Telomerase Activity in Melanoma: Impact on Cancer Cell Proliferation Kinetics, Tumor Progression, and Clinical Therapeutic Strategies—A Scoping Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria and Exclusion Criteria

- Rapid therapeutic advances: The landscape of telomerase-targeted therapies in melanoma has evolved dramatically since 2020, with the emergence of novel agents (e.g., 6-thio-dG), CRISPR/Cas9 editing approaches, and next-generation immunotherapies. Our aim was to capture the most current evidence relevant to contemporary clinical practice.

- Recent molecular discoveries: Key mechanistic insights, including the EXTEND algorithm, pan-cancer telomere maintenance mechanism (TMM) phenotypes, and TPP1 promoter mutations, were published within this timeframe and represent substantive advances over earlier work.

- Selective inclusion of foundational studies: We explicitly included select studies from 2015 to 2019 (as stated in our inclusion criteria in Section 2.1) when they provided essential mechanistic insights that were not superseded by more recent literature. For example, foundational work on TERT promoter mutations and drug resistance pathways remains clinically relevant and continues to be cited in current research.

- Scoping review purpose: Unlike exhaustive systematic reviews that aim for comprehensive historical coverage, scoping reviews map the current state of knowledge and identify gaps to guide future research. Our temporal focus aligns with this objective. Therefore, regarding the relatively low number of studies (n = 16), this reflects the novelty of specific therapeutic targets and the scarcity of direct doubling time data in this specific context, which is a key finding in itself that highlights the research gap we aim to explore.

- Mapping conceptual frameworks: Reviews by Ali et al. and Tao et al. synthesized emerging therapeutic frameworks, e.g., the TICCA (Transient, Immediate, Complete and Combinatory Attack) strategy, that have not yet been validated in primary studies but represent important conceptual advances in the field.

- Tracing primary evidence: Where reviews cited critical primary data, we systematically traced and reviewed the original articles to ensure accuracy. For example, mutation frequency data and mechanistic pathways were verified against primary sources.

- Scoping review methodology: The Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines for scoping reviews explicitly state that including reviews alongside primary studies is appropriate when the goal is to comprehensively map available knowledge rather than synthesize effect sizes.

2.2. Quality Assessment and Data Analysis (Figure 1 and Tables S1–S3)

3. Results

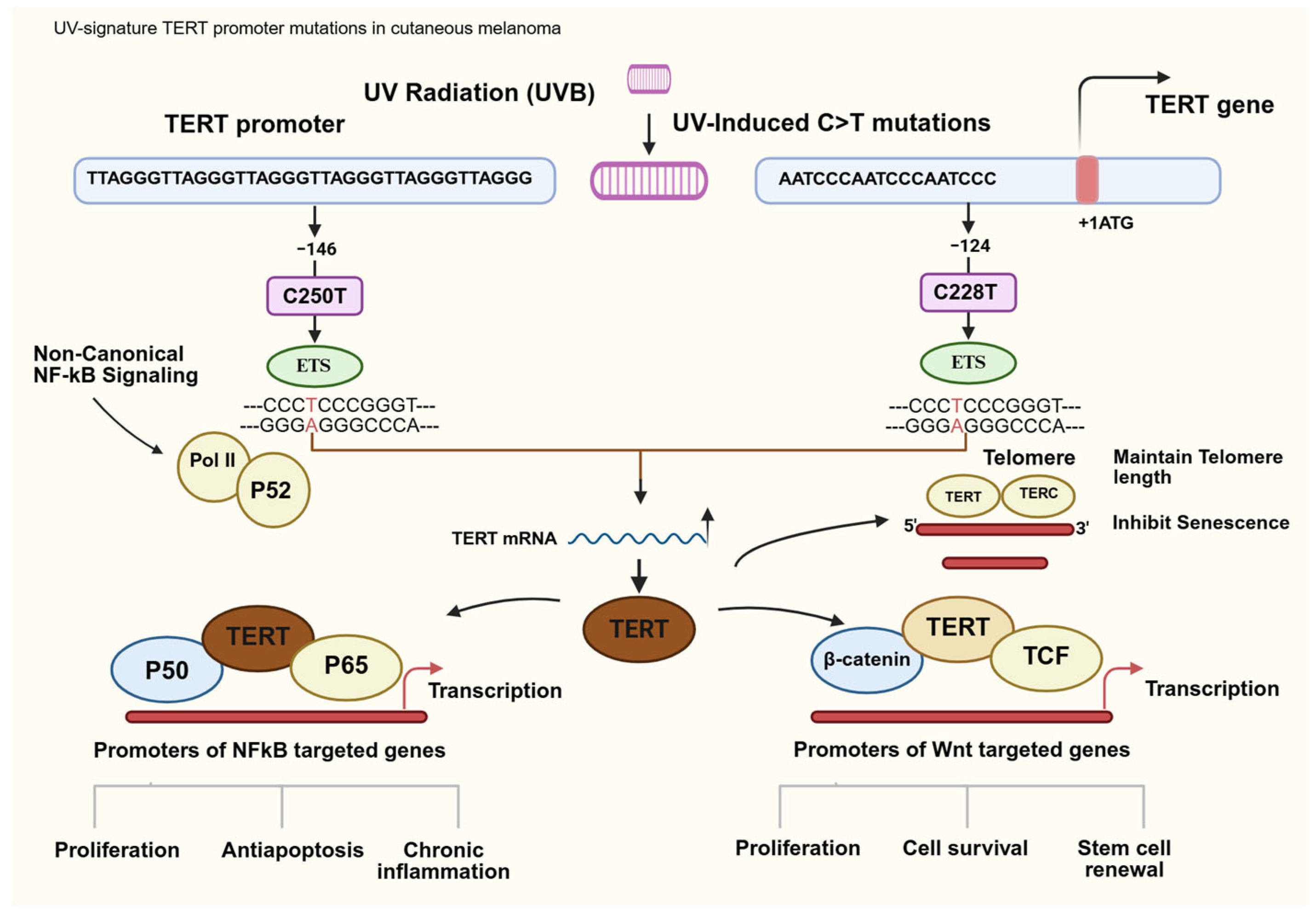

3.1. TERT Promoter Mutations as Drivers of Proliferation

3.2. Diagnostic and Prognostic Significant of Telomerase in Melanoma

3.3. Telomere Maintenance Mechanisms and Pathway Analysis

- -

- C250T variant (associated with 5.7-fold-increased TERT expression):

- Progression-free survival (PFS): 5 months.

- Overall survival (OS): 36 months.

- Poorest prognosis among all groups.

- -

- C228T variant (associated with 2.1-fold-increased TERT expression):

- PFS: 23 months.

- OS: 106 months.

- Intermediate prognosis.

- -

- Wide-type (no TERT promoter mutation):

- PFS: 55 months.

- OS: 223 months.

- Best prognosis.

3.4. Therapeutic Targeting of Telomerase in Melanoma

3.5. TERT Genomic Alteration in Melanoma Culled from cBioportal-Based Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of This Study

4.2. Future Research

- *

- Prospective clinical trials directly measuring telomerase enzymatic activity alongside quantified cell population doubling times are essential to establish correlations between telomerase expression, telomere dynamics, and proliferation kinetics in vivo.

- *

- Research should examine the mutation-specific effects of TERT promoter variants (C250T versus C228T) in influencing telomerase activity and cellular phenotypes, as variant level biomarkers may better predict therapeutic response.

- *

- Investigators should characterize the extratelomeric functions of telomerase, including its role in mitochondrial metabolism, NF-kB signaling, and drug efflux transportation to identify synergistic opportunities for combined inhibition strategies.

- *

- Comparative efficacy studies should evaluate emerging telomerase-directed strategies, including 6-thio-dG, imetelstat, G-quadruplex stabilizers, and the TICCA framework, within controlled clinical settings

- *

- Future research should clarify the interplay between telomerase-dependent and ALT pathways in determining progression and resistance.

- *

- Research must explore biomarker-driven approaches integrating telomere length, TERT mutation analysis, and immune checkpoint expression to guide personalized intervention strategies.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| ALT | Alternative lengthening of telomeres |

| BRAF | v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B |

| BRAF V600E | A common activating mutation in the BRAF gene that leads to constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factors receptor |

| EXTEND | Expression based telomerase enzymatic activity detection |

| ETS | E26-transformation-specific (Erythroblast-transformation-specific) |

| G1-S/G2-M phases | Cell-cycle phases |

| GABP | GA-binding protein |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| hTERT | Human telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MEK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| miRNA | Micro-ribonucleic acid |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| MSI-H | Microsatellite instability-high |

| N/A | Not available |

| NF-kB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NF1 | Neurofibromin |

| NRAS | Neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog |

| PMCA4 | Plasma membrane calcium ATpase4 |

| PSF | Pathway signal flow |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SEER | Surveillance, epidemiology and end results |

| TCGA | The cancer Genome atlas |

| TEL | Telomerase-dependent pathway (telomerase-positive phenotype) |

| TERT | Telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| TF | Transcription factor |

| TICCA | Transient, immediate, complete and combinatory attack |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TMM | Telomere maintenance mechanism |

| TPP1 | Telomerase processivity protein 1 |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| WT | Wild type |

References

- Okobi, O.E.; Johnson, A.; Patel, R.; Nguyen, T.; Smith, L.; Brown, K.; Garcia, M.; Lee, S.; Thompson, J.; Davis, R.; et al. Trends in melanoma incidence, prevalence, stage at diagnosis, and survival: An analysis of the United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) Database. Cureus 2024, 16, e70697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagle, N.S.; Nogueira, L.; Devasia, T.P.; Mariotto, A.B.; Yabroff, K.R.; Islami, F.; Jemal, A.; Alteri, R.; Ganz, P.A.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 308–340, Erratum in CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 683. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.70036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, P.; Schubert, C.; Tamm, E.R.; Reichrath, J.; Tilgen, W.; Parwaresch, R. Telomerase activity in melanocytic lesions: A potential marker of tumor biology. Am. J. Path. 2000, 156, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, R.D.; D’Atri, S.; Pagani, E.; Faraggiana, T.; Lacal, P.M.; Jansen, B.; Herlyn, M.; Shay, J.W.; Wright, W.E.; Bacchetti, S.; et al. Progressive increase in telomerase activity from benign melanocytic conditions to malignant melanoma. Neoplasia 1999, 1, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, C.N.; Jezzard, S.; Silver, A.; MacKie, R.M.; MacKie, R.M.; Newbold, R.F. Telomerase activity in melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer. Br. J. Cancer 1999, 79, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, S.; Figl, A.; Rachakonda, P.S.; Fischer, C.; Sucker, A.; Gast, A.; Kadel, S.; Moll, I.; Nagore, E.; Hemminki, K.; et al. TERT promoter mutations in familial and sporadic melanoma. Science 2013, 339, 959–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.W.; Hodis, E.; Xu, M.J.; Kryukov, G.V.; Chin, L.; Garraway, L.A. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science 2013, 339, 957–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, W.; Huang, Z.; Yang, F.; et al. TERT promoter mutations and telomerase in melanoma. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 6300329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.W.; Piatyszek, M.A.; Prowse, K.R.; Harley, C.B.; West, M.D.; Ho, P.L.; Coviello, G.M.; Wright, W.E.; Weinrich, S.L.; Shay, J.W.; et al. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science 1994, 266, 2011–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, E.H.; Epel, E.S.; Lin, J. Human telomere biology: A contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science 2015, 350, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J.W.; Zou, Y.; Hiyama, E.; Wright, W.E.; Bacchetti, S.; Harley, C.B.; Kim, N.W.; Prowse, K.R.; Ho, P.L.; West, M.D.; et al. Telomerase and cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincz, L.F.; Scorgie, F.E.; Garg, M.B.; Ackland, S.P.; Sakoff, J.A.; Hamilton, C.S.; Seldon, M.; Enjeti, A.K.; Spencer, A.; Avery, S.; et al. Quantification of hTERT splice variants in melanoma by SYBR Green real-time polymerase chain reaction indicates a negative regulatory role for the β-deletion variant. Neoplasia 2008, 10, 1131–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagoev, K.B. Cell proliferation in the presence of telomerase. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristofari, G.; Lingner, J. Telomere length homeostasis requires that telomerase levels are limiting. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noureen, N.; Wu, S.; Lv, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Q.; et al. Integrated analysis of telomerase enzymatic activity unravels an association with cancer stemness and proliferation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delyon, J.; Lebbé, C.; Dumaz, N.; Mourah, S.; Battistella, M.; Vagner, S.; Avril, M.F.; Saiag, P.; Funck-Brentano, E.; Dupin, N.; et al. TERT expression induces resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors in BRAF-mutated melanoma in vitro. Cancers 2023, 15, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-García, L.; Ruano, Y.; Martínez-Illescas, R.B.; Cubo, R.; Sánchez, P.J.; Lobo, V.J.S.-A.; Falkenbach, E.R.; Romero, P.O.; Garrido, M.C.; Peralto, J.L.R.; et al. pTERT C250T mutation: A potential biomarker of poor prognosis in metastatic melanoma. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.H.; Walter, M. Combining old and new concepts in targeting telomerase for cancer therapy: Transient, immediate, complete and combinatory attack (TICCA). Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterres, A.N.; Villanueva, J. Targeting telomerase for cancer therapy. Oncogene 2020, 39, 5811–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinska, N.; Romaniuk, A.; Paszel-Jakubowska, A.; Toton, E.; Kopczynski, P.; Rubis, B. Telomerase and drug resistance in cancer. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 4121–4132. [Google Scholar]

- Boccardi, V.; Marano, L. Aging, cancer, and inflammation: The telomerase connection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, H.-Y.; Zhao, C.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, W.-J.; Zhen, Y.-S. Targeting telomere dynamics as an effective approach for the development of cancer therapeutics. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 3805–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welfer, G.A.; Freudenthal, B.D. Recent advancements in the structural biology of human telomerase and their implications for improved design of cancer therapeutics. NAR Cancer 2023, 5, zcad010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakobyan, M.; Binder, H.; Arakelyan, A. Pan-cancer analysis of telomere maintenance mechanisms. J. Biol Chem. 2024, 300, 107392. [Google Scholar]

- Sanford, S.L.; Opresko, P.L. UV light-induced dual promoter mutations dismantle the telomeric guardrails in melanoma. DNA Repair 2023, 122, 103446. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, L.W.; Mender, I.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Hammond, M.R.; Ope, O.; Cheng, C.; Vasilopoulos, T.; Randell, S.; Sadek, N.; et al. Induction of telomere dysfunction prolongs disease control of therapy-resistant melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 4771–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.J.; Schiemann, W.P. Telomerase in cancer: Function, regulation, and clinical translation. Cancers 2022, 14, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chowdhury, S. Emerging mechanisms of telomerase reactivation in cancer. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylie, T.; Jemal, M.; Baye, G.; Getinet, M.; Amare, G.A.; Adugna, A.; Abebaw, D.; Teffera, Z.H.; Tegegne, B.A.; Gugsa, E.; et al. The role of telomere and telomerase in cancer and novel therapeutic target: Narrative review. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1542930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyra, P.; Krasowska, D.; Pitucha, M. New potential agents for malignant melanoma treatment—Most recent studies 2020–2022. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun-On, P.; Hinchie, A.M.; Beale, H.C.; Silva, A.A.G.; Rush, E.; Sander, C.; Connelly, C.J.; Seynnaeve, B.K.N.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Vaske, O.M.; et al. TPP1 promoter mutations cooperate with TERT promoter mutations to lengthen telomeres in melanoma. Science 2022, 378, 664–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, R.J.; Rube, H.T.; Kreig, A.; Mancini, A.; Fouse, S.D.; Nagarajan, R.P.; Choi, S.; Hong, C.; He, D.; Pekmezci, M.; et al. The transcription factor GABP selectively binds and activates the mutant TERT promoter in cancer. Science 2015, 348, 1036–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shay, J.W.; Wright, W.E. Telomeres and telomerase: Three decades of progress. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesare, A.J.; Reddel, R.R. Alternative lengthening of telomeres: Models, mechanisms and implications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, F.P.; Wei, W.; Tang, M.; Martinez-Ledesma, E.; Hu, X.; Amin, S.B.; Akdemir, K.C.; Seth, S.; Song, X.; Wang, Q.; et al. Systematic analysis of telomere length and somatic alterations in 31 cancer types. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhari, V.K.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, S.; Mishra, R. Shelterin complex gene: Prognosis and therapeutic vulnerability in cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2021, 26, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, M.A.; Ansari, S.A.; Alqahtani, M.H.; Shay, J.W. Roles of telomeres and telomerase in cancer, and advances in telomerase-targeted therapies. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukoshi, E.; Kaneko, S. Telomerase-targeted cancer immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.; Degen, C.; Moradi, N.; Stacey, D. Nurse-led telehealth interventions for symptom management in patients with cancer receiving systemic or radiation therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7119–7132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, A.; Manns, M.P.; Rudolph, K.L. Telomeres, telomerase and cancer: An endless search to target the ends. Cell Cycle 2004, 3, 1136–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallarelli, A.F.; Rachakonda, P.S.; André, J.; Heidenreich, B.; Riffaud, L.; Bensussan, A.; Kumar, R.; Dumaz, N. TERT promoter mutations in melanoma render TERT expression dependent on MAPK pathway activation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 53127–53136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, B.; Rachakonda, P.S.; Hosen, I.; Volz, F.; Hemminki, K.; Weyerbrock, A.; Kumar, R. TERT promoter mutations and telomere length in adult malignant gliomas and recurrences. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 10617–10633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leão, R.; Lee, D.; Figueiredo, A.; Hermanns, T.; Wild, P.; Komosa, M.; Lau, I.; Mistry, M.; Nunes, N.M.; Price, A.J.; et al. Combined genetic and epigenetic alterations of the TERT promoter affect clinical and biological behavior of bladder cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J.W. Role of telomeres and telomerase in aging and cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardin, C.; Laheurte, C.; Puzenat, E.; Boullerot, L.; Ramseyer, M.; Marguier, A.; Jacquin, M.; Godet, Y.; Aubin, F.; Adotevi, O. Naturally occurring telomerase-specific CD4 T-cell immunity in melanoma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aamdal, E.; Inderberg, E.M.; Ellingsen, E.B.; Rasch, W.; Brunsvig, P.F.; Aamdal, S.; Heintz, K.M.; Vodák, D.; Nakken, S.; Hovig, E.; et al. Combining a universal telomerase based cancer vaccine with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma—Five-year follow up of a phase I/IIa trial. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 663865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Author/ Reference | Purpose | Settings | Sample Size | Study Design | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boccardi [21] | To review the relationship between telomeres/telomerase, aging, inflammation and cancer. | Division of Gerontology & Geriatrics, U. Perugia (Italy) and affiliated medical/surgical depts, Poland. | N/A | Narrative review. | Describes how telomere shortening and telomerase dysregulation link chronic inflammation, aging and cancer, and summarizes telomerase-targeted therapies. |

| Guo [8] | To review the role of TERT promoter mutations and telomerase in melanoma biology, prognosis and treatment. | Dept of Oncology/Plastic & Burns Surgery, 1st Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical U., China. | N/A | Narrative review. | Describes how hotspot TERT RT promoter mutations increase TERT/telomerase activity, link to aggressive disease and poor prognosis, Outlines emerging telomerase-targeted and combination therapies in melanoma. |

| Lipinska [20] | To review the mechanisms linking telomerase activity with drug resistance in cancer. | Dept of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics, Poznan U. of Medical Sciences, Poland. | N/A | Narrative review. | Describes how hTERT activation, mitochondrial translocation and vault/ABC transporter pathways contribute to chemoresistance and cancer cell survival. |

| Ali [18] | To summarize classical and novel approaches in telomerase-targeted cancer therapy and propose the TICCA concept. | Institute of Laboratory Medicine, Charité Berlin & University of Rostock, Germany. | N/A | Narrative review. | Reviews mechanisms of telomerase inhibition and introduces the TICCA strategy (Transient, Immediate, Complete, and Combinatory Attack) as a combined therapeutic model integrating CRISPR/Cas9, telomere deprotection, and hybrid inhibitors for improved long-term cancer control. |

| Tao [22] | To review the therapeutic potential of targeting telomere dynamics in cancer. | Institute of Medicinal Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing. | N/A | Narrative review. | Summarizes telomere- and telomerase-targeted drugs in clinical and preclinical stages, highlighting their chemotherapeutic and immunotherapeutic potential and integration into nanomedicine systems. |

| Welfer [23] | To summarize recent advances in human telomerase structural biology and implications for drug design. | U. Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, USA. | N/A | Narrative review. | Reviews new cryo-EM structures of human telomerase, elucidating mechanisms of recruitment, telomere synthesis, and structural targets for rational inhibitor development. |

| Hakobyan [24] | To perform a pan-cancer analysis of telomere maintenance mechanisms (TMM) across 33 cancer types. | Institute of Molecular Biology NAS RA, Armenia; U. Leipzig, Germany. | 11,123 TCGA samples. | Bioinformatics-based pan-cancer analysis. | Identified 5 distinct TMM phenotypes integrating telomerase (TEL) and ALT pathways; their coactivation correlated with worse survival and higher activity in MSI-H tumors. |

| Sanford [25] | To discuss how UV-induced promoter mutations in TERT and TPP1 cooperate to bypass telomere-based barriers in carcinogenesis. | U. Pittsburgh, USA. | N/A | Commentary/mechanistic review. | Highlights TERT and TPP1 promoter mutations as sequential UV-driven “hits” that cooperate to sustain telomere maintenance and melanoma progression. |

| Blanco-García [17] | To assess pTERT mutations/methylation in tissue and plasma of advanced melanoma and relate them to TERT expression and prognosis. | Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain. | 53 pts (88 tumors; 25 plasma). | Retrospective cohort. | C250T mutation linked to higher TERT expression and poor survival; pTERT hypermethylation enriched in WT tumors. |

| Zhang [26] | To test telomerase-targeted nucleoside 6-thio-dG in therapy-resistant melanoma. | The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, USA. | Several human melanoma cell lines and xenografts. | Preclinical experimental study. | 6-thio-dG induces telomere dysfunction, apoptosis, and tumor control in therapy-resistant melanoma. |

| Robinson [27] | To review telomerase functions, regulation, and clinical applications in cancer. | Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, Case Western Reserve U., USA. | N/A | Comprehensive review. | Summarizes telomerase’s telomeric and extratelomeric roles, regulatory mechanisms, and its translational potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target. |

| Delyon [16] | To assess how TERT expression influences resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors in BRAF-mutated melanoma. | INSERM U976 and Hospital Saint Louis, U. Paris Cité, France. | 48 patients + in vitro cell lines. | Translational and in vitro study. | High TERT expression correlated with reduced response to BRAF/MEK inhibitors; TERT overexpression reactivated MAPK pathway independently of telomere maintenance. |

| Sharma [28] | To summarize emerging molecular mechanisms underlying hTERT promoter–driven telomerase reactivation in cancer. | CSIR-Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology, New Delhi, India. | N/A | Narrative review. | Describes how hTERT promoter mutations, chromatin looping, and G-quadruplex destabilization cooperatively reactivate telomerase across cancers. |

| Baylie [29] | To review telomere and telomerase structure, function, and their role as therapeutic targets in cancer. | Debre Markos U., Ethiopia. | N/A | Narrative review. | Summarizes telomerase biology and emerging therapeutic strategies, including antisense oligonucleotides, G-quadruplex stabilizers, and telomerase-targeted immunotherapies. |

| Kozyra [30] | To review newly synthesized anti-melanoma agents and their molecular targets (2020–2022). | Medical U. Lublin, Poland. | N/A | Systematic literature review. | Summarizes recent compounds targeting MAPK, PI3K–AKT, and ion-channel pathways; highlights benzimidazole-based telomerase inhibitors among emerging therapeutic candidates. |

| Chun-on [31] | To investigate whether TPP1 promoter mutations cooperate with TERT promoter mutations in melanoma. | U. Pittsburgh & UC Santa Cruz, USA. | 749 melanoma samples. | Genomic and functional analysis. | TPP1 promoter variants co-occur with TERT mutations, enhancing TPP1 expression and synergistically lengthening telomeres in melanoma cells. |

| Noureen [15] | To quantify telomerase enzymatic activity and explore its link with cancer stemness and proliferation. | UT Health San Antonio & MD Anderson Cancer Center, USA. | >9000 tumors from TCGA and multiple validation cell lines. | Computational and experimental validation study. | Developed the EXTEND algorithm; showed telomerase activity strongly correlates with cancer stemness and proliferation, outperforming TERT expression as a biomarker. |

| TERT Alteration | Type of Alteration | Effect on TERT Expression/Activity | Cellular Phenotype Associated | Relationship with TERT Promoter Mutation | Potential Impact on Anti-TERT Therapies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C228T promoter mutation | Promoter mutation (ETS binding site creation) | ↑ Increased TERT transcription and telomerase activity | Enhanced proliferation, replicative immortality, tumor progression | Independent or coexists with promoter methylation | Likely increased dependence on telomerase; potential better target for anti-TERT therapy |

| C250T promoter mutation | Promoter mutation (ETS binding site creation) | ↑ Increased TERT transcription and telomerase activity | Increased tumor growth, invasion, poor prognosis | May coexist with THOR hypermethylation | May respond to telomerase-directed therapies (vaccines/inhibitors) |

| TERT promoter hypermethylation (THOR) | Epigenetic modification | ↑ Upregulation of TERT despite hypermethylation | Telomerase reactivation and melanoma progression | Can occur with or without promoter mutations | Supports rationale for anti-TERT therapy; predictive value still under investigation |

| TERT gene amplification | Copy number gain | ↑ Increased TERT expression due to higher gene dosage | Increased telomerase activity; aggressive biology | Independent of promoter mutations | Suggests strong telomerase dependence → potential sensitivity |

| Structural variants near TERT | Rearrangements | ↑ Increased enhancer–promoter interactions | Telomerase activation and tumor progression | Sometimes independent of promoter mutation | Mechanism-specific response unknown; still investigational |

| Wild-type TERT promoter with low methylation | No mutation; no THOR methylation | → Low or baseline activity | Reduced telomerase dependence | None | May show less benefit from anti-TERT-directed therapy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alqaisi, O.; Storme, G.; Dennis, A.; Dibas, M.; Sijarina, L.; Grabovci, L.; Al-Zghoul, S.; Yu, E.; Tai, P. Telomerase Activity in Melanoma: Impact on Cancer Cell Proliferation Kinetics, Tumor Progression, and Clinical Therapeutic Strategies—A Scoping Review. Curr. Oncol. 2026, 33, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020074

Alqaisi O, Storme G, Dennis A, Dibas M, Sijarina L, Grabovci L, Al-Zghoul S, Yu E, Tai P. Telomerase Activity in Melanoma: Impact on Cancer Cell Proliferation Kinetics, Tumor Progression, and Clinical Therapeutic Strategies—A Scoping Review. Current Oncology. 2026; 33(2):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020074

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlqaisi, Omar, Guy Storme, Amaechi Dennis, Mohammed Dibas, Lorent Sijarina, Liburn Grabovci, Shima Al-Zghoul, Edward Yu, and Patricia Tai. 2026. "Telomerase Activity in Melanoma: Impact on Cancer Cell Proliferation Kinetics, Tumor Progression, and Clinical Therapeutic Strategies—A Scoping Review" Current Oncology 33, no. 2: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020074

APA StyleAlqaisi, O., Storme, G., Dennis, A., Dibas, M., Sijarina, L., Grabovci, L., Al-Zghoul, S., Yu, E., & Tai, P. (2026). Telomerase Activity in Melanoma: Impact on Cancer Cell Proliferation Kinetics, Tumor Progression, and Clinical Therapeutic Strategies—A Scoping Review. Current Oncology, 33(2), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020074