Patient-Factors Influencing the 2-Year Trajectory of Mental and Physical Health in Prostate Cancer Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

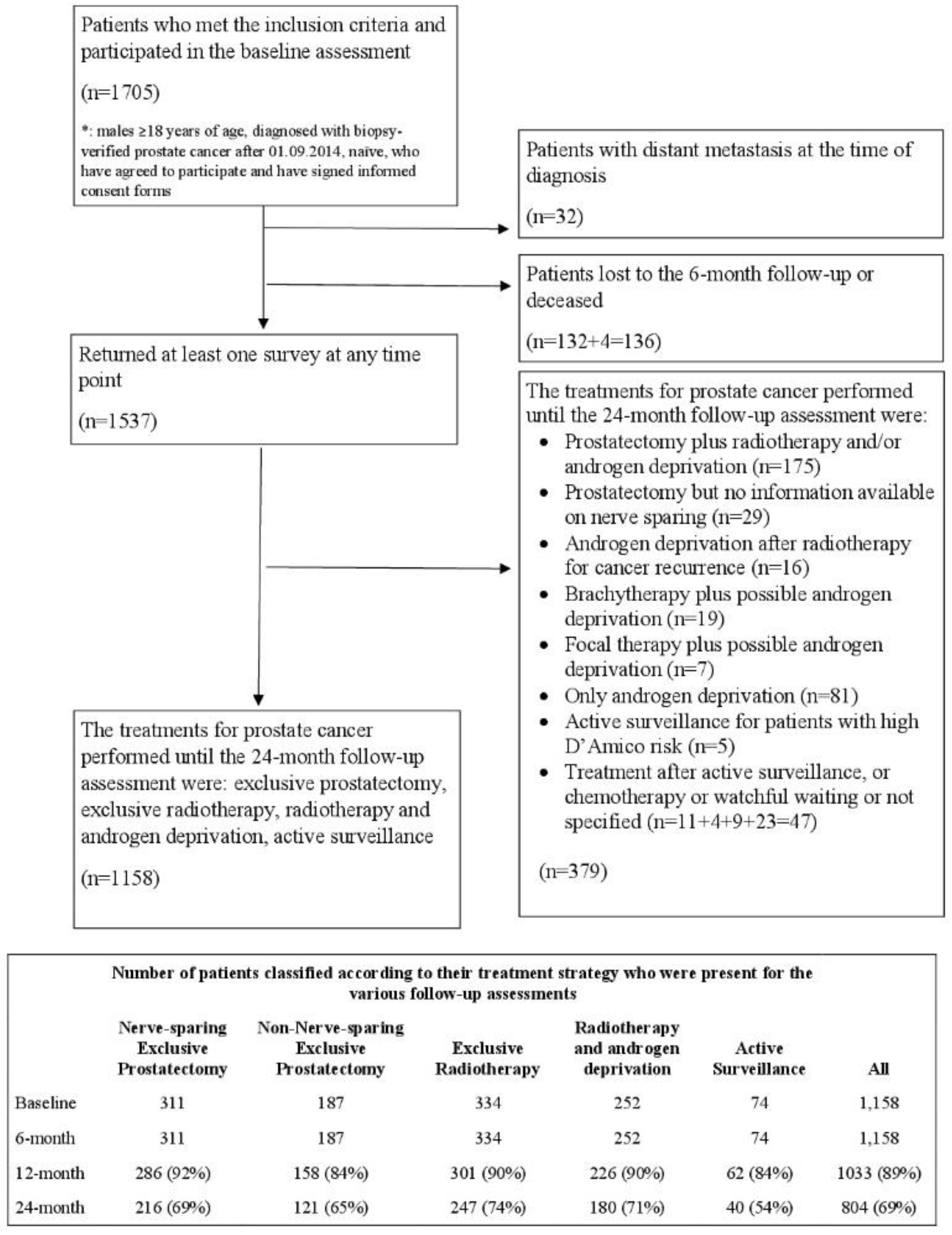

2.1. Participants

2.2. Outcome Variables

2.3. Predictor Variables

- Active surveillance (AS). The patients who did not remain in the group up to the 24-month follow-up were excluded;

- Nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy (NSRP);

- Non-nerve sparing exclusive radical prostatectomy (NNSRP);

- Exclusive radiotherapy (RT);

- Radiotherapy plus androgen deprivation therapy (RT plus ADT, not considering patients on ADT after radiotherapy for cancer recurrence).

2.4. External Comparison

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- the optimal number of groups was identified by fitting several models ranging from single to 5-group models;

- the shape of the trajectories was identified considering polynomials of varying degrees for each group, starting with a cubic specification, and then dropping non-significant polynomial terms;

- The model fit statistics (Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)), the value of group membership probability and the average posterior probability (entropy) were considered to identify the best model:

- ○

- the magnitude of the difference in the BIC (2ΔBIC > 10) was used to choose between less or more complex models.

- ○

- the analysis aimed to identify groups including at least 5% of the population;

- ○

- the average posterior probability of membership was ascertained for each group; values greater than 0.7 indicate adequate internal reliability.

3. Results

- a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05);

- a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in the mental or physical domain, i.e., how much of a difference in scores would result in some change in clinical management that is to be considered clinically meaningful [25]. Empirical findings from distribution based methods studies showed a tendency to converge to the ½ SD criteria as a meaningful moderate difference [26,27]. In the following analysis, we considered the conservative estimate approach by Sloan and colleagues for a minimum clinical important difference (MCID = 1 SD) from the patient’s perspectives [28,29]. This large effect size considers differences that overcome the limitations due to any subjective (the patient) and objective (the questionnaire) bias or error.

3.1. MCS Analysis

3.1.1. MCS at Diagnosis

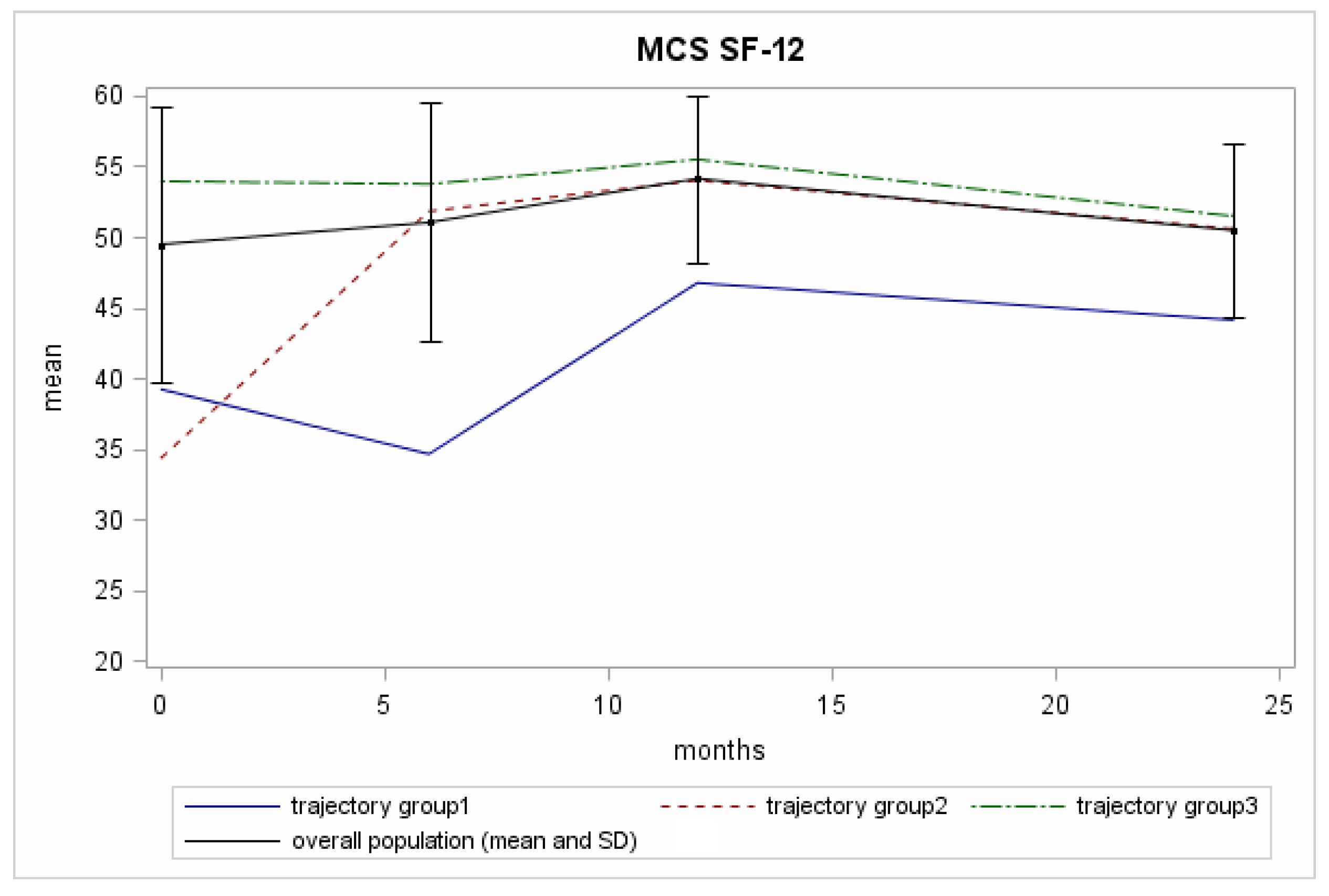

3.1.2. MCS over Time

- The “reference group” (Trajectory Group 3 (75% of the patients with GrMemb = 0.97)): the patients in this group showed constantly high scores throughout the 24-month follow-up period. BIM was 53.9, 2yrFU was 51.4.

- The “recovering group” (Trajectory Group 2 (12% of the patients with GrMemb = 0.87)): this group of patients started with low scores at diagnosis, then presented higher values at the 6-month follow-up, which they maintained until the end of the assessment. The difference between the baseline mean value for trajectory 2 members (34.3) and the total population mean value (49.3) exceeded the MCID. The mental health improvement exceeded the MCID in the first six-month follow-up, and then trajectory 2 members had normal range of values for the following follow-up time (Figure 2, black line).

- The “permanently low score group” (Trajectory Group 1 (13% of the patients with GrMemb = 0.92)): this group of patients started with low scores. The scores first fell to an even lower level and then surged upwards. BIM was 39.2, the nadir was 34.2, and the 2yrFU was 44.1. The difference with the total population mean value at the baseline exceeded the MCID. In contrast with the group 2 trajectory, the more considerable discrepancy was recorded at 6 months (34.2), where the average value for the population was 51.0.

3.2. PCS Analysis

3.2.1. PCS at Diagnosis

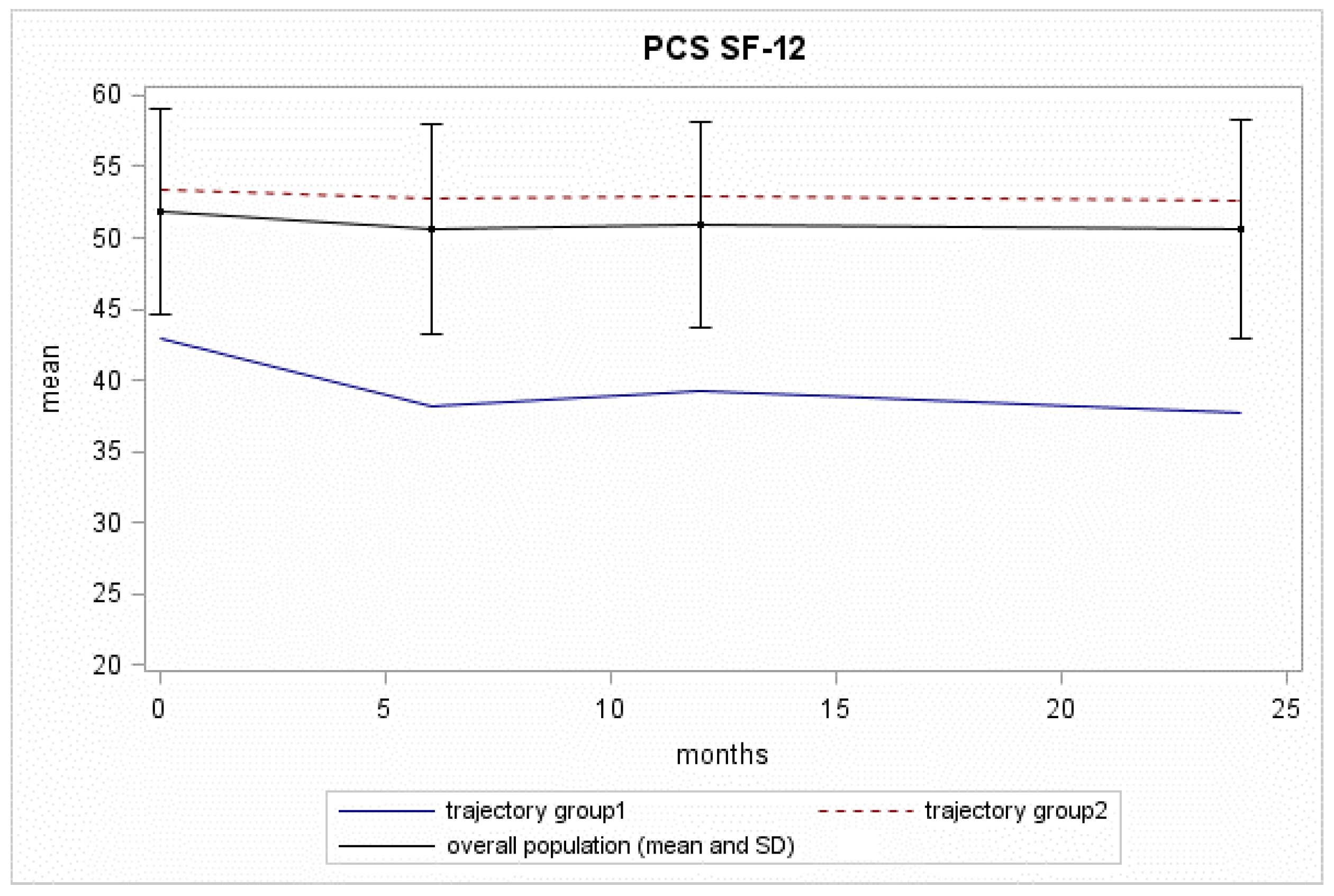

3.2.2. PCS over Time

- The “reference group” (Trajectory Group 2 (85% of the patients with GrMemb = 0.98)): this group of patients showed constantly high scores throughout the 24-month follow-up, with a BIM of 53.2, a 2yrFU of 52.6;

- The “decreasing group” (Trajectory Group 1 (15% of the patients with GrMemb = 0.92)): this group of patients started with low physical scores at diagnosis (BIM = 42.9). The scores fell to an even lower level at the 6-month follow-up, and they continued to decrease until the 24-month follow-up assessment (2yrFU = 37.7). The difference between the baseline mean value for this trajectory group and the overall mean exceeded the MCID. The decline with time increased the distance in PCS for these patients and the trajectory Group 2.

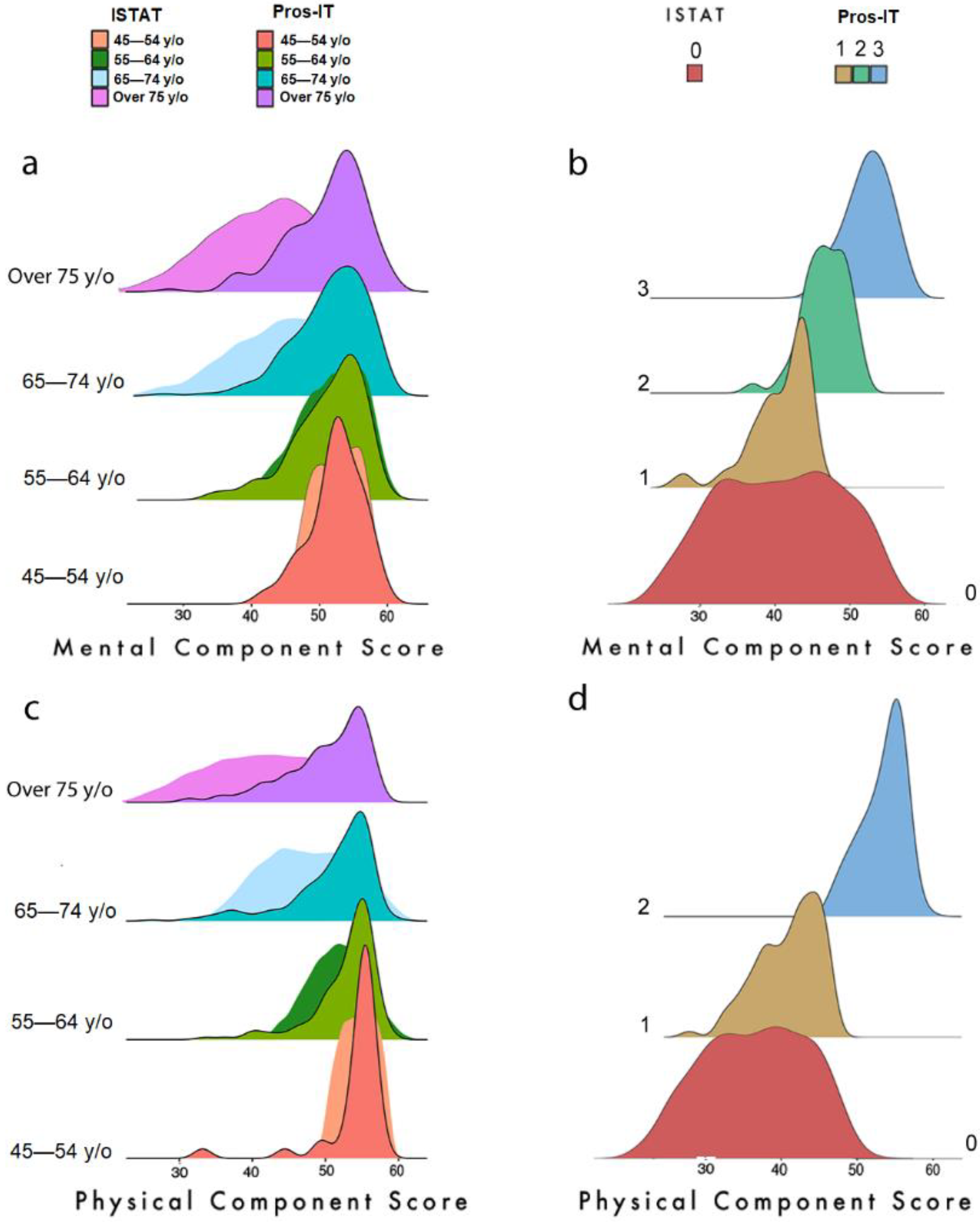

3.3. Health Status Comparison with the Italian Population Collected by the ISTAT

3.3.1. Age Groups in the Men (Tables S4 and S5)

3.3.2. Cancer Pathology (Tables S6 and S7)

3.3.3. Impact of Other Diseases on the MCS and PCS (Tables S8 and S9)

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with ISTAT Study

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collaboration GB of DC. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years for 29 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1553–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, N. Cancer survival data emphasise importance of early diagnosis. BMJ 2019, 364, l408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korfage, I.J.; Hak, T.; de Koning, H.J.; Essink-Bot, M.-L. Patients’ perceptions of the side-effects of prostate cancer treatment—A qualitative interview study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, S.K.; Ng, S.K.; Baade, P.; Aitken, J.F.; Hyde, M.K.; Wittert, G.; Frydenberg, M.; Dunn, J. Trajectories of quality of life, life satisfaction, and psychological adjustment after prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa, A.; Sonavane, S.; Mehta, J. Psychological aspects of prostate cancer: A clinical review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012, 15, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korfage, I.J.; Essink-Bot, M.-L.; Janssens, A.C.; Schröder, F.H.; De Koning, H.J. Anxiety and depression after prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment: 5-year follow-up. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 94, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, S.; Leydon, G.; Birch, B.; Prescott, P.; Lai, L.; Eardley, S.; Lewith, G. Depression and anxiety in prostate cancer: A sys-tematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e003901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuypers, M.; Lamers, R.E.D.; Cornel, E.B.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; de Vries, M.; Kil, P.J.M. The impact of prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment decision-making on health-related quality of life before treatment onset. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 26, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, S.; Kendel, F.; Venderbos, L.; Rancati, T.; Bangma, C.; Carroll, P.; Denis, L.; Klotz, L.; Korfage, I.J.; Lane, A.J.; et al. Setting an Agenda for Assessment of Health-related Quality of Life Among Men with Prostate Cancer on Active Surveillance: A Consensus Paper from a European School of Oncology Task Force. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellardita, L.; Valdagni, R.; Bergh, R.V.D.; Randsdorp, H.; Repetto, C.; Venderbos, L.D.; Lane, J.A.; Korfage, I.J. How Does Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer Affect Quality of Life? A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.; Shinkins, B.; Frith, E.; Neal, D.; Hamdy, F.; Walter, F.; Weller, D.; Wilkinson, C.; Faithfull, S.; Wolstenholme, J.; et al. Symptoms, unmet needs, psychological well-being and health status in survivors of prostate cancer: Implications for rede-signing follow-up. BJU Int. 2016, 117, E10–E19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, N.; Grimm, K.J. Growth Mixture Modeling: A Method for Identifying Differences in Longitudinal Change Among Un-observed Groups. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.-Y.; Sawatzky, R.; Baumbusch, J.; Lauck, S.; Ratner, P.A. Growth mixture models: A case example of the longitudinal analysis of patient-reported outcomes data captured by a clinical registry. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombard, Y.; Baker, G.R.; Orlando, E.; Fancott, C.; Bhatia, P.; Casalino, S.; Onate, K.; Denis, J.-L.; Pomey, M.-P. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noale, M.; Maggi, S.; Artibani, W.; Bassi, P.F.; Bertoni, F.; Bracarda, S.; Conti, G.N.; Corvò, R.; Gacci, M.; Graziotti, P.; et al. Pros-IT CNR: An Italian prostate cancer monitoring project. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 29, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porreca, A.; Noale, M.; Artibani, W.; Bassi, P.F.; Bertoni, F.; Bracarda, S.; Conti, G.N.; Corvò, R.; Gacci, M.; Graziotti, P.; et al. Disease-specific and general health-related quality of life in newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients: The Pros-IT CNR study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolone, G.; Mosconi, P.Q.L. Questionario Sullo Stato di Salute SF-12. Versione Italiana; Guerini e Associati Editori: Milano, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gandek, B.; Ware, J.E.; Aaronson, N.K.; Apolone, G.; Bjorner, J.B.; Brazier, J.E.; Bullinger, M.; Kaasa, S.; Leplege, A.; Prieto, L.; et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the sf-12 health survey in nine countries: Results from the iqola project. International quality of life assessment. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamoen, E.H.; De Rooij, M.; Witjes, J.A.; Barentsz, J.O.; Rovers, M.M. Measuring health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer: A systematic review of the most used questionnaires and their validity. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2015, 33, 69.e19–69.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacci, M.; Livi, L.; Paiar, F.; Detti, B.; Litwin, M.; Bartoletti, R.; Giubilei, G.; Cai, T.; Mariani, M.; Carini, M. Quality of life after radical treatment of prostate cancer: Validation of the Italian version of the University of California-Los Angeles Prostate Cancer Index. Urology 2005, 66, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andruff, H.; Carraro, N.; Thompson, A.; Gaudreau, P.; Louvet, B. Latent Class Growth Modelling: A tutorial. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2009, 5, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguena Nguefack, H.L.; Pagé, M.G.; Katz, J.; Choinière, M.; Vanasse, A.; Dorais, M.; Samb, O.M.; Lacasse, A. Trajectory Modelling Techniques Useful to Epidemiological Research: A Comparative Narrative Review of Approaches. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 12, 1205–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.L.; Nagin, D.S.; Roeder, K. A SAS Procedure Based on Mixture Models for Estimating Developmental Trajectories. Sociol. Methods Res. 2001, 29, 374–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noale, M.; Bruni, A.; Triggiani, L.; Buglione, M.; Bertoni, F.; Frassinelli, L.; Montironi, R.; Corvò, R.; Zagonel, V.; Porreca, A.; et al. Impact of Gastrointestinal Side Effects on Patients’ Reported Quality of Life Trajectories after Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer: Data from the Prospective, Observational Pros-IT CNR Study. Cancers 2021, 13, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeschke, R.; Singer, J.; Guyatt, G.H. Measurement of health status: Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control. Clin. Trials 1989, 10, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osoba, D. The clinical value and meaning of health related quality-of-life outcomes in oncology. In Outcomes Assessment in Cancer; Lipscomb, J., Gotay, C., Snyder, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 386–405. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, G.R.; Sloan, J.A.; Wyrwich, K.W. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med. Care 2003, 41, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, J.; Symonds, T.; Vargas, D.; Fridley, B. Practical Guidelines for Assessing the Clinical Significance of Health-Related Quality of Life Changes within Clinical Trials. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2003, 37, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, J.A. Assessing the Minimally Clinically Significant Difference: Scientific Considerations, Challenges and Solutions. COPD: J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2005, 2, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sefik, E.; Gunlusoy, B.; EKER, A.; Celik, S.; Ceylan, Y.; Koskderelioglu, A.; Basmaci, I.; Degirmenci, T. Anxiety and depression associated with a positive prostate biopsy result: A comparative, prospective cohort study. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2020, 46, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dordoni, P.; Badenchini, F.; Alvisi, M.F.; Menichetti, J.; De Luca, L.; Di Florio, T.; Magnani, T.; Marenghi, C.; Rancati, T.; Valdagni, R.; et al. How do prostate cancer patients navigate the active surveillance journey? A 3-year longitudinal study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, S.; Love, A.; MacVean, M.; Duchesne, G.; Couper, J.; Kissane, D. Psychological adjustment of men with prostate cancer: A review of the literature. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2007, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyi, Z.; Szluha, K.; Nemes, L.; Kovács, S.; Bugán, A. Positive consequences of cancer: Exploring relationships among post-traumatic growth, adult attachment, and quality of life. Tumori 2015, 101, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurian, C.J.; Leader, A.E.; Thong, M.S.Y.; Keith, S.W.; Zeigler-Johnson, C.M. Examining relationships between age at diagnosis and health-related quality of life outcomes in prostate cancer survivors. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farris, M.S.; Kopciuk, K.A.; Courneya, K.S.; McGregor, S.E.; Wang, Q.; Friedenreich, C.M. Identification and prediction of health-related quality of life trajectories after a prostate cancer diagnosis. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punnen, S.; Cowan, J.E.; Chan, J.M.; Carroll, P.R.; Cooperberg, M.R. Long-term Health-related Quality of Life After Primary Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer: Results from the CaPSURE Registry. Eur. Urol. 2015, 68, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, K.E.; Penson, D.F.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, L.-C.; Conwill, R.; Laviana, A.A.; Joyce, D.D.; Luckenbaugh, A.N.; Goodman, M.; Hamilton, A.S.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes Through 5 Years for Active Surveillance, Surgery, Brachytherapy, or External Beam Radiation With or Without Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. JAMA 2020, 323, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.L.; Hamdy, F.C.; Lane, J.A.; Mason, M.; Metcalfe, C.; Walsh, E.; Blazeby, J.M.; Peters, T.J.; Holding, P.; Bonnington, S.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Guedea, F.; Suárez, J.F.; de Paula, B.; Macias, V.; Mariño, A.; Hervás, A.; Herruzo, I.; Ortiz, M.J.; de León, J.P.; et al. Quality of life impact of treatments for localized prostate cancer: Cohort study with a 5year follow-up. Radiother. Oncol. 2013, 108, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissers, P.A.J.; Falzon, L.; Van De Poll-Franse, L.V.; Pouwer, F.; Thong, M.S.Y. The impact of having both cancer and diabetes on patient-reported outcomes: A systematic review and directions for future research. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 10, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, D.S. Importance of glycemic control in cancer patients with diabetes: Treatment through end of life. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 4, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, M.S.; Van De Poll-Franse, L.; Hoffman, R.M.; Albertsen, P.C.; Hamilton, A.S.; Stanford, J.L.; Penson, D.F. Diabetes mellitus and health-related quality of life in prostate cancer: 5-year results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. Br. J. Urol. 2010, 107, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, B.B.; Chen, R.C.; Moore, D.T.; Deal, A.M.; Usinger, D.S.; Lyons, J.C.; Talcott, J.A. Impact of comorbidity on health-related quality of life after prostate cancer treatment: Combined analysis of two prospective cohort studies. Br. J. Urol. 2014, 114, E74–E81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sureda, A.; Fumadó, L.; Ferrer, M.; Garín, O.; Bonet, X.; Castells, M.; Mir, M.C.; Abascal, J.M.; Vigués, F.; Cecchini, L.; et al. Health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance versus radical prostatectomy, external-beam radiotherapy, prostate brachytherapy and reference population: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AIOM; AIRTUM S-I. I Numeri del Cancro in Italia; Intermedia Editore: Brescia, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.P.; Wong, C.K.; Wan, E.Y.; Tsu, J.H.; Chin, W.Y.; Kung, K.; Yiu, M.K. The internal and external responsiveness of Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate (FACT-P) and Short Form-12 Health Survey version 2 (SF-12 v2) in patients with prostate cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 2379–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall (n = 1158) | Nerve-Sparing Exclusive Prostatectomy (n = 311) | Non- Nerve-Sparing Exclusive Prostatectomy (n = 187) | Exclusive Radiotherapy (n = 334) | Radiotherapy and Androgen Deprivation (n = 252) | Active Surveillance (n = 74) | p- Value § | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean ± SD | 68.8 ± 7.4 | 63.2 ± 6.8 | 66.9 ± 6.1 | 72.8 ± 5.2 | 72.5 ± 5.9 | 66.9 ± 6.5 | <0.0001 |

| Education > lower secondary school, n (%) | 562 (49.2) | 178 (57.6) | 100 (53.8) | 144 (43.6) | 97 (39.8) | 43 (58.1) | <0.0001 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, n (%) | 177 (15.6) | 34 (11.1) | 29 (15.5) | 56 (17.1) | 50 (21.0) | 8 (10.8) | 0.0179 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 166 (14.6) | 48 (15.8) | 35 (18.9) | 43 (13.2) | 29 (11.7) | 11 (15.3) | 0.2554 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 172 (14.9) | 23 (7.4) | 28 (15.0) | 57 (17.2) | 59 (23.4) | 5 (6.8) | <0.0001 |

| 3 + moderate/severe comorbidities *, n (%) | 174 (15.0) | 32 (10.3) | 22 (11.8) | 59 (17.7) | 50 (19.9) | 11 (14.9) | 0.0089 |

| Family history of prostate cancer, n (%) | 187 (16.3) | 71 (23.1) | 32 (17.5) | 39 (11.7) | 37 (15.0) | 8 (10.8) | 0.0015 |

| T staging at diagnosis, n (%) T1 T2 T3 or T4 | 557 (50.2) 445 (40.1) 107 (9.7) | 200 (65.6) 102 (33.4) 3 (1.0) | 97 (55.4) 72 (41.2) 6 (3.4) | 131 (41.6) 150 (47.6) 34 (10.8) | 63 (25.9) 116 (47.8) 64 (26.3) | 66 (93.0) 5 (7.0) 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 |

| Gleason score at diagnosis, n (%) ≤6 3 + 4 4 + 3 ≥8 | 535 (46.6) 279 (24.3) 157 (13.7) 177 (15.4) | 186 (60.0) 78 (25.2) 27 (8.7) 19 (6.1) | 76 (40.9) 49 (26.3) 36 (19.4) 25 (13.4) | 155 (47.1) 86 (26.1) 47 (14.3) 41 (12.5) | 48 (19.1) 65 (25.9) 46 (18.3) 92 (36.7) | 70 (98.6) 1 (1.4) 1 (1.4) 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 |

| PSA at diagnosis, ng/mL, median (Q1, Q3) | 7 (5.1, 10) | 6.3 (5, 8.7) | 6.9 (5.1, 10) | 7 (5.1, 9.9) | 8.9 (6.3, 14.3) | 6.2 (4.9, 7.7) | <0.0001 |

| D’Amico risk class, n (%) Low Intermediate High | 303 (26.7) 494 (43.5) 338 (29.8) | 120 (39.1) 152 (49.5) 35 (11.4) | 43 (23.6) 97 (53.3) 42 (23.1) | 70 (21.4) 146 (44.7) 111 (33.9) | 10 (4.0) 89 (35.7) 150 (60.3) | 60 (85.7) 10 (14.3) 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 |

| UCLA PCI UF, mean ± SD | 93.7 ± 15.1 | 96.5 ± 10.7 | 94.2 ± 15.0 | 91.9 ± 17.1 | 92.4 ± 16.5 | 93.8 ± 15.0 | 0.0006 |

| UCLA PCI UB, mean ± SD | 89.1 ± 22.7 | 92.8 ± 20.0 | 92.3 ± 19.5 | 86.2 ± 24.5 | 84.7 ± 25.8 | 92.5 ± 17.0 | <0.0001 |

| UCLA PCI BF, mean ± SD | 93.6 ± 13.4 | 96.1 ± 9.3 | 94.3 ± 12.9 | 91.7 ± 15.4 | 91.8 ± 15.0 | 94.5 ± 12.6 | 0.0004 |

| UCLA PCI BB, mean ± SD | 93.7 ± 17.6 | 92.3 ± 12.9 | 94.6 ± 16.0 | 92.9 ± 18.4 | 90.4 ± 22.7 | 95.9 ± 14.4 | 0.0100 |

| UCLA PCI SF, mean ± SD | 50.2 ± 31.7 | 66.6 ± 27.0 | 56.4 ± 29.2 | 37.9 ± 30.3 | 37.9 ± 29.2 | 61.1 ± 30.2 | <0.0001 |

| UCLA PCI SB, mean ± SD | 63.9 ± 34.8 | 71.8 ± 32.2 | 61.7 ± 35.1 | 58.7 ± 36.5 | 58.8 ± 34.8 | 75.7 ± 27.2 | <0.0001 |

| SF-12 PCS, mean ± SD | 51.9 ± 7.2 | 53.7 ± 5.7 | 52.6 ± 6.7 | 50.8 ± 7.8 | 50.2 ± 8.3 | 52.7 ± 6.1 | <0.0001 |

| SF-12 MCS, mean ± SD | 49.5 ± 9.7 | 49.3 ± 9.4 | 47.9 ± 10.0 | 50.2 ± 9.7 | 49.2 ± 9.9 | 50.9 ± 9.2 | 0.0300 |

| MCS SF-12 | Trajectory 2 vs. 3 | Trajectory 1 vs. 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 0.94 (0.91, 0.97) | 0.0003 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.2278 |

| Education > lower secondary school | 1.13 (0.76, 1.68) | 0.5417 | 1.34 (0.89, 2.00) | 0.1605 |

| Marital status, married vs widowed, divorced or never married | 1.39 (0.51, 3.80) | 0.5257 | 1.12 (0.44–2.82) | 0.8157 |

| Living arrangement, with other vs alone | 1.68 (0.52–5.46) | 0.3908 | 1.84 (0.64–5.28) | 0.2563 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 0.82 (0.68, 1.19) | 0.1784 | 1.04 (0.79, 1.38) | 0.9759 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.88 (0.61, 1.10) | 0.5628 | 1.00 (0.61, 1.70) | 0.9580 |

| Family history of prostate cancer | 1.87 (1.17, 2.99) | 0.0092 | 1.70 (1.03, 2.82) | 0.0392 |

| 3 + moderate/severe comorbidities * | 1.90 (1.16, 3.11) | 0.0112 | 1.86 (1.15, 3.02) | 0.0114 |

| Current smoker | 0.84 (0.48, 1.46) | 0.5327 | 1.27 (0.74, 2.17) | 0.3865 |

| D’Amico risk class, high vs. intermediate/low | 1.58 (1.00, 2.49) | 0.0501 | 0.95 (0.59, 1.51) | 0.8207 |

| Prostate cancer treatments | ||||

| NNSRP vs. NSRP | 1.23 (0.70, 2.14) | 0.4757 | 1.13 (0.55, 2.32) | 0.7350 |

| RT vs. NSRP | 0.69 (0.37, 1.27) | 0.2331 | 1.58 (0.82, 3.02) | 0.1716 |

| RT plus ADT vs. NSRP | 0.62 (0.30, 1.28) | 0.1927 | 1.83 (0.88, 3.84) | 0.1082 |

| AS vs. NSRP | 0.86 (0.35, 2.10) | 0.7435 | 1.84 (0.78, 4.35) | 0.1648 |

| Distance between the end of treatment and follow-up assessment, days | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) | 0.5037 | 1.05 (0.92, 1.10) | 0.7563 |

| UF at diagnosis §, highest quartile vs. lower 1 | 0.55 (0.35, 0.85) | 0.0075 | 0.52 (0.34,0.79) | 0.0024 |

| BF at diagnosis §, highest quartile vs. lower 2 | 0.43 (0.29, 0.65) | <0.0001 | 0.36 (0.24, 0.54) | <0.0001 |

| SF at diagnosis §, highest quartile vs. lower 3 | 0.48 (0.29, 0.80) | 0.0051 | 0.77 (0.45, 1.32) | 0.3369 |

| Class 2 vs. 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| PCS SF-12 | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 0.4128 |

| Education > lower secondary school | 0.99 (0.60, 1.65) | 0.9752 |

| Marital status, married vs widowed, divorced or never married | 1.02 (0.32, 3.30) | 0.9691 |

| Living arrangement, with other vs alone | 1.23 (0.33, 4.64) | 0.7632 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 0.97 (0.67, 1.40) | 0.8644 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1.99 (1.11, 3.59) | 0.0214 |

| Family history of prostate cancer | 1.02 (0.52, 2.03) | 0.9466 |

| 3 + moderate/severe comorbidities * | 1.23 (0.67, 2.26) | 0.5144 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 1.35 (0.65, 2.82) | 0.4193 |

| D’Amico risk class, high | 0.70 (0.40, 1.23) | 0.2142 |

| Prostate cancer treatments | ||

| NNSRP vs. NSRP | 1.05 (0.35, 3.15) | 0.9327 |

| ER vs. NSRP | 3.01 (1.24, 7.30) | 0.0150 |

| RT plus ADT vs. NSRP | 3.56 (1.18, 10.7) | 0.0246 |

| AS vs. NSRP | 1.19 (0.24, 5.96) | 0.8342 |

| Distance between the end of treatment and follow-up assessment, days | 1.06 (0.98, 1.13) | 0.6156 |

| UF at diagnosis §, highest quartile vs. lower 1 | 0.55 (0.33, 0.94) | 0.0284 |

| BF at diagnosis §, highest quartile vs. lower 2 | 0.47 (0.28, 0.78) | 0.0032 |

| SF at diagnosis §, highest quartile vs. lower 3 | 0.47 (0.21, 1.07) | 0.0727 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cicchetti, A.; Noale, M.; Dordoni, P.; Noris Chiorda, B.; De Luca, L.; Bellardita, L.; Montironi, R.; Bertoni, F.; Bassi, P.; Schiavina, R.; et al. Patient-Factors Influencing the 2-Year Trajectory of Mental and Physical Health in Prostate Cancer Patients. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 8244-8260. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110651

Cicchetti A, Noale M, Dordoni P, Noris Chiorda B, De Luca L, Bellardita L, Montironi R, Bertoni F, Bassi P, Schiavina R, et al. Patient-Factors Influencing the 2-Year Trajectory of Mental and Physical Health in Prostate Cancer Patients. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(11):8244-8260. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110651

Chicago/Turabian StyleCicchetti, Alessandro, Marianna Noale, Paola Dordoni, Barbara Noris Chiorda, Letizia De Luca, Lara Bellardita, Rodolfo Montironi, Filippo Bertoni, Pierfrancesco Bassi, Riccardo Schiavina, and et al. 2022. "Patient-Factors Influencing the 2-Year Trajectory of Mental and Physical Health in Prostate Cancer Patients" Current Oncology 29, no. 11: 8244-8260. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110651

APA StyleCicchetti, A., Noale, M., Dordoni, P., Noris Chiorda, B., De Luca, L., Bellardita, L., Montironi, R., Bertoni, F., Bassi, P., Schiavina, R., Gacci, M., Serni, S., Sessa, F., Maruzzo, M., Maggi, S., & Valdagni, R., on behalf of The Pros-IT CNR Study Group. (2022). Patient-Factors Influencing the 2-Year Trajectory of Mental and Physical Health in Prostate Cancer Patients. Current Oncology, 29(11), 8244-8260. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110651