Liquidity-Saving through Obligation-Clearing and Mutual Credit: An Effective Monetary Innovation for SMEs in Times of Crisis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

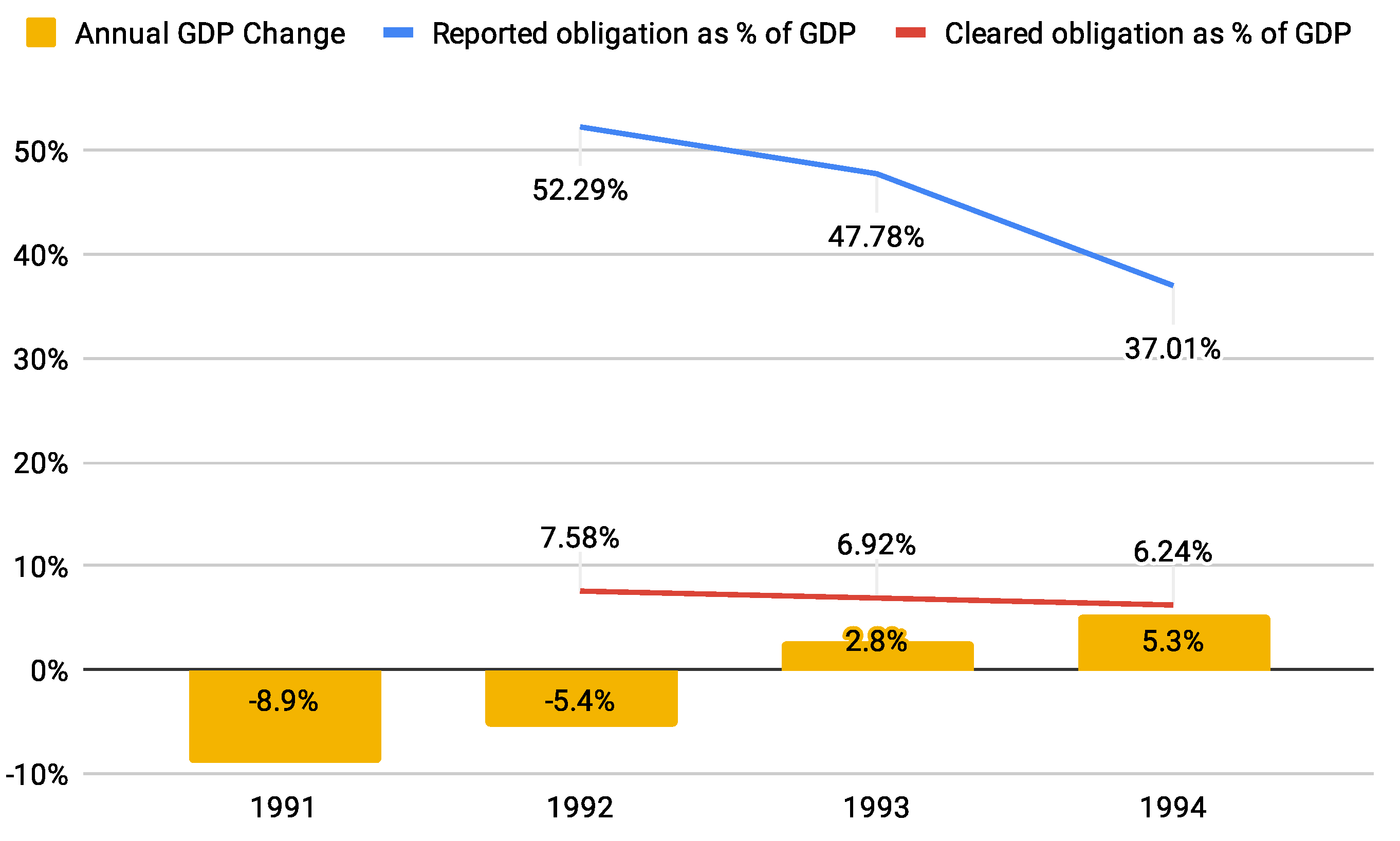

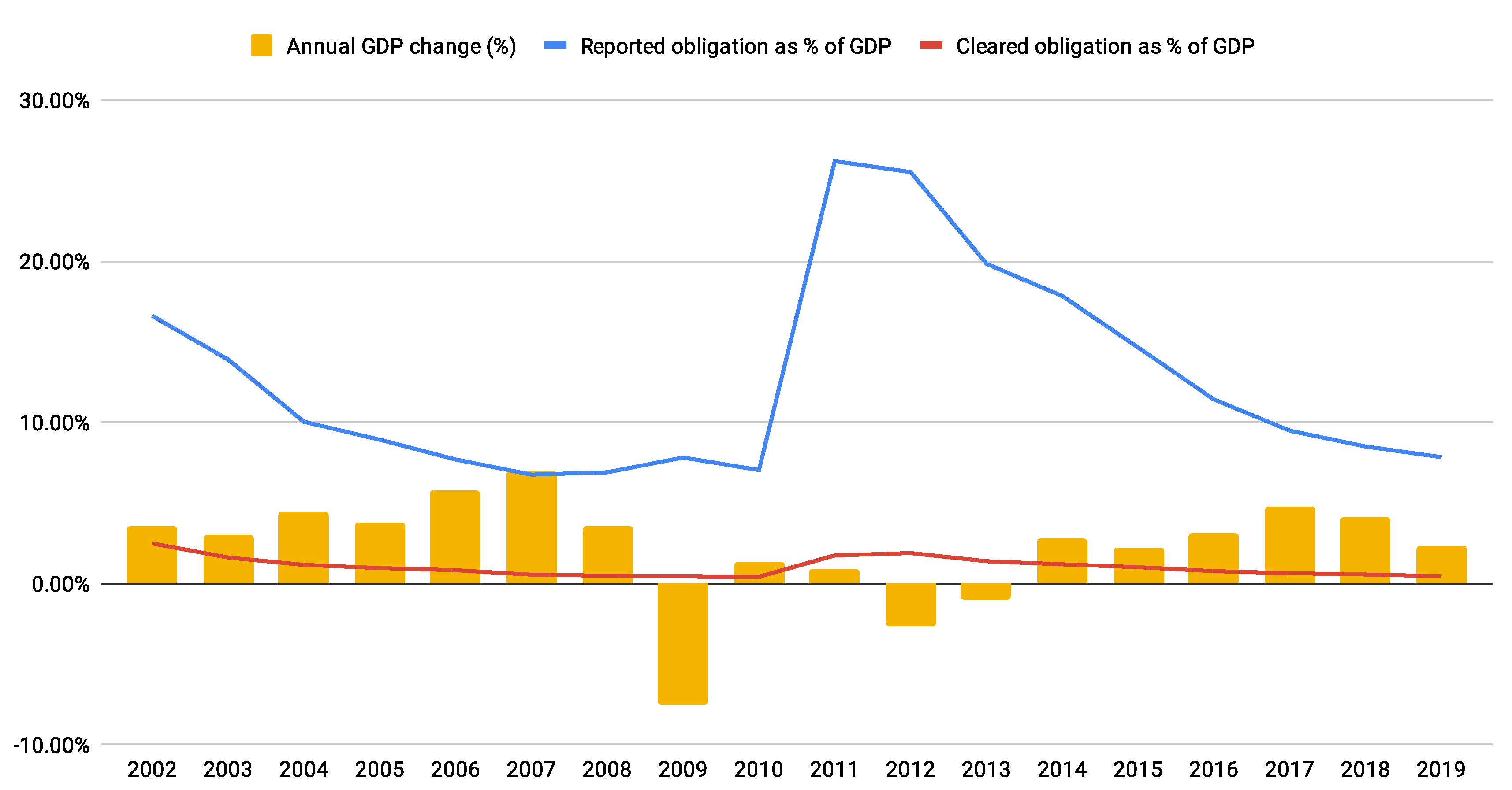

1.2. History and Context

1.3. Research Hypothesis

The research hypothesis is that obligation-clearing can potentially have a major impact in terms of liquidity-saving when measured as a fraction of national GDP, where ‘major’ means >10% and ‘potentially’ refers not to the efficacy of the algorithm but to the level of participation by firms.

2. Results

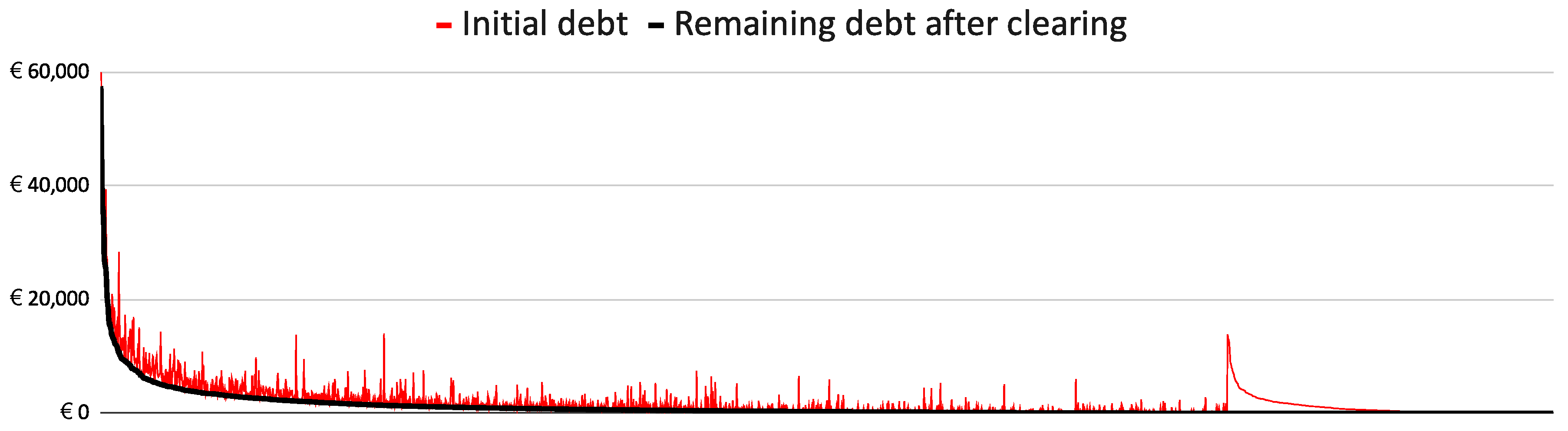

2.1. Quantitative Analysis with Real Invoice Data

- 3199 firms

- 138,378 transactions and

- 31,025,977.97 EUR total value of transactions.4

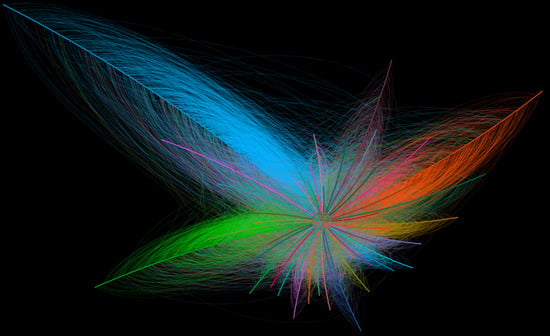

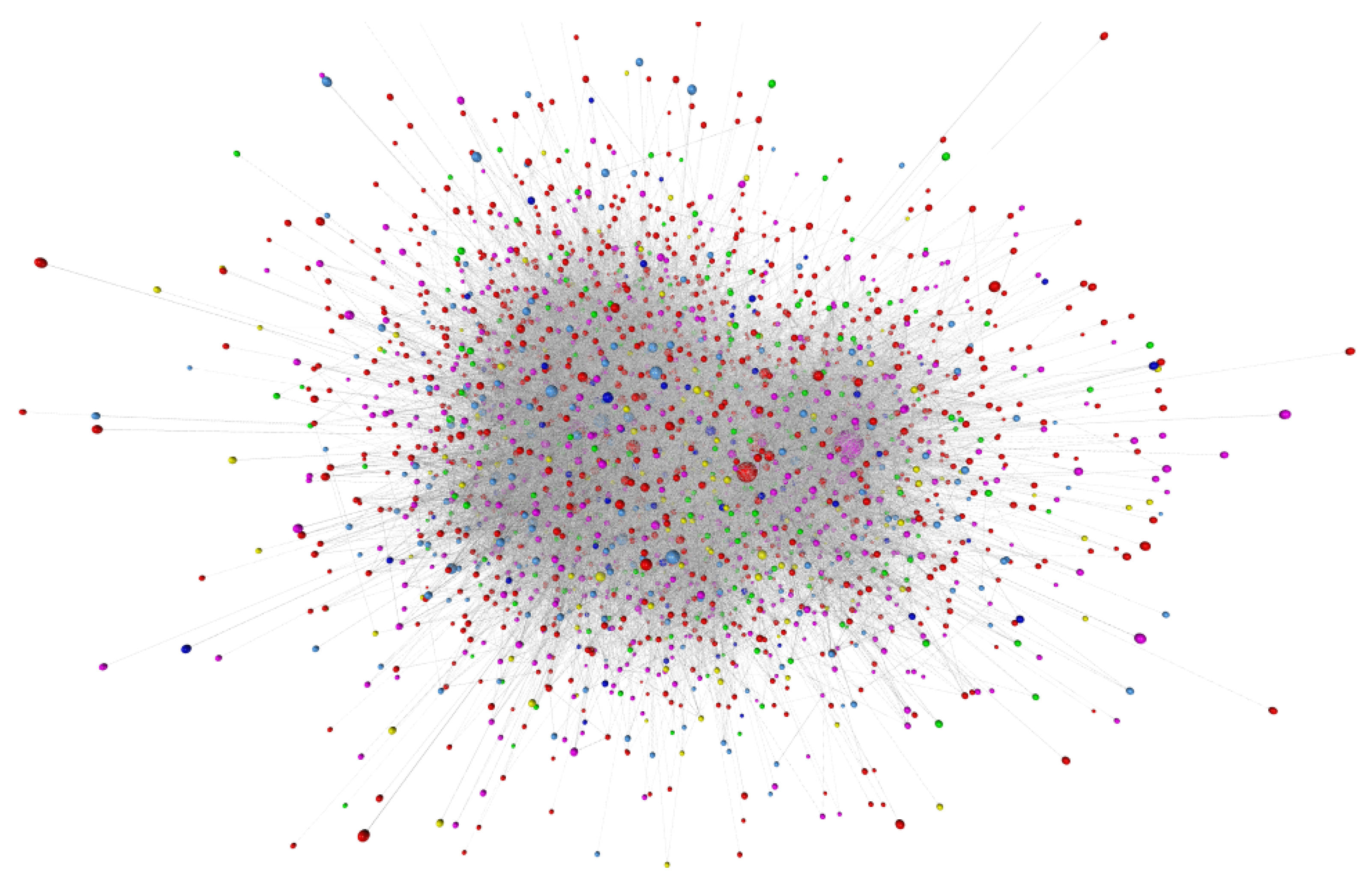

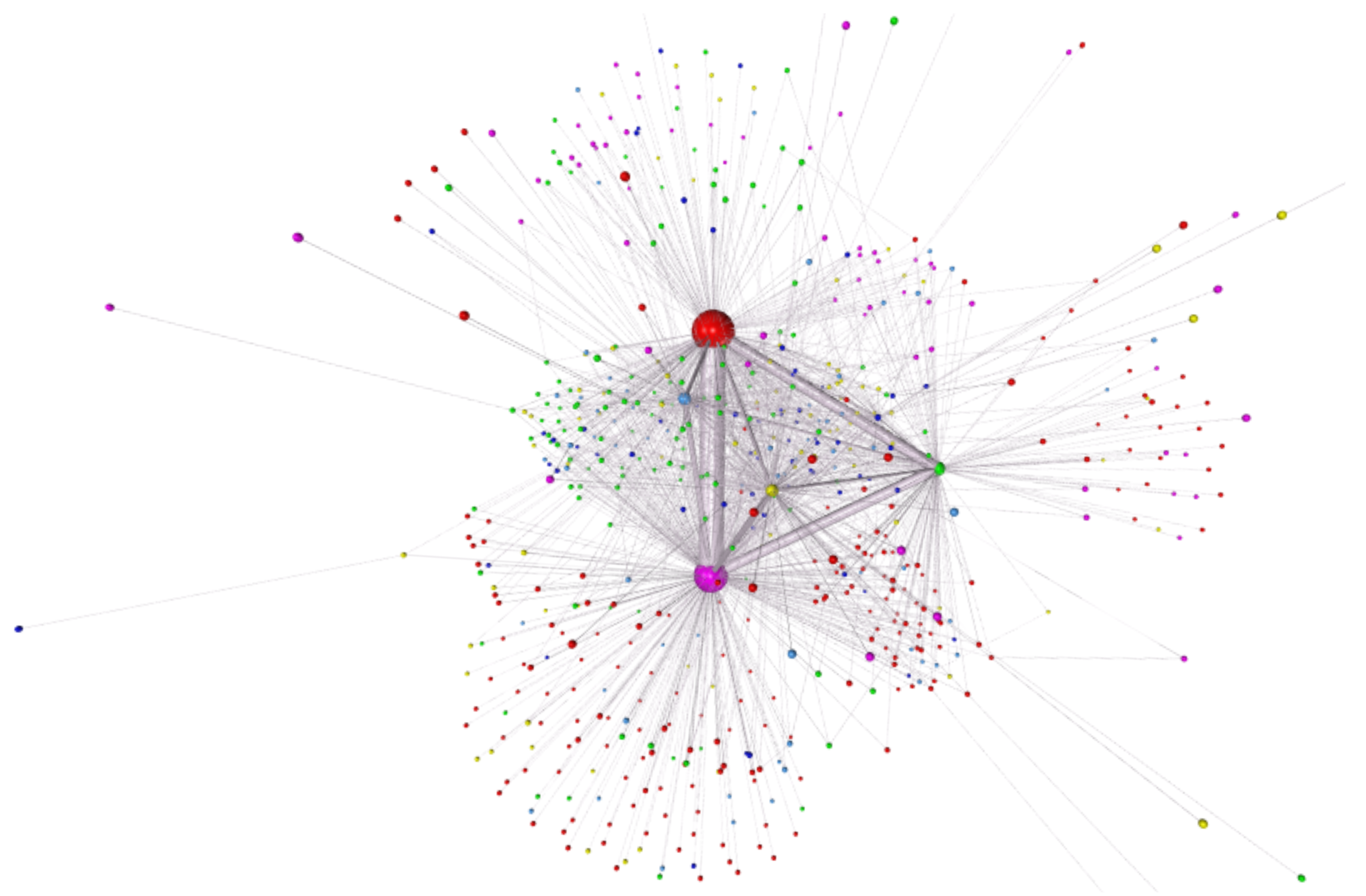

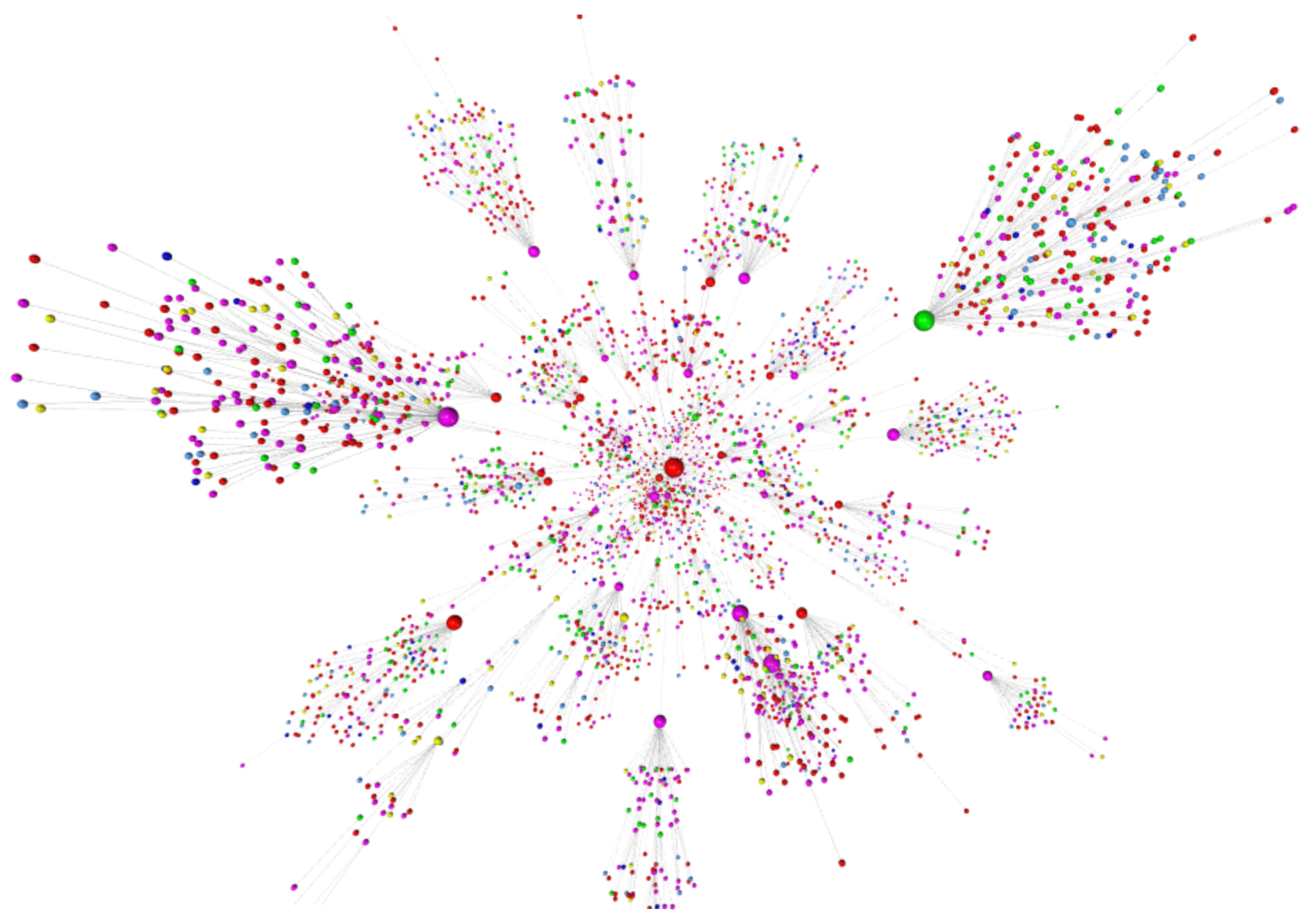

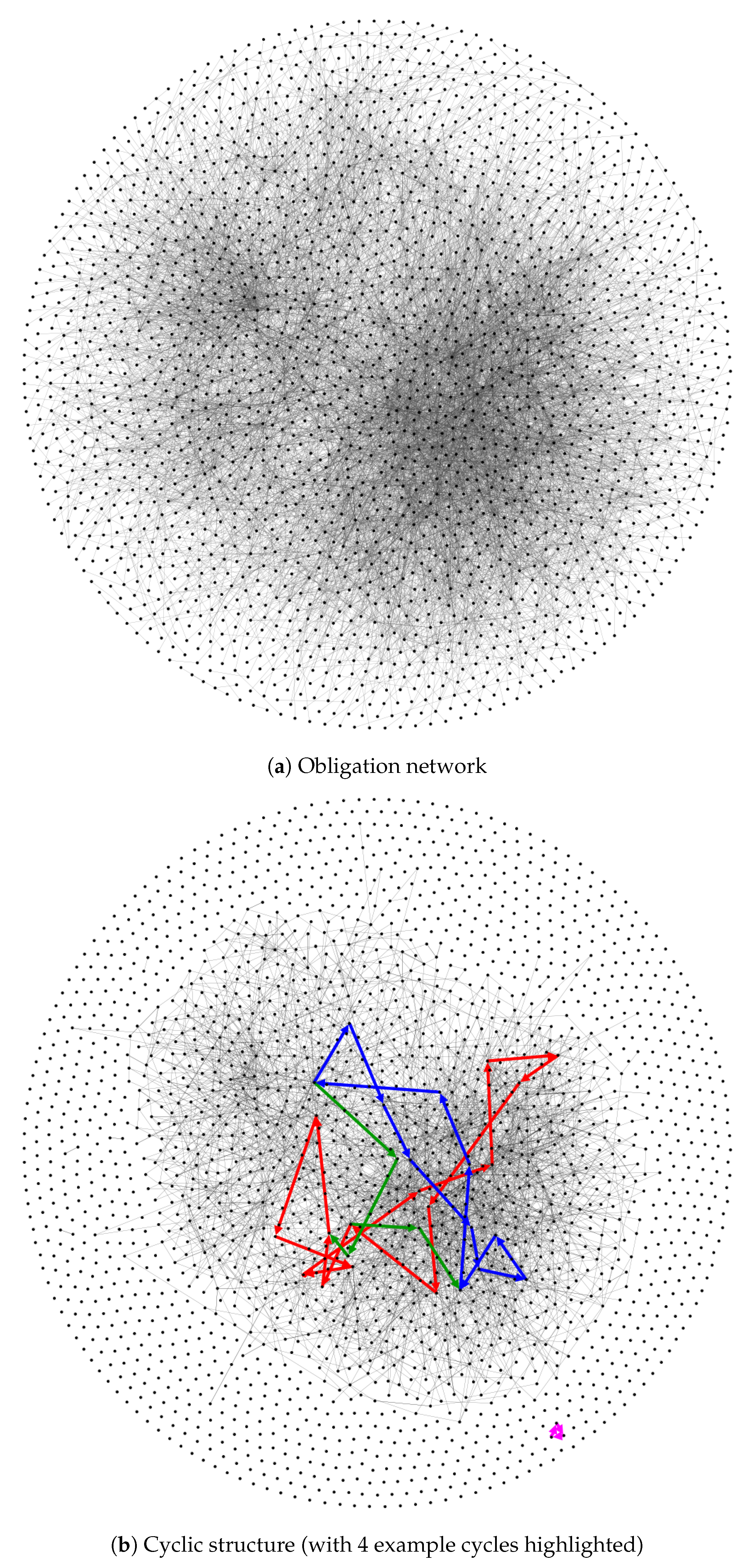

2.1.1. Network Visualization

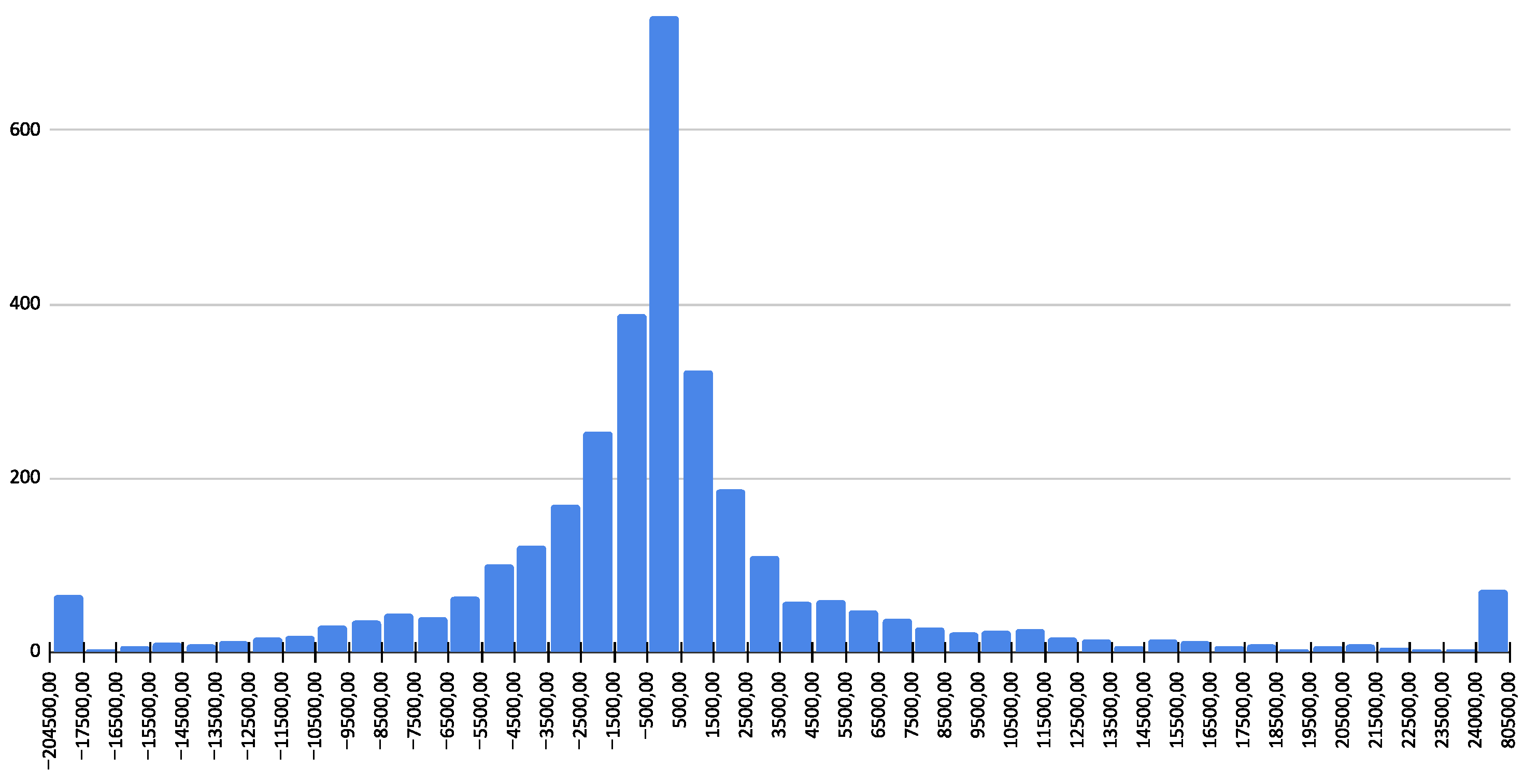

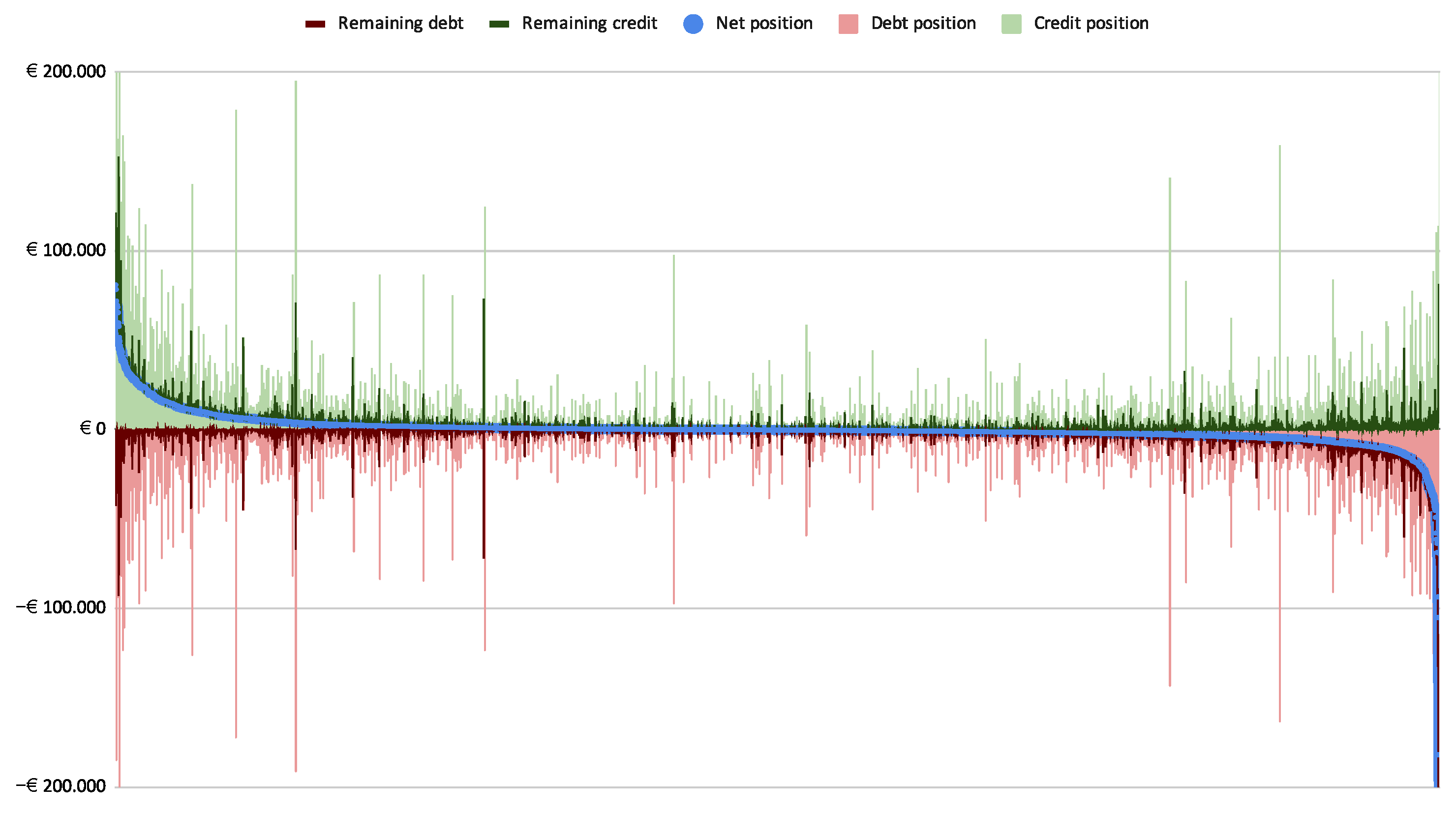

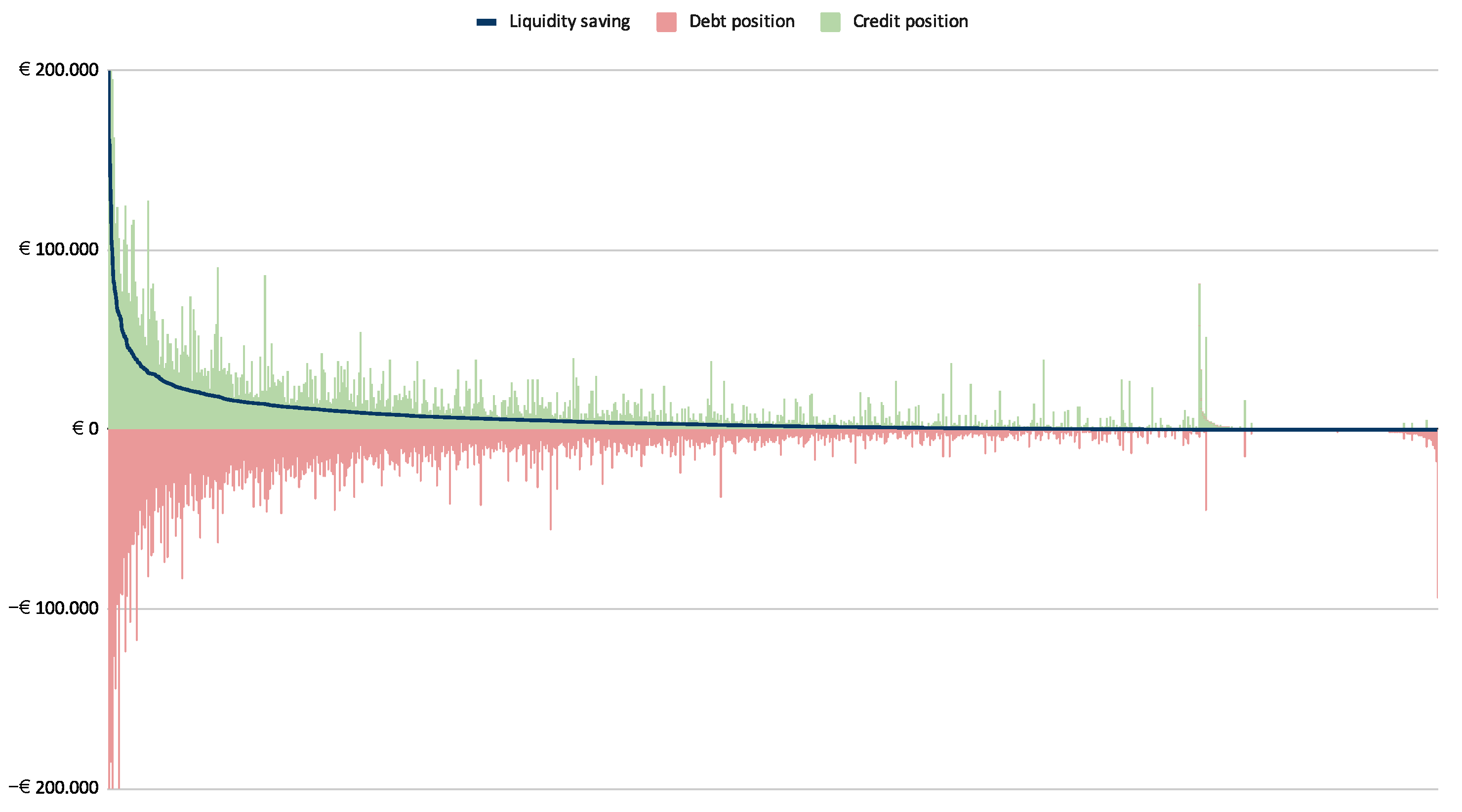

2.1.2. Stocks and Flows Visualization

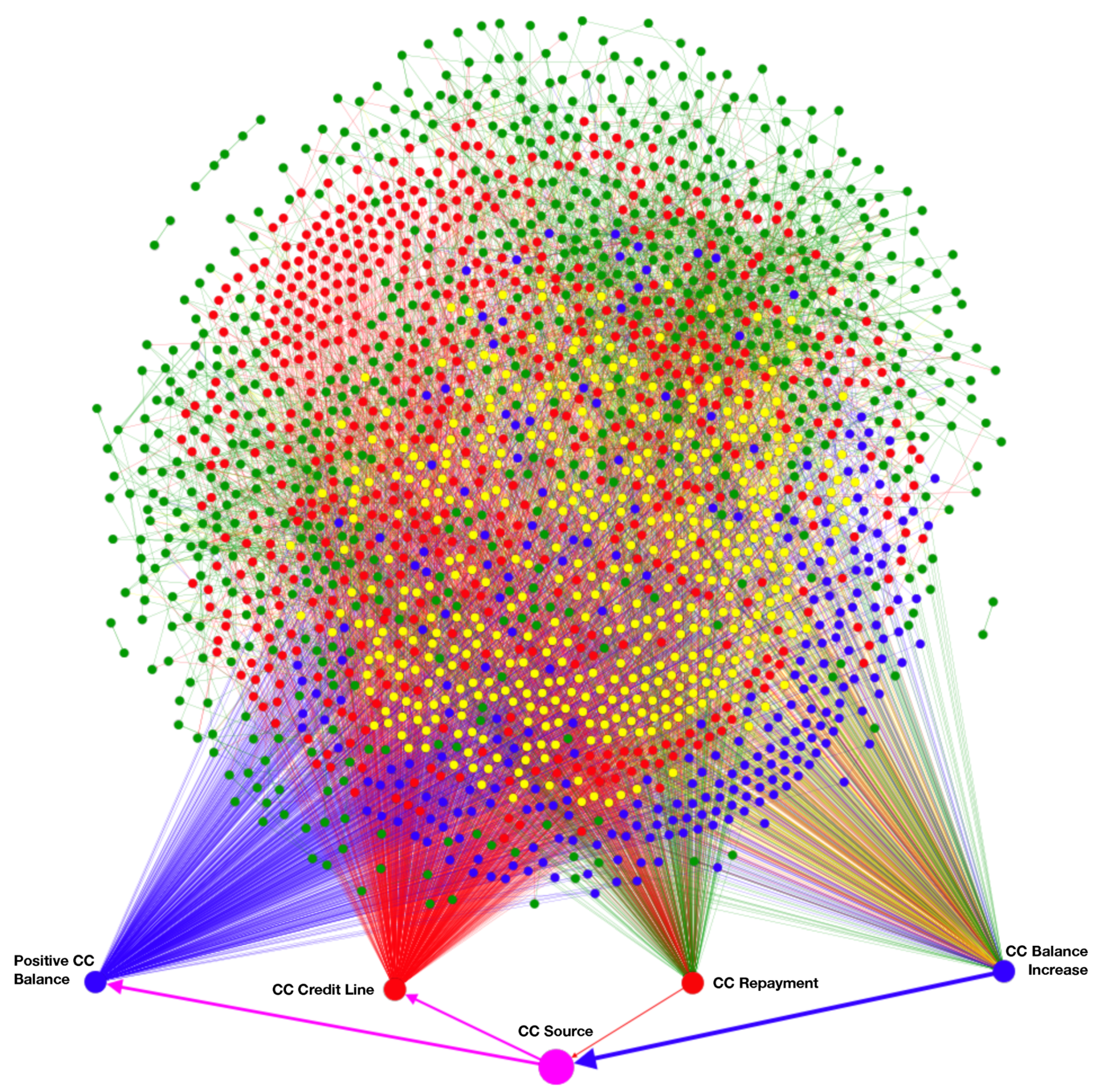

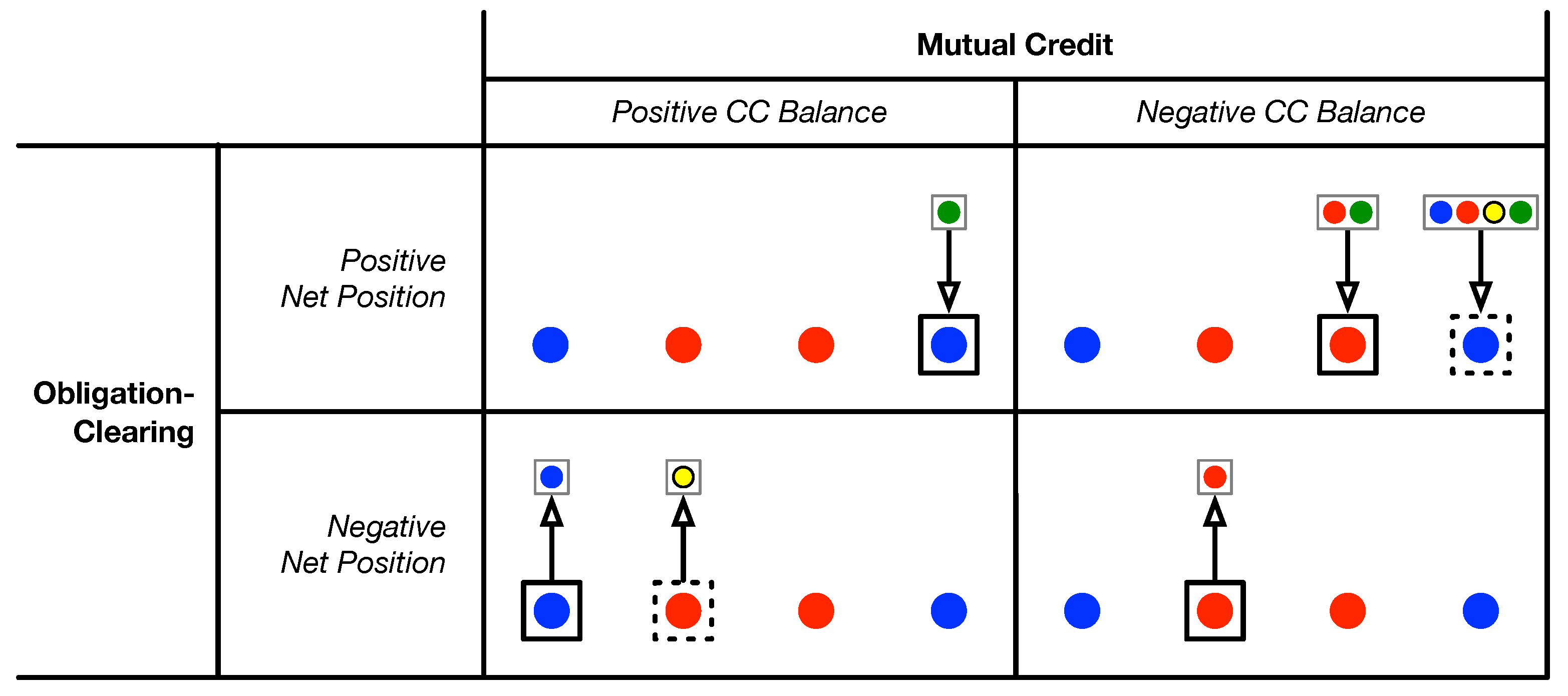

2.2. Inclusion of Simulated Mutual Credit Data in the Invoice-Netting Network

- The Euro payments that were not cleared in April have all been paid (using normal bank transfers).

- There is a distribution of positive and negative (simulated) CC balances throughout the circuit.

- Some firms have maxed out on their credit lines (i.e., their balances are negative and cannot go more negative) but the credit lines of many others are either unused or underused.

- all the Euro obligations (invoices) are entered

- all the liquidity source obligations (CC balances) are recorded and entered as well

- the resulting very complex network is analysed and a cyclic structure (much larger than when no liquidity is used) is identified

- all the obligations in the cyclic structure are cleared in a single step (the cyclic structure is “removed”)

- any remaining Euro balances are paid by normal bank transfers.

- Firms with a negative net position and positive CC balance get a link FROM the Positive CC Balance node (blue dot, bottom-left).—If their positive CC balance is smaller than their negative net position they may get an additional linkFROM the CC Credit Line node (red dot, second from the left).

- Firms with a negative net position and negative CC balance get a link FROM the CC Credit Line node (red dot, second from the left).

- Firms with a positive net position and negative CC balance are linked TO the CC Repayment node (red dot, third from the left).—If their positive net position is greater than the negative CC balance they may get an additional linkTO the CC Balance Increase node (blue dot, bottom-right).

- Firms with a positive net position and a positive CC balance are linked TO the CC Balance Increase node (blue dot bottom right).

- The overall liquidity source node (CC Source), the bigger pink dot on the bottom, is connected to the four flow-type nodes in a way that closes all the cycles. Arrow thickness is proportional to volume.

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Brief Technical Description of Tetris Core Technologies (TCT)

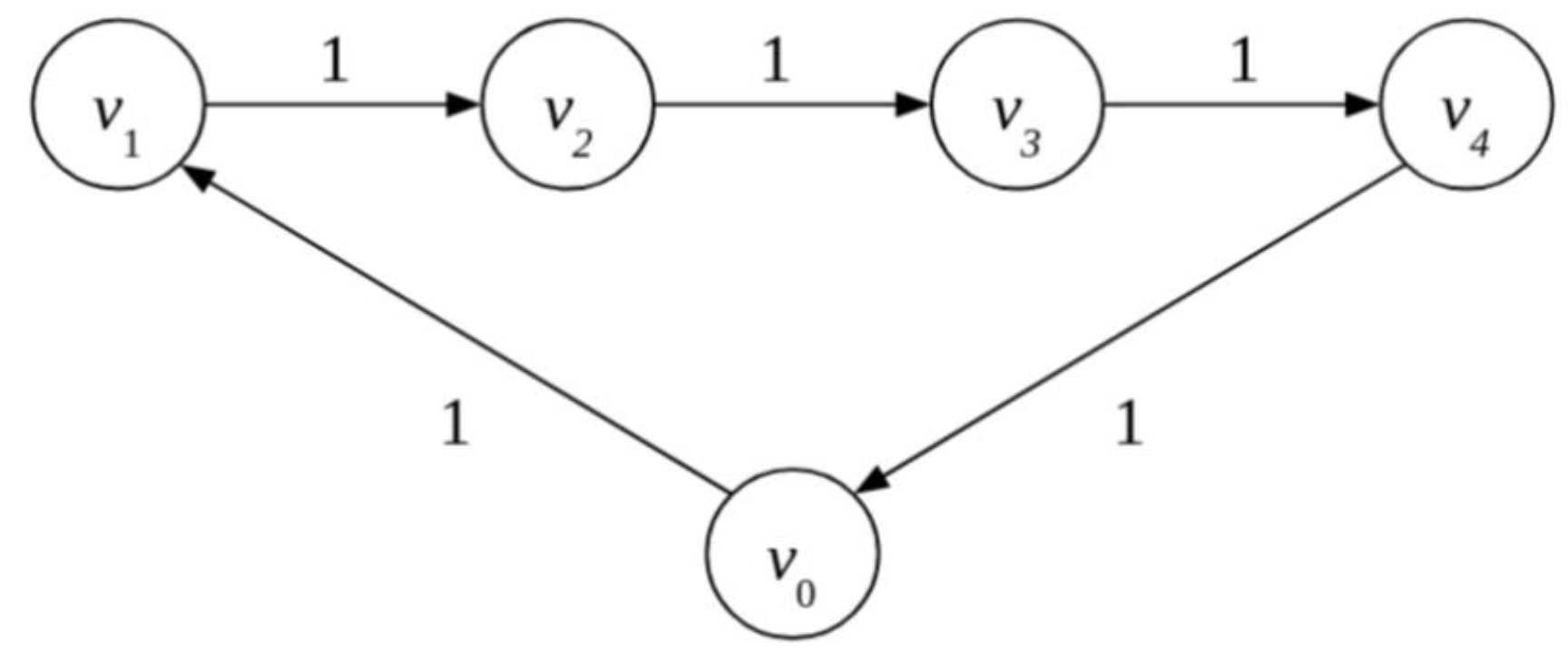

- Circular is a situation where individual payments can only be settled in a specific order. This situation is resolvable by reordering the payment queue.

- Gridlock is a situation in which several payments cannot be settled individually but can be settled simultaneously. This situation is resolvable with multilateral off-set.

- Deadlock is a situation where the individual payments can be made only by adding liquidity to at least one of the system participants.

4.1.1. Notation and Definitions

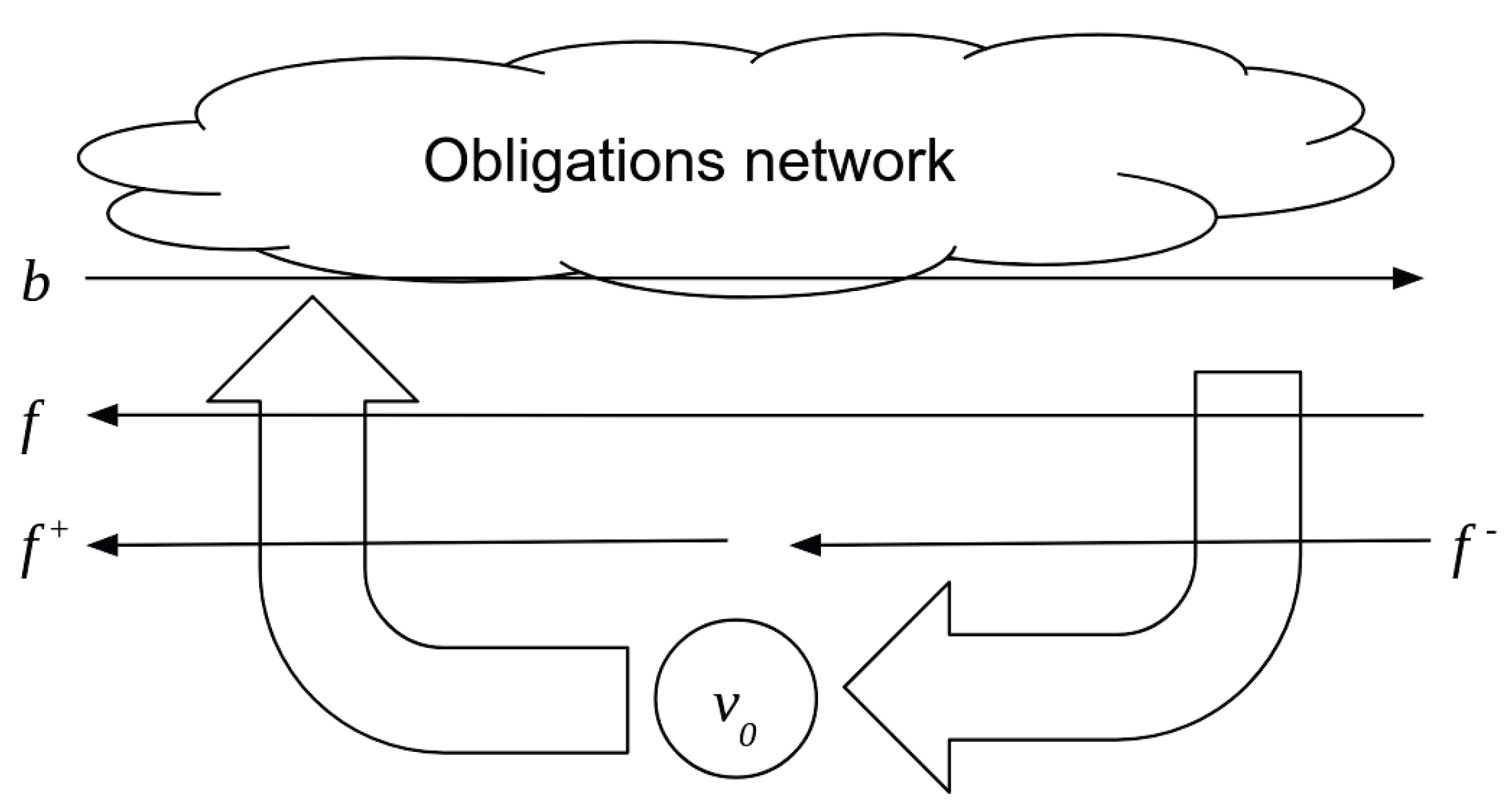

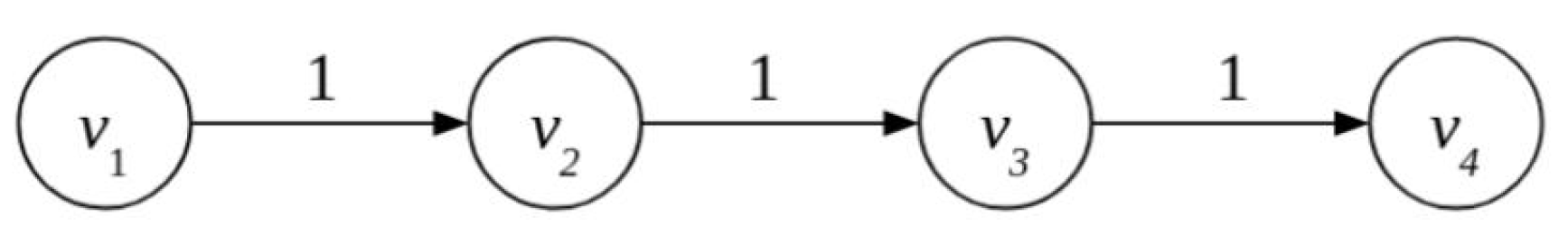

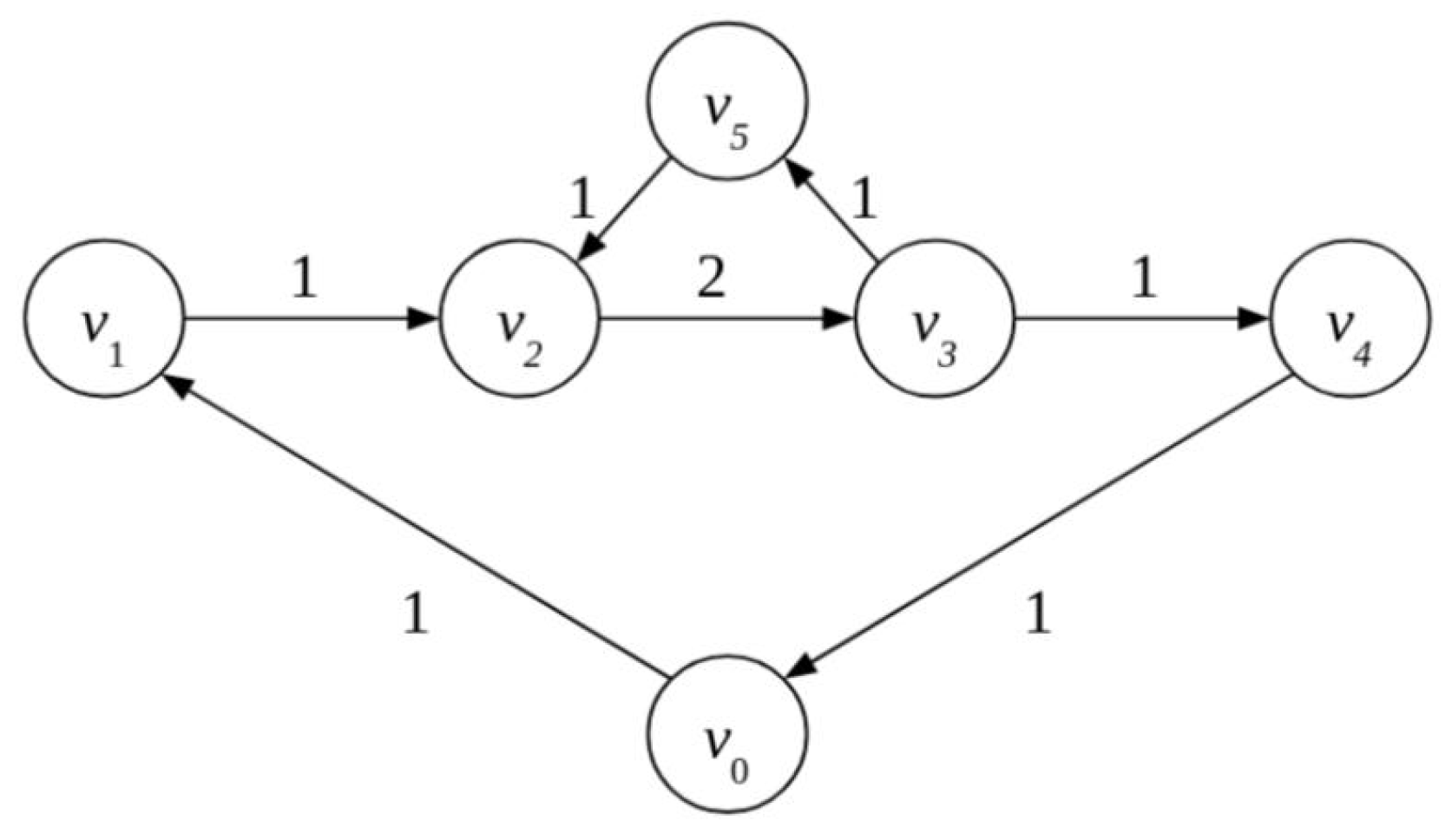

- Obligation network is a directed graph where the nodes (or vertices) represent firms and the edges represent the obligations. Parallel edges are allowed to represent multiple obligations between two firms.

- Nominal liability matrix is a matrix representing total obligations or liabilities between firms. We will define special vectors to describe the properties of the nominal liability matrix.

- Payment system is constructed by adding special function nodes to the obligation network. These special nodes represent sources of funds and a store of value. They can have connections to all nodes in the obligation network, and the set of all connections for each special node will be described by a vector.

4.1.2. Clearing All the Obligations in the Network

4.1.3. Gridlock Resolution in the Obligation Network

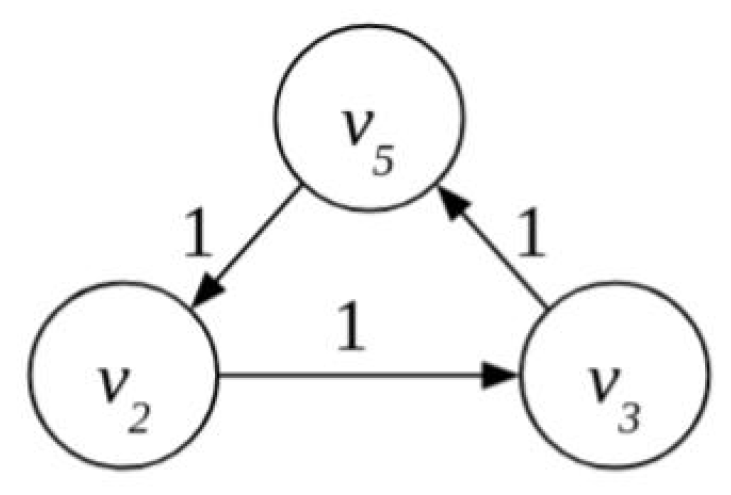

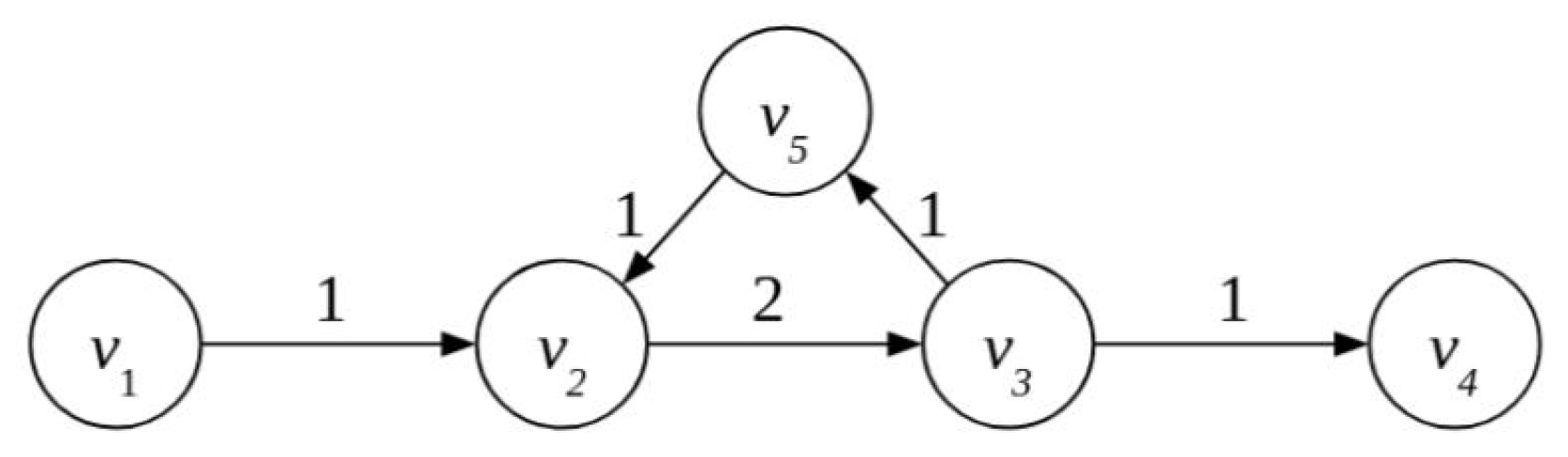

- Firm 2 borrows from an external source. That implies the need for another edge from node to node 2 with value 1. The borrowed funds can be returned to as soon as the payment from Firm 5 to Firm 2 is executed.

- Any other firm in the cycle borrows from an external source, which would require new edges from node .

- Still assuming that 1 unit arrives at from , Firms 2 and 3 agree on the partial discharge of the obligation. In this case, the partial payment of 1 unit of account from Firm 2 enables Firm 3 to discharge one of its obligations. If they decide to discharge the obligation to Firm 5, the cycle will be discharged in full. This removes the gridlock situation created by the cycle. The flow of 1 unit from through the obligation network is therefore unobstructed and all the remaining obligations can be cleared. If Firm 3 decides to discharge the obligation towards Firm 4 before Firm 5 we are back to gridlock.

4.1.4. TCT Non-Monetary Intervention

4.2. Sardex Mutual Credit

- Local: the currency is valid and can be spent only in Sardinia because only Sardinian companies are admitted into the circuit.

- Non-convertible: Sardex credits cannot be exchanged for Sterling or any other currency. They cannot be bought or sold. They can only be issued and earned by Sardinian companies (usually but not exclusively SMEs) trading in Sardinia.

- Zero-interest: all Sardex balances, positive or negative, do not accrue interest.

- Sardex is a B2B system whose membership is primarily composed of SMEs, although their employees can also participate if they voluntarily accept to receive part of their salary in credits (B2E program). More recently, Sardex has developed also a B2C product that comes with the same platform.

- The power to issue credits is distributed to all the (company) members. Credits are issued when a member goes into debt by paying for a product or service provided by another member.

- By double-entry book-keeping, for every draw-down of a buyer’s balance, which can go negative, there is an equal and opposite (i.e., positive) movement in the seller’s balance. Therefore, the sum of all the balances in the circuit is always and necessarily zero.

- Credits can also be destroyed. When a member with a positive balance pays a member with a negative balance, the credits being paid are destroyed (monetary mass decreases).

- Credit lines are on average at 2% of a member’s turnover, and they are set by the Circuit Manager.

- Circuit members commit to accepting about 10% of their turnover in credits—by selling their products and services to other circuit members.

- If the tax authority asks the Circuit Manager to provide information on the trading history of a given member, the Circuit Manager is obliged to provide it. Therefore, Sardex guarantees tax transparency even though it does not engage in or guarantee tax compliance. Tax compliance is the responsibility of each circuit member severally.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AJPES. 2002–2019 Poročila o Rezultatih VečStranskega Pobota. Agency of the Republic of Slovenia for Public Legal Records and Related Services. Available online: https://www.ajpes.si/Bonitetne_storitve/Vecstranski_pobot/Porocila#b671 (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Bardoscia, Marco, Stefano Battiston, Fabio Caccioli, and Guido Caldarelli. 2017. Pathways towards instability in financial networks. Nature Communications 8: 14416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastian, Mathieu, Sebastien Heymann, and Mathieu Jacomy. 2009. Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks. In Third International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. pp. 361–62. Available online: https://vbn.aau.dk/ws/files/328840013/154_3225_1_PB.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- BIS. 2008. The Interdependencies of Payment and Settlement Systems. Technical Report. Bank for International Settlements. Available online: https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d84.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Brandes, Ulrik. 2001. A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology 25: 163–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byck, Shaun, and Ronald Heijmans. 2020. How much liquidity would a liquidity-saving mechanism save if a liquidity-saving mechanism could save liquidity? A simulation approach for Canada’s large-value payment system. De Nederlandsche Bank Working Paper No. 682. Available online: https://www.dnb.nl/en/binaries/Working%20paper%20No.%20682_tcm47-388290.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Cuñat, Vicente, and Emilia García-Appendini. 2012. Trade credit and its role in entrepreneurial finance. In Oxford Handbook of Entrepreneurial Finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 526–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, Paolo, and Alexandros Kioupkiolis. 2019. The alter-politics of complementary currencies: The case of Sardex. Cogent Social Sciences 5: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DZRS. 1993. Official Gazette of the National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia. Available online: http://www.sistory.si/cdn/publikacije/36001-37000/36927/Porocevalec_1993-06-10_15.pdf#page=28 (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- DZRS. 1994. Official Gazette of the National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia. Available online: http://www.sistory.si/cdn/publikacije/36001-37000/36976/Porocevalec_1994-05-10_18.pdf#page=36 (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- DZRS. 1995. Official Gazette of the National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia. Available online: http://www.sistory.si/cdn/publikacije/37001-38000/37033/Porocevalec_1995-05-05_16.pdf#page=25 (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- Eisenberg, Larry, and Thomas H. Noe. 2001. Systemic Risk in Financial Systems. Management Science 47: 236–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. 2019. Exports of Goods and Services in % of GDP. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tet00003/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Fleischman, Tomazž, and Paolo Dini. 2020. Balancing the payment system. arXiv, arXiv:2011.03517. [Google Scholar]

- Flögel, Franz, and Stefan Gärtner. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Relationship Banking in Germany: Will Regional Banks Cushion an Economic Decline or is A Banking Crisis Looming? Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 111: 416–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foote, Elizabeth. 2014. Information asymmetries and spillover risk in settlement systems. Journal of Banking & Finance 42: 179–90. [Google Scholar]

- Galbiati, Marco, and Kimmo Soramäki. 2010. Liquidity-Saving Mechanisms and Bank Behaviour. Working Paper No. 400. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1650632 (accessed on 20 May 2020). [CrossRef]

- Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: The First 5000 Years. Brooklyn: Melville Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, Geoffrey. 2004. The Nature of Money. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Jonung, Lars. 2018. Demand for Money: An Analysis of the Long-Run Behavior of the Velocity of Circulation. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Juergensen, Jill, José Guimón, and Rajneesh Narula. 2020. European SMEs amidst the COVID-19 crisis: Assessing impact and policy responses. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics 47: 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, Georg Friedrich. 1973. The State Theory of Money. New York: Augustus M Kelley. First published 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen, Harry. 2005. Liquidity, risk and speed in payment and settlement systems–A simulation approach. Technical Report, Bank of Finland. Available online: https://helda.helsinki.fi/bof/bitstream/handle/123456789/9355/118263.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Littera, Giuseppe, Laura Sartori, Paolo Dini, and Panayotis Antoniadis. 2017. From an Idea to a Scalable Working Model: Merging Economic Benefits with Social Value in Sardex. International Journal of Community Currency Research 21: 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, Wallis, Paolo Dini, and Laura Sartori. 2017. Self-Funded Social Impact Investment: An Interdisciplinary Analysis of the Sardex Mutual Credit System. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 8: 149–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrak, Mojmir. 2004. Slovenia: From Yugoslavia to the European Union. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, Karl. 2001. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston: Beacon Press. First published 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, Laura, and Paolo Dini. 2016. Sardex, from complementary currency to institution. A micro-macro case study. Stato e Mercato 107: 273–304. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, Richard, Giuseppe Littera, Nigel Culkin, Paolo Dini, Luca Fantacci, and Massimo Amato. 2020. Helicopter, bazooka or drone? Economic policy for the coronavirus crisis. Politico Blog. March. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/helicopter-bazooka-drone-economic-policy-coronavirus-crisis-money/ (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Studer, Tobias. 1998. WIR and the Swiss National Economy. Basel: WIR Bank. [Google Scholar]

- SURS. 2020. GDP and National Accounts. Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. Available online: https://www.stat.si/statweb (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Tompkins, Michael, and Ariel Olivares. 2016. Clearing and settlement systems from around the world: A qualitative analysis. Technical report, Bank of Canada. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/173367/1/sdp2016-14.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Traag, Vincent A., Ludo Waltman, and Nees Jan van Eck. 2019. From Louvain to Leiden: Guaranteeing well-connected communities. Scientific Reports 9: 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dalen, Hendrik P., and Kène Henkens. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons for Financially Fragile and Aging Societies. Work, Aging and Retirement 6: 229–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | ‘Obligation-clearing’ is the most general term, ‘invoice-netting’ is the same concept applied to invoices specifically. |

| 2. | https://www.wir.ch/, since 2004 WIR Bank. |

| 3. | Local Exchange and Trading System: https://www.openmoney.org/, https://www.letslinkuk.net/. |

| 4. | The overall transaction volume for the Sardex system in 2019 was 52 million, the difference being made up of the Business to Employee (B2E) volume (11 million), trade with other Sardex-affiliated circuits in other parts of Italy (0.3 million), real-estate or capital equipment transactions (1.3 million), Business-to-Consumer (B2C) volume (6.5 million), and the trade volume of the circuit manager as a circuit member (1.4 million). We are using the GDP method to calculate the volume, not the clearing-house method. In the clearing-house method since the circuit manager acts as a central counterparty each transaction is counted twice, resulting in volume figures twice the size reported here. |

| 5. | ‘Strongly connected graph’ means that there is a route between any two nodes. ‘Complete graph’ means that there is an edge between any two nodes. |

| 6. | |

| 7. | There is more than one cyclic structure that corresponds to the single maximum set-off amount, the solution is not unique. |

| 8. | Liquidity-saving can also refer to the amount of debt saved (“debt-saving”). |

| 9. | We remind the reader that the original data does consist of Sardex credits, but we are treating it as if it were all Euros, and are then adding a fictitious CC system on top, as explained in the text. |

| 10. | The “Euro” turnover was calculated by adding up all the transactions for each firm for the 2019 data set being used. |

| 11. | Created with the Gephi (Bastian et al. 2009) network visualization tool. |

| 12. | The presence of the liquidity-based cycles indirectly affects also the part of the cyclic structure that does not rely on liquidity. |

| 13. | In the empirical sciences this is generally known as dimensional analysis and is the basis of the search for dimensionless combinations of variables that “collapse” clouds of data points into surjective relationships that can be curve-fitted to a single function. The method was developed roughly in the same period, in the 19th century, as group theory in abstract algebra, of which it eventually became clear that it was an application, along with many areas of physics. |

| 14. | |

| 15. | Following a referee suggestion we are including a minimal description of TCT’s mathematical underpinnings. Please see (Fleischman and Dini 2020) for a more complete presentation of the general theorems. |

| 16. | AJPES stands for “Agency of the Republic of Slovenia for Public Legal Records and Related Services”. They are responsible for: registry keeping, collection, processing and publication of annual reports, statistical research and data collection, credit rating operations, and other commercial activities. https://www.ajpes.si/. |

| TCT Input | TCT Output | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

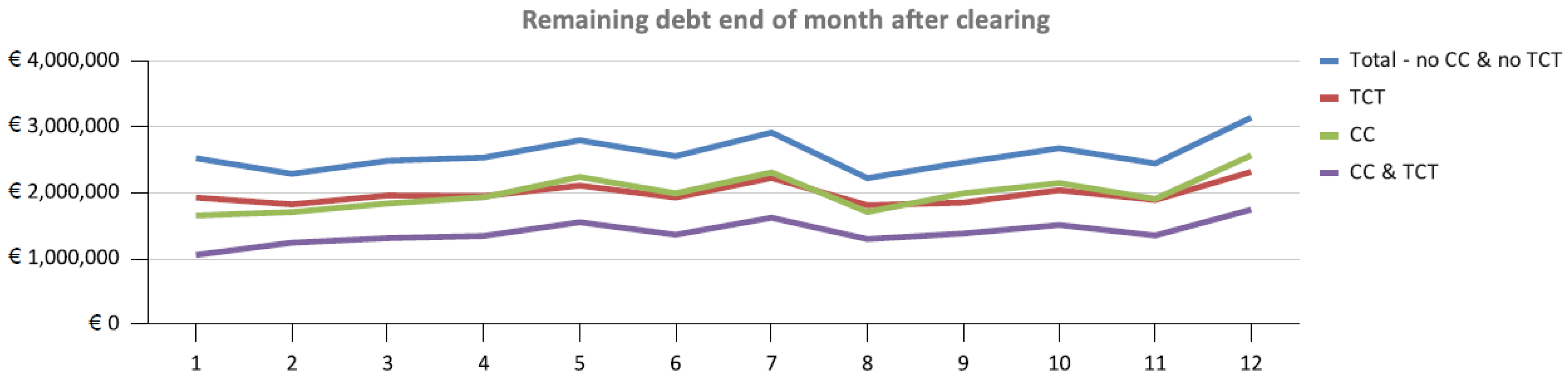

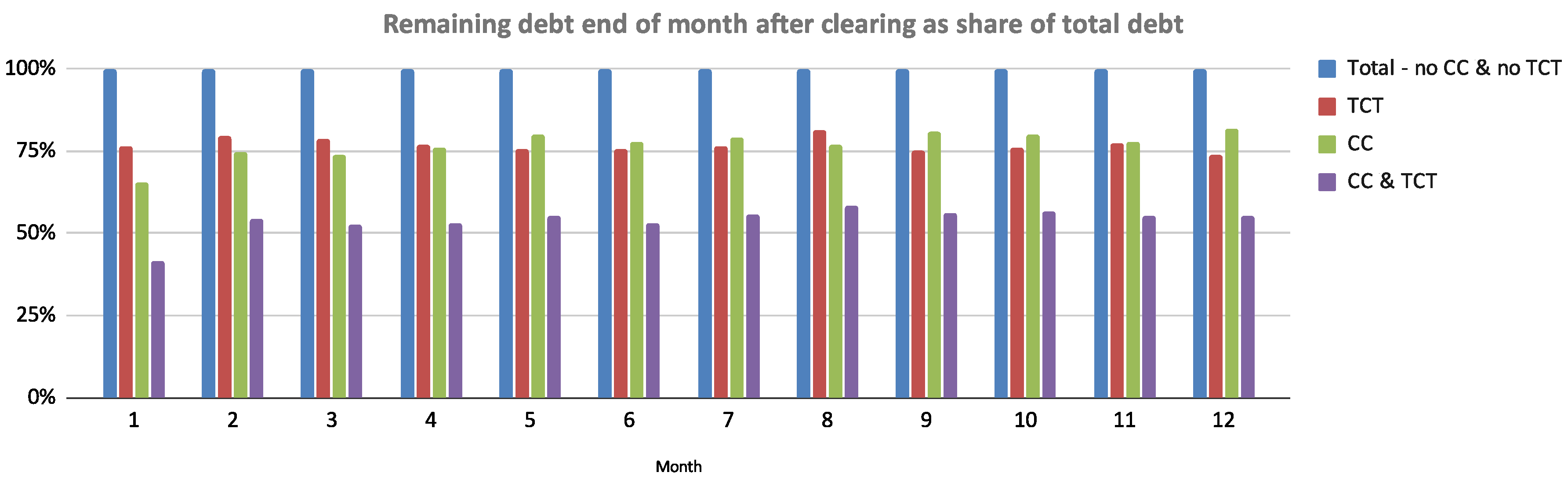

| Total | # | Cycles | # | Remaining | ||||

| Month | EUR | Invoices | EUR | % | Invoices | % | EUR | % |

| 1 | 2519 | 10,824 | 597 | 23.7% | 4638 | 42.8% | 1921 | 76.3% |

| 2 | 2284 | 10,192 | 464 | 20.4% | 3951 | 38.8% | 1819 | 79.6% |

| 3 | 2481 | 11,603 | 526 | 21.2% | 4396 | 37.9% | 1955 | 78.8% |

| 4 | 2531 | 11,359 | 586 | 23.2% | 4115 | 36.2% | 1944 | 76.8% |

| 5 | 2792 | 12,302 | 687 | 24.6% | 5590 | 45.4% | 2104 | 75.4% |

| 6 | 2551 | 11,505 | 628 | 24.6% | 4338 | 37.7% | 1923 | 75.4% |

| 7 | 2910 | 12,408 | 688 | 23.7% | 5246 | 42.3% | 2221 | 76.3% |

| 8 | 2217 | 10,183 | 411 | 18.6% | 3442 | 33.8% | 1806 | 81.4% |

| 9 | 2456 | 11,271 | 609 | 24.8% | 4471 | 39.7% | 1847 | 75.2% |

| 10 | 2671 | 12,134 | 636 | 23.8% | 5160 | 42.5% | 2035 | 76.2% |

| 11 | 2441 | 11,538 | 555 | 22.8% | 4776 | 41.4% | 1885 | 77.2% |

| 12 | 3137 | 13,007 | 823 | 26.3% | 5723 | 44.0% | 2313 | 73.7% |

| mean | 2583 | 11,527 | 601 | 23.1% | 4653 | 40.2% | 1981 | 76.9% |

| Function or Property | Fiat | Obligation-Clearing | Mutual Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit of Account | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Medium of Exchange | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Means of Final Payment (e.g., taxes) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Store of Value | Yes | No | Weak, by design |

| Avg. lifetime between creation and destruction | Years | Microseconds | Months |

| Velocity of circulation | ≈1 | ≈8 | ≈5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fleischman, T.; Dini, P.; Littera, G. Liquidity-Saving through Obligation-Clearing and Mutual Credit: An Effective Monetary Innovation for SMEs in Times of Crisis. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13120295

Fleischman T, Dini P, Littera G. Liquidity-Saving through Obligation-Clearing and Mutual Credit: An Effective Monetary Innovation for SMEs in Times of Crisis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2020; 13(12):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13120295

Chicago/Turabian StyleFleischman, Tomaž, Paolo Dini, and Giuseppe Littera. 2020. "Liquidity-Saving through Obligation-Clearing and Mutual Credit: An Effective Monetary Innovation for SMEs in Times of Crisis" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13, no. 12: 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13120295

APA StyleFleischman, T., Dini, P., & Littera, G. (2020). Liquidity-Saving through Obligation-Clearing and Mutual Credit: An Effective Monetary Innovation for SMEs in Times of Crisis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(12), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13120295