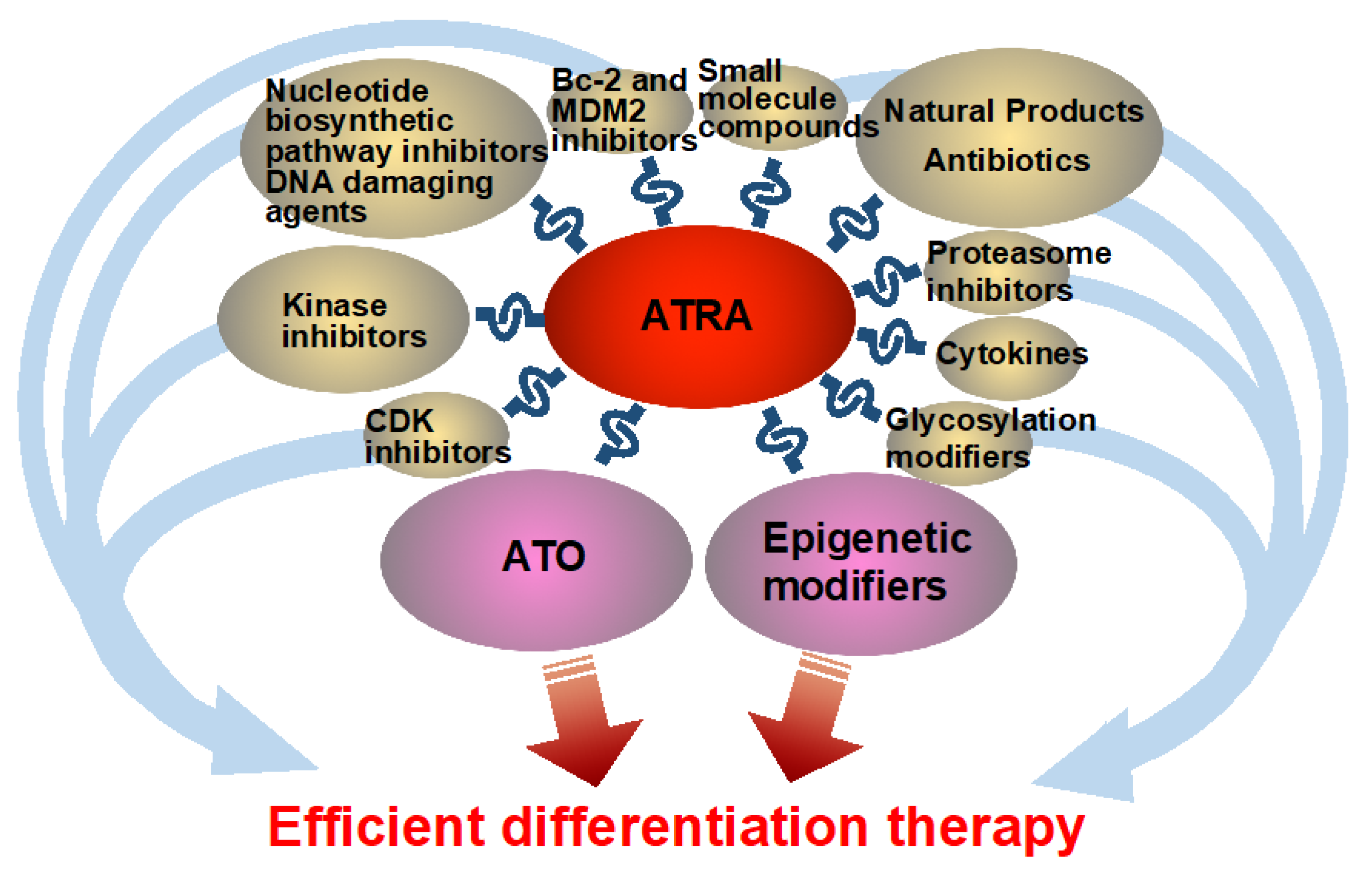

Reawakening Differentiation Therapy in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Comprehensive Review of ATRA-Based Combination Strategies

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Studies of ATRA-Based Combination Therapies

2.1. ATRA and ATO in APL

2.2. ATRA Combined with Epigenetic Modifiers

3. Pre-Clinical Strategies Enhancing ATRA-Induced Differentiation

3.1. Combination of ATRA with CDK Inhibitors

3.2. Combination of ATRA with Kinase Inhibitors

3.3. Combination of ATRA with ATO (Pre-Clinical Studies)

3.4. Combination of ATRA with Epigenetic Modifiers (Pre-Clinical Studies)

| Pre-Clinical Studies of Epigenetic Modifiers | |||

| Differentiation Agent(s) | Action | Model Level | Ref |

| Valproic acid (VPA) (HDAC inhibitor) | VPA suppressed NB4 cell proliferation, an effect that was potentiated by ATRA. Co-treatment also upregulated myeloid transcription factors (C/EBPα, β, ε, and PU.1), facilitating differentiation. | Cell line (NB4 cells). | [58] |

| VPA | VPA combined with ATRA promoted autophagy and differentiation in ATRA-sensitive NB4 cells and also in ATRA-resistant NB4R and THP-1 cell lines. | Cell line (NB4, ATRA-resistant NB4R and THP-1 cells). | [59] |

| VPA, vorinostat/suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) (HDAC inhibitor) | In an APL mouse model, SAHA was shown to target leukemia-initiating cells. Co-treatment with ATRA, VPA, and SAHA effectively induced complete remission and decreased LIC frequency. | In vivo (APL model mice). | [60] |

| VPA | In several APL mouse models, VPA induced terminal differentiation; however, discontinuation of VPA led to rapid relapse. Moreover, VPA increased LIC activity. Unlike ATRA or arsenic, VPA did not promote degradation of PML-RARA. | Primary blasts/in vivo (PML-RARA-transformed primary hematopoietic progenitors and APL mouse models). | [61] |

| Troglitazone (an antidiabetic drug, also identified as a ligand for PPAR gamma). | Co-treatment with troglitazone and a ligand selective for RAR (ATRA, ALART1550), RXR (LG100268), or both receptors (9-cis RA) effectively inhibited clonal growth in several myeloid leukemia cell lines. | Cell line (NB4, HL-60, U937, ML-1 and THP-1 cells). | [62] |

| Low-dose AZA combined with PPARγ ligands [e.g., pioglitazone (PGZ)], and ATRA | In HL-60 and U937 cells, as well as in about 50% of primary AML samples, the drug combination effectively suppressed proliferation and promoted differentiation. AML blasts treated with ATRA, AZA, and PGZ exhibited increased ROS levels and phagocytic activity. | Cell line/primary blasts (HL-60, MV4-11, MOLM-13, U937 cells, 14 primary AML cells). | [19] |

| Entinostat (HDAC class-I selective inhibitor) | Entinostat induced differentiation in AML cell lines and primary AML cells, with this effect being further augmented by ATRA. Acting as a priming agent for ATRA-mediated differentiation, entinostat exerts its effects independently of RARβ2. | Cell line/primary blasts (Kasumi-1, HL-60, NB-4, U937, K562, KG-1 and 46 primary AML blasts). | [63] |

| Trichostatin A (TSA), trapoxin A (TPX) (HDAC inhibitors [HDIs]) | TSA and/or TPX induced differentiation in both myeloid (e.g., U937) and erythroid (e.g., K562) cell lines. Co-treatment with ATRA resulted in a synergistic enhancement of differentiation. In clinical AML specimens ranging from M0 to M7, TSA alone elicited morphological and phenotypic changes in 12 of 35 samples (34%). | Cell line/primary blasts (K562, HEL, U937, HL60, HL60/RA (ATRA resistant HL60), NB4, MEG-O1 cells and 35 clinical specimens from AML). | [64] |

| Sodium phenylbutyrate (SB)(HDAC inhibitor) | SB in combination with ATRA synergistically inhibited colony formation and promoted CD11b expression. The combination significantly affected S-phase progression, with the interaction shifting from antagonistic at low ATRA concentrations to synergistic at higher levels (>0.5 µM). | Cell line (ML-1 cells). | [65] |

| Cell-permeable form of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) | AML blasts with IDH1 mutations generate 2-HG, leading to hypermethylation. ATRA selectively impaired viability and induced apoptosis in these cells. Cell-permeable 2-HG sensitized wild-type AML cells to ATRA-induced differentiation. In vivo, ATRA reduced tumor burden and prolonged survival in mice bearing mutant IDH1 AML. | Cell line/primary blasts/in vivo (HL-60, MOLM14, NB4, 14 primary AML patient samples. A xenograft model based on immunodeficient NOD–scid IL2rγnull (NSG) mice with primary AML samples, or MOLM14 carrying the IDH1– R132H mutation). | [68] |

| 2-HG | 2-HG specifically activates the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in IDH-mutant AML cells, increasing their sensitivity to the combination of ATRA and vitamin D (or a VDR agonist). | Cell line/primary blasts/in vivo (HL60, U937, KG1a, THP1IDH1WT, THP1IDH1R132H, HL60IDH2WT, HL60IDH2R172K, 24 primary AML patient samples, a xenograft model). | [69] |

| Tranylcypromine (TCP) (Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1 (LSD1) Inhibitor) | Inhibition of LSD1 enhanced H3K4 dimethylation, especially at myeloid differentiation-related genes. TCP combined with ATRA significantly suppressed engraftment of primary human AML cells in NOD-SCID mice and showed stronger anti-leukemic activity, targeting leukemia-initiating cells, than either treatment alone. | Cell line/primary blasts/in vivo (HL-60, TEX [derived from primitive human cord blood cells, ATRA insensitive] cells. Normal bone marrow mononuclear cells, primary AML cells (n = 5), umbilical cord blood cells (n = 5). In vivo treatment of AML in NOD-SCID and NSG mice, Secondary transplants of AML-engrafted mice). | [70] |

| A novel retinoic/butyric hyaluronan ester (HBR) | In RA-sensitive NB4 cells, HBR promoted terminal differentiation and growth arrest, while in RA-resistant NB4.007/6 cells, it inhibited proliferation through apoptosis. Treatment with HBR significantly increased survival in NB4- or P388-xenografted mice. | Cell line/in vivo (NB4, and on its RA-resistant subclone, NB4.007/6, SCID/NB4 model and the P388 lymphocytic leukemia in DBA mice). | [73] |

| Selenite (DNMT inhibitor) | By targeting PML/RARα for degradation, selenite suppressed survival and proliferation of NB4 cells. While selenite alone did not induce differentiation, it potentiated ATRA-mediated differentiation in these cells. | Cell line (NB4). | [77] |

| Pre-Clinical Studies of De Novo Nucleotide Biosynthetic Pathway Inhibitors and DNA Damaging Agents | |||

| Differentiation Agent(s) | Action | Model Level | Ref |

| ML390, BRQ (dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH)inhibitors) | In ER-homeobox (HOX) A9–transduced primary murine bone marrow cells, terminal differentiation occurs following β-estradiol withdrawal. Through a phenotypic screen using this model, DHODH inhibitors were found to bypass the differentiation block, reduce leukemia-initiating cells, decrease leukemic burden, and enhance survival. | Cell line/primary blasts/in vivo (THP-1, U937, ER-HoxA9 GMP Cell Lines, the HoxA9 + Meis1 or MLL/AF9 primary leukemia cells. Subcutaneous xenograft tumor mice models, disseminated intravenous xenograft leukemia mice models, patient AML sample engrafted (PDX) mice). | [78] |

| BAY 2402234 (DHODH inhibitor) | BAY2402234 induces differentiation in many myeloid cell lines, and AML cell line xenografts, as well as PDX model. | Cell line/in vivo (THP-1, MV4-11, TF-1, MOLM-13, HEL, SKM-1, NOMO-1, UOC-M1 and EOL-1 cells. Tumor xenografted NOG or NOD/SCID mice). | [79] |

| 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside (AICAr) | AICAr enhanced ATRA-driven differentiation in NB4 cells and independently induced monocyte–macrophage markers in U937 cells, effects that were mediated via MAPK activation. | Cell line (HL-60, NB4, U937) | [80] |

| AICAr, brequinar (DHODH inhibitor) | AICAr induced macrophage-like differentiation in a subset of primary non-APL AML blasts. RNA-seq analysis demonstrated that this treatment inhibited pyrimidine metabolism. | primary blasts (35 primary AML cells) | [81] |

| Triciribine (Akt inhibitor and inhibitor of nucleotide synthesis) | In NB4 and HL-60 cells, differentiation correlated with ERK activation. Triciribine treatment enriched pathways related to cytokine–cytokine receptor interactions and hematopoietic cell lineage, according to pathway analysis. | Cell line (NB4, HL-60 cells). | [82] |

| 6-benzylthioinosine (6BT), a closely related compound of 6-methylthioinosine, which is a potent inhibitor of de novo purine synthesis | 6BT induced monocytic differentiation and cell death in myeloid leukemia cell lines, with minimal cytotoxicity toward nonmalignant cells, including fibroblasts, normal bone marrow, and endothelial cells. In xenografted mice, 6BT effectively inhibited the growth of MV4-11 and HL-60 tumors. | Cell line/primary blasts/in vivo (HL-60, OCI-AML3, OCIM2, MV-411, HNT34 cells. 5 primary AML samples. fibroblasts, normal bone marrow, and endothelial cells. HL-60 or MV-411 xenograft mice). | [83] |

| Pyrimethamine (PMT)(dihydrofolate reductase [DHFR] antagonist) | Oral PMT treatment was effective in two xenograft mouse models. PMT strongly inhibited human AML cell lines and primary patient cells, while sparing CD34+ hematopoietic cells from healthy donors. | Cell line/primary blasts/in vivo (Human AML cell lines, primary patient cells, two xenograft mice models, and CD34+ cells from healthy donors). | [84] |

| Topotecan (TPT)(topoisomerase I inhibitor) | TPT synergized with ATRA to induce DNA damage and trigger caspase-dependent apoptosis, with RARα mediating this effect. The combined efficacy was confirmed in HL-60 xenografted mice. | Cell line/in vivo (HL60, NB4, U937 cells and HL60 xenografted nude mice). | [85] |

| Aclacinomycin (ACLA) (topoisomerase I/II inhibitor) | ATRA and ACLA induced granulocytic differentiation in HL-60 and NB4 cells, concomitant with increased migratory and invasive activity. ACLA-driven differentiation upregulated MMP-9, whereas ATRA decreased MMP-9 and induced urokinase plasminogen activator mRNA expression. | Cell line (HL-60, NB4 cells). | [86] |

| ICRF-154, 193 (topoisomerase II inhibitor) | Both ICRF-154 and ICRF-193 promoted differentiation of APL cell lines and primary cells from APL patients, and synergized with ATRA to suppress cell proliferation and enhance differentiation. | Cell line/primary blasts (NB4, HT-93, HL-60, U937 and 3 primary APL cells). | [87] |

| 1-(2-deoxy-2-methylene-beta-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl) cytidine (DMDC)(cytidine deaminase-resistant analogue of ara-C) | DMDC suppressed proliferation of APL and AML cell lines and promoted differentiation in APL cells. In NB4 cells, DMDC combined with ATRA induced differentiation synergistically, with comparable effects observed in primary APL patient cells. | Cell line/primary blasts (HL-60, NB4, U937, and HT93 cell line. 3 primary APL cells). | [88] |

| Ara-C (pyrimidine nucleoside analog) | Both ATRA and ara-C triggered apoptosis in CML cells, with ara-C showing greater efficacy. Their combined treatment resulted in an additive, rather than synergistic, effect. | Primary blasts (Freshly isolated cells from 10 patients with chronic-phase CML). | [89] |

| 2′-deoxycoformycin (dCF), 9-beta-D-arabinofuranosyladenine (Ara A), fludarabine (FLU), cladribine (CdA)(deoxyadenosine analogs) | Combined treatment with dCF and Ara A effectively induced differentiation in monocytoid leukemia cells (U937, THP-1, P39/TSU, JOSK-M). Among myeloid leukemia cells (NB4, HL-60), CdA was the most potent analog in promoting differentiation, with or without ATRA. | Cell line (K562, HL-60, NB4, KG-1, ML-1, U937, THP-1, P39/TSU, JOSK-M cells). | [90] |

| dCF and 2′-deoxyadenosine (dAd) (adenosine deaminase inhibitor) | NB4 cells exhibited granulocytic differentiation in response to ATRA or dAd plus dCF, but not to ara-C. Pre-treatment with ATRA enhanced the differentiation effect of dAd plus dCF, whereas pretreatment with dAd plus dCF before ATRA had a reduced impact. | Cell line (K562, HL-60 and NB4 cells). | [91] |

| Neplanocin A (NPA, a potent S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase inhibitor), dCF, deoxyadenosine (dAd). | Both NPA and dAdo plus dCF synergized with ATRA to promote myeloid differentiation in NB4 cells. Pre-treatment with ATRA markedly potentiated the differentiation-inducing effect of dAdo plus dCF, whereas pretreatment with dAdo plus dCF prior to ATRA was less effective. | Cell line (NB4, K562, U937 cells). | [92] |

3.5. Combination of ATRA with De Novo Nucleotide Biosynthetic Pathway Inhibitors and DNA Damaging Agents

3.6. Combination of ATRA with Bcl-2 Inhibitors and MDM2 Inhibitors

3.7. Combination of ATRA with Proteasome Inhibitors

3.8. Combination of ATRA with Cytokines

4. Novel Molecular and Natural Differentiation Enhancers

4.1. Combination of ATRA with Glycosylation Modifiers

| Pre-Clinical Studies of Glycosylation Modifiers | |||||

| Differentiation Agent(s) | Action | Model Level | Ref | ||

| 6-alkynylfucose (6-AF) (fucosylation inhibitor) | ATRA or 6AF alone reduced fucosylation, whereas their combination produced a more pronounced decrease. Both 6AF and ATRA also synergistically enhanced differentiation in NB4 (APL) and HL-60 (AML) cells. | Cell line (NB4 and HL-60 cells). | [120] | ||

| Dronabinol (inducers of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase) | Dronabinol, used to treat chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, induced activation of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase, resulting in differentiation of AML blasts in vitro and in vivo. | Cell line/primary blasts (Jurkat, MOLM14, primary AML cells). | [121] | ||

| Atorvastatin, Rosuvastatin, Fluvastatin. (Inhibitors of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, which regulates not only cholesterol, but dolichol and ubiquinone. Dolichol mediates glycosylation.) | It was demonstrated that atorvastatin and fluvastatin effectively induced differentiation and apoptosis in NB4 APL cells, an effect regulated by Rac1/Cdc42 activation and its downstream c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling. | Cell line/primary blasts (NB4, RA resistant variants NB4.007/6, NB4.300/6, bone marrow or peripheral blood from patients with AML [AML-M2, AML-M5, and unclassified relapsed AML]). | [126] | ||

| Clinical Study of Glycosylation Modifier | |||||

| Differentiation Agent(s) | Status | Patients Number | Dose and Schedule | Results | Ref |

| Dronabinol | Early clinical (case report). | A 90-year old patient with AML | Hydroxyurea (HU, 2–3 × 1 g) was initially given for leukocytosis (~1.0 × 105/µL, 80% blasts) and tapered as neutrophils declined. Dronabinol 2.5% was added, titrated to 6 drops twice daily. | Leukocytosis resolved, HU was discontinued, and dronabinol maintained. Peripheral blood blasts nearly disappeared, and neutrophil and platelet counts normalized. | [121] |

4.2. Natural Products with Differentiation-Enhancing Effects

| Studies of Natural Products | ||||

| Differentiation Agent(s) | Primary Raw Material | Results | Model Level | Ref |

| (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) | Major active polyphenol extracted from green tea | In PML/RARα mice, EGCG administration reversed anemia, leukocytosis, and thrombocytopenia, and prolonged survival. In NB4 cells, EGCG upregulated neutrophil differentiation markers (CD11b, CD14, CD15, CD66) and, together with N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), inhibited ROS production. | Cell line (APL model mice, NB4 cells). | [126] |

| Treatment with EGCG significantly upregulated death-associated protein kinase 2 (DAPK2), accompanied by increased cell death in AML cells. | Cell line (HL60, NB4, retinoic-acid resistant NB4-R2 and HL60-R411). | [129] | ||

| Treatment with EGCG and ATRA markedly upregulated PTEN in HL-60, NB4, and THP-1 cells, paralleled by increased CD11b expression. The combination synergistically facilitated PML/RARα degradation, restored PML expression, and elevated nuclear PTEN levels. | Cell line (HL-60, NB4 and THP-1). | [130] | ||

| Dihydromyricetin (DMY), a 2,3-dihydroflavonol compound | The main bioactive component extracted from Ampelopsis grossedentata | DMY sensitized NB4 cells to ATRA-induced growth inhibition, NBT reduction, CD11b expression, and upregulation of myeloid regulators (PU.1, C/EBPs). The DMY-enhanced differentiation appeared independent of PML-RARα and was mediated via activation of the p38–STAT1 signaling pathway. | Cell line (NB4 cells). | [131] |

| Wogonin (5,7-dihydroxy-8-methoxyflavone) | Monoflavonoid extracted from Scutellariae radix, a traditional Chinese medicine Huang-Qin | Wogonin promotes apoptosis in malignant T cells and inhibits growth of human T-cell leukemia xenografts. Importantly, normal T lymphocytes are largely unaffected, which is attributed to differential redox regulation in malignant versus normal cells. | Cell line (Malignant T-cell lines CEM, Molt-4, DND-41, JurkatJ16, J16neo, J16bcl-2, Jurkat A3, Jurkat A3 deficient in FADD, Jurkat cells deficient in LAT, SLP76 and PLCγ1). | [126] |

| In U937 and HL-60 cells, wogonin suppressed proliferation via G1-phase arrest and induction of differentiation. Wogonoside significantly enhanced PLSCR1 transcription, accompanied by modulation of differentiation- and cell cycle-related genes, including increased p21 Waf1/Cip1 and decreased c-Myc expression. | Cell line/primary blasts (3 primary leukemic cells from AML patients, U937 and HL-60 cells). | [134] | ||

| Wogonoside increased PLSCR1 expression and its binding to the 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptor 1 (IP3R1) promoter in primary AML cells. Activation of IP3R1 by wogonoside promoted Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum, contributing to cell differentiation. | Primary blasts/in vivo (23 Primary leukemic cells from newly diagnosed AML patients without prior therapy, U937 xenografts mice model and primary AML). | [135] | ||

| Jiyuan oridonin A (JOA), kaurene diterpenoid compound | Isolated from Isodon rubescensin | JOA markedly suppressed proliferation and induced differentiation, associated with G0/G1 cell-cycle arrest and impaired colony-forming ability. | Cell line (MOLM-13, MV4-11 and THP-1). | [136] |

| JOA inhibits proliferation and induces G0/G1 cell-cycle arrest and differentiation in both imatinib-sensitive and -resistant CML cells, including those with the BCR-ABL-T315I mutation, by suppressing BCR-ABL/c-MYC signaling. | Cell line (Human K562 cells [BCR-ABL-native CML], murine BaF3 cells carrying wild-type p210 BCR-ABL [BaF3-WT] and point mutations of p210 BCR-ABL [T315I, E255K, G250E, M351T, Y253F, F359V, E255V, H296P, Q252H, F311L, M244V and F317L]). | [137] | ||

| Silymarin (SM) | Extracted from milk thistle (Silybum marianum) | Treatment with SM suppressed proliferation and potentiated ATRA-induced apoptosis in NB4 cells. | Cell line (NB4 cells). | [140] |

| Pharicin B | Natural entkaurene diterpenoid derived from Isodon pharicus leaves | Pharcin B induces myeloid differentiation in combination with ATRA in several AML cell lines and primary leukemia samples, enhancing ATRA-dependent transcriptional activity of RARα, which contributes to this effect. | Cell line/primary blasts (12 primary AML patients, U937, THP-1, NB4, and NB4-derived ATRA-resistant cell lines NB4-MR2, NB4-LR1, and NB4-LR2, as well as NB4FLAG-RARα and U937FLAG-RARα cell lines with stable expression of FLAG-RAR-α. | [141] |

| Notopterol | One type of coumarin, is an active monomer extracted from N. incisum | Inhibited the growth leukemia cells (IC50 [µM]: HL-60; 40.32 µM, Kasumi-1; 56.68, U937; 50.69) Notopterol also induced differentiation and G0/G1 arrest in HL-60 cells. | Cell line (HL-60, Kasumi-1, U937 cells). | [143] |

| Fucoidan | A natural substance derived from marine algae | Fucoidan induced apoptosis at 20 µg/mL in APL (NB4) but not in non-APL (Kasumi-1) cells when combined with ATO. In NB4 cells, fucoidan with ATO and/or ATRA efficiently promoted differentiation, and fucoidan plus ATRA or ATO delayed tumor growth while inducing differentiation. | Cell line/in vivo (NB4, Kasumi-1, APL-bearing mice). | [145] |

| Cotylenin A (CN-A) | Isolated from the metabolites of a simple eukaryote, a cladosporium sp. as plant growth regulators | CN-A efficiently induced differentiation in myeloid cell lines (HL-60, NB4, NB4/R, ML-1, and HT-93). In NB4 cells, CN-A promoted monocytic differentiation, as indicated by increased α-naphthyl acetate esterase activity. | Cell line (ML-1, HT-93, U937, TSU, P39/Fuji, JOSK-M, HL-60, NB4, retinoid-resistant NB4 [NB4/R]). | [126] |

| CN-A induced differentiation in 9 of 12 primary patient samples. Synergistic effects were observed when CN-A was combined with ATRA (3 of 12) or vitamin D3 (8 of 12). | Primary blasts (12 primary AML specimens). | [148] | ||

| Emodin | Extracted from the root and rhizome of Rheum palmatum L. | Emodin sensitized ATRA induced differentiation in NB4, MR2 and primary AML samples. Emodin potently inhibits phosphorylation of Akt and efficiently inhibits mTOR downstream targets. | Cell line/primary blasts (NB4, MR2 [ATRA resistant NB4], 21 primary AML specimens). | [153] |

| Ellagic acid (EA) | EA is a polyphenolic compound found in fruits and berries | EA induced apoptosis and differentiation of HL-60 cells. In addition, EA sensitized ATRA induced differentiation. | Cell line (HL-60, NB4 cells). | [154] |

| Securinine | Major alkaloid natural product from the root of the plant securinega suffruticosa. | Securinine promoted monocytic differentiation in HL-60 and THP-1 cells and in several AML and one CML primary sample. It also significantly inhibited proliferation at 10–15 µM in various cell lines and in HL-60 xenograft models. | Cell line/primary blasts/in vivo (HL-60, THP-1, OCI-AML3, MV411, NB4, Nomo, U937 cells. 6 primary AML and CML samples. HL-60 xenografted mice). | [155] |

| Methyl jasmonate (MJ) | Jasmonates are potent lipid regulators in plants | MJ at 0.4 mM effectively upregulated CD15 and CD14, but not CD33, in HL-60 cells, inducing granulocytic differentiation with partial monocytic characteristics. | Cell line (HL-60, THP-1). | [158] |

| Microarray analysis revealed that MJ, isopentenyladenine, and CN-A, but not vitamin D3 or ATRA, induced expression of the calcium-binding protein S100P. The MJ derivative, methyl 4,5-didehydrojasmonate, was 30-fold more potent than MJ. | Cell line/primary blasts (8 primary AML specimens, HL-60). | [159] | ||

| Genistein | Identified as the predominant isoflavone in soybean. | 10 µg/mL of genistein efficiently reduced cell numbers, induced expression of OKM1 in HL-205 and benzidine positive cells in K-562-J, respectively. | Cell line (HL-205 [derivative of HL-60], K-562-J [derivative of K-562]). | [161] |

| Genistein (10–25 µM) induced CD11b expression and G2/M cell-cycle arrest, effects that were enhanced by ATRA. MEK/ERK activation and accumulation of reactive oxygen species contributed to genistein-induced differentiation. | Cell line (HL-60, NB4 cells). | [162] | ||

| Resveratrol | A phytoalexin found in grapes and other food products. | Resveratrol (10 µM, 3 days) promoted CD11b expression in HL-60, NB4, U937, THP-1, and ML-1 cells, with additive effects observed upon co-treatment with ATRA or vitamin D3. At 20 µM, it induced NBT reduction and morphological differentiation in 8 of 19 primary leukemia samples. | Cell line/primary blasts (HL-60, NB4, U937, THP-1, ML-1, Kasumi-1, 19 primary AML, MDS and ALL samples). | [163] |

| Caffeic acid (CA) | A phenolic plant compound | ATRA-induced differentiation was potentiated by CA, with NBT reduction assays demonstrating an additive effect. | Cell line (HL-60 cells). | [164] |

| PC-SPES | Patented mixture of eight herbs | PC-SPES suppressed growth and promoted differentiation in HL-60 and NB4 leukemia cells, but enhanced proliferation of normal myeloid-committed CFU-GM cells. | Cell line (HL-60, NB4, U937 and THP-1 cells). | [166] |

| Vibsanin A | A vibsane-type diterpenoid isolated from the leaves of Viburnum odoratissimum | Vibsanin A promoted monocytic differentiation in HL-60 cells, megakaryocytic differentiation in CML cells, and induced differentiation in 10 of 11 primary AML samples in a concentration-dependent manner (maximum 10 µM). In mouse xenograft models, it extended host survival, effects mediated via protein kinase C activation and the Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway. | Cell line/primary blasts/in vivo (HL-60, U937 and NB4 cells, Xenografted mice [Injected cells were from spleen of leukemic Mll-AF9 transgenic mice, or HL-60 cells]. 11 primary AML cells). | [168] |

| Inducers Those Can Serve As Antibiotics | ||||

| Differentiation Agent(s) | Primary Raw Material | Results | Model Level | Ref |

| Nargenicin | Identified from the novel actinomycete strain CS682 | Nargenicin (200 µM) induced differentiation in HL-60 cells and enhanced differentiation induced by vitamin D3 and ATRA. This effect was primarily mediated through the PKCβ1/MAPK pathways. | Cell line (HL-60 cells). | [126] |

| Deamino-hydroxy-phoslactomycin B (HPLM) | A biosynthetic precursor of phoslactomycin | HPLM induced differentiation in HL-60 cells via mechanisms distinct from those of ATRA and vitamin D3, which upregulate RARβ and 24OHase. | Cell line (HL-60 cells). | [169] |

| Salinomycin | A polyether ionophore antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces albus | Salinomycin combined with ATRA promoted differentiation by inhibiting β-catenin, which resulted in upregulation of PU.1 and C/EBPs and downregulation of c-Myc. | Cell line/primary blasts (Non-APL AML cells, primary AML cells). | [170] |

4.3. Antibiotic-Derived Differentiation Enhancers

4.4. Synthetic Small-Molecule Differentiation Inducers

| Synthesized Small Molecule Compound Inducers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiation Agent(s) | Strategy for Identification | Results | Model Level | Ref |

| LG-362B | A library of more than 100 synthesized compounds was screened for inhibition of APL cell proliferation. | LG-362B promoted differentiation in both APL and ATRA-resistant APL cells and in transplantable mouse models with ATRA-sensitive or resistant cells. Administration of 10 mg/kg LG-362B to HL-60 xenografted mice markedly extended survival, likely through caspase-dependent degradation of PML-RARα. | Cell line/in vivo (HL60, NB4, ATRA resistant NB4-R1 cells. HL-60 xenografted tumor mouse model, ATRA-sensitive/resistant transplantable mouse model). | [126] |

| 2-Methyl-naphtho[2,3-b] furan-4,9-dione (FNQ3) | To obtain agents most efficient for cancer cell death with minimal effects for normal cells, FNQ3 was initially identified by Hirai et al. [175]. | FNQ3 induced growth arrest and apoptosis in various human AML (HL-60, NB-4, U937, THP-1) and myeloma cell lines (RPMI-8226, ARH-77, NCI-H929, U266). Among primary AML samples, 11 of 14 showed reduced clonogenic growth. | Cell line/primary blasts (HL-60, NB-4, U937, THP1, RPMI-8226, ARH-77, NCI-H929, U266. 14 primary AML patients). | [176] |

| Benzodithiophenes (NSC656243) | Using ATRA insensitive NB4 cells (NB4-c) and NBT assay, 371 cytostatic agents from National Cancer Institute library were screened. | NSC656243 potentiated ATRA-induced differentiation in ATRA-insensitive NB4-c cells and induced dose- and time-dependent apoptosis in both NB4-c and HL-60 cells. Derivatives NSC656240, NSC656238, and NSC682994 further enhanced differentiation in NB4-c cells (NBT+%, dose in µM: NSC656243, 53, 5–7; NSC656240, 46, 0.05; NSC656238, 50, 0.05; NSC682994, 50, 0.01). | Cell line (NB4, NB4-c, HL-60, MEL cells, HL-60/Bcl-2 and HL-60/neo cells). | [177] |

| ST1346, ST1707 (a novel class of agents with bis-indolic structures (BISINDs) | Screening experiment using NB4 cells to select compounds that enhance the differentiating activity of ATRA | BISINDs augmented ATRA-induced STAT1 activation in APL cells and counteracted ATRA-mediated downregulation of Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK). This JNK activation likely contributes to the enhanced differentiation. Furthermore, ST1346 increased NBT-reducing activity across all examined cell lines. | Cell line (NB4, NB4.306, U937, Kazumi, HL-60, KG1, and PR9 [a U937-derived cell clone expressing PML-RARα upon induction with zinc sulfate] cells). | [178] |

| Oleanane triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid (CDDO) | Triterpenoids and some like ursolic and oleanolic acids are known to be anti-inflammatory and anticarcinogenic. The authors synthesized novel oleanane triterpenoid which has potent biological activities. | The compound promotes differentiation in diverse cell lines, including myeloid leukemia cells, and exhibits growth-inhibitory effects on a range of human tumor cell lines. It also downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, thereby reducing the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). | Cell line (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, 21-MT-1, 21-MT-2, 21-NT, 21-PT, THP-1, U937, HL-60, NB4, AML 193, KG-1, ML-1, NT2/D1, A2058, MDA-MB-468, SW626, AsPc-1, CAPAN-1e). | [179] |

| CDDO-Me, a novel C-28 methyl ester of CDDO. | As CDDO was shown to have potent antiproliferative and differentiating activity, the activity of C-28 methyl ester form of CDDO was Examined. | CDDO-Me induced apoptosis and promoted granulo-monocytic differentiation in HL-60 cells, while inducing monocytic differentiation in primary AML cells. The combination of ATRA with CDDO-Me or the RXR-specific ligand LG100268 further enhanced these effects. | Cell line/primary blasts (HL-60, KG-1, U937, Jurkat, NB4. HL-60–doxorubicin-resistant cells (HL-60-DOX). U937/Bcl-2 and its vector control, U937/pCEP. 4 primary AML and 2 primary CML-BC patients’ samples). | [180] |

| 6-aminonicotinamide, 3-acetylpyridine, Nicotinic acid hydrazide, Nicotinamide, Nicotinic acid, etc. | Niacin related compound | Induce differentiation from morphology, and also loss of non-specific esterase activity. | Cell line (HL-60 cells). | [183] |

5. Repurposed Agents with Unclear Mechanisms of Action

| Repurposed Agents with Unclear Mechanisms of Action, Enhancing ATRA-Induced Differentiation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiation Agent(s) | Characteristics | Results | Model Level | Ref |

| Tamoxifen | Selective estrogen receptor modulator | LG-362B promoted differentiation in both APL Tamoxifen markedly potentiated the differentiation-inducing and growth-suppressive effects of ATRA in NB4 and HT93 APL cell lines, as well as in primary APL cells. | Cell line/primary blasts (HL-60, NB4 and HT93 APL cells. Normal mouse bone marrow cells. One primary APL cells). | [126] |

| Amantadine | An antiviral and anti-Parkinson agent | Amantadine induced monocyte–macrophage-like differentiation in several myeloid leukemia cell lines when combined with suboptimal concentrations of ATRA or 1α,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. | Cell line (HL-60, U937, Kasumi-1 cells). | [188] |

| Metformin | Agent for treating diabetes | Metformin treatment in NB4 APL cells activated the MEK/MAPK pathway, promoting their differentiation. | Cell line (Kasumi-1, SKNO-1, HL-60, KG-1a and NB4 cells). | [189] |

| lithium chloride (LiCl) | Agent used for manic-depressive patients | Lithium led to the enlargement of the total neutrophil mass and neutrophil production. | Primary samples (12 lithium treated patients). | [190] |

| LiCl (5 mM) enhanced ATRA (3 µM)-induced effects in 50% of the patients tested. | Primary blasts (Primary specimens from 13 AML, 6 APL patients). | [191] | ||

| LiCl was more effective than G-CSF. Combinations of ATRA with LiCl resulted in the synergistic differentiation of WEHI-3B D+ myelomonocytic leukemia cells | Cell line (WEHI-3B myelomonocytic leukemia cells). | [192] | ||

| LiCl treatment induced immunophenotypic changes indicative of myeloid differentiation in five patients, and four of them achieved disease stability with no rise in circulating blasts for over four weeks. | Primary blasts (Nine relapsed, refractory AML patients with median age 65 [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,93,94] years were enrolled). | [194] | ||

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2-HG | 2-Hydroxyglutarate |

| 6BT | 6-Benzylthioinosine |

| AICAr | Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamideribonucleoside |

| Akt | ProteinkinaseB |

| AML | Acutemyeloidleukemia |

| APA | Combinationofazacitidine, pioglitazone, and ATRA |

| APL | Acutepromyelocyticleukemia |

| Ara-A | 9-β-D-Arabinofuranosyladenine |

| Ara-C | Cytarabine |

| ATRA | All-transretinoicacid |

| ATO | Arsenictrioxide |

| AZA | 5-Azacitidine |

| Bcl-2 | B-celllymphoma2 |

| CA | Caffeicacid |

| CDK | Cyclin-dependentkinase |

| C/EBP | CCAAT/enhancer-bindingprotein |

| CN-A | CotyleninA |

| CR | Completeremission |

| dCF | 2′-Deoxycoformycin |

| DHFR | Dihydrofolatereductase |

| DHODH | Dihydroorotatedehydrogenase |

| DMDC | 1-(2-Deoxy-2-methylene-β-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)cytidine |

| DMY | Dihydromyricetin |

| DNMT | DNAmethyltransferase |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechingallate |

| EGFR | Epidermalgrowthfactorreceptor |

| ERK | Extracellularsignal-regulatedkinase |

| FLT3 | Fms-liketyrosinekinase3 |

| G-CSF | Granulocytecolony-stimulatingfactor |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophagecolony-stimulatingfactor |

| GSK3β | Glycogensynthasekinase3beta |

| HDAC | Histonedeacetylase |

| IDH | Isocitratedehydrogenase |

| JAK | Januskinase |

| LIC | Leukemia-initiatingcell |

| LSD1 | Lysine-specificdemethylase1 |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activatedproteinkinase |

| MDS | Myelodysplasticsyndrome |

| MDM2 | Murinedoubleminute2 |

| MEK | MAPK/ERKkinase |

| MJ | Methyljasmonate |

| mTOR | Mammaliantargetofrapamycin |

| O-GlcNAc | O-linkedβ-N-acetylglucosamine |

| OGT | O-linkedN-acetylglucosaminetransferase |

| PGZ | Pioglitazone |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol3-kinase |

| PKC | ProteinkinaseC |

| PML | Promyelocyticleukemia |

| PPARγ | Peroxisomeproliferator-activatedreceptorgamma |

| PTEN | Phosphataseandtensinhomolog |

| RARα | Retinoicacidreceptoralpha |

| ROS | Reactiveoxygenspecies |

| SFK | Srcfamilykinase |

| SIK | Salt-induciblekinase |

| STAT | Signaltransducerandactivatoroftranscription |

| SUMO | Smallubiquitin-likemodifier |

| TCN | Triciribine |

| TPT | Topotecan |

| VPA | Valproicacid |

References

- Takahashi, S. Current Understandings of Myeloid Differentiation Inducers in Leukemia Therapy. Acta Haematol. 2021, 144, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S. Kinase Inhibitors and Interferons as Other Myeloid Differentiation Inducers in Leukemia Therapy. Acta Haematol. 2022, 145, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Aziz, A.K. Advances in acute myeloid leukemia differentiation therapy: A critical review. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 215, 115709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottomly, D.; Long, N.; Schultz, A.R.; Kurtz, S.E.; Tognon, C.E.; Johnson, K.; Abel, M.; Agarwal, A.; Avaylon, S.; Benton, E.; et al. Integrative analysis of drug response and clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2022, 40, 850–864e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.F.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Lou, Y.J.; Yang, M.; Xu, J.Y.; Sun, C.H.; Mao, L.P.; Xu, G.X.; Li, L.; et al. Oral arsenic and retinoic acid for high-risk acute promyelocytic leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.F.; Lu, S.Y.; Zhao, X.S.; Qin, Y.Z.; Liu, X.H.; Jia, J.S.; Wang, J.; Gong, L.Z.; Jiang, Q.; Zhao, T.; et al. PML-RARA transcript levels at the end of induction therapy are associated with prognosis in non-high-risk acute promyelocytic leukaemia with all-trans retinoic acid plus arsenic in front-line therapy: Long-term follow-up of a single-centre cohort study. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 195, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.H.; Wu, D.P.; Du, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Ma, J.; Shao, Z.H.; Ren, H.Y.; Hu, J.D.; Xu, K.L.; et al. Oral arsenic plus retinoic acid versus intravenous arsenic plus retinoic acid for non-high-risk acute promyelocytic leukaemia: A non-inferiority, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino, G.; Lo-Coco, F.; Fenu, S.; Travaglini, L.; Finolezzi, E.; Mancini, M.; Nanni, M.; Careddu, A.; Fazi, F.; Padula, F.; et al. Sequential valproic acid/all-trans retinoic acid treatment reprograms differentiation in refractory and high-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 8903–8911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bug, G.; Ritter, M.; Wassmann, B.; Schoch, C.; Heinzel, T.; Schwarz, K.; Romanski, A.; Kramer, O.H.; Kampfmann, M.; Hoelzer, D.; et al. Clinical trial of valproic acid and all-trans retinoic acid in patients with poor-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2005, 104, 2717–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuendgen, A.; Knipp, S.; Fox, F.; Strupp, C.; Hildebrandt, B.; Steidl, C.; Germing, U.; Haas, R.; Gattermann, N. Results of a phase 2 study of valproic acid alone or in combination with all-trans retinoic acid in 75 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Ann. Hematol. 2005, 84, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffoux, E.; Chaibi, P.; Dombret, H.; Degos, L. Valproic acid and all-trans retinoic acid for the treatment of elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2005, 90, 986–988. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Schelker, R.; Klobuch, S.; Zaiss, S.; Troppmann, M.; Rehli, M.; Haferlach, T.; Herr, W.; Reichle, A. Biomodulatory therapy induces complete molecular remission in chemorefractory acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2015, 100, e4–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübbert, M.; Grishina, O.; Schmoor, C.; Schlenk, R.F.; Jost, E.; Crysandt, M.; Heuser, M.; Thol, F.; Salih, H.R.; Schittenhelm, M.M.; et al. Valproate and Retinoic Acid in Combination With Decitabine in Elderly Nonfit Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Results of a Multicenter, Randomized, 2 × 2, Phase II Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffoux, E.; Cras, A.; Recher, C.; Boëlle, P.Y.; de Labarthe, A.; Turlure, P.; Marolleau, J.P.; Reman, O.; Gardin, C.; Victor, M.; et al. Phase 2 clinical trial of 5-azacitidine, valproic acid, and all-trans retinoic acid in patients with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. Oncotarget 2010, 1, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wass, M.; Göllner, S.; Besenbeck, B.; Schlenk, R.F.; Mundmann, P.; Göthert, J.R.; Noppeney, R.; Schliemann, C.; Mikesch, J.-H.; Lenz, G.; et al. A proof of concept phase I/II pilot trial of LSD1 inhibition by tranylcypromine combined with ATRA in refractory/relapsed AML patients not eligible for intensive therapy. Leukemia 2021, 35, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Liao, G.; Yu, B. LSD1/KDM1A inhibitors in clinical trials: Advances and prospects. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayari, M.M.; Santos, H.G.D.; Kwon, D.; Bradley, T.J.; Thomassen, A.; Chen, C.; Dinh, Y.; Perez, A.; Zelent, A.; Morey, L.; et al. Clinical Responsiveness to All-trans Retinoic Acid Is Potentiated by LSD1 Inhibition and Associated with a Quiescent Transcriptome in Myeloid Malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1893–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redner, R.L.; Beumer, J.H.; Kropf, P.; Agha, M.; Boyiadzis, M.; Dorritie, K.; Farah, R.; Hou, J.Z.; Im, A.; Lim, S.H.; et al. A phase-1 study of dasatinib plus all-trans retinoic acid in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2018, 59, 2595–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klobuch, S.; Steinberg, T.; Bruni, E.; Mirbeth, C.; Heilmeier, B.; Ghibelli, L.; Herr, W.; Reichle, A.; Thomas, S. Biomodulatory Treatment With Azacitidine, All-trans Retinoic Acid and Pioglitazone Induces Differentiation of Primary AML Blasts Into Neutrophil Like Cells Capable of ROS Production and Phagocytosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Ren, X.; Huang, K.; Wang, Y.; Liang, X.; Pu, L.; Xiong, S.; et al. The CDK4/6 Inhibitor Palbociclib Synergizes with ATRA to Induce Differentiation in AML. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2024, 23, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novikova, S.; Tolstova, T.; Kurbatov, L.; Farafonova, T.; Tikhonova, O.; Soloveva, N.; Rusanov, A.; Zgoda, V. Systems Biology for Drug Target Discovery in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, L.; Borgne, A.; Mulner, O.; Chong, J.P.J.; Blow, J.J.; Inagaki, N.; Inagaki, M.; Delcros, J.G.; Moulinoux, J.P. Biochemical and cellular effects of roscovitine, a potent and selective inhibitor of the cyclin-dependent kinases cdc2, cdk2 and cdk5. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 243, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Duan, X.; Gao, F.; Yang, M.; Yen, A. Roscovitine enhances all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA)-induced nuclear enrichment of an ensemble of activated signaling molecules and augments ATRA-induced myeloid cell differentiation. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 1017–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Duan, X.; Gao, F.; Yang, M.; Yen, A. Roscovitine enhances All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA)-induced leukemia cell differentiation: Novel effects on signaling molecules for a putative Cdk2 inhibitor. Cell Signal. 2020, 71, 109555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Xiang, S.; Fu, H.; Chen, Y.; Xu, A.; Liu, Y.; Qi, X.; Cao, J.; Zhu, H.; Yang, B.; et al. CDK2 suppression synergizes with all-trans-retinoic acid to overcome the myeloid differentiation blockade of AML cells. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 151, 104545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Xia, L.; Gabrilove, J.; Waxman, S.; Jing, Y. Sorafenib Inhibition of Mcl-1 Accelerates ATRA-Induced Apoptosis in Differentiation-Responsive AML Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.B.; Redner, R.L.; Johnson, D.E. Inhibition of Src family kinases enhances retinoic acid induced gene expression and myeloid differentiation. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 3081–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Weng, X.Q.; Sheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Liang, C.; Cai, X. Dasatinib synergizes with ATRA to trigger granulocytic differentiation in ATRA resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia cell lines via Lyn inhibition-mediated activation of RAF-1/MEK/ERK. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 119, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriyama, N.; Yuan, B.; Hatta, Y.; Takagi, N.; Takei, M. Lyn, a tyrosine kinase closely linked to the differentiation status of primary acute myeloid leukemia blasts, associates with negative regulation of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VD3)-induced HL-60 cells differentiation. Cancer Cell Int. 2016, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congleton, J.; MacDonald, R.; Yen, A. Src inhibitors, PP2 and dasatinib, increase retinoic acid-induced association of Lyn and c-Raf (S259) and enhance MAPK-dependent differentiation of myeloid leukemia cells. Leukemia 2012, 26, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropf, P.L.; Wang, L.; Zang, Y.; Redner, R.L.; Johnson, D.E. Dasatinib promotes ATRA-induced differentiation of AML cells. Leukemia 2010, 24, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.G.; Cheong, H.J.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, S.C.; Lee, N.; Park, H.S.; Won, J.H. Src Family Kinase Inhibitor PP2 Has Different Effects on All-Trans-Retinoic Acid or Arsenic Trioxide-Induced Differentiation of an Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Cell Line. Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 45, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.K.; Noh, E.K.; Yoon, D.J.; Jo, J.C.; Choi, Y.; Koh, S.; Baek, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Min, Y.J.; Kim, H. Radotinib Induces Apoptosis of CD11b+ Cells Differentiated from Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Zhong, L.; Liu, L.; Fang, Y.; Qi, X.; Cao, J.; Yang, B.; He, Q.; Ying, M. Autophagy contributes to dasatinib-induced myeloid differentiation of human acute myeloid leukemia cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 89, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Ding, M.; Weng, X.Q.; Sheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Z.Y.; Cai, X. Combination of enzastaurin and ATRA exerts dose-dependent dual effects on ATRA-resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 906–926. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Y.; Liang, C.; Ding, M.; Weng, X.Q.; Sheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Lu, H.; Cai, X. Enzastaurin enhances ATRA-induced differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2020, 12, 7836–7854. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Weng, X.Q.; Sheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Ding, M.; Cai, X. Staurosporine enhances ATRA-induced granulocytic differentiation in human leukemia U937 cells via the MEK/ERK signaling pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 3072–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.W.; Shen, X.; Long, W.Y.; Xiao, H.; Li, F.-J.; Xing, S.; Xiong, G.L.; Yu, Z.Y.; Cong, Y.W. Salt-inducible kinase inhibition sensitizes human acute myeloid leukemia cells to all-trans retinoic acid-induced differentiation. Int. J. Hematol. 2021, 113, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Ou, Z.; Deng, G.; Li, S.; Su, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Hu, W.; Chen, F. The Translational Landscape Revealed the Sequential Treatment Containing ATRA plus PI3K/AKT Inhibitors as an Efficient Strategy for AML. Ther. Pharm. 2022, 14, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishioka, C.; Ikezoe, T.; Yang, J.; Gery, S.; Koeffler, H.P.; Yokoyama, A. Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling potentiates the effects of all-trans retinoic acid to induce growth arrest and differentiation of human acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 1710–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, L.Y.; Pereira-Martins, D.A.; Weinhäuser, I.; Ortiz, C.; Cândido, L.A.; Lange, A.P.; De Abreu, N.F.; Mendonza, S.E.S.; Wagatsuma, V.M.d.D.; Nascimento, M.C.D.; et al. The Combination of Gefitinib With ATRA and ATO Induces Myeloid Differentiation in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Resistant Cells. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 686445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainey, E.; Wolfromm, A.; Sukkurwala, A.Q.; Micol, J.-B.; Fenaux, P.; Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G. EGFR inhibitors exacerbate differentiation and cell cycle arrest induced by retinoic acid and vitamin D3 in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 2978–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Li, Z.-Y.; Ding, M.; Liang, C.; Weng, X.-Q.; Sheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Cai, X. Trametinib enhances ATRA-induced differentiation in AML cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 2021, 62, 3361–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.S.; Greenblatt, S.M.; Shirley, C.M.; Duffield, A.S.; Bruner, J.K.; Li, L.; Nguyen, B.; Jung, E.; Aplan, P.D.; Ghiaur, G.; et al. All-trans retinoic acid synergizes with FLT3 inhibition to eliminate FLT3/ITD+ leukemia stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Blood 2016, 127, 2867–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, H.E.; Stengel, K.; Pino, J.C.; Johnston, G.; Childress, M.; Gorska, A.E.; Arrate, P.M.; Fuller, L.; Villaume, M.; Fischer, M.A.; et al. Selective Inhibition of JAK1 Primes STAT5-Driven Human Leukemia Cells for ATRA-Induced Differentiation. Target Oncol. 2021, 16, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xian, M.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, B.; Ying, M.; He, Q. The HER2 inhibitor TAK165 Sensitizes Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells to Retinoic Acid-Induced Myeloid Differentiation by activating MEK/ERK mediated RARalpha/STAT1 axis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, D.; Suzukawa, K.; Himeno, S. Arsenic trioxide augments all-trans retinoic acid-induced differentiation of HL-60 cells. Life Sci. 2016, 149, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, H.; Boulanger, M.; Hosseini, M.; Kowalczyk, J.; Zaghdoudi, S.; Salem, T.; Sarry, J.E.; Hicheri, Y.; Cartron, G.; Piechaczyk, M.; et al. Targeting the SUMO Pathway Primes All-trans Retinoic Acid-Induced Differentiation of Nonpromyelocytic Acute Myeloid Leukemias. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 2601–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Shen, M.; Bunaciu, R.P.; Bloom, S.E.; Varner, J.D.; Yen, A. Arsenic trioxide cooperates with all trans retinoic acid to enhance mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and differentiation in PML-RARalpha negative human myeloblastic leukemia cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 2010, 51, 1734–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S. Combination Therapies with Kinase Inhibitors for Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treatment. Hematol. Rep. 2023, 15, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.E. Src family kinases and the MEK/ERK pathway in the regulation of myeloid differentiation and myeloid leukemogenesis. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2008, 48, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourhill, T.; Narendran, A.; Johnston, R.N. Enzastaurin: A lesson in drug development. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 112, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, H.; Kornblau, S.M.; ter Elst, A.; Scherpen, F.J.G.; Qiu, Y.H.; Coombes, K.R.; de Bont, E.S.J.M. Epidermal growth factor receptor is expressed and active in a subset of acute myeloid leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S. Downstream molecular pathways of FLT3 in the pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia: Biology and therapeutic implications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2011, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, C.; Yao, Q.; Gu, X.; Shi, Q.; Yuan, X.; Chu, Q.; Bao, Z.; Lu, J.; Li, L. Evolving cognition of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway: Autoimmune disorders and cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallemand-Breitenbach, V.; Jeanne, M.; Benhenda, S.; Nasr, R.; Lei, M.; Peres, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, J.; Raught, B.; De Thé, H. Arsenic degrades PML or PML-RARalpha through a SUMO-triggered RNF4/ubiquitin-mediated pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossis, G.; Sarry, J.-E.; Kifagi, C.; Ristic, M.; Saland, E.; Vergez, F.; Salem, T.; Boutzen, H.; Baik, H.; Brockly, F.; et al. The ROS/SUMO axis contributes to the response of acute myeloid leukemia cells to chemotherapeutic drugs. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 1815–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriyama, N.; Yuan, B.; Yoshino, Y.; Hatta, Y.; Horikoshi, A.; Aizawa, S.; Takei, M.; Takeuchi, J.; Takagi, N.; Toyoda, H. Enhancement of differentiation induction and upregulation of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins and PU.1 in NB4 cells treated with combination of ATRA and valproic acid. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 44, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, D.N.; O’dOnovan, T.R.; Laursen, K.B.; Orfali, N.; Cahill, M.R.; Mongan, N.P.; Gudas, L.J.; McKenna, S.L. All-Trans-Retinoic Acid Combined With Valproic Acid Can Promote Differentiation in Myeloid Leukemia Cells by an Autophagy Dependent Mechanism. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 848517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, S.; Abdel-Aziz, A.K.; Ceccacci, E.; Pallavicini, I.; Santoro, F.; de Thé, H.; Minucci, S. Co-targeting leukemia-initiating cells and leukemia bulk leads to disease eradication. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1306–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, M.; Moretti, S.; Soilihi, H.; Pallavicini, I.; Peres, L.; Mercurio, C.; Zuffo, R.D.; Minucci, S.; de Thé, H. Valproic acid induces differentiation and transient tumor regression, but spares leukemia-initiating activity in mouse models of APL. Leukemia 2012, 26, 1630–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asou, H.; Verbeek, W.; Williamson, E.; Elstner, E.; Kubota, T.; Kamada, N.; Koeffler, H.P. Growth inhibition of myeloid leukemia cells by troglitazone, a ligand for peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma, and retinoids. Int. J. Oncol. 1999, 15, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagitko-Dorfs, N.; Jiang, Y.; Duque-Afonso, J.; Hiller, J.; Yalcin, A.; Greve, G.; Abdelkarim, M.; Hackanson, B.; Lübbert, M. Epigenetic priming of AML blasts for all-trans retinoic acid-induced differentiation by the HDAC class-I selective inhibitor entinostat. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, H.; Towatari, M.; Hatano, S.; Kitamura, K.; Kiyoi, H.; Kinoshita, T.; Tanimoto, M.; Murate, T.; Kawashima, K.; Saito, H.; et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors are the potent inducer/enhancer of differentiation in acute myeloid leukemia: A new approach to anti-leukemia therapy. Leukemia 1999, 13, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.H.; Weng, L.J.; Fu, S.; Piantadosi, S.; Gore, S.D. Augmentation of phenylbutyrate-induced differentiation of myeloid leukemia cells using all-trans retinoic acid. Leukemia 1999, 13, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, N.J.; Rytting, M.E.; Cortes, J.E. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet 2018, 392, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, N.J.; Konopleva, M.; Kadia, T.M.; Borthakur, G.; Ravandi, F.; DiNardo, C.D.; Daver, N. Advances in the Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: New Drugs and New Challenges. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 506–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutzen, H.; Saland, E.; Larrue, C.; de Toni, F.; Gales, L.; Castelli, F.A.; Cathebas, M.; Zaghdoudi, S.; Stuani, L.; Kaoma, T.; et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutations prime the all-trans retinoic acid myeloid differentiation pathway in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatier, M.; Boet, E.; Zaghdoudi, S.; Guiraud, N.; Hucteau, A.; Polley, N.; Cognet, G.; Saland, E.; Lauture, L.; Farge, T.; et al. Activation of Vitamin D Receptor Pathway Enhances Differentiating Capacity in Acute Myeloid Leukemia with Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Mutations. Cancers 2021, 13, 5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, T.; Chen, W.C.; Göllner, S.; Howell, L.; Jin, L.; Hebestreit, K.; Klein, H.-U.; Popescu, A.C.; Burnett, A.; Mills, K.; et al. Inhibition of the LSD1 (KDM1A) demethylase reactivates the all-trans-retinoic acid differentiation pathway in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, J.; Abou-El-Ardat, K.; Dalic, D.; Kurrle, N.; Maier, A.M.; Mohr, S.; Schütte, J.; Vassen, L.; Greve, G.; Schulz-Fincke, J.; et al. LSD1 inhibition by tranylcypromine derivatives interferes with GFI1-mediated repression of PU.1 target genes and induces differentiation in AML. Leukemia 2019, 33, 1411–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, D.S.; Svechkarev, D.; Souchek, J.J.; Hill, T.K.; Taylor, M.A.; Natarajan, A.; Mohs, A.M. Impact of structurally modifying hyaluronic acid on CD44 interaction. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 8183–8192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coradini, D.; Pellizzaro, C.; Scarlata, I.; Zorzet, S.; Garrovo, C.; Abolafio, G.; Speranza, A.; Fedeli, M.; Cantoni, S.; Sava, G.; et al. A novel retinoic/butyric hyaluronan ester for the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia: Preliminary preclinical results. Leukemia 2006, 20, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennette, K.W. The role of metals in carcinogenesis: Biochemistry and metabolism. Environ. Health Perspect. 1981, 40, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, N.; Zhao, R.; Song, G.; Zhong, W. Selenite reactivates silenced genes by modifying DNA methylation and histones in prostate cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2008, 29, 2175–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olm, E.; Jönsson-Videsäter, K.; Ribera-Cortada, I.; Fernandes, A.P.; Eriksson, L.C.; Lehmann, S.; Rundlöf, A.-K.; Paul, C.; Björnstedt, M. Selenite is a potent cytotoxic agent for human primary AML cells. Cancer Lett. 2009, 282, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Selvam, A.K.; Wallenberg, M.; Ambati, A.; Matolcsy, A.; Magalhaes, I.; Lauter, G.; Björnstedt, M. Selenite promotes all-trans retinoic acid-induced maturation of acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 74686–74700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, D.B.; Kfoury, Y.S.; Mercier, F.E.; Wawer, M.J.; Law, J.M.; Haynes, M.K.; Lewis, T.A.; Schajnovitz, A.; Jain, E.; Lee, D.; et al. Inhibition of Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase Overcomes Differentiation Blockade in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cell 2016, 167, 171–186e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, S.; Merz, C.; Evans, L.; Gradl, S.; Seidel, H.; Friberg, A.; Eheim, A.; Lejeune, P.; Brzezinka, K.; Zimmermann, K.; et al. The novel dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) inhibitor BAY 2402234 triggers differentiation and is effective in the treatment of myeloid malignancies. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2403–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalic, H.; Dembitz, V.; Lukinovic-Skudar, V.; Banfic, H.; Visnjic, D. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside induces differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 2014, 55, 2375–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitz, V.; Lalic, H.; Kodvanj, I.; Tomic, B.; Batinic, J.; Dubravcic, K.; Batinic, D.; Bedalov, A.; Visnjic, D. 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside induces differentiation in a subset of primary acute myeloid leukemia blasts. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Suzuki, S.; Sato-Nagaoka, Y.; Ito, C.; Takahashi, S. Identification of triciribine as a novel myeloid cell differentiation inducer. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wald, D.N.; Vermaat, H.M.; Zang, S.; Lavik, A.; Kang, Z.; Peleg, G.; Gerson, S.L.; Bunting, K.D.; Agarwal, M.L.; Roth, B.L.; et al. Identification of 6-benzylthioinosine as a myeloid leukemia differentiation-inducing compound. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 4369–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Jyotsana, N.; Lai, C.K.; Chaturvedi, A.; Gabdoulline, R.; Görlich, K.; Murphy, C.; Blanchard, J.E.; Ganser, A.; Brown, E.; et al. Pyrimethamine as a Potent and Selective Inhibitor of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Identified by High-throughput Drug Screening. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2016, 16, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Shao, J.; Li, L.; Peng, X.; Chen, M.; Li, G.; Yan, H.; Yang, B.; Luo, P.; He, Q. All-trans retinoic acid synergizes with topotecan to suppress AML cells via promoting RARalpha-mediated DNA damage. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devy, L.; Hollender, P.; Munaut, C.; Colige, A.; Garnotel, R.; Foidart, J.-M.; Noël, A.; Jeannesson, P. Matrix and serine protease expression during leukemic cell differentiation induced by aclacinomycin and all-trans-retinoic acid. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002, 63, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niitsu, N.; Higashihara, M.; Honma, Y. The catalytic DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor ICRF-193 and all-trans retinoic acid cooperatively induce granulocytic differentiation of acute promyelocytic leukemia cells: Candidate drugs for chemo-differentiation therapy against acute promyelocytic leukemia. Exp. Hematol. 2002, 30, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Niitsu, N.; Ishii, Y.; Matsuda, A.; Honma, Y. Induction of differentiation of acute promyelocytic leukemia cells by a cytidine deaminase-resistant analogue of 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine, 1-(2-deoxy-2-methylene-beta-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)cytidine. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Stagno, F.; Guglielmo, P.; Consoli, U.; Inghilterra, G.; Giustolisi, G.M.; Palumbo, G.A.; Giustolisi, R. In vitro apoptotic response of freshly isolated chronic myeloid leukemia cells to all-trans retinoic acid and cytosine arabinoside. Acta Haematol. 2000, 104, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niitsu, N.; Umeda, M.; Honma, Y. Myeloid and monocytoid leukemia cells have different sensitivity to differentiation-inducing activity of deoxyadenosine analogs. Leuk Res. 2000, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niitsu, N.; Umeda, M.; Honma, Y. Induction of differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cells by 2′-deoxycoformycin in combination with 2′-deoxyadenosine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 238, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niitsu, N.; Honma, Y. Adenosine analogs as possible differentiation-inducing agents against acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 1999, 34, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.D.; Eich, M.L.; Varambally, S. Dysregulation of de novo nucleotide biosynthetic pathway enzymes in cancer and targeting opportunities. Cancer Lett. 2020, 470, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembitz, V.; Tomic, B.; Kodvanj, I.; Simon, J.A.; Bedalov, A.; Visnjic, D. The ribonucleoside AICAr induces differentiation of myeloid leukemia by activating the ATR/Chk1 via pyrimidine depletion. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 15257–15270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, H.B.; Meier, T.I.; Geeganage, S.; Fales, K.R.; Thrasher, K.J.; Konicek, S.A.; Spencer, C.D.; Thibodeaux, S.; Foreman, R.T.; Hui, Y.-H.; et al. Characterization of a novel AICARFT inhibitor which potently elevates ZMP and has anti-tumor activity in murine models. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxhaj, G.; Hughes-Hallett, J.; Timson, R.C.; Ilagan, E.; Yuan, M.; Asara, J.M.; Ben-Sahra, I.; Manning, B.D. The mTORC1 Signaling Network Senses Changes in Cellular Purine Nucleotide Levels. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S. Signaling effect, combinations, and clinical applications of triciribine. J. Chemother. 2024, 87, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.C.; Hurlbert, R.B.; Boss, G.R.; Massia, S.P. Inhibition of two enzymes in de novo purine nucleotide synthesis by triciribine phosphate (TCN-P). Biochem. Pharmacol. 1989, 38, 4045–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shantz, G.D.; Smith, C.M.; Fontenelle, L.J.; Lau, H.K.; Henderson, J.F. Inhibition of purine nucleotide metabolism by 6-methylthiopurine ribonucleoside and structurally related compounds. Cancer Res. 1973, 33, 2867–2871. [Google Scholar]

- Abali, E.E.; Skacel, N.E.; Celikkaya, H.; Hsieh, Y.C. Regulation of human dihydrofolate reductase activity and expression. Vitam Horm 2008, 79, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Creemers, G.J.; Lund, B.; Verweij, J. Topoisomerase I inhibitors: Topotecan and irenotecan. Cancer Treat Rev. 1994, 20, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, E.S. MDM2 and BCL-2: To p53 or not to p53? Blood 2023, 141, 1237–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oltersdorf, T.; Elmore, S.W.; Shoemaker, A.R.; Armstrong, R.C.; Augeri, D.J.; Belli, B.A.; Bruncko, M.; Deckwerth, T.L.; Dinges, J.; Hajduk, P.J.; et al. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature 2005, 435, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buschner, G.; Feuerecker, B.; Spinner, S.; Seidl, C.; Essler, M. Differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells with ATRA reduces (18)F-FDG uptake and increases sensitivity towards ABT-737-induced apoptosis. Leuk. Lymphoma 2021, 62, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, M.; Yap, J.L.; Yu, J.; Cione, E.; Fletcher, S.; Kane, M.A. BCL-xL/MCL-1 inhibition and RARgamma antagonism work cooperatively in human HL60 leukemia cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 327, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, D.; Yang, W.; Wang, W.; Hu, Y.; Yang, B.; He, Q. Nutlin-1 strengthened anti-proliferation and differentiation-inducing activity of ATRA in ATRA-treated p-glycoprotein deregulated human myelocytic leukemia cells. Investig. New Drugs 2012, 30, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, Y.; Iriyama, N.; Hatta, Y.; Takei, M. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor potentiates all-trans retinoic acid-induced granulocytic differentiation in acute promyelocytic leukemia cell line HT93A. Cancer Cell Int. 2015, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaizumi, M.; Sato, A.; Koizumi, Y.; Inoue, S.; Suzuki, H.; Suwabe, N.; Yoshinari, M.; Ichinohasama, R.; Endo, K.; Sawai, T. Potentiated maturation with a high proliferating activity of acute promyelocytic leukemia induced in vitro by granulocyte or granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factors in combination with all-trans retinoic acid. Leukemia 1994, 8, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Inazawa, Y.; Saeki, K.; Yuo, A. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-induced terminal maturation of human myeloid cells is specifically associated with up-regulation of receptor-mediated function and CD10 expression. Int. J. Hematol. 2003, 77, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truran, L.; Baines, P.; Hoy, T.; Burnett, A.K. GCSF augments post-progenitor proliferation in serum-free cultures of myelodysplastic marrow while ATRA enhances maturation. Leuk. Res. 1998, 22, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, Y.; Takeda, K. Retinoic acid combined with GM-CSF induces morphological changes with segmented nuclei in human myeloblastic leukemia ML-1 cells. Anticancer Res. 1997, 17, 1951–1955. [Google Scholar]

- Usuki, K.; Kitazume, K.; Endo, M.; Ito, K.; Iki, S.; Urabe, A. Combination therapy with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, all-trans retinoic acid, and low-dose cytotoxic drugs for acute myelogenous leukemia. Intern. Med. 1995, 34, 1186–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsurumi, H.; Tojo, A.; Takahashi, T.; Moriwaki, H.; Asano, S.; Muto, Y. The combined effects of all-trans retinoic acid and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor as a differentiation induction therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia. Intern. Med. 1993, 32, 648–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopf, E.; Plassat, J.L.; Vivat, V.; de The, H.; Chambon, P.; Rochette-Egly, C. Dimerization with retinoid X receptors and phosphorylation modulate the retinoic acid-induced degradation of retinoic acid receptors alpha and gamma through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 33280–33288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, M.; Zhou, X.; Zhong, L.; Lin, N.; Jing, H.; Luo, P.; Yang, X.; Song, H.; Yang, B.; He, Q. Bortezomib sensitizes human acute myeloid leukemia cells to all-trans-retinoic acid-induced differentiation by modifying the RARalpha/STAT1 axis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Ying, M.; Luo, P.; Zhu, D.; Lou, J.; Yang, B.; He, Q. Inhibition of all-trans-retinoic acid-induced proteasome activation potentiates the differentiating effect of retinoid in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Mol. Carcinog. 2011, 50, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasow, A.; Prodromou, N.; Xu, K.; von Lindern, M.; Zelent, A. Retinoids and myelomonocytic growth factors cooperatively activate RARA and induce human myeloid leukemia cell differentiation via MAP kinase pathways. Blood 2005, 105, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosh, W.W.; Quesenberry, P.J. Recombinant human hematopoietic growth factors in the treatment of cytopenias. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1992, 62, S25–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S. A mini-review: The role of glycosylation in acute myeloid leukemia and its potential for treatment. Oncologie 2025, 27, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Liu, J.; Sato, Y.; Miyake, R.; Suzuki, S.; Okitsu, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Isaji, T.; Gu, J.; Takahashi, S. Fucosylation inhibitor 6-alkynylfucose enhances the ATRA-induced differentiation effect on acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 710, 149541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampa-Schittenhelm, K.; Haverkamp, T.; Bonin, M.; Tsintari, V.; Bühring, H.; Haeusser, L.; Blumenstock, G.; Dreher, S.; Ganief, T.; Akmut, F.; et al. Epigenetic activation of O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine transferase overrides the differentiation blockage in acute leukemia. EBioMedicine 2020, 54, 102678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.R.; Hanover, J.A. A little sugar goes a long way: The cell biology of O-GlcNAc. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 208, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liang, T.; Bai, X. O-GlcNAcylation: An important post-translational modification and a potential therapeutic target for cancer therapy. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slawson, C.; Hart, G.W. O-GlcNAc signalling: Implications for cancer cell biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Parker, M.P.; Graw, S.; Novikova, L.V.; Fedosyuk, H.; Fontes, J.D.; Koestler, D.C.; Peterson, K.R.; Slawson, C. O-GlcNAc homeostasis contributes to cell fate decisions during hematopoiesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 1363–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassano, A.; Katsoulidis, E.; Antico, G.; Altman, J.K.; Redig, A.J.; Minucci, S.; Tallman, M.S.; Platanias, L.C. Suppressive effects of statins on acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 4524–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.B.; Li, L.; Nguyen, B.; Brown, P.; Levis, M.; Small, D. Fluvastatin inhibits FLT3 glycosylation in human and murine cells and prolongs survival of mice with FLT3/ITD leukemia. Blood 2012, 120, 3069–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Via, F.I.; Shiraishi, R.N.; Santos, I.; Ferro, K.P.; Salazar-Terreros, M.J.; Junior, G.C.F.; Rego, E.M.; Saad, S.T.O.; Torello, C.O. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate induces apoptosis and differentiation in leukaemia by targeting reactive oxygen species and PIN1. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britschgi, A.; Simon, H.U.; Tobler, A.; Fey, M.F.; Tschan, M.P. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate induces cell death in acute myeloid leukaemia cells and supports all-trans retinoic acid-induced neutrophil differentiation via death-associated protein kinase 2. Br. J. Haematol. 2010, 149, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhong, L.; Chen, M.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, L.; Xu, T.; Xiao, C.; Gan, L.; Shan, Z.; et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate promotes all-trans retinoic acid-induced maturation of acute promyelocytic leukemia cells via PTEN. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 51, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.H.; Zhang, Q.; Shu, G.; Lin, J.C.; Zhao, L.; Liang, X.X.; Yin, L.; Shi, F.; Fu, H.L.; Yuan, Z.X. Dihydromyricetin sensitizes human acute myeloid leukemia cells to retinoic acid-induced myeloid differentiation by activating STAT1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 1702–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, M.C.; Tsang, S.Y.; Chang, L.Y.; Xue, H. Therapeutic potential of wogonin: A naturally occurring flavonoid. CNS Drug Rev. 2005, 11, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, S.; Fas, S.C.; Giaisi, M.; Müller, W.W.; Merling, A.; Gülow, K.; Edler, L.; Krammer, P.H.; Li-Weber, M. Wogonin preferentially kills malignant lymphocytes and suppresses T-cell tumor growth by inducing PLCgamma1- and Ca2+-dependent apoptosis. Blood 2008, 111, 2354–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hui, H.; Yang, H.; Zhao, K.; Qin, Y.; Gu, C.; Wang, X.; Lu, N.; Guo, Q. Wogonoside induces cell cycle arrest and differentiation by affecting expression and subcellular localization of PLSCR1 in AML cells. Blood 2013, 121, 3682–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Guo, Q.; Hui, H. PLSCR1/IP3R1/Ca2+ axis contributes to differentiation of primary AML cells induced by wogonoside. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Duan, Y.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Ke, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.M.; et al. Jiyuan Oridonin A Overcomes Differentiation Blockade in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells With MLL Rearrangements via Multiple Signaling Pathways. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 659720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Gao, C.; Li, F.; Li, X.; Ke, Y.; Liu, H.-M.; Hu, Z.; Wei, L.; et al. Differentiation of imatinib-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia cells with BCR-ABL-T315I mutation induced by Jiyuan Oridonin A. J. Cancer 2023, 14, 1182–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Yang, Y.; Gupta, P.; Wang, A.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Qu, M.; Ke, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.-M.; et al. A Small Molecule Inhibitor, OGP46, Is Effective against Imatinib-Resistant BCR-ABL Mutations via the BCR-ABL/JAK-STAT Pathway. Mol. Ther.-Oncolytics 2020, 18, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, J.; Qu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Ke, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lei, Z.N.; Liu, H.M.; Hu, Z.; et al. OGP46 Induces Differentiation of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells via Different Optimal Signaling Pathways. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 652972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsa, L.; Motafakkerazad, R.; Soheyli, S.T.; Haratian, A.; Kosari-Nasab, M.; Mahdavi, M. Silymarin in combination with ATRA enhances apoptosis induction in human acute promyelocytic NB4 cells. Toxicon 2023, 228, 107127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.M.; Wu, Y.L.; Zhou, M.Y.; Liu, C.X.; Xu, H.Z.; Yan, H.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Sun, H.D.; Chen, G.Q. Pharicin B stabilizes retinoic acid receptor-alpha and presents synergistic differentiation induction with ATRA in myeloid leukemic cells. Blood 2010, 116, 5289–5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, E.; Nishimura, S.; Ohmori, S.; Ozaki, Y.; Satake, M.; Yamazaki, M. Analgesic component of Notopterygium incisum Ting. Chem. Pharm. Bull 1993, 41, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wang, L.; Ran, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; He, H.; Li, L.; Qi, H. Notopterol-induced apoptosis and differentiation in human acute myeloid leukemia HL-60 cells. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2019, 13, 1927–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.Y. Fucoidan as a marine anticancer agent in preclinical development. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 851–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atashrazm, F.; Lowenthal, R.M.; Dickinson, J.L.; Holloway, A.F.; Woods, G.M. Fucoidan enhances the therapeutic potential of arsenic trioxide and all-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia, in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 46028–46041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto-Yamaguchi, Y.; Yamada, K.; Ishii, Y.; Asahi, K.I.; Tomoyasu, S.; Honma, Y. Induction of the monocytic differentiation of myeloid leukaemia cells by cotylenin A, a plant growth regulator. Br. J. Haematol. 2001, 112, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.; Honma, Y.; Asahi, K.I.; Sassa, T.; Hino, K.I.; Tomoyasu, S. Differentiation of human acute myeloid leukaemia cells in primary culture in response to cotylenin A, a plant growth regulator. Br. J. Haematol. 2001, 114, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassa, T.; Tojyo, T.; Munakata, K. Isolation of a new plant growth substance with cytokinin-like activity. Nature 1970, 227, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honma, Y.; Ishii, Y. Differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cells by plant redifferentiation-inducing hormones. Leuk. Lymphoma 2002, 43, 1729–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honma, Y. Cotylenin A--a plant growth regulator as a differentiation-inducing agent against myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2002, 43, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Lau, Y.K.; Xia, W.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Hung, M.C. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor emodin suppresses growth of HER-2/neu-overexpressing breast cancer cells in athymic mice and sensitizes these cells to the inhibitory effect of paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.; Bellon, M.; Nicot, C. Emodin and DHA potently increase arsenic trioxide interferon-alpha-induced cell death of HTLV-I-transformed cells by generation of reactive oxygen species and inhibition of Akt and AP-1. Blood 2007, 109, 1653–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Hu, J.; Zheng, J.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, T.; Lin, Z.; Lin, M. Emodin enhances ATRA-induced differentiation and induces apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 2076–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, Y.; Kasukabe, T.; Kaneko, Y.; Niitsu, N.; Okabe-Kado, J. Ellagic acid, a natural polyphenolic compound, induces apoptosis and potentiates retinoic acid-induced differentiation of human leukemia HL-60 cells. Int. J. Hematol. 2010, 92, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Chakrabarti, A.; Rana, S.; Ramdeo, R.; Roth, B.L.; Agarwal, M.L.; Tse, W.; Agarwal, M.K.; Wald, D.N. Securinine, a myeloid differentiation agent with therapeutic potential for AML. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klochkov, S.; Neganova, M. Unique indolizidine alkaloid securinine is a promising scaffold for the development of neuroprotective and antitumor drugs. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 19185–19195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingrut, O.; Flescher, E. Plant stress hormones suppress the proliferation and induce apoptosis in human cancer cells. Leukemia 2002, 16, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Y.; Kiyota, H.; Sakai, S.; Honma, Y. Induction of differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cells by jasmonates, plant hormones. Leukemia 2004, 18, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsumura, H.; Akimoto, M.; Kiyota, H.; Ishii, Y.; Ishikura, H.; Honma, Y. Gene expression profiles in differentiating leukemia cells induced by methyl jasmonate are similar to those of cytokinins and methyl jasmonate analogs induce the differentiation of human leukemia cells in primary culture. Leukemia 2009, 23, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sarkar, F.H. Multi-targeted therapy of cancer by genistein. Cancer Lett. 2008, 269, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, A.; Kiguchi, K.; Huberman, E. Induction of differentiation and DNA strand breakage in human HL-60 and K-562 leukemia cells by genistein. Cancer Res. 1990, 50, 2618–2624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, Y.; Amran, D.; de Blas, E.; Aller, P. Regulation of genistein-induced differentiation in human acute myeloid leukaemia cells (HL60, NB4) Protein kinase modulation and reactive oxygen species generation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009, 77, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asou, H.; Koshizuka, K.; Kyo, T.; Takata, N.; Kamada, N.; Koeffier, H.P. Resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes, is a new inducer of differentiation in human myeloid leukemias. Int. J. Hematol. 2002, 75, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]