Simple Summary

Sexual challenges are common yet often unaddressed issues for patients undergoing cancer treatment, significantly impacting their overall well-being and relationships. This review aimed to demonstrate how nurses can help with these sensitive concerns, what difficulties they face, and what solutions can improve care. We found that while nurses are crucial in providing support, they often lack specific training, face cultural discomfort, and are limited by hospital policies. Our findings suggest that better education for nurses, clear guidelines, and teamwork among healthcare providers are essential. By making sexual health a regular part of cancer care, we can significantly enhance the quality of life for cancer survivors and ensure a more complete approach to their recovery. This work provides valuable guidance for various healthcare professionals to support cancer patients.

Abstract

Sexual dysfunction affects an estimated 50–70% of cancer survivors but remains underrecognized and undertreated, impacting quality of life and emotional well-being. This narrative review involves a comprehensive search of PubMed/MEDLINE, CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect for English-language publications (January 2010–May 2025), using combined MeSH and free-text terms for ‘sexual health’, ‘cancer’, ‘nursing’, ‘roles of nurses’, ‘immunotherapy’, ‘targeted therapy’, ‘sexual health’, ‘sexual dysfunction’, ‘vaginal dryness’, ‘genitourinary syndrome of menopause’, ‘sexual desire’, ‘body image’, ‘erectile dysfunction’, ‘climacturia’, ‘ejaculatory disorders’, ‘dyspareunia’, and ‘oncology’. We used the IMRAD (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) approach to identify 1245 records and screen titles and abstracts. Fifty studies ultimately met the inclusion criteria (original research, reviews, and clinical guidelines on oncology nursing and sexual health). Results: All the treatments contributed to reduced libido, erectile dysfunction, dyspareunia, and body image concerns, with a prevalence of 57.5% across genders. Oncology nurses can provide sex education and counseling. Barriers (limited training, cultural stigma, and the absence of protocols) hinder effective intervention. Addressing these issues through sexual health curricula, formal referral systems, and policy reforms can enhance nursing care. Future research should assess the impact of targeted nurse education and the institutional integration of sexual health into cancer care.

1. Introduction

Sexuality is recognized as an essential and natural part of everyone’s life, regardless of age or physical condition [1], and is considered a central aspect of healthcare [2]. The harmful impacts of cancer and its treatments on sexuality are well known [3,4,5,6]. Patients with cancer may experience a range of sexual health challenges, including decreased libido, negative body image, vaginal dryness, genital hypoesthesia, negative body image, pain during sexual intercourse, and difficulty achieving orgasm [7,8].

The prevalence of this problem is very high. For example, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of women with cancer revealed that up to 66% experienced sexual problems, with rates ranging from 58% for colorectal cancer to 55–89% for breast and gynecological cancers [9]. Additionally, 77.5–88.7% of breast cancer patients in China experience sexual health problems [10]. Furthermore, Proctor et al. reported that 57.5% of cancer survivors reported scores indicative of sexual dysfunction, with a similar prevalence observed among both men and women [11]. The WHO recommends patient-centered sexual healthcare, which delivers proper education together with counseling and medical support to individuals [12]. There is a lack of standardized protocols for incorporating sexual health education into routine cancer care practices in many institutions [13].

Sexual problems significantly affect patients’ physical and emotional well-being and quality of life and even lead to marital breakdown and suicide during the long cancer journey [14,15,16]. Sexual dysfunction is a common issue among cancer patients and has a significant effect on their overall well-being. However, research shows that it is frequently overlooked and rarely addressed in clinical settings [17,18]. Many patients do not actively seek medical support for sexual health concerns. For example, a study in mainland China revealed that although 42% of women with breast cancer recognized the value of receiving sexual health information from oncology professionals, 76% had never consulted healthcare providers about these issues [18]. Instead, they often turn to friends, peers, or online sources, which may lack reliability or effectiveness [19]. In clinical practice, healthcare professionals such as oncologists and nurses tend to prioritize treatment, rehabilitation, nutrition, and symptom management while often neglecting sexual health [20].

Research into nurses’ perspectives on addressing patients’ sexual health indicates that systemic challenges within the biomedical model of care hinder adequate attention to this issue. These challenges include short appointment times, insufficient training, and unclear professional responsibilities [21]. Additionally, nurses often frame sexual health in purely functional terms, leading to insufficient screening, communication, and interventions related to sexual issues [22]. Therefore, this narrative review seeks to examine existing research on the role of nurses in recognizing, addressing, and supporting sexual dysfunction in cancer patients.

2. Materials and Methods

This narrative review aimed to explore the roles of nurses in addressing sexual dysfunction among oncology patients. A comprehensive literature search was conducted across five major academic databases, namely, PubMed, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect, spanning the period from January 2010 to May 2025.

To ensure inclusivity and depth in the search strategy, Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to combine a broad set of keywords. These included sexual health, cancer, nursing, nursing roles, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, sexual dysfunction, vaginal dryness, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, sexual desire, body image, erectile dysfunction, climacturia, ejaculatory disorders, dyspareunia, and oncology.

A wide range of publication types was considered to capture diverse perspectives and insights. These included original research articles, review papers, case reports, randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and surveys. However, the primary focus remained on original research studies that specifically addressed the role of nurses in managing sexual dysfunction in cancer patients.

Explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to refine the scope of the review. Articles were included if they were published in English and if they directly discussed nursing interventions or roles related to sexual dysfunction in oncology populations. The exclusion criteria were as follows:

- Non-English publications;

- Conference abstracts and commentaries;

- Studies not directly addressing the core topic;

- Duplicate articles.

The initial search yielded 1245 records. After 235 duplicates were removed, 1010 titles and abstracts were screened. On the basis of the eligibility criteria, 50 articles were ultimately selected for inclusion in the final review. Discrepancies in article selection between the two lead reviewers (OA and SA) were resolved through consultation with a third reviewer (PT), maintaining the rigor and objectivity of the review process.

For all the selected studies, the following relevant data were systematically extracted: study aims, sample size and characteristics, geographical location, data collection and analysis methods, and key findings. To ensure the inclusion of the most recent literature, alerts were set up in the databases to capture newly published relevant studies during the review period.

A thematic synthesis and the IMRAD (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) approach [23] were employed to categorize and interpret the data, enabling the identification of recurring themes, current challenges, and emerging trends in the nursing management of sexual dysfunction among cancer patients. Additionally, backward citation tracking (snowballing) was employed by reviewing the reference lists of relevant articles, helping to uncover additional studies that may have been missed in the original search.

The insights gained through this comprehensive review were critically evaluated and integrated into the main body of the manuscript, providing both a broad overview and a detailed interpretation of the current evidence landscape on this important topic.

3. Results

A total of 50 studies met the inclusion criteria and were reviewed. The findings are organized into five thematic areas: (1) prevalence and impact of sexual dysfunction in cancer patients, (2) psychological and social impact of sexual dysfunction, (3) barriers to addressing sexual dysfunction in cancer care, (4) interventions for managing sexual dysfunction in cancer patients, and (5) nurses’ attitudes and beliefs about sexual health. Table 1 and Figure 1 provide a consolidated summary of these themes, highlighting key nursing-related interventions and barriers identified in each area.

Table 1.

Thematic summary.

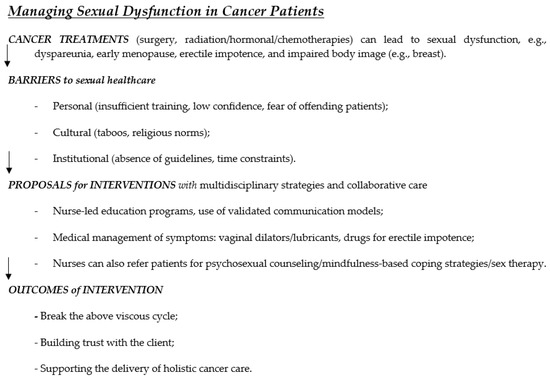

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework summarizes barriers, interventions, and outcomes related to nursing care in individuals with sexual dysfunction.

3.1. Prevalence and Impact of Sexual Dysfunction in Cancer Patients

A detailed summary of the prevalence of sexual dysfunction, affected populations, and associated symptoms across different cancer types is provided in Table 2. In 2022, there were an estimated 20 million new cancer cases and 9.7 million cancer-related deaths globally [46]. While survival rates for many cancers have improved, the long-term consequences of cancer treatments, including sexual dysfunction, remain poorly understood [46]. Studies suggest that cancer survivors often experience long-term difficulties with intimacy, body image, and relationship satisfaction due to sexual dysfunction [46]. Despite the recognition of sexuality as a core component of quality of life, sexual health interventions remain inconsistent across healthcare systems worldwide [47]. The WHO advocated integrating sexual health assessments into cancer survivorship programs to ensure that patients receive comprehensive support that addresses both physical and psychological well-being [48].

The prevalence of sexual dysfunction among cancer patients depends on their specific cancer diagnosis; the treatments they have received; and personal health factors such as age, sex, and pre-existing medical conditions [49]. In addition to direct physical symptoms, sexual dysfunction has also had a profound psychological effect on survivors. Physical changes and psychosocial challenges often lead to anxiety, depression, and self-consciousness, causing a loss of confidence and avoidance of intimacy [50,51]. However, survivors typically receive minimal information or support for managing these sexual side effects, resulting in prolonged distress and a diminished quality of life [28,29]. This lack of guidance exacerbates their difficulties, further reducing relationship satisfaction and negatively impacting mental health outcomes [31]. Despite how common and impactful these issues are, many patients remain reluctant to seek professional help for sexual dysfunction [24,25]. Feelings of embarrassment, stigma, or the assumption that sexual health is not a priority in cancer often discourage open discussion of these problems. Moreover, healthcare providers frequently lack the training, confidence, and institutional support to address sexual issues proactively in oncology practice [52,53]. Together, these factors create a significant gap in care delivery in regard to managing the sexual health of cancer survivors. Closing this gap requires a coordinated, multidisciplinary approach.

Experts advocate implementing routine sexual health assessment as part of cancer follow-up and providing healthcare professionals with dedicated training and resources to manage cancer-related sexual problems, thereby making sexual well-being an integral component of standard survivorship care [52,53]. By ensuring that sexual health is fully integrated into survivorship programs, healthcare systems can better support the long-term quality of life of cancer survivors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the prevalence of sexual dysfunction among cancer patients, broken down by cancer type and gender.

Table 2.

Summary of the prevalence of sexual dysfunction among cancer patients, broken down by cancer type and gender.

| References | Cancer | Gender | Reported Prevalence | Common Manifestations/Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [26,54,55,56] | Breast | F | 16–100% (majority 50–75%) | Sexual difficulty, sexual pain, altered sexual self-image, reduced desire, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia |

| [27,28,56,57] | Gynecologic | F | 30–100% | Vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, loss of sensation, decreased libido, hot flashes, difficulty achieving orgasm, and painful intercourse |

| [56,58] | Rectal (surgery) | F, M | 19–62% (most ~60%) | Sexual dysfunction, body image concerns (stomas), and relationship issues. |

| [41,42,56] | Prostate | M | 40–100% | Erectile dysfunction, loss of desire, problems reaching orgasm |

| [59] | Childhood cancer | F, M | ~1/3 overall, ~½ with 1+ problem, 30% with 2+ problems | Difficulties relaxing/enjoying sex/becoming sexually aroused/achieving orgasm, erection difficulties (men), altered body image, fertility concerns |

| [60,61] | Hematologic (e.g., lymphoma) | F, M | 54% decreased activity, 41% decreased interest | Decreased sexual activity, decreased sexual interest |

| [56] | Lung | F, M | ~50% loss of libido (overall), ~40% decrease in sexual activity in F) | Loss of libido, decrease in sexual activity |

| [56] | Head and neck | F, M | 24–100% negative impact | Negative impact on sexuality |

F: female; M: male.

3.2. Psychological and Social Impact of Sexual Dysfunction

3.2.1. Impact on Partners

Cancer-related sexual dysfunction affects not only patients but also their partners. Multiple studies have reported that partners often experience significant emotional distress, loneliness, and anxiety as they attempt to support their loved one through cancer and its sexual health challenges [29,62]. These partners frequently face a dual burden: concerns for the patient’s well-being and the strain of unmet intimacy needs. Qualitative evidence indicates that male partners of women with cancer, for example, describe feelings of isolation and a profoundly altered sexual relationship, underscoring the partner’s vulnerability in this context [29]. These findings highlight the need for partner-inclusive support, as addressing a couple’s needs (not just patients) is crucial to mitigating the psychosocial toll on partners and maintaining healthy relationship dynamics [29,62].

3.2.2. Psychological Consequences

Untreated individuals with sexual dysfunction can severely undermine the mental health of cancer survivors. Studies have linked sexual problems with elevated levels of psychological distress, notably increased anxiety, depressive symptoms, and reduced self-esteem, among cancer patients [32,33]. As sexual function declines or side effects (e.g., body image changes, pain) emerge, patients often report feeling a diminished sense of self and femininity/masculinity, which can lead to social withdrawal and isolation [32,33]. These psychological consequences are not isolated findings; instead, they appear consistently across diverse cancer populations. The emotional burden of sexual dysfunction is profound and pervasive, suggesting that survivors require not only medical treatment but also proactive psychosocial support to address issues such as fear, frustration, and loss of identity that accompany sexual health changes.

3.2.3. Relational Strains

Sexual dysfunction frequently places strain on intimate relationships. Research indicates that a decline in sexual intimacy and satisfaction can spark frustration, miscommunication, and conflict between partners, thereby eroding overall relationship quality [24,30]. In particular, couples who avoid discussing sexual issues tend to experience greater marital dissatisfaction. Communication about sexual health is often lacking, which exacerbates misunderstanding and emotional distancing [24,30]. Over time, this pattern of poor communication and unmet needs can lead to serious relational consequences. Some studies have documented cases of deteriorating partners’ relationships or even separation linked to unaddressed sexual problems in survivorship [20,30]. Conversely, couples who manage to maintain an honest dialog and seek help for sexual concerns typically fare better, highlighting communication as a key moderating factor. The literature, therefore, emphasizes that fostering healthy communication and providing counseling for couples is essential to prevent sexual dysfunction from translating into a long-term relational breakdown.

3.2.4. Coping Mechanisms

Despite these challenges, sexuality remains fundamental to many patients’ quality of life and identity [31]. Survivors and their partners employ various coping mechanisms to navigate the sexual changes imposed by cancer and its treatment. Some individuals adopt personal coping strategies, such as mindfulness and other stress reduction techniques, which have been associated with lower distress and better emotional adjustment in the face of cancer-related sexual problems [61]. Engaging in psychosocial support, such as joining support groups or couples’ therapy, is another coping avenue that can help normalize conversations about sexual health and reduce feelings of isolation. In addition, experts underscore that effective coping often requires external intervention: comprehensive strategies that address both the physical and psychological aspects of sexuality are advocated as best practices [63,64]. Integrative intervention (combining medical management of symptoms with counseling or sex therapy) has been recommended to bolster patients’ and partners’ coping capacity, enabling them to adapt to sexual changes while preserving emotional intimacy [63,64].

Across the reviewed studies, sexual dysfunction in cancer patients has emerged as a multidimensional problem with consistently observed psychological and social ramifications. Numerous publications spanning different cancer types and cultural contexts document the same core issues: heightened emotional distress and interpersonal difficulties resulting from untreated sexual health concerns [24,32,33]. Notably, earlier works draw attention to the prevalence and seriousness of these psychological impacts (for instance, raising awareness that sexuality should not be overlooked even in life–threatening illnesses) [33]. More recent research has shifted toward identifying protective factors and solutions, such as mindfulness-based coping and holistic intervention programs, reflecting a growing focus on mitigation rather than merely describing the problem [61,63]. This trend signifies an important evolution in the literature: from recognizing that sexual dysfunction profoundly affects patients and their partners to actively exploring ways to buffer its impact. Collectively, the evidence underscores that integrating psychosocial support into sexual health is essential for improving cancer survivors’ quality of life and maintaining healthy relationships in survivorship [63,64].

3.3. Barriers to Addressing Sexual Dysfunction in Cancer Care

Despite growing awareness of the importance of sexual well-being in cancer survivorship, multiple barriers continue to hinder its integration into oncology nursing care. These challenges arise at various levels, including personal discomfort and limited communication skills among nurses [29,34,35], cultural and religious taboos that discourage open dialog [36,65], institutional constraints such as the absence of protocols and time pressure [24,30,38,39,40,66], and patient-related factors such as embarrassment or uncertainty about discussing sexual concerns [24,62,65,67]. As summarized in Table 3, these barriers interact to create systemic silence around sexual dysfunction, limiting nurses’ ability to address this critical aspect of holistic cancer care.

Table 3.

Summary description of barriers to addressing sexual dysfunction.

3.4. Interventions for Managing Sexual Dysfunction in Cancer Patients—Training Programs to Build the Trust of Patients and Achieve Holistic Cancer Care

Oncology nurses play a pivotal role in delivering targeted interventions that span educational, pharmacological, psychosocial, and multidisciplinary strategies. Evidence supports nurse-led sexual health education programs, the use of validated communication models, psychosexual counseling, pharmacologic therapies, digital programs, and collaborative care as essential components of a holistic treatment approach [7,30,42,62,73,74,75]. This intervention, summarized in Table 4, has demonstrated effectiveness in improving sexual health outcomes, increasing patients’ satisfaction, and enhancing the confidence and competence of nurses in addressing this sensitive topic.

Table 4.

Summary descriptions of interventions for managing sexual dysfunction in cancer patients.

3.5. How to Deal with Attitudes and Beliefs of Nurses About Sexual Health

3.5.1. Personal Beliefs and Knowledge Gaps

Attitudes of nurses toward sexuality significantly shape their willingness and ability to initiate sexual health discussions with cancer patients. Many nurses perceive sexuality as a private matter and express discomfort during clinical interaction, fearing that it may offend patients or be considered unprofessional [35,73]. This discomfort often stems from a lack of formal academic preparation and limited clinical exposure to sexual health topics [34,45]. For example, Jordanian students have reported feeling unprepared to address sensitive issues such as the sexual needs of terminally ill patients [59]. Instead, they often rely on informal knowledge, which may not be sufficient to manage the complexities of cancer-related sexual dysfunction. This emphasizes the need to integrate structured sexual health content into nursing curricula and continuous professional development programs [79].

3.5.2. Culture and Religious Influences

In many conservative societies, sexuality remains a taboo topic, and healthcare providers, especially nurses, may avoid discussing it to conform to social expectations [37,50,69]. These cultural constraints can blur the boundaries between professional responsibilities and personal values, making it difficult for nurses to provide unbiased patient-centered care [65,70]. Additionally, patients themselves may feel too embarrassed to initiate such a discussion, instead expecting the healthcare provider to lead this conversation [35,66]. This dynamic often leads to mutual avoidance of sexual health discussion. Cultural and religious influences have a profound impact on both nurses and patients. Overcoming this requires fostering an environment that respects cultural sensitivities while promoting open, professional communication about sexuality.

3.5.3. Experience, Gender, and Communication Challenges

Nurses with more experience in oncology or palliative care are more likely to feel comfortable discussing sexual dysfunction with patients [62,67]. In contrast, novice nurses often avoid this discussion due to a lack of confidence; moreover, gender dynamics further complicate communication. Nurses may feel uneasy when addressing sexual issues with patients of the opposite sex, particularly in a traditional cultural context where such interactions are considered inappropriate [39]. This discomfort intensifies when institutional policies do not support sexual health as a routine component of care. Experience plays a protective role in fostering nurse confidence, but institutional support and cultural adaptation are equally necessary to overcome gender-based communication barriers.

3.5.4. Institutional Roles and Professional Development

When institutions provide clear polices, a supportive environment, and professional development opportunities focused on sexual health, nurses become more proactive in addressing these concerns [24,30,31]. Interventions such as role-playing exercises, structured communication training, and continuing education workshops have been shown to increase nurses’ comfort and perceived competence in this area [73,80]. Institutional initiatives and professional development programs are effective strategies for transforming a hesitant attitude into proactive sexual health engagement. Structured support not only improves clinical confidence but also ensures that patients receive holistic cancer care that includes their sexual well-being.

The literature reveals that while oncology nurses understand the importance of sexual health, many feel unequipped in managing related discussions because of personal discomfort, cultural influences, a lack of education, and institutional neglect. Bridging this gap requires multilevel approaches, integrating sexual health in nursing education, promoting cultural competence, offering experiential training, and embedding sexual health into routine oncology care guidelines.

3.5.5. Global Effort in Oncology Sexual Health Education in Recent Years

There has been increasing global recognition of the need to improve sexual healthcare within oncology services. Academic institutions and healthcare systems in North America, in particular, have developed structured educational programs targeting oncology providers.

In Canada, the trueNTH (true North sexual health and rehabilitation e-training) program has been implemented to increase the competencies of prostate cancer care providers. A multicenter evaluation demonstrated significant improvement in participants’ sexual health knowledge and communication self-efficacy, with almost all participants reporting high satisfaction with the program [81]. Similarly, in Alberta, a dedicated oncology sexual health clinic received over 130 patient referrals in two years, identifying diagnoses of sexual dysfunction in 100% of female patients and 80% of male patients [82]. Ms. Anne Katz, based in Manitoba, should be applauded for her longstanding contributions to sexual health [83]. The Princess Margaret Cancer Center in Toronto has developed hybrid in-person and virtual sexual health services, expanding access to specialized care for a broader patient population [83].

In the United States, the Fox Chase Cancer Center launched the iSHARE (improving Sexual Health and Augmenting Relationships through Education) intervention, which focused on enhancing the ability of breast cancer clinicians to discuss sexual health interventions, leading to increased clinician confidence and sustained patient satisfaction [43].

Internationally, the 2024 summit organized by the scientific network on female sexual health and cancer exemplified a growing effort to promote interdisciplinary education and collaborative models of care [68]. These global initiatives provide compelling evidence that structured education and clinical services significantly enhance sexual health outcomes in oncology.

4. Discussion

In summary, this narrative review highlights that sexual dysfunction is common among cancer patients and profoundly impacts their physical health and psychological and relational well-being. Sexual side effects of cancer and its treatment (e.g., erectile dysfunction, vaginal dryness, and dyspareunia) often lead to a loss of libido, body-image concerns, and strains on intimacy [7,8,58]. Patients report high levels of anxiety and depression associated with unmet sexual needs [11,84]. Significantly, sexual health interventions (e.g., counseling, education) can ameliorate these effects. Studies have shown that targeted sexual health information reduces patients’ anxiety and improves their satisfaction and quality of life [84,85]. The review also underscores the pivotal role of oncology nurses. Nurse-led interventions (using models such as PLISSIT and BETTER) enable sensitive discussion and management of sexual concerns [46,48]. For example, structured programs for nurses have been shown to improve knowledge, confidence, and communication skills [73,86]. Canadian initiatives such as trueNTH e-training have yielded significant gains in provider knowledge and self-efficacy (with 98% satisfaction), effectively preparing nurses to support the sexual health of prostate cancer patients [71]. These interventions align with clinical guidelines: both the ASCO and the NCCN now recommend routine screening for sexual problems and timely referral for specialist care [5,34]. However, multiple barriers prevent the delivery of effective care. Across settings, nurses report a lack of knowledge and training as a primary obstacle [30,38]. Many nurses feel embarrassed or ill prepared; for example, 85% of Belgian oncology nurses and 70% of U.S. nurses in separate studies admitted to discomfort when discussing sexual issues [62,86]. Time constraints and systemic factors (no private space or protocols) are common hurdles [1,87]. Cultural and social taboos further compound these barriers. In conservative societies (e.g., the Middle East, China, and parts of Africa), discussing sexuality is considered shameful, thus discouraging both patients and providers from approaching the subject [49,77]. In Iran or Africa, women with breast cancer, for example, often feel profoundly shameful due to religious and familial norms, leading them to hide sexual problems [27,54]. Even among Western–trained nurses, cultural assumptions (e.g., patients must be grateful to be alive and not need sex) can inhibit discussion [12,26].

4.1. Comparisons with the Literature

These findings corroborate the findings of international nursing studies. Global surveys find that only a minority of oncology clinicians regularly address sexual health; for example, in a Latin American study, only ~10% of physicians felt adequately prepared to manage sexual issues, and ~30% rarely broached the topic [79]. The education gap noted by this review aligns with conclusions from systematic analyses: nurses worldwide recognize sexual health as important, but they report inadequate curricula and on-the-job training [1,24,25]. Recent evidence from the past few years further reinforces these points. Concept mapping in Hong Kong highlighted the need for culturally adapted care models (an extended PLISSIT) to fit the local practice environment [52]. The current adult survivorship guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network of the United States (NCCN) in 2024 explicitly advocate routine sexual function screening and multidisciplinary referral, reflecting an international shift toward the integration of sexual rehabilitation in cancer [5,34]. Recent oncology nursing studies have reinforced the notion that targeted interventions can make a significant difference. For example, a scoping review revealed that a brief active–learning workshop (e.g., role-play using PLISSIT scenarios) significantly improved nurses’ communication comfort and knowledge [1,73,86]. Novel e-learning modules (such as those for adolescent/young adult cancer patients) have been shown to increase awareness of reproductive and sexual health issues among oncology staff [53,57]. Notably, the current review’s Middle East context aligns with new data: a 2025 Jordanian survey reported similar barriers (time, training, and culture) and called for system-level educational reforms [1]. Conversely, research from countries with dedicated sexual health clinics (e.g., Canada’s multidisciplinary clinics) suggests that nurse involvement in such teams leads to more diagnoses and interventions for dysfunction, again supporting the central role of nursing [71,88]. Overall, these additional studies corroborate our narrative review findings and highlight growing global momentum toward addressing cancer-related sexual dysfunction as a standard component of care. This review adds to the current literature in a timely manner by summarizing current information and discussing practical solutions to the growing global problem, as more patients survive initial cancer treatment to address posttreatment sexual health complications.

4.2. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Education

Given these insights, several practical implications emerge. Clinically, oncology nurses should be empowered to initiate sexual health conversations routinely. Models such as the 5 A’s (Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist, Arrange) and structured frameworks (PLISSIT/BETTER) provide practical guides for nurses to normalize discussions and offer basic interventions [46,47,89].

Nurses and nurse practitioners can help mitigate physical side effects through anticipatory guidance—for example, by recommending lubricants, topical vaginal estrogen creams, vaginal dilators, and pelvic floor exercises. They can also connect patients to appropriate specialists for more complex issues, such as sex therapists, fertility counselors, and urologists [80,90]. For instance, nurses can collaborate with other team members, including family physicians and pharmacists, to select the most suitable phosphodiesterase inhibitor for an individual patient, taking into account cardiac comorbidities and lifestyle factors. In general, sildenafil acts more quickly but has a shorter duration of effect compared to tadalafil.

Additionally, nurses can refer patients to plastic surgeons for breast or testicular prostheses. Some men may experience distress following orchiectomy, and the insertion of a testicular prosthesis comparable in size to the contralateral testicle can significantly improve body image.

The evidence suggests that even brief interventions by nurses providing permission, education, and simple suggestions can significantly improve sexual function outcomes (up to 70% of patients can return to baseline with intervention [7,66,91]). Thus, oncology units should allocate time and privacy for these assessments [86].

In terms of policy, institutions and professional organizations must prioritize sexual health. Cancer care guidelines should formally include sexual function as a survivorship quality metric. For example, the NCCN now lists “sexual health” under long-term effects in its survivorship guidelines [5,34]. Hospitals could adopt standardized sexual history checklists in electronic records and track sexual health referral rates as a quality indicator [71]. Reimbursement and scheduling policies should recognize sexual counseling as part of patients’ care. In culturally conservative contexts, policy and administration can facilitate gender-sensitive care (e.g., ensuring the availability of female providers for intimate issues) and provide private settings for discussions.

National health bodies might consider public education campaigns to destigmatize post-treatment sexual issues, as in some Western countries [49,77]. For nursing education, curricula must be revamped. Both pre-licensuring and continuing education programs should incorporate content related to sexual health, anatomy, communication skills, psychosocial aspects, and cultural competence. Simulation and role play (which nurses find highly effective) can prepare nurses to handle these sensitive topics [28,73]. Promising training programs, such as ENRICH (Educating Nurses about Reproductive Issues in Cancer Healthcare, a web-based program on fertility/sexuality training for pediatric oncology nurses), should be expanded to all oncology specialties [57,71]. Academic nursing programs in conservative societies should emphasize that discussing sexuality is integral to holistic cancer care and teaching students to use neutral, validating language. Professional development initiatives (workshops, online modules) are needed to close the current knowledge gap. One review explicitly recommended the creation of oncology nurse training programs to improve attitudes and skills related to sexual health [29,42]. Collectively, these steps can transform the culture of care so that sexual well-being is routinely addressed.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

This narrative review offers a broad synthesis of nursing roles in sexual dysfunction, drawing on diverse sources across cultures and practice settings. Its strengths include integrating recent evidence (e.g., studies from 2024 to 2025) and highlighting underrecognized factors (such as cultural taboos in conservative societies) [1,77]. Focusing on nursing perspectives, this review fills a gap left by many reviews, mostly written for medical doctors [5,53]. The authors’ experiences in the Middle East and China provide valuable insights into taboo barriers. The reference section includes the most important recent studies, and this review is poised to provide valuable guidance for clinicians, nurses, and researchers.

As a narrative (rather than systematic) review, it is subject to specific limitations. Unlike a systematic review, the search strategy may not have been comprehensive; narrative syntheses do not require appraisal. Important studies might have been missed, and the selection of literature can reflect author bias [25,55]. Additionally, without a standardized methodology, reproducibility may be limited. The review mentions primarily English-language and peer-reviewed sources, potentially omitting the other relevant literature or non-English research (e.g., local studies in Asia/Africa) [29,53]. Some of the studies suffer from cultural inhomogeneity, a lack of longitudinal studies, and/or poor methodological quality. Finally, without a meta-analysis, the review provides only a qualitative conclusion regarding different settings in low- versus high-income countries and different cultures. Table 5 summarizes this perspective. Thus, the findings should be interpreted as reflective insights grounded in expert synthesis rather than conclusive empirical evidence.

Table 5.

Comparative overview of how nursing roles in addressing sexual dysfunction among oncology patients differ between high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries.

4.4. Recommendations and Future Directions for Research

Future research should evaluate and refine specific nursing interventions to increase their effectiveness. Randomized trials or controlled studies could test the impact of nursing-led sexual counseling on patient outcomes [46,47]. Comparative research should identify which educational methods (e.g., in-person workshops vs. online modules) are most effective in improving nurses’ competence [73,86]. Culturally tailored models deserve study, for example, by assessing interventions that respect social norms in Middle Eastern or African contexts [49,77]. Research gaps include male sexuality (most studies focus on women) and underserved groups, such as low-income or LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning) patients [7,87]. Health services research could explore how institutional changes (e.g., establishing oncology–sexuality clinics) impact the quality of care [71,88]. Education and training initiatives must be expanded. Oncology units should implement routine sexual health training for all healthcare staff, with refresher sessions to maintain skills [52,57].

5. Conclusions

Empowering nurses through structured education, standardized guidelines, and open communication strategies is essential for improving patient outcomes. Addressing sexual dysfunction as a routine aspect of cancer care will enhance survivors’ quality of life and foster a more holistic approach to oncology treatment.

This research was conducted by a team of researchers with origins in the Middle East and China, both of whom represent conservative traditions and diverse religious backgrounds. This concise overview, which is rich in detailed references and clinical pearls, offers a unique and highly educational resource for healthcare professionals across multiple disciplines, such as nurses, physicians, social workers, psychologists, music therapists, sex therapists, and chaplains. It therefore has broad clinical implications, and practical suggestions will greatly benefit cancer patients and their providers from different disciplines.

Author Contributions

O.A. and S.A.-G.: conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation. O.A., S.A.-G., E.Y., and P.T.: resources, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review, and editing. All the authors, including K.J., K.W., and E.Y., critique the manuscript drafts. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5 A’s | Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist, Arrange |

| BETTER | B: bringing up the topic. E: Explain that you are concerned with all aspects of patients’ lives. T: Tells patients that sexual dysfunction is common. T: Timing might not be right now, but you are open to future discussion. E: Educate patients about sexual side effects. R: Record the conversation in the medical records |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

| ENRICH | Educating Nurses about Reproductive Issues in Cancer Healthcare |

| IMRAD | Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion |

| LGBTQ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| PLISSIT | P: Permission. LI: Limited Information. SS: Specific Suggestions. IT: Intensive Therapy. |

References

- Alqaisi, O.; Maha, S.; Joseph, K.; Yu, E.; Tai, P. Oncology Nurses’ Attitudes, Knowledge, and Practices in Providing Sexuality Care to Cancer Patients: A Scoping Review. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Evans, D.T. Promoting sexual health and wellbeing: The role of the nurse. Nurs. Stand. 2013, 28, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherven, B.O.; Demedis, J.; Frederick, N.N. Sexual health in adolescents and young adults with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J.; Gilbert, E. Australian Cancer and Sexuality Study Team. Perceived causes and consequences of sexual changes after cancer for women and men: A mixed method study. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krouwel, E.M.; Nicolai, M.P.; van Steijn-van Tol, A.Q.; Putter, H.; Osanto, S.; Pelger, R.C.; Elzevier, H. Addressing changed sexual functioning in cancer patients: A cross-sectional survey among Dutch oncology nurses. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alappattu, M.; Harrington, S.E.; Hill, A.; Roscow, A.; Jeffrey, A. Oncology Section EDGE Task Force on Cancer: A systematic review of patient-reported measures for sexual dysfunction. Rehabil. Oncol. 2017, 35, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bakker, R.M.; Mens, J.W.; de Groot, H.E.; Tuijnman-Raasveld, C.C.; Braat, C.; Hompus, W.C.; Poelman, J.G.; Laman, M.S.; Velema, L.A.; de Kroon, C.D.; et al. A nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention after radiotherapy for gynecological cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barbera, L.; Zwaal, C.; Elterman, D.; McPherson, K.; Wolfman, W.; Katz, A.; Matthew, A.; Interventions to Address Sexual Problems in People with Cancer Guideline Development Group. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2017, 24, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Esmat Hosseini, S.; Ilkhani, M.; Rohani, C.; Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A.; Ghanei Gheshlagh, R.; Moini, A. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2022, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jing, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Jin, F.; Wang, A. Incidence and severity of sexual dysfunction among women with breast cancer: A meta-analysis based on female sexual function index. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1171–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, C.J.; Reiman, A.J.; Brunelle, C.; Best, L.A. Intimacy and sexual functioning after cancer: The intersection with psychological flexibility. PLoS Ment. Health 2024, 1, e0000001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Fact Sheets. World Health Organization, 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). What Constitutes Sexual Health. Progress in Reproductive Health Research; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Volume 67, pp. 2–3.

- Cairo Notari, S.; Favez, N.; Notari, L.; Panes-Ruedin, B.; Antonini, T.; Delaloye, J.F. Women’s experiences of sexual functioning in the early weeks of breast cancer treatment. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouladi, N.; Pourfarzi, F.; Dolattorkpour, N.; Alimohammadi, S.; Mehrara, E. Sexual life after mastectomy in breast cancer survivors: A qualitative study. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, J.R.; Smith, E.; Drizin, J.H.; Lyons, K.S.; Harvey, S.M. Navigating sexual health in cancer survivorship: A dyadic perspective. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 5429–5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, N.; Zhang, Y.; Suo, R.; Dong, W.; Zou, W.; Zhang, M. The role of space in obstructing clinical sexual health education: A qualitative study on breast cancer patients’ perspectives on barriers to expressing sexual concerns. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2021, 30, e13422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.C.; Hu, W.Y.; Chang, Y.M.; Chiu, S.C. Changes in sexual life experienced by women in Taiwan after receiving treatment for breast cancer. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-being 2019, 14, 1654343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reese, J.B.; Sorice, K.A.; Pollard, W.; Zimmaro, L.A.; Beach, M.C.; Handorf, E.; Lepore, S.J. Understanding sexual help-seeking for women with breast cancer: What distinguishes women who seek help from those who do not? J. Sex. Med. 2020, 17, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dyer, K.; das Nair, R. Why don’t healthcare professionals talk about sex? A systematic review of recent qualitative studies conducted in the United kingdom. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 2658–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canzona, M.R.; Ledford, C.J.W.; Fisher, C.L.; Garcia, D.; Raleigh, M.; Kalish, V.B. Clinician barriers to initiating sexual health conversations with breast cancer survivors: The influence of assumptions and situational constraints. Fam. Syst. Health 2018, 36, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, S.R.; Connaghan, J.; Maguire, R.; Kotronoulas, G.; Flannagan, C.; Jain, S.; Brady, N.; McCaughan, E. Healthcare professional perceived barriers and facilitators to discussing sexual wellbeing with patients after diagnosis of chronic illness: A mixed-methods evidence synthesis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 850–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D.; Adams, A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pimsen, A.; Lin, W.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Kuo, Y.L.; Shu, B.C. Healthcare providers’ experiences in providing sexual health care to breast cancer survivors: A mixed-methods systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulou, C.; Sime, C.; Rooney, K.; Kotronoulas, G. Sexual health care provision in cancer nursing care: A systematic review on the state of evidence and deriving international competencies chart for cancer nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 100, 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, A.; Li, Y.; Sun, H.; Jiao, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Incidence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in young breast cancer survivors. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 4428–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tramacere, F.; Lancellotta, V.; Casà, C.; Fionda, B.; Cornacchione, P.; Mazzarella, C.; de Vincenzo, R.P.; Macchia, G.; Ferioli, M.; Rovirosa, A.; et al. Assessment of sexual dysfunction in cervical cancer patients after different treatment modality: A systematic review. Medicina 2022, 58, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tee, B.C.; Ahmad Rasidi, M.S.; Mohd Rushdan, M.N.; Ismail, A.; Sidi, H. The prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in gynecological cancer patients. Med. Health Univ. Kebangs. Malays. 2014, 9, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Oldertrøen Solli, K.; de Boer, M.; Nyheim Solbrække, K.; Thoresen, L. Male partners’ experiences of caregiving for women with cervical cancer—A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, A.; Vistad, I.; Fegran, L. Nurse-patient sexual health communication in gynecological cancer follow-up: A qualitative study from nurses’ perspectives. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 4648–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schover, L.R.; van der Kaaij, M.; van Dorst, E.; Creutzberg, C.; Huyghe, E.; Kiserud, C.E. Sexual dysfunction and infertility as late effects of cancer treatment. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. 2014, 12, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagle, J.G.; Bolte, S. Sexuality and life-threatening illness: Implications for social work and palliative care. Health Soc. Work. 2009, 34, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redelman, M.J. Is there a place for sexuality in the holistic care of patients in the palliative care phase of life? Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 2008, 25, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wazqar, D.Y. Sexual health care in cancer patients: A survey of healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes and barriers. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4239–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedde, H.; van de Wiel, H.B.; Weijmar Schultz, W.C.; Wijsen, C. Sexual dysfunction in young women with breast cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serçekuş Ak, P.; Partlak Günüşen, N.; Göral Türkcü, S.; Özkan, S. Sexuality in Muslim Women with Gynecological Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2020, 43, E47–E53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, S.E.; Mohamed, H.E. Handling sexuality concerns in women with gynecological cancer: Egyptian nurse’s knowledge and attitudes. J. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 146–159. [Google Scholar]

- Åling, M.; Lindgren, A.; Löfall, H.; Okenwa-Emegwa, L. A Scoping Review to Identify Barriers and Enabling Factors for Nurse-Patient Discussions on Sexuality and Sexual Health. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Neenan, C.; Chatzi, A.V. Quality of Nursing Care: Addressing Sexuality as Part of Prostate Cancer Management, an Umbrella Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 4485–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Forbat, L.; White, I.; Marshall-Lucette, S.; Kelly, D. Discussing the sexual consequences of treatment in radiotherapy and urology consultations with couples affected by prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012, 109, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twitchell, D.K.; Wittmann, D.A.; Hotaling, J.M.; Pastuszak, A.W. Psychological Impacts of Male Sexual Dysfunction in Pelvic Cancer Survivorship. Sex. Med. Rev. 2019, 7, 614–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, E.; Tanriseven, M.; Ersoz, N.; Oztas, M.; Ozerhan, I.H.; Kilbas, Z.; Demirbas, S. Urinary and sexual dysfunction rates and risk factors following rectal cancer surgery. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2015, 30, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.; Lacchetti, C.; Andersen, B.L.; Barton, D.L.; Bolte, S.; Damast, S.; Diefenbach, M.A.; DuHamel, K.; Florendo, J.; Ganz, P.A.; et al. Interventions to Address Sexual Problems in People With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsdottir, J.I.; Zoëga, S.; Saevarsdottir, T.; Sverrisdottir, A.; Thorsdottir, T.; Einarsson, G.V.; Gunnarsdottir, S.; Fridriksdottir, N. Changes in attitudes, practices and barriers among oncology health care professionals regarding sexual health care: Outcomes from a 2-year educational intervention at a University Hospital. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 21, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, C.L.; Lengacher, C.A.; Donovan, K.A.; Kip, K.E.; Tofthagen, C.S. Body image in younger breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2016, 39, E39–E58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-02-2024-global-cancer-burden-growing--amidst-mounting-need-for-services (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Sexual and Reproductive Health: Defining Sexual Health. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research/key-areas-of-work/sexual-health/defining-sexual-health (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- What Constitutes Sexual Health? Progress in Reproductive Health Research 2009. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research-(srh)/overview (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Dai, Y.; Cook, O.Y.; Yeganeh, L.; Huang, C.; Ding, J.; Johnson, C.E. Patient-Reported Barriers and Facilitators to Seeking and Accessing Support in Gynecologic and Breast Cancer Survivors with Sexual Problems: A Systematic Review of Qualitative and Quantitative Studies. J. Sex. Med. 2020, 17, 1326–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vizza, R.; Capomolla, E.M.; Tosetto, L.; Corrado, G.; Bruno, V.; Chiofalo, B.; Di Lisa, F.S.; Filomeno, L.; Pizzuti, L.; Krasniqi, E.; et al. Sexual dysfunctions in breast cancer patients: Evidence in context. Sex. Med. Rev. 2023, 11, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maree, J.; Fitch, M.I. Holding conversations with cancer patients about sexuality: Perspectives from Canadian and African healthcare professionals. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2019, 29, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Yang, Y.; Hwang, E.S. The effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions focused on sexuality in cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2015, 38, E32–E42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.P.; Wilson, C.M.; Rowe, K.; Snyder, J.; Dodson, M.; Deshmukh, V.; Newman, M.; Fraser, A.; Smith, K.; Date, A.; et al. Sexual dysfunction among gynecologic cancer survivors in a population-based cohort study. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 31, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Valpey, R.; Kucherer, S.; Nguyen, J. Sexual dysfunction in female cancer survivors: A narrative review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.C.; Chang, S.R.; Chiu, S.C. Sexual Problems of Patients with Breast Cancer After Treatment: A Systematic Review. Cancer Nurs. 2019, 42, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candy, B.; Chi, Y.; Graham-Wisener, L.; Jones, L.; King, M.; Lanceley, A.; Vickerstaff, V.; Tookman, A. Interventions for sexual dysfunction following treatments for cancer in women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2022, CD005540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pup, L.; Nappi, R.E.; Biglia, N. Sexual dysfunction in gynecologic cancer patients. World Cancer Res. J. 2017, 4, e835. [Google Scholar]

- Cihan, E.; Vural, F. Effect of a telephone-based perioperative nurse-led counselling program on unmet needs, quality of life and sexual function in colorectal cancer patients: A non-randomized study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 68, 102504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: www.cancertherapyadvisor.com (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Karacan, Y.; Yildiz, H.; Demircioglu, B.; Ali, R. Evaluation of sexual dysfunction in patients with hematological malignancies. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 8, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Olsson, C.; Sandin-Bojö, A.K.; Bjuresäter, K.; Larsson, M. Changes in sexuality, body image and health related quality of life in patients treated for hematologic malignancies: A longitudinal study. Sex. Disabil. 2016, 34, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quinn, C.; Platania-Phung, C.; Bale, C.; Happell, B.; Hughes, E. Understanding the current sexual health service provision for mental health consumers by nurses in mental health settings: Findings from a survey in Australia and England. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 1522–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M.G. Sexuality and menopause: Unique issues in gynecologic cancer. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 35, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ghabeesh, S.H.; Al-Kalaldah, M.; Rayan, A.; Al-Rifai, A.; Al-Halaiqa, F. Psychological distress and quality of life among Jordanian women diagnosed with breast cancer: The role of trait mindfulness. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.C.; Liu, X.; Loke, A.Y. Addressing sexuality issues of women with gynecological cancer: Chinese nurses’ attitudes and practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reese, J.B.; Beach, M.C.; Smith, K.C.; Bantug, E.T.; Casale, K.E.; Porter, L.S.; Bober, S.L.; Tulsky, J.A.; Daly, M.B.; Lepore, S.J. Effective patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in breast cancer: A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 3199–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al-Ghabeesh, S.H.; Bashayreh, I.H.; Saifan, A.R.; Rayan, A.; Alshraifeen, A.A. Barriers to effective pain management in cancer patients from the perspective of patients and family caregivers: A qualitative study. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2020, 21, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roushar, A. 9th Conference of the Scientific Network of Female Sexual Health and Cancer. Cancersexnetwork.org. 2024. Available online: https://www.cancersexnetwork.org/events/annual-meeting/past-meetings/2024 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Eid, K.; Christensen, S.; Hoff, J.; Yadav, K.; Burtson, P.; Kuriakose, M.; Patton, H.; Nyamathi, A. Sexual health education: Knowledge level of oncology nurses and barriers to discussing concerns with patients. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 24, E50–E56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.C.; Li, Q.; Wang, N.; Ching, S.S.; Loke, A.Y. Chinese nurses’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality care in cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2011, 34, E14–E20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oskay, Ü.; Can, G.; Başgöl, S. Discussing sexuality with cancer patients: Oncology nurses attitudes and views. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 7321–7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.; Higgins, A.; Sharek, D. Barriers and facilitators for oncology nurses discussing sexual issues with men diagnosed with testicular cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 17, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.blueberrytherapy.ca/post/breaking-the-silence-addressing-the-stigma-surrounding-women-s-sexual-health-in-healthcare-settings (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Shahin, M.A.; Gaafar, H.A.A.; Alqersh, D.L.A. Effect of nursing counseling guided by BETTER model on sexuality, marital satisfaction and psychological status among breast cancer women. Egypt. J. Health Care 2021, 12, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrad, H.; Chouinard, A.; Pichette, R.; Piché, L.; Bilodeau, K. Feasibility and impact of an online simulation focusing on nursing communication about sexual health in gynecologic oncology. J. Cancer Educ. 2024, 39, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa Rodrigues Guedes, T.; Barbosa Otoni Gonçalves Guedes, M.; de Castro Santana, R.; Costa da Silva, J.F.; Almeida Gomes Dantas, A.; Ochandorena-Acha, M.; Terradas-Monllor, M.; Jerez-Roig, J.; Bezerra de Souza, D.L. Sexual dysfunction in women with cancer: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Williams, N.F.; Hauck, Y.L.; Bosco, A.M. Nurses’ perceptions of providing psychosexual care for women experiencing gynecological cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 30, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, K.; Davis, M.E. Cancer in sexual and gender minorities: Role of oncology RNs in health equity. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 28, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, K.M.; Chan, C.W.H.; Choi, K.C.; White, I.D.; Siu, K.Y.; Sin, W.H. A practice model of sexuality nursing care: A concept mapping approach. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 1663–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, O.; McIntyre, M.; Recoche, K. Exploration of the role of specialist nurses in the care of women with gynecological canc er: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 24, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vocht, H.; Hordern, A.; Notter, J.; van de Wiel, H. Stepped Skills: A team approach toward communication about sexuality and intimacy in cancer and palliative care. Australas. Med. J. 2011, 4, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suvaal, I.; Hummel, S.B.; Mens, J.M.; Tuijnman-Raasveld, C.C.; Tsonaka, R.; Velema, L.A.; Westerveld, H.; Cnossen, J.S.; Snyers, A.; Jürgenliemk-Schulz, I.M.; et al. Efficacy of a nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention for women with gynecological cancers receiving radiotherapy: Results of a randomized trial. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Katz, A. Symptom Management Guidelines for Oncology Nursing; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. A workshop for educating nurses to address sexual health in patients with breast cancer. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 248–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research-%28srh%29/overview (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Ahn, S.H.; Kim, J.H. Healthcare professionals’ attitudes and practice of sexual health care: Preliminary study for developing training program. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 559851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frederick, N.N.; Campbell, K.; Kenney, L.B.; Moss, K.; Speckhart, A.; Bober, S.L. Barriers and facilitators to sexual and reproductive health communication between pediatric oncology clinicians and adolescent and young adult patients: The clinician perspective. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e27087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahouri, A.; Sahebihagh, M.H.; Gilani, N. Factors associated with sexual dysfunction in patients with colorectal cancer in Iran: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Whitlock, E.P.; Orleans, C.T.; Pender, N.; Allan, J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: An evi dence-based approach. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, C.B.; Jensen, P.T.; Groenvold, M.; Johnsen, A.T. Prevalence and possible predictors of sexual dysfunction and self-reported needs related to the sexual life of advanced cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, R.A.; Bonfim, C.V.D.; Feitosa, K.M.A.; Furtado, B.M.A.S.M.; Ferreira, D.K.D.S.; Santos, S.L.D. Sexual dysfunction after cervical cancer treatment. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP. 2020, 54, e03636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).