1. Introduction

Due to the global financial crisis, many Japanese companies fell into difficulties and had trouble repaying debts. Accordingly, the Japanese government enacted “the Act on temporary measures to facilitate financing for small and medium-sized enterprises” (hereafter, the SME Financing Facilitation Act) in 2009. Under this law, when debtors asked financial institutions to ease repayment conditions (e.g., extend repayment periods or bring down interest rates), the institution would have an obligation to meet such needs as best as possible

1.

After the law was enacted, it was said that financial institutions were very flexible in complying to the changing of conditions. However, because financial institutions were lightly complying to the request for changing loan conditions and were not making serious efforts to support revitalization, there is criticism that it did not become an opportunity for companies to substantially reform their businesses, and that there was moral hazard on the company’s side (e.g.,

Hoshi 2011;

Harada et al. 2015;

Imai 2019). That is, companies that were allowed to change loan terms were likely to feel that financing could be managed in the short-term, and so they did not work towards reforms in earnest.

This paper uses the “Financial Field Study After the End of the Financing Facilitation Act” carried out by the “Study Group on Corporate Finance and Firm Dynamics” of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI), to analyze whether the performance of companies is recovering after changes to repayment conditions. It also looks at what kind of differences there are between companies that are recovering and those that are not. As explained later, the survey was very unique in that it included many firms that requested loan condition changes. We found that about 60% of companies whose loan conditions were changed recovered their performance after the loan condition changed. Also, we found that the attitude of financial institutions towards support was a major factor in whether firms could recover after loan condition changes. Although previous studies negatively evaluated the act, our finding suggests that the act may be effectual if financial institutions make an effort to support troubled firms. Although this kind of policy was unique to Japan during the global financial crisis, all nations will be able to employ it to cope with a future crisis in a wisely manner.

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 will explain the impacts of the global financial crisis on Japanese firms and what the Financing Facilitation Act was.

Section 3 provides the literature review.

Section 4 will introduce an outline of the “Financial Field Study after the End of the Financing Facilitation Act”, which is used in this study.

Section 5 will analyze how much companies recovered their performance after they received changes to their repayment conditions and what kind of factors caused this. Finally,

Section 6 will present the conclusions of this paper.

2. The Global Financial Crisis and the Financing Facilitation Act

2.1. Impacts of the Global Financial Crisis on Japanese Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs)

The global financial crisis severely hit Japanese firms.

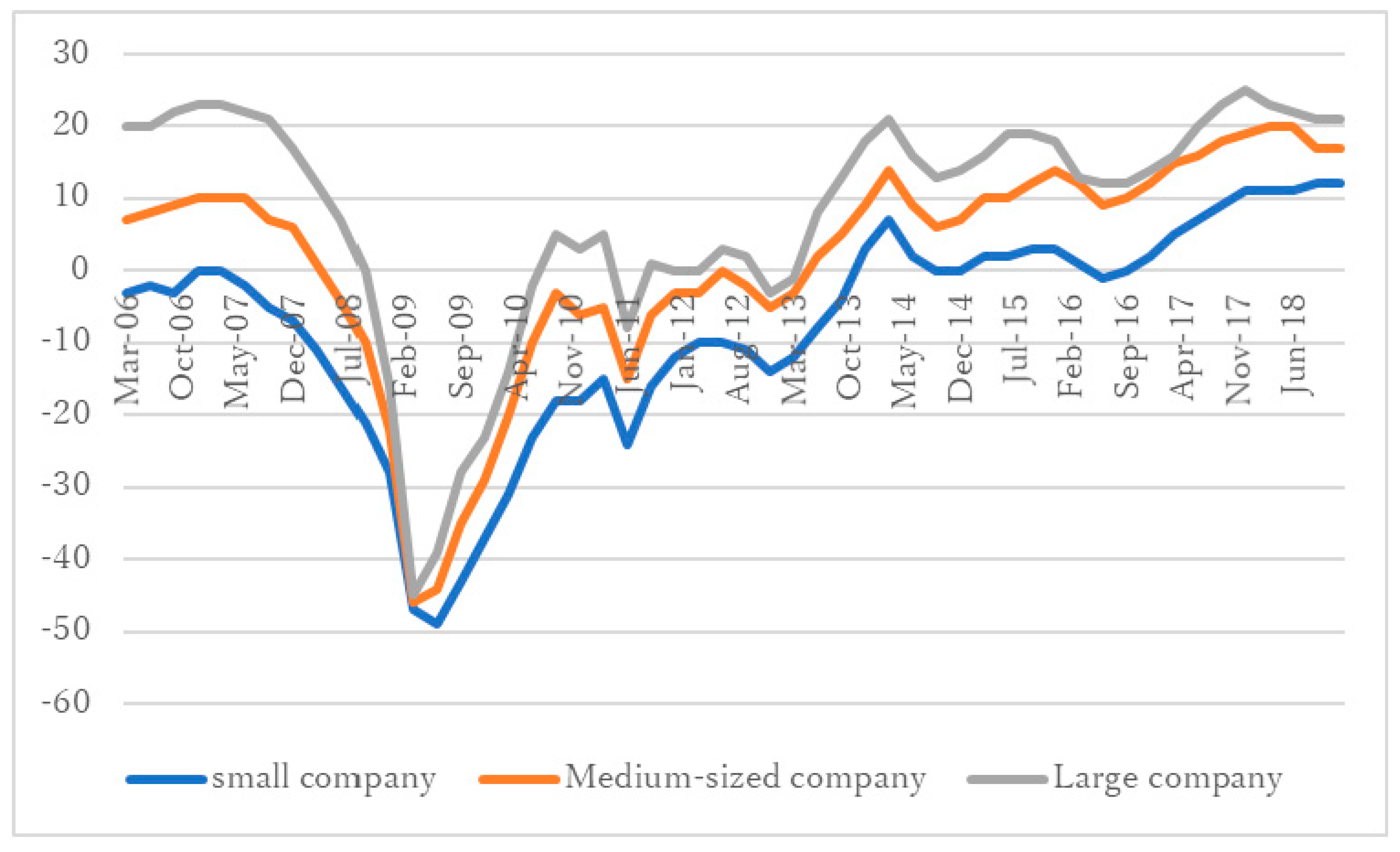

Figure 1 shows how business conditions of Japanese firms deteriorated during the global financial crisis, irrespective of their size. For example, business conditions diffusion index (BCDI) for large firms was 23 in March 2007 and decreased to −45 in March 2009. The index for small firms decreased from 0 to −47 during the same period.

Also, as shown in

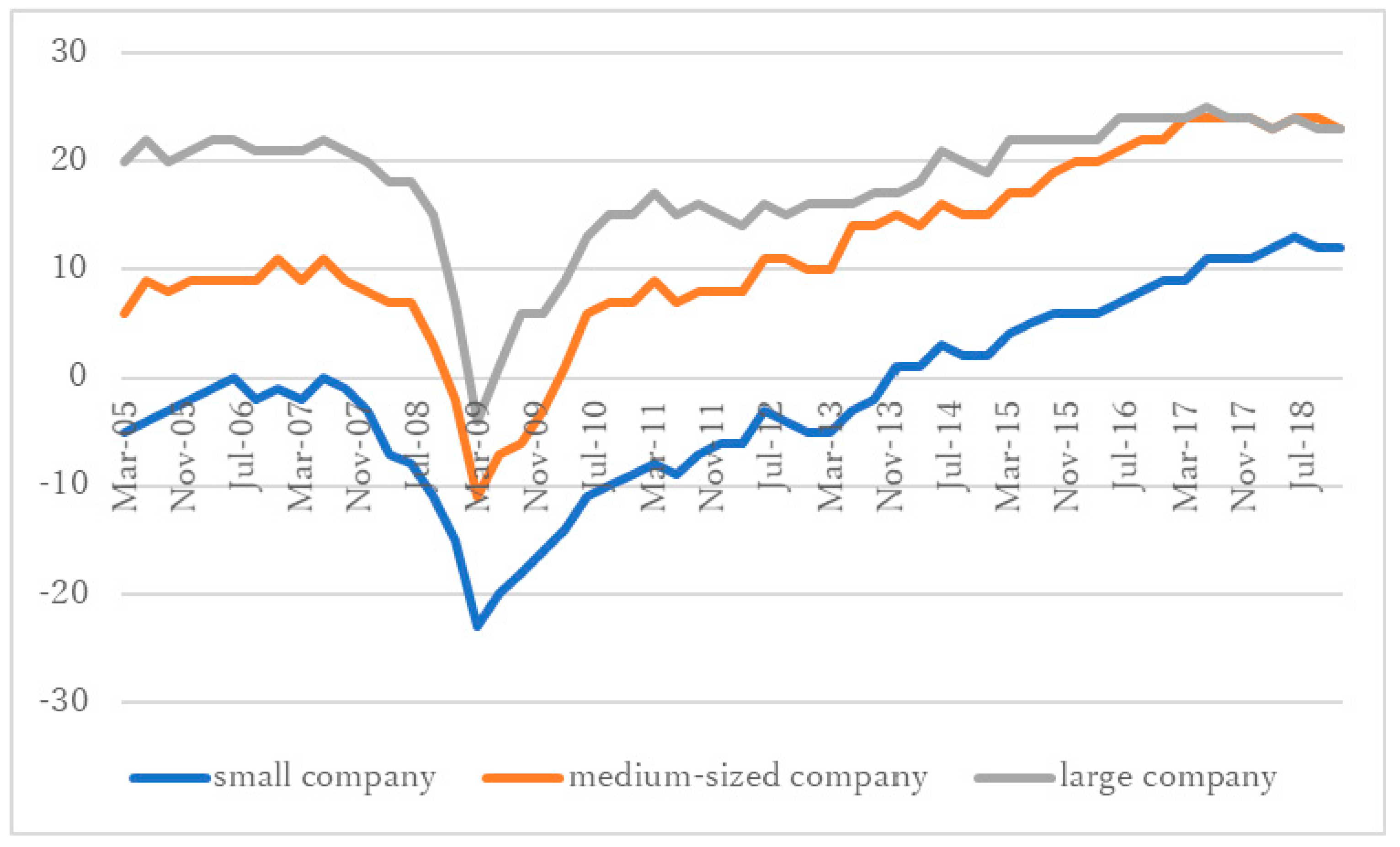

Figure 2, during the global financial crisis, funding conditions of firms significantly deteriorated. Funding conditions diffusion index (FCDI) for large firms was 21 in March 2007 and decreased to −4 in March 2009, while the index for small firms decreased from −2 to −23 for the same period.

To accommodate the difficulties that firms faced, the Japanese government introduced various supportive measures (

Bank of Japan 2010;

Yamori et al. 2013;

Harada et al. 2015). The Financing Facilitation Act, which is the main topic of this paper, was unique to Japan and was negatively criticized.

2.2. The SME Financing Facilitation Act

In November 2009, the SME Financing Facilitation Act was passed. According to the Financial Services Agency (FSA), the act had the following contents

2. First, when requested by an SME or a residential mortgage borrower to ease debt burden, financial institutions such as banks, Shinkin banks, and credit cooperatives strived to revise the loan terms, etc. Second, financial institutions were obliged to (i) develop internal systems for fulfilling the above responsibilities of financial institutions, and (ii) disclose information on implementation of the responsibilities of financial institutions and the development of internal systems. Third, financial institutions were obliged to report information on their implementation to supervising agencies. False statements in the report were subject to criminal penalty. Fourth, authorities summarized the reports from financial institutions and published the summary on regular basis.

At the same time, the Financial Supervisory Agency amended the Supervisory Guidelines. As pointed out by

Harada et al. (

2015), the important amendment was that banks could exclude the restructured SME loans from non-performing loans if they planned to come up with restructuring plans that were expected to make the loans perform in five years from the time they specified the plan.

In sum, the act encouraged banks to roll over loans to troubled SME borrowers when they were asked

3. Although there was no penalty provision when banks did not follow the “best efforts” requirement, almost all requests by troubled SMEs for loan restructurings were admitted.

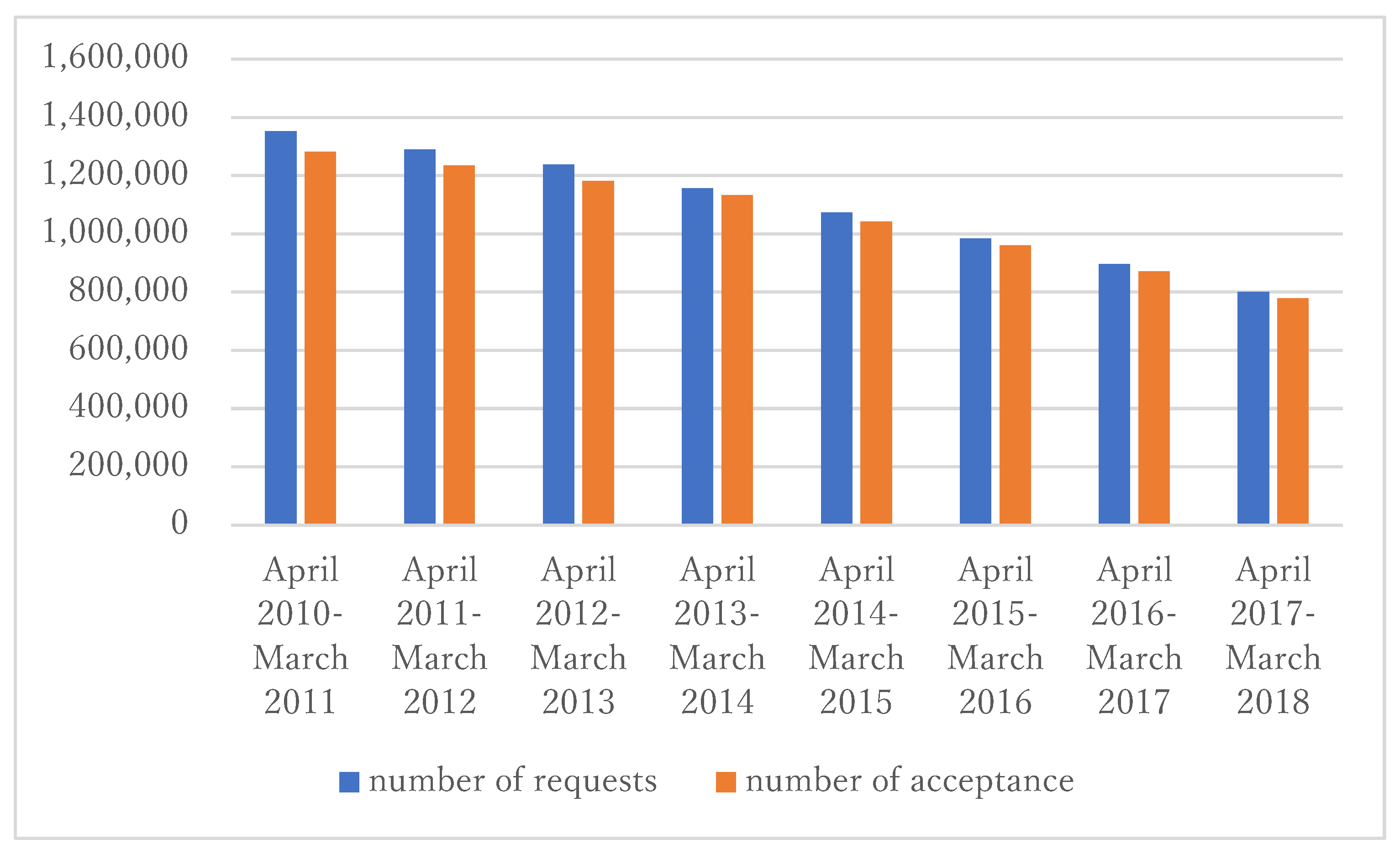

Figure 3 shows the number of requests by SMEs to change loan conditions and the number of those that were accepted by banks. The acceptance rate was 94.8% for the period from April 2010 to March 2011. The act was originally set to expire at the end of March 2011, but it was extended twice before finally expiring at the end of March 2013. Therefore, as explained below, our survey was conducted after the expiration of the Financing Facilitation Act. The acceptance rates continued to exceed 95% after April 2013. Namely, Japanese banks are likely to accept requests of troubled SMEs to change loan conditions easily, even though the law formally expired.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Impacts of the Global Financial Crisis on SMEs

How governments around the world have responded to the crises and how their responses affected the performance of small firms is relevant to academics and policy-makers. The impacts of the global financial crisis on non-financial firms have been investigated actively.

Claessens et al. (

2012) conducted cross-country analyses covering 42 countries and found that the crisis had a bigger negative impact on firms with greater sensitivity to demand and trade, particularly in countries more open to trade

4.

Kremp and Sevestre (

2013) investigated French SMEs after the global financial crisis. They found that French SMEs did not appear to have been strongly affected by credit rationing since 2008.

Zhao and Jones-Evans (

2017) analyzed the impacts of the global financial crisis on SMEs in the UK.

There are several papers investigating the impacts of the global financial crisis on Japanese SMEs.

Yamada et al. (

2018) used 764,963 SME observations in Japan and analyzed how the global financial crisis related to the investment and financial decision-making for SMEs. They found that the effects were different among SMEs. For example, firms without debt increased their investments during the crisis period, while SMEs with a high amount of debt at the pre-crisis period additionally borrowed more money from financial institutions but did not use it for investment.

Ogawa and Tanaka (

2013) used data from a unique survey that was conducted by the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) in 2008 and 2009. They found that the bank-dependent SMEs asked their closely-affiliated financial institutions for help, while the SMEs that were less dependent on financial institutions sought help primarily from their suppliers.

3.2. Literature Relating to the Financing Facilitation Act

Harada et al. (

2015) attempted to evaluate the financial regulatory responses (i.e., Basel III, stress tests, over-the-counter derivatives regulation, recovery and resolution planning, and banking policy for SME lending) by the Japanese government after the global financial crisis. They critically argued about the Financing Facilitation Act, because the act enabled troubled SMEs to ask for loan restructuring and banks to grant loan restructuring for almost all who asked. In other words, the act allowed the so-called zombie firms to survive

5. They pointed out that relaxation of bank supervision in conjunction with the act allowed banks not to report these loans as non-performing loans. Furthermore,

Imai (

2016) showed that zombie firms were prevalent amongst small and medium-sized firms, and that their investment projects were not as productive as non-zombie firms.

Based on these findings,

Imai (

2019) concluded that it was safe to say that the Japanese government’s forbearance policy benefitted weak banks and their unviable borrowers at the expense of the public. Following this context,

Imai (

2019) regarded the Financing Facilitation Act (which they called “the debt moratorium law”) as an example that Japanese government reverted back to the habit of using its discretion to soften prudential banking regulation after the Lehman shock.

Imai (

2019) pointed out “the debt moratorium law might have mitigated credit crunch for SMEs”, but the law “has again created a regulatory environment in which zombie firms tend to thrive, just as the forbearance policy did in the 1990s”.

In sum, these previous studies emphasized its problems. However, as the act surely mitigated the negative impacts of the crisis on SMEs, it seems useful to investigate how to enjoy its benefits while avoiding its negative effects. As far as we know, there are few studies that are focusing on the positive side of the Financing Facilitation Act and consider how to use it wisely.

4. An Outline of the Financial Field Study after the End of the Financing Facilitation Act

Recently, many SMEs studies have obtained data through surveys (e.g.,

Uchida et al. 2008,

2012;

Ogawa and Tanaka 2013;

Wang 2016;

Xiang and Worthington 2017). For example,

Kraus et al. (

2012) used survey data gathered from 164 Dutch SMEs and investigated how entrepreneurial orientation affected the performance of SMEs during the global financial crisis. Research using questionnaire data is increasing because macroeconomic data alone cannot provide sufficient analysis. First of all, small and medium-sized enterprises are diverse, and the impact of shock varies by company. Policy responses need to be tailored to the conditions of each company, which requires an analysis that reflects the attributes of various SMEs. Second, in order to understand the behavior of SMEs, it is necessary to take into consideration not only quantitative data such as sales and profits but also subjective factors such as anxiety about business conditions and funding.

Therefore, survey data analyses are valuable in understanding the merits and demerits of the Financing Facilitation Act. Fortunately, the author is a faculty fellow of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) and can access the dataset that was developed by the RIETI. We can use in this paper the “Financial Field Study after the End of the Financing Facilitation Act”. This study was carried out from October to November 2014 by the RIETI

6.

The survey sample used by the study was an extract from the Tokyo Shoko Research (TSR) database of 20,000 small and medium enterprises that existed as of both December 2009 and October 2014, the latter being when sample extraction work was conducted. Specifically, it consisted of the following three samples.

The first sample had the objective of gathering together “treatment companies” that received changes in loan conditions along with the enforcement of the Financing Facilitation Act. Tokyo Shoko Research (TSR), a major Tokyo-based credit research company, delivers credit reports on a wide range of SMEs, and we found that the reports of 4087 enterprises included the keywords “condition changes” or “facilitation act”. As these firms were likely to apply for the changes in loan conditions, we included them in our sample. The second sample had the objective of gathering together “control companies” as opposed to “treatment companies”, and consisted of 5207 companies that answered the survey of “The FY2007 Field Study of Transactions with Companies and Financial Institutions” carried out by the RIETI in February 2008

7. They were included because they were expected to respond to our survey with a high probability. The third sample had the objective of gathering additional “treatment companies” and consisted of 10,706 entries of companies with a TSR creditworthiness grade of 49 and under (in other words, companies with severe business conditions) and that had a distribution of employee numbers similar to the second sample.

Upon sending surveys in October 2014 to 20,000 companies selected based on the above standards, valid answers were received from 6002 of them, a response rate of 30.01%. Responses from the first sample numbered 996, with 2537 from the second sample, and 2465 from the third.

The average employee number of the companies that responded, as of the time when the Financing Facilitation Act was enforced (December 2009), was 61.33 employees and the median was 24 employees. More specifically, 598 or 10% of companies had “between 1 and 5” employees, 2135 or 36% had “between 6 and 20”, and 1478 or 25% had “between 21 and 50”. Thus, approximately 70% of companies had employee numbers 50 and below.

Table 1 summarizes the basic statistics of respondents for the latest business year

8. Average total assets and net-worth were 2478 million yen and 751 million yen, respectively. Average number of employees was 68, which was slightly larger than the figure in December 2009. As shown by the difference between the median and the average, a few very large companies were included in this sample, but most of the sample firms were SMEs, which were generally more vulnerable to economic shocks and more dependent on financial institutions.

5. Results

5.1. Changes in Loan Condition Changes after the Financing Facilitation Act

In the “Financial Field Study after the End of the Financing Facilitation Act” (hereon referred to as “this study”), the following question was asked with five answer options: “Since the Financing Facilitation Act was enforced (December 2009), had changes in loan claim repayment conditions been permitted even once for your company?”

Table 2 shows the results of this question.

As mentioned before, there were a total of 6002 companies who responded to this study, but those who responded as to whether there were changes to their payment conditions or not were 5621. According to

Table 2, the number of those companies that had their condition changes permitted (which are referred to below as Changes-permitted companies) was 1561. On the other hand, 3717 companies answered that “We didn’t apply for it as we didn’t feel it was necessary” (referred to below as Changes-unneeded companies). It is notable that the Changes-permitted companies made up a 28% share, due to the sample gathering method of this study, which did not suggest that about 30% of Japanese firms received loan condition changes during the global financial crisis.

5.2. Changes in Business Performance from the First Changes in Loan Conditions to the Present

This study asked about the change in business performance after the first changes to conditions up until the present, using a 5-level answer scheme (from “improved” to “worsened”).

Table 3 shows these results. Of course, the target for this question was only companies that had condition changes permitted (1561), but 1497 of these firms provided valid answers. Thus, these 1497 companies were the main target of the analysis in this paper, and for reasons of comparison, the results of Changes-unneeded companies were mentioned when necessary.

Looking at

Table 3, “Improved” and “Slightly improved” (both referred to below as the combined term

improved trend) took up approximately 60%, while “Slightly worsened” and “Worsened” (both referred to below as the combined term

worsened trend) took up just under 20%. Thus, there have been positive developments in business performance after the changes in loan conditions. The loan condition changes are regarded as an effectual measure to support temporarily underperforming firms and to keep them afloat. On the other side, we should pay attention to the fact that around 20% of companies did experience the

worsened trend. It is very important to bring down this percentage in order to reduce costs caused by this kind of policy measure in coping with a similar crisis in the future.

For this purpose, this study intends to examine the causes of

Table 3’s differences in improvement in business performance after conditions were changed.

5.3. An Overview of Companies That Had Their Loan Conditions Changed

5.3.1. Employee Numbers

Table 4 shows the number of full-time employees by five categories of changes in business performance. The median for companies where performance was “Improved” was 33 people, and “Improved” companies were larger than companies of other performance categories.

In this study, employee numbers at the time of the condition changes were not inquired about, so we were unable to verify directly how they had grown since the first changes to payment conditions. However, we inquired about both the employee numbers of the latest accounting period and those from two periods before, and so we knew fluctuations in employee numbers through this one-year period. On investigating this, it can be seen that “Improved” companies increased 1.01-fold, “Slightly improved” stayed the same at 1.00-fold, “Didn’t change” decreased 0.98-fold, “Slightly worsened” by 0.95-fold, and “Worsened” by 0.91-fold. In other words, companies with an improved trend increased employees, while companies with a worsened trend had a roughly 10% reduction in staff across the recent one-year period.

5.3.2. The Current Business States

This study asked companies about several aspects of their business states, such as their current business performance and finances, by using a 5-level answer scheme (from “Good” to “Bad”). Here, 5 points were assigned to companies answering “Good”, 4 points was “Slightly good”, 3 points was “Normal”, 2 points was “Slightly bad”, and 1 point was “Bad”. With these calculations, companies with larger numbers were meant to be in better condition.

Table 5 shows those averages.

According to

Table 5, the average “Improved” company had over 3 points (Normal) in all five situations of the table, and it can be seen that this was better than other companies that had condition changes permitted (i.e., “Slightly improved” to “Worsened” companies).

The Financing Facilitation Act seemed to directly affect the attitudes of financial institutions. Looking at “Financial institution’s attitude toward loaning” in

Table 5, the average state of companies with “Improved” business performance surpassed a score of 3 at 3.55, but “Slightly improved” companies were below 3 at 2.78, and “Slightly worsened” and “Worsened” companies were low at around 2. On the other hand, the state of companies that did not apply for changes of loan conditions, as they did not feel them necessary (Changes-unneeded companies), was shown as a score of 3.59, which was far higher than that of firms that requested loan condition changes. Only “Improved” firms could obtain a similar score to Changes-unneeded companies. Financial institutions had a strict attitude towards companies that had changes in conditions permitted, although they seemed to lightly allow the requests of payment condition changes.

Also, “Slightly worsened” and “Worsened” companies answered scores of 1.88 and 1.41 regarding their finances, which were very much below 2, showing that they had very severe financial situations. On the other hand, one can see that “Improved” companies had a better situation (3.62) even than Changes-unneeded companies (3.24). Notably, regarding the “attitude toward loaning” factor, the “Improved” company’s score was mostly the same with Changes-unneeded companies. It suggested that “Improved” companies had good relations with the financial institutions. This was consistent with the argument that companies who were supported financially by the institutions could have improved their performance.

5.3.3. Changes in the Debt Balance from Financial Institutions

Table 6 shows the changes in the balance of debt from financial institutions since the Financing Facilitation Act was enforced. For “Improved” companies the percentage that answered “Reduced” was very high at 74.8%. And even for “Slightly improved” companies the high “Reduced” rate of 68.5% stood out. In contrast, “Worsened” companies had a low rate of 48.8%.

Considering the fact that in

Table 5 there was a trend of “Improved” companies answering that their financing was “Good”, they reduced their borrowing and progressed in restructuring their debts while having no problems with finances.

5.3.4. The Details of Payment Condition Changes

In this study, the details of the first changes in payment conditions permitted were inquired about. The results of this are shown in

Table 7. One can see that condition changes such as postponements of the repayment period and payment extensions, which are less harmful to financial institutions, made up the greater part for every business performance category.

Interestingly, changes that involved more merits to firms, such as interest rate reduction, exemption, and principal debt reduction, had no clear difference in the subsequent performance. For example, 12.9% of “Improved” firms received “Interest rate reduction and exemption”, while 15.5% of “Slightly worsened” and 9.9% of “Worsened” received it.

The following point should be kept in mind. There were many cases where revitalization was not completed after the initial condition changes, and additional changes were carried out afterward. These subsequent changes may also be of different types than the initial, which were not inquired about in this study.

5.4. Relations with Main Banks

In this study, the names, institution types, years of business, and debt balance were inquired about from financial institutions who lent the most money to a company (usually referred to below as a company’s “main bank”) at the end of their latest accounting period.

Table 8 shows the distribution of financial institution types of these main banks, separated by companies that did and did not receive condition changes.

In the Changes-permitted companies column, one can see the main bank types of companies that received condition changes and find that regional banks were the majority, followed by Shinkin banks, and major banks

9. One can see that, when compared with the distribution of main bank types of Changes-unneeded companies, relatively more Changes-permitted companies had Shinkin banks as their main banks. In other words, Shinkin banks more actively worked to support companies through easing repayment conditions than other bank categories.

Table 9 shows the state of improvement of the company’s business performance by the types of main banks. Less than 10% of firms that had major banks as their main banks answered “Improved”, while 20% of those that had other bank types as main banks answered “Improved”. Accordingly, loan condition changes by major banks were not as effective in improving firms’ performance as those by other banks. It is said that major banks do not give support to underperforming small and medium enterprises to help revitalize them, and these results back this argument up. Also, for credit unions, though we must note that there were not many corresponding companies, “Slightly worsened” and “Worsened” had high percentages. It is known that credit unions empathetically support small and medium enterprises, but the fact that there was a high percentage of

worsened trend companies may be because many credit unions lacked the capacity to support these companies effectively.

When calculating supporting performances of each main bank type, where “Improved” was 5 points, “Slightly improved” was 4 points, “Didn’t change” was 3, “Slightly worsened” was 2, and “Worsened” was 1, it was governmental financial institutions that had the highest score at 3.77, while regional banks (3.58), second regional banks (3.57), and Shinkin banks (3.53) were mainly on the same level, and major banks (3.34) and credit unions (3.36) were the lowest.

5.5. The Changes in Attitude of Financial Institutions after Condition Changes

In this study, the change in the attitude of financial institutions after initial changes in loan conditions were permitted was inquired about. The results of this question are shown in

Table 10.

Over 70% of “Improved” companies answered “Supported us empathetically”, though the rates of the

worsened trend companies choosing it were between 40% and 50%

10. Conversely, for the answer “Did not accept new loans of funds”,

worsened trend companies surpassed 30%, while “Improved” companies were under 20%. Apparently, empathetical support from financial institutions was very effective in the revitalization of companies. From this perspective, the fact that only 60% of Changes-permitted companies selected “Supported us empathetically” suggested further efforts by financial institutions to provide their support to firms were necessary.

While it was natural that “Requested the formation and carrying out of a strict business improvement plan” was answered by a great many “Worsened” companies, it was notable that even more than 20% of “Improved” companies chose it. This suggested that financial institutions did not necessarily adopt an overly generous attitude with “Improved” companies.

Furthermore, we investigated what other options were selected by the companies that selected this 3rd option, and the result of that is in

Table 11.

The “Relevant companies” denotes the number of firms that selected “Requested the formation and carrying out of a strict business improvement plan”. For example, 58 of 256 “Improved” firms selected this option. Here, for simplicity, we referred to the firms that selected this option as “BIP firms”. According to

Table 11, 55.2% of the BIP firms selected “Supported us empathetically”. Conversely, among “Slightly worsened” and “Worsened” BIP firms, only around 20% chose “Supported us empathetically”. In the case where banks showed a “strict” but “empathetical” attitude, companies were likely to improve their performance, but if banks showed just a “strict” attitude, companies were likely to fail to improve their performance.

5.6. Self-Evaluation on the Reasons for the Improvement

For companies that answered “Improved” and “Slightly improved”, the reason for their improvement was asked, and these results are shown in

Table 12. In this question, options for the reasons for the improvement were categorized into three areas: (A) the company’s efforts, (B) the relationship with the financial institution, and (C) the relationship with customers, each having eight, three, and five options, respectively.

Over 40% of companies chose the options “A1. Costs were cut”, “A5. Management and staff sensed a crisis”, and “C3. New customers were gained”. Thus, these good-performing companies cut costs, revitalized the company’s organization, and increased sales.

Table 12 also separates “Improved” and “Slightly improved” companies. Of course, “Improved” and “Slightly improved” were subjective factors in this study, but because in this paper we found visible differences between “Improved” and “Slightly improved” companies in several questions, it might be useful to separate them here too.

Excluding “A3. Personnel expenses were cut through restructuring”, “Improved” companies chose all of the options more often than “Slightly improved” companies. The largest difference between the two types of companies was found in “A6. The business improvement plan took a better direction”, followed by “C2. Sales of existing products/services increased”, “C4. Transactions with existing customers expanded”, “C3. New customers were gained”, “A8. Regular work was continued without worrying about finances”, and “B1. Forward-looking funds were procured from the financial institution”. It was natural that there were a lot of C options selected, which contributed to the company’s core business.

Furthermore, we should also take note of the high rates of A8 and B1, which were connected to finances. As firms that received payment condition changes were less creditworthy, it was understandable for financial institutions to hesitate to procure forward-looking funds (e.g., new loan for equipment). However, consulting-related items such as B2 and B3 just reached 30%, and this fact helped to point out an area that needed improvement. While private financial institutions have worked on increasing the ability of financing based on an evaluation of business feasibility, not on collateral or guarantee, their consultation ability still needed to be grown much more.

5.7. Self-Evaluation on the Reasons for Worsening

In this study, for companies that selected “Worsened” or “Slightly worsened”, the chief reasons for the worsening were asked. These results are organized by company employee numbers, as shown in

Table 13, because the differences among different sizes of firms were interesting.

The largest difference between the smallest-sized companies (1 to 9 people) and the biggest-sized companies (70 people and over) was found in “B3. Relations with the financial institution became estranged”, followed by “A8. Finances were worried about and regular work couldn’t get done”, “B2. Information helpful to the business wasn’t received from the financial institution”, “C4. Transactions with existing customers decreased”, and “B1. Forward-looking funds couldn’t be procured from the financial institution”. Remarkably, aside from C4, they were all related to finances. Thus, one can see that there was a strong tendency that financial problems in the smallest-sized companies were seen (at least subjectively) as the major causes of their worsened performance.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Economic theory can predict that the Financing Facilitation Act will bring moral, hazardous problems. Actually, previous studies often pointed out negative effects of the Financing Facilitation Act, such as moral hazards of banks and borrowers as well as opaque bank disclosures. However, the act surely mitigated the negative impacts of the crisis on SMEs. It seems useful to investigate whether we can manage its negative effects and enjoy its benefits. Therefore, this paper investigated what type of factors caused SMEs to improve or worsen their business performance after receiving repayment condition changes. For this purpose, we used the “Financial Field Study after the End of the Financing Facilitation Act” carried out by the RIETI in Oct 2014. The following is a conclusion of the chief results.

Of the companies that received changes in their payment conditions, around 60% had improved business performance afterward; therefore, loan condition changes successfully helped many companies improve their performance. However, among Changes-permitted companies, there was a non-negligible number of companies that could not improve their performance. Therefore, while we can say that so-called zombie companies were not often rescued by easing loan conditions, we need to strengthen the ability of financial institutions to support underperforming firms.

Compared with Changes-unneeded companies, there were many Changes-permitted companies that responded that the loaning attitude of financial institutions was strict. However, as companies that experienced good loaning attitudes from financial institutions tended to respond that their performance became “Improved”, the attitude of financial institutions is an important factor in performance improvement.

When we look at the changes in performance by the type of a company’s main bank, companies that do business with governmental financial institutions have less worsened trends, and conversely, companies that do business with major banks and credit unions had fewer replies of “Improved”. It is often pointed out that major banks tend to avoid troublesome support to those with condition changes, and these results back this argument up. On the other hand, in spite that credit unions work at giving such support (despite being troublesome), their “Improved” rate was very low. This result shows that they are lacking in expertise to revitalize businesses.

On inquiring about the changes in the attitude of financial institutions after condition changes were permitted, more than 70% of “Improved” companies chose “Supported us empathetically”, while only about 45% of “Worsened” or “Slightly worsened” companies chose it. In contrast, over 30% of worsened trend companies replied “Did not accept new loans of funds”, while less than 20% of “Improved” companies did so. Even if condition changes were received in a similar fashion, the attitude of the financial institution afterward made a big difference. The result also confirms that current support from financial institutions towards worsened companies has been insufficient.

On the enforcement of the Financing Facilitation Act, which requires financial institutions to actively agree to change repayment conditions as much as possible, it was strongly criticized that the simple propping up of underperforming companies (so-called “zombie companies”) was nothing more than delaying the problem. Actually, because of this theoretical conjecture, many previous studies criticized the act. However, there may be a positive side, because it mitigated the credit crunches of SMEs. This paper can use the above-mentioned survey data and provide empirical evidence on this matter. This paper found that the ratio of zombie companies overall was small, if any. More important, unless appropriate support for improving business is not provided by financial institutions after changing loan conditions, the chances of improvement is low. In other words, not having appropriate support from financial institutions is what turned underperforming but high-potential companies into zombie companies.

In sum, although the Financing Facilitation Act inevitably involves negative side effects, as argued by many researchers, we consider whether negative effects may be mitigated by banks’ behaviors. Our results suggest that the act is not bad in itself, and if it is used properly, it can produce good results. To make banks use it properly, it is necessary for the banking authority to monitor banks’ behaviors closely. All in all, in times of crisis, there is a need to adopt a policy like the Financing Facilitation Act, but in that case the banking authority should do its best to minimize negative effects of the policy measure. Also, continuing such strict banking supervision in normal times is not desirable, as it restricts the behavior of banks. Needless to say, the measure should be abolished as soon as possible, if the situation becomes normal.

Lastly, we point out the limitations of this paper. First, in this paper, we only demonstrated the simple relationship between responses. We need to explore causality and multilateral relations. Second, companies that had gone bankrupt after receiving condition changes were not able to be analyzed in this study. This means that companies in this study who replied “Worsened” were actually those that were able to avoid bankruptcy, and it can be regarded that the degree referred to as “Worsened” is not so serious. The negative side of the repayment condition changes may be underestimated. For this, analysis with datasets including information about bankrupt firms will be necessary.