This section provides an overview on community currencies and the issue of seasonally insufficient money supply. It then draws attention to a gap which community currencies may fill and derives a working hypothesis.

2.1. Community Currencies

Community currencies are a sub-group of so-called complementary currencies – which are so termed because they function complementarily to a major currency, providing an additional money supply (

Seyfang and Longhurst 2013, p. 65). The sub-group of community currencies are distinguished by their aim to “support and build more equal, connected and sustainable societies” (

CCIA 2015, p. 43) for a specifically defined group (

Seyfang and Longhurst 2013, p. 65). One possibility to define such a group is using geographic boundaries, which we focus on. While community currencies may also address ecological or social aims, we solely focus on the economic impact which community currencies have.

Essentially the same as any other currency, a community currency is used as a means of payment. It may hold the traditional functions of money: means of exchange, store of value and unit of account (

Collins et al. 2012, p. 39). The function of store of value is debated in literature (e.g.,

Zagata 2004, p. 481;

Slay 2011, p. 3;

Martignoni 2012, p. 5;

CCIA 2015, p. 100), which we address in

Section 2.2. Some community currencies require collateral, that is, national currency needs to be exchanged to obtain the community currency. Others work as a mutual credit system, using peer pressure as a form of social collateral and enabling access to anyone within the network. As such, it is created between members as a transferable loan without interest (

Bonanno 2018, p. 91). Restricted to a geographical area, a community currency covers only a specific group which accepts the currency as an additional means of payment. As a community currency is usually not convertible into another currency (including the official national one), it cannot leave the region of validity and as such cannot become scarce. Thus, it may complement other currencies with constant additional liquidity (

Schraven 2001, p. 9) or an additional form of money supply, providing an alternative when the supply of official currency is not sufficient.

The origins to this movement criticizing money lie in the 1920s. Motivated by Silvio Gesell’s theory of freigeld, which translates freely into “free money”, a movement criticizing money grew stronger in the 1920s. In their focus was the inherent property of money to keep its value stable while physical investments do not (

Godschalk 2011, p. 4). The movement especially criticized the overly slow circulation of money and aimed to speed it up using a new kind of currency. It had the inherent feature to continually lose its value, which was termed demurrage. Most prominently, the Austrian town of Wörgl introduced a community currency in 1932, during an economic recession. Unemployment rates decreased due to an increase in commercial interactions within the community network; investments and employment were paid for with community currency and could, in consequence, be increased. Demurrage forced the money to circulate more quickly, which led to a social product nine times as efficient as conventional money. However, the central bank stopped the experiment six months after it had started (

Lukschandl 2020).

The idea fell dormant after the initial experiments in the 1930s but found a revival in the 1990s. Since then, numerous community currencies have been introduced in the Global South and the Global North which vary greatly in their respective implementations. As of 2012, over 5000 complementary currencies had been established (

Martignoni 2012), with 3418 complementary currencies still active in that year (

Seyfang and Longhurst 2012, p. 11). Academic evaluation has increased in the past decades, allowing for a closer study of economic and social impacts. In academia, the impact of community currencies is debated, especially on an economic level.

Despite the fact that community currencies are sometimes economically motivated, not many studies show economic advantages. Only half of the community currencies have any economic impact, while only a third enables access to goods and services which would otherwise be unaffordable. Only a quarter of community currencies increase members’ income (

Michel and Hudon 2015, p. 165). In the Global South, Bangla-Pesa and Red de Trueque are prominent examples of community currencies with clear economic benefits. Within the Bangla-Pesa community, 83% of members reported an increase of sales, with transactions in the community currency accounting for 22% of average daily sales (

Ruddick et al. 2015, pp. 27–28). The Red de Trueque in Argentina gained momentum during an economic crisis 1999–2002 (

Gomez and Helmsing 2008, p. 2495). At its peak, up to 25% of participant households’ income was earned in the community currency. It even provided something close to a minimum wage employment (

Slay 2011, pp. 13–14). On the other hand, community currencies in the Global North such as the Bristol Pound and Ithaca Hours lack evidence of economic benefits. The Bristol Pound does not facilitate local procurement, nor does it add to local production (

Marshall and O’Neill 2018, p. 277). A survey found that for two-thirds of Ithaca Hours members, the community currency does not enable access to goods or services they otherwise would not be able to access (

Slay 2011, p. 13). Additionally,

Krohn and Snyder (

2008, p. 65) did not find quantitative evidence of community currency-related growth. How can the discrepancy between community currencies with and without economic benefits be explained?

One argument is that community currencies appear to provide economic advantages when addressing a failure within the existing monetary system (

Slay 2011, p. 13). We follow this line of thought and introduce the issue of seasonal shortages in money supply as a failure within the existing system in the next section. We then elaborate on how community currencies may help address this issue.

2.2. Seasonal Shortages in Money Supply

In a modern society, the money supply in circulation serves three functions: unit of account, means of exchange, and store of value (

Collins et al. 2012, p. 39). While the unit of account is an abstract measure to compare different goods and services, the latter two functions are economically more directly meaningful. As a means of exchange, money ensures individuals meet their demands of goods and services. Instead of offering goods or services in direct return, they use money as a fungible intermediary. As a store of value, money keeps a stable value over the course of time (

Godschalk 2011, p. 4). These two functions of money are mutually exclusive; if money is exchanged for a good or service, it cannot be saved at the same time.

To profit from the means of exchange function of money, individuals and societies as a whole need to ensure a sufficient money supply to enable all possible transactions, or a sufficient level of liquidity. This can be understood within the framework of the equation of exchange,

where

M refers to the money supply,

V to the velocity with which the money circulates,

P to the prices of goods and services which are traded, and

T to the number of transactions taking place (

Fisher 1912, p. 26). Both sides of the equation describe an economy’s gross domestic product (GDP). We understand the right side of the equation as a given constant determined by the equilibrium of demand and supply. Although we acknowledge the impact of changes in the velocity V to be important (as emphasized by

Stodder 2009;

De la Rosa and Stodder 2015;

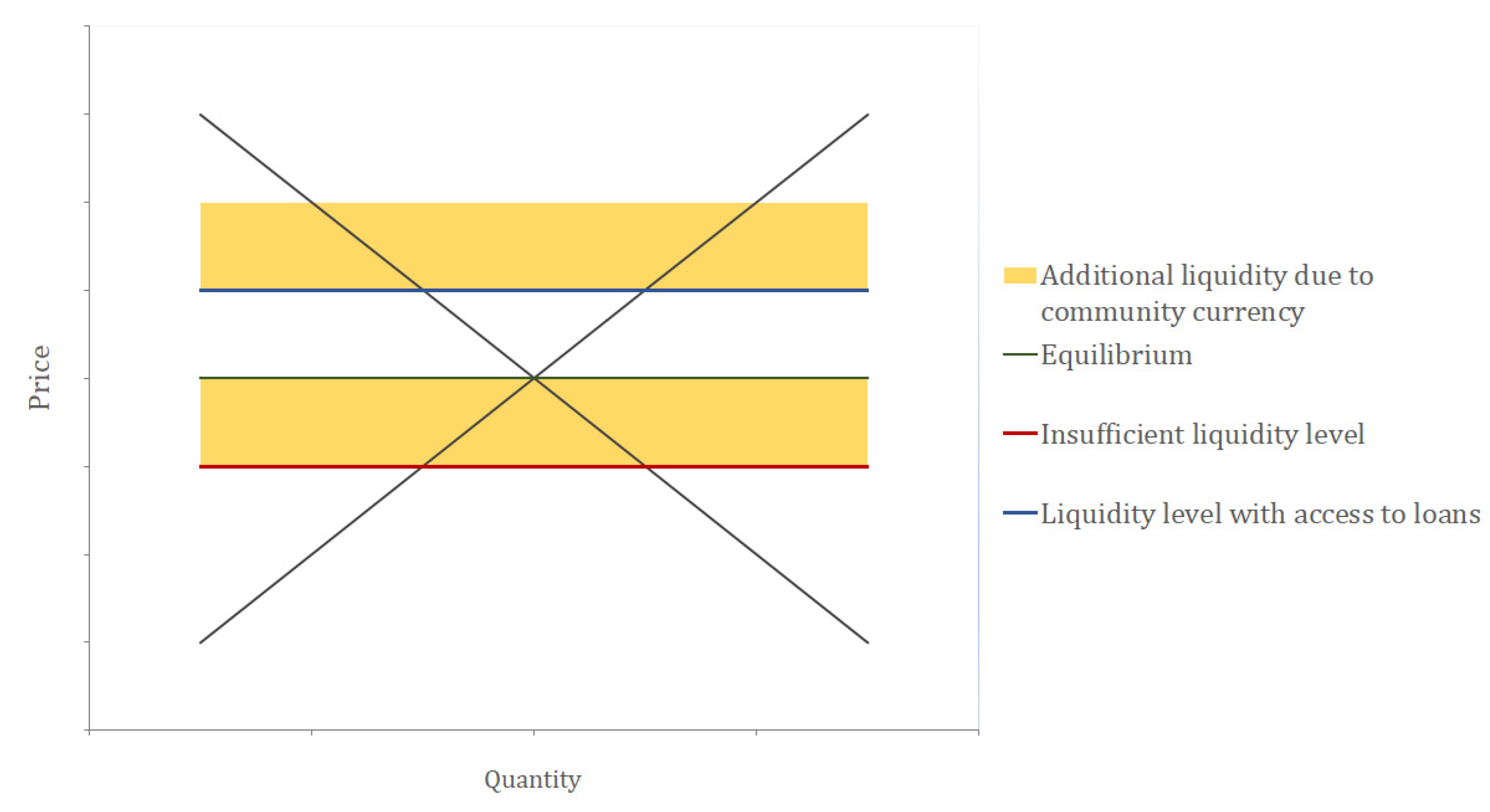

Stodder and Lietaer 2016), we assume it to be constant to focus on the impact of money supply M. If the money supply M is sufficient to fulfill all desired transactions T at prices P, we speak of “sufficient liquidity”. However, if the money supply M is insufficient to fulfill an individual’s or a society’s demands, we speak of “insufficient liquidity”. In this state, money cannot completely function as a means of exchange, preventing possible transactions. Since consumers lack sufficient funds, supply does not fully meet demand. This leads to a decreased GDP, either for an entire nation or in a local economy. This imperfect allocation of goods and services leads to both excess supply on the producers’ side and excess demand from the consumers’ perspective, as can be seen in

Figure 1. Insufficient liquidity thus induces a negative welfare effect.

While constantly insufficient liquidity may lead to a new equilibrium of supply and demand, seasonal changes in money supply pose a unique problem. Supply and demand during a season of sufficient liquidity create an equilibrium; during a season of insufficient liquidity, the equilibrium cannot be reached due to a lower money supply. However, demand and supply may be relatively stable. This leads to the imperfect allocation of goods and services introduced above, seasonally reducing an economy’s welfare. Additionally, money cannot fully serve as a store of value in a situation of insufficient liquidity. The money supply is already insufficient to fully serve as a means of exchange. The two functions of money are mutually exclusive, so only money which is not used as a means of exchange can be saved. The scarce money supply thus leads to decreased savings. Hence, money cannot fully function as a store of value. In this way, seasonally insufficient money supply leads to a situation in which money can neither completely fulfill its functions as a means of exchange nor store of value.

Even though the effects of the seasonal variation in the money supply are substantial, literature on this topic are quite scattered. Seasonal variation in money supply is acknowledged in empirical studies; however, it is usually controlled for, instead of being studied in its own right (e.g.,

Roffia and Zaghini 2007). Seasonality is treated as an error in variables (

Sims 1974, p. 618), ignoring that it may have significant effects on the economy. In one of the rare studies that focus on seasonal patterns, the authors find that seasonal fluctuations significantly impact consumption and investment (

Barsky and Miron 1989, p. 504). However, little research exists on how this seasonal fluctuation in money supply affects local and national economies.

In a situation of seasonally insufficient liquidity, we thus identify three core economic disadvantages:

Decreased sales: Imperfect allocation leads to excess supply, that is, less sales than in a situation of sufficient liquidity (means of exchange).

Decreased consumption. Imperfect allocation leads to excess demand, that is, less consumption than in a situation of sufficient liquidity (means of exchange).

Decreased savings. Consumers lack sufficient liquidity to meet their demands, so they also lack excess funds which could be saved (store of value).

Seasonal liquidity is present especially in rural areas with a majority of population employed in the agricultural sector. In these local economies, income is created once a year during harvest season (

Hong and Hanson 2016, p. 5). It constantly decreases as goods and services, such as fertilizers, are consumed (

Fink et al. 2018, p. 1). Such investments are not only local but also done in urban areas, and therefore continually decrease liquidity for the entire rural area. The poor especially are affected by seasonal income as they are forced to cut food intake with decreasing liquidity (

Lipton 1986, p. 4). This seasonality is especially pronounced with volatile food prices, as consumption additionally decreases as food prices increase (

Kaminski et al. 2014, p. 24).

Bank credits usually address these problems, offering extra funds to individuals and businesses when they lack sufficient liquidity to meet their demands. However, especially in rural areas in the Global South, many of the poor who are in need of credits do not have access to financial institutions (

Demirguc-Kunt et al. 2018, p. 35). The offers of these institutions is not tailored to the poor rural population. In this situation, individuals with seasonally low liquidity cannot increase their funds. A solution specific to rural areas in the Global South is the microfinance concept. Using the peer pressure of dense rural networks, it does not require collateral but rather depends on mutual trust in a group of individuals which share a credit. The concept allows individuals to access credits who would not be considered credit-worthy in a different context. However, the interest rates are high in comparison to ordinary bank credits, diminishing liquidity in a long-term perspective. It may therefore constitute a poverty trap for borrowers (

Ahlin and Jiang 2008, p. 14). Also, microfinance institutions draw on money supply that already exists in the region. In a season of insufficient liquidity, this means a re-distribution of already few resources, instead of additional money supply which is needed to address the issues enumerated above. Microcredits therefore appear to be a suboptimal or even a counter-productive solution for seasonally insufficient liquidity. In the following analysis, we therefore do not consider microcredit as an option to alleviate liquidity issues, but rather introduce an alternative.

2.3. Community Currencies in a Situation of Seasonally Insufficient Liquidity

In a situation with seasonally low liquidity alleviated by neither bank nor microfinance credits, a community currency may have a stabilizing effect on the money supply. In terms of the equation of exchange, it offers an additional source of money supply

M, enlarging the money supply

M to

where

MN is the supply of national currency and

MC is the supply of community currency. While M

N fluctuates throughout the year,

MC stays constant, stabilizing the overall money supply for the community. This is true for community currencies both with and without collateral. For a community currency without collateral, the introduction of the community currency increases the total money supply

M. A community currency which does draw on collateral (i.e., national currency has to be exchanged into community currency) does not change the initial total money supply

M. However, we neglect this effect and assume that the amount of issued community currency is too low in comparison with the national money supply to cause inflation. This paper solely focuses on the effect of a community currency to stabilize the money supply, in the awareness that this is only one factor in explaining its economic impact.

As a means of exchange, the community currency is not as fungible as national currency (

Stodder 2009, p. 84) since the transactions are limited to the community. Therefore, the national currency is generally preferable. However, in a situation of insufficient liquidity, a transaction with a community currency is preferable to no transaction. Thus, a dual-currency system appears, in which some transactions are fulfilled in community currency, and others in national currency. If some transactions which are prevented by insufficient liquidity of the national currency can be fulfilled with community currency, the welfare losses can be decreased (as symbolized by the yellow area in

Figure 1). In this way, economic advantage is created. This can be measured directly in increased sales and consumption.

The community currency also has an effect on money as a store of value. If only a single currency is used, this function competes directly with the function as a means of exchange. However, in a dual-currency system, different currencies can take different functions. As the community currency is less fungible, it is preferable to spend it as quickly as possible. Therefore, while a community currency can function as a store of value (

Slay 2011, p. 3;

Martignoni 2012, p. 5;

Zagata 2004, p. 481), this function is outweighed by its function as a means of exchange (

CCIA 2015, p. 100). Since the national currency is more fungible, it is more likely that members save it, using it as a store of value. This effect can be measured in increased savings of the national currency.

A community currency may thus stabilize a local economy in a situation of seasonally insufficient liquidity. In stabilizing the money supply, it may help to obtain the equilibrium between supply and demand, and thus increase both sales and consumption. It may increase savings, mainly in national currency. A community currency may therefore be a viable alternative to traditional ways of addressing seasonally insufficient liquidity and provide a tool to stabilize local economies. Hence, we assume community currencies are economically advantageous to the local community in a surrounding of insufficient liquidity.

2.4. Hypothesis

This line of thought leads us to the following set of hypotheses. Since it is difficult to directly prove a hypothesis, we wish to reject its opposite. We therefore formulate the hypothesis aligning with the theoretical framework provided above as the alternative hypothesis, H0 and H1.

H0: Community currencies are only economically advantageous in an environment of sufficient liquidity.

H1: Community currencies are only economically advantageous in an environment of insufficient liquidity.

In the following section, we test the hypothesis presented above qualitatively by regarding two cases of different community currencies: the German Chiemgauer and the Kenyan Sarafu Credit. While the Chiemgauer operates in a surrounding of sufficient liquidity, the Sarafu Credit operates in a surrounding of seasonally insufficient liquidity. We use the three indicators discussed in

Section 2.3 to measure the respective community currency’s impact: sales, consumption and savings. If these indicators increase due to the community currency, we assume the community currency is economically advantageous. If none of these indicators improve due to the community currency, we assume it does not have a positive economic impact. If these cases lead to a rejection of the null hypothesis, we assume the alternative hypothesis to be true. Community currencies are then only able to unroll their full potential of additional money supply if they operate in a surrounding of insufficient liquidity.