Models of Follow-Up Care and Secondary Prevention Measures for Survivors of Colorectal Cancer: Evidence-Based Guidelines and Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Research Questions

- Are there optimal models of follow-up care for persons who have completed treatment for CRC (i.e., which healthcare professionals should conduct patient follow-up?)

- What are the signs and/or symptoms that may signify a potential recurrence of CRC and therefore warrant more investigation?

- What are patients’ post-treatment informational and support needs regarding their risk of recurrence and common long-term and late effects of CRC?

2. Materials and Methods

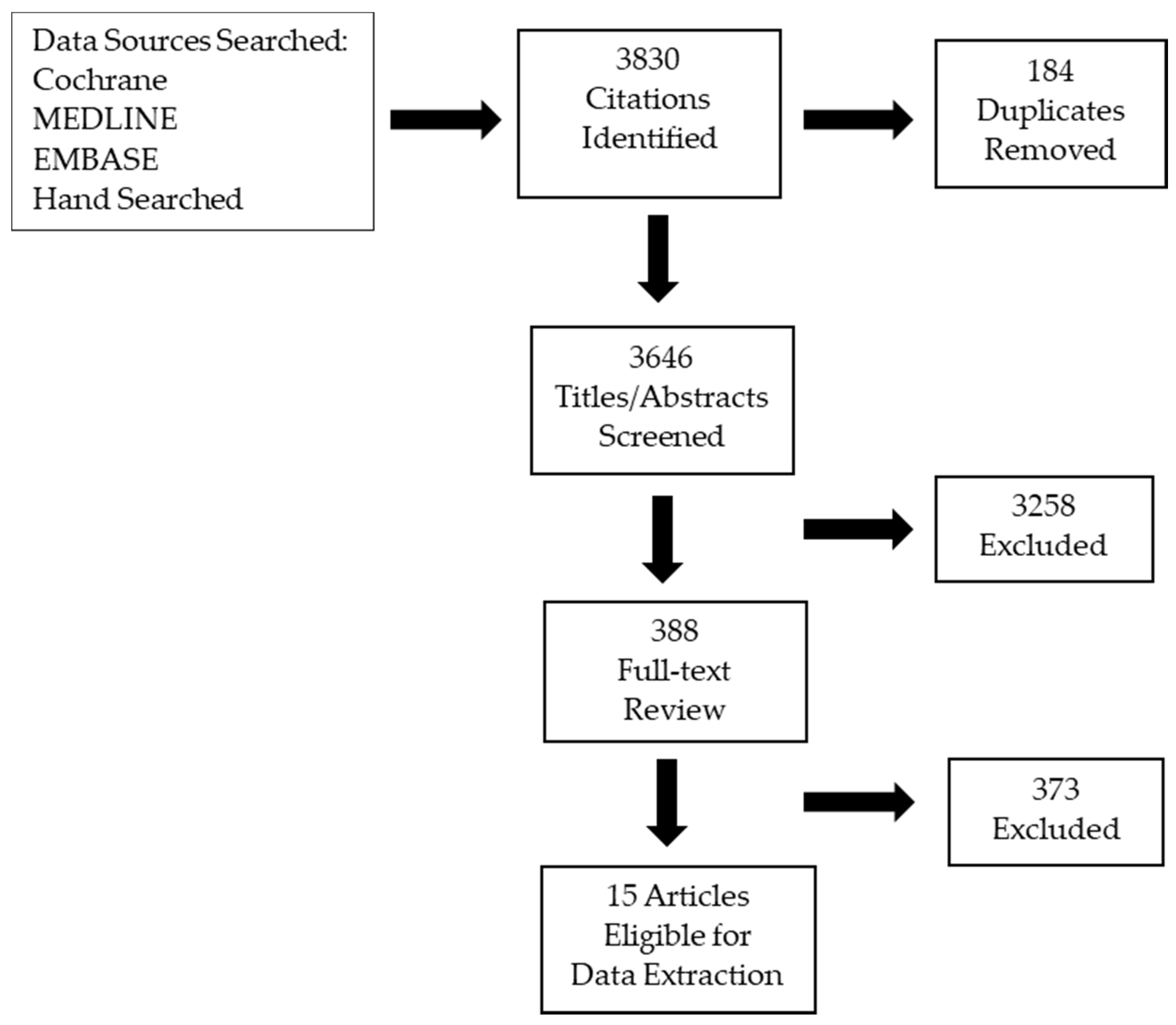

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Internal and External Review

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search Results

3.2. Internal and External Review

4. Recommendations, Key Evidence and Interpretation of the Evidence

- Follow-up care is complex and requires multidisciplinary, coordinated care of the patient delivered by the cancer specialist, family physician or nurse practitioner, and allied health professionals.

- The roles and responsibilities of the multidisciplinary team members need to be clearly defined and the patient needs to know when and how to contact each member of the team.

- Evidence: Preferred models of follow-up care

- The signs and symptoms of recurrence may be subtle or asymptomatic and must be considered in the context of the patient’s overall health and pre-existing conditions. There is insufficient evidence to recommend any individual sign or symptom or combination of signs and symptoms as a strong predictor of recurrence.

- Patients should be educated about the potential signs and symptoms of CRC recurrence (see Table 1) and know which member of the multidisciplinary care team they should contact if they develop any new or concerning signs or symptoms.

- Evidence: Signs and symptoms of potential recurrence

- Psychosocial support about the risk of CRC recurrence and provision of empathetic, effective, and coordinated communication are most highly valued by patients for post-treatment physical effects and symptom control.

- Continuing professional education should emphasize the importance of communication skills and coordination of communication between the patient and family, and healthcare providers. A list of late and long-term physical and psychosocial effects of CRC is found in Table 2 below.

- Evidence: Post-treatment informational and support needs for CRC survivors

- Clear explanation of treatments options along with potential effectiveness and adverse effects.

- The physician should ensure that patients provide the amount of detail they prefer to receive and to enable the patients’ desired amount of involvement in decision making.

- Clinicians need to ensure that the patient understands the information, and their reactions in order to provide emotional support.

- Clinicians need to provide written materials and should consider offering audio recordings of key consultations. The use of a specialist nurse or counsellor, a follow-up letter, and/or educational programs may also assist in recall of information.

- Information should be made available over time and longer appointments that review information that allows for further integration could be scheduled.

- Families and caregivers of patients should be kept informed of discussions and information.

- Evidence: Long-term and late treatment effects

5. Discussion

Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Literature Search Strategy

- MEDLINE

- exp colorectal neoplasms/

- colorectal cancer:.mp.

- rectal cancer:.mp.

- CRC:.mp.

- or/1–4 6. surveillance:.mp.

- follow-up:.mp.

- survivor:.mp.

- prevent:.mp.

- (late adj2 effect:).mp.

- or/6–10

- 5 and 11

- recurrence/

- neoplasm recurrence, local/

- 15. recurren:.mp.

- or/13–15

- 12 and 16

- limit 17 to (english language and humans) 19. limit 18 to yr = “2011–current”

- meta-analysis.pt.

- meta-analy$.tw.

- metaanal$.tw.

- (systematic adj (review$1 or overview$1)).tw.

- meta-analysis as topic/

- or/20–24

- cochrane.ab.

- (cinahl or cinhal).ab.

- embase.ab.

- scientific citation index.ab.

- bids.ab.

- cancerlit.ab.

- or/26–31 33. reference list$.ab.

- bibliograph$.ab.

- hand-search$.ab.

- relevant journals.ab.

- manual search$.ab.

- or/33–37 39. selection criteria.ab.

- data extraction.ab.

- 39 or 40 42. review.pt.

- review literature as topic/

- 42 or 43

- 41 and 44

- comment.pt.

- letter.pt.

- editorial.pt.

- or/46–48

- 25 or 32 or 38 or 45

- 50 not 49

- practice guideline/53. practice guideline$.mp.

- 52 or 53

- 51 or 54

- 19 and 55

- 19 not 49

- (comment or letter or editorial or note or erratum or short survey or news or newspaper article or patient education handout or case reports or historical article).pt.

- 19 not 58

- 59 and 55

- 59 not 55 62. case series.mp.

- 61 not 62

- 59 not 62

- EMBASE

- exp colorectal cancer/or exp colorectal carcinoma/or exp colorectal tumor/or exp colorectal tumour/

- colorectal cancer:.mp.

- rectal cancer:.mp.

- CRC:.mp.

- or/1–4

- surveillance:.mp.

- exp follow-up/

- after care/

- long term care/

- follow-up:.mp.

- survivor:.mp.

- prevent:.mp.

- (late adj2 effect:).mp.

- or/6–13

- 5 and 14

- exp recurrent cancer/or exp recurrent disease/

- recurren:.mp.

- 16 or 17

- 15 and 18

- limit 19 to (human and english language)

- limit 20 to yr = “2011–current”

- exp meta-analysis/

- ((meta adj analy$) or metaanaly$).tw.

- (systematic adj (review$1 or overview$1)).tw.

- or/22–24

- cancerlit.ab.

- cochrane.ab.

- embase.ab.

- (cinahl or cinhal).ab.

- scientific citation index.ab.

- bids.ab.

- or/26–31 33. reference list$.ab.

- bibliograph$.ab.

- hand-search$.ab.

- manual search$.ab.

- relevant journals.ab.

- or/33–37

- data extraction.ab.

- selection criteria.ab.

- 39 or 40

- review.pt.

- 41 and 42

- letter.pt.

- editorial.pt.

- 44 or 45

- 25 or 32 or 38 or 43

- 47 not 46

- exp practice guideline

- practice guideline$.tw.

- 49 or 50

- 48 or 51

- 21 and 52

Appendix B. Study Characteristics

| Study | Number of Studies | Topic | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jeffery, 2019 [2] | 19 | Overall survival | RCTs that compared different healthcare professionals and found no differences in a subgroup analysis (Χ2 = 0.40; p = 0.53; I2 = 0%) between FP or NP-led follow-up (2 studies) and hospital follow-up (13 studies). The overall effect on overall survival was similar (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.80 to 1.03, p = 0.14). |

| Berian [15] | 16 | Patients’ perceptions and expectations of routine surveillance | 5 studies showed a preference for specialist-led care; 4 studies found equivalent preference for NP- and specialist-led follow-up; 4 studies showed equivalent preference for specialist- and FP-led care 1 study showed strong preference for NP-led follow-up over specialist-led follow-up patients reported high satisfaction with follow-up and believed that continued follow-up was important for the detection of recurrence. preferences varied for a given type of provider to conduct follow-up surveillance, satisfaction was generally high regardless of provider. |

| Kotronoulas [24] | 54 studies | Supportive care needs of people living with and beyond CRC | Identified 136 individual needs were identified and classified into 8 conceptual domains that included: (i) physical and cognitive, (ii) psychosocial and emotional, (iii) family related, (iv) social, (v) interpersonal and intimacy, (vi) daily living, (vii) Information/education, and (viii) patient-physician communication |

| Study | Provider Used/Surveillance Person/Schedule | Number of Patients | Median Observation (Months) | Overall Recurrence Rate (%) | Timeliness/Compliance | Rate of Late Effects/ Metastases | Time to Recurrence | Quality of Life/Patient Satisfaction | Unannounced Follow-Ups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augestad, 2013 [16] RCT | FPs Surgeons | 55 55 | 75% for 12 mos, and 52% for 24 mos | 10.9 14.5 | Response rate of 96% for QoL questionnaire | NA | 35 days 45 days (Reported as serious clinical event) | No significant effect on QoL main outcome measures; EORTC QLQ C-30 subscales reported significant effects in favour of FP follow-up | 3 4 (Number of metastases surgeries) |

| Strand, 2011 [17] RCT Rectal cancer patients | Surgeon NP | 56 54 | 36 | 0 | All patients completed the questionnaire | 7 8 Distant metastases | NA | Overall high patient satisfaction; VAS 9.4 for surgeon and 9.5 for NP | 4 surgeries for distant metastases, 9 received palliative chemotherapy |

| Coeburgh van den Braak, 2018 [18] Prospective | NPC No NPC | 394 287 | 34.3 for DFS; 67.9 for OS | 12.5 | Involvement of an NPC resulted in a higher adherence to follow-up (84.3 vs. 73.9%, p = 0.001) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Study | Outcome | FP or NP vs. Hospital | FP vs. Surgeon | NP vs. Surgeon | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||||||

| Jeffrey [2] | No difference | |||||

| Recurrence | ||||||

| Augestad [16] | Mean time until diagnosis | No difference | ||||

| Cancer recurrence | No difference | |||||

| Died by metastatic | No difference | |||||

| Strand [17] | Metastatic cancer | No difference | ||||

| QoL | ||||||

| Augestad [16] | Overall QoL | No difference | ||||

| Role functioning | FP better p = 0.02 | |||||

| Emotional function | FP better p = 0.01 | |||||

| Pain | FP better p = 0.01 | |||||

| False positives | No difference | |||||

| Hospital travels (+cost) | FP better p < 0.001 | |||||

| Patient satisfaction | ||||||

| Strand [17] | Pt satisfaction | No difference | ||||

| Anxiety | No difference | |||||

| Sufficient time spent | No difference | |||||

| Unannounced follow-ups | ||||||

| Strand [17] | Longer consultation time | NP longer p = 0.001 | ||||

| Blood samples | NP more p = 0.003 | |||||

| Radiological tests | No difference | |||||

| Adherence | ||||||

| Augestad [16] | Healthcare contacts | FP had more | ||||

| Diagnostic tests | FP had more | |||||

| Coeburgh vander Braak [18] | Scheduled surveillance | Hospital with dedicated NPC better p = 0.001 | ||||

| Patient preference | ||||||

| Weildraaijer [19] | Pt preference | No difference | ||||

| Berian SR, n = number of articles [15] | Pt preference | Preference for specialist led: n = 5 | ||||

| Preference for NP led over specialist: n = 1 | ||||||

| Equivalent NP vs. specialist led: n = 4 | ||||||

| Equivalent specialist vs. FP led: n = 4 | ||||||

| Study | Follow-Up Program Intensity | Number of Patients and Disease Type | Median Observation (Months) | Overall Recurrence and Time to Recurrence | Rate of Late Effects/ Metastases | Signs and Symptoms Associated with Risk of Recurrence (Number and %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duineveld, 2016 [22] Retrospective cohort | CEA testing every 3 to 6 months during the first 3 years and 6 months during the following 2 years; abdominal imaging every 6 months for first 2 years and annually for following 3 years | 446 93 (21%) stage I carcinoma, 176 (39%) stage II, 176 (39%) stage III; majority carcinoma of left colon (55%) | 34 | 74 pts (16.6%) 43 (58%), detected during a scheduled follow-up visit; 41 (95%) asymptomatic 31 (42%), found during non-scheduled interval visits; 26 (84%) of these patients were symptomatic Time to recurrence: 13.7 months | 9 lung metastases | Symptoms reported during interval visits leading to detection of recurrent disease Abdominal pain: 15 (57.7) Altered defecation: 11 (42.3) Weight loss: 6 (23.1) Pain in back of pelvis: 4 (15.4) Fatigue: 2 (7.7) Dyspnea: 2 (7.7) Loss of appetite: 2 (7.7) Other (including urine retention, hematuria or cough): 3 (11.6) >1 symptom: 14 (53.8) |

| Augested, 2014 [21] RCT | CEA testing and clinical exam every 3 months during the first 2 years and 6 months during the following 3 years; chest x-ray and liver ultrasound every 6 months for first 2 years and annually for following 3 years; colonoscopy at 1 and 4 years | 110 Dukes’ stage A, B or C colon cancer | 24 | 14 pts (12.7%) 7 had symptoms 7 found during visit Time to Recurrence: 45 days in surgeon group and 35 days in the GP group (p = 0.46) | 48 serious clinical events (SCE; episode leading to suspicion of cancer recurrence) | Of 48 SCEs; 31 (65%) were initiated by emerging symptoms 17 (35%) were initiated by test findings. 14 pts had true colon cancer recurrence. 7 pts had symptoms: Abdominal pain-4 Blood in stool-1 Weight loss-1 Stoma bleeding-1 7 pts had radiologically detected lesions (n = 4) and elevated CEA levels (n = 3) |

Appendix C. Quality Assessment Scores

| Guideline | Domain 1: Scope and Purpose | Domain 2: Stakeholder Involvement | Domain 3: Rigor of Development | Domain 4: Clarity of Presentation | Domain 5: Applicability | Domain 6: Editorial Independence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OH (CCO) [8] | 100% | 58.3% | 75% | 83.3% | 18.7% | 83.3% |

| ESC [19] | 95.2% | 42.8% | 78.5% | 85.7% | 28.5% | 78.5% |

| NCCN-colon [14] | 75% | 61.1% | 67.7% | 69.4% | 66.7% | 83.3% |

| CCA [13] | 95.2% | 90.4% | 85.7% | 71.4% | 60.7% | 85.7% |

| Study | Domain 1: Study Eligibility Criteria | Domain 2: Identification and Selection of Studies | Domain 3: Data Collection and Study Appraisal | Domain 4: Synthesis and Findings | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jeffery, 2019 [2] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Berian, 2017 [15] | Low | Low | Low | Low/unclear | Low |

| Kotronoulas, 2017 [24] | Low | Low | Low | High | Low |

| Study | Domain 1: Randomization Process | Domain 2: Deviation from Intervention | Domain 3: Missing Outcome Data | Domain 4: Measurement of Outcome | Domain 5: Reported Result | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augestad, 2013 [16] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Strand, 2011 [17] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Augestad, 2014 [21] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Study | Domain 1: Bias Due to Confounding | Domain 2: Bias Due to Selection of Participants | Domain 3: Bias in Measurement of Interventions | Domain 4: Bias Due to Departure of Interventions | Domain 5: Bias Due to Missing Data | Domain 6: Bias in Measurement of Outcomes | Domain 7: Bias in Selection of the Reported Results | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coebergh van den Braak, 2018 [18] Prospective | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Wieldraaijer, 2018 [19] Retrospective | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Duinveld, 2016 [22] Retrospective | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

References

- Brenner, D.R.; Weir, H.K.; Demers, A.A.; Ellison, L.F.; Louzado, C.; Shaw, A.; Turner, D.; Woods, R.R.; Smith, L.M. Projected estimates of cancer in Canada in 2020. CMAJ 2020, 192, E199–E205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jeffery, M.; Hickey, B.E.; Hider, P.N. Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non- metastatic colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 9, CD002200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, K.D.; Syrjala, K.L.; Andrykowski, M.A. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer 2008, 112 (Suppl. S11), 2577–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, J.V.-T.; Matusko, N.; Hendren, S.; Regenbogen, S.E.; Hardiman, K.M. Patient-Reported Unmet Needs in Colorectal Cancer Survivors After Treatment for Curative Intent. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2019, 62, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browman, G.P.; Levine, M.N.; Mohide, E.A.; Hayward, R.S.; Pritchard, K.I.; Gafni, A.; Laupacis, A. The practice guidelines development cycle: A conceptual tool for practice guidelines development and implementation. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995, 13, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browman, G.P.; Newman, T.E.; Mohide, E.A.; Graham, I.D.; Levine, M.N.; Pritchard, K.I.; Evans, W.K.; Maroun, J.A.; Hodson, D.I.; Carey, M.S.; et al. Progress of clinical oncology guidelines development using the Practice Guidelines Development Cycle: The role of practitioner feedback. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Kho, M.E.; Browman, G.P.; Burgers, J.S.; Cluzeau, F.; Feder, G.; Fervers, B.; Graham, I.D.; Grimshaw, J.; Hanna, S.E.; et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010, 182, E839–E842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Members of the Colorectal Cancer Survivorship Group. Follow-Up Care, Surveillance Protocol, and Secondary Prevention Measures for Survivors of Colorectal Cancer; Program in Evidence-based Care Evidence-Based Series No.: 26-2 Version 2; Cancer Care Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012.

- Whiting, P.; Savović, J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Caldwell, D.M.; Reeves, B.C.; Shea, B.; Davies, P.; Kleijnen, J.; Churchill, R.; ROBIS Group. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 69, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Reeves, B.C. On Behalf of the Development Group for ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions, Version 7 March 2016. Available online: http://riskofbias.info (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Schünemann, H.; Brozek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D. Handbook for Grading the Quality of Evidence and the Strength of Recommendations Using the GRADE Approach. 2013. Available online: http://gradepro.org (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Cancer Council Australia Colorectal Cancer Guidelines Working Party. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention, Early Detection and Management of Colorectal Cancer; Cancer Council Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australiawiki/index.php?oldid=208059 (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Benson, A.B.; Venook, A.P.; Al-Hawary, M.M.; Cederquist, L.; Chen, Y.J.; Ciombor, K.K.; Cohen, S.; Cooper, H.S.; Deming, D.; Engstrom, P.F.; et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights Colon Cancer, Version 2.2018 Featured Updates to the NCCN Guidelines. JNCCN 2018, 16, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berian, J.R.; Cuddy, A.; Francescatti, A.B.; O’dwyer, L.; You, Y.N.; Volk, R.J.; Chang, G.J. A systematic review of patient perspectives on surveillance after colorectal cancer treatment. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augestad, K.M.; Norum, J.; Dehof, S.; Aspevik, R.; Ringberg, U.; Nestvold, T.; Vonen, B.; Skrøvseth, S.O.; Lindsetmo, R.-O. Cost-effectiveness and quality of life in surgeon versus general practitioner-organised colon cancer surveillance: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Strand, E.; Nygren, I.; Bergkvist, L.; Smedh, K. Nurse or surgeon follow-up after rectal cancer: A randomized trial. Colorectal Dis. 2011, 13, 999–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coebergh van den Braak, R.R.J.; Lalmahomed, Z.S.; Buttner, S.; Hansen, B.E.; Ijzermans, J.N.M.; on behalf of the MATCH Study Group. Nonphysician Clinicians in the Follow-Up of Resected Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Dig. Dis. 2018, 36, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieldraaijer, T.; Duineveld, L.A.M.; Donkervoort, S.C.; Busschers, W.B.; van Weert, H.; Wind, J. Colorectal cancer patients’ preferences for type of caregiver during survivorship care. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2018, 36, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pita-Fernandez, S.; Alhayek-Ai, M.; Gonzalez-Martin, C.; Lopez-Calvino, B.; Seoane-Pillado, T.; Pertega-Diaz, S. Intensive follow-up strategies improve outcomes in nonmetastatic colorectal cancer patients after curative surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augestad, K.M.; Norum, J.; Rose, J.; Lindsetmo, R.O. A prospective analysis of false positive events in a National Colon Cancer Surveillance Program. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duineveld, L.A.M.; Van Asselt, K.M.; Bemelman, W.A.; Smits, A.B.; Tanis, P.; Van Weert, H.C.P.M.; Wind, J. Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Colon Cancer Recurrence: A Multicenter Cohort Study. Ann. Fam. Med. 2016, 14, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bastiaenen, V.P.; Hovdenak Jakobsen, I.; Labianca, R.; Martling, A.; Morton, D.G.; Primrose, J.N.; Tanis, P.J.; Laurberg, S.; Research Committee and the Guidelines Committee of the European Society of Coloproctology (ESCP). Consensus and controversies regarding follow-up after treatment with curative intent of nonmetastatic colorectal cancer: A synopsis of guidelines used in countries represented in the European Society of Coloproctology. Colorectal Dis. 2019, 21, 392–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kotronoulas, G.; Papadopoulou, C.; Burns-Cunningham, K.; Simpson, M.; Maguire, R. A systematic review of the supportive care needs of people living with and beyond cancer of the colon and/or rectum. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 29, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qaderi, S.M.; Swartjes, H.; Custers, J.A.E.; de Wilt, J.H.W. Health care provider and patient preparedness for alternative colorectal cancer follow-up; a review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 1779–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sign or Symptom 1 | Type of Recurrence 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Local | Distant 3 | |

| Abdominal pain | X | X |

| Dry cough | X | |

| Rectal bleeding | X | |

| Changes in bowel habit | X | |

| Fatigue | X | X |

| Nausea | X | X |

| Unexplained weight loss | X | X |

| Anemia | X | X |

| Pain | X | |

| Stoma bleeding | X | |

| Palpable mass | X | X |

| Abdominal pain from hepatomegaly | X | |

| Jaundice | X | |

| Pleuritic chest pain or shortness of breath | X | |

| Anorexia, cachexia, and weight loss | X | |

| Dyspnea | X | |

| Loss of appetite | X | |

| Signs and/or symptoms specific to rectal cancer | ||

| Pelvic pain | X | |

| Sciatica | X | |

| Difficulty with urination or defecation | X | |

| Physical Long-term and Late Effects | |

| |

| Psychosocial Long-term and Late Effects | |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galica, J.; Zwaal, C.; Kennedy, E.; Asmis, T.; Cho, C.; Ginty, A.; Govindarajan, A. Models of Follow-Up Care and Secondary Prevention Measures for Survivors of Colorectal Cancer: Evidence-Based Guidelines and Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 439-454. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29020040

Galica J, Zwaal C, Kennedy E, Asmis T, Cho C, Ginty A, Govindarajan A. Models of Follow-Up Care and Secondary Prevention Measures for Survivors of Colorectal Cancer: Evidence-Based Guidelines and Systematic Review. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(2):439-454. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29020040

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalica, Jacqueline, Caroline Zwaal, Erin Kennedy, Tim Asmis, Charles Cho, Alexandra Ginty, and Anand Govindarajan. 2022. "Models of Follow-Up Care and Secondary Prevention Measures for Survivors of Colorectal Cancer: Evidence-Based Guidelines and Systematic Review" Current Oncology 29, no. 2: 439-454. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29020040

APA StyleGalica, J., Zwaal, C., Kennedy, E., Asmis, T., Cho, C., Ginty, A., & Govindarajan, A. (2022). Models of Follow-Up Care and Secondary Prevention Measures for Survivors of Colorectal Cancer: Evidence-Based Guidelines and Systematic Review. Current Oncology, 29(2), 439-454. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29020040