Supportive Care Needs of Patients with Breast Cancer Who Self-Identify as Black: An Integrative Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

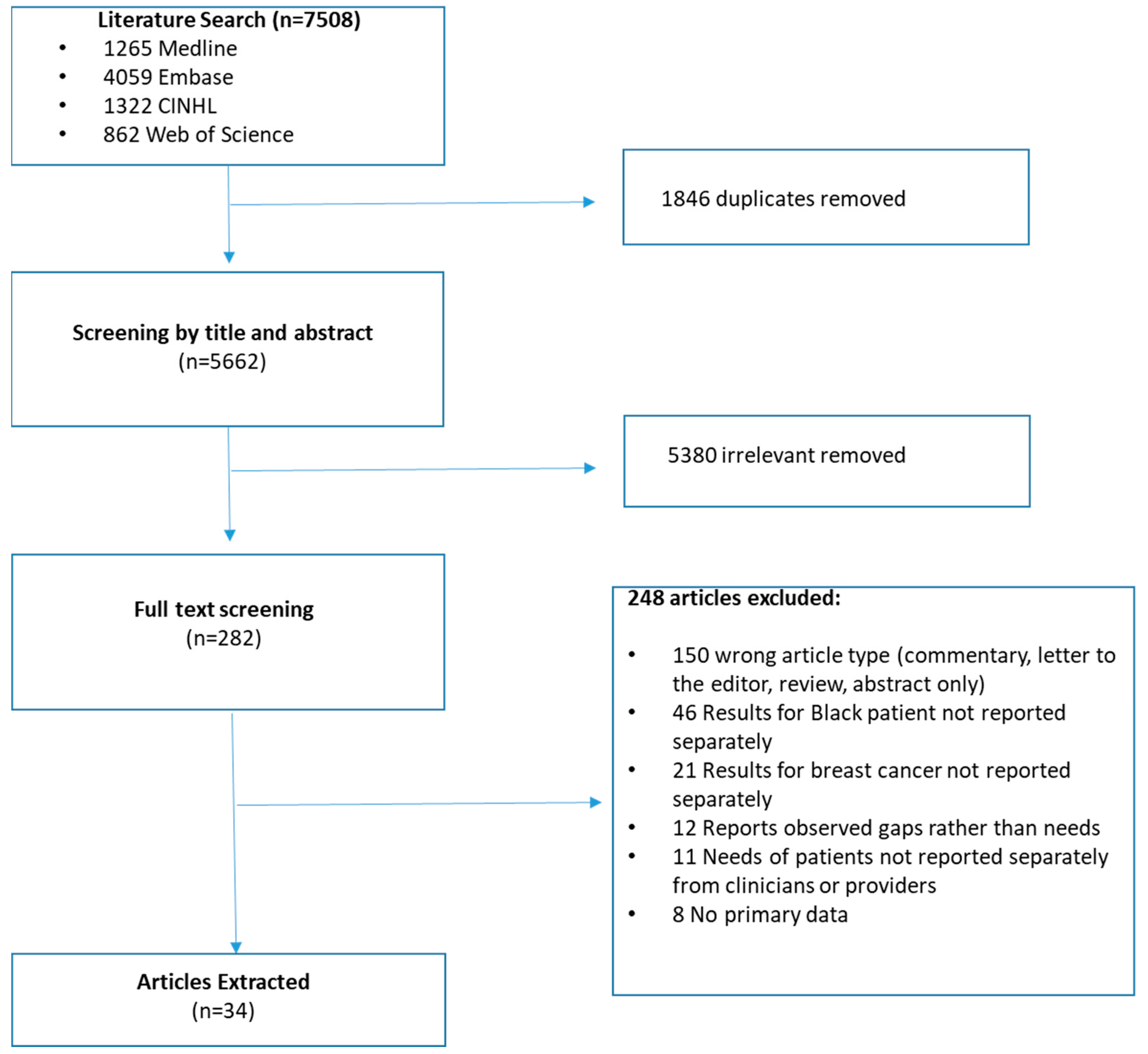

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Details of Retained Articles

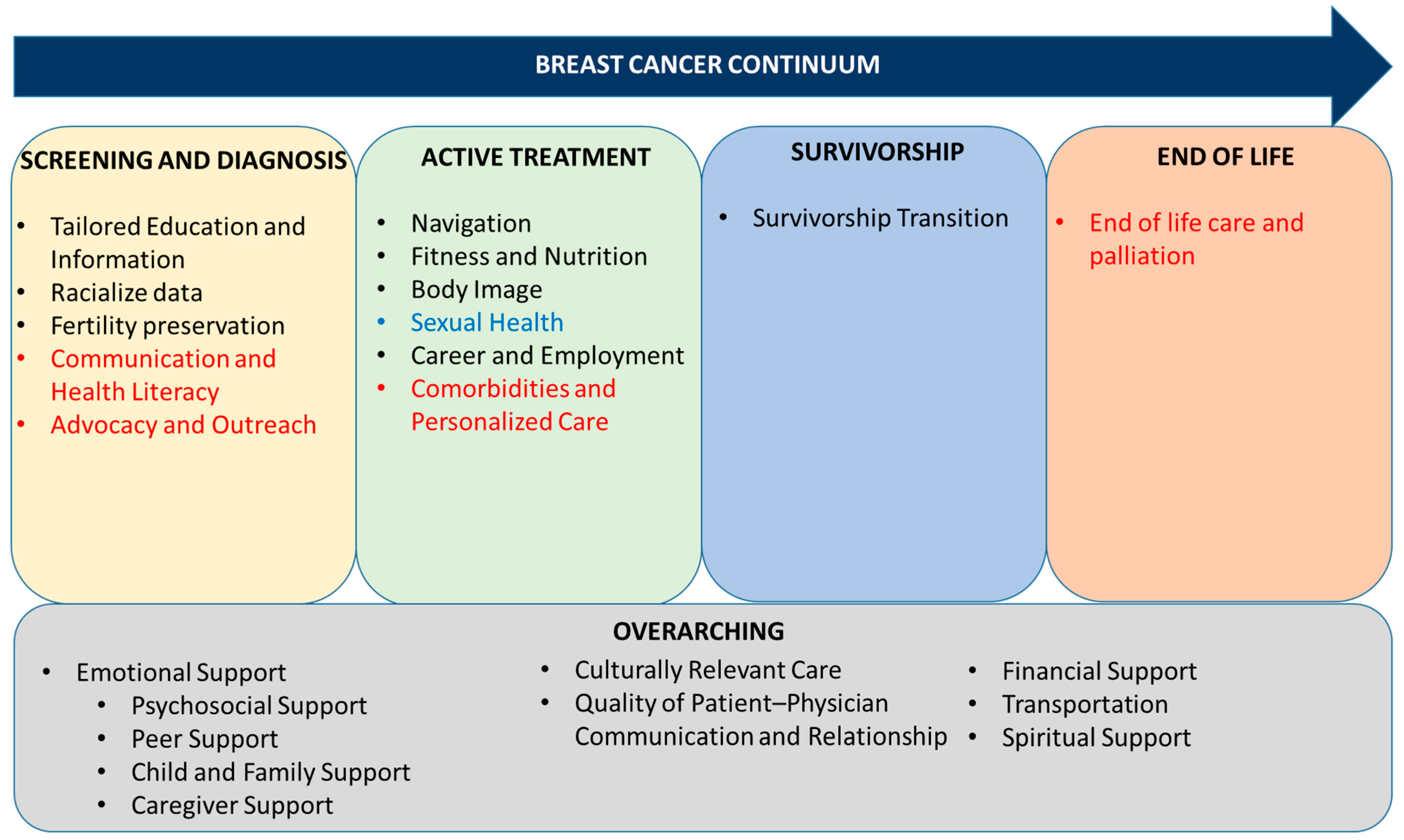

3.2. Supportive Care and Informational Needs Common to the Literature and Nominal Consensus Group (NG)

3.2.1. Overarching Needs

3.2.2. Screening and Diagnosis

3.2.3. Active Treatment

3.2.4. Survivorship

3.2.5. End of Life

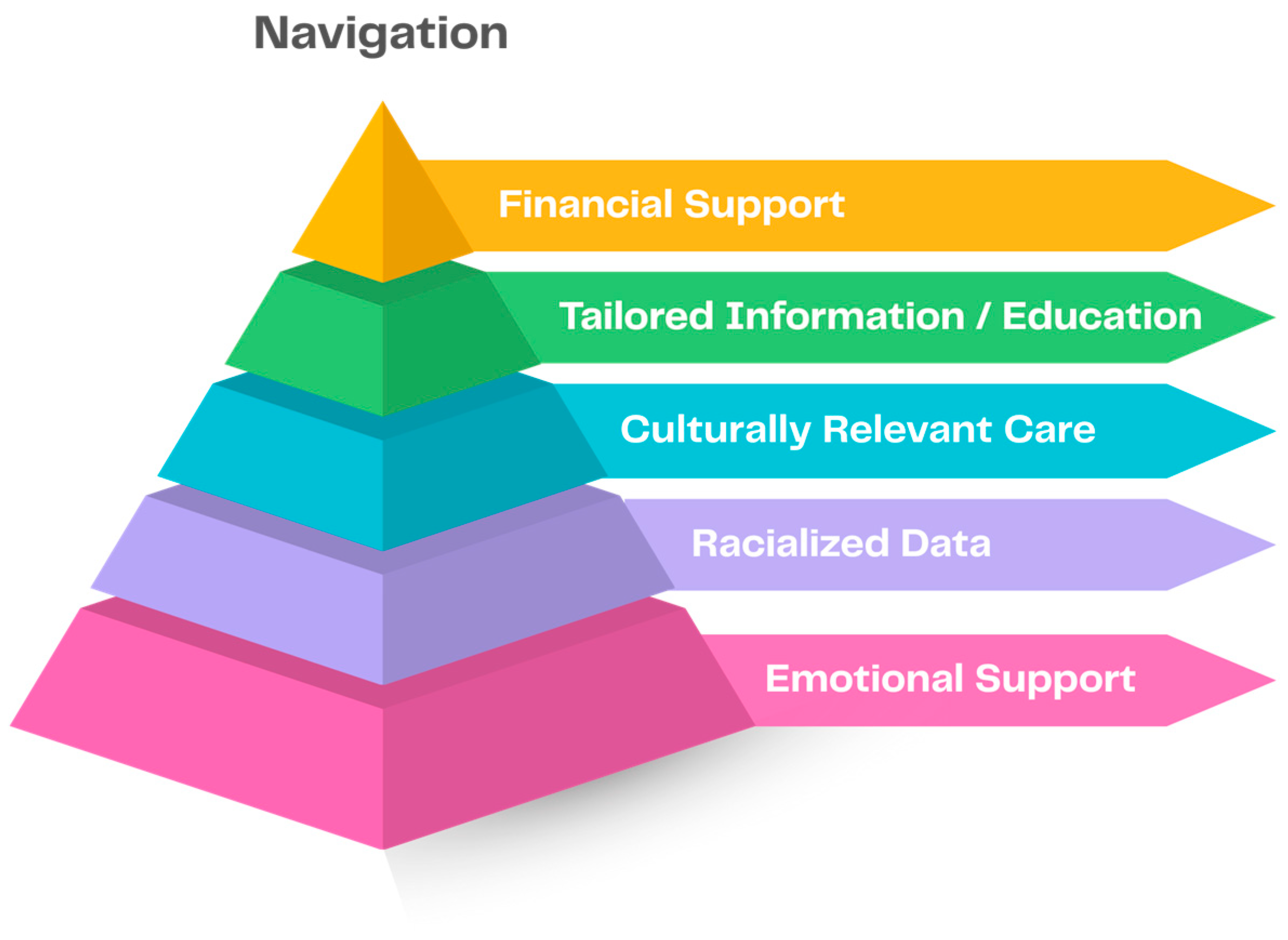

3.3. Prioritization of Supportive Care and Informational Needs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NG | Nominal Consensus Group |

References

- Yedjou, C.G.; Sims, J.N.; Miele, L.; Noubissi, F.; Lowe, L.; Fonseca, D.D.; Alo, R.A.; Payton, M.; Tchounwou, P.B. Health and racial disparity in breast cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1152, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/cancer/breast-cancer.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Canadian Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/breast/statistics (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Howlader, N.; Noone, A.M.; Krapcho, M.; Miller, D.; Brest, A.; Yu, M.; Ruhl, J.; Tatalovich, Z.; Mariotto, A.; Lewis, D.R.; et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2016. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2013–2014. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/cancer-facts-figures-for-african-americans.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Hirko, K.A.; Rocque, G.; Reasor, E.; Taye, A.; Daly, A.; Cutress, R.I.; Copson, E.R.; Lee, D.-W.; Lee, K.-H.; Im, S.-A.; et al. The impact of race and ethnicity in breast cancer—Disparities and implications for precision oncology. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.; Cadiz, S.; Pal, T. Disparities in Genetic Testing and Care among Black women with Hereditary Breast Cancer. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2020, 12, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabellini, N.; Cullen, J.; Cao, L.; Shanahan, J.; Hamerschlak, N.; Waite, K.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Montero, A.J. Racial disparities in breast cancer treatment patterns and treatment related adverse events. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.A.; Collin, L.J.; Kavecansky, J.; Setoguchi, S.; Satagopan, J.M.; Bandera, E.V. Sociodemographic disparities in targeted therapy in ovarian cancer in a national sample. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1104630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggan, K.A.; Rousseau, A.; Halyard, M.; James, S.E.; Kelly, M.; Phillips, D.; Allyse, M.A. “There’s not enough studies”: Views of black breast and ovarian cancer patients on research participation. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 8767–8776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaji, S.; Antony, A.K.; Tonchev, H.; Scichilone, G.; Morsy, M.; Deen, H.; Mirza, I.; Ali, M.M.; Mahmoud, A.M. Racial Disparity in Anthracycline-induced Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer Patients. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadawi, M.; Hussain, Y.; Copeland-Halperin, R.S.; Tobin, J.N.; Moskowitz, C.S.; Dang, C.T.; Liu, J.E.; Steingart, R.M.; Johnson, M.N.; Yu, A.F. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Cardiotoxicity Among Women with HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 147, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, K.A.; O’Dell, W.G.; Tantawy, M.; Casson, C.L.; Ferrall-Fairbanks, M.C.; DeRemer, D.L.; Dungan, J.R.; Nguyen, B.L.; Roumi, N.H.; Shabnaz, S.; et al. Research summary of poster presentations at the 2023 Florida cardio-oncology symposium. Am. Heart J. Plus Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2024, 37, 100348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajal-Ochoa, W.H.; Johnson, D.; Alvarez, A.; Bernal, A.M.; Anampa, J.D. Racial disparities in treatment and outcomes between non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White women with nonmetastatic inflammatory breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 201, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiyaveettil, D.; Joseph, D.; Malik, M. Cardiotoxicity in breast cancer treatment: Causes and mitigation. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2023, 37, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drug Trials Snapshots Summary Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/145718/download (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Pinto, A.D.; Eissa, A.; Kiran, T.; Mashford-Pringle, A.; Needham, A.; Dhalla, I. Considerations for collecting data on race and Indigenous identity during health card renewal across Canadian jurisdictions. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2023, 195, E880–E882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnorom, O.; Findlay, N.; Lee-Foon, N.K.; A Jain, A.; Ziegler, C.P.; E Scott, F.; Rodney, P.; Lofters, A.K. Dying to Learn: A Scoping Review of Breast and Cervical Cancer Studies Focusing on Black Canadian Women. J. Heal. Care Poor Underserved 2019, 30, 1331–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, G.; Ravenell, J.; Crown, A.; DiMaggio, C.; Joseph, K.-A. Impact of Unmet Social Needs on Access to Breast Cancer Screening and Treatment: An Analysis of Barriers Faced by Patients in a Breast Cancer Navigation Program. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 32, 6652–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, M.D.; Patrick-Lake, B.; Abdulai, R.; Broedl, U.C.; Brown, A.; Cohn, E.; Curtis, L.H.; Komelasky, C.; Mbagwu, M.; Mensah, G.A.; et al. Inclusion and diversity in clinical trials: Actionable steps to drive lasting change. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2022, 116, 106740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, O.; Agoke, A.; Sanuth, K.; Fapohunda, A.; Ogunsanya, M.; Piper, M.; Trentham-Dietz, A. Need for Culturally Competent and Responsive Cancer Education for African Immigrant Families and Youth Living in the United States. JMIR Cancer 2024, 10, e53956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridic, G.; Gleason, S.; Ridic, O. Comparisons of health care systems in the United States, Germany and Canada. Mater. Socio-Medica 2012, 24, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.T.; Silva, M.D.; Carvalho, R.d. Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein 2010, 8, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, S.S.; King, M.; Tully, M.P. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2016, 38, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tully, M.P.; Cantrill, J.A. The use of the Nominal group technique in pharmacy practice research: Processes and practicalities. J. Soc. Admin. Pharm. 1997, 14, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, N.; Holmes, C.A. Nominal group technique: An effective method for obtaining group consensus. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2012, 18, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, M.; Gordon, S.; Hamer, P. The Nominal Group Technique: A useful concensus methodology in physiotherapy research. N. Z. J. Physiother. 2004, 32, 126–130. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B.; Oetzel, J.; Minkler, M. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health, 3rd ed.; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Felder, T.M.; Estrada, R.D.; Quinn, J.C.; Phelps, K.W.; Parker, P.D.; Heiney, S.P. Expectations and reality: Perceptions of support among African American breast cancer survivors. Ethn. Health 2019, 24, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.N.; Graff, J.C.; Krukowski, R.A.; Schwartzberg, L.; Vidal, G.A.; Waters, T.M.; Paladino, A.J.; Jones, T.N.; Blue, R.; Kocak, M.; et al. “Nobody Will Tell You. You’ve Got to Ask!”: An Examination of Patient-Provider Communication Needs and Preferences among Black and White Women with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes-Maslow, L.; Allicock, M.; Johnson, L.S. Cancer Support Needs for African American Breast Cancer Survivors and Caregivers. J. Cancer Educ. 2016, 31, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashing-Giwa, K.; Tapp, C.; Brown, S.; Fulcher, G.; Smith, J.; Mitchell, E.; Santifer, R.H.; McDowell, K.; Martin, V.; Betts-Turner, B.; et al. Are survivorship care plans responsive to African-American breast cancer survivors? Voices of survivors and advocates. J. Cancer Surviv. 2013, 7, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashing-Giwa, K.; Ganz, P.A. Understanding the breast cancer experience of African-American women. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 1997, 15, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, N.; Gisiger-Camata, S.; Hardy, C.M.; Thomas, T.F.; Jukkala, A.; Meneses, K. Evaluating Survivorship Experiences and Needs Among Rural African American Breast Cancer Survivors. J. Cancer Educ. 2017, 32, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, E.D.S.; Eng, E.; Randall-David, E.; Robinson, N. Quality-of-Life Concerns of African American Breast Cancer Survivors Within Rural North Carolina: Blending the Techniques of Photovoice and Grounded Theory. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.; Rust, C.; Darby, K. Coping skills among African-American breast cancer survivors. Soc. Work Health Care. 2013, 52, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, P.E.; Sheng, M.; Rhodes, M.M.; Jackson, K.E.; Schover, L.R. Psychosocial Concerns of Young African American Breast Cancer Survivors. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2012, 30, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, K.Z.; Johnson, L.-S.; Samuel-Hodge, C.D.; Gupta, L.; Sundaresan, A.; Nicholson, W.K. Perceived barriers and preferred components for physical activity interventions in African-American survivors of breast or endometrial cancer with type 2 diabetes: The S.U.C.C.E.S.S. framework. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, M.P.; Kissil, K.; Niño, A.; Tubbs, C.Y. “They Paid No Mind to My State of Mind”: African American Breast Cancer Patients’ Experiences of Cancer Care Delivery. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2010, 28, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, A.H.; O’Malley, D.; Barac, A.; Miller, S.M.; Hudson, S.V. Cardiovascular risk and communication among early stage breast cancer survivors. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1360–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control. Available online: https://s22457.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Canadian-Strategy-Cancer-Control-2019-2029-EN.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Wood, T.F.; Murphy, R.A. Tackling financial toxicity related to cancer care in Canada. CMAJ 2024, 196, E297–E298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, H.K.; Bryant, H.; Turner, D.; Coleman, M.P.; Mariotto, A.B.; Spika, D.; Matz, M.; Harewood, R.; Tucker, T.C.; Allemani, C.; et al. Population-Based Cancer Survival in Canada and the United States by Socioeconomic Status: Findings from the CONCORD-2 Study. J. Regist. Manag. 2022, 49, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. The Diversity of the Black Populations in Canada, 2021: A Sociodemographic Portrait. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-657-x/89-657-x2024005-eng.htm (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Collins, S.E.; Clifasefi, S.L.; Stanton, J.; Straits, K.J.; Gil-Kashiwabara, E.; Espinosa, P.R.; Nicasio, A.V.; Andrasik, M.P.; Hawes, S.M.; Miller, K.; et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): Towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, E. Fighting Compassion Fatigue and Burnout by Building Emotional Resilience. Available online: https://www.jons-online.com/issues/2018/december-2018-vol-9-no-12/2152-fighting-compassion-fatigue-and-burnout-by-building-emotional-resilience (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Canadian Cancer Society. HE-24 Breast Cancer Survey & Focus Group Data. Available online: https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/research/for-researchers/funding-opportunities/24-health-equity/summary-of-research-priorities-for-rfa.pdf?rev=9ac204cb24504af9bf6251f1230efc46&hash=B1BED0C76C799C129DA144144133C831 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Rethink Breast Cancer. Uncovered: A Breast Recognition Project. Available online: https://rethinkbreastcancer.com/uncovered (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Baik, S.H.; Gallo, L.C.; Wells, K.J. Patient Navigation in Breast Cancer Treatment and Survivorship: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3686–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-White, S.; Conroy, B.; Slavish, K.H.; Rosenzweig, M. Patient navigation in breast cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2010, 33, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wu, V.S.; Falk, D.; Cheatham, C.; Cullen, J.; Hoehn, R. Patient Navigation in Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 504–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlot, M.; Santana, M.C.; Chen, C.A.; Bak, S.; Heeren, T.C.; Battaglia, T.A.; Egan, A.P.; Kalish, R.; Freund, K.M. Impact of Patient and Navigator Race and Language Concordance on Care after Cancer Screening Abnormalities. Cancer 2015, 121, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, T.; Shah, P.; Weidner, A.; Tezak, A.; Venton, L.; Zuniga, B.; Reid, S.; Cragun, D. Inherited Cancer Knowledge Among Black Females with Breast Cancer Before and After Viewing a Web-Based Educational Video. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2023, 27, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan, G.; Komen Foundation. Patient Navigation Training Program. Available online: https://www.komen.org/about-komen/our-impact/breast-cancer/navigation-nation-training-program/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Canadian Cancer Society. The Cost of Cancer Care. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/get-involved/advocacy/cost-of-cancer (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Wheeler, S.B.; Spencer, J.C.; Pinheiro, L.C.; Carey, L.A.; Olshan, A.F.; Reeder-Hayes, K.E. Financial Impact of Breast Cancer in Black Versus White Women. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1695–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, A.; Ko, N.; Battaglia, T.A.; Chabner, B.A.; Moy, B. Patient Navigation for Underserved Patients Diagnosed with Breast Cancer. Oncologist 2012, 17, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashing, K.T.; Miller, A.M. Assessing the utility of a telephonically delivered psychoeducational intervention to improve health-related quality of life in African American breast cancer survivors: A pilot trial: Telephonic intervention for African American breast cancer survivors. Psycho.-Oncol. 2016, 25, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashing, K.T.; George, M. Exploring the efficacy of a paraprofessional delivered telephonic psychoeducational intervention on emotional well-being in African American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2020, 28, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canie, J.; Tobah, S.; Sanchez, A.-M.; Wathen, C.N. Research with Black Communities to Inform Co-Development of a Framework for Anti-Racist Health and Community Programming. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2025, 57, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrín, O.F.; Nyandege, A.N.; Grafova, I.B.; Dong, X.; Lin, H. Validity of Race and Ethnicity Codes in Medicare Administrative Data Compared With Gold-standard Self-reported Race Collected During Routine Home Health Care Visits. Med. Care 2020, 58, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murengerantwali, S.; Chaachouh, S. Systemic Racism Endures as Quebec Fails to Reckon with Slavery History. Available online: https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/july-2020/systemic-racism (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- McCullough, S.; McRae, M. The Story of Black Slavery in Canadian History. Available online: https://humanrights.ca/story/story-black-slavery-canadian-history (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Race-Based and Indigenous Identity Data Collection and Health Reporting in Canada. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/race-based-and-indigenous-identity-data (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Jamieson, M.; Blair, A.; Jackson, B.; Siddiqi, A. Race-based sampling, measurement and monitoring in health data: Promising practices to address racial health inequities and their determinants in Black Canadians. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2025, 45, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdillahi, I.; Shaw, A. Social Determinants and Inequities in Health for Black Canadians: A Snapshot. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health/social-determinants-inequities-black-canadians-snapshot.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Canadian Public Health Association. Health Equity for Black People and Other People of Colour. Available online: https://www.cpha.ca/health-equity-black-people (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Pardhan, S.; Sehmbi, T.; Wijewickrama, R.; Onumajuru, H.; Piyasena, M.P. Barriers and facilitators for engaging underrepresented ethnic minority populations in healthcare research: An umbrella review. Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, J.; Lee, W.; Choi, E.Y.; Jang, S.G.; Ock, M. Qualitative Research in Healthcare: Necessity and Characteristics. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2023, 56, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, C.; Scott, T.; Schinder, B.; Hager, E.; Friedman, F.S.; Miller, E.; Ragavan, M. Shifting the Paradigm From Participant Mistrust to Researcher & Institutional Trustworthiness: A Qualitative Study of Researchers’ Perspectives on Building Trustworthiness with Black Communities. Community Health Equity Res. Policy 2024, 44, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payán, D.; Zawadzki, M.; Song, A. Advancing community-engaged research to promote health equity: Considerations to improve the field. Perspect. Public Health 2022, 142, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 1997 | 1 (2.9%) |

| 2001 | 3 (8.8%) | |

| 2005 | 1 (2.9%) | |

| 2006 | 2 (5.9%) | |

| 2008 | 1 (2.9%) | |

| 2009 | 1 (2.9%) | |

| 2010 | 2 (5.9%) | |

| 2012 | 1 (2.9%) | |

| 2013 | 2 (5.9%) | |

| 2014 | 2 (5.9%) | |

| 2015 | 1 (2.9%) | |

| 2016 | 2 (5.9%) | |

| 2017 | 4 (11.8%) | |

| 2018 | 3 (8.8%) | |

| 2019 | 1 (2.9%) | |

| 2020 | 2 (5.9%) | |

| 2021 | 2 (5.9%) | |

| Country | United States | 34 (100) |

| Region | South | 15 (44.1) |

| East Coast | 10 (29.4) | |

| West Coast | 3 (8.8%) | |

| Mid-West | 3 (8.8%) | |

| Multiple | 3 (8.8%) | |

| Setting 1 | Urban | 11 (32.4%) |

| Rural | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Both | 2 (5.9%) | |

| Not reported | 20 (58.8%) | |

| Stage of Cancer Continuum 1 | Screening and Diagnosis | 26 (76.5%) |

| Treatment | 24 (70.6%) | |

| Survivorship | 8 (23.5%) | |

| Palliative and End of Life | - | |

| Overarching | 32 (94.1%) |

| Stage of the Cancer Continuum; n (%) | Needs; N (%) | Literature Definition | Summary of Nominal Group Discussion | Nominal Group and Panel Quotes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overarching; 32 (94.1%) | Emotional Support; 27 (79.4%) | Psychosocial Support; 13 (38.2%) | Care that addresses the psychological and social needs of patients [31]. Emotional support describes listening, confiding, mental health, relationships, social functioning, and being present during the cancer experience [31]. |

| “Hospitals need to do better with that emotional and mental support.” “…people need access, especially in our community, to social workers and psychologists and things like that, and it’s tough.” |

| Peer Support; 21 (61.8%) | Emotional, informational, and practical support given by individuals with shared lived experiences to others facing similar health challenges [31]. |

| “Pair people together that are going through treatment that, you know, have similar backgrounds or have been through it already. Just like you’re there to like, ask questions because doctors are telling me that, like, ‘You’re young. It’s going to be good, like you’re going to get through it.’” | ||

| Child and Family Supports; 12 (35.3%) | Support for family and children. This can consist of childcare services, as well as personal support within the home to assist with daily living. It also entails support from family/friends and a desire for longevity to spend time with children/grandchildren and relationships [32]. |

| “…it can really impact family dynamics.” | ||

| Caregivers Supports; 1 (2.9%) | Caregiver support encompasses the emotional, informational, and practical resources that enable caregivers to manage their responsibilities, including access to support groups, knowledge sharing, workplace flexibility, transportation assistance, and help with daily tasks [33]. |

| - | ||

| Culturally Relevant Care; 5 (14.7%) | Culturally relevant care is care that is respectful of and aware of sociological differences that are present in the Black community, which can improve health outcomes and patient satisfaction via shared decision-making and improved healthcare delivery [22,34]. |

| “If you have a family doctor, [they could say], ‘hey, Black women’s [risks] are this, so maybe because of that, you should actually be, you know, screened at 40.’ “…healthcare workers need to be sort of encompass [ing] an anti-racist, anti-oppression lens when dealing with racialized communities” | ||

| Quality of Patient–Physician Communication and Relationship; 12 (35.3%) | High-quality care is characterized by active listening, culturally sensitive communication, and patient involvement in care decisions [32]. |

| “My follow-ups would look like I had no idea. I was like, what happens now? No one was telling me.” “I don’t know what follow-ups are going to look like. So then when I got to meet the new doctor, she’s like, OK, we’re just going to do a yearly follow up on mammogram and like, so I’m going to be getting the same screening as someone that’s in the 40s that hasn’t had breast cancer like, that doesn’t make sense to me. So I had to advocate to get additional screening.” | ||

| Financial Support; 9 (26.5%) | Financial support assists patients in covering the direct and indirect costs of medical care, including treatment expenses, transportation, lost income, and other out-of-pocket costs, aiming to reduce financial stress and improve access to care [34]. |

| “So I’ve been part of this Black organization called CAUFP… they connect financial services professionals within the black community.” | ||

| Transportation; 3 (8.8%) | Having access to transportation for appointments, screening, treatments, or emergencies [31]. Lack of transportation can be a significant barrier for many patients [31,35]. |

| “…if you can’t get to your appointments, then you can’t access care.” | ||

| Spiritual Support; 16 (47.0%) | Care that is respectful of a person’s beliefs, values, and sense of meaning, especially in the context of illness, suffering, or end-of-life [34,35,36]. There is a belief in divine healing and the importance of faith in the face of bad news, as well as the reliance on faith to maintain social standing [35,36]. |

| “So, one of the things I’ve found is that you know there is a big difference in terms of how people get information and sometimes you know whether it’s about literacy or language you know, it’s not one size fits all. There’s also the religious factor here in terms of resources unlike you know, the US where I mean, there are some organizations that you know are specific, like Christian Approach to Cancer Care…” | ||

| Screening and Diagnosis; 26 (76.5%) | Tailored Education and Information; 23 (67.6%) | Providing breast cancer patients with adequate information is essential for quality care [37]. Satisfaction with information is linked to better emotional, functional, and social well-being, improved coping, and higher treatment adherence. It may also strengthen family communication and a sense of competence in managing illness [37,38]. |

| “…access to culturally specific supports such as hair… Our hair is different. Our skin is different. So having all those supports that specifically address our unique differences.” | |

| Racialized Data; 4 (11.8%) | Data for women that are disaggregated by race [32]. Racial discordance in data may result in communication barriers, and these barriers often lead to unequal access to health information and inadequate patient participation in healthcare decision-making, which exacerbate racial disparities in health outcomes [32]. |

| “…availability of data, that speaks to Black people and that there is a lack of sort of racialized data. I think that was an important point to make.” | ||

| Fertility Preservation; 3 (8.8%) | For younger women, cancer treatments may cause premature menopause, infertility, and negative psychosocial effects [39,40]. As such, women considering having children have the option to preserve eggs for future use [39,40]. |

| “As most of us know, within the Black community, children and fertility are definitely valued. Perhaps not being able to have kids after treatment, dealing with that and getting support within the community, I think that definitely has cultural relevance.” | ||

| Communication and Health Literacy—not in literature review | N/A |

| “So one of the things I’ve found is that you know there is a big difference in terms of how people get information and sometimes you know it’s about literacy or language. You know, it’s not one size fits all.” | ||

| Advocacy and Outreach— not in literature review | N/A |

| “…Do you send people who look like them into the community to do the outreach, like where are you advertising? Because it tends to be the case whether it’s organizations or hospitals that they will tend to provide this information to predominantly white women and you know, those things need to change.” | ||

| Active Treatment; 24 (70.6%) | Navigation; 13 (38.2%) | In navigation, the relationship between patients and oncology providers plays a critical role in supporting treatment adherence. Building trustworthy and long-term connections not only encourages patients to complete active treatment but also fosters ongoing engagement in follow-up care [41,42]. |

| “…a physical body to take you through those appointments. And there’s like the navigation of that care.” | |

| Fitness and Nutrition; 9 (26.5%) | Healthy eating and regular physical activity can promote survivorship amongst women with cancer [40]. |

| “…my oncologist was. ‘Oh, don’t exercise. Don’t do this. Don’t do that.’ And just common sense tells me that. OK, but don’t you want to be in your top physical fitness as much as you can before you have surgery? Because I’m thinking it’s gonna really suck if you’re weak and you have surgery.” | ||

| Body Image; 7 (20.6%) | Certain treatments for breast cancer may result in alterations to the body. These changes may impact women’s physical and mental health [40]. |

| “I didn’t feel like every morning I had to be reminded about cancer, every single morning by having to colour in my eyebrows. Cause sometimes you don’t want to talk about cancer.” | ||

| Sexual Health; 6 (17.6%) | Breast cancer treatments can alter the body and reproductive system. Sexual health addresses at how women involve themselves with intimacy and the opportunity to have children [39]. | - | - | ||

| Career and Employment; 1 (2.9%) | Being diagnosed with breast cancer hinders one’s career and employment. An indefinite hiatus from employment can negatively impact one’s financial status and ultimately affect their treatment process [35]. |

| “She had lost her job… it was super stressful because, you know, you’re alone. Her family was in the Caribbean, and you know, now you have to navigate this financial piece.” | ||

| Comorbidities and Personalized care—not in literature review | N/A |

| “…whether it’s the Black community or Latin American community like you know, some other communities of color, there are also other issues in terms of comorbidity. That like, don’t get addressed. So for example, you know diabetes. That’s not factored in in terms of I guess personalized treatment plans? | ||

| Survivorship; 8 (23.5%) | Survivorship Transitions; 8 (23.5%) | Throughout this process of moving from treatment to survivorship, there remains a fear of possible remission [31]. |

| “…you do feel like you have a lot of support during active treatment. Everyone’s there and then like as soon as you’re done active treatment, it’s like literally; I wasn’t even told. Like what my follow-ups would look like, I had no idea- like I was like what happens now? Like no one was telling me.” “…and then like when I was done treatment, it literally felt like it was like you’re done and like you don’t have access to this anymore. And I was like, whoa, this is like, actually, when I really need this support and it just felt like it was not there.” | |

| End of Life; 0 (0%) | End-of-Life Care and Palliation—not in literature review | N/A |

| “All of this needs to you know, be in place from start to finish, even in terms of uh diagnosis, not just you know through journey but all the way through end of life with like specific resources for metastatic care and hospice care and for me, my support came from the African American community, whether was like the Young Survival Coalition or other organizations in the US because I have found, you know, a sense of community there and I felt Accepted.” | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oshinowo, E.; Peterson, E.; Audoin, M.; Ryan, J.; Buckle, J.; Cruickshank, C.; Jones, J.; Kamran, L.M.; Lofters, A.; Russell, P.; et al. Supportive Care Needs of Patients with Breast Cancer Who Self-Identify as Black: An Integrative Review. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100580

Oshinowo E, Peterson E, Audoin M, Ryan J, Buckle J, Cruickshank C, Jones J, Kamran LM, Lofters A, Russell P, et al. Supportive Care Needs of Patients with Breast Cancer Who Self-Identify as Black: An Integrative Review. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(10):580. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100580

Chicago/Turabian StyleOshinowo, Etienne, Emily Peterson, Michelle Audoin, Jennifer Ryan, June Buckle, Clare Cruickshank, Jennifer Jones, Lisa Malinowski Kamran, Aisha Lofters, Patricia Russell, and et al. 2025. "Supportive Care Needs of Patients with Breast Cancer Who Self-Identify as Black: An Integrative Review" Current Oncology 32, no. 10: 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100580

APA StyleOshinowo, E., Peterson, E., Audoin, M., Ryan, J., Buckle, J., Cruickshank, C., Jones, J., Kamran, L. M., Lofters, A., Russell, P., Springer, L., VandeZande, D., Lakey, A., Burnett, L., & Powis, M. (2025). Supportive Care Needs of Patients with Breast Cancer Who Self-Identify as Black: An Integrative Review. Current Oncology, 32(10), 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100580