was strongly correlated with shortages of the main currency, as it held valid on the growth of local ‘scrip’ currencies in the US depression of the 1930s (

Fisher 1934).

A Federal Reserve study (

Rolnick and Weber 1994) confirms that the average rate of inflation for commodity money (gold and silver) was about minus −0.5% per year as several different currencies were circulating, i.e., before the institution of the central bank whereas main currencies remain monopolies for central banks, showing that currency competition conveys specific monetary stability functions.

Principally, throughout history, three monetary policies are perceived while monetary regimes were observed.

Schumpeter (

1950) classifies them intelligibly. Schumpeter, as depicted in

Table 2, argues that monetary policy is the first and foremost tool in the hands of politics and monetary authorities.

The first category addresses the slow rate of monetary expansion; hence the growth rate of overall goods and services surpasses the rate of monetary expansion and usually leads to falling prices due to a shortage of the medium of exchange. In this regime, since money becomes a scarce resource, its value increases, and those who possess the funds benefit from the more substantial purchasing power of money. Wage-earners earn a wage, attain more purchasing power, and will benefit from the deflationary prices as well; complementary currencies like Gesell’s Worgl are classified as slow-growth monies. The Gesellian system of money follows the slow-growth money supply model.

The fast-growth monetary policy suggests a higher rate of monetary growth than the real economy. In this case, monetary authorities, particularly central banks, tend to increase the money supply to achieve certain objectives and mandates. In such a scenario, the growth of monetary assets is higher than the real rate of production of goods and services in the economy. Inflation ensued as the outcome of this policy; wage earners suffer due to the falling purchasing power of the money, and the saver suffers diminished savings. Inflationary and expansionary monetary policy benefits entrepreneurs as they will be paying back diminished debt and liability obligations.

The third policy follows a path of a stable regime for the money, whereas the economy expands or contracts. The purchasing power of money remains consistent and steady during a long period as the supply and demand for money moves according to the rate of production. Irving

Fisher (

1934) introduced the CPI and the measurement of price levels intending to achieve a standard of measurement to a stable price level among key goods and services.

The central question remains as to whether the relation between money supply, economic output, and the circulation of secondary currencies advocates and promotes the existing literature of dual and complementary currency.

4. Resilience and Crisis Mitigation

Originating from natural sciences, the term “resilience,” provides tools, methods, structures, and processes which lead and direct a phenomenon or organism to resist disruptive and mortal events and promote and foster stability in a holistic, ontological perspective. Manzini defines resilience as “the system’s capacity to cope with stress and failure without collapsing and, more importantly, learning from the experience” (

Manzini and Till 2015, p. 11).

Before the metal standard was established, in Europe and elsewhere, (

Innes 1913), there were large amounts of privately issued metal tokens in widespread use, and recent research had produced more evidence of the fact that the monetary systems before the gold standard were characterized by the coexistence of multiple public and private currencies (

Kuroda 2008;

Fantacci 2005). As history (

Oresme 1956) says, “Wherefore if there is not enough gold, money is also made of silver, and where these two metals do not exist or are insufficient, they must be alloyed or simple money be made of another metal, without alloy as was formerly the case with copper as Ovid tells in the first book of the Fasti saying: Men paid in copper once, they are now for gold, And the new money elbows out the old.” To Oresme money is an instrument of trade-in order to ease the trade and the economy does not necessarily require to be tied to a specific medium of exchange (

Oresme 1956).

Nevertheless, an alternative currency does not function in the same pattern when it enters different geographies.

Due to the size and domain of local and regional economies, every level would require a different approach. Local governments’ concern is focused on the shutdown of the business, and continuously of economic transactions and of the circulation of the instrument of trade. In times of crisis, complementary currencies tend to function more as a medium of exchange rather than a store of value. Since crises penetrate and act in a short time and sensitive horizons, any monetary provision should address timely-originated and more so liquidity-related challenges. Consequently, finding a solution will be meaningful if it is narrowed down to a certain and manageable geography. The reason such currencies address local issues is an indicator of this fact, and the case study of the Lewes pound demonstrates such demand (

Graugaard 2012).

As

Lucarelli and Gobbi (

2016) mentions, one of the consequences of the financial crisis is that currency and money is hoarded by middleware institutions, therefore it gives rise to a situation in which money is not spent and debts are not paid.

Local clearinghouses can act as stabilizers of the local economic circuit, which mainly eases and promotes the imbalance between lenders and borrowers. Complementary currencies facilitate to revive existing and under-utilized assets through the development of local networks of trust and local clearing houses (

Gomez 2018), and they lay the foundations for building stronger local and regional economies, which are more resilient and capable of embracing the effects of future financial crises. As a matter of fact, the medium of exchange property of this money develops a stabilizer force.

Another aspect of local currency is social connectivity and circuit-building functionality since they are a powerful tool for increasing local employment in local communities. As

Spano and Martin (

2018) proposed that if the complementary currency is tied and coupled with unemployment benefits, it provides a replacement for the efforts and labor absorbed by the community.

It was in 2001 when the Argentine government defaulted and the Peso, the currency, collapsed. A short on Peso resulted in the creation of three alternatives for the economy and people. These were the US dollar, the Patacon bond and the Credito complementary currency, which replaced the currency, in fact, alternative currencies, though the Argentine Peso remained for several years. Four different currencies (

Gomez 2018) at the same time (international dollar, national Peso, bond, and community currencies) circulated in Argentina’s economy. While the Argentine economy was hurt in general, it received an improvement and provincial public services were enhanced when local governments circulated local currencies backed by local taxes.

The last century offers a vast number of complementary currencies which act as coins and other forms of money such as the International Military Payment Certificates (

Gomez 2018), Obsidional and Military Banknotes, Banker´s Drafts, Liberty Bonds, Exchequers in the UK or US Treasury War Bonds, and the Schatzanweisungen (in German), also known as War Bonds (Kriegsanleihen), as

Gomez (

2018) mentions around 500 different complementary currencies circulated in the time of war, notably in Indonesia, Israel, Italy, and Hungary.

The historical role of complementary currency in times of crisis cannot be neglected.

5. Conclusions

Ever since the middle ages through the 19th century, merchants, artisans, restaurateurs and cafeterias have offered customers good nominated tokens as the currency of their trade; the capacity to tokenize the production plays a significant advertising and commercial function for the issuers, while it has been extended to the present day. In system engineering terms, it is called resilience.

One of the methods to achieve resilience is through diversity. Diversity creates an environment which prevents a system collapsing or breakdown over a single point of failure. The word currency derives from current and it relates to a circuit of actors within a network. Once this circuit has the capacity and backup structure in place, in times of circuit disconnect, another set of wirings benefit from continuing the operation of the network. In the economic system, this can be played by a secondary or complementary currency.

The argument remains credible whether complementary currency as a tool of and resilience and competition offers not only diversity but also a form of currency that circulates faster; therefore, it conveys extra goods and services and economic activities. Complementary currency in circulation represents economic activities performed by goods and services unaccounted for by the main currency in the economy. They represent and exhibit a segment of transactions in the real economy. Tokens, jetton and mereaux can express this portion of economic activities. Complementary currencies institute multiple equilibria in various layers of goods, products and services. It extends the argument further on multiple equilibria. It advances the studies on whether the complementary currency manifests mereau-like currency for barter transactions, while barter transactions accommodate countercyclical attributes in the economy. Therefore, a complementary currency can take up where the main currency comes short. It advances the demand for the complementary currency, extended to where the contraction of the official currency shrinks.

Money can be anything that is agreed upon within a network of exchange, even in a barter system. Complementary currency offers a counter instrument to inflationary currency; addresses social issues, inflation and crises at the macro-level of an economy.

A self-governing local credit and finance system can provide economical means and powerful incentives in comparison to the top-down, command and control and expensive methods of hierarchy and bureaucratic management, policing, prosecuting and punishment. The local credit issuance may open the door for international microcredit institutions if technology allows it. Complementary monetary systems emerge from a historical necessity within civil society to address community necessity.