Engaging Patients in Smoking Cessation Treatment within the Lung Cancer Screening Setting: Lessons Learned from an NCI SCALE Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Predictors of Enrollment and Retention in Smoking Cessation Trials in the Lung Screening Setting

1.2. Predictors of Intervention Engagement in Smoking Cessation Trials

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Univariate Predictors of Engagement in the Intensive Arm

3.2. Univariate Predictors of Engagement in the Minimal Arm

3.3. Regression Models Predicting Engagement in the Intensive Arm

3.4. Regression Models Predicting Engagement in the Minimal Arm

3.5. Intervention Feedback Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

What Is Next in the Implementation of Cessation Interventions at the Time of Lung Screening?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meza, R.; Cao, P.; Jeon, J.; Taylor, K.L.; Mandelblatt, J.S.; Feuer, E.J.; Lowy, D.R. Impact of Joint Lung Cancer Screening and Cessation Interventions Under the New Recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, D.B.; Orleans, C.T.; Niaura, R.S.; Goldstein, M.G.; Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W. Integrating Individual and Public Health Perspectives for Treatment of Tobacco Dependence under Managed Health Care: A Combined Stepped-Care and Matching Model. Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 1996, 18, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, K.; Chassagnon, G.; Frauenfelder, T.; Revel, M.-P. Ongoing Challenges in Implementation of Lung Cancer Screening. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 2347–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Aalst, C.M.; de Koning, H.J.; van den Bergh, K.A.M.; Willemsen, M.C.; van Klaveren, R.J. The Effectiveness of a Computer-Tailored Smoking Cessation Intervention for Participants in Lung Cancer Screening: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lung Cancer Amst. Neth. 2012, 76, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, A.; Taghizadeh, N.; Huang, J.; Kasowski, D.; MacEachern, P.; Burrowes, P.; Graham, A.J.; Dickinson, J.A.; Lam, S.C.; Yang, H.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Study of Integrated Smoking Cessation in a Lung Cancer Screening Program. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, U.S.; Rabe, B.; Brady, B.R.; Bell, M.L. Predictors of Client Retention in a State-Based Tobacco Quitline. J. Smok. Cessat. 2020, 15, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyestone, E.; Williams, R.M.; Luta, G.; Kim, E.; Toll, B.A.; Rojewski, A.; Neil, J.; Cinciripini, P.M.; Cordon, M.; Foley, K.; et al. Predictors of Enrollment of Older Smokers in Six Smoking Cessation Trials in the Lung Cancer Screening Setting: The Smoking Cessation at Lung Examination (SCALE) Collaboration. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021, 23, 2037–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.L.; Deros, D.E.; Fallon, S.; Stephens, J.; Kim, E.; Lobo, T.; Davis, K.M.; Luta, G.; Jayasekera, J.; Meza, R.; et al. Study Protocol for a Telephone-Based Smoking Cessation Randomized Controlled Trial in the Lung Cancer Screening Setting: The Lung Screening, Tobacco, and Health Trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2019, 82, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, J.M.; Marotta, C.; Gonzalez, I.; Chang, Y.; Levy, D.E.; Wint, A.; Harris, K.; Hawari, S.; Noonan, E.; Styklunas, G.; et al. Integrating Tobacco Treatment into Lung Cancer Screening Practices: Study Protocol for the Screen ASSIST Randomized Clinical Trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2021, 111, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, J.M.; Chang, Y.; Goshe, B.; Rigotti, N.; Gonzalez, I.; Hawari, S.; Ballini, L.; Haas, J.S.; Marotta, C.; Wint, A.; et al. A Web-Based Intervention to Increase Smokers’ Intentions to Participate in a Cessation Study Offered at the Point of Lung Screening: Factorial Randomized Trial. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e28952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.S.; Rothman, A.J.; Vock, D.M.; Lindgren, B.; Almirall, D.; Begnaud, A.; Melzer, A.; Schertz, K.; Glaeser, S.; Hammett, P.; et al. Program for Lung Cancer Screening and Tobacco Cessation: Study Protocol of a Sequential, Multiple Assignment, Randomized Trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2017, 60, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, K.L.; Miller, D.P.; Weaver, K.; Sutfin, E.L.; Petty, W.J.; Bellinger, C.; Spangler, J.; Stone, R.J.; Lawler, D.; Davis, W.; et al. The OaSiS Trial: A Hybrid Type II, National Cluster Randomized Trial to Implement Smoking Cessation during CT Screening for Lung Cancer. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2020, 91, 105963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Williams, R.M.; Eyestone, E.; Cordon, M.; Smith, L.; Davis, K.; Luta, G.; Anderson, E.D.; McKee, B.; Batlle, J.; et al. Predictors of Attrition in a Smoking Cessation Trial Conducted in the Lung Cancer Screening Setting. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2021, 106, 106429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, K.L.; Hagerman, C.J.; Luta, G.; Bellini, P.G.; Stanton, C.; Abrams, D.B.; Kramer, J.A.; Anderson, E.; Regis, S.; McKee, A.; et al. Preliminary Evaluation of a Telephone-Based Smoking Cessation Intervention in the Lung Cancer Screening Setting: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Lung Cancer 2017, 108, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferketich, A.K.; Otterson, G.A.; King, M.; Hall, N.; Browning, K.K.; Wewers, M.E. A Pilot Test of a Combined Tobacco Dependence Treatment and Lung Cancer Screening Program. Lung Cancer Amst. Neth. 2012, 76, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, M.M.; Cox, L.S.; Jett, J.R.; Patten, C.A.; Schroeder, D.R.; Nirelli, L.M.; Vickers, K.; Hurt, R.D.; Swensen, S.J. Effectiveness of Smoking Cessation Self-Help Materials in a Lung Cancer Screening Population. Lung Cancer Amst. Neth. 2004, 44, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, H.M.; Courtney, D.A.; Passmore, L.H.; McCaul, E.M.; Yang, I.A.; Bowman, R.V.; Fong, K.M. Brief Tailored Smoking Cessation Counseling in a Lung Cancer Screening Population Is Feasible: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial: Table 1. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016, 18, 1665–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadir, A.; Iliaz, S.; Yurt, S.; Ortakoylu, M.G.; Bakan, N.D.; Yazar, E. Factors Affecting Dropout in the Smoking Cessation Outpatient Clinic. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2016, 13, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hays, J.T.; Leischow, S.J.; Lawrence, D.; Lee, T.C. Adherence to Treatment for Tobacco Dependence: Association with Smoking Abstinence and Predictors of Adherence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010, 12, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupertino, A.P.; Mahnken, J.D.; Richter, K.; Cox, L.S.; Casey, G.; Resnicow, K.; Ellerbeck, E.F. Long-Term Engagement in Smoking Cessation Counseling among Rural Smokers. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2007, 18, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, N.D.; Aktürk, Ü.A. What Factors Influence Non-Adherence to the Smoking Cessation Program? Turk. Thorac. J. 2019, 20, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hestbech, M.S.; Siersma, V.; Dirksen, A.; Pedersen, J.H.; Brodersen, J. Participation Bias in a Randomised Trial of Screening for Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer 2011, 73, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnix, J.A.; Karam-Hage, M.; Blalock, J.A.; Cinciripini, P.M. The Importance of Incorporating Smoking Cessation into Lung Cancer Screening. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2018, 7, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, J.H.; Tønnesen, P.; Ashraf, H. Smoking Cessation and Lung Cancer Screening. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; p. 428. ISBN 978-1-57230-563-2. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, K.M.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care Settings. Opportunities and Limitations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 20, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.C.; Jaen, C.; Baker, T.B.; Bailey, W.; Benowitz, N.; Curry, S. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update; Clinical Practice Guideline; US Department of Health and Human Services: Rockville, MD, USA, 2008.

- Stead, L.F.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Perera, R.; Lancaster, T. Telephone Counselling for Smoking Cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 12, CD002850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poghosyan, H.; Kennedy Sheldon, L.; Cooley, M.E. The Impact of Computed Tomography Screening for Lung Cancer on Smoking Behaviors: A Teachable Moment? Cancer Nurs. 2012, 35, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.L.; Cox, L.S.; Zincke, N.; Mehta, L.; McGuire, C.; Gelmann, E. Lung Cancer Screening as a Teachable Moment for Smoking Cessation. Lung Cancer Amst. Neth. 2007, 56, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, B.; Simmons, V.N.; Palmer, A.M.; Correa, J.B.; Brandon, T.H. Smoking Cessation Interventions within the Context of Low-Dose Computed Tomography Lung Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review. Lung Cancer 2016, 98, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, C.M.; Emmons, K.M.; Lipkus, I.M. Understanding the Potential of Teachable Moments: The Case of Smoking Cessation. Health Educ. Res. 2003, 18, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.L.; Williams, R.M.; Li, T.; Luta, G.; Smith, L.; Davis, K.M.; Stanton, C.; Niaura, R.; Abrams, D.; Lobo, T.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Telephone-Based Tobacco Treatment in the Lung Cancer Screening Setting: The Georgetown Lung Screening, Tobacco, and Health Trial. Under Review.

- Biener, L.; Abrams, D.B. The Contemplation Ladder: Validation of a Measure of Readiness to Consider Smoking Cessation. Health Psychol. 1991, 10, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, E.J.; Rayens, M.K.; Hopenhayn, C.; Christian, W.J. Perceived Risk and Interest in Screening for Lung Cancer among Current and Former Smokers. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Brand, F.A.; Nagelhout, G.E.; Reda, A.A.; Winkens, B.; Evers, S.M.A.A.; Kotz, D.; van Schayck, O.C. Healthcare Financing Systems for Increasing the Use of Tobacco Dependence Treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD004305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, K.M.; Fix, B.; Celestino, P.; Carlin-Menter, S.; O’Connor, R.; Hyland, A. Reach, Efficacy, and Cost-Effectiveness of Free Nicotine Medication Giveaway Programs. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2006, 12, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinkelman, D.; Wilson, S.M.; Willett, J.; Sweeney, C.T. Offering Free NRT through a Tobacco Quitline: Impact on Utilisation and Quit Rates. Tob. Control 2007, 16, i42–i46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plain Language. Available online: https://www.nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office-communications-public-liaison/clear-communication/plain-language (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Kee, D.; Wisnivesky, J.; Kale, M.S. Lung Cancer Screening Uptake: Analysis of BRFSS 2018. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, R.; Jeon, J.; Jimenez-Mendoza, E.; Mok, Y.; Cao, P.; Foley, K.L.; Chiles, C.; Ostroff, J.; Cinciripini, P.M.; Minnix, J.; et al. NCI Smoking Cessation at Lung Examination (SCALE) Trials Brief Report: Baseline Characteristics and Comparison with the US General Population of Lung Cancer Screening Eligible Patients. Under Review.

- Park, E.R.; Chiles, C.; Cinciripini, P.M.; Foley, K.L.; Fucito, L.M.; Haas, J.S.; Joseph, A.M.; Ostroff, J.S.; Rigotti, N.A.; Shelley, D.R.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Telehealth Research in Cancer Prevention and Care: A Call to Sustain Telehealth Advances. Cancer 2021, 127, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, R.; Jeon, J.; Toumazis, I.; ten Haaf, K.; Cao, P.; Bastani, M.; Han, S.S.; Blom, E.F.; Jonas, D.E.; Feuer, E.J.; et al. Evaluation of the Benefits and Harms of Lung Cancer Screening With Low-Dose Computed Tomography: Modeling Study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2021, 325, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

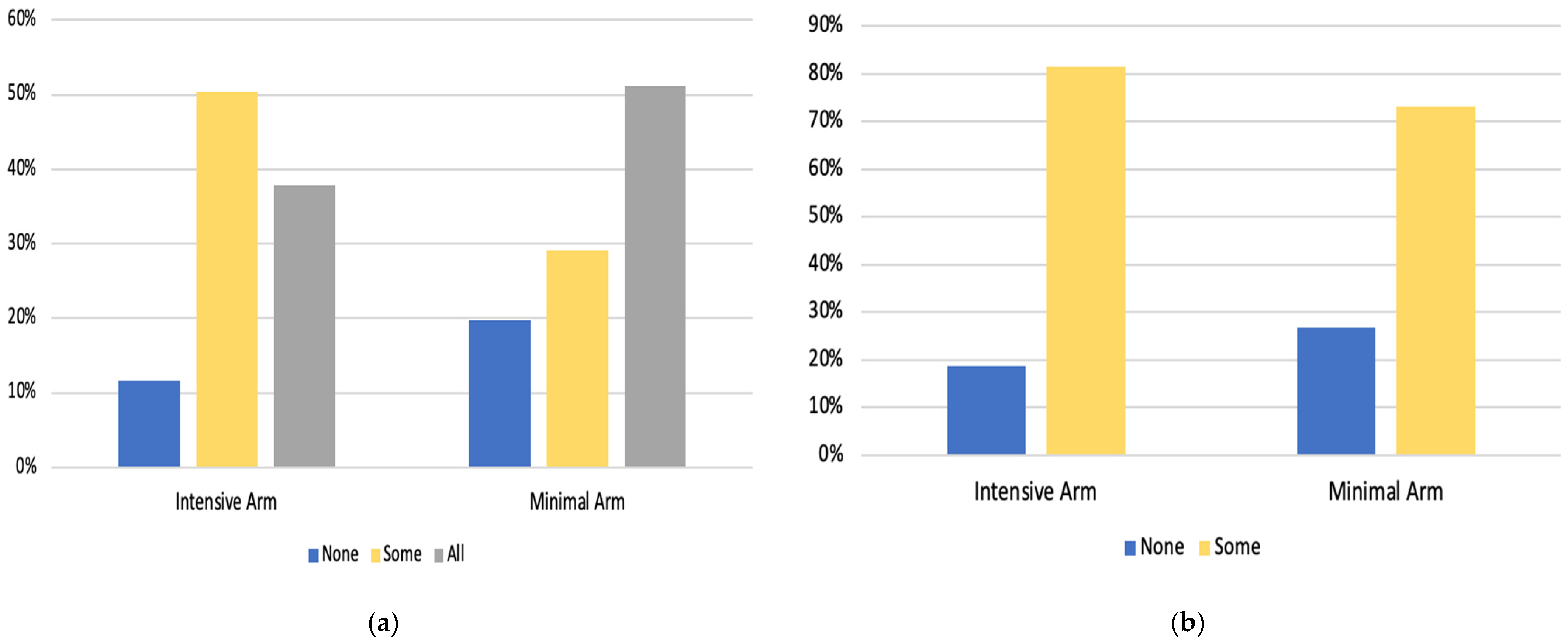

| Counseling Engagement | ||||||

| Intensive Arm (n = 409) | Minimal Arm (n = 409) | |||||

| No Engagement (0 Sessions) n = 48 (11.7%) | Some Engagement (1–7 Sessions) n = 206 (50.4%) | Complete Engagement (8 Sessions) n = 155 (37.9%) | No Engagement (0 Sessions) n = 81 (19.8%) | Some Engagement (1–2 Sessions) n = 119 (29.1%) | Complete Engagement (3 Sessions) n = 209 (51.1%) | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, n (%) | ||||||

| 50–63 Years | 25 (11.8) | 115 (54.2) | 72 (34.0) | 51 (23.7) | 66 (30.7) | 98 (45.6) *** |

| 64–80 Years | 23 (11.7) | 91 (46.2) | 83 (42.1) | 30 (15.5) | 53 (27.3) | 111 (57.2) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 21 (10.7) | 89 (45.2) | 87 (44.2) *** | 35 (18.3) | 52 (27.2) | 104 (54.5) |

| Female | 27 (12.7) | 117 (55.2) | 68 (32.1) | 46 (21.1) | 6 (30.7) | 105 (48.2) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 41 (11.3) | 179 (49.2) | 144 (39.6) * | 70 (19.2) | 110 (30.1) | 185 (50.7) |

| Black | 6 (17.6) | 20 (58.8) | 8 (23.5) | 7 (22.6) | 7 (22.6) | 17 (54.8) |

| Marital Status, n (%) | ||||||

| Married or in Marriage-like Relationship | 24 (11.6) | 100 (48.3) | 83 (40.1) | 35 (17.7) | 70 (35.4) | 93 (47.0) *** |

| Not Married | 24 (11.9) | 105 (52.2) | 72 (35.8) | 45 (21.5) | 4 (23.4) | 115 (55.0) |

| Education Level, n (%) | ||||||

| High School/GED or Less | 24 (16.8) | 65 (45.5) | 54 (37.8) ** | 38 (26.6) | 37 (25.9) | 68 (47.6) *** |

| Some College or Greater | 24 (9.1) | 140 (53.0) | 100 (37.9) | 42 (16.0) | 82 (31.2) | 139 (52.9) |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||||

| Lung Cancer Screening Result, n (%) | ||||||

| Lung-RADS 1/2 | 45 (122) | 187 (50.5) | 138 (37.3) | 72 (19.7) | 108 (29.65) | 186 (50.8) |

| Lung-RADS 3/4 | 3 (7.7) | 19 (48.7) | 17 (43.6) | 9 (20.9) | 11 (25.6) | 23 (53.5) |

| LDCT Screening, n (%) | ||||||

| Baseline scan | 29 (16.5) | 85 (48.3) | 62 (35.2) *** | 40 (23.7) | 43 (25.4) | 86 (50.9) * |

| Annual Scan | 19 (8.2) | 121 (51.9) | 93 (39.9) | 41 (17.1) | 76 (31.7) | 123 (51.3) |

| Tobacco-Related Characteristics | ||||||

| Pack Years, n (%) | ||||||

| 20–39 | 13 (11.2) | 62 (53.4) | 41 (35.3) | 26 (21.7) | 38 (31.7) | 56 (46.7) |

| 40–49 | 21 (13.5) | 75 (48.4) | 59 (38.1) | 33 (21.2) | 47 (30.1) | 76 (48.7) |

| 50+ | 14 (10.1) | 69 (50.0) | 55 (39.9) | 22 (16.8) | 33 (25.2) | 76 (58.0) |

| Cigarettes per day, n (%) | ||||||

| Less than 20 | 26 (11.7) | 109 (49.1) | 87 (39.2) | 46 (21.5) | 57 (26.6) | 111 (51.9) |

| 20 or more | 21 (11.4) | 95 (51.6) | 68 (37.0) | 35 (18.0) | 62 (32.0) | 97 (50.0) |

| Time to First Cigarette, n (%) | ||||||

| Within 5 min | 17 (14.2) | 55 (45.8) | 48 (40.0) | 30 (23.8) | 34 (27.0) | 62 (49.2) *** |

| 6 to 30 min | 14 (8.4) | 87 (52.4) | 65 (39.2) | 35 (20.6) | 46 (27.1) | 89 (52.4) |

| 31 to 60 min | 8 (11.1) | 37 (51.4) | 27 (37.5) | 5 (9.3) | 26 (48.1) | 23 (42.6) |

| After 60 min | 7 (15.2) | 25 (54.3) | 14 (30.4) | 10 (18.2) | 12 (21.8) | 33 (60.0) |

| Readiness to Quit, n (%) | ||||||

| Not considering quitting | 20 (15.3) | 66 (50.4) | 45 (34.4) | 25 (19.1) | 38 (29) | 68 (51.9) |

| Next 6 months | 8 (10.3) | 42 (53.8) | 28 (35.9) | 22 (26.8) | 26 (31.7) | 34 (41.5) |

| Next 30 days | 20 (10) | 98 (49) | 82 (41) | 34 (17.3) | 55 (28.1) | 107 (54.6) |

| Motivation to Quit, Mean (SD), Median (1 = low motivation, 10 = high motivation) | 6.30 (2.5), 6.00 | 6.83 (2.3), 7.00 | 6.76 (2.3), 7.00 | 6.38 (2.4), 6.00 | 6.64 (2.0), 7.00 | 6.77 (2.3), 7.00 |

| Confidence in Quitting, Mean (SD), Median (1 = low confidence, 10 = high confidence) | 5.66 (2.7), 6.00 | 5.81 (2.4), 5.00 | 6.03 (2.5), 6.00 | 5.62 (2.5), 5.00 | 5.53 (2.7), 5.00 | 6.05 (2.6), 6.00 * |

| Psychological Variables | ||||||

| Comparative Risk, n (%) | ||||||

| Lower risk | 7 (11.1) | 29 (46.0) | 27 (42.9) | 18 (29.0) | 19 (30.6) | 25 (40.3) * |

| About the same | 18 (10.8) | 82 (49.4) | 66 (39.8) | 33 (20.8) | 41 (25.8) | 85 (53.5) |

| Higher risk | 18 (11.0) | 88 (54.0) | 57 (35.0) | 25 (15.3) | 52 (31.9) | 86 (52.8) |

| Worry about Lung Cancer, n (%) | ||||||

| No/Little Worry | 11 (11.7) | 50 (53.2) | 33 (35.1) | 16 (17.8) | 28 (31.1) | 46 (51.1) |

| Somewhat | 20 (12.3) | 78 (47.9) | 65 (39.9) | 26 (16.1) | 51 (31.7) | 84 (52.2) |

| Extremely | 16 (10.8) | 77 (52.0) | 55 (37.2) | 36 (24.2) | 39 (26.2) | 74 (49.7) |

| (b) | ||||||

| Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) Engagement | ||||||

| Intensive Arm | Minimal Arm | |||||

| (n = 409) | (n = 409) | |||||

| No NRT n = 76 (18.6%) | Some NRT (1–4 Boxes) n = 333 (81.4%) | No NRT n = 110 (26.9%) | Some NRT (1 Box) n = 299 (73.1%) | |||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, n (%) | ||||||

| 50–63 Years | 39 (18.4) | 173 (81.6) | 61 (28.4) | 154 (71.6) | ||

| 64–80 Years | 37 (18.8) | 160 (81.2) | 49 (25.3) | 145 (74.7) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 33 (16.8) | 164 (83.2) | 47 (24.6) | 144 (75.4) | ||

| Female | 43 (20.3) | 169 (79.7) | 63 (28.9) | 155 (71.1) | ||

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 67 (18.4) | 297 (81.6) | 97 (26.6) | 268 (73.4) | ||

| Black | 6 (17.6) | 28 (82.4) | 9 (29.0) | 22 (71.0) | ||

| Marital Status, n (%) | ||||||

| Married or in Marriage-like Relationship | 39 (18.8) | 168 (81.2) | 51 (25.8) | 147 (74.2) | ||

| Not Married | 37 (18.4) | 164 (81.6) | 58 (27.8) | 151 (72.2) | ||

| Education Level, n (%) | ||||||

| High School/GED or Less | 32 (22.4) | 111 (77.6) * | 42 (29.4) | 101 (70.6) | ||

| Some College or Greater | 44 (16.7) | 220 (83.3) | 67 (25.5) | 196 (74.5) | ||

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||||

| Lung Cancer Screening Result, n (%) | ||||||

| Lung-RADS 1/2 | 71 (19.2) | 299 (80.8) | 98 (26.8) | 268 (73.2) | ||

| Lung-RADS 3/4 | 5 (12.8) | 34 (87.2) | 12 (27.9) | 31 (72.1) | ||

| LDCT Screening, n (%) | ||||||

| Baseline scan | 36 (20.5) | 140 (79.5) | 48 (28.4) | 121 (71.6) | ||

| Annual Scan | 40 (17.2) | 193 (82.8) | 62 (25.8) | 178 (74.2) | ||

| Tobacco-Related Characteristics | ||||||

| Pack Years, n (%) | ||||||

| 20–39 | 19 (16.4) | 97 (83.6) | 41 (34.2) | 79 (65.8) ** | ||

| 40–49 | 34 (21.9) | 121 (78.1) | 40 (25.6) | 116 (74.4) | ||

| 50+ | 23 (16.7) | 115 (83.3) | 29 (22.1) | 102 (77.9) | ||

| Cigarettes per day, n (%) | ||||||

| Less than 20 | 42 (18.9) | 180 (81.1) | 65 (30.4) | 149 (69.6) * | ||

| 20 or more | 33 (17.9) | 151 (82.1) | 45 (23.2) | 149 (76.8) | ||

| Time to First Cigarette, n (%) | ||||||

| Within 5 min | 25 (20.8) | 95 (79.2) ** | 35 (27.8) | 91 (72.2) | ||

| 6 to 30 min | 22 (13.3) | 144 (86.7) | 45 (26.5) | 125 (73.5) | ||

| 31 to 60 min | 13 (18.1) | 59 (81.9) | 10 (18.5) | 44 (81.5) | ||

| After 60 min | 13 (28.3) | 33 (71.7) | 17 (30.9) | 38 (69.1) | ||

| Readiness to Quit, n (%) | ||||||

| Not considering quitting | 30 (22.9) | 101 (77.1) | 37 (28.2) | 94 (71.8) | ||

| Next 6 months | 12 (15.4) | 66 (84.6) | 24 (29.3) | 58 (70.7) | ||

| Next 30 days | 34 (17.0) | 166 (83.0) | 49 (25.0) | 147 (75.0) | ||

| Motivation to Quit, Mean (SD), Median (1 = low motivation, 10 = high motivation) | 6.38 (2.5), 6.00 | 6.82 (2.3), 7.00 * | 6.47 (2.4), 6.00 | 6.73 (2.2), 7.00 | ||

| Confidence in Quitting, Mean (SD), Median (1 = low confidence, 10 = high confidence) | 5.63 (2.6), 5.00 | 5.93 (2.5), 6.00 | 5.80 (2.6), 6.00 | 5.82 (2.6), 6.00 | ||

| Psychological Variables | ||||||

| Comparative Risk, n (%) | ||||||

| Lower risk | 12 (19.0) | 51 (81.0) | 24 (38.7) | 38 (61.3) *** | ||

| About the same | 30 (18.1) | 136 (81.9) | 43 (27.0) | 116 (73.0) | ||

| Higher risk | 29 (17.8) | 134 (82.2) | 32 (19.6) | 131 (80.4) | ||

| Worry about Lung Cancer, n (%) | ||||||

| No/Little Worry | 16 (17.0) | 78 (83.0) | 26 (28.9) | 64 (71.1) | ||

| Somewhat | 33 (20.2) | 130 (79.8) | 36 (22.4) | 125 (77.6) | ||

| Extremely | 25 (16.9) | 123 (83.1) | 43 (28.9) | 106 (71.1) | ||

| (a) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensive Arm | Minimal Arm | |||

| Some Engagement | Complete Engagement | Some Engagement | Complete Engagement | |

| (1–7 Sessions) | (8 Sessions) | (1–2 Sessions) | (3 Sessions) | |

| Reference: 0 Sessions | Reference: 0 Sessions | Reference: 0 Sessions | Reference: 0 Sessions | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | n/a | n/a | ||

| 50–63 Years | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 64–80 Years | 1.5 (0.78–2.8) | 1.9 (1.1–3.4) * | ||

| Gender | n/a | n/a | ||

| Male | 0.94 (0.48–1.8) | 1.6 (0.82–3.2) | ||

| Female | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Race | n/a | n/a | ||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Black | 1.1 (0.41–3.1) | 0.56 (0.18–1.8) | ||

| Marital Status | n/a | n/a | ||

| Married or in Marriage-like Relationship | 2.0 (1.1–3.8) * | 1.1 (0.62–2.0) | ||

| Not Married | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Education Level | ||||

| High School/GED or Less | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Some College or Greater | 2.1 (1.1–4.0) * | 1.7 (0.85–3.3) | 2.1 (1.1–3.9) * | 1.9 (1.1–3.4) * |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||

| LDCT Screening | ||||

| Baseline scan | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Annual Scan | 2.1 (1.1–4.2) * | 1.9 (0.98–3.9) | 2.0 (1.04–3.8) * | 1.8 (0.99–3.2) |

| Tobacco-Related Characteristics | ||||

| Time to First Cigarette | n/a | n/a | ||

| Within 5 min | 1.2 (0.40–3.4) | 1.8 (0.68–4.6) | ||

| 6 to 30 min | 3.2 (1.03–9.9) * | 1.7 (9.57–5.3) | ||

| 31 to 60 min | 0.94(0.45–1.9) | 1.2 (0.62–2.3) | ||

| After 60 min | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Confidence in Quitting | n/a | n/a | 1.0 (0.91–1.2) | 1.1 (0.99–1.3) |

| Psychological Variables | ||||

| Comparative Risk (T1) | n/a | n/a | ||

| Lower risk | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| About the same | 1.0 (0.42–2.4) | 1.9 (0.83–4.2) | ||

| Higher risk | 1.9 (0.81–4.8) | 2.8 (1.2–6.6) * | ||

| (b) | ||||

| Intensive Arm | Minimal Arm | |||

| Some NRT (up to 8 Weeks of NRT) Reference: No NRT | Some NRT (2 Weeks of NRT) Reference: No NRT | |||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |||

| Demographics | ||||

| Education Level | n/a | |||

| High School/GED or Less | 1.0 | |||

| Some College or Greater | 1.6 (0.91–2.6) | |||

| Tobacco-Related Characteristics | ||||

| Pack Years | n/a | |||

| 20–39 | 1.0 | |||

| 40–49 | 1.5 (0.87–2.7) | |||

| 50+ | 1.9 (1.1–3.5) * | |||

| Cigarettes per day | n/a | |||

| Less than 20 | 1.0 | |||

| 20 or more | 1.2 (0.75–2.0) | |||

| Time to First Cigarette | n/a | |||

| Within 5 min | 2.0 (0.81–4.9) | |||

| 6 to 30 min | 2.8 (1.3–6.2) * | |||

| 31 to 60 min | 1.9 (0.83–4.1) | |||

| After 60 min | 1.0 | |||

| Motivation to Quit | 1.1 |(0.97–1.2) | n/a | ||

| Psychological Variables | ||||

| Comparative Risk (T1) | n/a | |||

| Lower risk | 1.0 | |||

| About the same | 1.8 (0.96–3.4) | |||

| Higher risk | 2.7 (1.4–5.2) ** | |||

| Intensive Arm (n = 312) | Minimal Arm (n = 306) | Total (n = 618) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counseling Feedback | ||||

| Did you receive smoking cessation support from our project? | ||||

| No | 14 (4.5) | 31 (10.2) | 45 (7.3) | |

| Yes | 297 (95.5) | 273 (89.8) | 570 (92.7) | 0.007 |

| Refused | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| How satisfied were you with the counseling sessions that were conducted over the phone? (n = 570) | ||||

| Not at all | 2 (0.7) | 8 (2.9) | 10 (1.8) | |

| A little satisfied | 10 (3.4) | 15 (5.5) | 25 (4.4) | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 35 (11.9) | 64 (23.4) | 99 (17.5) | |

| Very satisfied | 247 (84) | 186 (68.1) | 433 (76.4) | <0.001 |

| Refused | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| How much did the telephone counseling provided by this project help you to become more ready to quit smoking? | ||||

| Not at all | 5 (1.7) | 16 (6) | 21 (3.8) | |

| A little | 15 (5.1) | 25 (9.4) | 40 (7.1) | |

| Somewhat | 67 (22.8) | 82 (30.8) | 149 (26.6) | |

| Very Much | 207 (70.4) | 143 (53.8) | 350 (62.5) | <0.001 |

| Refused | 3 | 5 | 8 | |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Would you have preferred more counseling calls, fewer calls, or it was the right number of calls? | ||||

| Preferred Fewer Calls | 15 (5.2) | 7 (2.7) | 22 (4.0) | |

| It was the right amount of calls | 208 (71.5) | 156 (59.8) | 364 (65.9) | |

| Preferred more calls | 68 (23.4) | 98 (37.5) | 166 (30.1) | 0.001 |

| Refused | 6 | 9 | 15 | |

| Missing | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| Please tell me about your preference for stop smoking counseling conducted over the phone vs. in person. | ||||

| I prefer in person | 21 (7.2) | 24 (9.1) | 45 (8.1) | |

| Neutral/no preference | 131 (45) | 120 (45.3) | 251 (45.1) | |

| I prefer telephone counseling | 139 (47.8) | 121 (45.7) | 260 (46.8) | 0.68 |

| Refused | 6 | 6 | 12 | |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Nicotine Patch Feedback (n = 618) | ||||

| Did you receive nicotine patches from our project? | ||||

| No | 38 (12.3) | 54 (17.8) | 92 (15) | |

| Yes | 272 (87.7) | 249 (82.2) | 521 (85) | 0.056 |

| Refused | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Did you receive all of the patches that you requested? (n = 521) | ||||

| No | 16 (6) | 12 (5.2) | 28 (5.6) | |

| Yes | 252 (94) | 217 (94.8) | 469 (94.4) | 0.725 |

| Refused | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Missing | 3 | 20 | 23 | |

| Did you use the nicotine patches? | ||||

| No | 50 (18.4) | 84 (33.9) | 134 (25.8) | |

| Yes | 222 (81.6) | 164 (66.1) | 386 (74.2) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| How satisfied were you with the nicotine patches that you received? | ||||

| Not at all satisfied | 15 (6.8) | 20 (12.3) | 35 (9.2) | |

| A Little satisfied | 15 (6.8) | 25 (15.4) | 40 (10.5) | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 61 (27.9) | 43 (26.5) | 104 (27.3) | |

| Very satisfied | 128 (58.4) | 74 (45.7) | 202 (53) | 0.006 |

| Refused | 8 | 7 | 15 | |

| How much did the nicotine patches provided by this project help you to become more ready to quit smoking? | ||||

| Not at all | 25 (10.1) | 42 (20.2) | 67 (14.7) | |

| A Little | 32 (12.9) | 34 (16.3) | 66 (14.5) | |

| Somewhat | 53 (21.4) | 56 (26.9) | 109 (23.9) | |

| Very Much | 138 (55.6) | 76 (36.5) | 214 (46.9) | <0.001 |

| Refused | 17 | 29 | 46 | |

| Missing | 7 | 12 | 19 | |

| Did you purchase more patches to use, in addition to the ones we sent to you? | ||||

| No | 230 (85.5) | 176 (72.4) | 406 (79.3) | |

| Yes | 39 (14.5) | 67 (27.6) | 106 (20.7) | <0.001 |

| Refused | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Williams, R.M.; Eyestone, E.; Smith, L.; Philips, J.G.; Whealan, J.; Webster, M.; Li, T.; Luta, G.; Taylor, K.L.; on behalf of the Lung Screening, Tobacco, Health Trial. Engaging Patients in Smoking Cessation Treatment within the Lung Cancer Screening Setting: Lessons Learned from an NCI SCALE Trial. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 2211-2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29040180

Williams RM, Eyestone E, Smith L, Philips JG, Whealan J, Webster M, Li T, Luta G, Taylor KL, on behalf of the Lung Screening, Tobacco, Health Trial. Engaging Patients in Smoking Cessation Treatment within the Lung Cancer Screening Setting: Lessons Learned from an NCI SCALE Trial. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(4):2211-2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29040180

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilliams, Randi M., Ellie Eyestone, Laney Smith, Joanna G. Philips, Julia Whealan, Marguerite Webster, Tengfei Li, George Luta, Kathryn L. Taylor, and on behalf of the Lung Screening, Tobacco, Health Trial. 2022. "Engaging Patients in Smoking Cessation Treatment within the Lung Cancer Screening Setting: Lessons Learned from an NCI SCALE Trial" Current Oncology 29, no. 4: 2211-2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29040180

APA StyleWilliams, R. M., Eyestone, E., Smith, L., Philips, J. G., Whealan, J., Webster, M., Li, T., Luta, G., Taylor, K. L., & on behalf of the Lung Screening, Tobacco, Health Trial. (2022). Engaging Patients in Smoking Cessation Treatment within the Lung Cancer Screening Setting: Lessons Learned from an NCI SCALE Trial. Current Oncology, 29(4), 2211-2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29040180