“The Day He Fell Ill, We Turned on a Switch…Now, Everything Is My Responsibility”: Scoping Review of Qualitative Studies Among Partners of Patients with Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

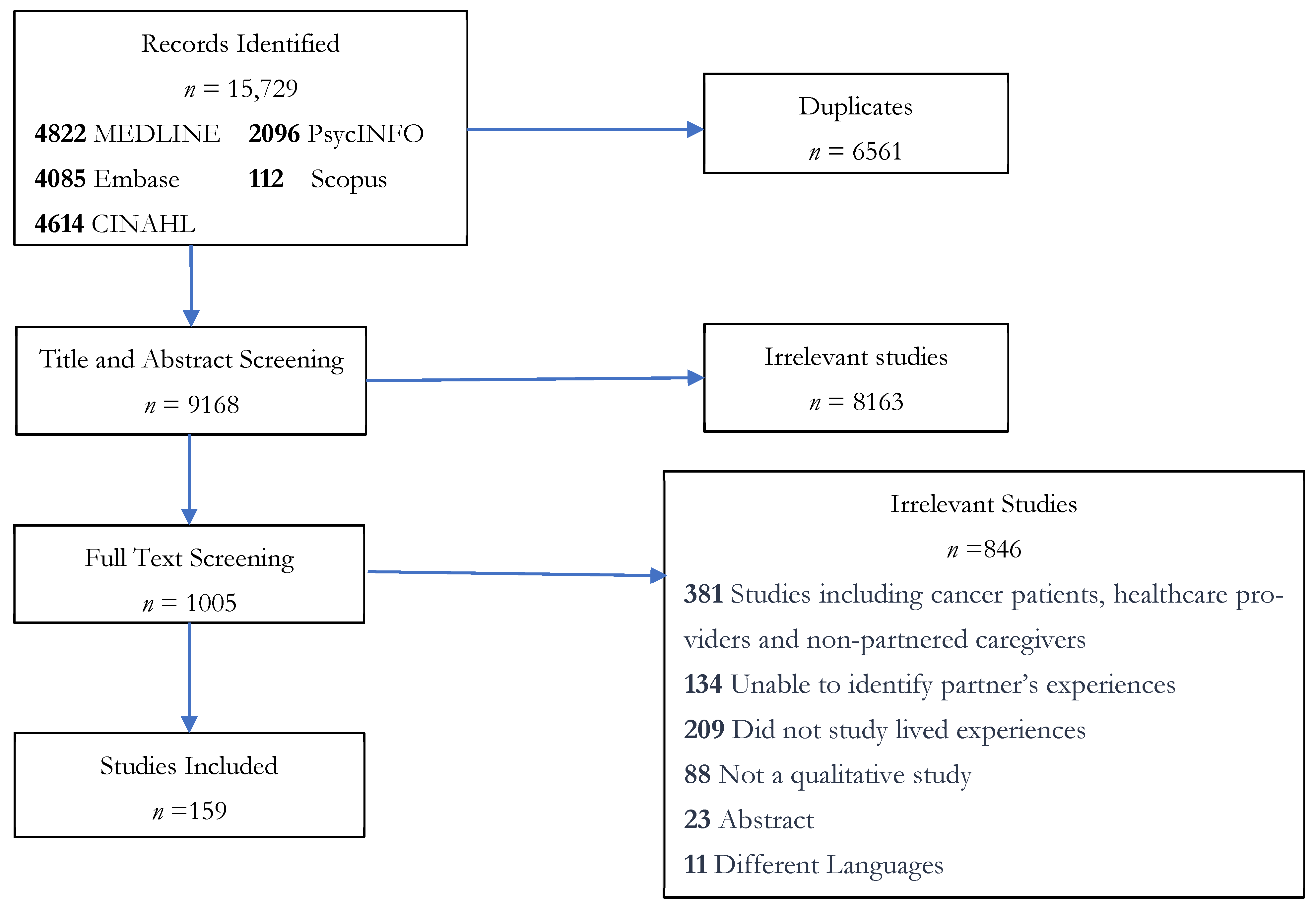

2.2. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

3.2. Partner Participants

3.3. Narrative Summary

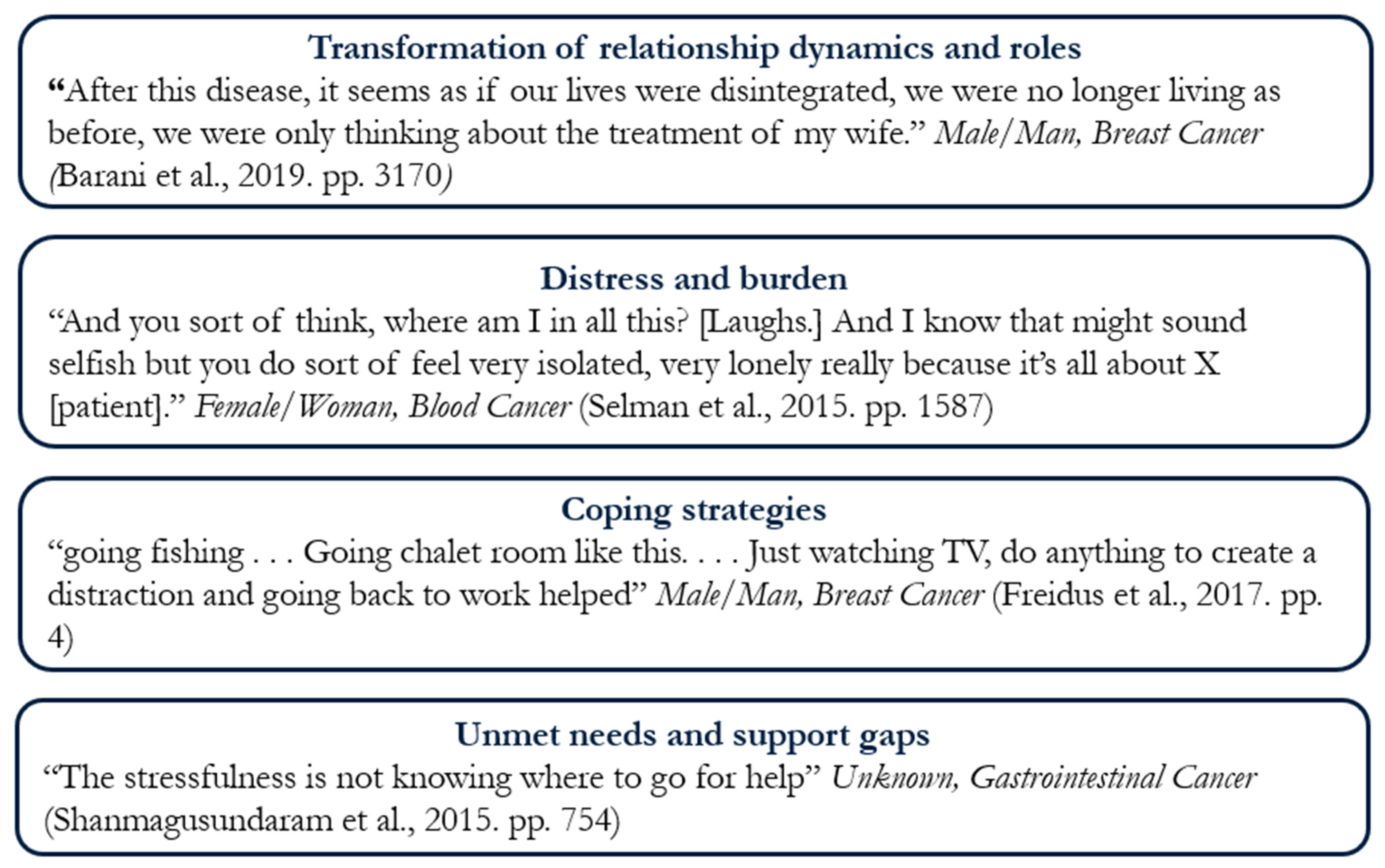

3.4. Transformation of Relationship Dynamics and Roles

3.5. Distress and Burden

3.6. Coping Strategies

3.7. Unmet Needs and System Gaps

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santucci, C.; Carioli, G.; Bertuccio, P.; Malvezzi, M.; Pastorino, U.; Boffetta, P.; Negri, E.; Bosetti, C.; Vecchia, C. Progress in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival: A global overview. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 29, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, K.D.; Syrjala, K.L.; Andrykowski, M.A. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer 2008, 112, 2577–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshields, T.L.; Rihanek, A.; Potter, P.; Zhang, Q.; Kuhrik, M.; Kuhrik, N.; O’Neill, J. Psychosocial aspects of caregiving: Perceptions of cancer patients and family caregivers. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Gao, Y.; Huai, Q.; Du, Z.; Yang, L. Experiences of financial toxicity among caregivers of cancer patients: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, K.; Watson, L.E.; Andrade, J.T. Cancer as a “we-disease”: Examining the process of coping from a relational perspective. Fam. Syst. Health 2007, 25, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizer, A.A.; Chen, M.-H.; McCarthy, E.P.; Mendu, M.L.; Koo, S.; Wilhite, T.J.; Graham, P.L.; Choueiri, T.K.; Hoffman, K.E.; Martin, N.E.; et al. Marital Status and Survival in Patients With Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 3869–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajc, K.; Miroševič, Š.; Sajovic, J.; Klemenc Ketiš, Z.; Spiegel, D.; Drevenšek, G.; Drevenšek, M. Marital status and survival in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 1685–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, A.C.; Yi, J.; Wright, J.; Warner, E.L.; Smith, K.R. Marriage and divorce among young adult cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2012, 6, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rha, S.Y.; Park, Y.; Song, S.K.; Lee, C.E.; Lee, J. Caregiving burden and the quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients: The relationship and correlates. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesley, V.L.; Price, M.A.; Webb, P.M.; Australian Ovarian Cancer Study, G.; Australian Ovarian Cancer Study-Quality of Life Study, I. Loss of lifestyle: Health behaviour and weight changes after becoming a caregiver of a family member diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2011, 19, 1949–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Shaffer, K.M.; Carver, C.S.; Cannady, R.S. Prevalence and predictors of depressive symptoms among cancer caregivers 5 years after the relative’s cancer diagnosis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.D.; Harrison, J.D.; Smith, E.; Bonevski, B.; Carey, M.; Lawsin, C.; Paul, C.; Girgis, A. The unmet needs of partners and caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer: A systematic review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2012, 2, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, C.Y.; Buchanan Lunsford, N.; Lee Smith, J. Impact of informal cancer caregiving across the cancer experience: A systematic literature review of quality of life. Palliat. Support. Care 2020, 18, 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, N.I.; Nielsen, C.I.; Danbjorg, D.B.; Moller, P.K.; Brochstedt Dieperink, K. Caregivers’ Need for Support in an Outpatient Cancer Setting. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2019, 46, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, H.; Webb, K.; Sharpe, L.; Shaw, J. A qualitative exploration of fear of cancer recurrence in caregivers. Psycho-Oncology 2023, 32, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, J.M.; Tim Wong, W.K.; Perz, J. A qualitative analysis of changes in relationship dynamics and roles between people with cancer and their primary informal carer. Health 2011, 15, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boylorn, R.M. Lived Experiences. In The Qualitative Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Colquhoun, H.; Garritty, C.M.; Hempel, S.; Horsley, T.; Langlois, E.V.; Lillie, E.; O’Brien, K.K.; Tuncalp, O.; et al. Scoping reviews: Reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrea, C.; Tricco, E.L.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhuon, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Reblin, M.; Uchino, B.N. Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2008, 21, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation M: Melbourne, Australia.

- Clarke, J.A. Sex assigned at birth. Columbia Law Rev. 2022, 122, 1821–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. In ESRC Methods Programme Version 11; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods, M.; Agarwal, S.; Jones, D.; Young, B.; Sutton, A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVivo, Version 14; Lumivero: Denver, CO, USA, 2024.

- Younes Barani, Z.; Rahnama, M.; Naderifar, M.; Badakhsh, M.; Noorisanchooli, H. Experiences of Spouses of Women with Breast Cancer: A Content Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2019, 20, 3167–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selman, L.E.; Beynon, T.; Radcliffe, E.; Whittaker, S.; Orlowska, D.; Child, F.; Harding, R. ‘We’re all carrying a burden that we’re not sharing’: A qualitative study of the impact of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma on the family. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 172, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freidus, R.A. Experiences of men who commit to romantic relationships with younger breast cancer survivors: A qualitative study. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2017, 35, 494–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, S. Unmet Needs of the Indian Family Members of Terminally Ill Patients Receiving Palliative Care Services. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2015, 17, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, S.; Dengso, K.E.; Herling, S.; Thomsen, T. From bystander to enlisted carer—A qualitative study of the experiences of caregivers of patients attending follow-up after curative treatment for cancers in the pancreas, duodenum and bile duct. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 44, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConigley, R.; Halkett, G.; Lobb, E.; Nowak, A. Caring for someone with high-grade glioma: A time of rapid change for caregivers. Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez, G.; Branin, J.J.; Rosales, M. The cancer caregiving experience of caregivers of Mexican ancestry. Hisp. Health Care Int. 2014, 12, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, E.; van Toorn, G.; Lwin, Z. Routines of isolation? A qualitative study of informal caregiving in the context of glioma in Australia. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 1924–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piolli, K.C.; Decesaro, M.D.N.; Sales, C.A. (Not) taking care of yourself as a woman while being a caregiver of a partner with cancer. Rev. Gaucha Enferm. 2018, 39, e2016–e2069. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda, S.; Peerson, A. Caregiving in advanced cancer: Lay decision making. J. Palliat. Care 2001, 17, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppetti, L.d.C.; Nietsche, E.A.; Schimith, M.D.; Radovanovic, C.A.T.; Lacerda, M.R.; Girardon-Perlini, N.M.O. Men’s experience of caring for a family member with cancer: A theory based on data. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2024, 32, e4095. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, S.R.; Hall, E.O.; Delmar, C. Ethical dilemmas experienced by spouses of a partner with brain tumour. Nurs. Ethics 2020, 27, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, L.O.; Friis, L.S.; Hansen, D.G.; Marcher, C.W.; Hoybye, M.T. Living with outpatient management as spouse to intensively treated acute leukemia patients. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, S.; Arber, A.; Trojan, A.; Faithfull, S. Caring for a loved one with a malignant fungating wound. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 3065–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halkett, G.K.; Golding, R.M.; Langbecker, D.; White, R.; Jackson, M.; Kernutt, E.; O’Connor, M. From the carer’s mouth: A phenomenological exploration of carer experiences with head and neck cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2020, 29, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coolbrandt, A.; Sterckx, W.; Clement, P.; Borgenon, S.; Decruyenaere, M.; de Vleeschouwer, S.; Mees, A.; de Casterle, B.D. Family Caregivers of Patients With a High-Grade Glioma: A Qualitative Study of Their Lived Experience and Needs Related to Professional Care. Cancer Nurs. 2015, 38, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wootten, A.C.; Abbott, J.M.; Osborne, D.; Austin, D.W.; Klein, B.; Costello, A.J.; Murphy, D.G. The impact of prostate cancer on partners: A qualitative exploration. Psychooncology 2014, 23, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahlis, E.H.; Lewis, F.M. Coming to grips with breast cancer: The spouse’s experience with his wife’s first six months. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2010, 28, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, B.; Balla, M.; Dutton, L.; Lewis, J.; Burns, R.; Gallagher, P.; Williams, S.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Finch, T.; Sharp, L. ‘A Constant Black Cloud’: The Emotional Impact of Informal Caregiving for Someone With a Lower-Grade Glioma. Qual. Health Res. 2024, 34, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrod, J.; Hupcey, J.E.; Baney, B.L.; Loeb, S.J. End-of-life caregiving trajectories. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2011, 20, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiatt, J.; Young, A.; Brown, T.; Banks, M.; Segon, B.; Bauer, J. A qualitative comparison of the nutrition care experiences of carers supporting patients with head and neck cancer throughout surgery and radiation treatment and survivorship. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 9359–9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.E. A time-sovereignty approach to understanding carers of cancer patients’ experiences and support preferences. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2014, 23, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, P.; Zegers, A.D.; de Vreeze, N.; van der Beek, A.J.; Duijts, S.F.A. ‘Nobody can take the stress away from me’: A qualitative study on experiences of partners of patients with cancer regarding their work and health. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 1696–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanberg, J.E. Making it work: Informal caregiving, cancer, and employment. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2006, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balfe, M.; Butow, P.; O’Sullivan, E.; Gooberman-Hill, R.; Timmons, A.; Sharp, L. The financial impact of head and neck cancer caregiving: A qualitative study. Psycho-Oncology 2016, 25, 1441–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owoo, B.; Ninnoni, J.P.; Ampofo, E.A.; Seidu, A.A. Challenges encountered by family caregivers of prostate cancer patients in Cape Coast, Ghana: A descriptive phenomenological study. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, E.; Ussher, J.M.; Hawkins, Y. Accounts of disruptions to sexuality following cancer: The perspective of informal carers who are partners of a person with cancer. Health 2009, 13, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, E.; Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J. Renegotiating Sexuality and Intimacy in the Context of Cancer: The Experiences of Carers. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2008, 27, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahlis, E.H.; Shands, M.E. The impact of breast cancer on the partner 18 months after diagnosis. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 1993, 9, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, A.; Taleghani, F.; Irajpour, A. Men’s sexual issues after breast cancer in their wives: A qualitative study. Cancer Nurs. 2012, 35, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringborg, C.H.; Wengstrom, Y.; Schandl, A.; Lagergren, P. The long-term experience of being a family caregiver of patients surgically treated for oesophageal cancer. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 2259–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, R.M.; Tlusty, G.; Tanis, K.; Lake, K.; Jobanputra, J.; Cozad, M. Experiences of care partners co-surviving in the context of living with metastatic breast cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2025, 43, 736–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.; Snowden, A.; Kyle, R.G.; Stenhouse, R. Men’s perspectives of caring for a female partner with cancer: A longitudinal narrative study. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e5346–e5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, R.E. Indefinite loss: The experiences of carers of a spouse with cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2014, 23, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, K.; Sharpe, L.; Russell, H.; Shaw, J. Fear of cancer recurrence in ovarian cancer caregivers: A qualitative study. Psychooncology 2024, 33, e6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbutiene, E.; Pukinskaite, R. Fear of Cancer Recurrence as Reminder About Death: Lived Experiences of Cancer Survivors’ Spouses. Omega 2025, 90, 1381–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, K.M.; Weeks, M.; Spronk, K.J.J.; Fletcher, C.; Wilson, C. Caring for someone with cancer in rural Australia. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4857–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, L.M.; Allan, D.E.; Stajduhar, K.I. Palliative family caregivers’ accounts of health care experiences: The importance of “security”. Palliat. Support. Care 2009, 7, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabler, J.; Utz, R.L.; Ellington, L.; Reblin, M.; Caserta, M.; Clayton, M.; Lund, D. Missed Opportunity: Hospice Care and the Family. J. Soc. Work. End Life Palliat. Care 2015, 11, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbozi, P.; Mukwato, P.K.; Kalusopa, V.M.; Simoonga, C. Experiences and coping strategies of women caring for their husbands with cancer at the Cancer Diseases Hospital in Lusaka, Zambia: A descriptive phenomenological approach. Ecancermedicalscience 2023, 17, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piil, K.; Juhler, M.; Jakobsen, J.; Jarden, M. Daily Life Experiences of Patients With a High-Grade Glioma and Their Caregivers: A Longitudinal Exploration of Rehabilitation and Supportive Care Needs. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2015, 47, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dri, E.; Bressan, V.; Cadorin, L.; Stevanin, S.; Bulfone, G.; Rizzuto, A.; Luca, G. Providing care to a family member affected by head and neck cancer: A phenomenological study. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 2105–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, M.K.; Birkelund, R.; Mortensen, M.B.; Schultz, H. Undertaking responsibility and a new role as a relative: A qualitative focus group interview study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 35, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun, P.; Pedersen, B.D.; Osther, P.J.; Wagner, L. The lonely female partner: A central aspect of prostate cancer. Urol. Nurs. 2011, 31, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinks, D.; Davis, C.; Pinks, C. Experiences of partners of prostate cancer survivors: A qualitative study. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2018, 36, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquati, C.; Head, K.J.; Rand, K.L.; Alwine, J.S.; Short, D.N.; Cohee, A.A.; Champion, V.L.; Draucker, C.B. Psychosocial Experiences, Challenges, and Recommendations for Care Delivery among Partners of Breast Cancer Survivors: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, E.O.; Oti-Boadi, E.; Amertil, N.P.; Afotey, R.; Lavoe, H.; Garti, I.; Menlah, A.; Sekyi, E.K.N. Journeying together: Spousal experiences with prostate cancer in Ghana. Ecancermedicalscience 2024, 18, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traboulssi, M.; Pidgeon, M.; Weathers, E. My Wife Has Breast Cancer: The Lived Experience of Arab Men. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 38, 151307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M.A.; Hoppe, R.; Albrecht, T.A. “I don’t have a choice but to keep getting up and doing the things that protect her”: The informal caregiver’s adaptation to the cancer diagnosis. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2024, 42, 622–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, P. Caregivers’ insights on the dying trajectory in hematology oncology. Cancer Nurs. 2001, 24, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, M.I.; Allard, M. Perspectives of husbands of women with breast cancer: Impact and response. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2007, 17, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gara, G.; Wiseman, T.; Doyle, A.-M.; Pattison, N. Chronic illness and critical care-A qualitative exploration of family experience and need. Nurs. Crit. Care 2023, 28, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah Mensah, A.B.; Adamu, B.; Mensah, K.B.; Dzomeku, V.M.; Agbadi, P.; Kusi, G.; Apiribu, F. Exploring the social stressors and resources of husbands of women diagnosed with advanced breast cancer in their role as primary caregivers in Kumasi, Ghana. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2335–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonidou, C.; Giannousi, Z. Experiences of caregivers of patients with metastatic cancer: What can we learn from them to better support them? Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 32, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germeni, E.; Sarris, M. Experiences of cancer caregiving in socioeconomically deprived areas of Attica, Greece. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ussher, J.M.; Sandoval, M.; Perz, J.; Wong, W.K.; Butow, P. The gendered construction and experience of difficulties and rewards in cancer care. Qual. Health Res. 2013, 23, 900–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, E.Y.N.; Toke, S.; Macpherson, H.; Wilson, C. Factors which influence social connection among cancer caregivers: An exploratory, interview study. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannarino, N.T. ‘It’s my job now, I guess’: Biographical disruption and communication work in supporters of young adult cancer survivors. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 491–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Raman, M.; Walpola, R.L.; Chauhan, A.; Sansom-Daly, U.M. Preparing for partnerships in cancer care: An explorative analysis of the role of family-based caregivers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Jackman, M.; McQuestion, M.; Fitch, M.I. Coping style and typology of perceived social support of male partners of women with breast cancer. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J./Rev. Can. Nurs. Oncol. 2022, 32, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roen, I.; Stifoss-Hanssen, H.; Grande, G.; Brenne, A.T.; Kaasa, S.; Sand, K.; Knudsen, A.K. Resilience for family carers of advanced cancer patients-how can health care providers contribute? A qualitative interview study with carers. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C.R.; Johnson-Koenke, R.; Sousa, K.H. I-Poems: A Window Into the Personal Experiences of Family Caregivers of People Living With Advanced Cancer. Nurs. Res. 2024, 73, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.S. ‘I was trapped at home’: Men’s experiences with leisure while giving care to partners during a breast cancer experience. Leis. Sci. 2015, 37, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, V.; Copp, G.; Molassiotis, A. Male caregivers of patients with breast and gynecologic cancer: Experiences from caring for their spouses and partners. Cancer Nurs. 2012, 35, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noveiri, M.J.S.; Shamsaei, F.; Khodaveisi, M.; Vanaki, Z.; Tapak, L. The concept of coping in male spouses of Iranian women with breast cancer: A qualitative study using a phenomenological approach. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. Rev. Can. Nurs. Oncol. 2021, 31, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostrøm, V.; Sørlie, V. Gender differences in experiences in partners of patients diagnosed with cancer. Nord. J. Nurs. Res. Clin. Stud./Vård I Nord. 2003, 23, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bamidele, O.; Lagan, B.M.; McGarvey, H.; Wittmann, D.; McCaughan, E. “… It might not have occurred to my husband that this woman, his wife who is taking care of him has some emotional needs as well …”: The unheard voices of partners of Black African and Black Caribbean men with prostate cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Does, J.V.S.; Duyvis, D.J. Psychosocial adjustment of spouses of cervical carcinoma patients. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1989, 10, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The supportive care needs of family members of men with advanced prostate cancer. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J./Rev. Can. De Nurs. Oncol. 2010, 20, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, D.; Barden, S.M.; Gonzalez, J.; Ali, S.; Cruz-Ortega, L.G. Perspectiva masculina: An exploration of intimate partners of Latina breast cancer survivors. Fam. J. 2016, 24, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier-Beillard, N.; Ponthier, N.; Lepage, C.; Gagnaire, A.; Gheringuelli, F.; Bengrine, L.; Boudrant, A.; Rambach, L.; Quipourt, V.; Devilliers, H.; et al. Identification of resources and skills developed by partners of patients with advanced colon cancer: A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 4121–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.J.; Badger, T.A.; Segrin, C.; Thomson, C.A. Loneliness, Spirituality, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Hispanic English-Speaking Cancer Caregivers: A Qualitative Approach. J. Relig. Health 2024, 63, 1433–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lion, K.M.; Jamieson, A.; Billin, A.; Jones, S.; Pinkham, M.B.; Ownsworth, T. ‘It was never about me’: A qualitative inquiry into the experiences of psychological support and perceived support needs of family caregivers of people with high-grade glioma. Palliat. Med. 2024, 38, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.A.; Collins, K.E.; Vicario, J.N.; Sibthorpe, C.; Goodwin, B.C. “I’m not the one with cancer but it’s affecting me just as much”: A qualitative study of rural caregivers’ experiences seeking and accessing support for their health and wellbeing while caring for someone with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anthias, L. Constructing Personal and Couple Narratives in Late-stage Cancer: Can a Typology Illuminate the Caring Partner Perspective? Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 2016, 37, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ka’opua, L.S.I.; Gotay, C.C.; Hannum, M.; Bunghanoy, G. Adaptation to long-term prostate cancer survival: The perspective of elderly Asian/Pacific Islander wives. Health Soc. Work. 2005, 30, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusa, S.; Persson, C.; Sundin, K. Significant others’ lived experiences following a lung cancer trajectory: From diagnosis through and after the death of a family member. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 16, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmer, C.; Ward-Smith, P.; Latham, S.; Salacz, M. When a family member has a malignant brain tumor: The caregiver perspective. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2008, 40, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, A.F.; Couper, J.W.; Love, A.W.; Bloch, S.; Kissane, D.W.; Street, B.C. Psychosocial adaptation in female partners of men with prostate cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2010, 19, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, K.T.; Craig, K.W.; Parker Oliver, D.; Ruggeri, J.S.; Brunk, S.R.; Goldstein, A.K.; Demiris, G. Family caregivers’ perspectives on communication with cancer care providers. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2019, 37, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, K.T.; Benson, J.J.; Chakurian, D.E.; Popejoy, L.L.; Demiris, G.; Rolbiecki, A.J.; Oliver, D.P. Comfort Needs of Cancer Family Caregivers in Outpatient Palliative Care. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2021, 23, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komariyah, S.N.; Fitriana, F.; Lestari, P. Husbands’ perceptions and experiences in caring for wife with cervical cancer: A qualitative phenomenological study. Indones. Midwifery Health Sci. J. 2024, 8, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anngela-Cole, L.; Busch, M. Stress and grief among family caregivers of older adults with cancer: A multicultural comparison from Hawai’i. J. Soc. Work. End Life Palliat. Care 2011, 7, 318–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkel, I.; Wijk, H.; Molander, U. Loved Ones Obtain Various Information About the Progression of the Patient’s Cancer Disease Which is Important for Their Understanding and Preparation. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2012, 29, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, J.; Harrison, J.; Young, J.; Butow, P.; Sandroussi, C.; Martin, D.; Solomon, M. Coping with newly diagnosed upper gastrointestinal cancer: A longitudinal qualitative study of family caregivers’ role perception and supportive care needs. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervik, B.; Nord⊘y, T.; Asplund, K. In the Middle and on the Sideline. Cancer Nurs. 2013, 36, E7–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Fradgley, E.; Clinton-McHarg, T.; Byrnes, E.; Paul, C. What are the sources of distress in a range of cancer caregivers? A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2443–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemmer, S.J.; Ward-Griffin, C.; Forbes, D. Family members providing home-based palliative care to older adults: The enactment of multiple roles. Can. J. Aging 2008, 27, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlberg, M.; Wannheden, C.; Andersson, S.; Bylund, A. “Try to keep things going”—Use of various resources to balance between caregiving and other aspects of life: An interview study with informal caregivers of persons living with brain tumors in Sweden. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 74, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggleby, W.; Bally, J.; Cooper, D.; Doell, H.; Thomas, R. Engaging hope: The experiences of male spouses of women with breast cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2012, 39, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggleby, W.; Williams, A.; Holtslander, L.; Cunningham, S.; Wright, K. The chaos of caregiving and hope. Qual. Soc. Work. 2012, 11, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egestad, L.K.; Gyldenvang, H.H.; Jarden, M. “My Husband Has Breast Cancer”: A Qualitative Study of Experiences of Female Partners of Men With Breast Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2020, 43, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.; Cagle, C.S.; Bradley, P. ‘We are stronger than the cancer.’ The voices of Mexican American family caregivers of cancer patients. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2007, 34, 230. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, R.; O’Connor, M.; Golding, R.M.; Gibson, C.; White, R.; Jackson, M.; Langbecker, D.; Bosco, A.M.; Tan, M.; Halkett, G.K.B. “My life’s not my own”: A qualitative study into the expectations of head and neck cancer carers. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4073–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim, R.; Hales, S.; Zimmermann, C.; Deckert, A.; Edwards, B.; Rodin, G. Supporting family caregivers of advanced cancer patients: A focus group study. Fam. Relat. Interdiscip. J. Appl. Fam. Stud. 2017, 66, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roing, M.; Hirsch, J.M.; Holmstrom, I. Living in a state of suspension—A phenomenological approach to the spouse’s experience of oral cancer. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2008, 22, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.C.; Hicks, E.M.; Chang, N.; Connor, S.E.; Maliski, S.L. Purposeful normalization when caring for husbands recovering from prostate cancer. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.A.; Collins, K.E.; Vicario, J.N.; Sibthorpe, C.; Ireland, M.J.; Goodwin, B.C. Changes in rural caregivers’ health behaviors while supporting someone with cancer: A qualitative study. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, L.; Rosenkranz, S.J.; Wherity, K.; Sasaki, A. Living With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Near the End of Life: Family Caregivers’ Perspectives. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2017, 44, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajduhar, K.I.; Martin, W.L.; Barwich, D.; Fyles, G. Factors influencing family caregivers’ ability to cope with providing end-of-life cancer care at home. Cancer Nurs. 2008, 31, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranberg, M.; Andersson, M.; Nilbert, M.; Rasmussen, B.H. Co-afflicted but invisible: A qualitative study of perceptions among informal caregivers in cancer care. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 1850–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ownsworth, T.; Goadby, E.; Chambers, S.K. Support after brain tumor means different things: Family caregivers’ experiences of support and relationship changes. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolucci, A.; Nielssen, I.; Tang, K.L.; Sinnarajah, A.; Simon, J.E.; Santana, M.J. The impacts of partnering with cancer patients in palliative care research: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2022, 16, 26323524221131581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year of Publication | No. of Studies (%) |

| 1986–1990 | 2 (1.3%) |

| 1991–1995 | 1 (0.6%) |

| 1996–2000 | 1 (0.6%) |

| 2001–2005 | 5 (3.1%) |

| 2006–2010 | 19 (11.9%) |

| 2011–2015 | 40 (25.2%) |

| 2016–2020 | 32 (20.1%) |

| 2021–2025 | 59 (37.1%) |

| Place of Publication | No. of Studies (%) |

| Europe | 49 (30.8%) |

| North America | 44 (27.7%) |

| Australia | 36 (22.6%) |

| Asia | 19 (11.9%) |

| Africa | 10 (6.3%) |

| South America | 1 (0.6%) |

| Terminology Used | No. of Studies (%) |

| Caregiver/Carer | 75 (47.2%) |

| Spouse/Partner/Husband/Wife | 71 (44.7%) |

| Family/Family Members | 8 (5%) |

| Other (e.g., Next of Kin) | 4 (2.5%) |

| Loved One | 1 (0.6%) |

| Methodology 1 | No. of Studies (%) |

| Thematic Analysis | 43 (27%) |

| Content Analysis | 32 (20.1%) |

| Grounded Theory | 24 (15.1%) |

| Mixed | 22 (13.8%) |

| Phenomenological Approaches | 21 (13.2%) |

| Other | 10 (6.3%) |

| Narrative-/Framework-based | 4 (2.5%) |

| Interpretive Description | 3 (1.9%) |

| Qualitative Data Collection Method Used | No. of Studies (%) |

| Interviews | 147 (92.5%) |

| Focus Groups | 8 (5%) |

| Focus Groups and Interviews | 4 (2.5%) |

| Participant Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Total Participants | 3042 |

| Sex 1 | No. of Participants (%) |

| Female | 1780 (59.2%) |

| Male | 1229 (40.8%) |

| Age | Age (yrs) |

| Mean Age | 55.2 ± 8.3 years 2 |

| Age Range | 18–80+ 3 |

| Cancer Type | No. of Participants (%) |

|---|---|

| Unspecified/Other | 715 (23.5%) |

| Breast | 613 (20.1%) |

| Genitourinary (Including Prostate) | 386 (12.7%) |

| Gastrointestinal (Including Colorectal) | 285 (9.4%) |

| Neuro-oncology (Central Nervous System) | 246 (8.1%) |

| Thoracic | 207 (6.8%) |

| Head and Neck | 212 (7%) |

| Gynecological | 184 (6%) |

| Hematologic/Immune | 138 (4.5%) |

| Neuroendocrine Tumour (NET) | 24 (0.8%) |

| Skin | 24 (0.8%) |

| Sarcoma/Bone and Soft Tissue | 8 (0.3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kang, P.; Ellis, U.; Cragg, J.J.; Howard, A.F.; Srikanthan, A.; Oveisi, N.; De Vera, M.A. “The Day He Fell Ill, We Turned on a Switch…Now, Everything Is My Responsibility”: Scoping Review of Qualitative Studies Among Partners of Patients with Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2026, 33, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020069

Kang P, Ellis U, Cragg JJ, Howard AF, Srikanthan A, Oveisi N, De Vera MA. “The Day He Fell Ill, We Turned on a Switch…Now, Everything Is My Responsibility”: Scoping Review of Qualitative Studies Among Partners of Patients with Cancer. Current Oncology. 2026; 33(2):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020069

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Preet, Ursula Ellis, Jacquelyn J. Cragg, A. Fuchsia Howard, Amirrtha Srikanthan, Niki Oveisi, and Mary A. De Vera. 2026. "“The Day He Fell Ill, We Turned on a Switch…Now, Everything Is My Responsibility”: Scoping Review of Qualitative Studies Among Partners of Patients with Cancer" Current Oncology 33, no. 2: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020069

APA StyleKang, P., Ellis, U., Cragg, J. J., Howard, A. F., Srikanthan, A., Oveisi, N., & De Vera, M. A. (2026). “The Day He Fell Ill, We Turned on a Switch…Now, Everything Is My Responsibility”: Scoping Review of Qualitative Studies Among Partners of Patients with Cancer. Current Oncology, 33(2), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020069