Board-Gender Diversity, Family Ownership, and Dividend Announcement: Evidence from Asian Emerging Economies

Abstract

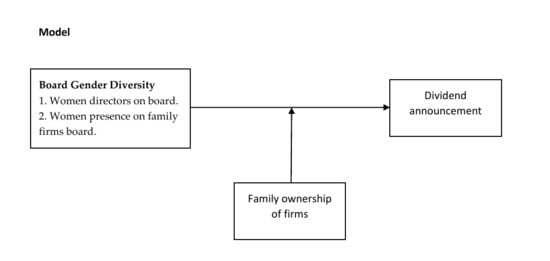

1. Introduction

2. Literature and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Literature

2.2. Empirical Literature

2.3. Hypotheses Development

2.3.1. Women Directors on Boards

2.3.2. Family Ownership and Board Gender-Diversity

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Context Overview

3.2. Sample

3.3. Variable Measurement

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

3.3.2. Independent Variables

3.3.3. Control Variables

3.4. Method of Analysis

4. Empirical Findings

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullah, Shamsul N., Ku Nor Izah Ku Ismail, and Lilac Nachum. 2016. Does having women on boards create value? The impact of societal perceptions and corporate governance in emerging markets. Strategic Management Journal 37: 466–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Renée B., and Daniel Ferreira. 2009. Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics 94: 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Renée B., and Patricia Funk. 2012. Beyond the glass ceiling: Does gender matter? Management Science 58: 219–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjaoud, Fodil, and Walid Ben-Amar. 2010. Corporate governance and dividend policy: Shareholders’ protection or expropriation? Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 37: 648–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, Kenneth R., and Amy K. Dittmar. 2012. The changing of the boards: The impact on firm valuation of mandated female board representation. Quarterly Journal of Economics 127: 137–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-dhamari, Redhwan, Ku Ismail, Ku Nor Izah, and Bakr Al-Gamrh. 2016. Board diversity and corporate payout policy: Do free cash flow and ownership concentration matter? Corporate Ownership and Control 14: 373–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazan, Andres, and Javier Suarez. 2003. Entrenchment and severance pay in optimal governance structures. Journal of Finance 58: 519–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najjar, Basil, and Erhan Kilincarslan. 2016. The effect of ownership structure on dividend policy: Evidence from Turkey. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 16: 135–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahahleh, Ayat S. 2017. Corporate governance quality, board gender diversity and corporate dividend policy: Evidence from Jordan. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal 11: 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Ronald C., and David M. Reeb. 2003. Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. The Journal of Finance 58: 1301–28. [Google Scholar]

- Arano, Kathleen, Carl Parker, and Rory Terry. 2010. Gender-based risk aversion and retirement asset allocation. Economic Inquiry 48: 147–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attig, Najah, Narjess Boubakri, Sadok El Ghoul, and Omrane Guedhami. 2016. The global financial crisis, family control, and dividend policy. Financial Management 45: 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baack, Jane, Norma Carr-Ruffino, and Monique Pelletier. 1993. Making it to the top: Specific leadership skills. Women in Management Review 8: 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Suman, Mark Humphery-Jenner, and Vikram Nanda. 2013. CEO Overconfidence and Share Repurchases. Paper presented at 26th Australasian Finance and Banking Conference 2013, Sydney, Australia, December 17–19. UNSW Australian School of Business Research Paper No. 2013 BFIN 04, Avai. Unpublished Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Bear, Stephen, Noushi Rahman, and Corinne Post. 2010. The Impact of Board Diversity and Gender Composition on Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Reputation. Journal of Business Ethics 97: 207–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneish, Messod D. 2001. Earnings management: A perspective. Managerial Finance 27: 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, Samuel, and Pallab Kumar Biswas. 2017. Board Gender Composition, Dividend Policy and Cost of Debt: The Implications of CEO Duality. Paper presented at 8th Conference on Financial Markets and Corporate Governance (FMCG), Wellington, New Zealand, April 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Nasr, Hamdi. 2015. Government ownership and dividend policy: Evidence from newly privatized firms. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 42: 665–704. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, Richard A., Susan M. Bosco, and Katie M. Vassill. 2006. Does female representation on boards of directors associate with Fortune’s “100 Best Companies to Work For” list? Business & Society 45: 235–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, Sudipto. 1979. Imperfect information, dividend policy, and “the bird in the hand” fallacy. Bell Journal of Economics 10: 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, Ritu. 2007. Road blocks in enhancing competitiveness in family-owned business in India. Available online: https://www.citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.574.8570&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 14 September 2019).

- Bhojraj, Sanjeev, and Partha Sengupta. 2003. Effect of corporate governance on bond ratings and yields: The role of institutional investors and outside directors. The Journal of Business 76: 455–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Mazagatos, Virginia, Esther de Quevedo-Puente, and Luis A. Castrillo. 2007. The trade-off between financial resources and agency costs in the family business: An exploratory study. Family Business Review 20: 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøhren, Øyvind, and R. Øystein Strøm. 2007. Aligned, Informed, and Decisive: Characteristics of ValueCreating Boards. EFA 2007 Ljubljana Meetings Paper. Available online: http://ssrn.com/abstract=966407 (accessed on 9 March 2019).

- Boulouta, Ioanna. 2013. Hidden Connections: The Link between Board Gender Diversity and Corporate Social Performance. Journal of Business Ethics 113: 185–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, Stephen, Andrew Millington, and Stephen Pavelin. 2007. Gender and Ethnic Diversity among UK Corporate Boards. Corporate Governance: An International Review 15: 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broome, Lissa L., John M. Conley, and Kimberly D. Krawiec. 2011. Dangerous categories: Narratives of corporate board diversity. Duke Working Paper Series 2/25/2011 89: 759. [Google Scholar]

- Byoun, Soku, Kiyoung Chang, and Young Sang Kim. 2016. Does corporate board diversity affect corporate payout policy? Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies 45: 48–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Kevin, and Antonio Mínguez Vera. 2007. The Influence of Gender on Spanish Boards of Directors: An Empirical Analysis. IVIE Working Paper, WP-EC 2007-08. València: IVIE. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Kevin, and Antonio Mínguez Vera. 2008. Gender Diversity in the Boardroom and Firm Financial Performance. Journal of Business Ethics 83: 435–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Kevin, and Antonio Minguez Vera. 2010. Female board appointments and firm valuation: Short and long-term effects. Journal of Management & Governance 14: 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, David A., Betty J. Simkins, and W. Gary Simpson. 2003. Corporate Governance, Board Diversity, and firm value. Financial Review 38: 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, David A., Frank D’Souza, Betty J. Simkins, and W. Gray Simpson. 2010. The gender and ethnic diversity of US boards and board committees and firm financial performance. Corporate Governance: An International Review 18: 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jie, Woon Sau Leung, and Marc Goergen. 2017. The impact of board gender composition on dividend payouts. Journal of Corporate Finance 43: 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Eugene C. M., and Stephen M. Courtenay. 2006. Board composition, regulatory regime and voluntary disclosure. The International Journal of Accounting 41: 262–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Dong-Sung, and Jootae Kim. 2007. Outside directors, ownership structure and firm profitability in Korea. Corporate Governance: An International Review 15: 239–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Sue Campbell. 2000. Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Human Relations 53: 747–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, Taylor, Jr. 1991. The multicultural organization. Academy of Management Perspectives 5: 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, Catherine M., S. Trevis Certo, and Dan R. Dalton. 1999. A Decade of Corporate Women: Some Progress in the Board-room, None in the Executive Suite. Strategic Management Journal 20: 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cabo, Ruth Mateos, Ricardo Gimeno, and María J. Nieto. 2012. Gender Diversity on European Banks’ Boards of Directors. Journal of Business Ethics 109: 145–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte Report on Women on Board. 2019. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/about-deloitte/press-releases/deloitte-global-latest-women-in-the-boardroom-report-highlights-slow-progress-for-gender-diversity.html (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Deng, Xin. 2016. China: A Case Study of Father–Daughter Succession in China. Father-Daughter Succession in Family Business, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, Sanjay, Anand M. Goel, and Keith M. Howe. 2010. CEO overconfidence and dividend policy. Journal of Financial Intermediation 22: 440–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezsö, Cristian L., and David Gaddis Ross. 2012. Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation. Strategic Management Journal 33: 1072–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanani, Alpa. 2005. Corporate dividend policy: The views of British financial managers. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 32: 1625–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djan, George Ohene, S. Zehou, and Jonas Bawuah. 2017. Board Gender Diversity and Dividend Policy in SMEs: Moderating Role of Capital Stucture in Emerging Market. Journal of Research in Business Economoics and Management 9: 1667–76. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, Michael, and Zakaria Ali Aribi. 2013. Female directors and UK company acquisitiveness. International Review of Financial Analysis 29: 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, Colette. 1998. Women’s Pathways to Participation and Leadership in Family-owned Firms. Family Business Review 11: 219–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Blair T. Johnson. 1990. Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 108: 233–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmagrhi, Mohammed H., Collins G. Ntim, Richard M. Crossley, John Kalimilo Malagila, Samuel Fosu, and Tien V. Vu. 2017. Corporate governance and dividend pay-out policy in UK listed SMEs: The effects of corporate board characteristics. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management 25: 459–83. [Google Scholar]

- Elstad, Beate, and Gro Ladegard. 2012. Women on corporate boards: Key influencers or tokens? Journal of Management & Governance 16: 595–615. [Google Scholar]

- Ely, Robin J., and Debra E. Meyerson. 2000. Advancing gender equity in organizations: The challenge and importance of maintaining a gender narrative. Organization 7: 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, Niclas L., James D. Werbel, and Charles B. Shrader. 2003. Board of Director Diversity and Firm Financial Performance. Corporate Governance: An International Review 11: 102–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Mark. 2005. Coutts 2005 Family Business Survey. Available online: http://www.Coutts.com/files/pdf/family-business-survey-master.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Faccio, Mara, Larry H. P. Lang, and Leslie Young. 2001. Dividends and expropriation. American Economic Review 91: 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Michael C. Jensen. 1983. Separation of Ownership and Control. Journal of Law and Economics 26: 301–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, Michael, Jin Gao, Jianghua Shen, and Yuanyuan Zhang. 2016. Institutional stock ownership and firms’ cash dividend policies: Evidence from China. Journal of Banking & Finance 65: 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons, Stacey R. 2012. Women on boards of directors: Why skirts in seats aren’t enough. Business Horizon 55: 557–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondas, Nanette, and Susan Sassalos. 2000. A different voice in the boardroom: How the presence of women directors affects board influence over management. Global Focus 12: 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Bill, Iftekhar Hasan, Jong Chool Park, and Qiang Wu. 2014. Gender differences in financial reporting decision making: Evidence from accounting conservatism. Contemporary Accounting Research 32: 1285–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francoeur, Claude, Réal Labelle, and Bernard Sinclair-Desgagné. 2008. Gender diversity in corporate governance and top management. Journal of Business Ethics 81: 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, Ferdinand A., Bin Srinidhi, and Anthony C. Ng. 2011. Does board gender diversity improve the informativeness of stock prices? Journal of Accounting and Economics 51: 314–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyapong, Ernest, Ammad Ahmed, Collins G. Ntim, and Muhammad Nadeem. 2019. Board gender diversity and dividend policy in Australian listed firms: the effect of ownership concentration. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, Arunima, and Mehul Raithatha. 2017. Do compositions of board and audit committee improve financial disclosures? International Journal of Organizational Analysis 25: 251–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardies, Kris, Ann Jorissen, and Parichart Maneemai. 2014. On the presence and absence of CEO gender effects on management control choices: An empirical investigation. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2496613 (accessed on 21 September 2019). [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, Maretno A., Indrarini Laksmana, and Ya-wen Yang. 2014. Board Diversity and Corporate Risk Taking. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2412634 (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- Hillman, Amy J., Christine Shropshire, and Albert A. Cannella. 2007. Organizational predictors of women on corporate boards. Academy of Management Journal 50: 941–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, Sander, Hessel Oosterbeek, and Mirjam Van Praag. 2013. The impact of gender diversity on the performance of business teams: Evidence from a field experiment. Management Science 59: 1514–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Hwa-Hsien, and Chloe Yu-Hsuan Wu. 2014. Board composition, grey directors and corporate failure in the UK. The British Accounting Review 46: 215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Helen Wei, On Kit Tam, and Monica Guo-Sze Tan. 2010. Internal governance mechanisms and firm performance in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 27: 727–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingley, Coral, and Nicholas Van Der Walt. 2005. Do board processes influence director and board performance? Statutory and performance implications. Corporate Governance: An International Review 13: 632–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Maimunah, and Mariani Ibrahim. 2008. Barriers to career progression faced by women: Evidence from a Malaysian multinational oil company. Gender in Management: An International Journal 23: 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittonen, Kim, Johanna Miettinen, and Sami Vähämaa. 2010. Does female representation on audit committees affect audit fees? Quarterly Journal of Finance and Accounting 49: 113–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Michael C. 1986. Agency cost of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. The American Economic Review 76: 323–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jizi, Mohammad. Issam, Aly Salama, Robert Dixon, and Rebecca Stratling. 2014. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from the US banking sector. Journal of Business Ethics 125: 601–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonge, Alice. 2014. The Glass Ceiling that Refuses to Break: Women Directors on the Boards of Listed Firms in China and India. Women Studies International Forum. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.01.008 (accessed on 18 September 2019).

- Joshi, Aparna, Hui Liao, and Susan E. Jackson. 2006. Cross-level effects of workplace diversity on sales performance and pay. Academy of Management Journal 49: 459–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellerman, Barbara, and Deborah L. Rhode, eds. 2007. Women and Leadership: The State of Play and Strategies for Change. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Klasen, Stephan, and Francesca Lamanna. 2009. The impact of gender inequality in education and employment on economic growth: New evidence for a panel of countries. Feminist Economics 15: 91–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijn, Sander J. J., Roman Kräussl, and Andre Lucas. 2011. Blockholder dispersion and firm value. Journal of Corporate Finance 17: 1330–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koropp, Christian, Franz W. Kellermanns, Dietmar Grichnik, and Laura Stanley. 2014. Financial decision making in family firms: An adaptation of the theory of planned behavior. Family Business Review 27: 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Vicki W., and Alision M. Konrad. 2007. Critical Mass on Corporate Boards. The Wellesley Centers for Women. Wellesley, Massachussets. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, Gopal V., and Linda M. Parsons. 2008. Getting to the bottom line: An exploration of gender and earnings quality. Journal of Business Ethics 78: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtulus, Fidan Ana, and Donald Tomaskovic-Devey. 2012. Do female top managers help women to advance? A panel study using EEO-1 records. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 639: 173–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, Rafael, Forencio Lopez-de-Silanes Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. 1998. Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy 106: 1113–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Kevin C. K., Heibatollah Sami, and Haiyan Zhou. 2012. The role of cross-listing foreign ownership and state ownership in dividend policy in an emerging market. China Journal of Accounting Research 5: 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yuen Ting. 2015. A Comparative Analysis of China and India: Ancient Patriarchy, Women’s Liberation, and Contemporary Gender Equity Education. Journal of Asian and African Studies 14: 134–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, Maurice D., Kai Li, and Feng Zhang. 2011. Men are from Mars, Women Are from Venus: Gender and Mergers and Acquisitions. Women are from Venus: Gender and Mergers and Acquisitions. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1785812 (accessed on 21 September 2019).

- Liu, Yu, Zuobao Wei, and Feixue Xie. 2013. Do Women Directors Improve Firm Performance in China? Journal of Corporate Finance 28: 169–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, Amy, Matilde Salganicoff, and Barbara Hollander. 1985. Women in family business: An untapped resource. SAM Advanced Management Journal 50: 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadeo, Jyoti D., Teerooven Soobaroyen, and Vanisha Oogarah Hanuman. 2012. Board Composition and Financial Performance: Uncovering the Effects of Diversity in an Emerging Economy. Journal of Business Ethics 105: 375–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahérault, Loïc. 2000. The influence of going public on investment policy: An empirical study of French family-owned businesses. Family Business Review 13: 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, Joana, Janneke Plantenga, and Chantal Remery. 2010. Gender Diversity and Firm Performance: Evidence from Dutch and Danish Boardrooms. Discussion Paper. Utrecht: University of Utrecht, Utrecht School of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness, Paul B., Kevin C. K. Lam, and João Paulo Vieito. 2015. Gender and other major board characteristics in China: Explaining corporate dividend policy and governance. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 32: 989–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, Paul B., João Paulo Vieito, and Mingzhu Wang. 2017. The role of board gender and foreign ownership in the CSR performance of Chinese listed firms. Journal of Corporate Finance 42: 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Merton H., and Franco Modigliani. 1961. Dividend policy, growth, and the valuation of shares. The Journal of Business 34: 411–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Danny, Isabelle Le Breton-Miller, Richard H. Lester, and Albert A. Cannella, Jr. 2007. Are family firms really superior performers? Journal of Corporate Finance 13: 829–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A. Morrison, Randall P. White, and Ellen Van Velsor. 1987. Breaking The Glass Ceiling: Can Women Reach the Top of America’s Largest Corporations? London: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrum, Muhammad. 2013. The Influence of Ownership Structure, Corporate Governance, Investment Decision, Financial Decision and Dividend Policy on the Value of the Firm Manufacturing Companies Listed on The Indonesian Stock Exchange. Journal Managerial 1. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2286074 (accessed on 18 September 2019).

- Nielsen, Sabina, and Morten Huse. 2010. The Contribution of Women on Boards of Directors: Going Beyond the Surface. Corporate Governance: An International Review 18: 136–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmberg, Johanna, Johan Eklund, and Daniel Wiberg. 2009. Ownership structure, board /composition and investment performance. Corporate Ownership and Control 7: 117. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides, Konstantinos V., and Adrian Furnham. 2006. The role of trait emotional intelligence in a gender-specific model of organizational variables. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 36: 552–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, Jeffrey, and Gerald R. Salancik. 1978. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Gary N. 1990. One more time: Do female and male managers differ? Academy of Management Executive 4: 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V. Kanti, Gurramkonda M. Naidu, B. Kinnera Murthy, Doan E. Winkel, and Kyle Ehrhardt. 2013. Women entrepreneurs and business venture growth: an examination of the influence of human and social capital resources in an Indian context. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 26: 341–364. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna, P. Krishna. 2014. Firm-level governance quality and dividend decisions: Evidence from India. International Journal of Corporate Governance 5: 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prencipe, Annalisa, Sasson Bar-Yosef, Pietro Mazzola, and Lorenzo Pozza. 2011. Income smoothing in family-controlled companies: Evidence from Italy. Corporate Governance: An International Review 19: 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, María Consuelo, and Inmaculada Bel-Oms. 2015. The board of directors and dividend policy: The effect of gender diversity. Industrial and Corporate Change 25: 523–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, Maria Consuelo, Inmaculada Bel-Oms, and Gustau Olcina-Sempere. 2016. Corporate governance, female directors and quality of financial information. Business Ethics: A European Review 25: 363–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, Kavil, and Navneet Bhatnagar. 2012. Challenges faced by family businesses in India. Available online: https://www.isb.edu/sites/default/files/challengesfacedbyindian_1.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Ramli, Nathasa Mazna. 2010. Ownership structure and dividend policy: Evidence from Malaysian companies. International Review of Business Research Papers 6: 170–80. [Google Scholar]

- Randøy, Trond, Steen Thomsen, and Lars Oxelheim. 2006. A Nordic perspective on corporate board diversity. Age 390: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Renneboog, Luc, and Peter G. Szilagyi. 2015. How relevant is dividend policy under low shareholder protection? Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1042443115000074 (accessed on 16 September 2019).

- Richard, Orlando C., Tim Barnett, Sean Dwyer, and Ken Chadwick. 2004. Cultural diversity in management, firm performance, and the moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation dimensions. Academy of Management Journal 47: 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Caspar. 2007. Does female board representation influence firm performance? The Danish evidence. Corporate Governance: An International Review 15: 404–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Barbadillo, Emiliano, Estíbaliz Biedma-López, and Nieves Gómez-Aguilar. 2007. Managerial dominance and Audit Committee independence in Spanish Corporate Governance. Journal of Management and Governance 11: 331–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, Abubakr, and Muhammad Sameer. 2017. Impact of board gender diversity on dividend payments: Evidence from some emerging economies. International Business Review 26: 1100–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanan, Neeti Khetarpal. 2019. Impact of board characteristics on firm dividends: Evidence from India. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 19: 1204–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenger, Michael H., David D. Wood, and Ahmad Tashakori. 1989. Board of director composition, shareholder wealth, and dividend policy. Journal of Management 15: 457–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia-Atmaja, Lukas. 2010. Dividend and debt policies of family controlled firms: The impact of board independence. International Journal of Managerial Finance 6: 128–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vineeta. 2011. Independent directors and the propensity to pay dividends. Journal of Corporate Finance 17: 1001–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert W. Vishny. 1986. Large shareholders and corporate control. The Journal of Political Economy 94: 461–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnemans, Joep H., Frans Van Dijk, and Frans van Winden. 2000. Group Formation in a Public Good Experiment (No. 99-093/1). Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper. Amsterdam: Tinbergen Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Srinidhi, Bin, Ferdinand A. Gul, and Judy Tsui. 2011. Female directors and earnings quality. Contemporary Accounting Research 28: 1610–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Zhong-Qin, Hung-Gay Fung, Deng-Shi Huang, and Chung-Hua Shen. 2013. Cash dividends, expropriation, and political connections: Evidence from China. International Review of Economics & Finance 29: 260–72. [Google Scholar]

- Terjesen, Siri, Ruth Sealy, and Val Singh. 2009. Women directors on corporate boards: A review and research agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review 17: 320–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchia, Mariateresa, Andrea Calabrò, and Morten Huse. 2011. Women directors on corporate boards: From tokenism to critical mass. Journal of Business Ethics 102: 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Essen, Marc, J. Hans van Oosterhout, and Michael Carney. 2012. Corporate boards and the performance of Asian firms: A meta-analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 29: 873–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Essen, Marc, Michael Carney, Eric R. Gedajlovic, and Pursey P. Heugens. 2015. How does family control influence firm strategy and performance? A meta-analysis of US publicly listed firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review 23: 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Pelt, Thomas. 2013. The Effect of Board Characteristics on Dividend Policy. Working Paper. Tilburg: Tilburg School of Economics and Management, Department of Finance, Tilburg University, pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, Aila. 2012. Women on the boards of listed companies: Evidence from Finland. Journal of Management & Governance 16: 571–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Dominic, and Roopa Purushothaman. 2003. Dreaming with BRICs: The path to 2050. Goldman Sachs Global Economics Paper 99: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey F. 2002. Econometric Analysis of Cross-Section and Panel Data. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. 2018. Global Gender Gap Report of 2018. Geneva: World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-gender-gap-report-2018 (accessed on 14 September 2019).

- World Trade Organization. 2019. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/anrep19_e.htm (accessed on 14 September 2019).

- Yan, Jun, and Ritch L. Sorenson. 2004. The Influence of Confucian Ideology on Conflict in Chinese Family Business. Cross Cultural Management 4: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarram, Subba Reddy, and Brian Dollery. 2015. Corporate governance and financial policies: Influence of board characteristics on the dividend policy of Australian firms. Managerial Finance 41: 267–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Dezhu, Jie Deng, Yi Liu, Samuel H. Szewczyk, and Xiao Chen. 2019. Does board gender diversity increase dividend payouts? Analysis of global evidence. Journal of Corporate Finance 58: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, Toru, and Abdul A. Rasheed. 2010. Family control and ownership monitoring in family-controlled firms in Japan. Journal of Management Studies 47: 274–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Haiyan. 2008. Corporate governance and dividend policy: A comparison of Chinese firms listed in Hong Kong and in the Mainland. China Economic Review 19: 437–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Cox (1991) | The results indicate that board gender diversity brings cost to an organization in the shape of communication and professional conflicts, which affect the decision-making process of board negatively. |

| Richard et al. (2004) | Board gender diversity increases intra-group conflicts, which affect firms’ decision-making processes negatively. |

| Rose (2007) | Results suggest that board gender diversity does not create any influence on firm performance. |

| Francoeur et al. (2008) | The results suggest that gender diversity on boards positively affect firm value. |

| McGuinness et al. (2017) | The results suggest that women on boards enhance the social performance of the firm. |

| Nasrum (2013) | Ownership structure and corporate governance have a positive influence on dividend policy and firm value. |

| Van Essen et al. (2015) | Diversification, internationalization, and financing strategies positively mediate the performance of family firms, but after the first generation, performance of family firms drops due to conventional patterns of strategic decision-making. |

| Haldar and Raithatha (2017) | The results of the study explain that the board of directors, including executive and non-executive directors, influence financial strategies of firms positively, and that audit committee plays a crucial role in increasing the effectiveness of decisions of firms. |

| Chen et al. (2017) | The results suggest that female directors pay high dividends in firms, whereas the governance system is weak and is used as a governance device. |

| McGuinness et al. (2015) | The results of the study show that independent women directors have limited influence on dividend payout, but that this impact is high and positive in firms where state investment is high. |

| Campbell and Vera (2010) | The results of the study suggest that announcement of appointment of women on boards increases the value of the firm in the long run, and that the stock market reacts positively on the appointment of women in the short run. |

| Campbell and Vera (2007) | The results of the study suggest that the relationship between women on boards and firm value is insignificant. |

| Al-dhamari et al. (2016) | The results of the study suggest that women on boards positively influence the dividend policy of firms, but only when firms have a high percentage of free cash flow. |

| Adjaoud and Ben-Amar (2010) | The results of the study suggest that firms with strong corporate governance practice positively influence the firm dividend payout policy, but that there is a negative relationship between the dividend policy and the level of firm risk. |

| Al-Rahahleh (2017) | The results of the study suggest that board gender diversity has a positive impact on the dividend policy of a firm. |

| Gyapong et al. (2019) | The results of the study suggest that female directors on boards positively influence the dividend policy of firms. This association of women and dividend policy is strong where the percentage of women on boards is high, and that the association is negative when ownership concentration is high. |

| Pucheta-Martínez and Bel-Oms (2015) | The findings of the research suggest that percentage of women and shares held by women are positively associated with dividend policy, but that institutional female directors have a negative impact on dividend policy, whereas independent and executive women have no effect on the dividend policies of firms. |

| Djan et al. (2017) | The results suggest that capital structure as an interactive term has insignificant impact on dividend policy. |

| Elmagrhi et al. (2017) | The findings of the study suggest that board gender diversity has a negative impact on the dividend policy of the firm, whereas audit committee and board size have a positive impact on the dividend policy of a firm. |

| Sanan (2019) | The results of the study suggest that percentage of female directors on boards have a negative effect on dividend policy, and that firms with strong corporate governance practices pay low dividends. |

| Ye et al. (2019) | The results of the study show that board gender diversity facilitates the corporate governance practice and promotes dividend policy. Institutional environments weaken the role of gender diversity on dividend policy, and relationship between gender diversity and dividend policy is strong when females have ownership in a firm. |

| Attig et al. (2016) | The findings suggests that family ownership has a negative impact on the dividend policies of firms. |

| Benjamin and Biswas (2017) | The results suggest that board gender diversity has a positive impact on the dividend policies of firms, but that the positive relationship only exists in the firms without CEO duality. |

| Setia-Atmaja (2010) | The results suggest that high investor protection pressurizes controlling shareholders to pay more dividends. |

| No. of Females on Firms Board | China | Malaysia | India | Pakistan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition of Board | Frequency: No. of Companies (%) | |||

| Entire sample | ||||

| 0 female directors | 167 (33.4%) | 77 (15.4%) | 50 (10%) | 245 (49%) |

| 1 female director | 141 (28.2%) | 126 (25.2%) | 167 (33.4%) | 132 (26.4%) |

| 2 female directors | 77 (15.4%) | 105 (21%) | 133 (26.6%) | 63 (12.6%) |

| 3 female directors | 40 (8%) | 6 (15.2%) | 83 (16.6%) | 39 (7.8%) |

| More than 3 female directors | 75 (15%) | 116 (23.2%) | 67 (13.4%) | 21 (4.2%) |

| Total | 500 (100%) | 500 (100%) | 500 (100%) | 500 (100%) |

| No. of Females on Family Firms Board | China | Malaysia | India | Pakistan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition of Board Entire Sample | Frequency: No. of Companies (%) | |||

| 0 female directors | 25 (21%) | 45 (12.7%) | 6 (2.6%) | 57 (48.7%) |

| 1 female director | 42 (35%) | 85 (24%) | 84 (36.3%) | 37 (31.6%) |

| 2 female director | 23 (19%) | 78 (22.1%) | 60 (25.8%) | 12 (10.3%) |

| 3 female directors | 6 (5%) | 56 (15.9%) | 47 (20.3%) | 8 (6.9%) |

| More than 3 female directors | 23 (19%) | 89 (25.2%) | 34 (15%) | 3 (2.5%) |

| Total | 119 (100%) | 353 (100%) | 231 (100%) | 117 (100%) |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dividend announcement | 0.69 | 0.47 | - | |||||||||

| Female presence | 0.77 | 0.41 | 0.04 *** | - | ||||||||

| Family presence | 0.43 | 0.49 | −0.02 * | −0.04 *** | - | |||||||

| Financial leverage | 89.96 | 134.54 | −0.07 *** | 0.01 * | 0.04 *** | - | ||||||

| Return on assets | 6.78 | 9.93 | 0.29 *** | 0.00 | −0.04 *** | −0.20 *** | - | |||||

| Liquidity | 1.21 | 1.63 | 0.053 *** | −0.00 | −0.03 *** | −0.18 *** | 0.17 *** | - | ||||

| Firm size | 6.31 | 2.12 | 0.18 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.19 *** | −0.04 *** | −0.06 *** | - | |||

| Board size | 2.89 | 0.54 | 0.06 *** | 0.18 *** | −0.08 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.04 *** | −0.04 *** | 0.21 *** | - | ||

| % independent women on board | 1.51 | 3.12 | 0.06 *** | 0.22 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.03 ** | 0.06 *** | 0.06 *** | 0.01 | 0.06 *** | - | |

| % executive women on board | 9.20 | 8.96 | 0.01 | 0.47 *** | −0.06 *** | −0.04 *** | 0.00 | 0.05 *** | −0.05 *** | −0.16 *** | 0.332 *** | 1 |

| Variables | Mean for Firm without Female Directors | Mean for Firm with Female Directors | t-Stats |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dividend announcement | 0.47 | 0.638 | −0.167 * |

| 2. Family presence | 0.48 | 0.421 | 0.062 * |

| 3. % women on board | 1.04 | 11.18 | −10.14 * |

| 4. % independent women on board | 0.17 | 1.90 | −1.72 * |

| 5. Board size | 2.69 | 3.01 | −0.31 * |

| 6. Firm size | 5.54 | 6.80 | −1.26 |

| 7. Return on assets | 6.41 | 6.43 | −0.02 * |

| 8. Liquidity | 1.20 | 1.19 | 0.01 * |

| 9. Financial leverage | 79.27 | 88.70 | −9.42 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female presence | −0.0714 * | −0.0724 * | −0.0251 |

| (0.0396) | (0.0396) | (0.0445) | |

| Family presence | −0.0540 * | 0.0190 | |

| (0.0296) | (0.0432) | ||

| Female presence × family presence | −0.108 ** | ||

| (0.0465) | |||

| Financial leverage | −0.000490 *** | −0.000489 *** | −0.000488 *** |

| (0.000103) | (0.000103) | (0.000103) | |

| Return on assets | 0.0518 *** | 0.0519 *** | 0.0520 *** |

| (0.00180) | (0.00181) | (0.00181) | |

| Liquidity | 0.000134 | 0.000149 | 0.000182 |

| (0.00824) | (0.00823) | (0.00824) | |

| Firm size | 0.150 *** | 0.150 *** | 0.150 *** |

| (0.0103) | (0.0103) | (0.0103) | |

| Board size | −0.000650 | −0.000603 | −0.000527 |

| (0.00142) | (0.00142) | (0.00142) | |

| % of independent women on board | 0.00894 * | 0.00895 * | 0.00900 * |

| (0.00504) | (0.00504) | (0.00505) | |

| % of executive women on board | 0.00382 ** | 0.00383 ** | 0.00394 ** |

| (0.00192) | (0.00192) | (0.00192) | |

| Constant | −0.872 *** | −0.835 *** | −0.863 *** |

| (0.0910) | (0.0934) | (0.0942) | |

| Observations | 10,707 | 10,707 | 10,707 |

| Likelihood ratio chi2 | 1677.61 | 1680.93 | 1686.33 |

| Probability > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1266 | 0.1269 | 0.1273 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mustafa, A.; Saeed, A.; Awais, M.; Aziz, S. Board-Gender Diversity, Family Ownership, and Dividend Announcement: Evidence from Asian Emerging Economies. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13040062

Mustafa A, Saeed A, Awais M, Aziz S. Board-Gender Diversity, Family Ownership, and Dividend Announcement: Evidence from Asian Emerging Economies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2020; 13(4):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13040062

Chicago/Turabian StyleMustafa, Adeel, Abubakr Saeed, Muhammad Awais, and Shahab Aziz. 2020. "Board-Gender Diversity, Family Ownership, and Dividend Announcement: Evidence from Asian Emerging Economies" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13, no. 4: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13040062

APA StyleMustafa, A., Saeed, A., Awais, M., & Aziz, S. (2020). Board-Gender Diversity, Family Ownership, and Dividend Announcement: Evidence from Asian Emerging Economies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(4), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13040062