Should Fertility Preservation Be Offered to Young Women with Melanoma Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors? A SWOT Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Biological Rationale and Clinical Evidence

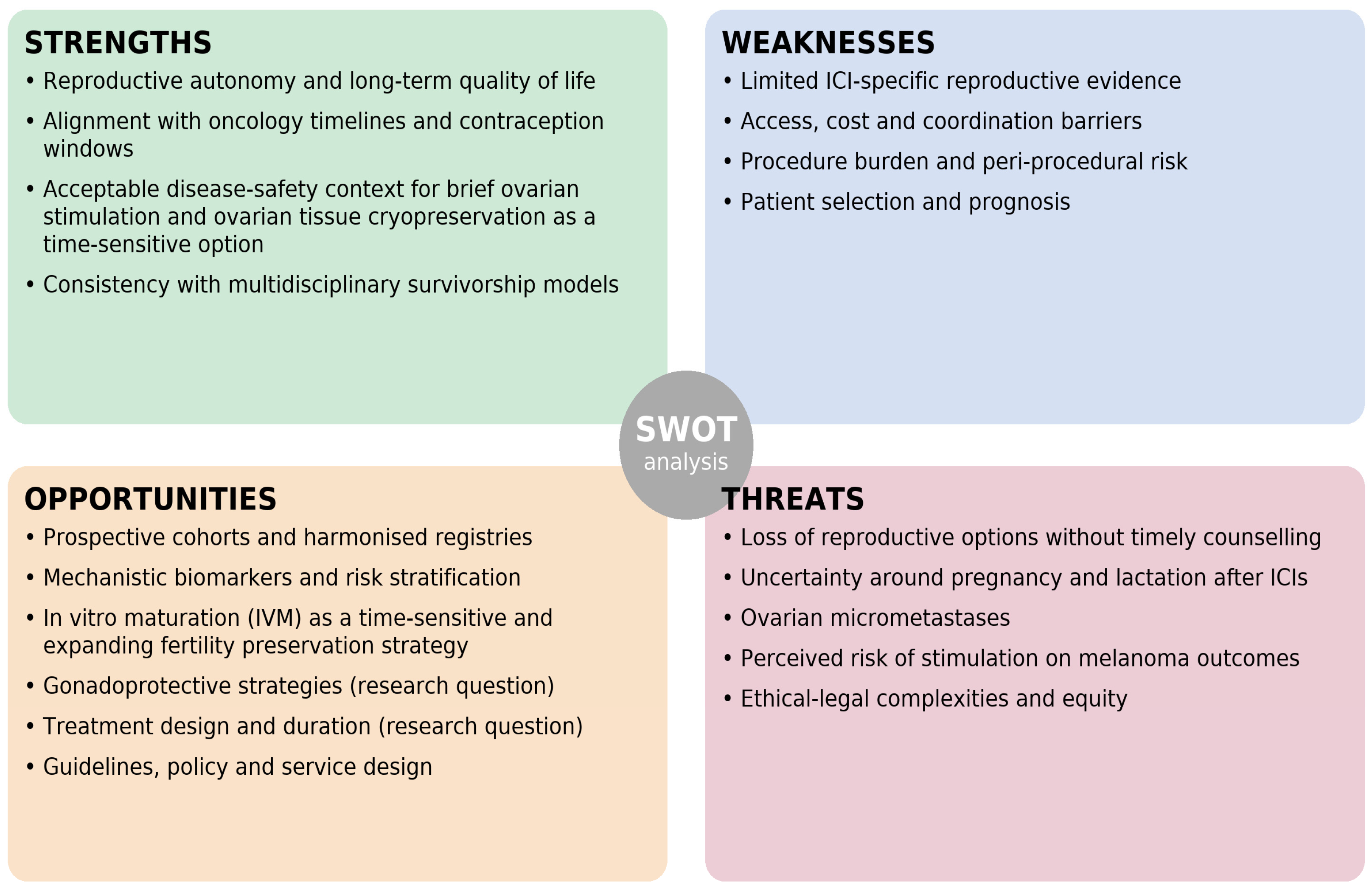

4. SWOT Analysis

4.1. Strengths

4.1.1. Reproductive Autonomy and Long-Term Quality of Life

4.1.2. Alignment with Oncology Timelines and Contraception Windows

4.1.3. Acceptable Disease-Safety Context for Brief Ovarian Stimulation and Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation as a Time-Sensitive Option

4.1.4. Consistency with Multidisciplinary Survivorship Models

4.2. Weaknesses

4.2.1. Limited ICI-Specific Reproductive Evidence

4.2.2. Access, Cost and Coordination Barriers

4.2.3. Procedure Burden and Peri-Procedural Risk

4.2.4. Patient Selection and Prognosis

4.3. Opportunities

4.3.1. Prospective Cohorts and Harmonised Registries

4.3.2. Mechanistic Biomarkers and Risk Stratification

4.3.3. In Vitro Maturation (IVM) as a Time-Sensitive and Expanding Fertility Preservation Strategy

4.3.4. Gonadoprotective Strategies (Research Question)

4.3.5. Treatment Design and Duration (Research Question)

4.3.6. Guidelines, Policy and Service Design

4.4. Threats

4.4.1. Loss of Reproductive Options Without Timely Counselling

4.4.2. Uncertainty Around Pregnancy and Lactation After ICIs

4.4.3. Ovarian Micrometastases

4.4.4. Perceived Risk of Stimulation on Melanoma Outcomes

4.4.5. Ethical-Legal Complexities and Equity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| AFC | Antral follicle count |

| AMH | Anti-Müllerian hormone |

| ART | Assisted reproductive technology |

| ASCO | American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| AYA | Adolescents and young adults |

| COS | Controlled ovarian stimulation |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 |

| ECOG-ACRIN | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group–American College of Radiology Imaging Network |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| ESE | European Society of Endocrinology |

| ESHRE | European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology |

| ESMO | European Society for Medical Oncology |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FET | Frozen embryo transfer |

| FP | Fertility preservation |

| GnRH | Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone |

| GV | Germinal vesicle |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| irAE | Immune-related adverse event |

| IVF | In vitro fertilisation |

| IVM | In vitro maturation |

| MDT | Multidisciplinary team |

| MII | Metaphase II (oocyte stage) |

| OHSS | Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome |

| OTC | Ovarian tissue cryopreservation |

| OTO-IVM | Oocyte in vitro maturation from ovarian tissue |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PI | Prescribing information |

| SmPC | Summary of Product Characteristics |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor-alpha |

References

- Erdmann, F.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Schüz, J.; Zeeb, H.; Greinert, R.; Breitbart, E.W.; Bray, F. International trends in the incidence of malignant melanoma 1953–2008—Are recent generations at higher or lower risk? Int. J. Cancer 2013, 132, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Research, U.K. Melanoma Skin Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/melanoma-skin-cancer (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Keegan, T.H.M.; Ries, L.A.G.; Barr, R.D.; Geiger, A.M.; Vollmer Dahlke, D.; Pollock, B.H.; Bleyer, W.A. National Cancer Institute Next Steps for Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Epidemiology Working Group. Comparison of cancer survival trends in adolescents and young adults and children in the United States. Cancer 2016, 122, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luke, J.J.; Rutkowski, P.; Queirolo, P.; Del Vecchio, M.; Mackiewicz, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; De la Cruz Merino, L.; Khattak, M.A.; Schadendorf, D.; Long, G.V.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage II melanoma (KEYNOTE-716): A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 1718–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, J.; Mandala, M.; Del Vecchio, M.; Gogas, H.J.; Arance, A.M.; Cowey, C.L.; Dalle, S.; Schenker, M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1824–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.P.; Othus, M.; Chen, Y.; Wright, G.P., Jr.; Yost, K.J.; Hyngstrom, J.R.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Lao, C.D.; Fecher, L.A.; Truong, T.G.; et al. Neoadjuvant–adjuvant or adjuvant-only pembrolizumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Schachter, J.; Long, G.V.; Arance, A.; Grob, J.J.; Mortier, L.; Daud, A.; Carlino, M.S.; McNeil, C.; Lotem, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2521–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso-Sousa, R.; Barry, W.T.; Garrido-Castro, A.C.; Hodi, F.S.; Min, L.; Krop, I.E.; Tolaney, S.M.; Keenan, T.; Li, T.; Severgnini, M.; et al. Incidence of endocrine dysfunction following the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torino, F.; Corsello, S.M.; Salvatori, R. Endocrinological side-effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2016, 28, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Filette, J.; Jansen, Y.; Schreuer, M.; Everaert, H.; Velkeniers, B.; Neyns, B.; Bravenboer, B. Incidence of thyroid-related adverse events in melanoma patients treated with pembrolizumab. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 4431–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgadottir, H.; Matikas, A.; Fernebro, J.; Frödin, J.-E.; Ekman, S.; Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A. Fertility and reproductive concerns related to the new generation of cancer drugs and the clinical implication for young individuals undergoing treatments for solid tumors. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 202, 114010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder, E.I.; Othus, M.; Patel, S.P.; Devoe, C.E.; Wright, G.P., Jr.; Yost, K.J.; Hyngstrom, J.R.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Lao, C.D.; Fecher, L.A.; et al. Impact of immune checkpoint inhibition on ovarian reserve in patients with melanoma enrolled in the ECOG-ACRIN E1609 adjuvant trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 12013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Ipilimumab (Yervoy) Product Information; EMA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency. Nivolumab (Opdivo) Product Information; EMA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency. Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) Product Information; EMA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Winship, A.L.; Alesi, L.R.; Sant, S.; Wignall, J.; Kruse, K.; Huang, B.Z.; McKnight, E.; Cutting, C.R.; Wilner, K.D.; Chandler, K.E.; et al. Checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy diminishes oocyte number and quality in mice. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.C.; Luan, Y.; Yu, S.Y.; Xu, J.; Coulter, D.W.; Kim, S.Y. Effects of PD-1 blockade on ovarian follicles in a prepubertal female mouse. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 252, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.A.; Dougan, M. Checking ovarian reserves after checkpoint blockade. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 907–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, F.; Serra, N.; Viganò, P.; Di Guardo, L.; Bersanelli, M.; Massi, D.; Ribas, A.; Ascierto, P.A.; Conte, P.; Dreno, B.; et al. Fertility preservation for patients with melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2022, 32, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, A.; García-Velasco, J.A.; Domingo, J.; Pellicer, A.; Remohí, J. Elective and oncofertility preservation: Factors related to IVF outcomes. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 2222–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, K.H.; Turan, V. Ovarian stimulation and oocyte cryopreservation in females with cancer. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2023, 35, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, M.M.; Donnez, J. Fertility preservation in women for medical and social reasons: Oocytes vs ovarian tissue. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 70, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, J.M.; Ebbel, E.E.; Katz, P.P.; Lee, S.J.; Rosen, M.P.; Smith, J.F.; Nieman, C.L.; Cedars, M.I.; Mertens, A.C.; Partridge, A.H.; et al. Pretreatment fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve quality of life in reproductive-age women with cancer. Cancer 2012, 118, 1710–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, C.; Thom, B.; Kelvin, J.F. Young adult female cancer survivors’ decision regret about fertility preservation. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2015, 4, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Campayo, N.; Paradela de la Morena, S.; Pértega-Díaz, S.; Iglesias Pena, L.; Vihinen, P.; Mattila, K.; Lens, M.B.; Tejera-Vaquerizo, A.; Fonseca, E. Survival of women previously diagnosed of melanoma with subsequent pregnancy: A systematic review and meta analysis and a single center experience. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driscoll, M.S.; Martires, K.; Bieber, A.K.; Pomeranz, M.K.; Grant-Kels, J.M. Pregnancy and melanoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaan, M.; van den Belt-Dusebout, A.W.; Schaapveld, M.; Mooij, T.M.; Burger, C.W.; van Leeuwen, F.E. Melanoma risk after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 1216–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garutti, M.; Lambertini, M.; Puglisi, F. Checkpoint inhibitors, fertility, pregnancy, and sexual life: A systematic review. ESMO Open. 2021, 6, 100276, Erratum in ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, J.; Kwak-Kim, J.; Wang, W. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and reproductive failures. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2023, 156, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerbrun-Cutler, M.T.; Rollo, A.; Gadson, A.; Eaton, J.L. The Status of Fertility Preservation (FP) Insurance Mandates and Their Impact on Utilization and Access to Care. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccatori, F.A.; Azim, H.A., Jr.; Orecchia, R.; Hoekstra, H.J.; Pavlidis, N.; Kesic, V.; Pentheroudakis, G.; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Cancer, pregnancy and fertility: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, vi160–vi170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som, A.; Mandaliya, R.; Alsaadi, D.; Farshidpour, M.; Charabaty, A.; Malhotra, N.; Mattar, M.C.; Zhao, Y.; Choi, W.; Shah, M.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor induced colitis: A comprehensive review. World J. Clin. Cases. 2019, 7, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Sbeih, H.; Ali, F.S.; Wang, Y. Early introduction of selective immunosuppressive therapy associated with favorable clinical outcomes in ICI-induced colitis. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Faleck, D.; Thomas, A.; Harris, J.; Satish, D.; Wang, X.; Charabaty, A.; Ernstoff, M.S.; Glitza Oliva, I.C.; Hanauer, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of vedolizumab and infliximab treatment for immune-mediated diarrhea and colitis in patients with cancer: A two-center observational study. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e003277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, M.; Mortier, L.; Dalle, S.; Dereure, O.; Dalac, S.; Dutriaux, C.; Leccia, M.T.; Maubec, E.; Arnault, J.P.; Brunet Possenti, F.; et al. When to stop immunotherapy for advanced melanoma: The emulated target trials. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 78, 102960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Deavers, M.T.; Silva, E.G.; Malpica, A. Malignant melanoma involving the ovary: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 23 cases. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2004, 23, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.H.; Scully, R.E. Malignant melanoma metastatic to the ovary: A clinicopathologic analysis of 20 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1991, 15, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulou, A.; Korakiti, A.M.; Apostolidou, K.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Zagouri, F. Immune checkpoint inhibitor administration during pregnancy: A case series. ESMO Open. 2021, 6, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). Pembrolizumab; National Library of Medicine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Husebye, E.S.; Castinetti, F.; Criseno, S.; Curigliano, G.; Decallonne, B.; Fleseriu, M.; Higham, C.E.; Lupi, I.; Paschou, S.A.; Toth, M.; et al. Endocrine-related adverse conditions in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibition: An ESE clinical practice guideline. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2022, 187, G1–G21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijers, I.L.M.; Menzies, A.M.; van Akkooi, A.C.J.; Versluis, J.M.; van den Heuvel, N.M.J.; Saw, R.P.M.; Pennington, T.E.; Kapiteijn, E.; van der Veldt, A.A.M.; Suijkerbuijk, K.P.M.; et al. Personalized response directed surgery and adjuvant therapy after neoadjuvant ipilimumab and nivolumab in high risk stage III melanoma: The PRADO trial. Nat Med. 2022, 28, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, Y.J.L.; Rozeman, E.A.; Mason, R.; Goldinger, S.M.; Foppen, M.H.G.; Høejberg, L.; Schmidt, H.; van Thienen, J.; Haanen, J.B.A.G.; Tiainen, L.; et al. Discontinuation of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy in the absence of disease progression or treatment-limiting toxicity: Clinical outcomes in advanced melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1154–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zeijl, M.C.T.; van den Eertwegh, A.J.M.; Wouters, M.W.J.M.; van den Berg, H.P.; Blank, C.U.; Aarts, M.J.B.; Kapiteijn, E.; Aben, K.K.H.; de Vries, E.; Grunhagen, D.J.; et al. Discontinuation of anti-PD-1 monotherapy in advanced melanoma—Outcomes of daily clinical practice. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 150, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gougis, P.; Hamy-Petit, A.-S.; Jochum, F.; Bihan, K.; Basse, C.; Kramkimel, N.; Delyon, J.; Lebrun-Vignes, B.; Funck-Brentano, C.; Salem, J.-E.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Use During Pregnancy and Outcomes in Pregnant Individuals and Newborns. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e245625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. MELAFERT: Impact of Adjuvant Therapy on Fertility in Patients With Resected Melanoma at High Risk of Relapse (NCT07092670). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT07092670 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Lee, C.L.; Martinez, E.; Malon Gimenez, D.; Muniz, T.P.; Butler, M.O.; Saibil, S.D. Female oncofertility and immune checkpoint blockade in melanoma: Where are we today? Cancers 2025, 17, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, C.U.; Lucas, M.W.; Scolyer, R.A.; van de Wiel, B.A.; Menzies, A.M.; Lopez Yurda, M.; Hoeijmakers, L.L.; Saw, R.P.M.; Lijnsvelt, J.M.; Maher, N.G.; et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab and ipilimumab in resectable stage III melanoma (NADINA): A phase 3 trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1696–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, H.; Okazaki, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Nakatani, K.; Hara, M.; Matsumori, A.; Sasayama, S.; Minato, N.; Honjo, T. Autoimmune dilated cardiomyopathy in PD-1 receptor-deficient mice. Science 2001, 291, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dika, E.; Patrizi, A.; Lambertini, M.; Manuelpillai, N.; Fiorentino, M.; Altimari, A.; Ferracin, M.; Lauriola, M.; Fabbri, E.; Campione, E.; et al. Estrogen Receptors and Melanoma: A Review. Cells 2019, 8, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, L.J.; Marcinkiewicz, J.L. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Enhances Oocyte/Follicle Apoptosis in the Neonatal Rat Ovary. Biol. Reprod. 2002, 66, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Kuwahara, A.; Taniguchi, Y.; Yamasaki, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Mukai, Y.; Yamashita, M.; Matsuzaki, T.; Yasui, T.; Irahara, M. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Inhibits Ovulation and Induces Granulosa Cell Death in Rat Ovaries. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2015, 14, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambertini, M.; Peccatori, F.A.; Demeestere, I.; Amant, F.; Wyns, C.; Stukenborg, J.-B.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Halaska, M.J.; Uzan, C.; Meissner, J.; et al. Fertility preservation and post-treatment pregnancies in post-pubertal cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1664–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.I.; Lacchetti, C.; Letourneau, J.; Sharma, R.; Conti, M.; Vajda, Z.; Cheng, Q.; Martin, M.; Feeney, M.; Waller, J.; et al. Fertility preservation in people with cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 1488–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anazodo, A.; Laws, P.; Logan, S.; Saunders, C.; Travaglia, J.; Gerstl, B.; Bradford, N.; Cohn, R.; Birdsall, M.; Barr, R.; et al. The Development of an International Oncofertility Competency Framework: A Model to Increase Oncofertility Implementation. Oncologist 2019, 24, e1450–e1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Prevention of moderate and severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: A guideline. Fertil. Steril. 2024, 121, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.A.; Amant, F.; Braat, D.; D’Angelo, A.; Lopes, S.M.C.d.S.; Demeestere, I.; Dwek, S.; Frith, L.; Lambertini, M.; Maslin, C.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Female fertility preservation. Hum Reprod Open. 2020, 2020, hoaa052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambichler, T.; Susok, L. Uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery under ongoing nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2022, 32, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lliberos, C.; Liew, S.H.; Zareie, P.; La Gruta, N.L.; Mansell, A.; Hutt, K. Evaluation of Inflammation and Follicle Depletion during Ovarian Ageing in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozeman, E.A.; Menzies, A.M.; van Akkooi, A.C.J.; Adhikari, C.; Bierman, C.; van de Wiel, B.A.; Scolyer, R.A.; Krijgsman, O.; Sikorska, K.; Eriksson, H.; et al. Identification of the optimal combination dosing schedule of neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma (OpACIN neo): A multicentre, phase 2, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 948–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Evidence Type | Scope and Inclusion Criteria | Number of Sources (N) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical human studies | Randomized trials and real-world cohorts of immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma; epidemiology and survival in adolescents and young adults; clinical and pathological series on ovarian metastases; endocrine irAEs, ovarian reserve and fertility-related outcomes under ICIs; fertility preservation techniques and utilisation (across cancers and in melanoma); pregnancy and melanoma; pregnancy and lactation after ICIs; ICI-induced colitis and selective immunosuppression; oncofertility implementation studies; ClinicalTrials.gov record of the ongoing MELAFERT trial | 41 | [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,12,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] |

| Pre-clinical/animal and mechanistic studies | Murine and rat models exploring PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, immune-related cardiomyopathy, tumour necrosis factor-α–mediated oocyte/follicle apoptosis, and inflammation-associated follicle depletion in the ovary, used to infer potential mechanisms of gonadotoxicity under immune checkpoint inhibition. | 6 | [16,17,48,49,50,51] |

| Guidelines, regulatory documents and practice frameworks | EMA product information for nivolumab, pembrolizumab and ipilimumab; ASCO, ESMO and ESHRE clinical practice guidelines on fertility preservation and on cancer during pregnancy; ASRM guideline on prevention and management of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; endocrine society guideline on immune-related endocrine AEs; LactMed monograph on pembrolizumab; | 11 | [11,13,14,15,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] |

| SWOT Section | Main Clinical Synthesis and Implications |

|---|---|

| Strengths | Autonomy and Feasibility: Early counselling preserves reproductive autonomy. Random-start ovarian stimulation is feasible within the standard post-operative windows of adjuvant therapy (up to ~12 weeks) without delaying treatment. The procedure is considered oncologically safe as melanoma is not hormone-driven. |

| Weaknesses | Specific Evidence Gaps and Barriers: Clinical data on ovarian reserve are limited to ipilimumab (ECOG-ACRIN E1609), which is not standard adjuvant therapy in Europe, while data on PD-1 inhibitors are lacking. A major barrier is the compressed timeline in emerging neoadjuvant settings, where systemic therapy is initiated at diagnosis, leaving a narrower window for fertility preservation. |

| Opportunities | Prospective Research and Innovation: Ongoing prospective studies (e.g., the MELAFERT trial) are essential to generate real-world evidence on fertility outcomes. Harmonised registries and neoadjuvant platforms offer opportunities to define risk stratification. IVM (In Vitro Maturation) represents a potential time-sensitive strategy for patients with urgent treatment needs. |

| Threats | Missed Care and Uncertainty: The principal threat is the loss of reproductive potential due to delayed referral (“missed opportunities”). Management is complicated by the lack of safety data on pregnancy and lactation during/after ICIs, and by the theoretical risk of ovarian micrometastases in tissue reimplantation strategies. |

| Drug | Contraception During Therapy | Post-Treatment Washout (Minimum) | Breastfeeding Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pembrolizumab | Required | ≥4 months after last dose | Avoid during treatment and for ≥4 months after last dose |

| Nivolumab | Required | ≥5 months after last dose | Avoid during treatment and for ≥5 months after last dose |

| Ipilimumab | Required | ≥3 months after last dose | Avoid during treatment and for ≥3 months after last dose |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raimondo, D.; Miscia, M.; Raffone, A.; Maletta, M.; Cipriani, L.; Marchese, P.V.; Comito, F.; Vicenti, R.; Cortese, F.; Pazzaglia, E.; et al. Should Fertility Preservation Be Offered to Young Women with Melanoma Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors? A SWOT Analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 702. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120702

Raimondo D, Miscia M, Raffone A, Maletta M, Cipriani L, Marchese PV, Comito F, Vicenti R, Cortese F, Pazzaglia E, et al. Should Fertility Preservation Be Offered to Young Women with Melanoma Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors? A SWOT Analysis. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):702. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120702

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaimondo, Diego, Michele Miscia, Antonio Raffone, Manuela Maletta, Linda Cipriani, Paola Valeria Marchese, Francesca Comito, Rossella Vicenti, Federica Cortese, Enrico Pazzaglia, and et al. 2025. "Should Fertility Preservation Be Offered to Young Women with Melanoma Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors? A SWOT Analysis" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 702. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120702

APA StyleRaimondo, D., Miscia, M., Raffone, A., Maletta, M., Cipriani, L., Marchese, P. V., Comito, F., Vicenti, R., Cortese, F., Pazzaglia, E., Bertoldo, L., Cobellis, L., & Seracchioli, R. (2025). Should Fertility Preservation Be Offered to Young Women with Melanoma Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors? A SWOT Analysis. Current Oncology, 32(12), 702. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120702