Patient Experiences Regarding Feasibility of Implementing Real-World EQ-5D Collection at an Oncology Centre in Ontario, Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population, Design, and Setting

2.2. Patient Accrual

2.3. Questionnaire Version and Data Capture

2.4. Analysis of Feasibility

2.4.1. Questionnaires

2.4.2. Interviews

- Their overall experience with completing the EQ-5D-3L;

- How the questionnaire is presented (e.g., tablet, paper), and the layout of the questions;

- How often they are asked to complete the EQ-5D-3L;

- How the EQ-5D-3L data will be analyzed.

2.5. Licenses

3. Results

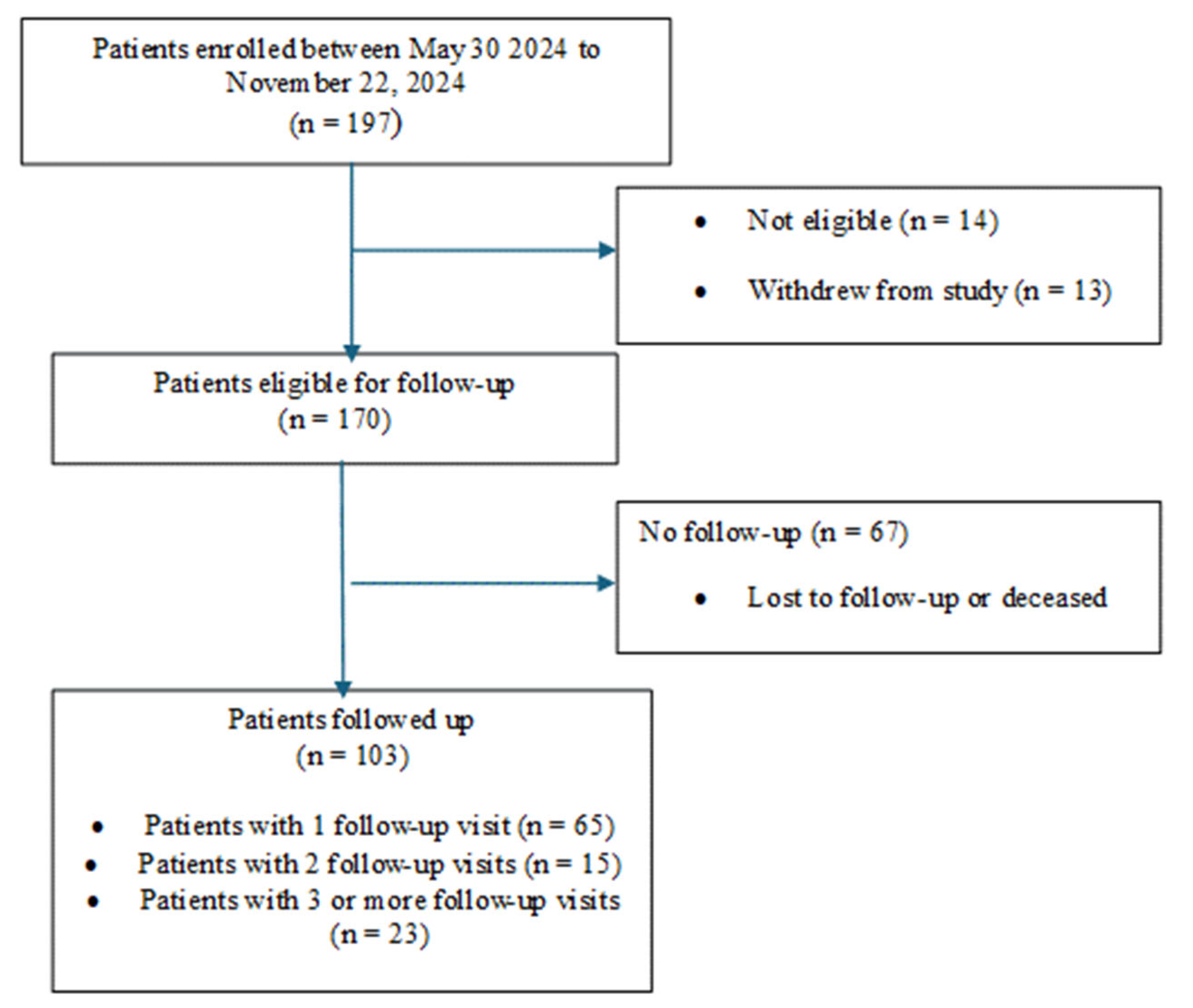

3.1. Patients

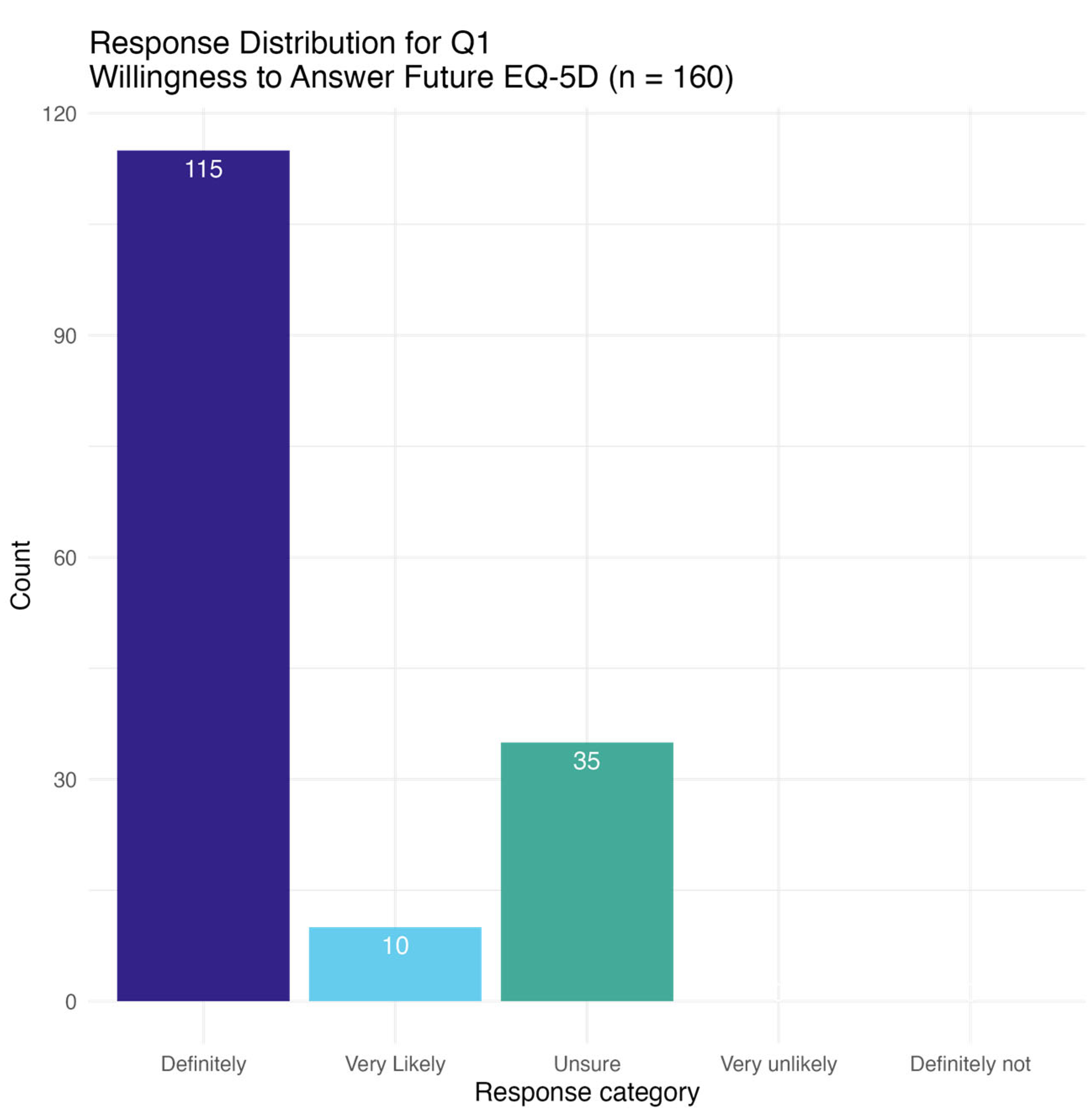

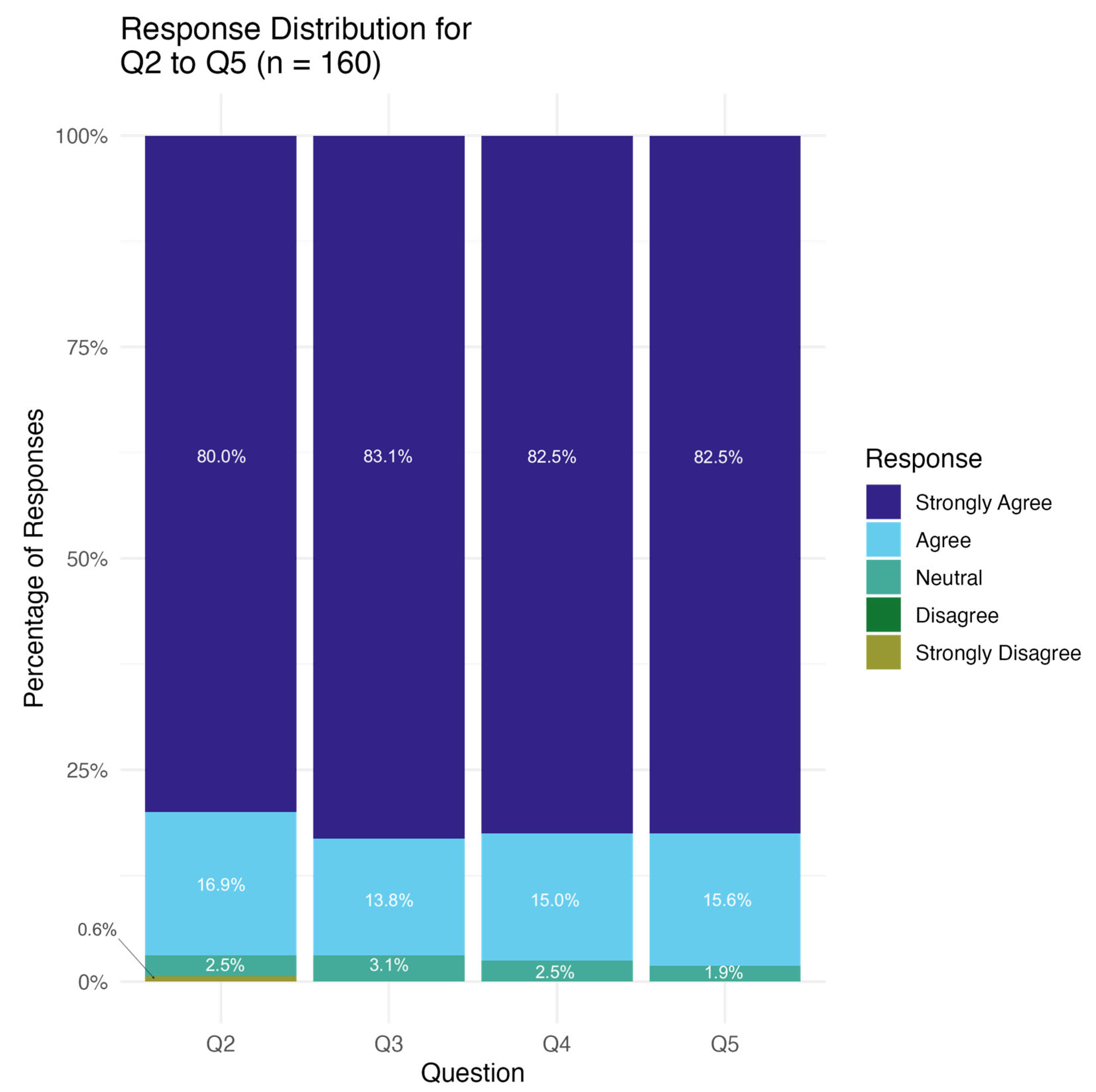

3.2. Questionnaire

3.3. Interviews

3.4. Overall Experience

“If I were in the waiting room… Why are you asking me these questions now if in 2 h I have an allergic reaction, which I did one time”.

“it’s fair to do it. I do think that in the waiting room would be worse than at the end of Chemo”.

“The one benefit of the approach was that you were there in person, so if I had a request for clarifying question, I could ask in the moment versus when you do something online, then it is it’s truly open to interpretation”.

3.4.1. How the Questionnaire Is Presented

3.4.2. Frequency of Administering Questions

3.4.3. How to Analyze and Interpret Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIHI | Canadian Institute for Health Information |

| ESAS | Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| HUs | Health utilities |

| ISAAC | Interactive Symptom Assessment and Collection |

| OH-CCO | Ontario Health-Cancer Care Ontario |

| QALY | Quality-adjusted life year |

| VAS | Visual analogue scale |

| YSM | Your Symptoms Matter |

References

- Boini, S.; Briancon, S.; Guillemin, F.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S. Impact of cancer occurrence on health-related quality of life: A longitudinal pre-post assessment. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2004, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Robinson, L.; Jensen, R.; Smith, T.; Yabroff, K. Factors Associated With Health-Related Quality of Life Among Cancer Survivors in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021, 5, pkaa123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EuroQol Foundation. EQ-5D-3L User Guide; EuroQol Foundation: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wennberg, J.E.; Fisher, E.S.; Skinner, J.S. Geography and the debate over Medicare reform. Health Aff. 2002, W96–W114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, J.; Donaldson, M.S.; Hiatt, R.A. Cancer outcomes research and the arenas of application. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2004, 2004, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. CADTH Methods and Guidelines: Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Canada; CADTH: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marandino, L.; Trastu, F.; Ghisoni, E.; Lombardi, P.; Mariniello, A.; Reale, M.L.; Aimar, G.; Audisio, M.; Bungaro, M.; Caglio, A.; et al. Time trends in health-related quality of life assessment and reporting within publications of oncology randomised phase III trials: A meta-research study. BMJ Oncol. 2023, 2, e000021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, C.M.; Tannock, I.F. Randomised controlled trials and population-based observational research: Partners in the evolution of medical evidence. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalata, P.; Martus, P.; Zettl, H.; Rodel, C.; Hohenberger, W.; Raab, R.; Becker, H.; Liersch, T.; Wittekind, C.; Sauer, R.; et al. Differences between clinical trial participants and patients in a population-based registry: The German Rectal Cancer Study vs. the Rostock Cancer Registry. Dis. Colon. Rectum 2009, 52, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario Cancer Plan IV. Available online: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/sites/ccocancercare/files/assets/CCOOntarioCancerPlan4.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Shaw, C.; Longworth, L.; Bennett, B.; McEntee-Richardson, L.; Shaw, J.W. A Review of the Use of EQ-5D for Clinical Outcome Assessment in Health Technology Assessment, Regulatory Claims, and Published Literature. Patient 2024, 17, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.; Gudex, C.; Kind, P.; Williams, A. A Social Tariff for EuroQol: Results from a UK General Population Survey; University of York: New York, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, N.; Parkin, D.; Janssen, B. (Eds.) Methods for Analysing and Reporting EQ-5D Data; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Sui, M.; Liu, B.; Yang, H.; Liu, R.; Tan, R.L.; Xu, J.; Zheng, E.; Yang, J.; Liu, C.; et al. Measurement Properties of the EQ-5D-5L and EQ-5D-3L in Six Commonly Diagnosed Cancers. Patient 2021, 14, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EuroQol Foundation. EQ-5D Available Versions. Available online: https://euroqol.org/register/obtain-eq-5d/available-versions/#:%7E:text=EQ%2D5D%2D5L%20Interviewer%20Administered%20Proxy%20version%202%3A%20Developed,complete%20a%20paper%2Fdigital%20questionnaire (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Torres, S.; Bayoumi, A.M.; Abrahao, A.B.K.; Trudeau, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Li, C.N.; Mitsakakis, N.; Liu, G.; Krahn, M. Implementing routine collection of EQ-5D-5L in a breast cancer outpatient clinic. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskovitz, M.; Jao, K.; Su, J.; Brown, M.C.; Naik, H.; Eng, L.; Wang, T.; Kuo, J.; Leung, Y.; Xu, W.; et al. Combined cancer patient-reported symptom and health utility tool for routine clinical implementation: A real-world comparison of the ESAS and EQ-5D in multiple cancer sites. Curr. Oncol. 2019, 26, e733–e741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.H.; Wong, E.L.; Jin, J.; Huang, H.; Dong, D. Health-related quality of life measured using EQ-5D in patients with lymphomas. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2549–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorke, J.; Lloyd-Williams, M.; Smith, J.; Blackhall, F.; Harle, A.; Warden, J.; Ellis, J.; Pilling, M.; Haines, J.; Luker, K.; et al. Management of the respiratory distress symptom cluster in lung cancer: A randomised controlled feasibility trial. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 3373–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marten, O.; Brand, L.; Greiner, W. Feasibility of the EQ-5D in the elderly population: A systematic review of the literature. Qual. Life Res. 2022, 31, 1621–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, E.; Algeo, N.; Connolly, D. Feasibility of OptiMaL, a Self-Management Programme for Oesophageal Cancer Survivors. Cancer Control 2023, 30, 10732748231185002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Barbera, L.; Kerrigan, C.L.; Velikova, G. Implementation of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Routine Medical Care. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 2018, 38, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, S.K.; Steinbeck, V.; Busse, R.; Pross, C. Toward System-Wide Implementation of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Framework for Countries, States, and Regions. Value Health 2022, 25, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, L.; Delure, A.; Qi, S.; Link, C.; Chmielewski, L.; Photitai, E.; Smith, L. Utilizing Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in ambulatory oncology in Alberta: Digital reporting at the micro, meso and macro level. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2021, 5, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. CIHI’s PROMs Program. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/patient-reported-outcome-measures-proms/cihis-proms-program (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- BMJ. Chapter 5. Planning and conducting a survey. Epidemiology 2025. Uninitiated. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, A.S.; Kohlmann, T.; Janssen, M.F.; Bonsel, G.; Rosenbloom, S.; Cella, D. Evaluating equivalency between response systems: Application of the Rasch model to a 3-level and 5-level EQ-5D. Med. Care 2007, 45, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hout, B.A.; Shaw, J.W. Mapping EQ-5D-3L to EQ-5D-5L. Value Health 2021, 24, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, M.F.; Bonsel, G.J.; Luo, N. Is EQ-5D-5L Better Than EQ-5D-3L? A Head-to-Head Comparison of Descriptive Systems and Value Sets from Seven Countries. Pharmacoeconomics 2018, 36, 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.F.; Buchholz, I.; Golicki, D.; Bonsel, G.J. Is EQ-5D-5L Better Than EQ-5D-3L Over Time? A Head-to-Head Comparison of Responsiveness of Descriptive Systems and Value Sets from Nine Countries. Pharmacoeconomics 2022, 40, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Participants (N = 170) | |

|---|---|

| Number (%) | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 71 (41.8) |

| Female | 96 (56.5) |

| Not disclosed | 3 (1.8) |

| Age | |

| <50 | 23 (13.5) |

| 50 to 74 | 111 (65.3) |

| 75 to 99 | 32 (18.8) |

| Not disclosed | 4 (2.4) |

| Education | |

| Did not attend College or University | 38 (22.4%) |

| Attended College or University | 127 (74.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (1.8) |

| Not disclosed | 2 (1.2) |

| Primary Cancer Site | |

| Breast | 18 (10.6%) |

| Central nervous system | 1 (0.6%) |

| Colorectal | 12 (7.1%) |

| Genitourinary | 5 (2.9%) |

| Gynecological | 40 (23.5%) |

| Head and Neck | 32 (18.8%) |

| Hematological | 17 (10.0%) |

| Melanoma | 7 (4.1%) |

| Skin | 2 (1.2%) |

| Thoracic | 12 (7.1%) |

| Upper gastrointestinal | 13 (7.6%) |

| Not disclosed | 11 (6.5%) |

| Another current or past primary cancer in last 5 years | |

| Yes | 19 (11.2%) |

| No | 148 (87.1%) |

| Not disclosed | 3 (1.8%) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme and Selected Quotes |

|---|---|

| Overall experience | |

| Straightforward questionnaire | “it’s probably the simplest questionnaire I’ve had to fill out”. |

| Quick completion | “it was simple and fast”. “It only takes a few minutes to fill out the questionnaire… But it still gives you guys an idea of how everybody’s doing, and I think it’s great”. |

| Clinic setting | Positives “I had time on my hands. It was fine”. Negatives Changeability, timing “Why are you asking me these questions now? How does this reflect today, if in 2 h, I have an allergic reaction which I did one time”. |

| Questionnaire content | |

| Oversimplified HRQoL | “I think it was limited to tell you the truth… and it was too fast to capture the pain that we go through, or the discomfort we go through”. “I guess it’s just when I when I know someone’s gonna talk to me about my quality of life and it boils down to this, I’m like, oh, there’s just so much more. That is my quality of life that I don’t even. What’s this really going to tell you?” |

| Suggestions for questions to include | Should have optional free text box after every question “what I found with my previous chemo now with this one that I was also doing radiation because I couldn’t eat and I couldn’t drink. So that became a real source of stress and anxiety for me as a patient”. |

| Administration form | |

| Electronic-questionnaire sent to patient | “So if you had the ability something electronically. So you know, a quick text that you could do it like in 2 min on your phone”. “I like the idea of it being sent to you versus you having to go on like go online or do it at the hospital when you’re all you know running around”. |

| Paper | “I’d rather see the paper copy and read it myself. So I could understand it better”. “I’m 63. So if you ask me if I prefer paper or electronic chances are I’m going to say, paper”. |

| Layout | |

| Facilitators | |

| No concerns | “…and the layout is equally simple. And there’s a lot of value in that kind of simplicity, because it makes it accessible for a much broader audience”. “I think it was done very well. It was easy for me to read and easy for me to fill out, so I don’t have any feedback regarding changing it. I think it was great”. |

| Barriers | |

| Small font | “The font is small. Well, on my screen. It’s small”. “maybe a little bigger would be good”. |

| Response options | Satisfaction with 3 levels “it’s good to have just 3 answers to the questions, too. So you don’t have a lot to to look at”. Five-point scale could be useful |

| Frequency of administration | Beginning, middle, end “Maybe do one in the beginning, one in the middle, one in the end of their treatment. So then you have the rough estimate”. |

| Data analysis | Influence of the environment Mental health Hospital/institute-specific HRQoL Age |

| Interpretation of results | |

| Knowing what to expect “I would wanna know that it was gonna be bad. and then then but it’s gonna be better”. “quality of life like it’s just good to know if other people are taking the same medications that they’re like functioning as well as I can be, so that I can still do all the things that I have to do”. “It’s it’s very reassuring to know that, you know, if I if I go to a doctor with certain symptoms and say, Oh, yeah, that’s…that’s very common”. | |

| Adaptation “the scale is quite vast. So for somebody like me, I automatically go to the top end of the scale. Even though I have cancer. And somebody says, Well, I’m feeling at 50 because I have cancer. But yet I can do everything. But I feel good in my life. You know what I mean, where I am”. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsui, T.C.O.; Mercer, R.E.; Zhou, E.J.; Desai, R.K.; Chatterjee, S.; Yeung, C.Y.L.; Pullenayegum, E.M.; Chan, K.K.W. Patient Experiences Regarding Feasibility of Implementing Real-World EQ-5D Collection at an Oncology Centre in Ontario, Canada. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060308

Tsui TCO, Mercer RE, Zhou EJ, Desai RK, Chatterjee S, Yeung CYL, Pullenayegum EM, Chan KKW. Patient Experiences Regarding Feasibility of Implementing Real-World EQ-5D Collection at an Oncology Centre in Ontario, Canada. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(6):308. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060308

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsui, Teresa C. O., Rebecca E. Mercer, Elena J. Zhou, Rahul K. Desai, Shreya Chatterjee, Curtis Y. L. Yeung, Eleanor M. Pullenayegum, and Kelvin K. W. Chan. 2025. "Patient Experiences Regarding Feasibility of Implementing Real-World EQ-5D Collection at an Oncology Centre in Ontario, Canada" Current Oncology 32, no. 6: 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060308

APA StyleTsui, T. C. O., Mercer, R. E., Zhou, E. J., Desai, R. K., Chatterjee, S., Yeung, C. Y. L., Pullenayegum, E. M., & Chan, K. K. W. (2025). Patient Experiences Regarding Feasibility of Implementing Real-World EQ-5D Collection at an Oncology Centre in Ontario, Canada. Current Oncology, 32(6), 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060308