An Environmental Scan of Services for Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer Across Canadian Pediatric and Adult Tertiary Care Centres

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cancer Centre Identification

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondent Demographics

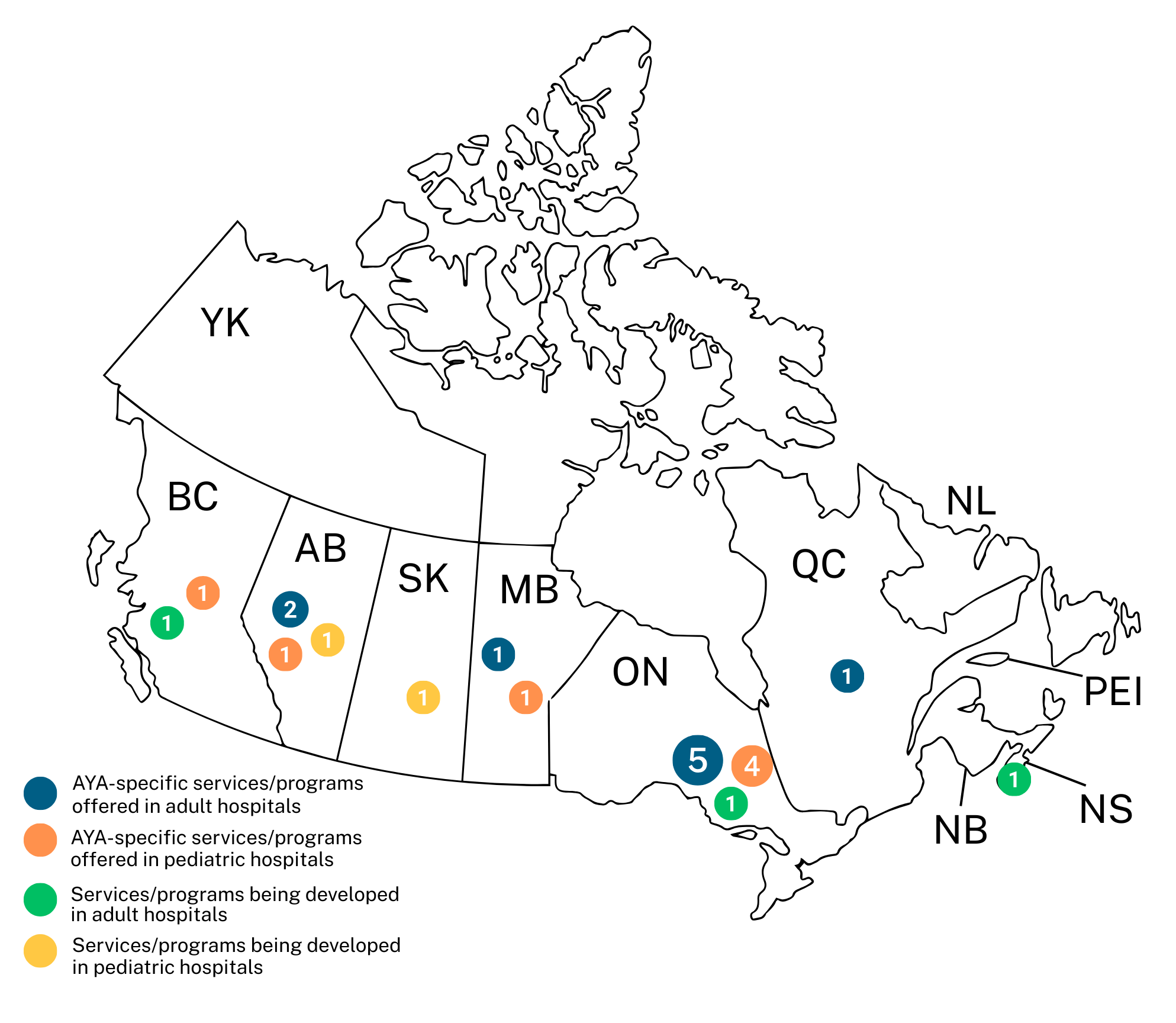

3.2. Available AYA Services and Programs

3.3. Institutional Age Limits for AYA Programming

3.4. Available Programs and Services for AYAs

3.5. Collaboration Between Pediatric and Adult Centres and Specialized Staff

3.6. Communication with AYA Patients

3.7. Funding for AYA Services and Programs

3.8. AYA-Specific Space

3.9. Accessing Clinical Trials for AYAs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AYA | Adolescent and Young Adults |

References

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2023; Canadian Cancer Society: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs)—Cancer Stat Facts. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/aya.html (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Janssen, S.H.M.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; van der Meer, D.J.; Manten-Horst, E.; Husson, O. Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Survivorship Practices: An Overview. Cancers 2021, 13, 4847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, R.D.; Ferrari, A.; Ries, L.; Whelan, J.; Bleyer, W.A. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Narrative Review of the Current Status and a View of the Future. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleyer, A. Latest Estimates of Survival Rates of the 24 Most Common Cancers in Adolescent and Young Adult Americans. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2011, 1, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleyer, A.; Barr, R.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Thomas, D.; Ellis, C.; Anderson, B.; on behalf of the Biology and Clinical Trials Subgroups of the US National Cancer Institute Progress Review Group in Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. The Distinctive Biology of Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siembida, E.J.; Loomans-Kropp, H.A.; Trivedi, N.; O’Mara, A.; Sung, L.; Tami-Maury, I.; Freyer, D.R.; Roth, M. Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators to Clinical Trial Enrollment among Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Identifying Opportunities for Intervention. Cancer 2020, 126, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, A.E.; Rae, C.; Fraser, G.A.; Meyer, R.M.; Abbott, L.S.; Bevan, S.; McBride, M.L.; Cuvelier, G.D.E.; McKillop, S.; Barr, R.D. Accrual of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer to Clinical Trials. Curr. Oncol. 2016, 23, e81–e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, F.S.M.; Chalifour, K.; Eaton, G.; Garland, S.N. Quality of Life among Survivors of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer in Canada: A Young Adults with Cancer in Their Prime (YACPRIME) Study. Cancer 2021, 127, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.; Tam, S.; Lewin, J.; Srikanthan, A.; Heck, C.; Hodgson, D.; Vakeesan, B.; Sim, H.-W.; Gupta, A. Measuring the Impact of an Adolescent and Young Adult Program on Addressing Patient Care Needs. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2018, 7, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, E.; Spunt, S.L.; Malogolowkin, M.; Li, Q.; Wun, T.; Brunson, A.; Thorpe, S.; Kreimer, S.; Keegan, T. Treatment at Specialized Cancer Centers Is Associated with Improved Survival in Adolescent and Young Adults with Soft Tissue Sarcoma. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2022, 11, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muffly, L.S.; Parsons, H.M.; Miller, K.; Li, Q.; Brunson, A.; Keegan, T.H. Impact of Specialized Treatment Setting on Survival in Adolescent and Young Adult ALL. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, J.; Ma, J.M.Z.; Mitchell, L.; Tam, S.; Puri, N.; Stephens, D.; Srikanthan, A.; Bedard, P.; Razak, A.; Crump, M.; et al. The Positive Effect of a Dedicated Adolescent and Young Adult Fertility Program on the Rates of Documentation of Therapy-Associated Infertility Risk and Fertility Preservation Options. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramphal, R.; D’Agostino, N.; Klassen, A.; McLeod, M.; De Pauw, S.; Gupta, A. Practices and Resources Devoted to the Care of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer in Canada: A Survey of Pediatric and Adult Cancer Treatment Centers. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2011, 1, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovsepyan, S.; Hoveyan, J.; Sargsyan, L.; Hakobyan, L.; Krmoyan, L.; Kamalyan, A.; Manukyan, N.; Atoyan, S.; Muradyan, A.; Danelyan, S.; et al. The Unique Challenges of AYA Cancer Care in Resource-Limited Settings. Front. Adolesc. Med. 2023, 1, 1279778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, M.P.; Roth, M.E.; Parsons, S.K. Reducing Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Outcome Disparities Through Optimized Care Delivery: A Blueprint from the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košir, U.; Totovina, A.; Stark, D.; Ferrari, A.; de Munter, J.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; Manten-Horst, E.; Rizvi, K. Minimum Standards of Specialist Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Care Units: Recommendations and Implementation Roadmap. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 105829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.; Allison, K.R.; Bibby, H.; Thompson, K.; Lewin, J.; Briggs, T.; Walker, R.; Osborn, M.; Plaster, M.; Hayward, A.; et al. The Australian Youth Cancer Service: Developing and Monitoring the Activity of Nationally Coordinated Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Care. Cancers 2021, 13, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePauw, S.; Rae, C.; Schacter, B.; Rogers, P.; Barr, R.D. Evolution of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology in Canada. Curr. Oncol. 2019, 26, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.; Fraser, G.A.M.; Freeman, C.; Grunfeld, E.; Gupta, A.; Mery, L.S.; De Pauw, S.; Schacter, B.; for the Canadian Task Force on Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Principles and Recommendations for the Provision of Healthcare in Canada to Adolescent and Young Adult–Aged Cancer Patients and Survivors. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2011, 1, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Canadian Framework for the Care and Support of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McKillop, S.; Henning, J.W.; Schulte, F.; Wales, A.; Surgeoner, B.; Cancer Care Alberta; Alberta Health Services. Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Clinical Practice Guideline; Alberta Health Services: Edmonton AB, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Srikanthan, A.; Karpinski, J.; Gupta, A. Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Oncology: A Credentialed Area of Focused Competence in Canada. Cancer Med. 2022, 12, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Business Case for Oncofertility Screening in the Cancer System; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Increasing Access to Oncofertility Services for Young People; 2024–25 Annual Report; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tutelman, P.R.; Thurston, C.; Rader, T.; Henry, B.; Ranger, T.; Abdelaal, M.; Blue, M.; Buckland, T.W.; Del Gobbo, S.; Dobson, L.; et al. Establishing the Top 10 Research Priorities for Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancer in Canada: A Protocol for a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 2874–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young Adult Cancer Canada. About—Young Adult Cancer Canada. Available online: https://youngadultcancer.ca/about/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Thurston, C.; Deleemans, J.M.; Gisser, J.; Piercell, E.; Ramasamy, V.; Tutelman, P.R. The Development and Impact of AYA Can—Canadian Cancer Advocacy: A Peer-Led Advocacy Organization for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer in Canada. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 2582–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, I.; Oberoi, S. Developing an Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program in a Medium-Sized Canadian Centre: Lessons Learned. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 2420–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.A.; Papadakos, J.K.; Jones, J.M.; Amin, L.; Chang, E.K.; Korenblum, C.; Mina, D.S.; McCabe, L.; Mitchell, L.; Giuliani, M.E. Reimagining Care for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Programs: Moving with the Times. Cancer 2016, 122, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London Health Sciences Centre. New Adolescent & Young Adult Oncology Program Launches at London Health Sciences Centre. 2025. Available online: https://www.lhsc.on.ca/news/new-adolescent-young-adult-oncology-program-launches-at-london-health-sciences-centre (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Jones, J.M.; Fitch, M.; Bongard, J.; Maganti, M.; Gupta, A.; D’Agostino, N.; Korenblum, C. The Needs and Experiences of Post-Treatment Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, T.F.; Pearson, T.G. Using Environmental Scans in Educational Needs Assessment. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 1998, 18, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, M.; Johnson, R.; Thompson, K.; Anazodo, A.; Albritton, K.; Ferrari, A.; Stark, D. Models of Care for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Programs. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fern, L.A.; Lewandowski, J.A.; Coxon, K.M.; Whelan, J.; National Cancer Research Institute Teenage and Young Adult Clinical Studies Group, UK. Available, Accessible, Aware, Appropriate, and Acceptable: A Strategy to Improve Participation of Teenagers and Young Adults in Cancer Trials. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e341–e350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CanTeen Australia. Australian Youth Cancer Framework for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer; CanTeen Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oveisi, N.; Cheng, V.; Taylor, D.; Bechthold, H.; Barnes, M.; Jansen, N.; McTaggart-Cowan, H.; Brotto, L.A.; Peacock, S.; Hanley, G.E.; et al. Meaningful Patient Engagement in Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Research: A Framework for Qualitative Studies. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 1689–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, S.; Noskoff, K.; Hayakawa, J.; Frediani, J. Empowering Adolescents and Young Adults to Support, Lead, and Thrive: Development and Validation of an AYA Oncology Child Life Program. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 47, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.; Lukosius, D.B.; Avery, J.; Santaguida, A.; Powis, M.; Papadakos, T.; Addario, V.; Lovas, M.; Kukreti, V.; Haase, K.; et al. A Web-Based Cancer Self-Management Program (I-Can Manage) Targeting Treatment Toxicities and Health Behaviors: Human-Centered Co-Design Approach and Cognitive Think-Aloud Usability Testing. JMIR Cancer 2023, 9, e44914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, E.; Asad, S.; Lux, L.; Gan, H.; Noskoff, K.; Kumar, B.; Roggenkamp, B.; Salsman, J.M.; Birken, S. Guidance to Support the Implementation of Specialized Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Care: A Qualitative Analysis of Cancer Programs. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2022, 18, e1513–e1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puzhko, S. Québec’s Emergency Room Overcrowding and Long Wait Times: Don’t Apply “Band-Aids”, Treat the Underlying Disease! McGill J. Med. 2017, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Kurup, S.; Devaraja, K.; Shanawaz, S.; Reynolds, L.; Ross, J.; Bezjak, A.; Gupta, A.A.; Kassam, A. Adapting an Adolescent and Young Adult Program Housed in a Quaternary Cancer Centre to a Regional Cancer Centre: Creating Equitable Access to Developmentally Tailored Support. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Province/Territory | Pediatric Centres (n = 16) | Adult Centres (n = 23) |

|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | BC Children’s Hospital | BC Cancer Agency |

| Alberta | Alberta Children’s Hospital Stollery Children’s Hospital | Arthur Child Comprehensive Cancer Centre (formerly Tom Baker Cancer Centre) The Cross Cancer Institute |

| Saskatchewan | Jim Pattison Children’s Hospital | Saskatoon Cancer Centre |

| Manitoba | CancerCare Manitoba | CancerCare Manitoba |

| Ontario | The Hospital for Sick Children Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario McMaster Children’s Hospital Children’s Hospital, London Health Sciences Centre Kingston Health Sciences Centre | Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Mount Sinai Hospital Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre The Ottawa Hospital Juravinski Cancer Centre Kingston Health Sciences Centre London Health Sciences Centre Health Sciences North |

| Quebec | CHU de Sherbrooke CHU Sainte-Justine CHU de Quebec-Université Laval Montreal Children’s Hospital | Le Centre intégré de cancérologie du CHUM Jewish General Hospital Le Centre intégré de cancérologie de Laval CHUQ—Hôtel-Dieu de Quebec Cedars Cancer Centre |

| Newfoundland | Janeway Children’s Health & Rehabilitation Centre | Dr. H. Bliss Murphy Cancer Centre |

| New Brunswick | None | Dr. Everett Chalmers Regional Hospital |

| Nova Scotia | IWK Health Centre | QEII Cancer Centre |

| PEI | None | PEI Cancer Treatment Centre |

| Yukon | None | Whitehorse General Hospital |

| Hospital | Key Informant | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult (N = 19) | Nurse | 6 (32) | |

| Manager | 5 (26) | ||

| Oncologist | 2 (11) | ||

| Nurse Practitioner | 1 (5) | ||

| Palliative Care Physician | 1 (5) | ||

| Physician Assistant | 1 (5) | ||

| Psychologist | 1 (5) | ||

| Researcher | 1 (5) | ||

| Social Worker | 1 (5) | ||

| Pediatric (N = 13) | Oncologist | 4 (31) | |

| Psychologist | 3 (23) | ||

| Manager | 2 (15) | ||

| Nurse | 2 (15) | ||

| Nurse Practitioner | 1 (8) | ||

| Social Worker | 1 (8) |

| Ramphal et al. 2011 [14] | Current Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AYA Resource, Service, or Programme | Pediatric (n = 16) | Adult (n = 25) | Pediatric (n = 13) | Adult (n = 19) |

| AYA-specific programs for school-related/work issues | 44% | 17% | 46% | 32% |

| AYA-specific service for fertility concerns | 25% | 17% | 54% | 47% |

| AYA resources for sexual health | 13% | 8% | 31% | 37% |

| AYA-specific palliative care resources | 13% | 17% | 46% | 21% |

| AYA inpatient space | 25% | 13% | 31% | 5% |

| Cross-appointed staff | 30% | 20% | 23% | 32% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rutkowski, N.; Beattie, S.; Schulte, F.; Thurston, C.; Boychuk, A.; de Guzman Wilding, M.; Korenblum, C.; Tutelman, P.R. An Environmental Scan of Services for Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer Across Canadian Pediatric and Adult Tertiary Care Centres. Curr. Oncol. 2026, 33, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020068

Rutkowski N, Beattie S, Schulte F, Thurston C, Boychuk A, de Guzman Wilding M, Korenblum C, Tutelman PR. An Environmental Scan of Services for Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer Across Canadian Pediatric and Adult Tertiary Care Centres. Current Oncology. 2026; 33(2):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020068

Chicago/Turabian StyleRutkowski, Nicole, Sara Beattie, Fiona Schulte, Chantale Thurston, April Boychuk, Marie de Guzman Wilding, Chana Korenblum, and Perri R. Tutelman. 2026. "An Environmental Scan of Services for Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer Across Canadian Pediatric and Adult Tertiary Care Centres" Current Oncology 33, no. 2: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020068

APA StyleRutkowski, N., Beattie, S., Schulte, F., Thurston, C., Boychuk, A., de Guzman Wilding, M., Korenblum, C., & Tutelman, P. R. (2026). An Environmental Scan of Services for Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer Across Canadian Pediatric and Adult Tertiary Care Centres. Current Oncology, 33(2), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33020068