Secondary Prostate Lymphoma Mimicking Prostate Cancer Successfully Managed by Transurethral Resection to Relieve Urinary Retention

Abstract

1. Introduction

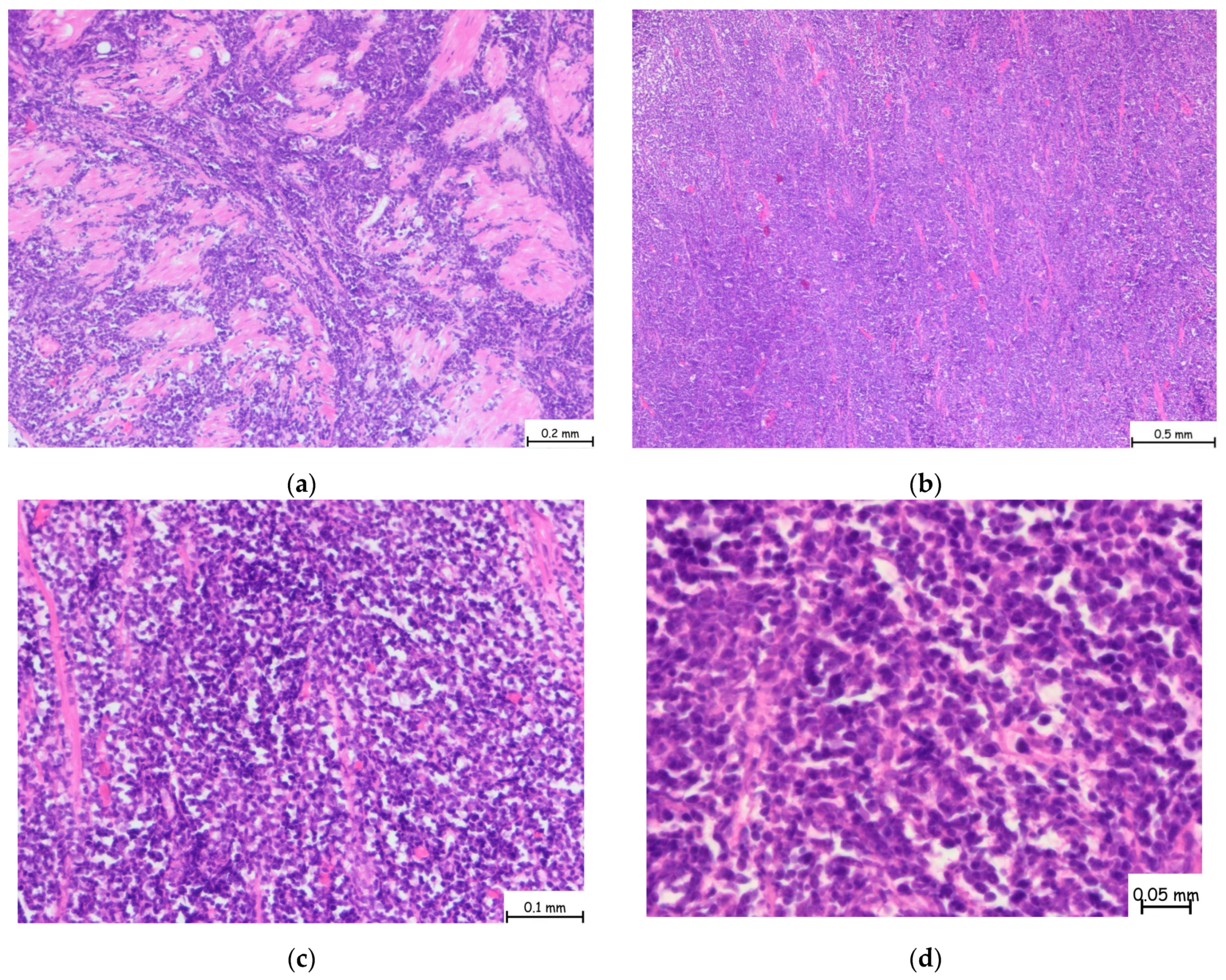

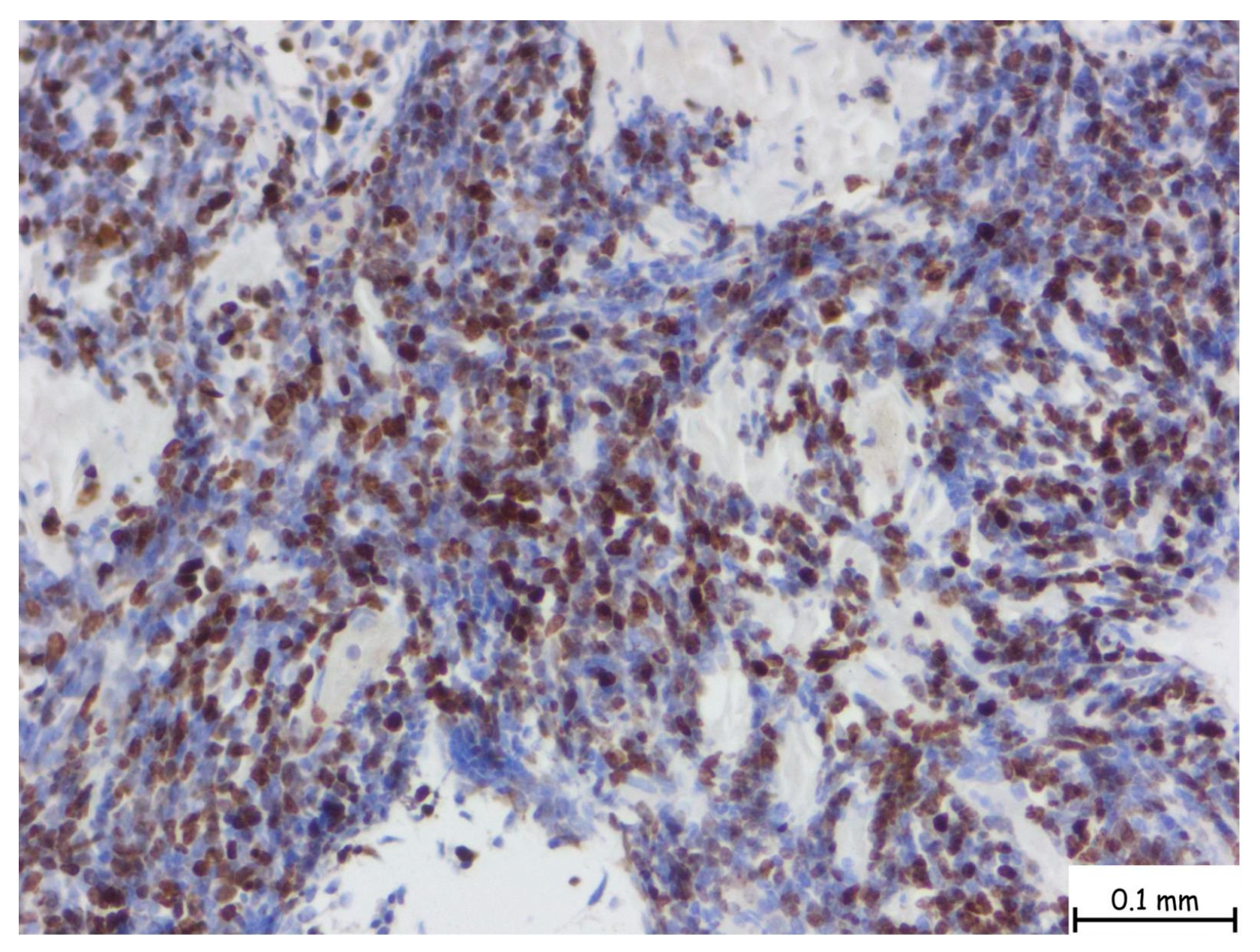

2. Detailed Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Humphrey, P.A. Histological variants of prostatic carcinoma and their significance. Histopathology 2012, 60, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surintrspanont, J.; Zhou, M. Prostate Pathology: What is New in the 2022 WHO Classification of Urinary and Male Genital Tumors? Pathologica 2023, 115, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morichetti, D.; Mazzucchelli, R.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Cheng, L.; Scarpelli, M.; Kirkali, Z.; Montorsi, F.; Montironi, R. Secondary neoplasms of the urinary system and male genital organs. BJU Int. 2009, 104, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D.T.; Koya, S.; Dogga, S.; Kumar, A. Mantle Cell Lymphoma. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Monga, N.; Garside, J.; Quigley, J.; Hudson, M.; O’Donovan, P.; O’Rourke, J.; Tapprich, C.; Parisi, L.; Davids, M.S.; Tam, C. Systematic literature review of the global burden of illness of mantle cell lymphoma. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2020, 36, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.F.; Zhou, J.; Tawfiq, R.K.; Tun, H.W.; Munoz, J.L.; Paludo, J.; Moustafa, M.A.; Hwang, S.R.; Okcu, I.; Diefenbach, C.S.; et al. Association of Sex, Race and Ethnicity with Clinical Characteristics and Survival Outcomes of Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A National Cancer Database Study. Blood 2024, 144, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdussalam, A.; Gerridzen, R.G. Mantle cell lymphoma of the prostate. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2013, 3, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chu, P.G.; Huang, Q.; Weiss, L.M. Incidental and Concurrent Malignant Lymphomas Discovered at the Time of Prostatectomy and Prostate Biopsy: A Study of 29 Cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2005, 29, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurioli, A.; Marson, F.; Pisano, F.; Soria, F.; Lorenzo, D.; Pacchioni, D.; Frea, B.; Gontero, P. A Rare Case of Primary Mantle Cell Lymphoma of the Prostate: Clinical Aspects and Open Problems. Urol. J. 2013, 80, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, S.; Uzundal, H.; Soydas, T.; Ozayar, A.; Ardicoglu, A.; Kilicarslan, A. A Rare Prostate Pathology: Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Grand. J. Urol. 2021, 1, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, J.D.; Foster, C.S. Mantle Cell Lymphoma Involving the Prostate with Features of Granulomatous Prostatitis: A Case Report. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 20, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milburn, P.A.; Cable, C.T.; Trevathan, S.; El Tayeb, M.M.E. Mantle Cell Lymphoma of the Prostate Gland Treated with Holmium Laser Enucleation. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2017, 30, 338–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bostwick, D.G.; Iczkowski, K.A.; Amin, M.B.; Discigil, G.; Osborne, B. Malignant lymphoma involving the prostate: Report of 62 cases. Cancer 1998, 83, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedby, K.E.; Hjalgrim, H. Epidemiology and etiology of mantle cell lymphoma and other non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2011, 21, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsson, A.; Dahle, N.; Jerkeman, M. Marked improvement of overall survival in mantle cell lymphoma: A population based study from the Swedish Lymphoma Registry. Leuk. Lymphoma 2011, 52, 1929–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zein, T.A.; Huben, R.; Lane, W.; Pontes, J.E.; Englander, L.S. Secondary Tumors of the Prostate. J. Urol. 1985, 133, 615–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chim, C.S.; Loong, F.; Yau, T.; Ooi, G.C.; Liang, R. Common Malignancies with Uncommon Sites of Presentation: CASE 2. MANTLE-CELL LYMPHOMA OF THE PROSTATE GLAND. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 4456–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doshi, K.; Chandran, A.; Li, Y.; Bitran, J. Mantle Zone Lymphoma with Prostate Gland Enlargement: A Case Report. Cureus 2022, 14, e32045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasmeen, S.; Ahmad, W.; Waqas, O.; Hameed, A. Primary Prostatic Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. J. Cancer Allied Spec. 2021, 8, e439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, M.; Liu, Y. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the prostate: A case report and review of the literature. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 15, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yin, G.; Duan, L.; Li, W.; Jiang, X. A new marker, SOX11, aids the diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma in the prostate: A case report. Oncol. Lett. 2012, 4, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.B.; Burns, B.; Gerridzen, R.; Jagt, R.V.D. Coexisting Mantle Cell Lymphoma and Prostate Adenocarcinoma. Case Rep. Med. 2014, 2014, 247286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petkovic, I.; Stojnev, S.; Krstic, M.; Pejcic, I.; Vrbic, S. Synchronous mantle cell lymphoma and prostate adenocarcinoma-is it just a coincidence? Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2016, 73, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tvrdíková, E.; Křen, L.; Kubolková, A.S.; Pacík, D. Mantle cell lymphoma diagnosed from radical prostatectomy for prostate adenocarcinoma: A case report. Cesk Patol. 2019, 55, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Year | Age | Primary/Secondary | Symptom(s) | Diagnostic Method | Treatment | PSA | Associated Cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chim CS [17] | 2003 | 73 | Secondary | Acute urinary retention | Prostate biopsy | Chemotherapy | - | None |

| Chu PG [8] | 2005 | 65/80 | Secondary/Secondary | No documented LUTS | Prostate biopsy TUR-P | No documented TUR-P | - - | None None |

| Abdussalam A [7] | 2013 | 82 | Secondary | Bladder outlet obstruction | TUR-P | TUR-P | 2.4 | None |

| Coyne JD [11] | 2012 | 60 | Secondary | Prostatism + recurrent urinary tract infection | Prostate biopsy | Not documented | - | None |

| Chen B [21] | 2012 | 83 | Primary | LUTS, urinary retention | TUR-P | TUR-P | 3.2 ng/mL | Bladder cancer |

| Gurioli A [9] | 2013 | 83 | Primary | Gross hematuria + weight loss | Transvesical adenomectomy | Transvesical adenomectomy | - | Renal cancer |

| Rajput AB [22] | 2014 | 74 | Secondary | Elevated PSA levels | Prostate biopsy | Chemotherapy | 17.16 ng/mL | Prostate adenocarcinoma |

| Petkovic I [23] | 2016 | 64 | Secondary | Fatigue, splenomegaly, elevated PSA level | Prostate biopsy | Chemotherapy + Androgen Deprivation Therapy | 52 ng/mL | Prostate adenocarcinoma |

| Milburn PA [12] | 2017 | 59 | Secondary | Progressive LUTS | HoLEP | HoLEP | 1.2 ng/mL | None |

| Tvrdíková E [24] | 2019 | 64 | Secondary | Elevated PSA level | Radical prostatectomy | Radical prostatectomy | 5.9 ng/mL | Prostate cancer |

| Ünal S [10] | 2021 | 70 | Primary | LUTS + elevated PSA level | Prostate biopsy | Chemotherapy | 8.2 ng/mL | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reman, L.-T.; Malau, O.; Porav-Hodade, D.; Chibelean, C.; Vida, A.-O.; Todea, C.; Ghirca, V.; Laslo, A.; Gherasim, R.-D.; Vascul, R.; et al. Secondary Prostate Lymphoma Mimicking Prostate Cancer Successfully Managed by Transurethral Resection to Relieve Urinary Retention. Pathophysiology 2025, 32, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathophysiology32030038

Reman L-T, Malau O, Porav-Hodade D, Chibelean C, Vida A-O, Todea C, Ghirca V, Laslo A, Gherasim R-D, Vascul R, et al. Secondary Prostate Lymphoma Mimicking Prostate Cancer Successfully Managed by Transurethral Resection to Relieve Urinary Retention. Pathophysiology. 2025; 32(3):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathophysiology32030038

Chicago/Turabian StyleReman, Lorand-Tibor, Ovidiu Malau, Daniel Porav-Hodade, Calin Chibelean, Arpad-Oliver Vida, Ciprian Todea, Veronica Ghirca, Alexandru Laslo, Raul-Dumitru Gherasim, Rares Vascul, and et al. 2025. "Secondary Prostate Lymphoma Mimicking Prostate Cancer Successfully Managed by Transurethral Resection to Relieve Urinary Retention" Pathophysiology 32, no. 3: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathophysiology32030038

APA StyleReman, L.-T., Malau, O., Porav-Hodade, D., Chibelean, C., Vida, A.-O., Todea, C., Ghirca, V., Laslo, A., Gherasim, R.-D., Vascul, R., Katona, O.-B., Hagău, R.-D., & Martha, O. (2025). Secondary Prostate Lymphoma Mimicking Prostate Cancer Successfully Managed by Transurethral Resection to Relieve Urinary Retention. Pathophysiology, 32(3), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathophysiology32030038