Retrospective Analysis of Emotional Burden and the Need for Support of Patients and Their Informal Caregivers after Palliative Radiation Treatment for Brain Metastases

Abstract

1. Introduction

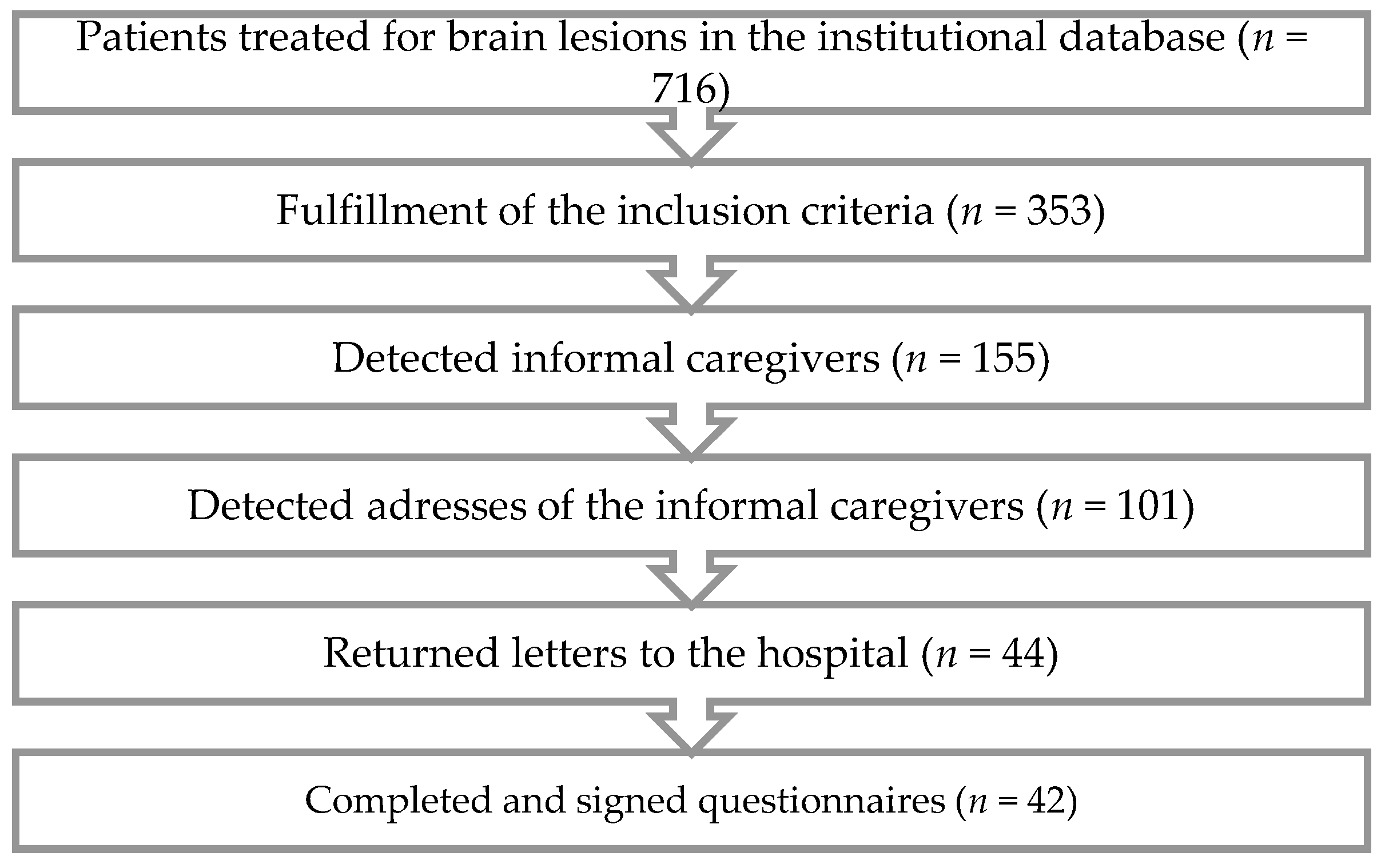

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Caregiver Characteristics

3.2. The Caregivers’ Burden and Support

3.3. The Caregivers’ Unmet Needs

3.4. Health Care Service and Information Needs

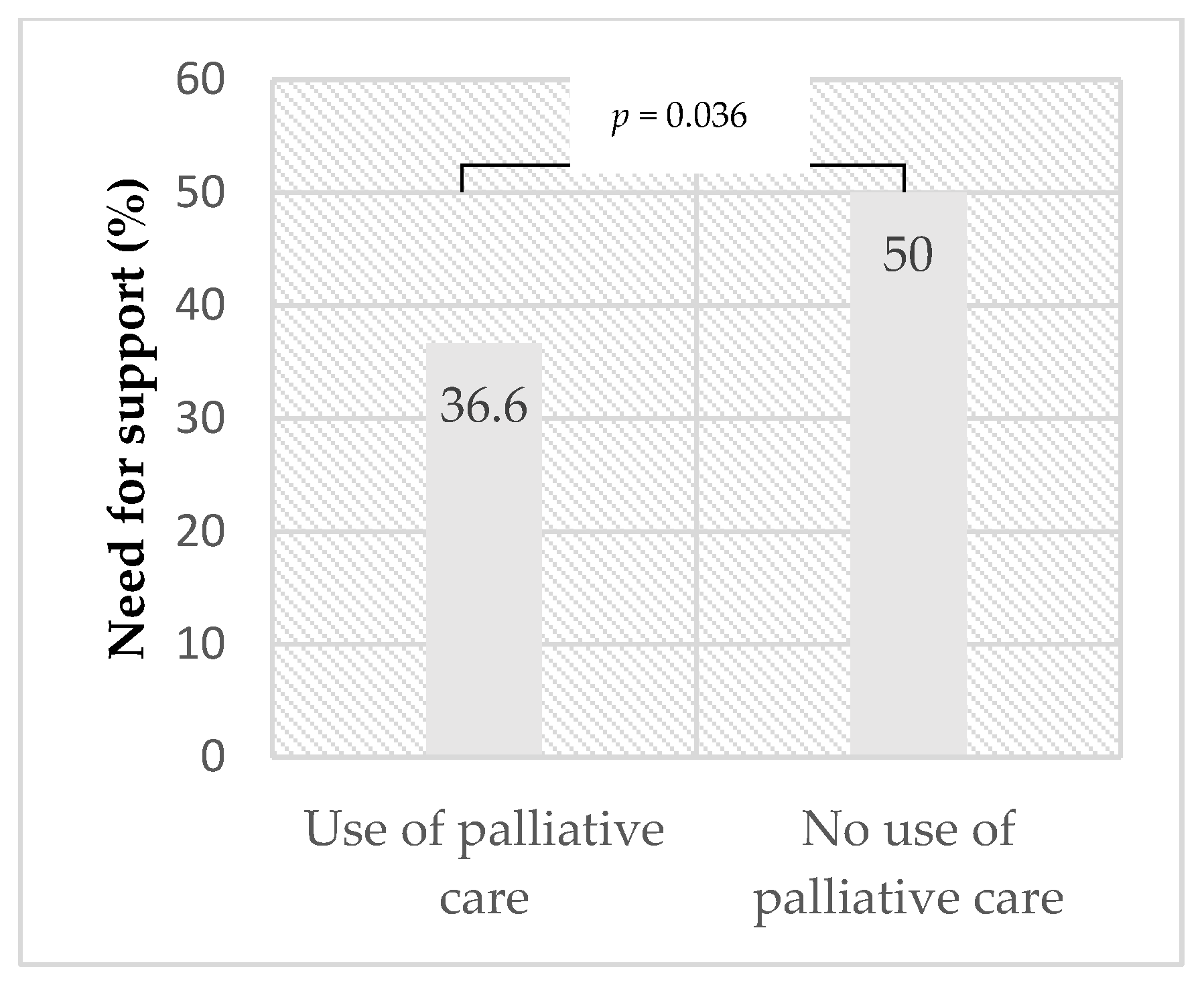

3.5. Palliative Care

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Preisler, M.; Goerling, U. Angehörige von an Krebs erkrankten Menschen. Der Onkologe 2016, 22, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitceathly, C.; Maguire, P. The psychological impact of cancer on patients’ partners and other key relatives: A review. Eur. J. Cancer 2003, 39, 1517–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketcher, D.; Otto, A.; Reblin, M. Caregivers of Patients with Brain Metastases: A Description of Caregiving Responsibilities and Psychosocial Well-being. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2020, 52, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saria, M.G.; Courchesne, N.S.; Evangelista, L.; Carter, J.L.; MacManus, D.A.; Gorman, M.K.; Nyamathi, A.M.; Phillips, L.R.; Piccioni, D.E.; Kesari, S.; et al. Anxiety and Depression Associated with Burden in Caregivers of Patients With Brain Metastases. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2017, 44, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Duhamel, F.; Dupuis, F. Guaranteed returns: Investing in conversations with families of patients with cancer. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2004, 8, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, E.; Arve, S.; Lauri, S. Informational and emotional support received by relatives before and after the cancer patient’s death. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2006, 10, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soothill, K.; Morris, S.M.; Harman, J.C.; Francis, B.; Thomas, C.; McIllmurray, M.B. Informal carers of cancer patients: What are their unmet psychosocial needs? Health Soc. Care Community 2001, 9, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertler, C.; Eisele, G.; Gramatzki, D.; Seystahl, K.; Wolpert, F.; Roth, P.; Weller, M. End-of-life care for glioma patients; the caregivers’ perspective. J. Neurooncol. 2020, 147, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Robles, P.; Fiest, K.M.; Frolkis, A.D.; Pringsheim, T.; Atta, C.; Germaine-Smith, C.S.; Day, L.; Lam, D.; Jette, N. The worldwide incidence and prevalence of primary brain tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuro Oncol. 2015, 17, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achrol, A.S.; Rennert, R.C.; Anders, C.; Soffietti, R.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Nayak, L.; Peters, S.; Arvold, N.D.; Harsh, G.R.; Steeg, P.S.; et al. Brain metastases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, B.D.; Cheung, V.J.; Patel, A.J.; Suki, D.; Rao, G. Epidemiology of metastatic brain tumors. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taphoorn, M.J.; Klein, M. Cognitive deficits in adult patients with brain tumours. Lancet Neurol. 2004, 3, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gofton, T.E.; Graber, J.; Carver, A. Identifying the palliative care needs of patients living with cerebral tumors and metastases: A retrospective analysis. J. Neurooncol. 2012, 108, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, T.; Agarwal, A.; Sium, A.; Trang, A.; Chung, C.; Papadakos, J. Informational and Supportive Care Needs of Brain Metastases Patients and Caregivers: A Systematic Review. J. Cancer Educ. 2017, 32, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwahlen, D.; Hagenbuch, N.; Carley, M.I.; Recklitis, C.J.; Buchi, S. Screening cancer patients’ families with the distress thermometer (DT): A validation study. Psychooncology 2008, 17, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krähenbühl, A.; Zwahlen, D.; Knuth, A.; Schnyder, U.; Jenewein, J.; Kuhn, C.; Büchi, S. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in cancer outpatients and their spouses. Praxis 2007, 96, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelles, W.B.; McCaffrey, R.J.; Blanchard, C.G.; Ruckdeschel, J.C. Social Supports and Breast Cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 1991, 9, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heese, O.; Vogeler, E.; Martens, T.; Schnell, O.; Tonn, J.C.; Simon, M.; Schramm, J.; Krex, D.; Schackert, G.; Reithmeier, T.; et al. End-of-life caregivers’ perception of medical and psychological support during the final weeks of glioma patients: A questionnaire-based survey. Neuro Oncol. 2013, 15, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flechl, B.; Ackerl, M.; Sax, C.; Oberndorfer, S.; Calabek, B.; Sizoo, E.; Reijneveld, J.; Crevenna, R.; Keilani, M.; Gaiger, A.; et al. The caregivers’ perspective on the end-of-life phase of glioblastoma patients. J. Neurooncol. 2013, 112, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Azuero, A.; Lyons, K.D.; Hull, J.G.; Tosteson, T.; Li, Z.; Frost, J.; Dragnev, K.H.; Akyar, I. Benefits of Early Versus Delayed Palliative Care to Informal Family Caregivers of Patients with Advanced Cancer: Outcomes From the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1446–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzner, M.A.; McMillan, S.C.; Jacobsen, P.B. Family caregiver quality of life: Differences between curative and palliative cancer treatment settings. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 1999, 17, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabe, N.; Zwahlen, D.; Büchi, S.; Moergeli, H.; Zwahlen, R.A.; Jenewein, J. Psychiatric morbidity and quality of life in wives of men with long-term head and neck cancer. Psychooncology 2008, 17, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walbert, T.; Pace, A. End-of-life care in patients with primary malignant brain tumors: Early is better. Neuro Oncol. 2016, 18, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, F.; Grassi, L.; Travado, L.; Tomamichel, M.; Gonzalez, J.R.; The SEPOS Group. Use of distress and depression thermometers to measure psychosocial morbidity among southern European cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2005, 13, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Variables | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age of death (years) | 68 | 47–85 |

| Number of organ metastases | 3.9 | 1–8 |

| ECOG performance status at start of RT | 1.4 | 0–2 |

| Disease duration (first diagnosis to death), (years) | 3.1 | 0–19 |

| n | % | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 21 | 50 |

| Male | 21 | 50 |

| Form of overall treatment (any treatment time) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 30 | 71.4 |

| Immunotherapy | 4 | 9.5 |

| Targeted Therapy | 17 | 40.5 |

| Hormone Therapy | 8 | 19 |

| Radiotherapy in total | 42 | 100 |

| WBRT | 37 | 86.1 |

| PBRT | 2 | 4.7 |

| SRS/SRT | 4 | 9.3 |

| Surgery | 17 | 40.5 |

| Entity | ||

| Lung cancer | 26 | 61.9 |

| Breast cancer | 4 | 9.5 |

| Melanoma | 4 | 9.5 |

| Urogenital cancer | 5 | 11.9 |

| Others | 3 | 7.1 |

| Number of brain metastases | ||

| 1–5 metastases | 9 | 21.4 |

| 6–10 metastases | 6 | 14.3 |

| >10 metastases | 20 | 47.6 |

| Meningeal carcinomatosis | 7 | 16.7 |

| Place of death | ||

| Home | 13 | 31 |

| Hospital | 20 | 47.6 |

| Nursing home | 8 | 19 |

| Hospice | 1 | 2.4 |

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 27 | 64.3 |

| Male | 15 | 35.7 |

| Relatives | ||

| Spouse | 34 | 81.0 |

| Daughter | 4 | 9.5 |

| Sister | 4 | 9.5 |

| Variables | n = 42 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional burden of the caregiver | 33 | 78.6 |

| Sufficient support by medical practitioners | 35 | 83.3 |

| Sufficient support by family | 37 | 88.1 |

| Health problems developed by caregiver | 10 | 23.8 |

| Involvement of palliative care | 30 | 71.4 |

| Outpatient | 16 | 38.1 |

| Inpatient | 4 | 9.5 |

| Unspecified | 10 | 23.8 |

| Psycho-oncology involved | 12 | 28.6 |

| Need for Support When | No Need | Already Supported | Low Need | Moderate Need | High Need | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receiving emotional support of the caregiver | 10 (23.8) | 8 (19.0) | 7 (16.7) | 4 (9.5) | 4 (9.5) | 9 (21.4) |

| Coping with fears about physical or mental deterioration of the patient | 7 (16.7) | 8 (19.0) | 7 (16.7) | 5 (11.9) | 9 (21.4) | 6 (14.3) |

| Handling thoughts about death or dying | 9 (21.4) | 13 (31.0) | 8 (19.0) | 1 (2.4) | 6 (14.3) | 5 (11.9) |

| Providing practical care tasks (bathing, bandage changes, administering medicine) | 16 (38.1) | 7 (16.7) | 6 (14.3) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.1) | 7 (16.7) |

| Communicating with the patient | 15 (35.7) | 4 (9.5) | 5 (11.9) | 2 (4.8) | 6 (14.3) | 10 (23.8) |

| Reducing stress of the patient | 8 (19.0) | 12 (28.6) | 5 (11.9) | 3 (7.1) | 8 (19.0) | 6 (14.3) |

| Balancing the needs of the patient vs. those of the caregiver | 12 (28.6) | 7 (16.7) | 6 (14.3) | 5 (11.9) | 3 (7.1) | 9 (21.4) |

| Looking after the caregiver’s health (eating, sleeping) | 14 (33.3) | 10 (23.8) | 5 (11.9) | 5 (11.9) | 3 (7.1) | 5 (11.9) |

| Nursing affects the caregiver’s own life | 13 (31.0) | 6 (14.3) | 5 (11.9) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.1) | 12 (28.6) |

| Need for Support When | No Need | Already Supported | Low Need | Moderate Need | High Need | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receiving opportunities to discuss the caregivers concerns with the doctors | 9 (21.4) | 8 (19.0) | 5 (11.9) | 8 (19.0) | 7 (16.7) | 5 (11.9) |

| Building confidence in doctors having discussed the patient’s case sufficiently with each other | 10 (23.8) | 7 (16.7) | 5 (11.9) | 5 (11.9) | 9 (21.4) | 6 (14.3) |

| Feeling reassured about sufficient coordination of medical services | 10 (23.8) | 7 (16.7) | 6 (14.3) | 2 (4.8) | 10 (23.8) | 7 (16.7) |

| Participating in decision making of the patient | 11 (26.2) | 9 (21.4) | 6 (14.3) | 4 (9.5) | 4 (9.5) | 8 (19.0) |

| Being involved in the medical care of the patient | 8 (19.0) | 13 (31.0) | 3 (7.1) | 4 (9.5) | 4 (9.5) | 10 (23.8) |

| Receiving information about the supportive program for the caregiver | 10 (23.8) | 8 (19.0) | 6 (14.3) | 6 (14.3) | 7 (16.7) | 5 (11.9) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lütscher, J.; Siegenthaler, C.H.; Hertler, C.; Blum, D.; Windisch, P.; Shaker, R.G.; Schröder, C.; Zwahlen, D.R. Retrospective Analysis of Emotional Burden and the Need for Support of Patients and Their Informal Caregivers after Palliative Radiation Treatment for Brain Metastases. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 4235-4244. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060338

Lütscher J, Siegenthaler CH, Hertler C, Blum D, Windisch P, Shaker RG, Schröder C, Zwahlen DR. Retrospective Analysis of Emotional Burden and the Need for Support of Patients and Their Informal Caregivers after Palliative Radiation Treatment for Brain Metastases. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(6):4235-4244. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060338

Chicago/Turabian StyleLütscher, Jamie, Christa Hauswirth Siegenthaler, Caroline Hertler, David Blum, Paul Windisch, Renate Grathwohl Shaker, Christina Schröder, and Daniel Rudolf Zwahlen. 2022. "Retrospective Analysis of Emotional Burden and the Need for Support of Patients and Their Informal Caregivers after Palliative Radiation Treatment for Brain Metastases" Current Oncology 29, no. 6: 4235-4244. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060338

APA StyleLütscher, J., Siegenthaler, C. H., Hertler, C., Blum, D., Windisch, P., Shaker, R. G., Schröder, C., & Zwahlen, D. R. (2022). Retrospective Analysis of Emotional Burden and the Need for Support of Patients and Their Informal Caregivers after Palliative Radiation Treatment for Brain Metastases. Current Oncology, 29(6), 4235-4244. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060338