Asymmetric Effects of Policy Uncertainty on the Demand for Money in the United States †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Money Demand Models and Methods

3. The Results

4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Data Definition and Sources

- (a)

- International Financial Statistics (IFS) of International Monetary Fund (IMF).

- (b)

- Economic Policy Uncertainty Group: http://www.policyuncertainty.com/us_monthly.html

- (c)

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED)

Appendix A.2. Variables

References

- Aftab, Muhammad, Karim Bux Shah Syed, and Naveed Akhter Katper. 2017. Exchange-rate volatility and Malaysian-Thai bilateral industry trade flows. Journal of Economic Studies 44: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahking, Francis. 2002. Model Mis-Specification and Johansen’s Co-Integration Analysis: An Application to the U.S.A. Money Demand. Journal of Macroeconomics 24: 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shayeb, Abdulrahman, and Abdulnasser Hatemi-J. 2016. Trade openness and economic development in the UAE: An asymmetric approach. Journal of Economic Studies 43: 587–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, Sebastian, and M. Ishaq Nadiri. 1981. Demand for Money in Open economies. Journal of Monetary Economics 7: 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arize, Augustine C., John Malindretos, and Emmanuel U. Igwe. 2017. Do Exchange Rate Changes Improve the Trade Balance: An Asymmetric Nonlinear Cointegration Approach. International Review of Economics and Finance 49: 313–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, and Seyed Hesam Ghodsi. 2017. Policy Uncertainty and House Prices in the United States of America. Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management 23: 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, and Majid Maki-Nayeri. 2018a. Policy Uncertainty and the Demand for Money in Korea: An Asymmetry Analysis. International Economic Journal 63: 567–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, and Majid Maki-Nayeri. 2018b. Policy Uncertainty and the Demand for Money in Australia: An Asymmetry Analysis. Australian Economic Papers. forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, and Mohammad Pourheydarian. 1990. Exchange Rate Sensitivity of the Demand for Money and Effectiveness of Fiscal and Monetary Policies. Applied Economics 22: 1377–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, Sahar Bahmani, Alice Kones, and Ali M. Kutan. 2015. Policy Uncertainty and the Demand for Money in the United Kingdom. Applied Economics 47: 1151–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, Alice Kones, and Ali Kutan. 2016. Policy Uncertainty and the Demand for Money in the United States. Applied Economics Quarterly 62: 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, Hanafiah Harvey, and Farhang Niroomand. 2018. On the Impact of Policy Uncertainty on Oil Prices: An Asymmetry Analysis. International Journal of Financial Studies 6: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Scott R., Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis. 2016. Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty. Quarterly Journal of Economics 131: 1593–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Lawrence. 2012. Short Run Money Demand. Journal of Monetary Economics 59: 622–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogaard, Jonathan, and Andrew Detzel. 2015. The Asset-Pricing Implications of Government Economic Policy Uncertainty. Management Science 61: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Woon Gyu, and Seonghwan Oh. 2003. A Demand Function with Output Uncertainty, Monetary Uncertainty, and Financial Innovations. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 35: 685–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Benjamin M. 1984. Lessons from the 1979–1982 Monetary Policy Experiment. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 74: 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Gogas, Periklis, and Ioannis Pragidis. 2015. Are there asymmetries in fiscal policy shocks? Journal of Economic Studies 42: 303–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoriou, Andros. 2017. Modelling non-linear behaviour of block price deviations when trades are executed outside the bid-ask quotes. Journal of Economic Studies 44: 206–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Rangan, and Anandamayee Majumdar. 2014. Reconsidering the Welfare Cost of Inflation in the U.S.A.: A Nonparametric Estimation of the Nonlinear Long-Run Money-Demand Equation Using Projection Pursuit Regressions. Empirical Economics 46: 1221–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafer, Rik W., and Dennis W. Jansen. 1991. The Demand for Money in the United States: Evidence from Cointegration Tests. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 23: 155–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Dennis, and Robert H. Rasche. 1991. Long-Run Income and Interest Elasticities of Money Demand in the United States. The Review of Economics and Statistics 73: 665–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawadi, Fredj, and Ricardo M. Sousa. 2013. Money in the Euro Area, the US and the UK: Assessing the Role of Nonlinearity. Economic Modelling 32: 507–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Wensheng, and Ronald A. Ratti. 2013. Oil Shocks, Policy Uncertainty and Stock Market Return. International Financial Markets, Institutions, and Money 26: 305–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Jun-Hyung, and Chang-Min Lee. 2015. International Economic Policy Uncertainty and Stock Prices: Wavelet Approach. Economics Letters 134: 118–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, Luiz, Claudio Foffano Vasconcelos, Jose Simão, and Helder Ferreira de Mendonça. 2016. The quantitative easing effect on the stock market of the USA, the UK and Japan: An ARDL approach for the crisis period. Journal of Economic Studies 43: 1006–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNown, Robert, and Myles S. Wallace. 1992. Cointegration Tests of a Long-Run Relationship between Money Demand and the Effective Exchange Rate. Journal of International Money and Finance 11: 107–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundell, Robert A. 1963. Capital Mobility and Stabilization Policy Under Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rates. Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science 29: 475–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusair, Salah A. 2017. The J-curve Phenomenon in European Transition Economies: A Nonliear ARDL Approach. International Review of Applied Economics 31: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, Ľuboš, and Pietro Veronesi. 2013. Policy Uncertainty and Risk Premia. Journal of Financial Economics 110: 520–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. Hashem, Yongcheol Shin, and Richard J. Smith. 2001. Bounds Testing Approaches to the Analysis of Level Relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics 16: 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B. Bhaskara, and Saten Kumar. 2011. Is the U.S.A. Demand for Money Unstable? Applied Financial Economics 21: 1263–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, Afsin. 2013. Estimating Money Demand Function under Uncertainty by Smooth Transition Regression Model. Paper presented at the 6th Annual International Conference on Mediterranean Studies, Athens, Greece, March 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, Afsin. 2018. Staying Vigilant of Uncertainty to Velocity of Money: An Application for Oil-Producing Countries. OPEC Energy Review 42: 170–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Yongcheol, Byungchul Yu, and Matthew Greenwood-Nimmo. 2014. Modelling Asymmetric Cointegration and Dynamic Multipliers in a Nonlinear ARDL Framework. In Festschrift in Honor of Peter Schmidt: Econometric Methods and Applications. Edited by Robin C. Sickles and William C. Horrace. New York: Springer, pp. 281–314. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yiming. 2011. The Stability of Long-Run Money Demand in the United States: A New Approach. Economics Letters 111: 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yizhong, Carl R. Chen, and Ying Sophie Huang. 2014. Economic Policy Uncertainty and Corporate Investment: Evidence from China. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 26: 227–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | For more information and source of the data visit Economic Uncertainty Policy Group: http://www.policyuncertainty.com/europe_monthly.html. |

| 2 | Other measures of uncertainty have been used by others. For example, Sahin (2013) assessed the impact of inflation uncertainty on the demand for money in Turkey and found that increased uncertainty increased precautionary motives. Sahin (2018) looked at the impact of impact of the U.S.A. money supply volatility as a measure of uncertainty on the velocity of the money in Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) countries and finds significant long-run effects only in three countries. |

| 3 | For more, see Mundell (1963); Arango and Nadiri (1981); and Bahmani-Oskooee and Pourheydarian (1990). |

| 4 | Other studies that have estimated the demand for money in the U.S.A. without uncertainty measure are: Hafer and Jansen (1991); Hoffman and Rasche (1991); McNown and Wallace (1992); Ahking (2002); Wang (2011); Rao and Kumar (2011); Ball (2012); Jawadi and Sousa (2013); and Gupta and Majumdar (2014). |

| 5 | Another advantage of this approach is that by including short-run dynamic adjustment process in estimating the long-run elasticities, the approach accounts for feedback effects among all variables (Pesaran et al. 2001, p. 299). |

| 6 | See Shin et al. (2014, p. 219). This proposition is based on dependency between the two partial sum variables. |

| 7 | For some other application of these methods in recent literature, see Gogas and Pragidis (2015); Al-Shayeb and Hatemi-J (2016); Lima et al. (2016); Nusair (2017); Aftab et al. (2017); Arize et al. (2017); and Gregoriou (2017). Furthermore, we have used statistical package Microfit 5.5 by Pesaran and Pesaran downloadable for free at: http://www.econ.cam.ac.uk/people-files/emeritus/mhp1/Microfit/Microfit.html. |

| 8 | The ECMt−1 test is an alternative test under which normalized long-run estimates and Equation (1) are used to generate the error term denoted by ECM as follows:

We then move back to an error-correction model (2) and replace the linear combination of lagged level variables by ECMt−1 and estimate the new specification at the same optimum lags. A significantly negative coefficient obtained for ECMt−1 implies that variables are adjusting toward their long-run equilibrium values or cointegrating. The value of the estimated coefficient measures the speed of adjustment. Since the t-test is used to judge significance of the coefficient attached to ECMt−1, the test is also known as the t-test for cointegration. Like the F test, Pesaran et al. (2001, p. 303) provided new critical values for this test too. Note also that the value. |

| 9 | These finding for the U.S.A. are similar to those of Bahmani-Oskooee and Maki-Nayeri (2018a, 2018b) for Korea and Australia respectively. |

| Variables | |||||||

| M | Y | r | Ln(Pt/Pt−1) | EX | PU | ||

| Mean | 3273.31 | 12402.14 | 3.33 | 0.53 | 115.55 | 110.44 | |

| Min | 2244.30 | 7537.93 | 0.01 | −0.20 | 92.51 | 52.09 | |

| Max | 5578.80 | 17272.47 | 8.54 | 1.20 | 170.40 | 235.08 | |

| Std Dev | 976.73 | 2899.15 | 2.57 | 0.24 | 14.01 | 34.20 | |

| Skewness | 0.90 | −0.11 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.86 | |

| Kurtosis | 2.62 | 1.65 | 1.72 | 3.52 | 4.74 | 3.59 | |

| ADF Test Results (Augmented Dickey-Fuller test) | |||||||

| Variables | |||||||

| Ln M | Ln Y | Ln r | Ln(Pt/Pt−1) | Ln EX | Ln PU | ||

| With Constant | Level | −2.10(1) | −1.88(1) | −1.53(1) | −3.04(2) * | −2.88(2) | −5.22(0) ** |

| First Difference | −8.06(0) ** | −4.88(1) ** | −9.04(0) ** | −12.33(1) ** | −7.97(1) ** | −12.22(1) ** | |

| With Constant and Trend | Level | −0.61(0) | −1.34(2) | −1.89(1) | −6.26(0) ** | −2.99(1) | −5.54(0) ** |

| First Difference | −8.65(0) ** | −7.78(0) ** | −9.03(0) ** | −12.28(1) ** | −8.12(1) ** | −12.17(1) ** | |

| Panel A: Short-Run Coefficient Estimates | |||||||||||||

| Lag Order | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| ∆LnM | - | ||||||||||||

| ∆LnY | −0.32 a | ||||||||||||

| (−2.08) * | |||||||||||||

| ∆Ln r | −0.01 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.004 | −0.01 | 0.004 | −0.004 | −0.003 | 0.01 | ||||

| (−2.02) * | (−0.94) | (0.52) | (1.34) | (−2.24) * | (1.57) | (−1.32) | (−0.60) | (1.97) | |||||

| ∆Ln(Pt/Pt−1) | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| (−4.54) ** | (1.33) | (2.67) ** | |||||||||||

| ∆LnLEX | 0.11 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.003 | −0.08 | 0.05 | |||||||

| (2.93) ** | (−1.24) | (2.11) * | (0.09) | (−2.81) ** | (2.80) ** | ||||||||

| ∆LnPU | 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| (3.98) ** | |||||||||||||

| Panel B: Long-Run Coefficient Estimates | |||||||||||||

| Constant | LnY | Ln r | Ln(Pt/Pt−1) | LnEX | LnPU | ||||||||

| 131.45 | −14.06 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.69 | −0.87 | ||||||||

| (0.77) | (−0.74) | (0.65) | (0.79) | (0.89) | (−0.64) | ||||||||

| Panel C: Diagnostics | |||||||||||||

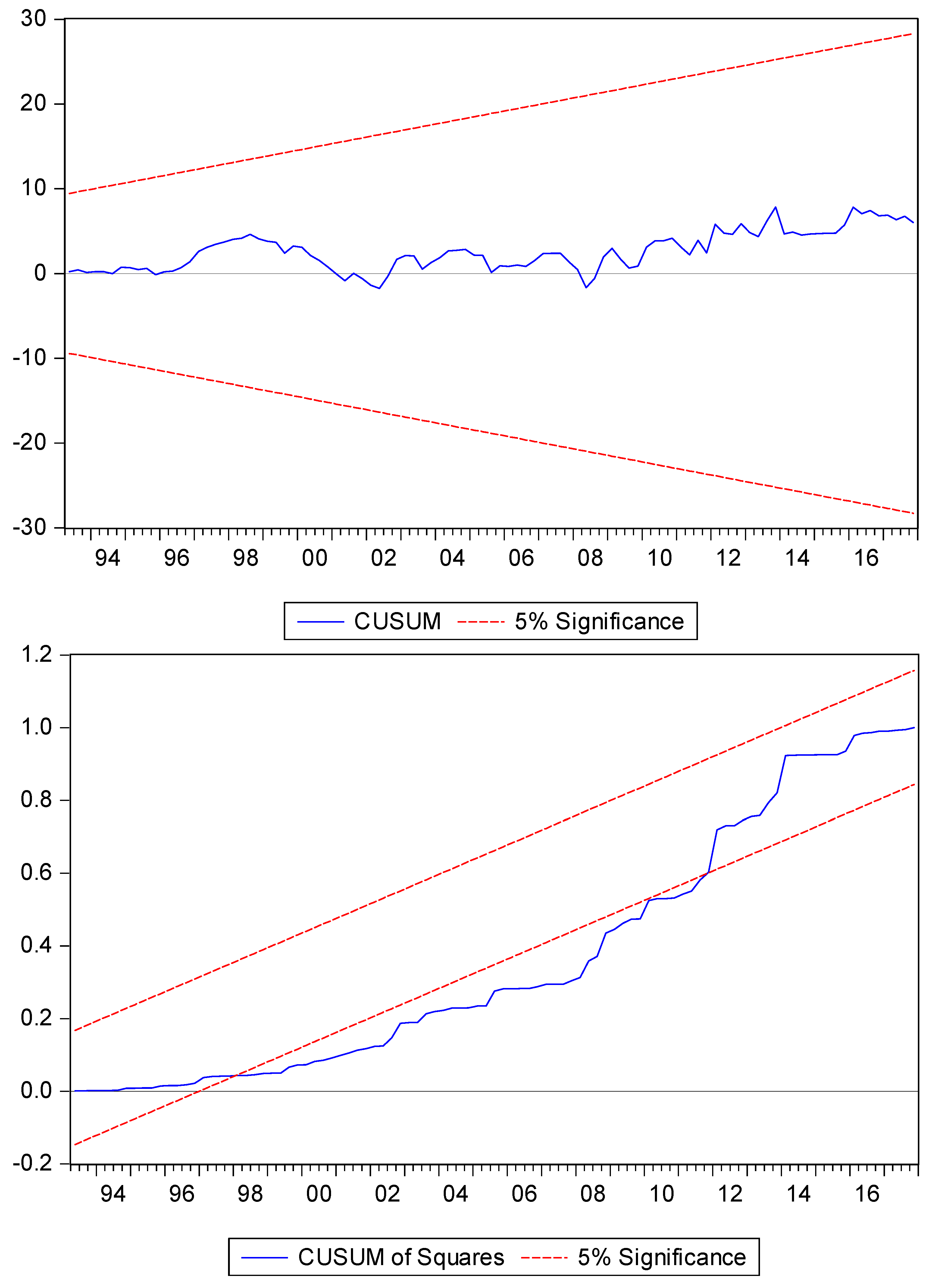

| F b | ECMt−1 | LM d | RESET e | CUSUM (CUSUMQ) | |||||||||

| 3.46 * | 0.01 c | 0.32 | 23.32 ** | 0.55 | S (UNS) | ||||||||

| (0.64) | |||||||||||||

| Panel A: Short-Run Coefficient Estimates | |||||||||||||

| Lag Order | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| ∆LnM | - | −0.20 a | −0.23 | −0.09 | 0.02 | −0.19 | |||||||

| (−2.93) ** | (−4.03) ** | (−1.34) | (0.38) | (−2.26) * | |||||||||

| ∆LnY | −0.39 | ||||||||||||

| (2.53) ** | |||||||||||||

| ∆Ln r | −0.01 | −0.002 | 0.003 | 0.01 | −0.003 | 0.004 | −0.005 | −0.004 | 0.01 | ||||

| (−5.56) ** | (−1.13) | (1.31) | (2.31) ** | (−1.34) | (2.62) ** | (−2.34) ** | (−1.01) | (5.23) ** | |||||

| ∆Ln(Pt/Pt−1) | −0.02 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.01 | −0.003 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | ||||

| (−5.04) ** | (0.40) | (0.84) | (1.26) | (−0.65) | (−1.51) | (−1.29) | (3.24) ** | (−4.49) ** | |||||

| ∆LnLEX | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.10 | |||

| (3.37) ** | (−0.63) | (1.70) | (−0.31) | (−2.88) ** | (0.78) | (−0.24) | (−0.52) | (2.05) * | (−4.24) ** | ||||

| ∆POS | 0.002 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| (0.32) | (−1.94) * | (1.22) | (2.35) ** | (1.10) | (3.17) ** | (−2.27) * | (1.45) | (2.48) ** | (2.35) ** | (2.37) ** | |||

| ∆NEG | 0.02 | ||||||||||||

| (2.60) ** | |||||||||||||

| Panel B: long-run coefficient estimates | |||||||||||||

| Constant | LnY | Ln r | Ln(Pt/Pt−1) | LnEX | POS | NEG | |||||||

| −4.29 | 0.49 | −0.28 | 0.13 | 1.52 | −0.78 | 0.22 | |||||||

| (−0.46) | (0.52) | (−3.31) ** | (5.10) ** | (5.33) ** | (−3.81) ** | (1.58) | |||||||

| Panel C: Diagnostics | |||||||||||||

| F b | ECMt−1 c | LM d | RESET e | CUSUM (CUSUMQ) | Wald-L f | Wald-S | |||||||

| 6.08 ** | −0.07 | 0.29 | 2.57 | 0.67 | S (UNS) | 9.01 ** | 58.30 ** | ||||||

| (−2.95) | |||||||||||||

| Panel A: Short-Run Estimates | |||||||||||||

| Lag Order | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| ∆LnM | - | ||||||||||||

| ∆LnY | −0.17 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.32 | −0.86 | 0.46 | 0.15 | −0.15 | 0.28 | −0.50 | 0.19 | ||

| (−1.16) a | (0.66) | (0.47) | (1.69) | (−4.99) ** | (3.20) ** | (1.06) | (−0.97) | (2.12) * | (−4.10) ** | (1.97) | |||

| ∆Ln r | −0.01 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.01 | −0.005 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.01 | ||||

| (−5.34) ** | (2.71) ** | (0.33) | (2.29) * | (−2.02) * | (0.56) | (−0.62) | (−0.88) * | (3.62) ** | |||||

| ∆Ln(Pt/Pt−1) | −0.02 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.0004 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | ||||

| (−3.96) ** | (0.88) | (1.15) | (2.46) ** | (−2.58) ** | (0.10) | (−3.44) ** | (4.03) ** | (−4.42) ** | |||||

| ∆LnLEX | 0.10 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.14 | 0.07 | ||

| (4.06) ** | (−1.13) | (0.35) | (0.36) | (−3.28) ** | (1.43) | (0.45) | (−2.17) * | (2.80) ** | (−5.15) ** | (3.38) ** | |||

| ∆POS | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.004 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | |||

| (3.09) ** | (−2.31) ** | (2.59) ** | (2.47) ** | (1.71) | (1.23) | (−0.79) | (−1.21) | (6.24) ** | (2.20) * | ||||

| ∆NEG | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0001 | −0.003 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.02 | −0.02 | ||||

| (1.67) * | (1.96) * | (0.74) | (0.01) | (−0.54) | (0.99) | (0.65) | (3.61) ** | (−5.62) ** | |||||

| Panel B: long-run coefficient estimates | |||||||||||||

| Constant | LnY | Ln r | Ln(Pt/Pt−1) | LnEX | POS | NEG | |||||||

| 1.81 | 0.12 | −0.18 | 0.09 | 0.95 | −0.50 | −0.08 | |||||||

| (0.26) | (0.15) | (−3.41) ** | (3.33) ** | (6.73) ** | (−4.03) ** | (−0.53) | |||||||

| Panel C: Diagnostics | |||||||||||||

| F b | ECMt−1 c | LM d | RESET e | CUSUM (CUSUMQ) | Wald-L f | Wald-S | |||||||

| 3.77 * | −0.09 | 0.03 | 2.36 | 0.68 | S (S) | 3.71 * | 31.62 ** | ||||||

| (−3.08) | |||||||||||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bahmani-Oskooee, M.; Maki-Nayeri, M. Asymmetric Effects of Policy Uncertainty on the Demand for Money in the United States. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2019, 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12010001

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Maki-Nayeri M. Asymmetric Effects of Policy Uncertainty on the Demand for Money in the United States. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2019; 12(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleBahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, and Majid Maki-Nayeri. 2019. "Asymmetric Effects of Policy Uncertainty on the Demand for Money in the United States" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12010001

APA StyleBahmani-Oskooee, M., & Maki-Nayeri, M. (2019). Asymmetric Effects of Policy Uncertainty on the Demand for Money in the United States. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12010001