Assessing and Preparing Patients for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant in Canada: An Environmental Scan of Psychosocial Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Psychosocial Team Composition

3.1.1. Generalist versus Tumour-Specific Team Structure

3.1.2. Demands of Psychosocial Care on Social Workers

3.2. Criteria for Assessing Select HCT Patients

3.2.1. Psychosocial Needs and Risk

3.2.2. Transplant Type and Hospital Provision of Service

3.3. Components and Processes of Pre-HCT Assessments

3.3.1. Common Components of Pre-HCT Assessment

3.3.2. Fluid Process for Biopsychosocial Understanding

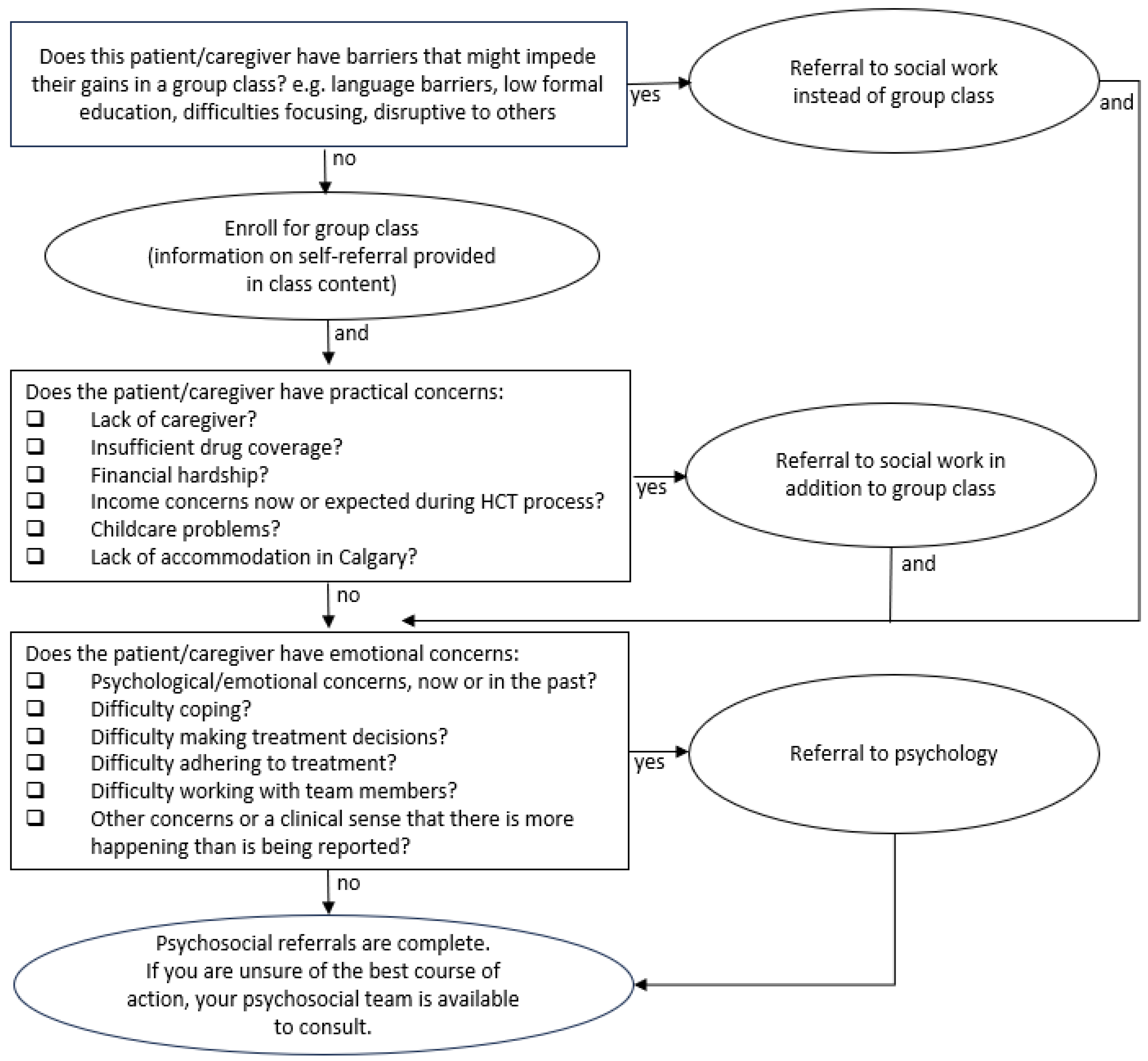

3.4. Design of Patient Education Sessions

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

- What are patient experiences in attending classes, versus 1:1 assessments, versus obtaining support via self-referral, versus being identified and referred by team members?

- Does offering a stepped-care approach optimize the utilization of psychosocial services?

- What are the best ways to evaluate a stepped-care approach? Could they involve semi-structured interviews with patients, caregivers, and health care providers?

- Are there opportunities for interdisciplinary assessments with the medical team?

- Does lack of standardized administration of validated assessment tools contribute to inefficiency, difficulties allocating resources, and, potentially, psychosocial needs being missed?

- Could current non-standardized identification of patients with high psychosocial needs have inclusion or exclusion biases? For example, could minority populations be under-identified? Could stigmatized populations be over-identified? Are patients from diverse cultural backgrounds less likely to receive services based on differing cultural norms in asking for help, power differentials between patients and health care providers, or health literacy?

- The inclusion of patient and caregiver partners in future designs of research studies and educational programs is needed.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCT | Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HCT) |

| Auto | Autologous |

| Allo | Allogeneic |

| SIPAT | Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplant |

| PAIC-HSCT | Psychosocial Assessment Interview of Candidates for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation |

| PACT | Psychosocial Assessment of Candidates for Transplantation |

Appendix A

- (1)

- Who are the members of your BMT psychosocial team? (e.g., social work, psychology, psychiatry)

- (2)

- Does your team offer pre-HCT psychosocial assessments/interviews?

- (a)

- Who are they offered to (i.e., all autos and allos, allos only, high risk individuals).

- (b)

- Is it a standardized assessment?

- (c)

- What questions are routinely asked?

- (d)

- Do you use any questionnaires or standardized assessment tools?

- (e)

- Is anything offered to individuals who do not get a pre-HCT psychosocial assessment?

- (3)

- Do you offer group education classes, pre-transplant?

- (4)

- Any Additional Notes you’d like to add?

References

- Copelan, E.A. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.O.; Giralt, S.A.; Mendoza, T.R.; Brown, J.O.; Neumann, J.L.; Mobley, G.M.; Wang, X.S.; Cleeland, C.S. Symptom burden in patients undergoing autologous stem-cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007, 39, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Guo, S.; Wei, C.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y. Effect of stem cell transplantation of premature ovarian failure in animal models and patients: A meta-analysis and case report. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 15, 4105–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiengthong, K.; Lertjitbanjong, P.; Thongprayoon, C.; Bathini, T.; Sharma, K.; Prasitlumkum, N.; Mao, M.A.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Chokesuwattanaskul, R. Arrhythmias in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Haematol. 2019, 103, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, K.M.; McGinty, H.L.; Cessna, J.; Asvat, Y.; Gonzalez, B.; Cases, M.G.; Small, B.J.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Pidala, J.; Jim, H.S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of changes in cognitive functioning in adults undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 1350–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.; Daly, A.; Jamani, K.; Labelle, L.; Savoie, L.; Stewart, D.; Storek, J.; Beattie, S. Patient eligibility for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A review of patient-associated variables. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019, 54, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevans, M.; El-Jawahri, A.; Tierney, D.K.; Wiener, L.; Wood, W.A.; Hoodin, F.; Kent, E.E.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Lee, S.J.; Hsieh, M.M.; et al. National Institutes of Health hematopoietic cell transplantation late effects initiative: The patient-centered outcomes working group report. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017, 23, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder, D.; Khera, N. Psychosocial and financial issues after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Hematology 2021, 1, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicsák, H.; Ungvari, G.S.; Gazdag, G. Psychosocial aspects of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. World J. Transplant. 2021, 11, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, J.M.; Blanch, J.; Atala, J.; Carreras, E.; Rovira, M.; Cirera, E.; Gastó, C. Psychiatric morbidity and impact on hospital length of stay among hematologic cancer patients receiving stem-cell transplantation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 1907–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, S.; Lebel, S. The experience of caregivers of hematological cancer patients undergoing a hematopoietic stem cell transplant: A comprehensive literature review. Psycho Oncol. 2011, 20, 1137–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillay, B.; Lee, S.J.; Katona, L.; De Bono, S.; Burney, S.; Avery, S. A prospective study of the relationship between sense of coherence, depression, anxiety, and quality of life of haematopoietic stem cell transplant patients over time. Psychooncology 2015, 24, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, J.; Anderson, G.; Kayser, K. Psychosocial Assessment of Candidates for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A National Survey of Centres’ Practices. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amonoo, H.L.; Massey, C.N.; Freedman, M.E.; El-Jawahri, A.; Vitagliano, H.L.; Pirl, W.F.; Huffman, J.C. Psychological considerations in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychosomatics 2019, 60, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.M.; Lyness, J.M.; Sahler, O.J.; Liesveld, J.L.; Moynihan, J.A. Psychosocial factors and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Potential biobehavioral pathways. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 2383–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrijmoet-Wiersma, C.M.J.; Egeler, R.M.; Koopman, H.M.; Norberg, A.L.; Grootenhuis, M.A. Parental stress before, during, and after pediatric stem cell transplantation: A review article. Support. Care Cancer 2009, 17, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, P.; Doucet, S.; Azar, R.; Nagel, D.A.; Boulos, L.; Luke, A.; Mears, K.; Kelly, K.J.; Montelpare, W.J. The use of the environmental scan in health services delivery research: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bultz, B.D.; Groff, S.L.; Fitch, M.; Blais, M.C.; Howes, J.; Levy, K.; Mayer, C. Implementing screening for distress, the 6th vital sign: A Canadian strategy for changing practice. Psycho Oncol. 2011, 20, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Botega, N.J.; De Souza, C.A. A psychosocial assessment interview of candidates for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica 2005, 90, 570–572. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; Rybicki, L.; Corrigan, D.; Dabney, J.; Hamilton, B.K.; Kalaycio, M.; Lawrence, C.; McLellan, L.; Sobecks, R.; Lee, S.J.; et al. Psychosocial Assessment of Candidates for Transplant (PACT) as a tool for psychological and social evaluation of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019, 54, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado, J.R.; Dubois, H.C.; David, E.E.; Sher, Y.; Lolak, S.; Dyal, J.; Witten, D. The Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation (SIPAT): A new tool for the psychosocial evaluation of pre-transplant candidates. Psychosomatics 2012, 53, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talk about What Matters to You—Putting Patients First. Alberta Health Services Website. Available online: http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/frm20338.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Richardson, D.R.; Huang, Y.; McGinty, H.L.; Elder, P.; Newlin, J.; Kirkendall, C.; Andritsos, L.; Benson, D.; Blum, W.; Efebera, Y.; et al. Psychosocial risk predicts high readmission rates for hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018, 53, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macleod, F.; Pink, J.; Beattie, S.; Feldstain, A. Program Evaluation of a Class Addressing Psychosocial Topics in Preparation for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Brief Report. J. Cancer Educ. 2021, 38, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Role | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Worker | |||

| Dedicated to HCT teams | 7 | 63.6% | |

| Available as part of generalist structure/available by consult | 4 | 36.4% | |

| Not available | 0 | 0% | |

| Psychologist | |||

| Dedicated to HCT teams | 2 | 18.2% | |

| Available as part of generalist structure/available by consult | 2 | 18.2% | |

| Not available | 7 | 63.6% | |

| Psychiatrist | |||

| Dedicated to HCT teams | 0 | 0% | |

| Available as part of generalist structure/available by consult | 5 | 45.5% | |

| Not available | 6 | 54.5% | |

| Spiritual Care | |||

| Dedicated to HCT teams | 1 | 9.1% | |

| Available as part of generalist structure/available by consult | 3 | 27.3% | |

| Not available | 7 | 63.6% | |

| Psychosocial Team Composition | |

| Generalist versus Tumour Specific Team Structure | |

| Demands of Psychosocial Care on Social Workers | |

| Criteria for Assessing Select HCT Patients | |

| Psychosocial Needs and Risk | |

| Transplant Type and Hospital Provision of Service | |

| Time and Resources | |

| Components and Processes of Pre-HCT Assessment | |

| Common Components of Pre-HCT Assessments | |

| Fluid Process for Biopsychosocial Understanding | |

| Design and Components of Patient Education Sessions | |

| Mode of Assessment | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients are assessed | 3 | 27.3% | ||

| Select Patients are assessed | ||||

| Allos only | 1 | 9.1% | ||

| All allos and autos with identified higher need | 1 | 9.1% | ||

| Autos only (allos are treated at a different centre) | 1 | 9.1% | ||

| All autos and allos with related donors (unrelated allos are treated at a different centre) | 1 | 9.1% | ||

| Those with high psychosocial needs/risk assessed | 3 | 27.3% | ||

| Most patient have a brief social work assessment for practical needs (not counselling) | 1 | 9.1% | ||

| Approach to Assessment | ||||

| Clinical conversation, not guided by standardized tool | 9 | 81.8 | ||

| Clinical conversation, guided by standardized tool | 2 | 18.1% | ||

| Standardized tool used in standardized manner | 0 | 0% | ||

| Availability of Education Sessions | ||||

| Offered | 4 | 36.4% | ||

| Not offered | 4 | 36.4% | ||

| Data unavailable | 3 | 27.3% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beattie, S.; Qureshi, M.; Pink, J.; Gajtani, Z.; Feldstain, A. Assessing and Preparing Patients for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant in Canada: An Environmental Scan of Psychosocial Care. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 8477-8487. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30090617

Beattie S, Qureshi M, Pink J, Gajtani Z, Feldstain A. Assessing and Preparing Patients for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant in Canada: An Environmental Scan of Psychosocial Care. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(9):8477-8487. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30090617

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeattie, Sara, Maryam Qureshi, Jennifer Pink, Zen Gajtani, and Andrea Feldstain. 2023. "Assessing and Preparing Patients for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant in Canada: An Environmental Scan of Psychosocial Care" Current Oncology 30, no. 9: 8477-8487. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30090617

APA StyleBeattie, S., Qureshi, M., Pink, J., Gajtani, Z., & Feldstain, A. (2023). Assessing and Preparing Patients for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant in Canada: An Environmental Scan of Psychosocial Care. Current Oncology, 30(9), 8477-8487. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30090617