Head and Neck Cancer: A Study on the Complex Relationship between QoL and Swallowing Function

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Cohort

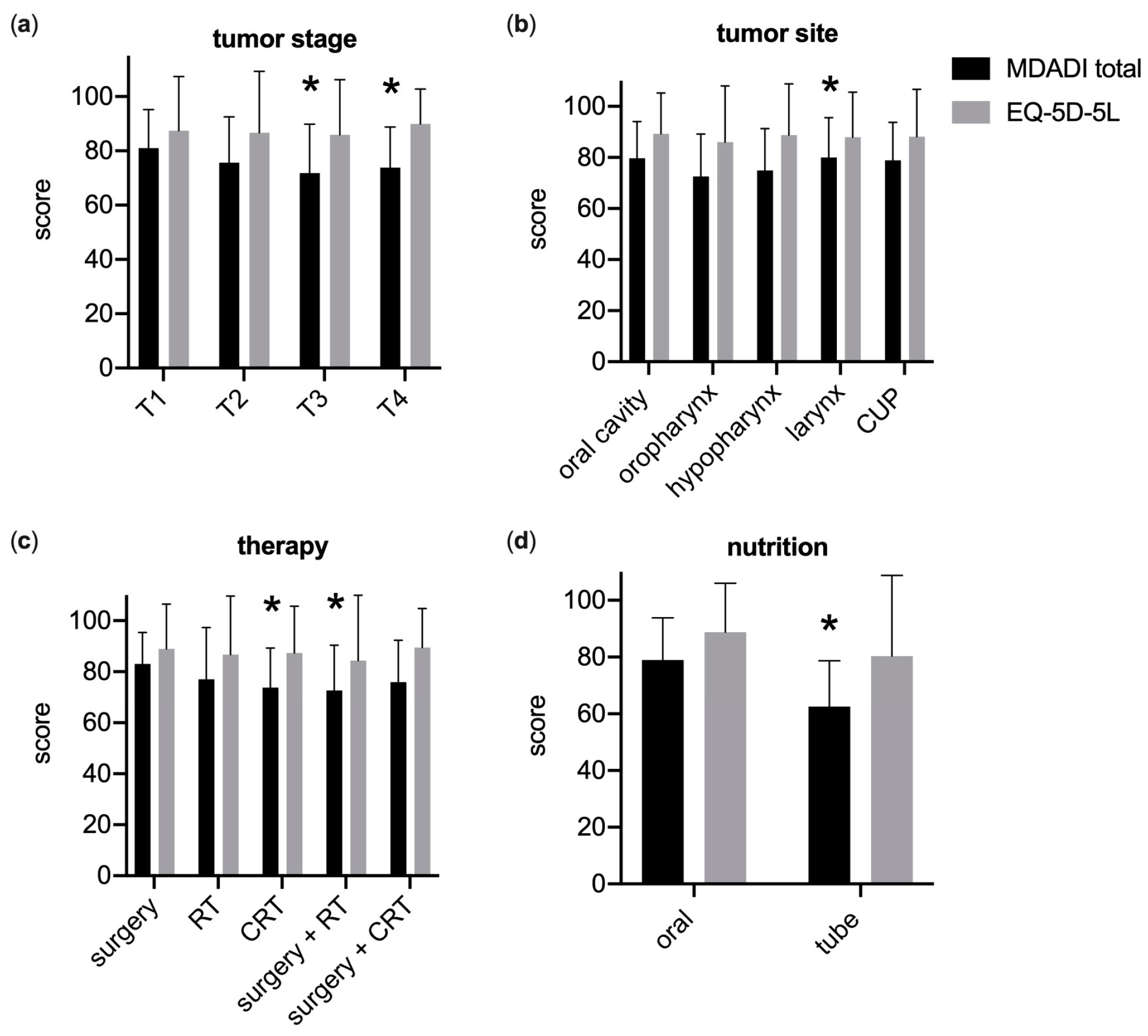

3.2. Generic and Swallowing-Related QoL

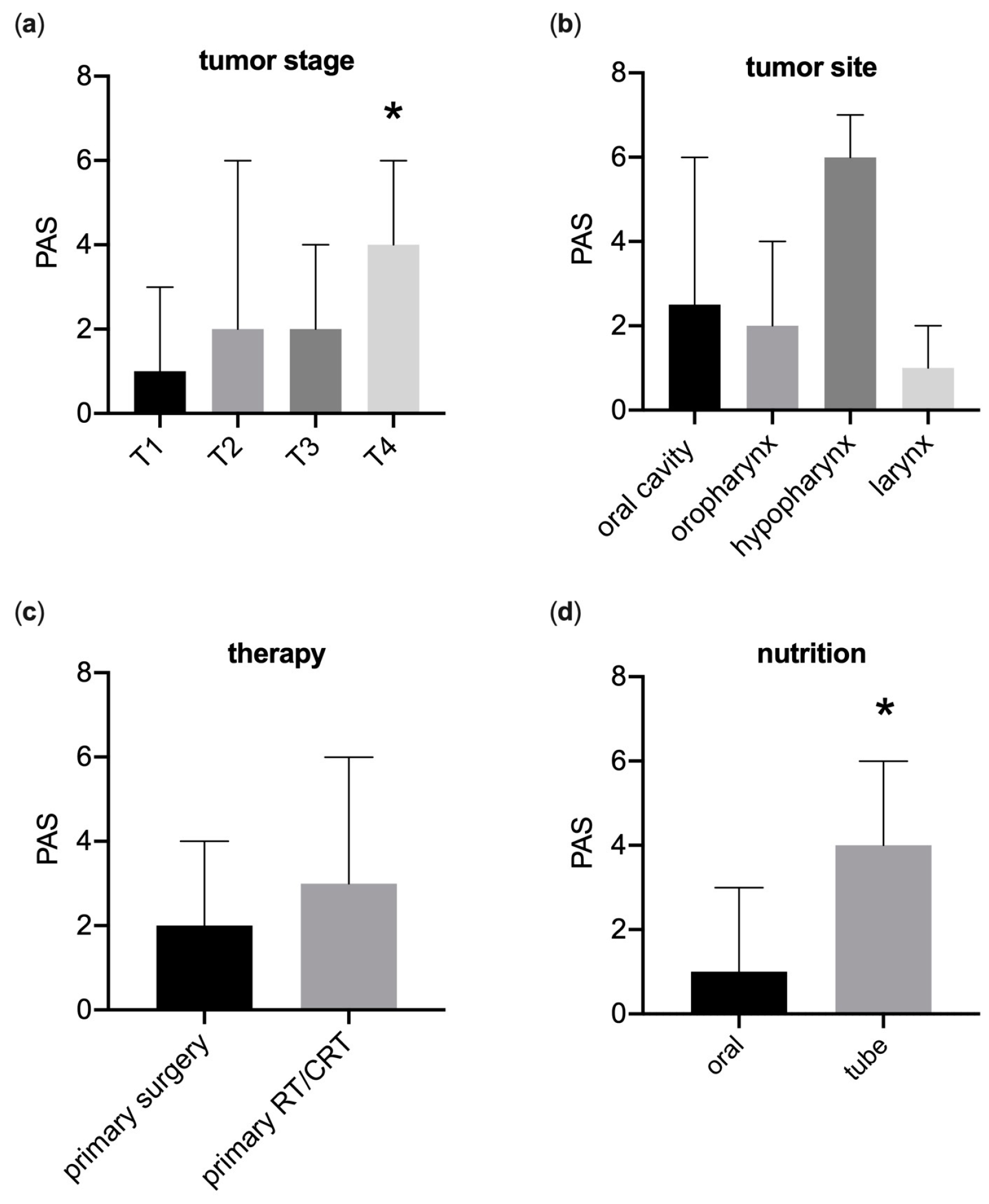

3.3. Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing

3.4. Completion Rates of Digital Questionnaires in Cancer Aftercare

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malone, E.; Siu, L.L. Precision Medicine in Head and Neck Cancer: Myth or Reality? Clin. Med. Insights Oncol. 2018, 12, 1179554918779581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Califano, J.A. Molecular Biology and Immunology of Head and Neck Cancer. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 24, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Specenier, P.; Vermorken, J.B. Optimizing Treatments for Recurrent or Metastatic Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2018, 18, 901–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billard-Sandu, C.; Tao, Y.G.; Sablin, M.P.; Dumitrescu, G.; Billard, D.; Deutsch, E. CDK4/6 Inhibitors in P16/HPV16-Negative Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 277, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, R.; Otero, A.; Jerez, I.; Medina, J.A.; Lupiañez-Pérez, Y.; Gomez-Millan, J. Role of Radiotherapy in the Treatment of Metastatic Head and Neck Cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutcheson, K.A.; Nurgalieva, Z.; Zhao, H.; Gunn, G.B.; Giordano, S.H.; Bhayani, M.K.; Lewin, J.S.; Lewis, C.M. Two-Year Prevalence of Dysphagia and Related Outcomes in Head and Neck Cancer Survivors: An Updated SEER-Medicare Analysis. Head Neck 2019, 41, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisbruch, A. Dysphagia and Aspiration Following Chemo-Irradiation of Head and Neck Cancer: Major Obstacles to Intensification of Therapy. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.P.; Frank, C.; Moltz, C.C.; Vos, P.; Smith, H.J.; Bhamidipati, P.V.; Karlsson, U.; Nguyen, P.D.; Alfieri, A.; Nguyen, L.M.; et al. Aspiration Rate Following Chemoradiation for Head and Neck Cancer: An Underreported Occurrence. Radiother. Oncol. 2006, 80, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.P.; Moltz, C.C.; Frank, C.; Vos, P.; Smith, H.J.; Karlsson, U.; Dutta, S.; Midyett, F.A.; Barloon, J.; Sallah, S. Dysphagia Following Chemoradiation for Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafiz, N.; Mahmoud, D.; Gad, M.; Essa, H.; Morsy, A. Effect of Definitive Hypo-Fractionated Radiotherapy Concurrent with Weekly Cisplatin in Locally Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. J. Med. Life 2023, 16, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, A.C.; Theurer, J.; Prisman, E.; Read, N.; Berthelet, E.; Tran, E.; Fung, K.; de Almeida, J.R.; Bayley, A.; Goldstein, D.P.; et al. Randomized Trial of Radiotherapy Versus Transoral Robotic Surgery for Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Long-Term Results of the ORATOR Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, A.C.; Theurer, J.; Prisman, E.; Read, N.; Berthelet, E.; Tran, E.; Fung, K.; de Almeida, J.R.; Bayley, A.; Goldstein, D.P.; et al. Radiotherapy versus Transoral Robotic Surgery and Neck Dissection for Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ORATOR): An Open-Label, Phase 2, Randomised Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Constantinescu, G.C.; Nguyen, N.T.A.; Jeffery, C.C. Trends in Reporting of Swallowing Outcomes in Oropharyngeal Cancer Studies: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia 2020, 35, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.H.; Spinelli, K.; Marbella, A.M.; Myers, K.B.; Kuhn, J.C.; Layde, P.M. Aspiration, Weight Loss, and Quality of Life in Head and Neck Cancer Survivors. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2004, 130, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauloski, B.R.; Rademaker, A.W.; Logemann, J.A.; Lazarus, C.L.; Newman, L.; Hamner, A.; MacCracken, E.; Gaziano, J.; Stachowiak, L. Swallow Function and Perception of Dysphagia in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Head Neck 2002, 24, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, J.; Palwe, V.; Dutta, D.; Gupta, T.; Laskar, S.G.; Budrukkar, A.; Murthy, V.; Chaturvedi, P.; Pai, P.; Chaukar, D.; et al. Objective Assessment of Swallowing Function After Definitive Concurrent (Chemo)Radiotherapy in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Dysphagia 2011, 26, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florie, M.; Pilz, W.; Kremer, B.; Verhees, F.; Waltman, G.; Winkens, B.; Winter, N.; Baijens, L. EAT-10 Scores and Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing in Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E45–E51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrese, L.C.; Carrau, R.; Plowman, E.K. Relationship Between the Eating Assessment Tool-10 and Objective Clinical Ratings of Swallowing Function in Individuals with Head and Neck Cancer. Dysphagia 2017, 32, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, M.B.; Brodsky, M.B.; Day, T.A.; Lee, F.-S.; Martin-Harris, B. Swallowing-Related Quality of Life After Head and Neck Cancer Treatment. Laryngoscope 2004, 114, 1362–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.; Wilson, J.; McColl, E.; Carding, P.; Patterson, J. Swallowing Outcome Measures in Head and Neck Cancer—How Do They Compare? Oral Oncol. 2016, 52, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.; Lambertsen, K.; Torkov, P.; Dahl, M.; Bonde Jensen, A.; Grau, C. Patient Assessed Symptoms Are Poor Predictors of Objective Findings. Results from a Cross Sectional Study in Patients Treated with Radiotherapy for Pharyngeal Cancer. Acta Oncol. 2007, 46, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsh, E.; Naunheim, M.; Holman, A.; Kammer, R.; Varvares, M.; Goldsmith, T. Patient-reported versus Physiologic Swallowing Outcomes in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer after Chemoradiation. Laryngoscope 2019, 129, 2059–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.M.; Portas, J.; López, R.V.M.; Côrrea, D.F.; Arantes, L.M.R.B.; Carvalho, A.L. Study of Dysphagia in Patients with Advanced Oropharyngeal Cancer Subjected to an Organ Preservation Protocol Based on Concomitant Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedström, J.; Tuomi, L.; Finizia, C.; Olsson, C. Correlations Between Patient-Reported Dysphagia Screening and Penetration–Aspiration Scores in Head and Neck Cancer Patients Post-Oncological Treatment. Dysphagia 2018, 33, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, H.-H.; Tsai, S.-W.; Hsieh, M.H.-C.; Chen, Y.-J.; Hsiao, J.-R.; Huang, C.-C.; Ou, C.-Y.; Chang, C.-C.; Lee, W.-T.; Tsai, S.-T.; et al. Evaluation of Objective and Subjective Swallowing Outcomes in Patients with Dysphagia Treated for Head and Neck Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, K.A.; Kosek, S.R.; Tanner, K. Quality-of-life Scores Compared to Objective Measures of Swallowing after Oropharyngeal Chemoradiation. Laryngoscope 2014, 124, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wishart, L.R.; Harris, G.B.; Cassim, N.; Alimin, S.; Liao, T.; Brown, B.; Ward, E.C.; Nund, R.L. Association Between Objective Ratings of Swallowing and Dysphagia-Specific Quality of Life in Patients Receiving (Chemo)Radiotherapy for Oropharyngeal Cancer. Dysphagia 2022, 37, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Molen, L.; van Rossum, M.A.; Ackerstaff, A.H.; Smeele, L.E.; Rasch, C.R.; Hilgers, F.J. Pretreatment Organ Function in Patients with Advanced Head and Neck Cancer: Clinical Outcome Measures and Patients’ Views. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2009, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogus-Pulia, N.M.; Pierce, M.C.; Mittal, B.B.; Zecker, S.G.; Logemann, J.A. Changes in Swallowing Physiology and Patient Perception of Swallowing Function Following Chemoradiation for Head and Neck Cancer. Dysphagia 2014, 29, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.L.; Flamand, Y.; Weinstein, G.S.; Li, S.; Quon, H.; Mehra, R.; Garcia, J.J.; Chung, C.H.; Gillison, M.L.; Duvvuri, U.; et al. Phase II Randomized Trial of Transoral Surgery and Low-Dose Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy in Resectable P16+ Locally Advanced Oropharynx Cancer: An ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group Trial (E3311). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owadally, W.; Hurt, C.; Timmins, H.; Parsons, E.; Townsend, S.; Patterson, J.; Hutcheson, K.; Powell, N.; Beasley, M.; Palaniappan, N.; et al. PATHOS: A Phase II/III Trial of Risk-Stratified, Reduced Intensity Adjuvant Treatment in Patients Undergoing Transoral Surgery for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yom, S.S.; Torres-Saavedra, P.; Caudell, J.J.; Waldron, J.N.; Gillison, M.L.; Xia, P.; Truong, M.T.; Kong, C.; Jordan, R.; Subramaniam, R.M.; et al. Reduced-Dose Radiation Therapy for HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Carcinoma (NRG Oncology HN002). J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, F.; Seiss, M.; Gräßel, E.; Stelzle, F.; Klotz, M.; Rosanowski, F. Schluckbezogene Lebensqualität Bei Mundhöhlenkarzinomen: Anderson-Dysphagia-Inventory, Deutsche Version. HNO 2010, 58, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutcheson, K.A.; Barrow, M.P.; Lisec, A.; Barringer, D.A.; Gries, K.; Lewin, J.S. What Is a Clinically Relevant Difference in MDADI Scores between Groups of Head and Neck Cancer Patients? Laryngoscope 2016, 126, 1108–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbek, J.C.; Robbins, J.A.; Roecker, E.B.; Coyle, J.L.; Wood, J.L. A Penetration-Aspiration Scale. Dysphagia 1996, 11, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hey, C.; Pluschinski, P.; Zaretsky, Y.; Almahameed, A.; Hirth, D.; Vaerst, B.; Wagenblast, J.; Stöver, T. Penetration-Aspiration Scale According to Rosenbek: Validation of the German Version for Endoscopic Dysphagia Diagnostics. HNO 2014, 62, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, P.D.; Rademaker, A.W.; Leder, S.B. The Yale Pharyngeal Residue Severity Rating Scale: An Anatomically Defined and Image-Based Tool. Dysphagia 2015, 30, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmore, S.E.; Kenneth, S.M.A.; Olsen, N. Fiberoptic Endoscopic Examination of Swallowing Safety: A New Procedure. Dysphagia 1988, 2, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marten, O.; Greiner, W. EQ-5D-5L Reference Values for the German General Elderly Population. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, M.; Hutcheson, K.; Zaveri, J.; Lewin, J.; Kupferman, M.E.; Hessel, A.C.; Goepfert, R.P.; Brandon Gunn, G.; Garden, A.S.; Ferraratto, R.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes of Symptom Burden in Patients Receiving Surgical or Nonsurgical Treatment for Low-Intermediate Risk Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Comparative Analysis of a Prospective Registry. Oral Oncol. 2019, 91, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbon, C.E.A.; Yao, C.M.K.L.; Alvarez, C.P.; Goepfert, R.P.; Fuller, C.D.; Lai, S.Y.; Gross, N.D.; Hutcheson, K.A. Dysphagia Profiles after Primary Transoral Robotic Surgery or Radiation for Oropharyngeal Cancer: A Registry Analysis. Head Neck 2021, 43, 2883–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohopolski, M.J.; Diao, K.; Hutcheson, K.A.; Akhave, N.S.; Goepfert, R.P.; He, W.; Lei, X.J.; Peterson, S.K.; Shen, Y.; Sumer, B.D.; et al. Long-Term Patient-Reported Outcomes in a Population-Based Cohort Following Radiotherapy vs Surgery for Oropharyngeal Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choby, G.W.; Kim, J.; Ling, D.C.; Abberbock, S.; Mandal, R.; Kim, S.; Ferris, R.L.; Duvvuri, U. Transoral Robotic Surgery Alone for Oropharyngeal Cancer: Quality-of-Life Outcomes. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 141, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Strojan, P.; Hutcheson, K.A.; Eisbruch, A.; Beitler, J.J.; Langendijk, J.A.; Lee, A.W.M.; Corry, J.; Mendenhall, W.M.; Smee, R.; Rinaldo, A.; et al. Treatment of Late Sequelae after Radiotherapy for Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 59, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, F.Y.; Kim, H.M.; Lyden, T.H.; Haxer, M.J.; Worden, F.P.; Feng, M.; Moyer, J.S.; Prince, M.E.; Carey, T.E.; Wolf, G.T.; et al. Intensity-Modulated Chemoradiotherapy Aiming to Reduce Dysphagia in Patients With Oropharyngeal Cancer: Clinical and Functional Results. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagtap, M.; Karnad, M. Swallowing Skills and Aspiration Risk Following Treatment of Head and Neck Cancers. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 10, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langerman, A.; MacCracken, E.; Kasza, K.; Haraf, D.J.; Vokes, E.E.; Stenson, K.M. Aspiration in Chemoradiated Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007, 133, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Huang, B.S.; Hung, T.M.; Chang, Y.L.; Lin, C.Y.; Chung, C.Y.; Wu, S.C. Swallowing Ability and Its Impact on Dysphagia-Specific Health-Related QOL in Oral Cavity Cancer Patients Post-Treatment. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 36, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weymuller, E.A.; Yueh, B.; Deleyiannis, F.W.B.; Kuntz, A.L.; Alsarraf, R.; Coltrera, M.D. Quality of Life in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2000, 126, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, R.P. Studies in the Quality of Life of Head and Neck Cancer Patients: Results of a Two-Year Longitudinal Study and a Comparative Cross-Sectional Cross-Cultural Survey. Laryngoscope 2003, 113, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, U.; Zaretsky, E.; Goeze, A.; Wermter, L.; Stuck, B.A.; Birk, R.; Neff, A.; Fischer, I.; Ghanaati, S.; Sader, R.; et al. Prätherapeutische Dysphagie Bei Kopf-Hals-Tumor-Patienten. HNO 2022, 70, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, J.M.; Hildreth, A.; McColl, E.; Carding, P.N.; Hamilton, D.; Wilson, J.A. The Clinical Application of the 100 ML Water Swallow Test in Head and Neck Cancer. Oral Oncol. 2011, 47, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, L.J.; Woodman, S.H.; Ganderton, D.; Hutcheson, K.A.; Pringle, S.; Patterson, J.M. Development of the Remote 100 Ml Water Swallow Test versus Clinical Assessment in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: Do They Agree? Head Neck 2022, 44, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hey, C.; Goeze, A.; Sader, R.; Zaretsky, E. FraMaDySc: Dysphagia Screening for Patients after Surgery for Head and Neck Cancer. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2023, 280, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group Characteristics | EQ-5D-5L, MDADI n = 307 | FEES, EQ-5D-5L, MDADI n = 59 |

|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 65.88 (±9.98) | 63.20 (±9.32) |

| Female | 62 (20.33%) | 13 (22.03%) |

| Male | 245 (79.81%) | 46 (77.97%) |

| Primary tumor T size | ||

| T1 | 92 (29.97%) | 11 (18.64%) |

| T2 | 81 (26.38%) | 11 (18.64%) |

| T3 | 56 (18.24%) | 17 (28.81%) |

| T4 | 56 (18.24%) | 19 (32.20%) |

| Tx | 22 (7.21%) | 1 (1.69%) |

| Primary tumor location | ||

| Oral cavity | 24 (7.82%) | 10 (16.95%) |

| Nasopharynx | 4 (1.30%) | 0 |

| Oropharynx | 124 (40.39%) | 33 (55.93%) |

| Hypopharynx | 30 (9.77%) | 6 (10.17%) |

| Larynx | 99 (32.25%) | 9 (15.25%) |

| CUP | 22 (7.17%) | 1 (1.69%) |

| Other | 4 (1.30%) | 0 |

| Therapy | ||

| Surgery only | 74 (24.10%) | 9 (15.25%) |

| (Chemo)Radiotherapy | 113 (36.72%) | 26 (44.06%) |

| Surgery + Radiotherapy | 58 (18.89%) | 13 (22.03%) |

| Surgery + Chemoradiotherapy | 61 (19.87%) | 11 (18.64%) |

| Time after therapy | ||

| ≤5 months | 32 (10.42%) | 28 (47.46%) |

| 6–11 months | 41 (13.36%) | 12 (20.34%) |

| 1–5 years | 141 (45.93%) | 15 (25.41%) |

| >5 years | 93 (30.29%) | 4 (6.78%) |

| Feeding tube use | 47 (15.31%) | 33 (55.93%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strüder, D.; Ebert, J.; Kalle, F.; Schraven, S.P.; Eichhorst, L.; Mlynski, R.; Großmann, W. Head and Neck Cancer: A Study on the Complex Relationship between QoL and Swallowing Function. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 10336-10350. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120753

Strüder D, Ebert J, Kalle F, Schraven SP, Eichhorst L, Mlynski R, Großmann W. Head and Neck Cancer: A Study on the Complex Relationship between QoL and Swallowing Function. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(12):10336-10350. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120753

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrüder, Daniel, Johanna Ebert, Friederike Kalle, Sebastian P. Schraven, Lennart Eichhorst, Robert Mlynski, and Wilma Großmann. 2023. "Head and Neck Cancer: A Study on the Complex Relationship between QoL and Swallowing Function" Current Oncology 30, no. 12: 10336-10350. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120753

APA StyleStrüder, D., Ebert, J., Kalle, F., Schraven, S. P., Eichhorst, L., Mlynski, R., & Großmann, W. (2023). Head and Neck Cancer: A Study on the Complex Relationship between QoL and Swallowing Function. Current Oncology, 30(12), 10336-10350. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120753