Abstract

Background/Objectives: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides (LPP) represents a rare variant of Oral Lichen Planus in which the typical pemphigoid-associated antibodies, BP180 and BP230, are present. The objectives of this Systematic Review are to analyze the data currently available in the literature on this rare condition, with the aim of laying the groundwork for future investigations and research. Methods: This Systematic Review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the registration number CRD420251133018. Subsequently, a search was conducted on PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Ovid using specific keywords combined with Boolean operators. Articles published up to 2025 were included. The following types of studies were considered eligible: case reports, clinical conferences, clinical studies, clinical trials, controlled clinical trials, letters, multicenter studies, observational studies, randomized controlled trials, and human-based studies. Book chapters, systematic reviews, narrative reviews, in vitro studies, and animal models were excluded. Results: A total of 67 articles were initially identified; following thorough review and exclusion, 20 articles were retained. The patient data extracted from these selected studies were used to construct a table in which patients were categorized according to both qualitative and quantitative variables. The results highlight that LPP is a condition requiring a complex diagnostic process involving both histological examination and serological testing (Immunofluorescence and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay—ELISA). Conclusions: Furthermore, with the advent of immunotherapy, an increasingly well-documented new category of drug-induced LPP has emerged, associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors.

1. Introduction

Lichen Planus Pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare variant of Lichen Planus (LP), characterized by the coexistence of clinical and pathological features consistent with Oral Lichen Planus (OLP), together with the presence of autoantibodies against BP180 and BP230, which are typically associated with pemphigoid diseases [1]. The association between OLP and Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid (MMP) was first described by Kaposi in 1892. Subsequently, this condition has been reported in association with neoplasms, viral diseases, phototherapy, and certain types of medications [2]. The prevalence of LPP is approximately 1 case per 1,000,000 patients; however, reported cases are very limited and often underdiagnosed [3]. The sex ratio is skewed toward women, who are more frequently affected [4]. The age of onset is variable, ranging from the third to the sixth decade of life [1]. Clinically, LPP manifests with pruritic erythematous skin lesions accompanied by bullous eruptions. Oral involvement is not always observed; however, when present, it is characterized by erosive and ulcerative lesions developing on pre-existing OLP.

From a clinical, histopathological, and immunoserological standpoint, the diagnosis of LPP may be challenging, as it overlaps with other conditions such as Bullous OLP, Bullous Pemphigoid (BP), and Paraneoplastic Pemphigus (PNP) [1,5,6]. PNP is a rare complication in which an underlying neoplasm triggers immune dysregulation that drives the disease manifestations [6]. Clinically, it differs from related conditions because the lesions are very severe, extensive, and refractory to therapy [6]. It usually regresses following treatment of the underlying neoplasm [6]. Bullous OLP is characterized by the development of bullous lesions on pre-existing lichenoid lesions, whereas in LPP, vesicles typically arise outside the areas of LP involvement (although cases of LPP with vesicle formation on lichenoid lesions have also been reported in the literature) [1]. The vesicles in BP tend to evolve into erosive–ulcerative lesions with a longer and more severe course than those observed in LPP [1]. BP typically affects older patients compared to LPP. LPP lesions more frequently involve the flexural surfaces of the limbs, whereas BP lesions are more generalized [1]. It is believed that LPP arises from the lichenoid inflammation itself, which may promote the development of an autoimmune response against basement membrane proteins through an epitope spreading mechanism—a process also described in the association between OLP and PNP [1,7]. In fact, chronic tissue damage leads to the release of multiple autoantigens, thereby sustaining the immune response against them [2,7,8]. The disruption of the Basement Membrane Zone (BMZ) due to mast cell degranulation may represent the triggering factor for epitope spreading [2,8]. Several cases of drug-induced LPP have been reported in the literature, associated with agents such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitors and its ligand (PD-L1) inhibitors including pembrolizumab and nivolumab, as well as drugs such as gabapentin and risankizumab [9,10,11]. The treatment of LPP is largely experience-based and typically begins with corticosteroids, high-potency topical agents for limited disease, and systemic corticosteroids for more extensive or rapidly progressive involvement [1,8,12]. Steroid-sparing options commonly used include dapsone and acitretin [1]. In refractory cases, calcineurin-inhibiting or other immunosuppressive therapies such as cyclosporine or mycophenolate may be considered, and low-dose methotrexate is occasionally employed [1]. More recently, advanced therapies including dupilumab, intravenous immunoglobulin, and rituximab have been reported to induce remission in difficult or drug-induced presentations [12,13,14]. Because LPP is rare and heterogeneous, management should be individualized, with careful evaluation and withdrawal of potential trigger medications when feasible and close monitoring for relapse [1].

The aim of this systematic review is to analyze the documented cases of LPP reported in the literature, in order to shed light on a condition that remains poorly studied and understood, and to provide a basis for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

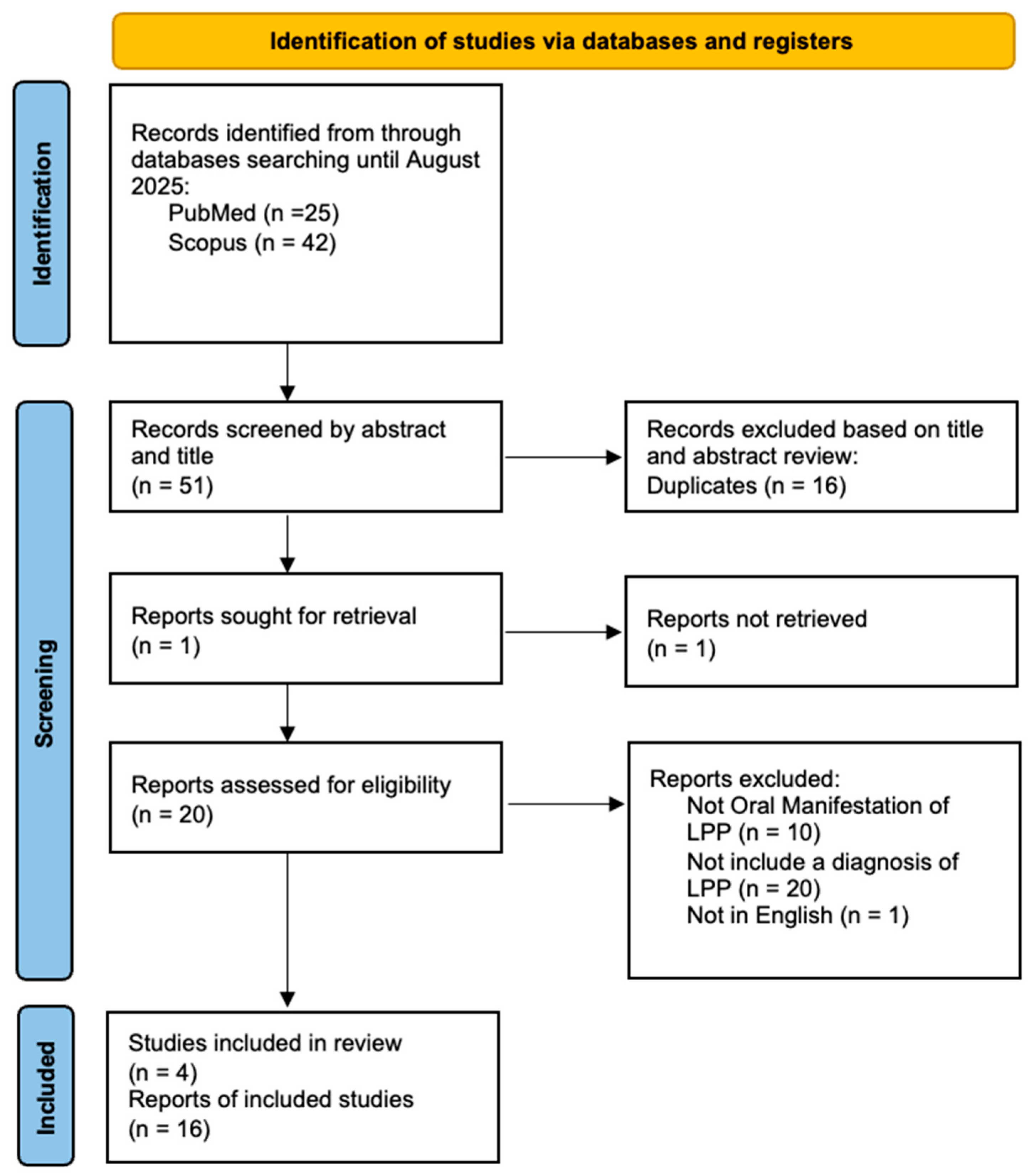

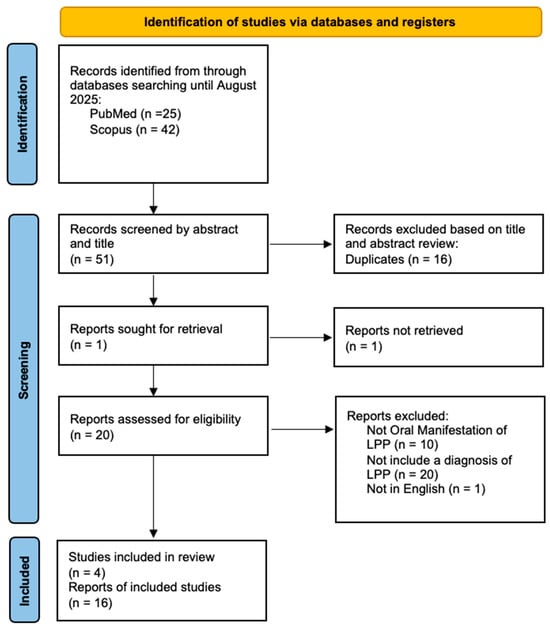

This study was registered on 26 August 2025, in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Review (PROSPERO) under the registration number CRD420251133018. This Systematic Review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Table S1).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

For this Systematic Review, we included case reports, clinical conferences, clinical studies, clinical trials, controlled clinical trials, letters, multicenter studies, observational studies, randomized controlled trials, and human-based studies, while excluding book chapters, systematic reviews, reviews, in vitro studies, and animal models. Furthermore, only studies published in English were considered. The study population included patients with oral manifestations of LPP according with the authors of each article selected.

P (Population): Patients with oral manifestations of LPP, as defined by the authors of the included studies.

I (Intervention): Clinical–histological features compatible with OLP plus immuno-serological evidence of a pemphigoid disorder (autoantibodies to BP180/NC16A and/or BP230 assessed by DIF, IIF, and/or ELISA). Recording of potential drug triggers and treatments administered.

C (Comparison): Not Required.

O (Outcomes): Oral disease features (type, extent, and localization of lesions), involvement of skin and/or other mucous membranes, presence of underlying conditions or pharmacological triggers, serological confirmation (DIF/IIF/ELISA; BP180/NC16A, BP230), Patient outcomes (complete or near-complete remission, persistent disease, relapse).

S (Study design).

- Included: case reports, case series, observational studies, clinical trials, clinical conferences, letters, and other human-based studies.

- Excluded: book chapters, systematic/narrative reviews, in vitro studies, and animal models.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

The literature research covered articles published in English between 1990 and August 2025. The research was performed using MEDLINE/Pubmed, Ovid and Scopus, applying search filters, such as (“oral lichen planus” OR “lichen planus” OR “OLP”) AND (“autoantibodies” OR “antibodies” OR “immunoglobulin G”) AND (“BP180” OR “BP230” OR “NC16A”) AND (“pemphigoid” OR “lichen planus pemphigoides” OR “mucous membrane pemphigoid” OR “autoimmune blistering disease”).

2.3. Selection Process

Two independent authors (D.D.F. and D.D.S.) screened articles by title and abstract for inclusion in the full-text stage. The full text of all potentially relevant articles was examined according to eligibility criteria. Duplicate references across different databases were identified and removed using Zotero version 7.0.26 (Vienna, VA, USA). Disagreements during the full text review process were primarily resolved through discussion between the reviewers. If consensus could not be reached, an independent third reviewer (M.P.) arbitrated the dispute. A flowchart depicting the study selection process is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Prisma flow chart.

2.4. Data Collection Process and Data Items

Extracted data were independently collected by the reviewers (D.D.F. and D.D.S.) using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. From each eligible study, the reviewers (D.D.F. and D.D.S.) extracted data on the first author name and year of publication, as well as age/sex, order of diagnosis (between clinical features of LP and serological findings of Pemphigoid), cutaneous clinical manifestations or involvement of other mucous membranes, localization of oral lesions, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) or indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), Enzyme-Linked Immunoassay (ELISA) testing and clinical outcomes.

2.5. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias in the included studies was evaluated using the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) tools (Table S2). CASP was selected for its capacity to systematically assess methodological quality and potential bias across different study designs, ensuring a standardized evaluation of methodological rigor.

2.6. Effect of Measures

The primary outcome was the clinical manifestations related to oral LPP. These included the extent of oral lesions, involvement of other tissues (skin, other mucous membranes), the presence or absence of underlying conditions whose pharmacological treatment might have triggered LPP, serological confirmation of the clinical conditions, and patient outcomes.

2.7. Synthesis Methods

A descriptive, qualitative analysis was carried out on the extracted data. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages, while qualitative findings were presented through a narrative synthesis. Since the evidence was limited to case series and case reports, performing a meta-analysis was not possible.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

A total of 67 articles were identified, of which 16 were duplicates, 20 did not include a diagnoses of LPP, 10 did not report oral manifestations of LPP, and 1 was excluded because it was not in English. articles were identified through manual search. The data from the remaining 20 articles were included in a table (Table 1) based on variables such as age/sex, order of diagnosis (between clinical features of LP and serological findings of Pemphigoid), cutaneous clinical manifestations or involvement of other mucous membranes, localization of oral lesions, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) or indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), Enzyme-Linked Immunoassay (ELISA) testing and clinical outcomes.

Table 1.

This table summarizes all documented cases of Oral Lichen Planus Pemphigoides according to the established search criteria.

3.2. Study Characteristic

The study evaluated 13 case reports, 4 retrospective studies, and 3 case series. The included studies were published between 1999 and 2025. Among patients with LPP, the mean age was 60.3 years (range 34–86). Sex was reported in 36 patients, of whom 11 (30.6%) were male and 25 (69.4%) female. With regard to the timing of onset between the typical clinicopathological features of LPP and those of pemphigoid, in 22 cases (61.1%) they occurred simultaneously, in 11 cases (30.6%) LPP preceded Autoimmune Bullous Disease (AIBD), and in 3 cases (8.3%) AIBD preceded LPP. Oral involvement was relatively homogeneous across clinical presentations, with oral erosions reported in 21 cases (42%), oral ulcers in 21 cases (42%), oral mucositis in 2 cases (4%), and other manifestations in 4 cases. Cutaneous involvement was observed in 27 patients (56%), combined cutaneous and other mucosal involvement in 8 patients (16.7%), exclusive involvement of other mucosal sites in 6 patients (12.6%), and isolated oral involvement in 7 patients (14.6%).

Eighteen patients (38%) with LPP were receiving medications potentially associated with the onset of lesions. Among these, 11 cases (56%) were related to oncologic immunotherapy, while the remaining 44% were associated with antihypertensive agents, statins, antidiabetic drugs, antivirals, and psychotropic medications. In the remaining 32 patients (62%), no evidence of drug-related triggering factors was identified. Regarding diagnostic investigations, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was positive in 36 patients (72%), with C3-only deposition detected in 3 patients (6%). Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) was positive in seven cases (14%). Immunoblotting revealed anti-BP180 antibodies in 13 patients (26%), anti-BP230 antibodies in 2 patients (4%), and other targets in 1 patient (2%). ELISA testing detected anti-BP180 antibodies in 34 patients (68%) and anti-BP230 antibodies in 6 patients (12%). As for patient outcomes, 21 patients (58.4%) achieved near-complete remission following pharmacologic treatment, 10 patients (27.8%) achieved complete remission, while in 3 patients (8.3%) the disease remained active.

4. Discussion

LPP is a heterogeneous disorder with features overlapping those of OLP and MMP [3,4]. Diagnosis is often challenging, as it requires histopathological findings consistent with OLP in combination with serological evidence of MMP [4]. Our systematic review indicates the presence of two distinct categories of LPP: drug-induced and non–drug-induced. Among diagnostic and serological tests, DIF and ELISA emerged as the most sensitive modalities. Corticosteroid therapy was effective in the majority of cases. In drug-induced LPP, withdrawal of the triggering medication, together with the aforementioned therapeutic approach, was consistently associated with clinical improvement.

The data reported in our study are consistent with the findings of previous individual studies on LPP. In fact, LPP is confirmed to be a condition affecting a wide age range, from young adults (around 30 years old) to individuals in the sixth and seventh decades of life [4]. As reported in the literature, women are more frequently affected than men [8]. Most authors describe synchronous oral lichen planus–like lesions associated with pemphigoid [8]. However, some authors report cases in which OLP represents the initial manifestation, with subsequent unmasking of LPP [8]. Remarkably, Mignona et al. even described two cases with the reverse sequence, where MMP evolved into LPP [2]. Another element fully in line with other studies is the consistent coexistence of oral and cutaneous lesions, which are almost invariably present [4]. Indeed, in the general case series of LPP, more than half of the patients show exclusively cutaneous involvement [4]. The involvement of mucous membranes, particularly the oral mucosa, is observed in a subset of patients (<50%) with LPP [4,8].

With regard to oral clinical manifestations, these are fairly homogeneous and not pathognomonic, as they consist of ulcerative–erosive lesions also observed in other clinical conditions such as pemphigus, OLP, pemphigoid, paraneoplastic pemphigus, and other oral mucositides [6,8].

Several studies have shown an association between drug exposure and LPP; however, effects upon drug re-exposure have not been documented, and further clinical validation is therefore required [1]. Although cases of drug-induced LPP, such as those triggered by ACE inhibitors, are well documented in the literature, with the advent of immunotherapy the proportion of drug-related cases is expected to increase [11,15,28]. Therefore, future studies should investigate the risk of LPP following immunotherapy in larger cohorts [9,15]. The diagnosis of LPP represents one of the most debated issues in the literature on this condition, due to its histological overlap with OLP and serological overlap with MMP [8]. Our study, in line with the literature, emphasizes that serology—particularly ELISA testing—is decisive for the diagnostic confirmation of this disease. Finally, treatment, which involves the use of systemic corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, IVIg, monoclonal antibodies, and, in drug-induced cases, discontinuation of the causative agent, appears to yield at least partially favorable outcomes [8].

5. Conclusions

The present study is intended as an initial step toward consolidating the available case studies of LPP, with the aim of facilitating a more precise diagnostic framework for this condition in the future. Nevertheless, it is subject to certain limitations, primarily related to the restricted amount of data and the predominance of case reports and case series within the current literature. In conclusion, we believe, in agreement with other authors, that due to its diagnostic complexity and heterogeneous clinical presentation, LPP is likely an underdiagnosed condition [8,29]. For this reason, in order to advance scientifically in the development and understanding of this disease, large multicenter studies are needed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathophysiology32040051/s1, Table S1: PRISMA checklist; Table S2: CASP RoB.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D.F. and M.P.; methodology, D.D.F.; validation, M.P., C.L. and A.L.; formal analysis, D.D.F. and D.D.S.; investigation, D.D.F. and A.C.; resources, D.D.F., D.D.S. and A.C.; data curation D.D.F.; writing—original draft preparation, D.D.F.; writing—review and editing, D.D.F. and M.P.; visualization, C.L. and A.L.; supervision, M.P. and D.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hübner, F.; Langan, E.A.; Recke, A. Lichen Planus Pemphigoides: From Lichenoid Inflammation to Autoantibody-Mediated Blistering. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, M.D.; Fortuna, G.; Leuci, S.; Stasio, L.; Mezza, E.; Ruoppo, E. Lichen planus pemphigoides, a possible example of epitope spreading. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 2010, 109, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, A.; Deo, K.; Masare, A.; Singh, S. Lichen Planus Pemphigoides: From Lichenoid to Bullous Disease. Ann. Afr. Med. 2025, 24, 481–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, D.; Mustari, A.P.; Chatterjee, D.; Mahajan, R.; Kumar, V.; Handa, S. Lichen Planus Pemphigoides: A Clinical, Histopathological, and Immunological Report of 12 Indian Patients. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2025, 16, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, S.; De Falco, D.; Petruzzi, M. Oral Manifestations in Paraneoplastic Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oral Dis. 2025, 31, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Falco, D.; Messina, S.; Petruzzi, M. Oral Paraneoplastic Pemphigus: A Scoping Review on Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Histo-Serological Profile. Antibodies 2024, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Falco, D.; Iaquinta, F.; Pedone, D.; Lucchese, A.; Di Stasio, D.; Petruzzi, M. Circulating Antibodies Against DSG1 and DSG3 in Patients with Oral Lichen Planus: A Scoping Review. Antibodies 2025, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combemale, L.; Bohelay, G.; Sitbon, I.-Y.; Ahouach, B.; Alexandre, M.; Martin, A.; Pascal, F.; Soued, I.; Doan, S.; Morin, F.; et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides with predominant mucous membrane involvement: A series of 12 patients and a literature review. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1243566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, G.N.; Agarwal, P.; Rao, B.K. Lichen Planus Pemphigoides as an Adverse Reaction to Medication Use: A Retrospective Analysis of Commonly Implicated Medication Triggers Using the FDA Adverse Events Reporting Database. Exp. Dermatol. 2025, 34, e70103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, M.M.; Ashi, S.; Puiu, T.; Reimer, D.; Sokumbi, O.; Soltani, K.; Onajin, O. Lichen Planus Pemphigoides Associated With PD-1 and PD-L1 Inhibitors: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2022, 44, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, J.; Deng, S.; Wu, L.; Li, W.; Ye, T.; Wu, F.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, H. Lichen planus pemphigoides induced by anti-PD-1 antibody: A case only involved in oral mucosa with excellent topical treatment efficiency. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2024, 51, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch’eN, P.Y.; Song, E.J. Lichen planus pemphigoides successfully treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2023, 31, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, M.; Baldissano, M.; King, L.; Gaspari, A.A. Successful Use of Rituximab and Intravenous Gamma Globulin to Treat Checkpoint Inhibitor- Induced Severe Lichen Planus Pemphigoides. Skinmed 2020, 18, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ney, Z.C.; Nicholson, L.T.; Madigan, L.M. Immunotherapy-associated lichen planus pemphigoides successfully treated with intravenous immune globulin—Two illustrative cases. JAAD Case Rep. 2024, 53, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Hara, S.; Taniike, N. Pembrolizumab-induced oral lichen planus pemphigoides with mucous membrane pemphigoid preceding lichen planus. J. Dent. Sci. 2025, 20, 726–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Howard, T.D.; Fattah, Y.H.; Adams, A.D.; Hanly, A.J.; Karai, L.J. Lichen Planopilaris Pemphigoides: A Novel Bullous Dermatosis Due to Programmed Cell Death Protein-1 Inhibitor Therapy. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2023, 45, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaaouani, R.; Hali, F.; Marnissi, F.; Meftah, A.; Chiheb, S. A Generalized Form of Lichen Planus Pemphigoid Induced by an Oral Antidiabetic. Cureus 2022, 14, e31094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wat, M.; Mollanazar, N.K.; Ellebrecht, C.T.; Forrestel, A.; Elenitsas, R.; Chu, E.Y. Lichen-planus-pemphigoides-like reaction to PD-1 checkpoint blockade. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2022, 49, 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondhia, C.; Kaur, C.; Mee, J.; Natkunarajah, J.; Singh, M. Lichen Planus Pemphigoides Mimicking Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2019, 41, e144–e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.H.; Yun, S.J.; Lee, S.C.; Lee, J.B. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2015, 40, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, A.; Kodera, M.; Yamaoka, T.; Iwata, Y.; Usuda, T.; Ohzono, A.; Yasukochi, A.; Koga, H.; Ishii, N.; Hashimoto, T. A case of lichen planus pemphigoides with autoantibodies to the NC 16a and C-terminal domains of BP 180 and to desmoglein-1. Br. J. Dermatol. 2014, 171, 1230–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washio, K.; Nakamura, A.; Fukuda, S.; Hashimoto, T.; Horikawa, T. A Case of Lichen Planus Pemphigoides Successfully Treated with a Combination of Cyclosporine A and Prednisolone. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2013, 5, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buijsrogge, J.; Hagel, C.; Duske, U.; Kromminga, A.; Vissink, A.; Kloosterhuis, A.; van der Wal, J.; Jonkman, M.; Pas, H. IgG antibodies to BP180 in a subset of oral lichen planus patients. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2007, 47, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.I.; Fitzpatrick, J.E.; Kornfeld, B.W.; Fitzpatrick, J.E. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with ramipril. Int. J. Dermatol. 2006, 45, 1453–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma-Oyama, Y.; Powell, A.M.; Albert, S.; Oyama, N.; Bhogal, B.S.; Black, M.M. Lichen planus pemphigoides evolving into pemphigoid nodularis: Clinical variants of pemphigoid. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2003, 28, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaria, M.; Salomon, D.; Jaunin, F.; Friedli, A.; Saurat, J.H.; Borradori, L. IgG Autoantibodies from a Lichen planus pemphigoides Patient Recognize the NC16A Domain of the Bullous Pemphigoid Antigen 180. Dermatology 1999, 199, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillikens, D.; Caux, F.; Mascaro, J.M.; Wesselmann, U.; Schmidt, E.; Prost, C.; Callen, J.P.; Bröcker, E.-B.; Diaz, L.A.; Giudice, G.J. Autoantibodies in Lichen Planus Pemphigoides React with a Novel Epitope within the C-Terminal NC16A Domain of BP180. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1999, 113, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Qin, X.; Zhang, R. Lichen Planus Pemphigoides Induced by Camrelizumab in Combination With Lenvatinib. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2024, 46, 332–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzi, M.; della Vella, F.; Squicciarini, N.; Lilli, D.; Campus, G.; Piazzolla, G.; Lucchese, A.; van der Waal, I. Diagnostic delay in autoimmune oral diseases. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 2614–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).