Barriers and Enablers to Engaging with Long-Term Follow-Up Care Among Canadian Survivors of Pediatric Cancer: A COM-B Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient and Public Involvement

2.2. Participants

2.3. Recruitement

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Barriers and Enablers to Attending LTFU Care

2.5.2. Participant Characteristics

2.6. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant and Clinical Characteristics

3.1.1. Survivors

3.1.2. Healthcare Providers

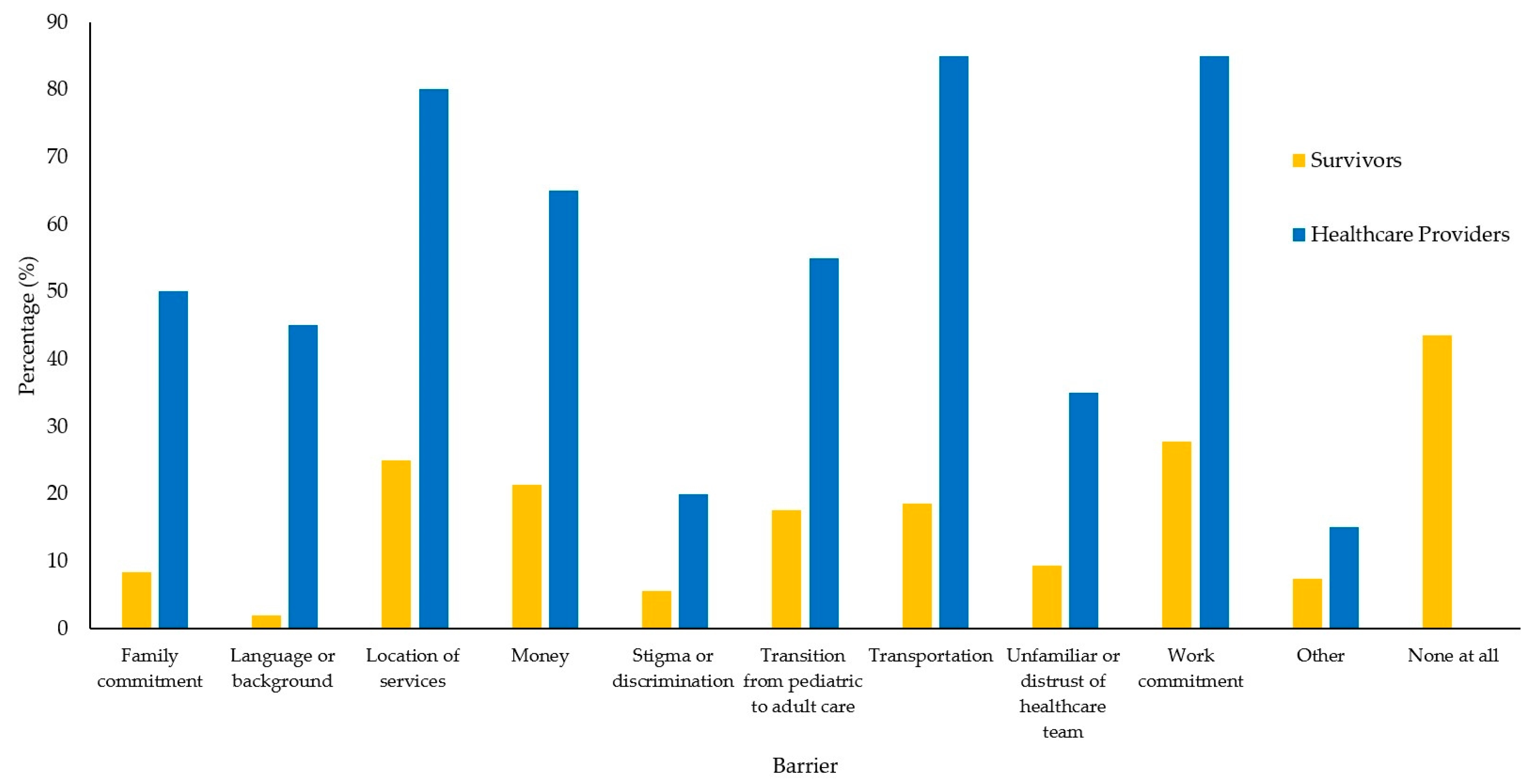

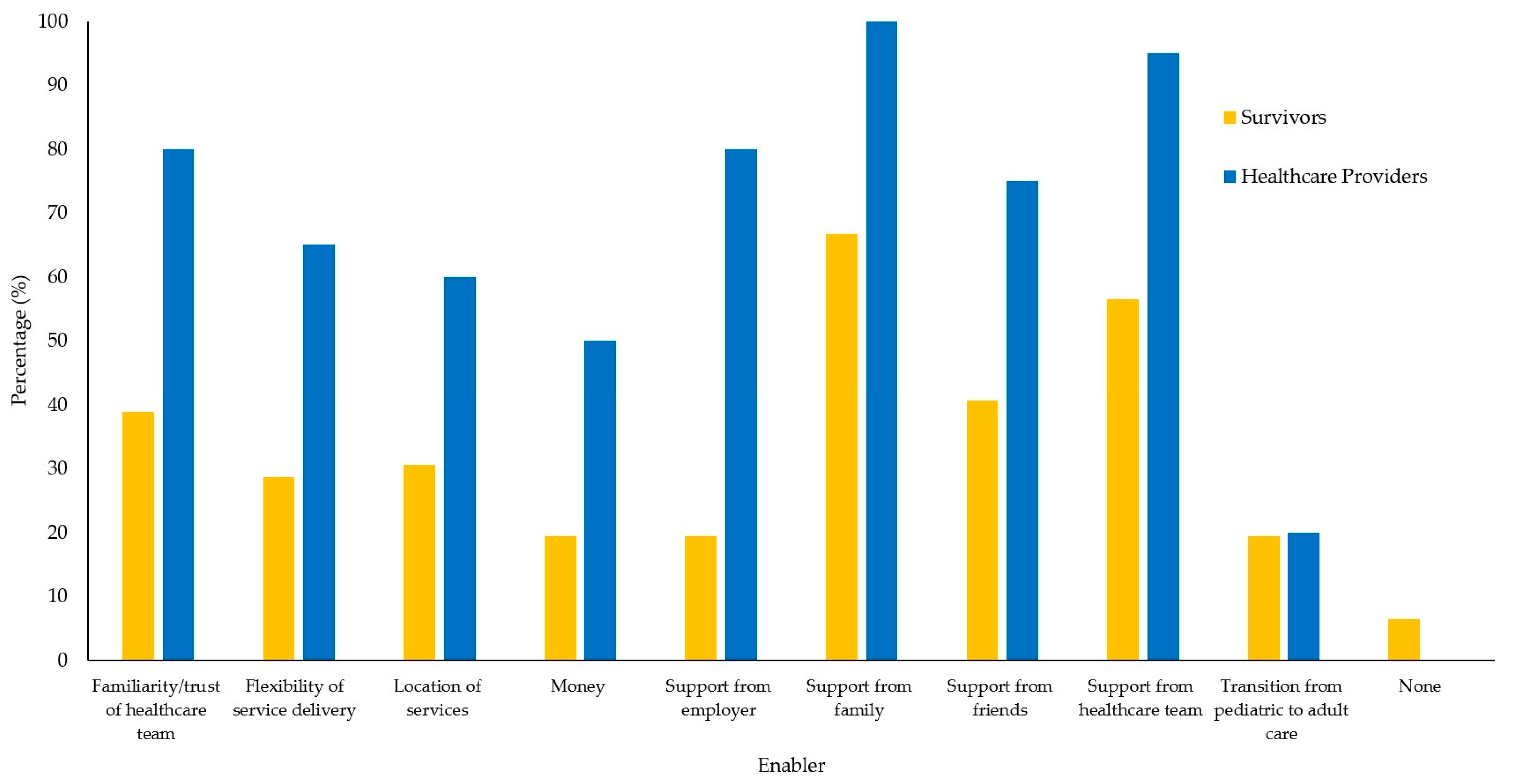

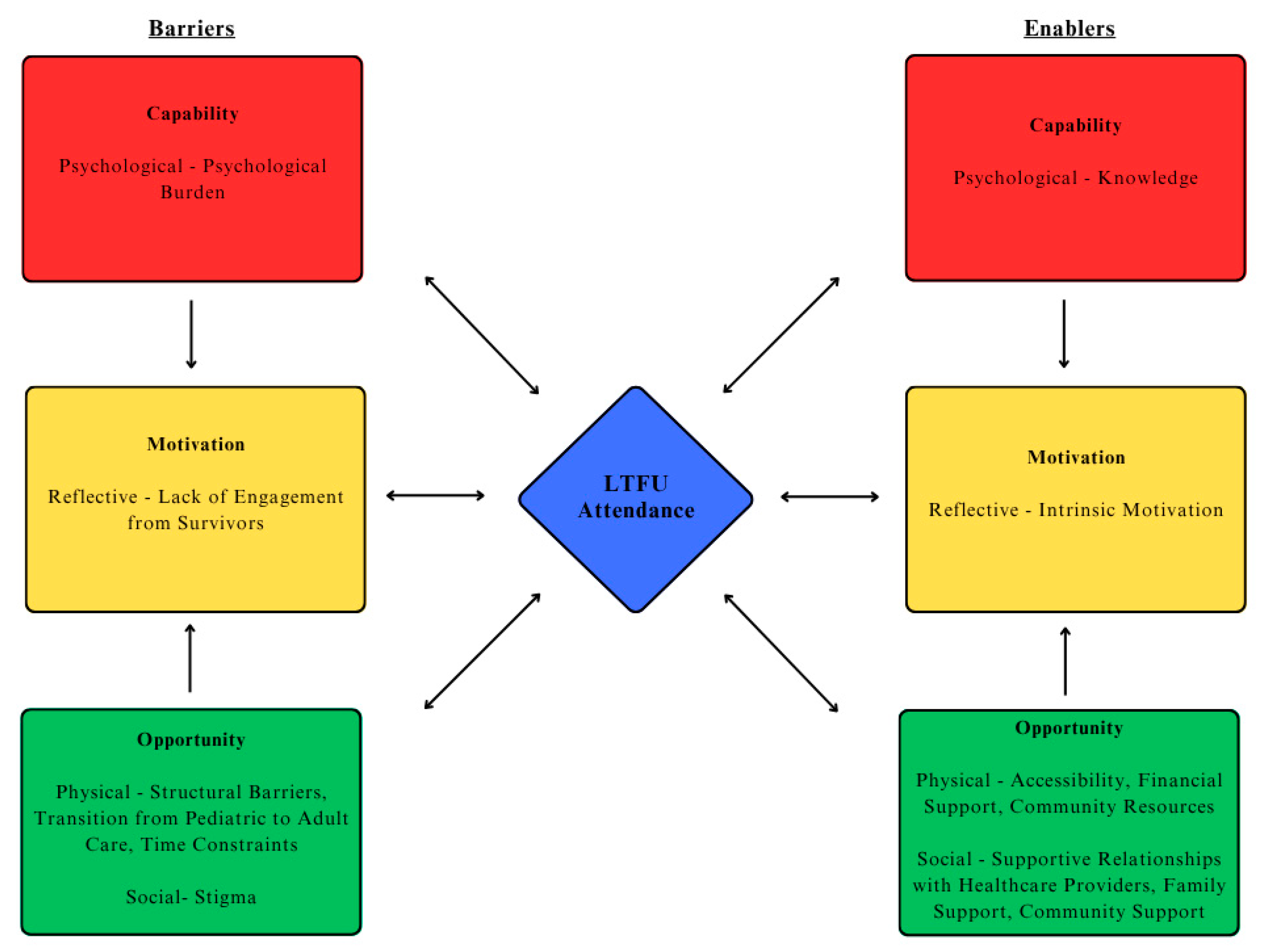

3.2. Perceived Barriers and Enablers to Engaging with Follow-Up Care

3.2.1. Capability: Psychological

“I went to aftercare, I would say sporadically. And then just found it very anxiety provoking and miserable experience all around. And did not find any benefit in it.”—Survivor Participant ID 128

“There came a point where I just was fed up with living in the cancer system, and, for better or worse, was willing to talk the risk of I don’t want to do this- I want to have a life.”—Survivor Participant ID 128

“Going back to the enabling question, I think knowledge. The medical professionals being very open about my condition, what everything meant. Giving me that education to be able to understand what’s going on and not being scared to ask questions it allowed me to advocate for myself because I knew what I was talking about.”—Survivor Participant ID 144

3.2.2. Opportunity: Physical

“One of the biggest barriers is just geographic I think, and that ties into financial, because for some families that trip down to [city] in a location that’s very expensive to get down to and to stay at”—HCP Participant ID 2

“Physically moving to provinces is a huge barrier now, that I’ve learned, and encountering disparity in the way clinics in provinces may approach aftercare is a huge piece of that.”—Survivor Participant ID 77

“I find that when you’re in the pediatric world, there is a lot of people that do a lot of hand-holding and help you to navigate the world that you’re working with within ped. But then when you turn to be an adult, they kind of throw you to the wolves and expect you to figure it out.”—Survivor Participant ID

“For me, the barriers in just getting, it was for follow-up appointments, was just the time.—Survivor ID 59

“Because we’re a provincial program, one of the interesting things about doing everything virtually is it sort of flattens the access more. So the ability to connect with people is kind of equalized, whether you live in [location] and [location] or you live in [location] it doesn’t matter, I can see you by phone or by Zoom either place.”—HCP ID 80

“I think the biggest enabler for actually having these appointments for me is that they’re scheduled for me and then they’re put in my like hospital calendar app.—Survivor ID 44

“We would always have to book a hotel room and things like that, and the social worker was great in helping us. So it was kind of they had support, like if they had a gas card they can help with that.”—Survivor ID 85

“Like I said, huge is mental health supports. I mean, we do have the [organization], we’re very lucky to have the [organization], that is an external organisation that provides some counselling.”—HCP ID 2

3.2.3. Opportunity: Social

“Seeing those familiar faces, was definitely one of the reasons that when I did go, was one of the positives.”—Survivor ID 128

“I have a great relationship with my care team, it makes the world of difference, because you do feel safe and you don’t feel silly in going for little things.”—Survivor ID 85

“Ultimately as a young person, your family is getting you to those appointments and they’re also helping you see the value of them, too…at least from my experience, part of why I also kept going to aftercare was because it was important to my mom and my family.”—Survivor ID 77

“I also feel like sometimes when you go and, yes, you are surrounded by children who are going through it, it takes you back but you’re also “hey, these people, these kids, they look at me and they’re ‘hey, I can beat this, right?” So having you go there it’s almost like you’re giving them a sense of hope.”—Survivor ID 87

3.2.4. Motivation: Reflective

“I would say another barrier because it’s that transition from care as a child, or a young person, into the adult world we really take the perspective of, you’re the adult now so it’s your care, you need to be engaged.”—HCP Participant ID 80

“There’s no incentive for me to go, it’s just other than keeping myself healthy.”—Survivor Participant ID 6

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee; Canadian Cancer Society; Statistics Canada; Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2023; Canadian Cancer Society: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023; Available online: http://cancer.ca/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2023-EN (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Freyer, D.R. Transition of Care for Young Adult Survivors of Childhood and Adolescent Cancer: Rationale and Approaches. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4810–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, A.F.; Kazanjian, A.; Pritchard, S.; Olson, R.; Hasan, H.; Newton, K.; Goddard, K. Healthcare system barriers to long-term follow-up for adult survivors of childhood cancer in British Columbia, Canada: A qualitative study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 12, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, M.M.; Mertens, A.C.; Yasui, Y.; Hobbie, W.; Chen, H.; Gurney, J.G.; Yeazel, M.; Recklitis, C.J.; Marina, N.; Robison, L.R.; et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 2003, 290, 1583–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, A.; Borthwick, S.; Duffin, K.; Marciniak-Stepak, P.; Wallace, W. Survivors of childhood cancer lost to follow-up can be re-engaged into active long-term follow-up by a postal health questionnaire intervention. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, A.; Kuperberg, A. Psychosocial Support in Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer. Cancer J. 2018, 24, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoone, J.K.; Sansom-Daly, U.M.; Paglia, A.; Chia, J.; Larsen, H.B.; Fern, L.A.; Cohn, R.J. A Scoping Review Exploring Access to Survivorship Care for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors: How Can We Optimize Care Pathways? Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2023, 14, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, M.; Brähler, E.; Faber, J.; Wild, P.S.; Merzenich, H.; Beutel, M.E. A Mixed-Methods Investigation of Medical Fol-low-Up in Long-Term Childhood Cancer Survivors: What Are the Reasons for Non-Attendance? Front Psychol. 2022, 13, 846671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knighting, K.; Kirton, J.A.; Thorp, N.; Hayden, J.; Appleton, L.; Bray, L. A study of childhood cancer survivors’ engagement with long-term follow-up care: ‘To attend or not to attend, that is the question’. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 45, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuldiner, J.; Shah, N.; Corrado, A.M.; Hodgson, D.; Nathan, P.C.; Ivers, N. Determinants of surveillance for late effects in childhood cancer survivors: A qualitative study using the Theoretical Domains Framework. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 16, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillen, J.; Bradley, H.; Calamaro, C. Identifying Barriers Among Childhood Cancer Survivors Transitioning to Adult Health Care. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 34, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebrack, B.J.; Eshelman, D.A.; Hudson, M.M.; Mertens, A.C.; Cotter, K.L.; Foster, B.M.; Loftis, L.; Sozio, M.; Oeffinger, K.C. Health Care for Childhood Cancer Survivors Insights and Perspectives from a Delphi Panel of Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. Cancer 2004, 100, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otth, M.; Denzler, S.; Koenig, C.; Koehler, H.; Scheinemann, K. Transition from pediatric to adult follow-up care in childhood cancer survivors—A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 15, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, H.; Gramatges, M.; Dreyer, Z.A.; Okcu, M.F.; Shakeel, O. Barriers to long-term follow-up in pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2024, 71, e30855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Cheung, Y.T.; Hudson, M.M. Care Models and Barriers to Long-Term Follow-Up Care Among Childhood Cancer Survivors and Health Care Providers in Asia: A Literature Review. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2024, 10, e2300331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossert, S.; Borenzweig, W.; Benedict, C.; Cerise, J.E.; Siembida, E.J.; Fish, J.D. Barriers to Receiving Follow-up Care Among Childhood Cancer Survivors. J. Pediatr. Hematol. 2023, 45, e827–e832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, M.; Goswami, S. Barriers to long-term follow-up in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer: Perspectives from a low–middle income setting. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, e29248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.J.; Stratton, E.; Esiashvili, N.; Mertens, A. Young Adult Cancer Survivors’ Experience with Cancer Treatment and Follow-Up Care and Perceptions of Barriers to Engaging in Recommended Care. J. Cancer Educ. 2015, 31, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg-Yunger, Z.R.S.; Klassen, A.F.; Amin, L.; Granek, L.; D’Agostino, N.M.; Boydell, K.M.; Greenberg, M.; Barr, R.D.; Nathan, P.C. Barriers and Facilitators of Transition from Pediatric to Adult Long-Term Follow-Up Care in Childhood Cancer Survivors. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2013, 2, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, C.; Wakefield, C.; McLoone, J.K.; Fardell, J.; Jones, J.M.; Turpin, K.H.; Emery, J.; Michel, G.; Downie, P.E.; Skeen, J.; et al. Childhood cancer survivorship: Barriers and preferences. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2019, 12, e687–e695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, A.C.; Lyles, C.R.; Fluchel, M.; Wright, J.; Leisenring, W. Limitations in health care access and utilization among long-term survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer. Cancer 2012, 118, 5964–5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeffinger, K.C.; Wallace, W.H.B. Barriers to follow-up care of survivors in the United States and the United King-dom. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2006, 46, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshelman-Kent, D.; Kinahan, K.E.; Hobbie, W.; Landier, W.; Teal, S.; Friedman, D.; Nagarajan, R.; Freyer, D.R. Cancer survivorship practices, services, and delivery: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) nursing discipline, adolescent/young adult, and late effects committees. J. Cancer Surviv. 2011, 5, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziz, N.M.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Brooks, S.; Turoff, A.J. Comprehensive long-term follow-up programs for pediatric cancer survivors. Cancer 2006, 107, 841–848. [Google Scholar]

- Sadak, K.T.; Szalda, D.; Lindgren, B.R.; Kinahan, K.E.; Eshelman-Kent, D.; Schwartz, L.A.; Henderson, T.; Freyer, D.R. Transitional care practices, services, and delivery in childhood cancer survivor programs: A survey study of U.S. survivorship providers. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, C.; Stratton, E.; Esiashvili, N.; Mertens, A.; Vanderpool, R.C. Providers’ Perspectives of Survivorship Care for Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. J. Cancer Educ. 2015, 31, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, A.C.; Cotter, K.L.; Foster, B.M.; Zebrack, B.J.; Hudson, M.M.; Eshelman, D.; Loftis, L.; Sozio, M.; Oeffinger, K.C. Improving health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer: Recommendations from a delphi panel of health policy experts. Health Policy 2004, 69, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.T.; Zhang, H.; Cai, J.; Au-Doung, L.W.P.; Yang, L.S.; Yan, C.; Zhou, F.; Chen, X.; Guan, X.; Pui, C.-H.; et al. Identifying Priorities for Harmonizing Guidelines for the Long-Term Surveillance of Childhood Cancer Survivors in the Chinese Children Cancer Group (CCCG). JCO Glob. Oncol. 2021, 7, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effinger, K.E.; Haardörfer, R.; Marchak, J.G.; Escoffery, C.; Landier, W.; Kommajosula, A.; Hendershot, E.; Sadak, K.T.; Eshelman-Kent, D.; Kinahan, K.; et al. Current pediatric cancer survivorship practices: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Cancer Surviv. 2022, 17, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.; Schulte, F.; Guilcher, G.M.T.; Truong, T.H.; Reynolds, K.; Spavor, M.; Logie, N.; Lee, J.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.M. Alberta Childhood Cancer Survivorship Research Program. Cancers 2023, 15, 3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childhood Cancer Survivor Canada Access 2024. Available online: https://childhoodcancersurvivor.org/access/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Ivers, N.; Brown, A.D.; Detsky, A.S. Lessons from the Canadian experience with single-payer health insurance just comfortable enough with the status quo. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, P.C.; Agha, M.; Pole, J.D.; Hodgson, D.; Guttmann, A.; Sutradhar, R.; Greenberg, M.L. Predictors of attendance at specialized survivor clinics in a population-based cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 10, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, T.K.; Tabish, T.; Young, S.K.; Healey, G. Patient transportation in Canada’s northern territories: Patterns, costs and providers’ perspectives. Rural. Remote Health 2019, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keaver, L.; Douglas, P.; O’callaghan, N. Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to a Healthy Diet among Cancer Survivors: A Qualitative Exploration Using the TDF and COM-B. Dietetics 2023, 2, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.-C.; Judah, G.; Cunningham, D.; Olander, E.K. Individualised physical activity and physiotherapy behaviour change intervention tool for breast cancer survivors using self-efficacy and COM-B: Feasibility study. Eur. J. Physiother. 2020, 24, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ee, C.; MacMillan, F.; Boyages, J.; McBride, K. Barriers and enablers of weight management after breast cancer: A thematic analysis of free text survey responses using the COM-B model. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.H.J.; Henry, B.; Drummond, R.; Forbes, C.; Mendonça, K.; Wright, H.; Rahamatullah, I.; Tutelman, P.R.; Zwicker, H.; Stokoe, M.; et al. Co-Designing Priority Components of an mHealth Intervention to Enhance Follow-Up Care in Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer and Health Care Providers: Qualitative Descriptive Study. JMIR Cancer 2025, 11, e57834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Fernández, R.; Aggarwal, N.K.; Hinton, L.; Hinton, D.E.; Kirmayer, L.J. DSM-5® Handbook on the Cultural Formulation Interview. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 173, 195–196. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.L.; Blefari, C.; Marotti, S. Application of the COM-B model to explore barriers and facilitators to participation in research by hospital pharmacists and pharmacy technicians: A cross-sectional mixed-methods survey. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 20, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhani, A.; Finlay, K.A. Using the COM-B model to characterize the barriers and facilitators of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake in men who have sex with men. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 1330–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, B.; Narasimhan, P.; Vaidya, A.; Subedi, M.; Jayasuriya, R. Barriers and facilitators for treatment and control of high blood pressure among hypertensive patients in Kathmandu, Nepal: A qualitative study informed by COM-B model of behavior change. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulou, C. Non-adherence to medication and doctor–patient relationship: Evidence from a European sur-vey. Patient Educ Couns. 2011, 83, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulman, D.M.; Haverfield, M.C.; Shaw, J.G.; Brown-Johnson, C.G.; Schwartz, R.; Tierney, A.A.; Zionts, D.L.; Safaeinili, N.; Fischer, M.; Israni, S.T.; et al. Practices to Foster Physician Presence and Connection With Patients in the Clinical Encounter. JAMA 2020, 323, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, A.J.; Faulkner, G.; Jones, J.M.; Sabiston, C.M. A qualitative analysis of oncology clinicians’ perceptions and barriers for physical activity counseling in breast cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 3117–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasti, S.P.; Simkhada, P.; van Teijlingen, E.; Sathian, B.; Banerjee, I. The Growing Importance of Mixed-Methods Re-search in Health. Nepal J. Epidemiol. 2022, 12, 1175–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawadi, S.; Shrestha, S.; Giri, R.A. Mixed-Methods Research: A Discussion on its Types, Challenges, and Criticisms. J. Pr. Stud. Educ. 2021, 2, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyd, D.H.; Janitz, A.E.; Baker, A.A.; Beasley, W.H.; Etzold, N.C.; Kendrick, D.C.; Oeffinger, K.C. Rural, Large Town, and Urban Differences in Optimal Subspecialty Follow-up and Survivorship Care Plan Documentation among Childhood Cancer Survivors. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2023, 32, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, K.; Belanger, B.; Parshad, S.; Xie, L.; Grywacheski, V.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M. Late Mortality Among Survivors of Childhood Cancer in Canada: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2025, 72, e31700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, E.M.; Moke, D.J.; Milam, J.; Ochoa-Dominguez, C.Y.; Stal, J.; Mitchell, H.; Aminzadeh, N.; Bolshakova, M.; Vega, R.B.M.; Dinalo, J.; et al. Disparities in pediatric cancer survivorship care: A systematic review. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 18281–18305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshchenko, E.; Langer, T.; Calaminus, G.; Gebauer, J.; Swart, E.; Baust, K. Organizing long-term follow-up care for pediatric cancer survivors: A socio-ecological approach. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1524310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survivors of Pediatric Cancer—Demographic and Clinical Characteristics | Survey Participants n = 108 | Focus Group Participants n = 22 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | |

| Current age (in years) | 105 | 28.30 (5.27) | 21 | 29.19 (4.78) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 32 (29.6) | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Female | 76 (70.4) | 21 (95.5) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 31 (28.7) | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Female | 74 (68.5) | 21 (95.5) | ||

| Gender Fluid, Non-binary or Two-Spirit | 3 (2.8) | |||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Aboriginal/First Nations/Inuit/Métis | 3 (2.8) | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Black/African/Caribbean | 3 (2.8) | 1 (4.5) | ||

| East Asian | 14 (13.0) | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Latin American | 1 (0.9) | |||

| Middle Eastern | 3 (2.8) | |||

| South Asian | 5 (4.6) | |||

| White/European | 85 (78.7) | 19 (86.4) | ||

| Other | 2 (1.9) | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Province of Residence | ||||

| Alberta | 38 (35.2) | 10 (45.5) | ||

| British Columbia | 37 (34.3) | |||

| New Brunswick | 2 (1.9) | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Nova Scotia | 5 (4.6) | 4 (18.2) | ||

| Ontario | 19 (17.6) | 5 (22.7) | ||

| Quebec | 2 (1.9) | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Saskatchewan | 1 (0.9) | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Yukon | 1 (0.9) | |||

| No Response | 3 (2.8) | |||

| Geographic Region | ||||

| Rural | 20 (18.5) | 4 (18.2) | ||

| Urban | 83 (76.9) | 18 (81.8) | ||

| Remote | 2 (1.9) | |||

| No Response | 3 (2.8) | |||

| Age at Diagnosis (in years) | 108 | 9.71 (5.34) | 10.59 (5.45) | |

| Years post-treatment | 108 | 16.60 (7.43) | 17.45 (6.81) | |

| Cancer Diagnosis | ||||

| Leukemia (e.g., ALL, AML) | 36 (33.3) | 11 (50) | ||

| Lymphoma (e.g., Hodgkin’s, non-Hodgkin’s) | 22 (20.4) | 6 (27.3) | ||

| Solid Tumour (e.g., Wilms tumour, | 23 (21.3) | 3 (13.6) | ||

| osteosarcoma) | ||||

| Brain Tumour (e.g., Medulloblastoma) | 12 (11.1) | |||

| Other | 15 (13.9) | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Recruitment | ||||

| Hospital/Clinic | 50 (46.3) | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Twitter/Facebook/Instagram/Internet | 14 (13.0) | 6 (5.6) | ||

| Colleague | 4 (3.7) | |||

| Family/Friend | 7 (6.5) | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Community Organization | 9 (8.3) | 1 (4.5) | ||

| No Response | 24 (22.2) | 11 (50.0) | ||

| Healthcare Providers—Demographic and Professional Characteristics | Survey Participants (n = 20) | Interview Participants (n = 7) | ||

| Current Age (in years) | 20 | 48.3 (9.41) | 7 | 50.14 (7.73) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 4 (20.0) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Female | 16 (80.0) | 6 (85.7) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 4 (20.0) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Female | 16 (80.0) | 6 (85.7) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White/European | 20 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | ||

| Profession | ||||

| Registered Nurse | 6 (30.0) | 3 (42.9) | ||

| Allied Health Professional | 6 (30.0) | 4 (57.1) | ||

| Nurse Practitioner | 3 (15.0) | |||

| Physician-Oncologist | 5 (25.0) | |||

| Years Working with Survivors of Pediatric Cancer | ||||

| 1–4 years | 6 (30.0) | 2 (28.6) | ||

| 5–9 years | 8 (40.0) | 3 (42.9) | ||

| 10–14 years | 1 (5.0) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| 15 or more years | 5 (25.0) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Province of Residence | ||||

| Alberta | 6 (30.0) | 2 (28.6) | ||

| British Columbia | 5 (25.0) | 3 (42.9) | ||

| Manitoba | 2 (10.0) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Nova Scotia | 2 (10.0) | |||

| Ontario | 4 (20.0) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Prefer Not to Answer | 1 (5.0) | |||

| Geographic Region | ||||

| Urban | 18 (90.0) | 7 (100.0) | ||

| Rural | 2 (10.0) | |||

| COM-B Model | Barriers | Enablers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative (Survey) | Qualitative (Focus Group/Interview) | Quantitative (Survey) | Qualitative (Discussion Group/Interview) | ||||

| Survivors | HCPs | Survivors | HCPs | ||||

| Capability—Individuals’ physical and psychological capacity to engage in an activity | |||||||

| Physical (Individuals’ physical capacity (skills, ability) to engage in an activity) | HCP capacity (HCP): Limited capacity of HCP to provide high-quality LTFU care. | ||||||

| Psychological (Individuals’ capability (memory, knowledge, confidence) to engage in the thought processes of an activity | Language or background | Psychological burden (Survivors): Emotional impact of attending LTFU care. | Knowledge (Survivors): Importance of survivors educating themselves on LTFU to advocate for their LTFU care. | ||||

| n = 2 (1.9%) | n = 9 (45%) | ||||||

| Opportunity—External factors that enable or prevent a behaviour | |||||||

| Physical (Environmental factors that influence a behaviour) | Family commitment | Structural barriers (Survivors and HCP): Distance, cost, and location of LTFU care. Time (Survivors): Finding time in their schedules to attend LTFU care. Transition to adult care (Survivors and HCP): Lack of support in the adult system, negative culture, lack of specific resources. | Flexibility of service delivery | Accessibility (Survivors and HCP): Format of care, reminders. Financial supports (Survivors): Financial supports (e.g., gas cards). Community resources (HCPs): Community organizations providing extra supports (e.g., counselling, recreational activities). Increase in system funding (HCPs): Provide more mental and physical support. | |||

| n = 9 (8.3%) | n = 10 (50%) | n = 31 (28.7%) | n = 13 (65%) | ||||

| Location of services | Location of services | ||||||

| n = 27 (25%) | n = 16 (80%) | n = 33 (30.6%) | n = 12 (60%) | ||||

| Money | Money | ||||||

| n = 23 (21.3%) | n = 13 (65%) | n = 21 (19.4%) | n = 10 (50%) | ||||

| Transition from pediatric to adult care | Transition from pediatric to adult care | ||||||

| n = 19 (17.6%) | n = 11 (55%) | n = 21 (19.4%) | n = 4 (20%) | ||||

| Transportation | |||||||

| n = 20 (18.5%) | n = 17 (85%) | ||||||

| Work commitment | |||||||

| n = 30 (27.8%) | n = 17 (85%) | ||||||

| Social (Cultural norms, interpersonal influences that influence a behaviour) | Stigma or discrimination | Stigma (Survivors): Issue accessing tests | Familiarity/trust of healthcare team | Supportive relationships with healthcare providers (Survivors): Building trusting relationships with providers. Family support (Survivors): Taught the importance of attending LTFU care by family, assistance with travelling to appointments. Community support (Survivors): Creating a community with other survivors. | |||

| n = 6 (5.6%) | n = 4 (20%) | n = 42 (38.9%) | n = 16 (80%) | ||||

| Support from employer | |||||||

| n = 21 (19.4%) | n = 16 (80%) | ||||||

| Support from family | |||||||

| n = 72 (66.7%) | n = 20 (100%) | ||||||

| Support from friends | |||||||

| n = 44 (40.7%) | n = 15 (75%) | ||||||

| Support from healthcare team | |||||||

| n = 61 (56.5%) | n = 19 (95%) | ||||||

| Motivation—Brain processes that energize and direct behaviour | |||||||

| Reflective (Involves evaluations and plans about a behaviour) | Lack of engagement from survivors (HCP): Perceived lack of interest from survivors in their LTFU care. | Intrinsic motivation (Survivors): Internal belief that LTFU care and their health is important. | |||||

| Autonomic (Emotions and impulses that arise from associative learning and/or innate disposition) | Unfamiliar of distrust of healthcare team | ||||||

| n = 10 (9.3%) | n = 7 (35%) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wright, H.; Hou, S.H.J.; Henry, B.; Drummond, R.; Mendonça, K.; Forbes, C.; Rahamatullah, I.; Duong, J.; Erker, C.; Taccone, M.S.; et al. Barriers and Enablers to Engaging with Long-Term Follow-Up Care Among Canadian Survivors of Pediatric Cancer: A COM-B Analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080427

Wright H, Hou SHJ, Henry B, Drummond R, Mendonça K, Forbes C, Rahamatullah I, Duong J, Erker C, Taccone MS, et al. Barriers and Enablers to Engaging with Long-Term Follow-Up Care Among Canadian Survivors of Pediatric Cancer: A COM-B Analysis. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(8):427. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080427

Chicago/Turabian StyleWright, Holly, Sharon H. J. Hou, Brianna Henry, Rachelle Drummond, Kyle Mendonça, Caitlin Forbes, Iqra Rahamatullah, Jenny Duong, Craig Erker, Michael S. Taccone, and et al. 2025. "Barriers and Enablers to Engaging with Long-Term Follow-Up Care Among Canadian Survivors of Pediatric Cancer: A COM-B Analysis" Current Oncology 32, no. 8: 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080427

APA StyleWright, H., Hou, S. H. J., Henry, B., Drummond, R., Mendonça, K., Forbes, C., Rahamatullah, I., Duong, J., Erker, C., Taccone, M. S., Sutherland, R. L., Nathan, P. C., Spavor, M., Goddard, K., Reynolds, K., Paulse, S., Flanders, A., & Schulte, F. S. M. (2025). Barriers and Enablers to Engaging with Long-Term Follow-Up Care Among Canadian Survivors of Pediatric Cancer: A COM-B Analysis. Current Oncology, 32(8), 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080427