A Survey of Older Adults’ Self-Managing Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment Procedure and Consent

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

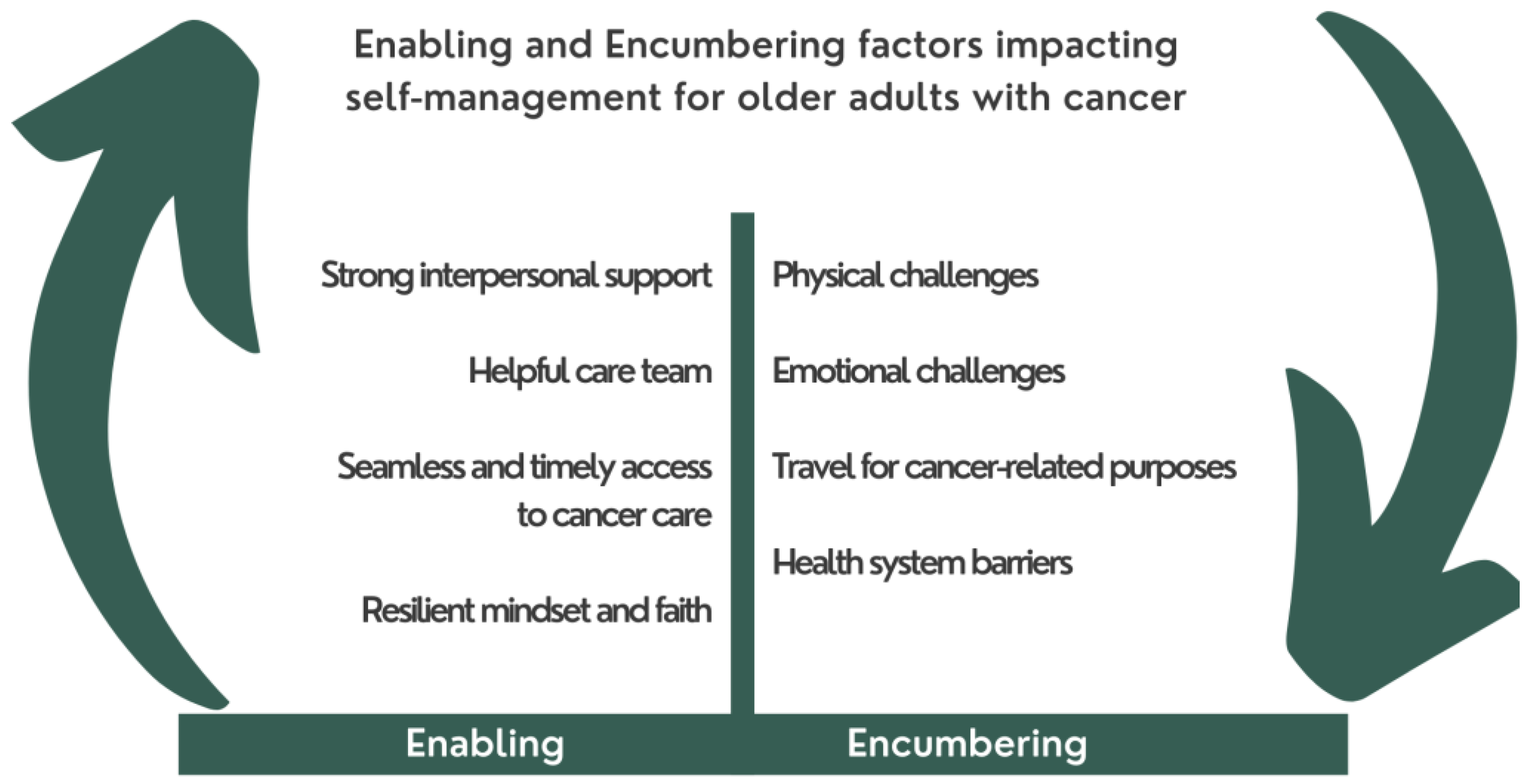

3.1. Thematic Analysis

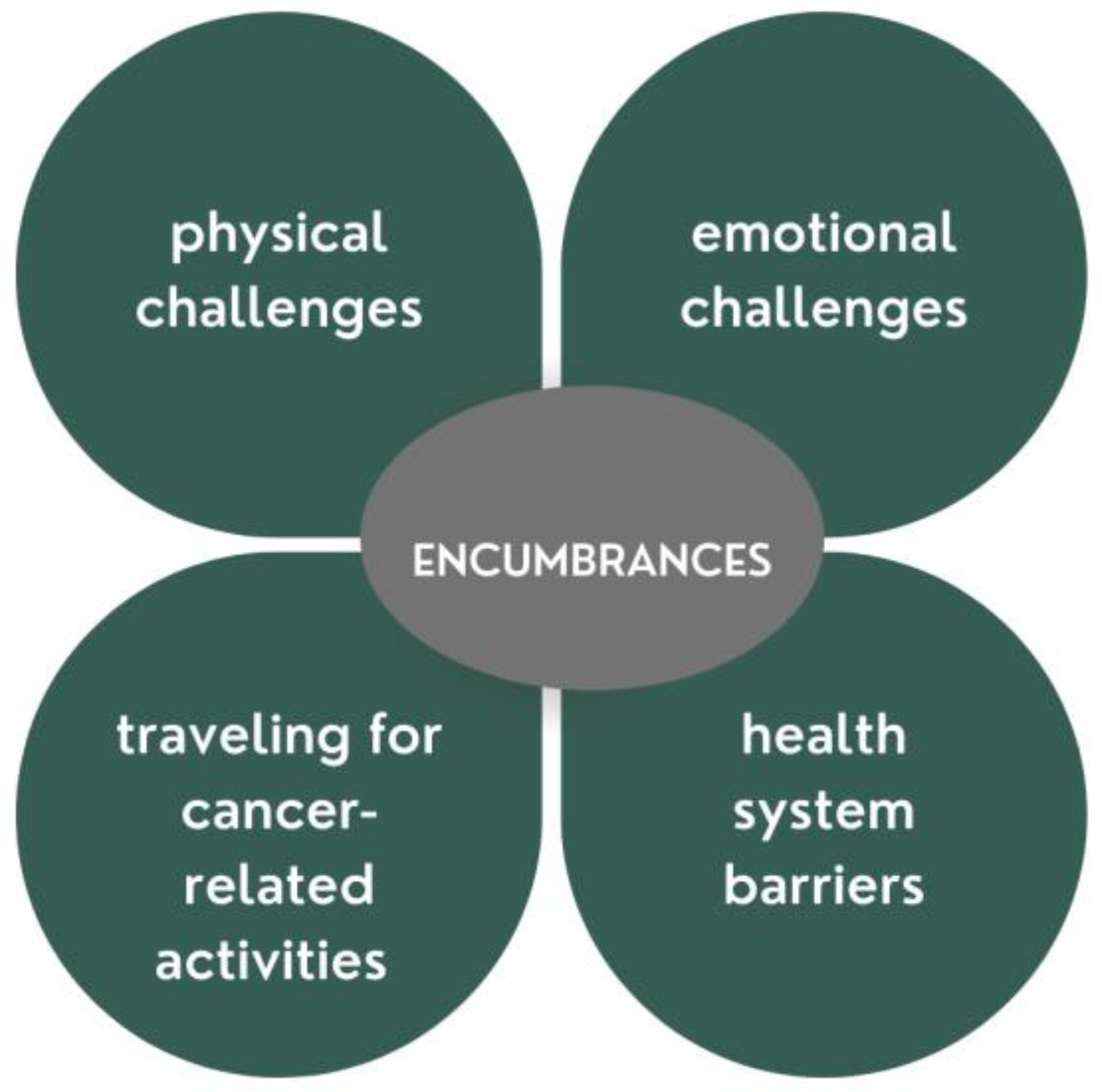

Encumbrances

- (1)

- Physical challenges to cancer self-management

- (2)

- Emotional Challenges

- (3)

- Travel for Cancer-Related Activities

- (4)

- Health System Barriers

3.2. Enablers

- (1)

- Strong interpersonal support

- (2)

- Supportive care team

- (3)

- Seamless and timely access to cancer care

- (4)

- Resilient mindset and faith

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pilleron, S.; Sarfati, D.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F.; Soerjomataram, I. Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: A population-based study. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 144, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Global Cancer Facts and Figures, 4th ed.; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Stout, N.L.; Wagner, S.S. Antineoplastic Therapy Side Effects and Polypharmacy in Older Adults With Cancer. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2019, 35, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markle-Reid, M.; Ploeg, J.; Fraser, K.D.; Fisher, K.A.; Bartholomew, A.; Griffith, L.E.; Miklavcic, J.; Gafni, A.; Thabane, L.; Upshur, R. Community Program Improves Quality of Life and Self-Management in Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus and Comorbidity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 66, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavers, D.; Habets, L.; Cunningham-Burley, S.; Watson, E.; Banks, E.; Campbell, C. Living with and beyond cancer with comorbid illness: A qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, H.; Belot, A.; Ellis, L.; Maringe, C.; Luque-Fernandez, M.A.; Njagi, E.N.; Navani, N.; Sarfati, D.; Rachet, B. Comorbidity prevalence among cancer patients: A population-based cohort study of four cancers. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, T.; Bridges, J. Multimorbidity in older adults living with and beyond cancer. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2019, 13, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D. Collaborate to Activate: Empowering Patients and Providers for Improved Self-Management. In Proceedings of the 2015 Signature Event of the Cancer Quality Council of Ontario, Toronto, ON, Canada, 5 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, D.; Mayer, D.K.; Fielding, R.; Eicher, M.; Leeuw, I.M.V.-D.; Johansen, C.; Soto-Perez-De-Celis, E.; Foster, C.; Chan, R.; Alfano, C.M.; et al. Management of Cancer and Health After the Clinic Visit: A Call to Action for Self-Management in Cancer Care. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 113, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.R.; Holman, H.R. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorkle, R.; Ercolano, E.; Lazenby, M.; Schulman-Green, D.; Schilling, L.S.; Lorig, K.; Wagner, E.H. Self-management: Enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, T.L.; Hallas, J.; Friis, S.; Herrstedt, J. Comorbidity in elderly cancer patients in relation to overall and cancer-specific mortality. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.R.; Ramsdale, E.; Loh, K.P.; Arastu, A.; Xu, H.; Obrecht, S.; Castillo, D.; Sharma, M.; Holmes, H.M.; Nightingale, G.; et al. Associations of Polypharmacy and Inappropriate Medications with Adverse Outcomes in Older Adults with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 2019, 25, e94–e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.; Loscalzo, M.; Ramani, R.; Forman, S.; Popplewell, L.; Clark, K.; Katheria, V.; Feng, T.; Aa, R.S.; Bs, R.R.; et al. Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Cancer 2014, 120, 2927–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Med, J.K.P.; Hasan, S.M.; Barnsley, J.; Berta, W.; Fazelzad, R.; Papadakos, C.J.; Giuliani, M.E.; Howell, D. Health literacy and cancer self-management behaviors: A scoping review. Cancer 2018, 124, 4202–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinsbekk, A.; Rygg, L.; Lisulo, M.; Rise, M.B.; Fretheim, A. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhwani, S.; Wodchis, W.P.; Zimmermann, C.; Moineddin, R.; Howell, D. Self-management, self-management support needs and interventions in advanced cancer: A scoping review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 9, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, S.; Williams, A. Promoting and supporting self-management for adults living in the community with physical chronic illness: A systematic review of the effectiveness and meaningfulness of the patient-practitioner encounter. JBI Evid. Synth. 2009, 7, 492–582. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, C.; Fenlon, D. Recovery and self-management support following primary cancer treatment. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 105, S21–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, K.; Chowdhury, S.; Kelly, J. Design, conduct, and analysis of random-digit dialing surveys. In Handbook of Statistics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis: A practical guide. In Thematic Analysis; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mohile, S.G.; Dale, W.; Somerfield, M.R.; Schonberg, M.A.; Boyd, C.M.; Burhenn, P.; Canin, B.; Cohen, H.J.; Holmes, H.M.; Hopkins, J.O.; et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2326–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, W. Why Is Geriatric Assessment so Infrequently Used in Oncology Practices? The Ongoing Issue of Nonadherence to This Standard of Care for Older Adults With Cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2022, 18, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D. Self-Management in Cancer: Quality Standards in Patient Education; Cancer Care Ontario: Ontario, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Puts, M.; Strohschein, F.; Oldenmenger, W.; Haase, K.; Newton, L.; Fitch, M.; Sattar, S.; Stolz-Baskett, P.; Jin, R.; Loucks, A.; et al. Position statement on oncology and cancer nursing care for older adults with cancer and their caregivers of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology Nursing and Allied Health Interest Group, the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology Oncology & Aging Special Interest Group, and the European Oncology Nursing Society. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, D. Managing one’s body using self-management techniques: Practicing autonomy. Theor. Med. Bioeth. 2000, 21, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R.; Sánchez-Izquierdo, M.; Olmos, R.; Huici, C.; Ribera Casado, J.M.; Cruz Jentoft, A. Paternalism vs. autonomy: Are they alternative types of formal care? Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildiers, H.; Heeren, P.; Puts, M.; Topinkova, E.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.; Extermann, M.; Falandry, C.; Artz, A.; Brain, E.; Colloca, G.; et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology Consensus on Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients With Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2595–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sourdet, S.; Brechemier, D.; Steinmeyer, Z.; Gerard, S.; Balardy, L. Impact of the comprehensive geriatric assessment on treatment decision in geriatric oncology. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, M.; Lund, C.; Molder, M.T.; Soubeyran, P.; Wildiers, H.; van Huis, L.; Rostoft, S. Geriatric assessment in the management of older patients with cancer—A systematic review (update). J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Davis, C.L.; Funnell, M.M.; Beck, A. Implementing practical interventions to support chronic illness self-management. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Saf. 2003, 29, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.; Steed, L.; Mulligan, K. Self-management interventions for chronic illness. Lancet 2004, 364, 1523–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Data Tables, 2016 Census: Visible Minority (15), Generation Status (4), Age (12) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 census-25% Sample Data. 2019. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/dt-td/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=7&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=112451&PRID=10&PTYPE=109445&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2016,2017&THEME=0&VID=0&VNAMEE=Age%20%2815A%29&VNAMEF=%C3%82ge%20%2815A%29 (accessed on 11 October 2022).

| Age (years) | Median 76 (IQR 11) Range 65–93 * |

| Women | 67 (51.9%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 118 (91.5%) |

| Asian | 2 (1.6%) |

| Latin American | 1 (<1%) |

| Mixed racial background | 1 (<1%) |

| Other | 5 (3.9%) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 2 (1.6%) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Some high school | 8 (6.2%) |

| High school graduate | 32 (24.8%) |

| Classes towards technical/college course/university or degree completion | 86 (66.6%) |

| Total household income for 2021 | |

| <$25,000 | 12 (9.3%) |

| $25,000–<$50,000 | 17 (13.2%) |

| $50,000–<$75,000 | 13 (10.1%) |

| $75,000–<$100,000 | 14 (10.9%) |

| $100,000–<$125,000 | 33 (25.7%) |

| Don’t know | 16 (12.4%) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 34 (26.4%) |

| Years since diagnosis | Median 2.5 (IQR 7) Range 0–45 ** |

| Cancer sites | |

| Prostate | 31 (24%) |

| Breast | 18 (14%) |

| Skin | 15(11.6%) |

| Colorectal | 11 (8.5%) |

| Hematological | 11 (8.5%) |

| Lung | 8 (6.2%) |

| Gynecological | 7 (5.4%) |

| Head and neck | 6 (4.7%) |

| Bladder | 5 (3.9%) |

| Kidney | 4 (3.1) |

| Liver | 3 (2.3%) |

| Pancreatic | 1 (<1%) |

| Other | 7 (5.4%) |

| On cancer treatment/received treatment in past 12 months | 77 (59.7%) |

| Treatment type | |

| Chemotherapy | 19 (14.7%) |

| Radiation | 17 (13.2%) |

| Endocrine | 13 (10.0%) |

| Surgery | 32 (24.8%) |

| Other | 26 (20.1%) |

| Have other illnesses | 66 (51.2%) |

| Finances a barrier to cancer management | 5 (3.9%) |

| Had challenges managing cancer treatment and appointments | 26 (20.2%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haase, K.R.; Sattar, S.; Dhillon, S.; Kilgour, H.M.; Pesut, J.; Howell, D.; Oliffe, J.L. A Survey of Older Adults’ Self-Managing Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 8019-8030. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110634

Haase KR, Sattar S, Dhillon S, Kilgour HM, Pesut J, Howell D, Oliffe JL. A Survey of Older Adults’ Self-Managing Cancer. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(11):8019-8030. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110634

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaase, Kristen R., Schroder Sattar, Sandeep Dhillon, Heather M. Kilgour, Jennifer Pesut, Doris Howell, and John L. Oliffe. 2022. "A Survey of Older Adults’ Self-Managing Cancer" Current Oncology 29, no. 11: 8019-8030. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110634

APA StyleHaase, K. R., Sattar, S., Dhillon, S., Kilgour, H. M., Pesut, J., Howell, D., & Oliffe, J. L. (2022). A Survey of Older Adults’ Self-Managing Cancer. Current Oncology, 29(11), 8019-8030. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110634