Beyond Barriers: Achieving True Equity in Cancer Care

Abstract

1. Introduction to Disparities in Cancer Care

1.1. Defining Socioeconomic Disparities

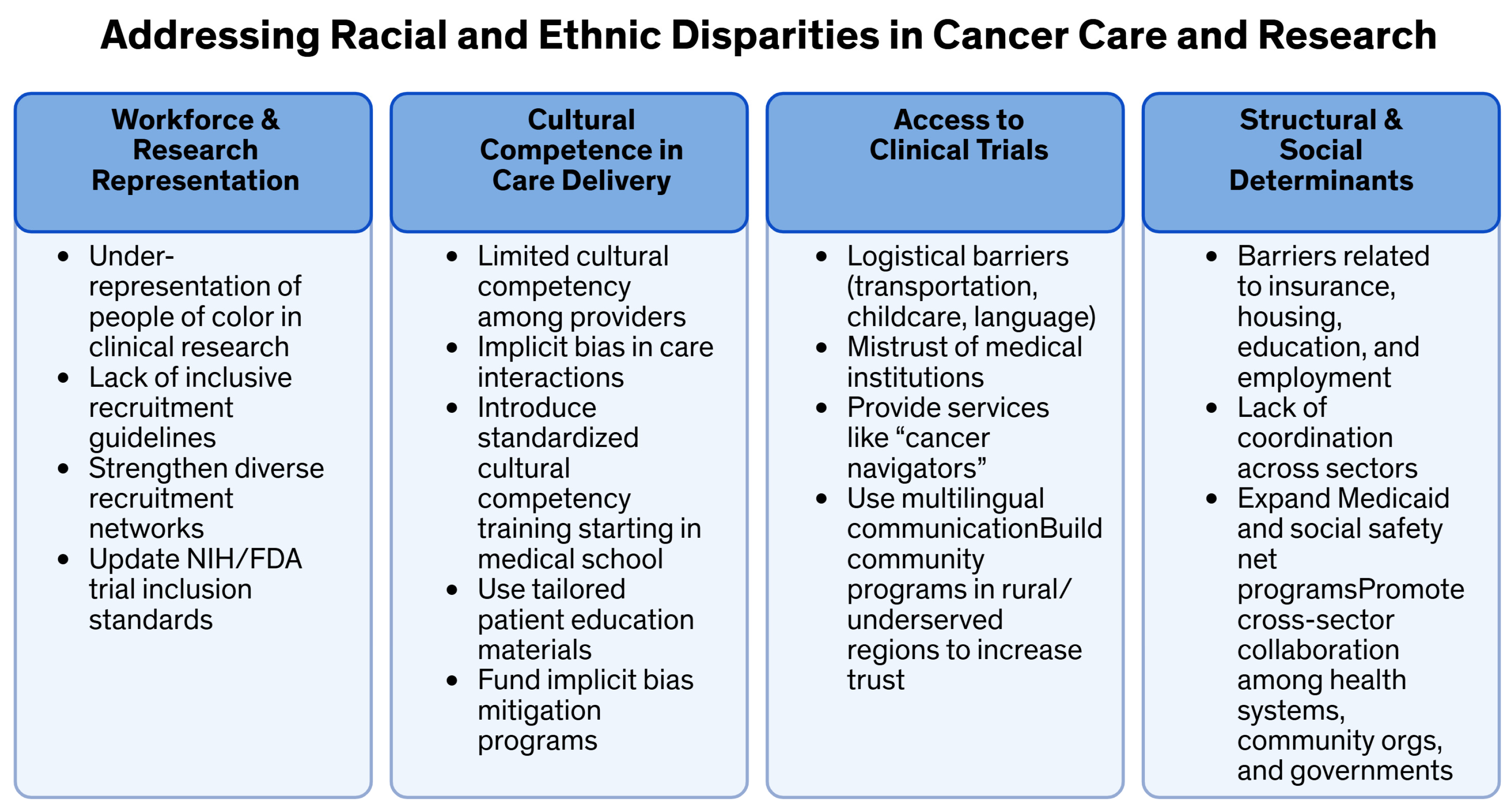

1.2. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Cancer Care

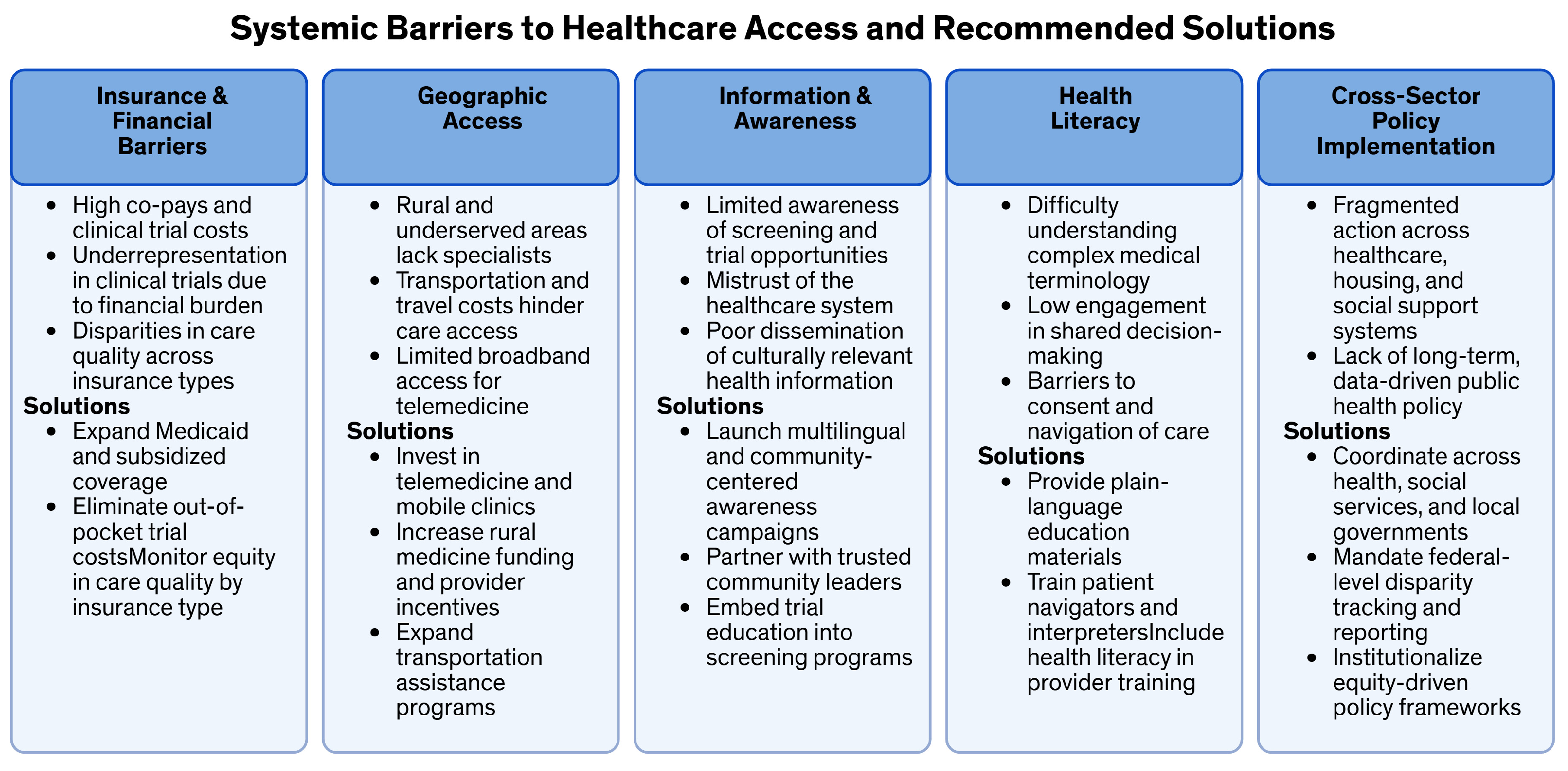

1.3. Insurance-Based Disparities

2. Systemic Barriers to Access

2.1. Geographic Disparities

2.2. Healthcare Provider Bias

2.3. Lack of Health Literacy

3. Impact of Disparities on Cancer Outcomes

3.1. Delayed Diagnosis and Advanced Stage at Presentation

3.2. Differences in Treatment Options and Quality of Care

3.3. Survival Rates and Mortality Disparities

4. Barriers to Participation in Clinical Trials

4.1. Underrepresentation of Minorities in Clinical Trials

4.2. Financial Barriers

4.3. Access to Information and Awareness

5. Strategies to Address Disparities

5.1. Community-Based Interventions

5.2. Cultural Competency Training for Healthcare Providers

6. Policy Recommendations

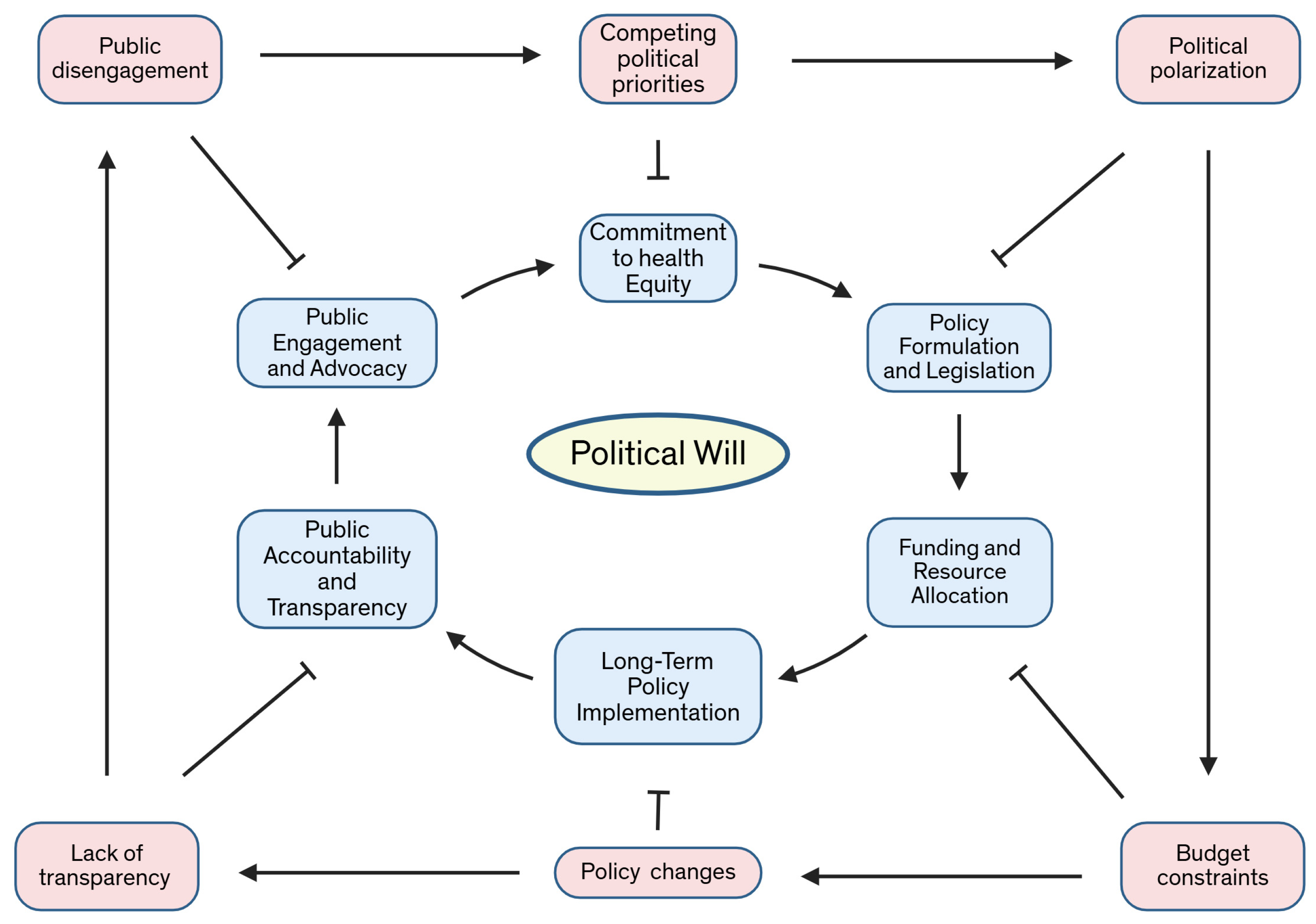

7. Future Directions and Political Will

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Penchansky, R.; Thomas, J.W. The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med. Care 1981, 19, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.A.; Kumanyika, S.; Fielding, J.; Laveist, T.; Borrell, L.N.; Manderscheid, R.; Troutman, A. Health disparities and health equity: The issue is justice. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101 (Suppl. S1), 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129 (Suppl. S2), 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, E.; Jemal, A.; Cokkinides, V.; Singh, G.K.; Cardinez, C.; Ghafoor, A.; Thun, M. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2004, 54, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.S.W.; Mok, T.S.K.; Rebbeck, T.R. Cancer Genomics: Diversity and Disparity Across Ethnicity and Geography. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, D.E.; Osborne, J.R. Disparities in castration-resistant prostate cancer trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1101–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Luckenbaugh, A.N.; Bayley, C.E.; Penson, D.F.; Shu, X. Racial disparities in mortality for patients with prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Cancer 2021, 127, 1517–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Han, X.; Nogueira, L.; Fedewa, S.A.; Jemal, A.; Halpern, M.T.; Yabroff, K.R. Health insurance status and cancer stage at diagnosis and survival in the United States. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 542–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, C.E.; Wheelwright, S.; Harle, A.; Wagland, R. The role of health literacy in cancer care: A mixed studies systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolidon, V.; Eicher, M.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I.; Arditi, C. Inequalities in patients’ experiences with cancer care: The role of economic and health literacy determinants. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, L.X.; Reichman, M.E.; Miller, B.A.; Hankey, B.F.; Singh, G.K.; Lin, Y.D.; Goodman, M.T.; Lynch, C.F.; Schwartz, S.M.; Chen, V.W.; et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: Selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes Control 2009, 20, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.N.; Staples, J.N.; Garcia, C.; Chatfield, L.; Ferriss, J.S.; Duska, L. Are ethnic and racial minority women less likely to participate in clinical trials? Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 157, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loree, J.M.; Anand, S.; Dasari, A.; Unger, J.M.; Gothwal, A.; Ellis, L.M.; Varadhachary, G.; Kopetz, S.; Overman, M.J.; Raghav, K. Disparity of Race Reporting and Representation in Clinical Trials Leading to Cancer Drug Approvals from 2008 to 2018. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, e191870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chornokur, G.; Dalton, K.; Borysova, M.E.; Kumar, N.B. Disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in African American men, affected by prostate cancer. Prostate 2011, 71, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.E.; Puccini, A.; Trufan, S.J.; Sha, W.; Kadakia, K.C.; Hartley, M.L.; Musselwhite, L.W.; Symanowski, J.T.; Hwang, J.J.; Raghavan, D. Impact of Sociodemographic Disparities and Insurance Status on Survival of Patients with Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Oncologist 2021, 26, e1730–e1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D.; Lloyd, J.E. Understanding and Responding to Health Literacy as a Social Determinant of Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfer, E.A. Health Justice: A Framework (and Call to Action) for the Elimination of Health Inequity and Social Injustice. Am. Univ. Law Rev. 2015, 65, 275–351. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129 (Suppl. S2), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, K.I.; Wiedt, T.L.; Daniels, E.C.; Yabroff, K.R.; Guerra, C.E.; Wender, R.C. Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: A blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruen, R.L.; Pearson, S.D.; Brennan, T.A. Physician-citizens--public roles and professional obligations. JAMA 2004, 291, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yabroff, K.R.; Gansler, T.; Wender, R.C.; Cullen, K.J.; Brawley, O.W. Minimizing the burden of cancer in the United States: Goals for a high-performing health care system. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penman-Aguilar, A.; Talih, M.; Huang, D.; Moonesinghe, R.; Bouye, K.; Beckles, G. Measurement of Health Disparities, Health Inequities, and Social Determinants of Health to Support the Advancement of Health Equity. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2016, 22 (Suppl. S1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.A.; Egerter, S.A.; Woolf, S.H.; Marks, J.S. When do we know enough to recommend action on the social determinants of health? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Egerter, S.; Williams, D.R. The social determinants of health: Coming of age. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.S.; Galanter, J.; Thakur, N.; Pino-Yanes, M.; Barcelo, N.E.; White, M.J.; de Bruin, D.M.; Greenblatt, R.M.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Wu, A.H.B.; et al. Diversity in Clinical and Biomedical Research: A Promise Yet to Be Fulfilled. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Z.D.; Krieger, N.; Agénor, M.; Graves, J.; Linos, N.; Bassett, M.T. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albain, K.S.; Unger, J.M.; Crowley, J.J.; Coltman, C.A.J.; Hershman, D.L. Racial disparities in cancer survival among randomized clinical trials patients of the Southwest Oncology Group. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L.A.; Griffith, K.A.; Jatoi, I.; Simon, M.S.; Crowe, J.P.; Colditz, G.A. Meta-analysis of survival in African American and white American patients with breast cancer: Ethnicity compared with socioeconomic status. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 1342–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Costa, M.V.; Odunlami, A.O.; Mohammed, S.A. Moving upstream: How interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2008, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roetzheim, R.G.; Pal, N.; Tennant, C.; Voti, L.; Ayanian, J.Z.; Schwabe, A.; Krischer, J.P. Effects of health insurance and race on early detection of cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999, 91, 1409–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh-Patel, A.; Morris, C.R.; Kizer, K.W. Disparities in quality of cancer care: The role of health insurance and population demographics. Medicine 2017, 96, e9125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Luo, L.; McLafferty, S. Healthcare access, socioeconomic factors and late-stage cancer diagnosis: An exploratory spatial analysis and public policy implication. Int. J. Public Pol. 2010, 5, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, J.T.; Silver, C.M.; Huang, R.; Hu, Y.; Bentrem, D.J.; Odell, D.D.; Merkow, R.P. Association Between Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities and Hospital Performance in Treatment and Outcomes for Patients with Colon Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, E.B.; Meltzer, J.P.; Bethea, T.N. Health disparities and cancer: Racial disparities in cancer mortality in the United States, 2000–2010. Front. Public Health 2015, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A.; Leavell, J.; Collins, C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conching, A.K.S.; Thayer, Z. Biological pathways for historical trauma to affect health: A conceptual model focusing on epigenetic modifications. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 230, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N.; Wright, E.; Chen, J.T.; Waterman, P.D.; Huntley, E.R.; Arcaya, M. Cancer Stage at Diagnosis, Historical Redlining, and Current Neighborhood Characteristics: Breast, Cervical, Lung, and Colorectal Cancers, Massachusetts, 2001–2015. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 189, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, S.A.; Cole, A.P.; Lu, C.; Marchese, M.; Krimphove, M.J.; Friedlander, D.F.; Mossanen, M.; Kilbridge, K.L.; Kibel, A.S.; Trinh, Q. The impact of underinsurance on bladder cancer diagnosis, survival, and care delivery for individuals under the age of 65 years. Cancer 2020, 126, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L.A.; Kaljee, L.M. Health Disparities and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer in African American Women: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2017, 152, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.A.; Walker, R.J.; Egede, L.E. Associations Between Adverse Childhood Experiences, High-Risk Behaviors, and Morbidity in Adulthood. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.K.; Jemal, A. Socioeconomic and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Cancer Mortality, Incidence, and Survival in the United States, 1950–2014: Over Six Decades of Changing Patterns and Widening Inequalities. J. Environ. Public Health 2017, 2017, 2819372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderwick, H.; Gottlieb, L.M. Meanings and Misunderstandings: A Social Determinants of Health Lexicon for Health Care Systems. Milbank Q. 2019, 97, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N. Epidemiology and the web of causation: Has anyone seen the spider? Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 39, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, C.I.; Gachupin, F.C.; Molina, Y.; Batai, K. Interrogating Patterns of Cancer Disparities by Expanding the Social Determinants of Health Framework to Include Biological Pathways of Social Experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Miller, K.D.; Tossas, K.Y.; Winn, R.A.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 202–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.A.; Chu, K.C.; Hankey, B.F.; Ries, L.A.G. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns among specific Asian and Pacific Islander populations in the U.S. Cancer Causes Control 2008, 19, 227–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.J.; Madan, R.A.; Kim, J.; Posadas, E.M.; Yu, E.Y. Disparities in Cancer Care and the Asian American Population. Oncologist 2021, 26, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, H.P. Cancer in the socioeconomically disadvantaged. CA Cancer J. Clin. 1989, 39, 266–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, D. Social Determinants, Health Literacy, and Disparities: Intersections and Controversies. Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2021, 5, e234–e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, G.C.; Payne-Sturges, D.C. Environmental health disparities: A framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.L.; Riley, P.; Radley, D.C.; McCarthy, D. Closing the Gap: Past Performance of Health Insurance in Reducing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to Care Could Be an Indication of Future Results. Issue Brief 2015, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nash, D.B. Reducing Health Disparities in Underserved Populations: A Spotlight on Health Inequities. Popul. Health Manag. 2022, 25, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, E.N.; Kaatz, A.; Carnes, M. Physicians and implicit bias: How doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, L.; Winn, R.; Hulbert, A. Lung cancer early detection and health disparities: The intersection of epigenetics and ethnicity. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 2498–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.A.; de la Riva, E.E.; Bergan, R.; Norbeck, C.; McKoy, J.M.; Kulesza, P.; Dong, X.; Schink, J.; Fleisher, L. Improving diversity in cancer research trials: The story of the Cancer Disparities Research Network. J. Cancer Educ. 2014, 29, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebbert, R.; Perez, A. Barriers to Clinical Research Participation Among African Americans. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2016, 27, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, M.C.; Price, E.G.; Gary, T.L.; Robinson, K.A.; Gozu, A.; Palacio, A.; Smarth, C.; Jenckes, M.W.; Feuerstein, C.; Bass, E.B.; et al. Cultural competence: A systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med. Care 2005, 43, 356–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G. Culture and the patient-physician relationship: Achieving cultural competency in health care. J. Pediatr. 2000, 136, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.Y. Effectiveness of culturally tailored diabetes interventions for Asian immigrants to the United States: A systematic review. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, G.; Crammond, B.; Malbon, E.; Carey, N. Adaptive Policies for Reducing Inequalities in the Social Determinants of Health. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2015, 4, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, H.D.; Williams, K.M.; Fenton, K.A. From theory to action: Applying social determinants of health to public health practice. Public Health Rep. 2013, 128 (Suppl. S3), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frieden, T.R. A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.E.; Stewart, J. Preface to the biology of disadvantage: Socioeconomic status and health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Gruskin, S. Defining equity in health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Gruskin, S. Poverty, equity, human rights and health. Bull World Health Organ. 2003, 81, 539–545. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, J.R.; Green, A.R.; Carrillo, J.E.; Ananeh-Firempong, O. Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003, 118, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, B.D.; Baicker, K.; Epstein, A.M. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, B.D.; Buchmueller, T.; Decker, S.L.; Carey, C.; Kronick, R. The Affordable Care Act has led to significant gains in health insurance and access to care for young adults. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulte, D.; Jansen, L.; Brenner, H. Disparities in Colon Cancer Survival by Insurance Type: A Population-Based Analysis. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2018, 61, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markt, S.C.; Lago-Hernandez, C.A.; Miller, R.E.; Mahal, B.A.; Bernard, B.; Albiges, L.; Frazier, L.A.; Beard, C.J.; Wright, A.A.; Sweeney, C.J. Insurance status and disparities in disease presentation, treatment, and outcomes for men with germ cell tumors. Cancer 2016, 122, 3127–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.M.W.; Walker, R.; Fujii, M.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Rabin, B.A.; Chubak, J. Financial difficulty, worry about affording care, and benefit finding in long-term survivors of cancer. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 1320–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, N.Y.; Hong, S.; Winn, R.A.; Calip, G.S. Association of Insurance Status and Racial Disparities With the Detection of Early-Stage Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Roche, L.M.; Pawlish, K.S.; Henry, K.A. Cancer survival disparities by health insurance status. Cancer Med. 2013, 2, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levit, L.; Balogh, E.; Nass, S.; Ganz, P.A. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Deliv. High-Qual. Cancer Care; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-309-28660-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, E.; Halpern, M.; Schrag, N.; Cokkinides, V.; DeSantis, C.; Bandi, P.; Siegel, R.; Stewart, A.; Jemal, A. Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2008, 58, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, M.; Schlichting, J.; Chioreso, C.; Ward, M.; Vikas, P. Challenges of Rural Cancer Care in the United States. Oncology 2015, 29, 633–640. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.C.; Bruinooge, S.S.; Kirkwood, M.K.; Olsen, C.; Jemal, A.; Bajorin, D.; Giordano, S.H.; Goldstein, M.; Guadagnolo, B.A.; Kosty, M.; et al. Association between Geographic Access to Cancer Care, Insurance, and Receipt of Chemotherapy: Geographic Distribution of Oncologists and Travel Distance. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3177–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.E.; Holman, C.D.J.; Wisniewski, Z.S.; Semmens, J. Prostate cancer: Socio-economic, geographical and private-health insurance effects on care and survival. BJU Int. 2005, 95, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, A.G.; O’Brien, K.; Saha, S. African American experiences in healthcare: “I always feel like I’m getting skipped over”. Health Psychol. 2016, 35, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaa, K.L.; Roter, D.L.; Biesecker, B.B.; Cooper, L.A.; Erby, L.H. Genetic counselors’ implicit racial attitudes and their relationship to communication. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Ryn, M.; Burke, J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 50, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, I.M.; Chen, J.; Soroui, J.S.; White, S. The contribution of health literacy to disparities in self-rated health status and preventive health behaviors in older adults. Ann. Fam. Med. 2009, 7, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M.; Bell, R. Fair society, healthy lives. Public Health 2012, 126 (Suppl. S1), S4–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, N.; Lofters, A.; Michael, S.; Mall, A.; Pinto, A.D.; Rackal, J. Implementing Anti-Racism Interventions in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepucha, K.R.; Fowler, F.J.J.; Mulley, A.G.J. Policy support for patient-centered care: The need for measurable improvements in decision quality. Health Aff. 2004, 23 (Suppl. S2), VAR54–VAR62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onega, T.; Duell, E.J.; Shi, X.; Wang, D.; Demidenko, E.; Goodman, D. Geographic access to cancer care in the U.S. Cancer 2008, 112, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doescher, M.P.; Jackson, J.E. Trends in cervical and breast cancer screening practices among women in rural and urban areas of the United States. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2009, 15, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, A.C.; Ricketts, T.C.; Savitz, L.A. Cancer in rural versus urban populations: A review. J. Rural Health 1992, 8, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Yabroff, K.R.; Deng, L.; Wang, Q.; Perimbeti, S.; Shapiro, C.L.; Han, X. Transportation barriers, emergency room use, and mortality risk among US adults by cancer history. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2023, 115, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, K.E.; Willman, C.; Winn, R. Optimizing the Use of Telemedicine in Oncology Care: Postpandemic Opportunities. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson-White, S.; Conroy, B.; Slavish, K.H.; Rosenzweig, M. Patient navigation in breast cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2010, 33, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasi, G.; Cucciniello, M.; Guerrazzi, C. The role of mobile technologies in health care processes: The case of cancer supportive care. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, W.J.; Chapman, M.V.; Lee, K.M.; Merino, Y.M.; Thomas, T.W.; Payne, B.K.; Eng, E.; Day, S.H.; Coyne-Beasley, T. Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, D.P.; Chetty, U.; O’Donnell, P.; Gajria, C.; Blackadder-Weinstein, J. Implicit bias in healthcare: Clinical practice, research and decision making. Future Healthc. J. 2021, 8, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Parker, R.M.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Nielsen-Bohlman, L.T.; Rudd, R.R. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005, 20, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volandes, A.E.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K. Health literacy, health inequality and a just healthcare system. Am. J. Bioeth. 2007, 7, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, U.; Mitchell, E.D.; Burgess, C.; Macdonald, S.; Ramirez, A.J. Risk factors for delayed presentation and referral of symptomatic cancer: Evidence for common cancers. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 101 (Suppl. S2), S92–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virnig, B.A.; Baxter, N.N.; Habermann, E.B.; Feldman, R.D.; Bradley, C.J. A matter of race: Early-versus late-stage cancer diagnosis. Health Aff. 2009, 28, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehrer, A.P.; Green, S.R.; Winkfield, K.M. Inequity in Cancer and Cancer Care Delivery in the United States. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2024, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.O.; Green, C.R.; Payne, R. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: Causes and consequences of unequal care. J. Pain 2009, 10, 1187–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, N.J.; Elnahal, S.M.; Alvarez, R.H. Cancer pain: A review of epidemiology, clinical quality and value impact. Future Oncol. 2017, 13, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S. Disparities in cancer outcomes: Lessons learned from children with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2011, 56, 994–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Nogueira, L.; Devasia, T.; Mariotto, A.B.; Yabroff, K.R.; Jemal, A.; Kramer, J.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 409–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamo, C.; Lin, J.J.; Smith, C.; Lurslurchachai, L.; Halm, E.A.; Powell, C.A.; Berman, A.; Schicchi, J.S.; Keller, S.M.; Leventhal, H.; et al. Evaluating beliefs associated with late-stage lung cancer presentation in minorities. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2013, 8, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, M.T.; Ward, E.M.; Pavluck, A.L.; Schrag, N.M.; Bian, J.; Chen, A.Y. Association of insurance status and ethnicity with cancer stage at diagnosis for 12 cancer sites: A retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.B.; Bonomi, M.; Packer, S.; Wisnivesky, J.P. Disparities in lung cancer stage, treatment and survival among American Indians and Alaskan Natives. Lung Cancer 2011, 72, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miser, W.F. Cancer screening in the primary care setting: The role of the primary care physician in screening for breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, ovarian, and prostate cancers. Prim. Care 2007, 34, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbell, E.; Clarke, C.A.; Aravanis, A.M.; Berg, C.D. Modeled Reductions in Late-stage Cancer with a Multi-Cancer Early Detection Test. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telloni, S.M. Tumor Staging and Grading: A Primer. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1606, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, K.; Machida, H.; Shoupe, D.; Melamed, A.; Muderspach, L.I.; Roman, L.D.; Wright, J.D. Ovarian Conservation and Overall Survival in Young Women With Early-Stage Low-Grade Endometrial Cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, I.; Dakwar, A.; Takabe, K. Immunotherapy: Recent Advances and Its Future as a Neoadjuvant, Adjuvant, and Primary Treatment in Colorectal Cancer. Cells 2023, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J.C. Understanding sociodemographic differences in health--the role of fundamental social causes. Am. J. Public Health 1996, 86, 471–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, M.A.; Smedley, B.D. The Unequal Burden of Cancer: An Assessment of NIH Research and Programs for Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; ISBN 9780309514170. [Google Scholar]

- Natale-Pereira, A.; Enard, K.R.; Nevarez, L.; Jones, L.A. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer 2011, 117, 3543–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.N. Patient preferences and health disparities. JAMA 2001, 286, 1506–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.D.; Asch, S.M.; Andersen, R.M.; Hays, R.D.; Shapiro, M.F. Racial and ethnic differences in patients’ preferences for initial care by specialists. Am. J. Med. 2004, 116, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickell, N.A.; Wang, J.J.; Oluwole, S.; Schrag, D.; Godfrey, H.; Hiotis, K.; Mendez, J.; Guth, A.A. Missed opportunities: Racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facione, N.C.; Facione, P.A. Equitable access to cancer services in the 21st century. Nurs. Outlook 1997, 45, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islami, F.; Guerra, C.E.; Minihan, A.; Yabroff, K.R.; Fedewa, S.A.; Sloan, K.; Wiedt, T.L.; Thomson, B.; Siegel, R.L.; Nargis, N.; et al. American Cancer Society’s report on the status of cancer disparities in the United States, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 112–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yin, L.; Lu, C.; Wang, G.; Li, Z.; Sun, F.; Wang, H.; Li, C.; Dai, S.; Lv, N.; et al. Trends in 5-year cancer survival disparities by race and ethnicity in the US between 2002–2006 and 2015–2019. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, D.D.; Waterbor, J.; Hughes, T.; Funkhouser, E.; Grizzle, W.; Manne, U. African-American and Caucasian disparities in colorectal cancer mortality and survival by data source: An epidemiologic review. Cancer Biomark. 2007, 3, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcella, S.; Miller, J.E. Racial differences in colorectal cancer mortality. The importance of stage and socioeconomic status. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001, 54, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, A.v.; Cooney, R.E.; Sabin, M.L. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet 2020, 395, 1243–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquet, C.R.; Commiskey, P.; Daniel Mullins, C.; Mishra, S.I. Recruitment and participation in clinical trials: Socio-demographic, rural/urban, and health care access predictors. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2006, 30, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, J.; Halkitis, P.N. Towards a More Inclusive and Dynamic Understanding of Medical Mistrust Informed by Science. Behav. Med. 2019, 45, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, V.H.; Krumholz, H.M.; Gross, C.P. Participation in cancer clinical trials: Race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA 2004, 291, 2720–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, K.; Weingardt, K.R.; Harris, A.H.S. Influence of subject eligibility criteria on compliance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for inclusion of women, minorities, and children in treatment research. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007, 31, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavers, V.L.; Lynch, C.F.; Burmeister, L.F. Factors that influence African-Americans’ willingness to participate in medical research studies. Cancer 2001, 91, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, C.K. Representation of American blacks in clinical trials of new drugs. JAMA 1989, 261, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, S.R.; Lin, T.A.; Miller, A.B.; Mainwaring, W.; Espinoza, A.F.; Jethanandani, A.; Walker, G.V.; Smith, B.D.; Ashleigh Guadagnolo, B.; Jagsi, R.; et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities among Participants in US-Based Phase 3 Randomized Cancer Clinical Trials. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020, 4, pkaa060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chege, W.; Poddar, A.; Samson, M.E.; Almeida, C.; Miller, R.; Raafat, D.; Fakhouri, T.; Fienkeng, M.; Omokaro, S.O.; Crentsil, V. Demographic Diversity of Clinical Trials for Therapeutic Drug Products: A Systematic Review of Recently Published Articles, 2017–2022. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 64, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, A. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2002, 94, 666–668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.S.J.; Lara, P.N.; Dang, J.H.T.; Paterniti, D.A.; Kelly, K. Twenty years post-NIH Revitalization Act: Enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): Laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual: Renewing the case for enhancing minority participation in cancer clinical trials. Cancer 2014, 120 (Suppl. S7), 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.T.; Watkins, L.; Piña, I.L.; Elmer, M.; Akinboboye, O.; Gorham, M.; Jamerson, B.; McCullough, C.; Pierre, C.; Polis, A.B.; et al. Increasing Diversity in Clinical Trials: Overcoming Critical Barriers. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2019, 44, 148–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkfield, K.M.; Phillips, J.K.; Joffe, S.; Halpern, M.T.; Wollins, D.S.; Moy, B. Addressing Financial Barriers to Patient Participation in Clinical Trials: ASCO Policy Statement. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, JCO1801132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmotzer, G.L. Barriers and facilitators to participation of minorities in clinical trials. Ethn. Dis. 2012, 22, 226–230. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Y.; Schluchter, M.D.; Albrecht, T.L.; Benson, A.B.; Buzaglo, J.; Collins, M.; Flamm, A.L.; Fleisher, L.; Katz, M.; Kinzy, T.G.; et al. Financial Concerns about Participation in Clinical Trials among Patients with Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.A.; Gutiérrez, D.E.; Frausto, J.M.; Al-Delaimy, W.K. Minority Representation in Clinical Trials in the United States: Trends Over the Past 25 Years. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, A.; Diefenbach, M.A.; Doucette, J.; Oh, W.K.; Galsky, M.D. Clinical trial awareness: Changes over time and sociodemographic disparities. Clin. Trials 2015, 12, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, K.; Jabbarpour, Y.; Petterson, S.; Westfall, J.M. State-Level Variation in Primary Care Physician Density. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 104, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klabunde, C.N.; Ambs, A.; Keating, N.L.; He, Y.; Doucette, W.R.; Tisnado, D.; Clauser, S.; Kahn, K.L. The role of primary care physicians in cancer care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livaudais-Toman, J.; Burke, N.J.; Napoles, A.; Kaplan, C.P. Health Literate Organizations: Are Clinical Trial Sites Equipped to Recruit Minority and Limited Health Literacy Patients? J. Health Dispar. Res. Pract. 2014, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rimel, B.J. Clinical Trial Accrual: Obstacles and Opportunities. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.M.; Wilson, C.; Wang, F.; Schillinger, D. Babel babble: Physicians’ use of unclarified medical jargon with patients. Am. J. Health Behav. 2007, 31 (Suppl. S1), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipp, R.D.; Hong, K.; Paskett, E.D. Overcoming Barriers to Clinical Trial Enrollment. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2019, 39, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, M.D. Writing and designing readable patient education materials. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 2004, 31, 373–377. [Google Scholar]

- Pomey, M.; Ghadiri, D.P.; Karazivan, P.; Fernandez, N.; Clavel, N. Patients as partners: A qualitative study of patients’ engagement in their health care. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverri, M.; Anderson, D.; Nápoles, A.M.; Haas, J.M.; Johnson, M.E.; Serrano, F.S.A. Cancer Health Literacy and Willingness to Participate in Cancer Research and Donate Bio-Specimens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, S.M. Enhancing the delivery of cancer care to the disadvantaged: The challenge to providers. Cancer Pract. 1995, 3, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, E.L.; Brownstein, J.N.; Rush, C.H.; Hirsch, G.R.; Willaert, A.M.; Scott, J.R.; Holderby, L.R.; Fox, D.J. Community health workers: Part of the solution. Health Aff. 2010, 29, 1338–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M. The moral problem of health disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100 (Suppl. S1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adashi, E.Y.; Geiger, H.J.; Fine, M.D. Health care reform and primary care—The growing importance of the community health center. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2047–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbrook, R. Disparities in health care—From politics to policy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1486–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B. Health care reform and social movements in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, N.; Kennedy, B.P.; Kawachi, I. Why justice is good for our health: The social determinants of health inequalities. Daedalus 1999, 128, 215–251. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, R.; Stone, J.R.; Hoffman, J.E.; Klappa, S.G. Promoting Community Health and Eliminating Health Disparities Through Community-Based Participatory Research. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, L. Cancer prevention and early detection strategies for reaching underserved urban, low-income black women. Barriers and objectives. Cancer 1993, 72, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, H.P.; Muth, B.J.; Kerner, J.F. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995, 3, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, A.N.; Haidet, P.; Street, R.L.J.; O’Malley, K.J.; Martin, F.; Ashton, C.M. Empowering communication: A community-based intervention for patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2004, 52, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastani, R.; Mojica, C.M.; Berman, B.A.; Ganz, P.A. Low-income women with abnormal breast findings: Results of a randomized trial to increase rates of diagnostic resolution. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2010, 19, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombard, Y.; Baker, G.R.; Orlando, E.; Fancott, C.; Bhatia, P.; Casalino, S.; Onate, K.; Denis, J.; Pomey, M. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnard, K.; Benjamins, M.R.; Hirschtick, J.L.; Castro, M.; Roesch, P.T. Co-Creation of Knowledge: A Community-Based Approach to Multilevel Dissemination of Health Information. Health Promot. Pract. 2021, 22, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delafield, R.; Hermosura, A.N.; Ing, C.T.; Hughes, C.K.; Palakiko, D.; Dillard, A.; Kekauoha, B.P.; Yoshimura, S.R.; Gamiao, S.; Kaholokula, J.K. A Community-Based Participatory Research Guided Model for the Dissemination of Evidence-Based Interventions. Prog. Community Health Partnersh 2016, 10, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, B.F.; Tannan, S.; Anwuri, V.V.; Jackson, S.; Sanford, M.; Tappenden, J.; Goodman, M.S.; Colditz, G.A. A Community-Based Partnership to Successfully Implement and Maintain a Breast Health Navigation Program. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. An Integrated Framework for Assessing the Value of Community-Based Prevention; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, J.R.; Green, A.R.; Carrillo, J.E.; Park, E.R. Cultural competence and health care disparities: Key perspectives and trends. Health Aff. 2005, 24, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govere, L.; Govere, E.M. How Effective is Cultural Competence Training of Healthcare Providers on Improving Patient Satisfaction of Minority Groups? A Systematic Review of Literature. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, A.K.; Lypson, M.L. Beyond cultural competence: Critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad. Med. 2009, 84, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripalani, S.; Bussey-Jones, J.; Katz, M.G.; Genao, I. A prescription for cultural competence in medical education. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 1116–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, J.R. Cultural competence and medical education: Many names, many perspectives, one goal. Acad. Med. 2006, 81, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Guo, K.L. Cultural Diversity Training: The Necessity of Cultural Competence for Health Care Providers and in Nursing Practice. Health Care Manag. 2016, 35, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obama, B. United States Health Care Reform: Progress to Date and Next Steps. JAMA 2016, 316, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hripcsak, G.; Bloomrosen, M.; FlatelyBrennan, P.; Chute, C.G.; Cimino, J.; Detmer, D.E.; Edmunds, M.; Embi, P.J.; Goldstein, M.M.; Hammond, W.E.; et al. Health data use, stewardship, and governance: Ongoing gaps and challenges: A report from AMIA’s 2012 Health Policy Meeting. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2014, 21, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reder, P. Interprofessional Collaboration: From Policy to Practice in Health and Social Care. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 2005, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, J.; Araojo, R.; Thompson, T.; Puckrein, G.A. Integrating Research into Community Practice—Toward Increased Diversity in Clinical Trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1351–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.M.; Nolan, T.S.; Gregory, J.; Joseph, J.J. Diversity in clinical trials: An opportunity and imperative for community engagement. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neta, G.; Sanchez, M.A.; Chambers, D.A.; Phillips, S.M.; Leyva, B.; Cynkin, L.; Farrell, M.M.; Heurtin-Roberts, S.; Vinson, C. Implementation science in cancer prevention and control: A decade of grant funding by the National Cancer Institute and future directions. Implement Sci. 2015, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmquist, B. Equity, Participation, and Power: Achieving Health Justice Through Deep Democracy. J. Law Med. Ethics 2020, 48, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskett, E.D.; Tatum, C.M.; D’Agostino, R.J.; Rushing, J.; Velez, R.; Michielutte, R.; Dignan, M. Community-based interventions to improve breast and cervical cancer screening: Results of the Forsyth County Cancer Screening (FoCaS) Project. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1999, 8, 453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey, L.P.; Phillips, C.W.; Ansell, D.; Whitman, S.; Ebie, N.; Chen, E. An urban community-based cancer prevention screening and health education intervention in Chicago. Public Health Rep. 1989, 104, 536–541. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, R.; Graham, G.; Glied, S.; Meyers, D.; Clancy, C.; Koh, H. Implementing health reform: Improved data collection and the monitoring of health disparities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Colón, V.; Ramos, R.; Davis, J.L.; Escobar, M.; Inda, N.R.; Paige, L.; Palencia, J.; Vives, M.; Grant, C.G.; Green, B.L. Empowering underserved populations through cancer prevention and early detection. J. Community Health 2013, 38, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nipp, R.D.; Lee, H.; Powell, E.; Birrer, N.E.; Poles, E.; Finkelstein, D.; Winkfield, K.; Percac-Lima, S.; Chabner, B.; Moy, B. Financial Burden of Cancer Clinical Trial Participation and the Impact of a Cancer Care Equity Program. Oncologist 2016, 21, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, K.; Evans, L.; Bor, J. The Affordable Care Act Reduced Socioeconomic Disparities in Health Care Access. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.J.; Gabriel, B.A.; Terrell, C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff. 2002, 21, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelblatt, J.S.; Yabroff, K.R.; Kerner, J.F. Equitable access to cancer services: A review of barriers to quality care. Cancer 1999, 86, 2378–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Why health equity? Health Econ. 2002, 11, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyer, R.A.; Hurley, P.; Boehmer, L.; Bruinooge, S.S.; Levit, K.; Barrett, N.; Benson, A.; Bernick, L.A.; Byatt, L.; Charlot, M.; et al. Increasing Racial and Ethnic Diversity in Cancer Clinical Trials: An American Society of Clinical Oncology and Association of Community Cancer Centers Joint Research Statement. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2163–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J.L. Culturally competent health care. Public Health Rep. 2000, 115, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Studies focusing on human populations affected by cancer, particularly those addressing health disparities in marginalized or underserved groups. | Studies not directly related to human cancer or cancer care. |

| Intervention/Exposure | Research examining socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and/or insurance status as primary factors influencing cancer care access, outcomes, or disparities. | Studies that do not primarily investigate socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, or insurance status as factors influencing disparities. |

| Outcomes | Studies reporting on cancer incidence, prevalence, morbidity, mortality, survivorship, quality of life after cancer treatment, screening rates, stage at diagnosis, access to medical resources, or clinical trial participation. | Studies with irrelevant outcomes or those not focused on disparities. |

| Study Design | Original research articles (quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods), systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and relevant policy analyses or reports from recognized health organizations. | Non-empirical articles such as opinion pieces, editorials, commentaries, or conference abstracts (unless specifically sought as the gray literature). |

| Language | English-language publications. | Non-English-language publications. |

| Publication Date | Published between January 2000 and December 2023. Some relevant studies outside this range were selected based on impact. | Publications outside the specified date range. |

| Category | Key Insights |

|---|---|

| Observed Disparities | Black men: Highest rates Native Hawaiians: Higher rates, later diagnosis Asians: Specific cancers like liver and stomach |

| Social Determinants | Lower income, education, and healthcare access in minority communities |

| Healthcare Barriers | More uninsured/underinsured, fewer facilities, implicit bias in care |

| Equity-promoting Strategies | Recruit diverse participants in research, train providers in cultural competence, policy reforms [14,26,59,68] |

| Policy and Practice Recommendations | Improve care access, increase research participation, address social determinants [19,27,30,69,70] |

| Category | Specific Barriers | Type of Barrier | Policy and Intervention Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Competence and Training |

| Cultural/Educational | |

| Policy and Systemic Factors |

| Systemic/Policy | |

| Insurance and Financial Access |

| Financial/Economic |

|

| Geographic and Access Barriers |

| Geographic/Access | |

| Health Literacy and Communication |

| Interpersonal/Communication |

| Aspect of Political Will | Description | Challenges | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment to Health Equity | Political leaders need to prioritize health equity as a central policy objective. | Competing political priorities, lack of sustained focus on marginalized communities. | Advocating for policy agendas that focus on reducing disparities and securing long-term legislative support [166,189,190,192]. |

| Policy Formulation and Legislation | The creation of laws and regulations aimed at expanding access to healthcare, reducing disparities, and promoting inclusion in clinical trials. | Political polarization, insufficient stakeholder engagement, resistance from special interest groups. | Engage cross-party support and ensure stakeholder representation in policy design and implementation [20]. |

| Funding and Resource Allocation | Government funding must be allocated to health programs targeting underserved populations and addressing disparities. | Budget constraints, political reluctance to increase healthcare spending, economic downturns. | Secure bipartisan agreements to prioritize funding for public health, Medicaid expansion, and research inclusion programs [22,69,70]. |

| Long-Term Policy Implementation | Policies should be sustained and institutionalized to ensure ongoing support for healthcare equity. | Policy shifts with changes in administration, lack of enforcement of existing regulations. | Develop bipartisan, long-term strategies for health equity, enforce existing legislation, and ensure continuity across government terms [23,27,30]. |

| Public Accountability and Transparency | Political leaders must be held accountable for the success or failure of health equity initiatives through transparent reporting and data-driven evaluation. | Lack of transparency in data reporting, limited mechanisms for accountability. | Establish independent oversight bodies and require regular reporting on healthcare access, clinical trial inclusion, and disparity reduction efforts. |

| Public Engagement and Advocacy | Political will can be strengthened by engaging the public and raising awareness about healthcare inequities. | Public disengagement, misinformation, and apathy toward healthcare reforms. | Launch public awareness campaigns, facilitate community engagement in policy discussions, and build coalitions to support health equity initiatives [2,18,24,96,143,173,176,180,181,183]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chin, Z.S.; Ghodrati, A.; Foulger, M.; Demirkhanyan, L.; Gondi, C.S. Beyond Barriers: Achieving True Equity in Cancer Care. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060349

Chin ZS, Ghodrati A, Foulger M, Demirkhanyan L, Gondi CS. Beyond Barriers: Achieving True Equity in Cancer Care. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(6):349. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060349

Chicago/Turabian StyleChin, Zaphrirah S., Arshia Ghodrati, Milind Foulger, Lusine Demirkhanyan, and Christopher S. Gondi. 2025. "Beyond Barriers: Achieving True Equity in Cancer Care" Current Oncology 32, no. 6: 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060349

APA StyleChin, Z. S., Ghodrati, A., Foulger, M., Demirkhanyan, L., & Gondi, C. S. (2025). Beyond Barriers: Achieving True Equity in Cancer Care. Current Oncology, 32(6), 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060349