1. Introduction

Every financial crisis poses the question of what sustains money and how it recovers from a downfall. In the last financial crisis, these questions were coupled with reflections on whether a different understanding of money should not imply another regulatory framework to prevent or ameliorate the toll that crisis takes on human beings. A discussion on the configuration of money and its stability hence seems timely.

There are two main narratives on the origin and meanings of money, one which corresponds to a spontaneous or evolutionary approach, and the other a centrally designed or rule oriented approach.

Tymoigne and Wray (

2006, p. 1) explain that in one view money is portrayed as a “cost-reducing innovation to replace barter” while in a rather unknown way individual utility maximizers settled on a single numeraire. This narrative translates in modern days into money being considered a given because it has happened an undefined long time ago and it is sustained by the expectation that it will continue to function. In contrast, heterodox approaches to money underline its social and political essence as the outcome of a historical process of negotiations and impositions by central authorities. The process is ongoing. Money is conceptualized as an institution which links individuals with each other and with the social world.

Aglietta and Orlean (

2002) offer a sophisticated argument on how money creates social bonds that support trade and social relations but clouds the specificity of relations and commodities. In this heterodox view, money is sustained by organisations, laws and rules that represent the institutions of the monetary system, and rests on the trust that money will deliver the usual monetary functions. Authorities, namely the state but also other agents such as banks and merchants’ associations, participate in the process of structuring and imposing money over a sovereign territory, even by force if necessary (

Cohen 1999;

Wray 2004).

These two views leave us with a number of puzzles which are not specifically addressed. To start with, there are hardly any countries in the world in which the state´s monopoly of one currency in the whole nation is complete. In the last three decades over 50 countries have hosted numerous local and complementary currencies that attempt to improve the responsiveness and inclusiveness of the monetary system (

Blanc 2012,

2016;

Michel and Hudon 2015;

Seyfang and Longhurst 2013). These are often sustained by social agreements, with the occasional participation of state actors, and are considered “niches” (

Seyfang and Longhurst 2013). They may be more than niches, as Greece and Italy, two EU member states, are exploring the introduction of local parallel currencies in the form of tax anticipation scripts which would allow them to retain the euro for national and international transactions (

Bossone et al. 2015;

Théret et al. 2015). Finally, at the global level the state’s monopoly is being challenged by cryptocurrencies that facilitate counting and transferring value across borders and that enables an underground global economy. These trends suggest that the configuration of money, as a central economic institution, cannot be explained as the result of only central authority or practice. While money is normally established by states, it also circulates by simple practice, and sometimes these practices are contested or abandoned. How do economies go from these financial disruptions into new monetary practices?

An accepted definition of institutions, such as money, claims that they are “socially embedded systems of rules” that both constrain and enable social action (

Hodgson 2006). In that sense, they bridge individuals with the social world because institutions exist in the minds as well as “out there” (

Hodgson 2003;

Gomez and Ritchie 2016). Institutional theory offers two main understandings on the construction of institutions and these have been intensely debated among institutionalists such as

Kingston and Caballero (

2009);

Greif and Kingston (

2011);

Brousseau et al. (

2011) and

Hindriks and Guala (

2015). The two competing accounts on institutional configuration conceptualise institutions as rules versus institutions as evolved equilibria.

This article engages with money as an institution and takes a step further to explore the implications of understanding money in this way. How do money (or moneys) get established among economic institutions, what factors sustain it and why does it change? The article aims at presenting an empirically informed discussion of money as an institution drawing on insights from the two main strands of institutional theory. This paper combines the two theoretical perspectives on institutional emergence to analyse different categories and configurations of money. The study avoids a discussion on which one of the two conceptualisations of institutions is more appropriate but considers that both views highlight different aspects of the various types of money. There are moneys that have been centrally designed while others have evolved rather spontaneously. A critical implication of conceptualizing money as an institution is that they are bound to be contextually diverse (

Blanc 2016;

Gómez and Dini 2016;

Ingham 1998). The approach in this paper is different to the way other authors that have discussed money as an institution (for example,

Aglietta and Orlean 2002;

Wray 2004;

Arestis and Sawyer 2006) in unveiling the varieties of money and exploring the fact that monies are institutions of various kinds.

The discussion is grounded in an empirical case in which there are different monies, a phenomenon termed plurality of money defined by the concurrent existence of more than one type of money in a particular space (

Gómez 2018;

Kuroda 2008). Such a setting was found in Argentina in the period of 1998–2002, in which there were five different types of money circulating in the country at the same time (

Gómez and Dini 2016). In order to gain depth, the study will explain this scenario of monetary plurality in which sovereign money was centrally designed and other monetary practices came about spontaneously. It will later focus on the group of community currencies used by a total estimate of six million people around 2002. There were a few hundred of these currencies, created by grassroots organisations and generically known as

créditos.

The study is based on both primary and secondary data, including previous research and reports. The primary data was gathered during several periods of fieldwork between 2004 and 2013 and is part of a larger database that includes a multimedia collection, survey data, focus groups, and expert interviews. Three periods of fieldwork were carried out in 2003, 2004 and 2006 to gather data at the level of participants and the coordinators of 45 modes across the country. The initiators, the three founders of the initiative, academic experts and regional leaders were interviewed at the same time and later on in 2009 and 2013. Interviews were held individually and collectively several times in order to reconstruct its evolution based on oral history. A survey with a semi-structured questionnaire was carried out among participants and it resulted in 386 responses. The next section will discuss the two approaches to institutions, namely the institutions as rules and the institutions as equilibria. The third section will focus on the emergence of the bimonetary system in Argentina (pesos and U.S. dollars) and the fourth section will analyse the complementary currency systems created at the grassroots. The last section offers some further reflection in terms of resilience, responsiveness and stability of currencies.

2. Institutions: Rules or Practices

Money is conceptualized as an institution, a term that has a number of definitions. Douglas North provided the definition that has probably become the most frequently quoted one in scholarly work: “Institutions are the rules of the game” (

North 1990). Another Economics Nobel Prize winner, Elinor Ostrom, defined institutions in a similar way, as the prescriptions that are used to organize “all forms of repetitive and structured interactions” within communities, organisations, markets and so on (

Ostrom 2005). Indeed, all social interaction is mediated or regulated by institutions that indicate “the way we do things around here” as phrased by

Hall (

1986).

The origin of the social structures that create stability and continuity in society is a point of contention. At the risk of simplification, there are two main accounts on how institutions originate and how they change or resist change, and have been discussed by scholars such as

Kingston and Caballero (

2009);

Brousseau et al. (

2011);

Hindriks and Guala (

2015);

Hodgson (

2015) and others. Despite some variation among authors, a first strand that sees institutions as rules that come out of purposeful design.

Kingston and Caballero (

2009) refer to this view as the “centralized” or “designed” version, while

Hodgson (

2015) and

Greif and Kingston (

2011) refer to “institutions as rules” and

Brousseau et al. (

2011) use the label of “constraining rules”. In this strand, motivated agents express their preferences and negotiate, and exert pressure to push or block institutional changes according to their interests and benefit. The making of institutions is deliberate, centralized and assumes collective action because actors come together to bargain and make decisions or at times one exerts authority over others. In these negotiations, agents act according to their interests and in consideration of the existing rules. At the same time, negotiations are affected by authority and power asymmetries that favour the or voice or views of some decision-makers over the position of others. When it comes to institutional change, the focus is similarly placed on bargaining and consenting within the limits permitted or enabled by “rules of a higher order” (

Ostrom 2005). Additionally, some actors, like judges, have special roles to play in the change of rules because they pass new legislation or mediate as rule makers. These special agents are rather “autonomous drivers of change” (

Kingston and Caballero 2009, p. 158).

Critiquing this approach of institutions,

Kingston and Caballero (

2009) argue that rules may exist on paper but do not necessarily drive agents’ behaviour. Then, to what extent are those to be considered institutions at all?

Ostrom (

2005) distinguishes between “rules in form” (on paper) and “rules in use” (effectively observed), and the rules in form do not actually steer people’s behaviour. There are also rules that are observed but do not exist on paper, such as most informal rules which refer to culture. These are seen as adaptations to the context and to previous events, but without undergoing rational and consensual reform. They may become formalized, hence changing from rules in use, to rule in form.

A second strand of institutional theories underlines their evolutionary nature.

Kingston and Caballero (

2009) refer to them as “evolutionary”, while

Brousseau et al. (

2011) opts for the label “self-enforcing expectations”; and

Greif and Kingston (

2011),

Hindriks and Guala (

2015) as well as

Aoki and Hayami (

2001) prefer the term “institutions as equilibria”. According to this view, institutions appear in a decentralized and spontaneous manner out of repeated human interactions. Institutions depend and consist of repeated behaviour. There is no political process and no central instance that crafts the rules, but “uncoordinated choices of many individuals” (

Kingston and Caballero 2009, p. 160). The expectation or belief that an institution guides the actions of others is enough to keep agents behaving in a given way and in that sense they are considered institutions as equilibria. If there are alternative courses of action for a given situation, it is conceivable that several agents may behave differently while institutions “compete” with each other to dominate the actions of agents. In the long run, one course of action will prevail and that will become the equilibrium institution that is sustained by repetition, replication and imitation. According to this view, only rules in use in the Olstromian terminology are proper institutions. Change is already embedded in the idea of evolutionary change, which is slow and endogenous. There is no explicit agent to coordinate the decision-making or the institutional reform process, and the selection of the institution that stands would happen spontaneously and signals the “most efficient” or superior solution (

Williamson 2000).

Aoki and Hayami (

2001) explain that change occurs when a “general cognitive disequilibrium” happens, namely when an institution fails to obtain the expected results and when agents note a dissonance between the outcome obtained and the outcome expected.

Kingston and Caballero (

2009) identify this aspect in their critique: little attention is paid to explaining how and why a particular institution prevails and what this process of institutional competition looks like before it is resolved.

Williamson (

2000) claims that the prevailing institution is the most efficient one in reducing transaction costs and its survival can be taken as sufficient proof that this particular institution is the best alternative. Other authors, instead, resort to an explanation by partial or local equilibria that result when institutions are not placed in the same geography or time, so they would not be exposed to institutional competition but to geographical segmentation. Additionally, an institution may start locally and be adopted elsewhere but this assumes there is contact between groups. Other authors (for example,

Hayek (

1973) or

Greif and Tadelis (

2010)) link the selection process to competition among rival groups or leaders in which each group promotes its own solution to a certain problem or resists the institutions of another, among other reasons because those institutions are inconsistent with cultural norms or because of its distributional impact. In short, the account tells “an empirical success story” (

Williamson 2000, p. 607; quoted in

Kingston and Caballero 2009, p. 161). Once equilibrium has been established, there is little further theorization on what pushes agents to change the institution as equilibrium.

Money has been analysed as an institution by several authors (

Ingham 1998;

Gómez 2018;

Aglietta and Orlean 2006;

Blanc et al. 2016;

Dodd 2014;

Gilbert and Helleiner 1999;

Goodhart 2005;

Wray and Forstater 2006). However, such analysis has been done following strictly one of the two institutional perspectives presented in this section. There are a number of scholars that underlined the essence of money as an institution in which institutions are understood as rules (see for example,

Wray and Forstater 2006;

Aglietta and Orlean 2006;

Goodhart 2005). At the same time, there are a number of studies that highlight the nature of money as an institution which evolved as the belief that a certain thing has the capacity to perform the known monetary functions (for example,

Banerjee and Maskin 1996;

Kiyotaki and Wright 1989;

Selgin 2001). In both cases, there are empirical puzzles that remain unexplained. This paper proposes to analyse money as an institution which results from both centralised rules and as evolved beliefs. In the last years, there have been attempts by institutional scholars to combine both strands of institutional theory into a hybrid approach that conceptualizes “rules in equilibrium” (

Hindriks and Guala 2015). This means that as several solutions are available, eventually one appears as the satisfactory one and can be codified, i.e. summarized as symbolic representation. The authors follow John Searle, who distinguished regulatory from constitutive rules (

Searle 2005, p. 10), in which constitutive rules define status. Subsequent institutional change occurs by negotiation and centralized design, and includes the possibility that formal rules are nothing but endorsements of prevalent informal rules. In turn,

Brousseau et al. (

2011) focus on different temporal dimensions: institutions as rules concern the shorter term in which political negotiation and agreements are possible with a top-down approach, while the self-enforcing or equilibria account of institutions deals with the long term implied in social evolution and bottom-up approaches. In the meantime,

Hodgson (

2015) argues that rules include norms of behaviour and social conventions as dispositions to act in a certain way but with no certainty that behaviour will effectively and invariably follow. Effective behaviour is secondary to the existence of institutions, which are mainly a disposition to act.

Among scholars that study money as an institution, such combination has also been initiated.

Aglietta and Orlean (

2002, p. 35), for example, underline that money is an abstraction that depends on trust in the “supposition that money will always be accepted in trade by third parties”. Trust, the authors continue, is a relationship between each private agent and the community that uses a certain money. According to them, trust is not a contract, so “trust cannot dispense with regulation, or regulation with public authority”. So, “maintaining trust must be regarded as a regulatory problem of the utmost importance”. They further elaborate on this point by distinguishing three types of trust. The first one is methodical trust, founded on routine and repetition of actions. Methodical trust, they claim, “pales into insignificance before the furious rivalries unleashed by the power of money” and hence they distinguish a second type of trust, which is hierarchical trust. The latter is imparted by the political authority and they consider hierarchical trust superior to methodical trust because “the political authority over money has the power to change the rules”. The third one is ethical trust, which is an ethical attitude that reconciles conflicts and develops at the social level. It ascertains that a certain monetary order will maintain the value of private contracts over time.

Aglietta and Orlean (

2006) touch upon the distinction of money as an equilibrium sustained by methodical trust and regularity and consider that this type of money is inferior to money as rules that stems from centralized political authority and generates hierarchical trust. If there is any conflict between the two, it will be resolved at the loose level of ethical trust to protect social welfare and order. The authors hence incline themselves in favour of the state as the final decision maker on monetary matters. As it will be argued in the case of Argentina, the conviction that the state can induce such an ethical trust over methodical trust proves exaggerated. The next section will explore money as an institution from both approaches through the empirical case of Argentina.

3. Peso by Rule, Dollar by Practice

Simultaneous deficits in the external current account and the fiscal accounts were often met with policies that attempted to control both government spending and exchange rates at the same time (

Cortés Conde and Harriague 2006). But this could not prevent two-digit inflation rates from becoming normal. Some of these policies involved changes in the regulations on commercial and state-owned banks alike, as well as restrictions on the use of reserves and deposits, which undermined the credibility of the banking system in general. The combination of controls over the exchange rates, national inflation and low trust in the banking system created a parallel “black market” for foreign currency in which U.S. dollars were sold for more pesos than the restricted official exchange rate. Arbitration between the official and the black market dollar became a profitable business, while the U.S. dollar became the preferred currency to reserve value.

From an institutional point of view, the attempts of the central bank and other monetary authorities to control the key financial variables represent centralised and deliberate efforts to configure rules that organise economic life. The emphasis among the Argentine monetary authorities was placed on making the national currency a reliable unit of account, means of payment and reserve of value, while retaining control of the main financial variables in the hands of the state. However, institutions as rules depend on the capacities of the state or other authorities to enforce these rules. Inflation and instability undermined these capacities and actors such as the central bank and the Treasury, that were supposed to mediate the link between rules and effective behaviour, saw their capacities eroded by the poor performance of the Argentine money. In turn, this undermined other agents in the monetary system such as commercial banks.

By the end of the 1950s, high inflation and unstable business cycles introduced the practice of buying dollars as reserve of value and keeping them out of the banking system (

Canitrot 1981). Argentines gradually adopted the dollar as a second currency. Initially it was only a reserve of value but around the 1970s dollar-denominated prices gradually became common practice. The U.S. dollar became accepted in the transfers of goods such as houses and cars and long term contracts (

Gaggero and Nemiña 2016). By the 1980s, U.S. dollars were accepted as means of payment to trade most goods and services. In other words, the U.S. dollar was performing functions that national currencies do. The use of the U.S. dollar as second currency was not designed by any central authority but happened gradually, uncoordinated, spontaneously.

Muir (

2015) considers this behaviour especially prevalent among Argentine middle classes and contributed to the symbolic construction of the “small saver”.

The inflationary problem eventually derived in three hyperinflation periods between May 1989 and the end of 1990. Following that serious financial crisis, a monetary policy was launched that aimed at rebuilding the institutions regulating the relationship between Argentines and their money. It was introduced in March 1991 under the name of convertibility plan because the core policy was a currency board that pegged the peso to the U.S. dollar at a rate of 1 to 1. Equally important from an institutional point of view, the new plan allowed economic agents to open bank accounts, denominate prices or trade in U.S. dollars. In other words, the rule in use of adopting the U.S. dollar as unit of account and means of payment together with the official Argentine currency was formally adopted as a rule by the government. From currency in practice, the dollar became a currency as rule.

In the long run, inflation and a series of failed monetary policies contributed to form a peculiar understanding of money among many Argentines as a flexible social construction. Indeed, experience showed them that it can be transformed. In 1969 a new currency was introduced by law, changing 100 of the old circulating units for one unit of a new one. The measure did not work to stop inflation and was repeated in 1983, when 10,000 units of the circulating currency were changed for one unit of the new Argentine peso. That second reduction in the amount of digits was not effective either to regain trust and inflation eroded the value of the currency even faster. A third change occurred in 1985, when 1000 units of circulating Argentine pesos were changed for one unit of the new currency, named Austral. That currency vanished with hyperinflation, and it was replaced again in 1992 at a rate of 10,000 Australes for one new peso. In total, four changes of currency denominations scrapped thirteen digits off the unit of account between 1969 and 1992 (

Billetes Argentinos 2008).

The reforms in the currency reflect the difference between institutions as rules and actual behaviour. According to

Hodgson (

2006), rules are dispositions or injunctions to act in a certain way but do not establish behaviour per se. Indeed, the Argentine currency did not maintain its stability to serve as reserve of value, means of payment and unit of account. In the Ostromian terminology, the peso was partially performing as a currency in form and lost ground as currency in use. The U.S. dollar, instead, evolved as a currency in use, in the line of the approach of institutions as equilibria. It became accepted by the pervasive expectation that others would accept it too.

However, the official monetary authorities did not surrender their powers over the monetary system. As soon as the central bank regained some capacity to enforce rules, they tried to affect the bimonetary equilibrium and regain space for the official currency. Following another financial crisis with capital outflows, the Argentine government imposed a series of restrictions on the currency exchange in force between 2011 and 2015. The regulations restricted the rights to buy foreign currency and were difficult to impose because it implied the government could effectively distinguish who wanted foreign currency as reserve of value and for other purposes. The measures recreated a black market for foreign currency and were gradually relaxed until the new government abandoned them completely in December 2015.

Luzzi and Wilkis (

2018) discussed the implications of this attempt of the official monetary authorities to regain their sovereignty over the currency in Argentina. Despite the regulations to “domesticate” it, bimonetary practices presented a remarkable resistance to change. Resilience is a key element of the conceptualisation of institutions as equilibria. In the terminology proposed by

Brousseau et al. (

2011), bimonetarism evolved as an institution and was not only resistant to change but also self-enforcing by mutual expectations. However, the restrictions cannot be considered a complete failure, highlighting that this competition between two currencies is not a normal monetary practice in other countries and has social costs.

4. A Hybrid Institution: Community Complementary Currencies

It was mentioned above that in 1995 the currency board system was challenged by an international financial crisis that started when Mexico devalued its currency. The Argentine economy adjusted by deflation and recession which in turn translated into a loss of jobs and income. Unemployment had risen gradually throughout the 1990s, but in 1995 the unemployment rate hit 18.8 per cent. Used to the term “hyper-inflation”, Argentines were introduced to the term “hyper-unemployment” when media and experts used the word to describe the new situation. The purchasing power of wages in 1995 fell to 68 per cent of their 1986 level and 62 per cent of their 1975 level. Another term that became common around that time was that of the “new poor” to describe households that had fallen under the poverty line for the first time. Only a decade earlier, 70 per cent of the Argentine population had declared itself to be part of the middle class (

Minujín and Kessler 1995). The new poor were the shopkeepers, public servants, skilled workers, graduates, blue-collar workers, bank clerks, teachers and small-firm owners, among others whose basic needs were covered who could no longer afford their lifestyle.

Amidst this environment of economic demise, civil society organisations launched a number of small-scale bottom-up initiatives to reorganise social life at the community level (

Gomez 2009;

Gómez and Dini 2016). Among them was the Club de

Trueque, a circle of neighbours that exchanged goods and services with each other and was launched in May 1995. The informal exchange of goods within a closed network of impoverished middle-class members was initially carried out in one organiser’s garage. Participants offered care services, home-made foods, handmade toiletries, organically-grown vegetables in their gardens, and all sorts of handicrafts. After six months of testing different methods with 25 to 50 participants meeting every Saturday, the group developed an exchange system that they found to be effective and practical. Participants came into the garage and placed their products on a table. The value was calculated at the formal market prices and was recorded on individual cards carried by the participants and on a computer worksheet. When the value of everyone’s products had been recorded, participants turned to the role of consumers to choose what they wanted to take. The value of their acquisitions was deducted from the amount on their cards. Thus, the higher the value of the products brought, the more the producer would get of other people’s products. Any producer who did not agree with the price given to a product was free to withdraw it, but that hardly ever happened. When people thought the price was low, they viewed it as a partial gift to others, which they would recover some other time when they obtained something below the regular price. When they left, their sales and purchases were entered as debits and credits on a computer worksheet. The overall balance roughly returned to zero every week. The remaining credits and debits were transferred to the following meeting. The system emulated a closed market in which exchanges were multireciprocal, so two individuals did not need to coincide with each other directly. The payment system was a novelty- it was not based on bartering or making payments through a basic commodity but was based on mutual credit/debts in an accountancy system.

It quickly became clear to the organisers that book-keeping on the basis of individual cards and computer records was hitting a limit. The organisers felt that entering transactions into the computer file was too burdensome and time consuming. Besides, they did not like the centralisation inherent in the system. “I was at the centre and we didn’t like the idea of centres. As ecologists, we believed in autonomous self-regulation, like the environment is. The cards were blocking the potential of the scheme” (Interview with an initiator, Bernal, 13 June 2004). The successful propagation of two more nodes made the limitations of the individual card accountancy system more evident. Moreover, participants often travelled considerable distances to participate in the Trueque market, which means a waste of time and money. One of the organisers then got an innovative idea to facilitate the payments. He recalled, “One day I was walking by a print shop and saw their business cards. Then I thought, ‘Why don’t we just make vouchers that can circulate among the members to pay each other?’ We could just print them, right? So we went into the shop and asked the shopkeeper to make us some notes”. The others liked the idea of using vouchers as means of payment because of its practicality and because it removed them from the centre.

The scheme was so successful that it grew and the original organisers replicated it in the locations of friends and contacts across the city of Buenos Aires, at first, and the rest of the country, later on. Surrogate currencies were instituted in each

Trueque node. Every new participant received a credit of fifty créditos so they could start trading, but they were committed to giving them back if they left the group. In comparison with the card system, physical notes were easier to handle. Organisers and participants alike assure that nobody perceived the vouchers as money but as the system grew, it slowly dawned on them that the vouchers were a social type of money. Anyone in the

Trueque would accept the notes, but they were normally not convertible to pesos. By all means,

Trueque created an institutional equivalent of what is considered money in modern economies. It was an abstract means of payment, depersonalised, dematerialised, transferable promise to pay (

Gomez 2010;

Gonzalez Bombal 2002;

North and Huber 2004). The créditos were printed in denominations following those of the formal economy. Not surprisingly, the money was called

crédito, indicating that members “gave credit to each other because we trust everyone here” (Interview with initiator, Bernal, 6 September 2004).

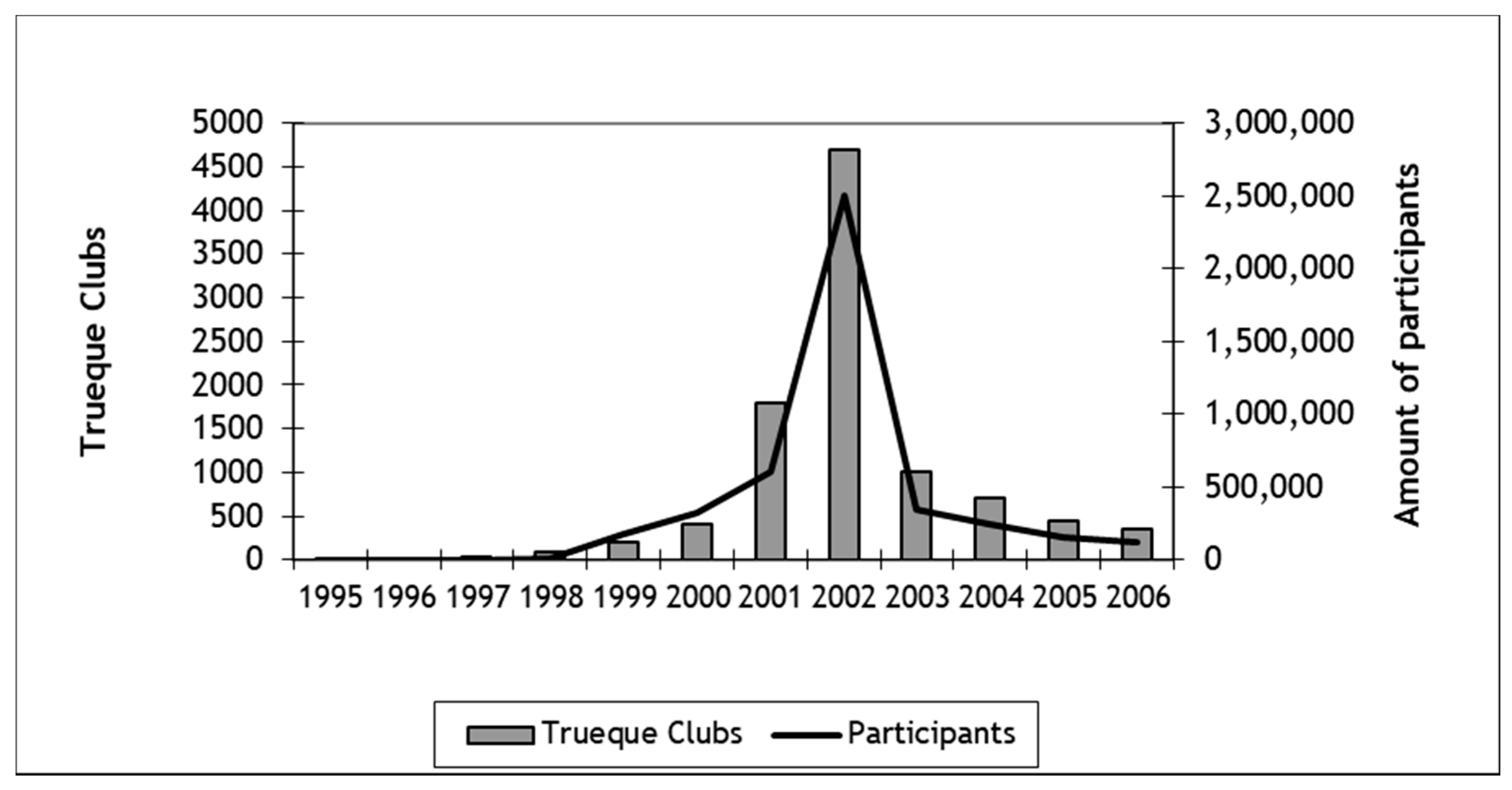

In the middle run, complementary currency systems (CCS) printed by grassroots organisations emerged at the local, regional and national levels. The initiative kept replicating, hence forming regional and national networks, together with umbrella organisations that kept them interconnected or steered replication rather hierarchically. The

Redes de Trueque turned out to be the largest experiment with a complementary currency system in the world in modern times. According to unofficial figures, by the beginning of 2002, with the regular economy melting down, the

Redes de Trueque reached a peak of 2.5 million participants in 4700 centres across the country (

Ovalles 2002). There are no official statistics that would allow a more accurate estimation of how large they were and what their exact impact as an anti-cyclical device was. An indicative estimation is presented in

Figure 1, which combines data from several sources and is meant only as an indication of their scale.

Colacelli and Blackburn (

2009) have a small and partial dataset that would corroborate these figures in the location where they gathered data.

In terms of the modern monetary practice of ‘one country, one currency’, the creation of a currency system of the scale of the Trueque is a real anomaly. It is clear that an economic demise that chopped 20 per cent of the GDP contributed greatly to the phenomenon. However, other countries in recent decades have had similarly severe economic downturns and their monetary system stuck to one currency. The

Trueque calls for a broader explanation to bring new insights into the origins and meanings of money. In relation to the extended complementary currency systems in the U.S.A. and Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, the main difference was organisational: the

Trueque was structured in regional and national networks articulating local markets. Each one issued its own currency, which was normally accepted in other neighbourhoods and networks too, so it was possible to pay for goods and services with the same scrip across the whole country. For some time, there was an umbrella organisation checking each other’s currency systems; before and after its existence, scrip was accepted simply out of trust in the system. Similar integration has been attempted less successfully on a regional level in places like Manchester, UK, but with limited success (

North 2006). Nowhere has an attempt been made to create a national, private, yet not-for-profit monetary system as the

Trueque.

In the longer run, the use of community currencies promoted the launch of new small businesses that could learn their trade in a protected market, and helped the unemployed to survive their disenfranchisement and return to regular jobs when the economy recovered. Thus, the institutions of the community currency systems were clearly responsive, but they proved not to be resilient. With several million participants, it had grown beyond the scale in which it was appropriate to “trust everyone here”; shirking and opportunistic behaviour became rampant. The institutional weaknesses of the Trueque became evident at exactly the same time as the regular economy started a period of vigorous recovery, and within a year, by 2003, they collapsed to about a fifth of their peak size. Still, the fieldwork done in 2013 proved that the Trueque did not disappear completely but became much smaller.

Are complimentary currency systems institutions as rules or institutions as equilibria? On the one hand, the

Trueque had been established by deliberation, negotiation and agreement along the lines described in the institution as rules approach. The leaders and organisers performed the role of “autonomous drivers of change” as described by

Kingston and Caballero (

2009, p. 158). They discussed and made a myriad of decisions at different levels, including the design and name of the currency, the amounts to print, the methods to distribute it among existing and new members, and the participants that would be allowed to join and would be required to follow these procedures. The leaders kept reframing and improving the scheme, while the number of participants soared. They had to decide on the institutions to guide the behaviour of participants, setting rules for who was allowed to join, what was acceptable and what was not. The collective action process by which institutions as rules were made proved to be complex and exhausting, yet rules were made. The outcomes of these negotiations were institutions as rules that regulated the actions of members who had voluntarily accepted to abide by them. There was a clear and open commitment in the community to abide by the rules, which is an additional factor theorized by

Gilbert (

1992, p. 197) as the common understanding that under certain conditions people are jointly bound to pursue a certain action as long as they all do the same action. At the same time, the leaders had insufficient means to enforce the rules and sanction trespassers. They could not prevent massive forgery of the currency, abusive behaviour with prices and widespread speculation. They had created institutions as rules that did not always translate into effective action in the long run, as it happens with so many other institutions as rules created at the grassroots level. Eventually, the collapse of the

Redes de Trueque does not undermine the significance of these complementary currencies that performed as units of account and means of payment among thousands of Argentines for about a decade (

Gomez 2010;

Plasencia and Gutierrez 2006).

On the other hand, the complementary currency systems show traits of evolved institutions. The growth from one small and local

Club de Trueque to a complementary currency system of over 2.5 million members took place without centralised and deliberate design. Groups across the country spontaneously imitated and replicated the initiative across the country. There was no coordinated planning such as, for example, where to locate them, but barely copying and replicating what other groups were doing nearby. Participants in one

Club de Trueque would often learn the rules and get the idea to launch one in their neighbourhood. They obtained information and know-how on how to run one informally by word of mouth, through the media, by contacting an organiser in their own personal networks or simply learning by doing. The expansion of the

Redes de Trueque around every corner is mainly a tale of evolved institutions that spontaneously disseminated the initiative by gaining ground from the failing official currency. Since there were no legal regulations supporting them, they were primarily self-enforcing institutions, according to the terminology suggested by

Brousseau et al. (

2011).

In terms of institutional theory, the complementary currency systems present a puzzle: they cannot be conceptualised as either institutions as rules or institutions as equilibria. It would be easy to dismiss them because they were relatively small and collapsed in the end but they existed long enough and reached a scale that merits a more elaborate explanation. The Argentine complementary currency systems show characteristics corresponding to both institutional narratives. However, they did not prove their resilience in the longer run and collapsed quickly. A note should be added about their responsiveness, and that is that they continue to exist in some locations, away from the public attention and the media. Moreover, they tend to reappear as soon as recession or a new financial crisis dawns in the horizon

5. Reflections

This paper has analysed the plurality of money in Argentina arguing for the use of plurals to refer to institutions and moneys. To move forward and analyse the implications of understanding moneys as institutions in the event of a new financial crisis, the discussion required a clear conceptualization of money as an institution. At the risk of overgeneralizing, there are two prevalent approaches to institutions, namely as rules and as equilibria. The first one focuses on centralized design, bargaining and authority to establish rules of use and form. The second one defines institutions as equilibria and underlines their evolutionary nature with a period of competition after which one outcome prevails and remains in equilibrium. Is money an institution as rule or an institution as equilibrium?

Research discussing these two narratives on institutions has not resorted to empirical explorations. This article presents an empirically informed discussion of money as an institution drawing on insights from the two main strands of institutional theory, while it avoids an evaluation of which one is more correct. It has discussed the issues of resilience and responsiveness of the currencies, the role of centralised monetary authority and the means of enforcement or self-enforcement that make the monetary institutions stable in the longer run. In a nutshell, the national sovereign currency of Argentina, the peso, emerged within the formation process of the nation state in the 19th century. Throughout the 20th century the imbalances in the Argentine economy undermined the performance of the monetary system, including episodes of hyper-inflation, poor performance of the functions of money, low trust in the central bank and other monetary authorities, and a generalized weakness of the banking system. The formal institution of money as a rule did not perform in reality all the functions that are expected of money. Gradually, the population adopted the U.S. dollar as unit of account and reserve of value, and later on also as means of payment, so Argentina became a bimonetary economy. The emergence of the U.S. dollar as an alternative further undermined the long-term credibility of the peso as the national currency sustained by the state, i.e. the currency as rule. In turn, various failed efforts to rescue the functionality of the national currency diluted the legitimacy of the monetary authorities to impose a national currency.

Contrary to the claim by

Aglietta and Orlean (

2002) that hierarchical trust (by state regulation) is superior to methodical trust (by evolved regularity), the Argentine case suggests that use of the U.S. dollar as an institution in equilibrium has proved self-enforcing, extremely resistant to change and defiant of the state’s authority. Methodical trust has resisted the monetary authorities’ determination to win the wrestle between its centrally designed currency (the peso) and the spontaneously adopted currency (the U.S. dollar). At the same time, the phenomenon of bimonetarism has not been responsive to the demands for social change and inclusiveness of some sectors of the Argentine population.

A third type of currency was widespread between 1995 and 2005. The Redes de Trueque were born small, and spread fast across the country. These community currency systems were launched during a financial crisis and had their greatest expansion during the economic meltdown around the turn of the millennium. They represented a hybrid category between institutions as rules and institutions as equilibria and exhibit traits of both approaches. That is, they were centrally designed and sustained by grassroots organisations while they expanded rather autonomously across the country by the copying, imitation and replication of local initiatives. The case of the Redes de Trueque also suggest that the centralised design of institutions as rules is time consuming and requires a myriad of decisions and agreements to make them work, even if this is partial and lacking the means to sanction trespasses. As there are various types of money, the article refers to money as institutions, in its plural forms, because spontaneous evolution and centralized design do appear together in different combinations to generate money. Monies such as complementary currencies are hybrids between institutions as equilibria and institutions as rules.

The expansion of the complementary currencies was sustained by need and the crisis of the regular economy, so they were clearly responsive but did not prove to be resilient and collapsed after a few years. They could not resist the combination of opportunistic behaviour and the recovery of the regular economy and these institutions fell into demise. In a nutshell, they expanded rather autonomously in a decentralized manner, and they collapsed in competition with the regular economy and its money as rule. These institutions as rules had been agreed at the central level of the Redes de Trueque, so they expanded by belief and expectations and collapsed by disbelief and negative expectations. In comparison with the use of the U.S. dollar as evolved institution, the complementary currency systems could not be seen as having reached long term equilibrium. While the Argentine state failed to regain the exclusivity of the national currency in the monetary system against the U.S. dollar, in the case of the complementary currency systems the state did not need to take exceptional measures to reduce them. The question which begs to be asked is how long does an institution need to be in equilibrium to become a rule, or viceversa, how long does a rule need to be enforced until it becomes self-enforcing?

This discussion offers tools to rethink bimonetarism, not by continuing what seems a lost battle against the endogenously adopted currency (U.S. dollar) but by designing additional features on this institution as equilibrium in order to move towards a hybrid. Such policies would have higher chances of success because they would not be fighting against what is already a resilient and established practice. At the same time, it suggests working on strengthening the institution as a rule, the peso, in search of a hybrid that would keep both currencies but with more elements of the centrally designed institution that exist at present.