Olanzapine Plus Triple Antiemetic Therapy for the Prevention of Platinum-Based Delayed-Phase Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: A Meta-Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.1.1. Search Strategy

2.1.2. Selection Criteria

- (1)

- Participants: patients were ≥18 years old who were diagnosed with cancer and naïve to chemotherapy;

- (2)

- Outcomes: complete response (CR, defined as no emesis and no use of rescue medication) in the overall (0 to 120 h), acute (0 to 24 h), and delayed (24 to 120 h) phases; the proportion of patients who have complete control and no nausea in the phases above;

- (3)

- Study design: experimental group (With olanzapine: olanzapine plus triple antiemetic therapy) versus control group (without olanzapine: triple antiemetic therapy);

- (4)

- Chemotherapy regimen: platinum-based.

2.2. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. PRISMA Guidelines

| Platinum Category | Study Design | Sample Sizes | Gender (n): M, F | Age (Years) | Efficacy Endpoint | Type of Cancer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Year | Olanzapine Dosage | Platinum- Based | Dosage | With OLN | Without OLN | With OLN | Without OLN | With OLN | Without OLN | With OLN | Without OLN | With OLN, Without OLN | |

| Hironobu Hashimoto 2020 [15] | 5 mg | Cisplatin | ≥70 mg/m2 <70 mg/m2 One course of treatment | OLN + APR/FOS + PALO + DEX | Placebo + APR/FOS + PALO + DEX | 354 | 351 | 237, 118 | 234, 117 | Median 65 | Median 66 | CR/CC/TC | Head and neck 33, 25 Lung 179, 183 Esophageal 75, 79 Gastric 20, 19 Gynecological 34, 34 Urological 3, 1 Other 11, 10 |

| Satoshi Koyama 2023 [16] | 5 mg/10 mg | Cisplatin | 100 mg/m2, One course of treatment | OLN + APR + PALO + DEX | APR + PALO + DEX | 31 | 78 | 25, 6 | 71, 7 | Mean 61.6 | Mean 64.2 | CR | Head and neck cancer 31, 78 |

| Jiali Gao 2022 [17] | 5 mg | Cisplatin | 25 mg/m2/d, 3 day | OLN + APR + TRO + DEX | APR + TRO + DEX | 59 | 61 | 32, 27 | 31, 30 | Mean 60.39 | Mean 58.11 | CR | Lung cancer 31, 31 Others 28, 30 |

| YuanyuanZhao 2022 [18] | 5 mg | Cisplatin | 3-day total dose ≥ 75 mg/m2 | OLN + FOS + OND + DEX | PAL + FOS + OND + DEX | 175 | 174 | 137, 38 | 134, 40 | Median 60 | Median 58 | CR/NN | Lung 126, 126 Head and neck 24, 21 Other 25, 27 |

| Masakazu Abe 2015 [19] | 5 mg | Cisplatin | <50 mg/m2 ≥50 mg/m2 | OLN + APR + PALO/GRA + DEX | APR + PALO/GRA + DEX | 50 | 50 | 0, 50 | 0, 50 | Mean 53 | Mean 53 | CR/CC/TC/NN/NV/NRT | Uterine cervical cancer 23, 23 Uterine corpus cancer 22, 22 Uterine carcinosarcoma 2, 2 Ovarian cancer 2, 2 Vaginal cancer 1 |

| Yan Zhang 2024 [20] | 5 mg | Cisplatin | 25 mg/m2/d, 3 day | OLN + FOS/APR + GRA/TRO + DEX | FOS/APR + GRA/TRO + DEX | 23 | 23 | 14, 9 | 15, 8 | Mean 57.5 | Mean 59 | CR | Lung cancer 13, 15 Other 10, 8 |

| Lulu Zhang 2025 [21] | 5 mg | Cisplatin | 20 mg/m2 /day, 5 day | OLN + APR + TRO + DEX | Placebo + APR + TRO + DEX | 77 | 77 | 77, 0 | 77, 0 | Median 28 | Median 28 | CR/NN/TC | Testicular tumor 65 Mediastinal tumor 8 Other 4 |

| Naoki Inui 2024 [22] | 5 mg | Carboplatin | AUC ≥ 5 mg/mL/min | OLN + PALO/GRA + APR + DEX | Placebo + APR + PALO/GRA + DEX | 175 | 180 | 139, 36 | 140, 40 | Median 72 | Median 72 | CR/CC/TC/NN | Lung adenocarcinoma 82, 95 Squamous cell lung carcinoma 33, 33 Small cell lung cancer 38, 33 Others 12, 19 |

| Vikas Ostwal 2024 [23] | 10 mg | Oxaliplatin, Carboplatin | Oxaliplatin not given; Carboplatin: AUC ≥ 5 mg/mL/min | OLN + PALO + APR + DEX | PALO + APR + DEX | 274 | 270 | 180/102 | 179/99 | Median 51 | Median 50 | CR/NN/NV | Colorectal 165, 159 Gastric or gastroesophageal 22, 22 Non-small cell lung carcinoma 26, 29 Biliary tract carcinoma 31, 30 Biliary tract carcinoma 24, 24 Others 12, 14 |

| Author/Year | Country | Olanzapine Dosage | Platinum Type | Cisplatin-Dosage | Study Design | Sample Sizes | Gender (n): M, F | Age (Years) | Efficacy Endpoint | Type of Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hiroko Minatogawa 2024 [24] | Japan | 5 mg | Cisplatin | ≥50 mg/m2 | OLN + PALO + NK1 + DEX | 139 | 95, 44 | Median age 63 | CR | Esophageal 56 Head and neck 32 Lung 25 Gastric 10 Others 16 |

| Hiroko Minatogawa 2024(2) [24] | Japan | 5 mg | Cisplatin | ≥50 mg/m2 | OLN + PALO + NK1 + DEX | 139 | 97, 42 | Median 64 | CR | Esophageal 53 Head and neck 37 Lung 28 Gastric 6 Others 15 |

| Hirotoshi Iihara 2020 [25] | Japan | 5 mg | Carboplatin | ≥4 mg/mL/min | OLN + APR + GRN + DEX | 57 | 0, 57 | Median58 | CR | Ovarian cancer 26 Cervical cancer 7 Endometrial cancer 21 Others 3 |

| Jun Wang 2022 [26] | China | 5 mg | Cisplatin | 100 mg/m2 | OLN + APRT + TRO + DEX | 75 | 58, 17 | Mean 46 | CR | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

| Jun Wang 2022(2) [26] | China | 10 mg | Cisplatin | 100 mg/m2 | OLN + APRT + TRO + DEX | 75 | 58, 17 | Mean 46 | CR | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

| Kazuhisa Nakashima 2017 [27] | Japan | 5 mg | Cisplatin | 75 mg/m2 | OLN + APR + PALO + DEX | 30 | 27, 3 | Median 64 | CR | Lung cancer 40 Others 64 |

| Kazuki Tanaka 2019 [28] | Japan | 5 mg | Carboplatin | ≥6 mg/mL/min | OLN + 5HT3 + APRT/FOS + DEX | 33 | 29, 4 | Median 75 | CR | Non-squamous NSCLC 33 |

| Masakazu Abe 2016 [29] | Japan | 5 mg | Cisplatin | ≥50 mg/m2 | OLN + APR + PALO + DEX | 40 | 0, 40 | Median 57 | CR | Cervical cancer 20 Endometrial cancer 19 Vulval cancer |

| Junichi Nishimura 2021 [30] | Japan | 5 mg | Oxaliplatin | 85 mg/m2 | OLN + APR + PALO + DEX | 40 | 23, 17 | Median 60 | CR | Colorectal cancer 40 |

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics and Quality

3.3. Complete Response and Other Efficacy Outcomes

3.3.1. Complete Response Rate

CR with Controlled Clinical Trial

CR of Single Arm

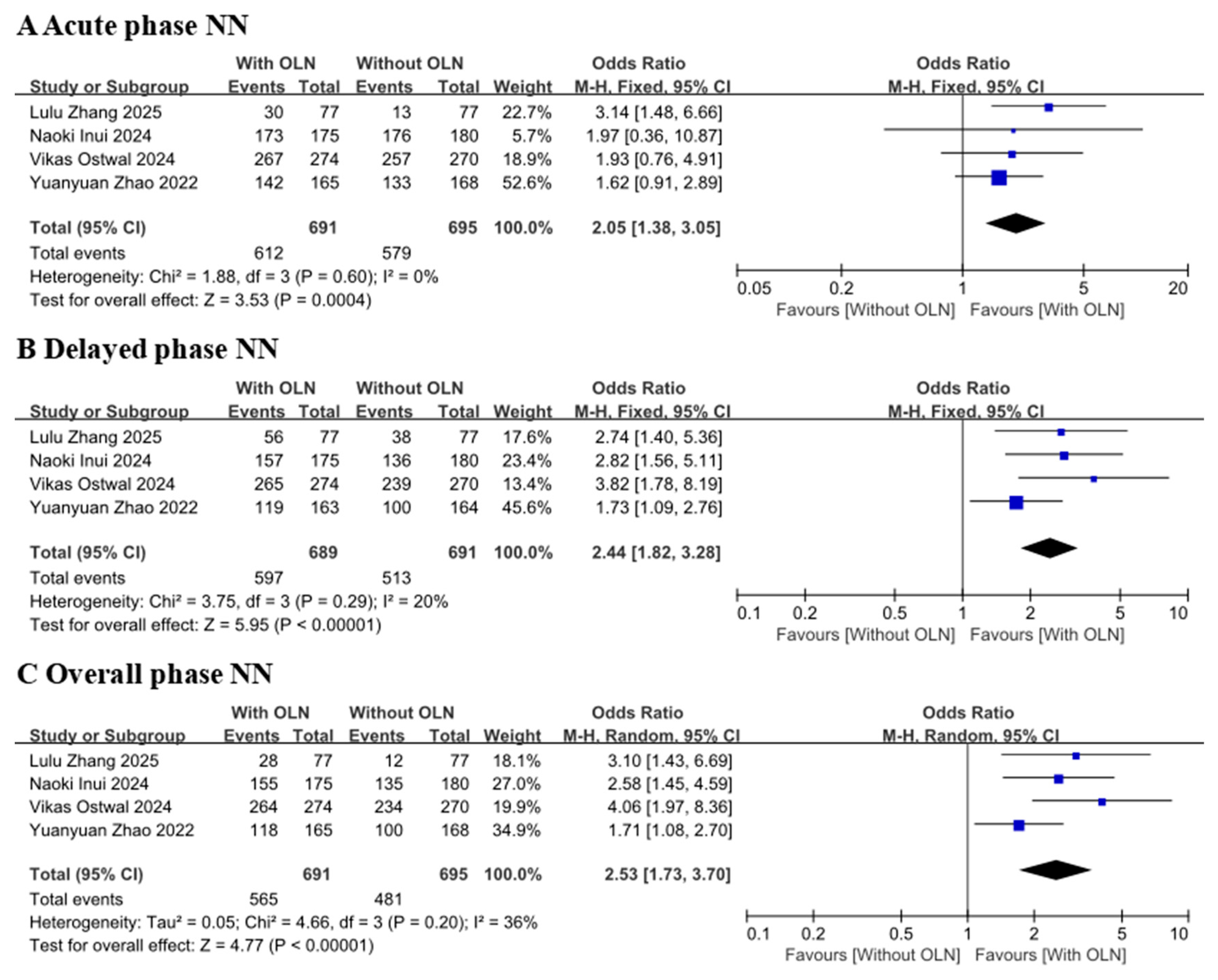

3.3.2. No Nausea Rate or No Vomiting Rate

3.4. Safety

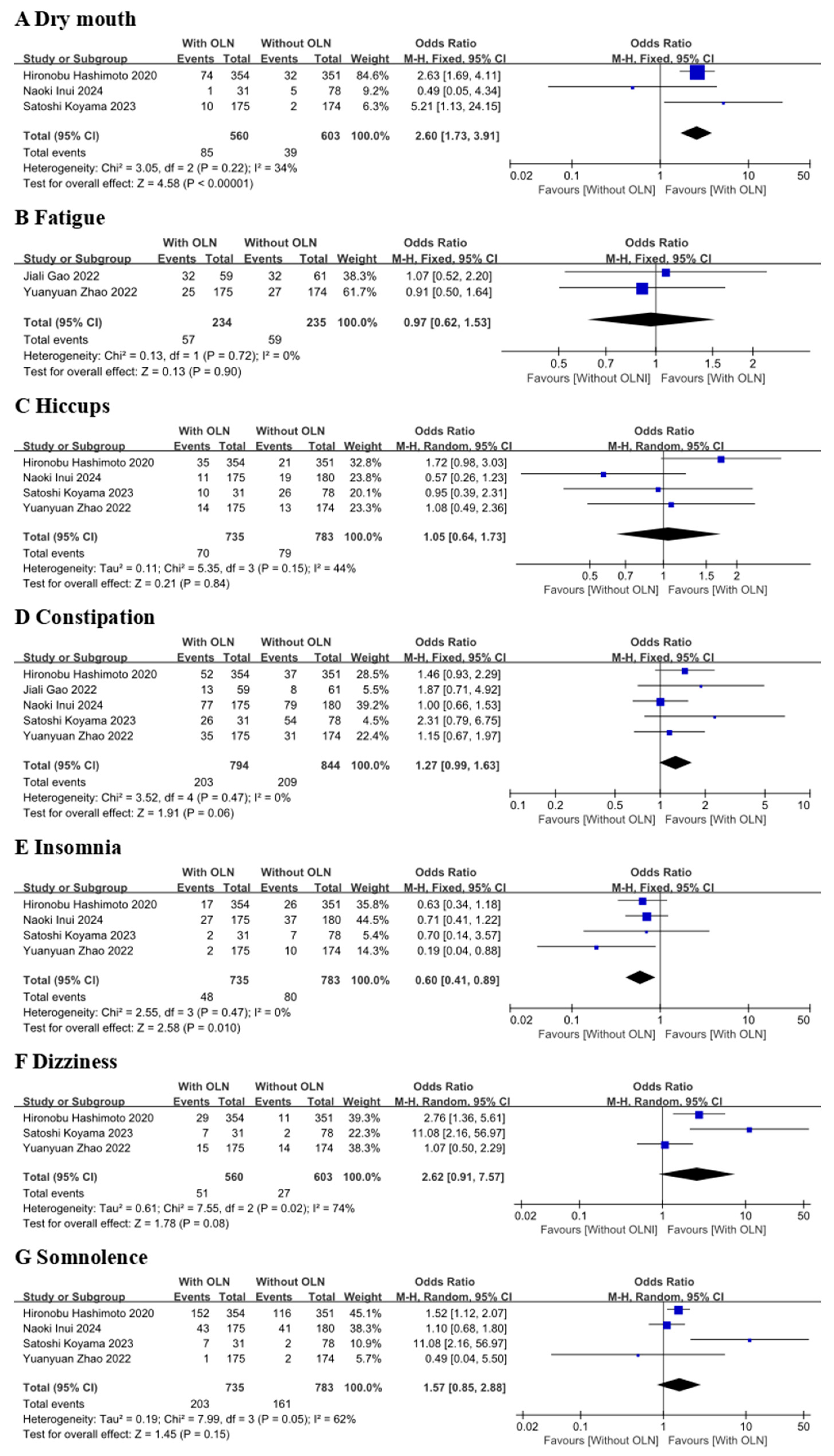

3.4.1. AEs Included in Controlled Clinical Trial Studies

3.4.2. AEs Included in the Single-Arm Experimental Group Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, K.D.; Huang, S.; Zhang, J.X.; Liu, G.Y.; Shao, Z.M. Association between delayed initiation of adjuvant CMF or anthracycline-based chemotherapy and survival in breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesketh, P.J.; Kris, M.G.; Grunberg, S.M.; Beck, T.; Hainsworth, J.D.; Harker, G.; Aapro, M.S.; Gandara, D.; Lindley, C.M. Proposal for classifying the acute emetogenicity of cancer chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelland, L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankhala, K.K.; Pandya, D.M.; Sarantopoulos, J.; Soefje, S.A.; Giles, F.J.; Chawla, S.P. Prevention of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting: A focus on aprepitant. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2009, 5, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molassiotis, A.; Affronti, M.L.; Fleury, M.; Olver, I.; Giusti, R.; Scotte, F. 2023 MASCC/ESMO consensus antiemetic guidelines related to integrative and non-pharmacological therapies. Support Care Cancer 2023, 32, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, S.K.F.; Goodall, S.; Lee, S.F.; DeAngelis, C.; Jocko, A.; Charbonneau, F.; Wang, K.; Pasetka, M.; Ko, Y.J.; Wong, H.C.Y.; et al. 2020 ASCO, 2023 NCCN, 2023 MASCC/ESMO, and 2019 CCO: A comparison of antiemetic guidelines for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2024, 32, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Yamanaka, T.; Hashimoto, H.; Shimada, Y.; Arata, K.; Matsui, R.; Goto, K.; Takiguchi, T.; Ohyanagi, F.; Kogure, Y.; et al. Randomized, double-blind, phase III trial of palonosetron versus granisetron in the triplet regimen for preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting after highly emetogenic chemotherapy: TRIPLE study. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyoshi, T.; Miyashita, H.; Matsuo, N.; Odawara, M.; Hori, M.; Hiraki, Y.; Kawanaka, H. Palonosetron versus Granisetron in Combination with Aprepitant and Dexamethasone for the Prevention of Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting after Moderately Emetogenic Chemotherapy: A Single-Institutional Retrospective Cohort Study. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 44, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roila, F.; Molassiotis, A.; Herrstedt, J.; Aapro, M.; Gralla, R.J.; Bruera, E.; Clark-Snow, R.A.; Dupuis, L.L.; Einhorn, L.H.; Feyer, P.; et al. 2016 MASCC and ESMO guideline update for the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27 (Suppl. S5), v119–v133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Yokokawa, T.; Kawaguchi, T.; Takada, S.; Tamaki, S.; Kawasaki, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Koizumi, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Sakata, Y.; et al. A multicenter, phase II trial of triplet antiemetic therapy with palonosetron, aprepitant, and olanzapine for highly emetogenic chemotherapy in breast cancer (PATROL-II). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Navari, R.M.; Qin, R.; Ruddy, K.J.; Liu, H.; Powell, S.F.; Bajaj, M.; Dietrich, L.; Biggs, D.; Lafky, J.M.; Loprinzi, C.L. Olanzapine for the Prevention of Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leucht, S.; Cipriani, A.; Spineli, L.; Mavridis, D.; Orey, D.; Richter, F.; Samara, M.; Barbui, C.; Engel, R.R.; Geddes, J.R.; et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: A multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013, 382, 951–962, Erratum in Lancet 2013, 382, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Chandler, J.; Welch, V.; Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: A new edition of the cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, ED000142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hashimoto, H.; Abe, M.; Tokuyama, O.; Mizutani, H.; Uchitomi, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Hoshina, Y.; Sakata, Y.; Takahashi, T.Y.; Nakashima, K.; et al. Olanzapine 5 mg plus standard antiemetic therapy for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (J-FORCE): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 242–249, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, S.; Ehara, H.; Donishi, R.; Morisaki, T.; Taira, K.; Fukuhara, T.; Fujiwara, K. Olanzapine for The Prevention of Nausea and Vomiting Caused by Chemoradiotherapy with High-Dose Cisplatin for Head and Neck Cancer. Yonago Acta Med. 2023, 66, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gao, J.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, C.; Chen, F.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Wu, Y.; Jin, Y.; et al. Olanzapine (5 mg) plus standard triple antiemetic therapy for the prevention of multiple-day cisplatin hemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A prospective randomized controlled study. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 6225–6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, F.; Hu, C.; Zhong, D.; Lu, M.; Yuan, Z.; Zhao, J.; Miao, J.; Li, Y.; et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial of olanzapine plus triple antiemetic regimen for the prevention of multiday highly emetogenic chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (OFFER study). eClinicalMedicine 2022, 55, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abe, M.; Kasamatsu, Y.; Kado, N.; Kuji, S.; Tanaka, A.; Takahashi, N.; Takekuma, M.; Hirashima, Y. Efficacy of Olanzapine Combined Therapy for Patients Receiving Highly Emetogenic Chemotherapy Resistant to Standard Antiemetic Therapy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 956785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, L.Y.; Qian, X.Y. Efficacy of olanzapine combined with triple antiemetic regimen in cisplatin-based multi-day chemotherapy. Zhejiang Clin. Med. J. 2024, 26, 1172–1174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, M.; Zhou, Q.; Xue, C.; Huang, R.; Diao, X.; Li, J.; Peng, J.; Zheng, Q.; Ni, M.; et al. Olanzapine combined with standard antiemetics for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in patients with germ cell tumor undergoing a 5-day cisplatin-based chemotherapy (NAVIGATE study): A phase III crossover trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 222, 115437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, N.; Suzuki, T.; Tanaka, K.; Karayama, M.; Inoue, Y.; Mori, K.; Yasui, H.; Hozumi, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Furuhashi, K.; et al. Olanzapine Plus Triple Antiemetic Therapy for the Prevention of Carboplatin-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2780–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ostwal, V.; Ramaswamy, A.; Mandavkar, S.; Bhargava, P.; Naughane, D.; Sunn, S.F.; Srinivas, S.; Kapoor, A.; Mishra, B.K.; Gupta, A.; et al. Olanzapine as Antiemetic Prophylaxis in Moderately Emetogenic Chemotherapy: A Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2426076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Minatogawa, H.; Izawa, N.; Shimomura, K.; Arioka, H.; Iihara, H.; Sugawara, M.; Morita, H.; Mochizuki, A.; Nawata, S.; Mishima, K.; et al. Dexamethasone-sparing on days 2-4 with combined palonosetron, neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, and olanzapine in cisplatin: A randomized phase III trial (SPARED Trial). Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iihara, H.; Shimokawa, M.; Hayasaki, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Abe, M.; Takenaka, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Arai, T.; Sakurai, M.; Mori, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of 5 mg olanzapine combined with aprepitant, granisetron and dexamethasone to prevent carboplatin-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with gynecologic cancer: A multi-institution phase II study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 156, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, T.; Lin, L.E.; Lin, Q.; Wu, S.G. Olanzapine 5 mg for Nausea and Vomiting in Patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Receiving Cisplatin-Based Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 9984738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nakashima, K.; Murakami, H.; Yokoyama, K.; Omori, S.; Wakuda, K.; Ono, A.; Kenmotsu, H.; Naito, T.; Nishiyama, F.; Kikugawa, M.; et al. A Phase II study of palonosetron, aprepitant, dexamethasone and olanzapine for the prevention of cisplatin-based chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with thoracic malignancy. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 47, 840–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.; Inui, N.; Karayama, M.; Yasui, H.; Hozumi, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Furuhashi, K.; Fujisawa, T.; Enomoto, N.; Nakamura, Y.; et al. Olanzapine-containing antiemetic therapy for the prevention of carboplatin-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2019, 84, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, M.; Hirashima, Y.; Kasamatsu, Y.; Kado, N.; Komeda, S.; Kuji, S.; Tanaka, A.; Takahashi, N.; Takekuma, M.; Hihara, H.; et al. Efficacy and safety of olanzapine combined with aprepitant, palonosetron, and dexamethasone for preventing nausea and vomiting induced by cisplatin-based chemotherapy in gynecological cancer: KCOG-G1301 phase II trial. Support Care Cancer 2016, 24, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, J.; Hasegawa, A.; Kudo, T.; Otsuka, T.; Yasui, M.; Matsuda, C.; Haraguchi, N.; Ushigome, H.; Nakai, N.; Abe, T.; et al. A phase II study of the safety of olanzapine for oxaliplatin based chemotherapy in coloraectal patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Navari, R.M.; Gray, S.E.; Kerr, A.C. Olanzapine versus aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A randomized phase III trial. J. Support Oncol. 2011, 9, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Hong, S.; Yang, Y.; Fang, W.; Luo, F.; Chen, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Olanzapine-Based Triple Regimens Versus Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonist-Based Triple Regimens in Preventing Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting Associated with Highly Emetogenic Chemotherapy: A Network Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 2018, 23, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ithimakin, S.; Theeratrakul, P.; Laocharoenkiat, A.; Nimmannit, A.; Akewanlop, C.; Soparattanapaisarn, N.; Techawattanawanna, S.; Korphaisarn, K.; Danchaivijitr, P. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of aprepitant versus two dosages of olanzapine with ondansetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving high-emetogenic chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2020, 28, 5335–5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajpai, J.; Kapu, V.; Rath, S.; Kumar, S.; Sekar, A.; Patil, P.; Siddiqui, A.; Anne, S.; Pawar, A.; Srinivas, S.; et al. Low-dose versus standard-dose olanzapine with triple antiemetic therapy for prevention of highly emetogenic chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with solid tumours: A single-centre, open-label, non-inferiority, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosa, A.S.M.; Hossain, A.M.; Lavoie, B.J.; Yoo, I. Patient-Related Risk Factors for Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: A Systematic Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| AEs | E | n | N | Prop. (%) | Heterogeneity (p, I2) | RD | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constipation | 9 | 350 | 625 | 56.0 | p < 0.00001, I2 = 98% | 0.51 | 0.27–0.75 |

| Somnolence | 9 | 351 | 625 | 56.2 | p < 0.00001, I2 = 94% | 0.51 | 0.37–0.66 |

| Hiccups | 7 | 250 | 545 | 45.9 | p < 0.00001, I2 = 98% | 0.38 | 0.14–0.62 |

| Dry mouth | 3 | 209 | 332 | 63.0 | p = 0.93, I2 = 0% | 0.63 | 0.58–0.68 |

| Insomnia | 3 | 108 | 332 | 32.5 | p = 0.73, I2 = 0% | 0.32 | 0.27–0.37 |

| Dizziness | 2 | 24 | 97 | 24.7 | p < 0.00001, I2 = 95% | 0.12 | 0.07–0.18 |

| Anxious | 2 | 54 | 275 | 19.6 | p = 0.32, I2 = 0% | 0.19 | 0.15–0.24 |

| Fatigue | 2 | 175 | 275 | 63.6 | p = 0.10, I2 = 62% | 0.64 | 0.55–0.73 |

| Appetite loss | 2 | 188 | 275 | 68.4 | p = 0.001, I2 = 90% | 0.69 | 0.51–0.86 |

| Anorexia | 2 | 32 | 73 | 43.8 | p = 0.09, I2 = 65% | 0.44 | 0.25–0.63 |

| Headache | 2 | 86 | 275 | 31.3 | p = 0.003, I2 = 92% | 0.31 | 0.12–0.50 |

| Diarrhea | 2 | 17 | 97 | 17.5 | p < 0.0001, I2 = 94% | 0.06 | 0.02–0.11 |

| Nephrotoxicity | 1 | 3 | 33 | 9.1 | / | / | / |

| Hepatotoxicity | 1 | 15 | 33 | 45.5 | / | / | / |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 | 20 | 33 | 60.6 | / | / | / |

| Anemia | 1 | 24 | 33 | 72.7 | / | / | / |

| Neutropenia | 1 | 28 | 33 | 84.8 | / | / | / |

| Leukopenia | 1 | 24 | 33 | 72.7 | / | / | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gong, W.; Qie, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, P.; Gao, J.; Wang, M. Olanzapine Plus Triple Antiemetic Therapy for the Prevention of Platinum-Based Delayed-Phase Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: A Meta-Analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2026, 33, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010027

Gong W, Qie H, Xu Y, Wang P, Gao J, Wang M. Olanzapine Plus Triple Antiemetic Therapy for the Prevention of Platinum-Based Delayed-Phase Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: A Meta-Analysis. Current Oncology. 2026; 33(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Wenlin, Hongxin Qie, Yuxiang Xu, Peiyuan Wang, Jinglin Gao, and Mingxia Wang. 2026. "Olanzapine Plus Triple Antiemetic Therapy for the Prevention of Platinum-Based Delayed-Phase Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: A Meta-Analysis" Current Oncology 33, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010027

APA StyleGong, W., Qie, H., Xu, Y., Wang, P., Gao, J., & Wang, M. (2026). Olanzapine Plus Triple Antiemetic Therapy for the Prevention of Platinum-Based Delayed-Phase Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: A Meta-Analysis. Current Oncology, 33(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010027