Introduction

Scimitar syndrome is a rare congenital heart anomaly first described in 1836 by Cooper and Chassina [

1]. The estimated incidence is about 2/100 000 [

2]. Presenting a subtype of a partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection (PAPVC), it is defined as complete or partial anomalous drainage of the right pulmonary veins into the inferior vena cava. This results in a left-to-right shunt. Scimitar meaning “curved Turkish sabre” derives from the typical radiological sign produced by the anomalous right pulmonary vein draining into the inferior vena cava [

3]. Multiple cardiac anomalies can be associated with this syndrome. Hypoplasia of the right lung is present in virtually all cases in varying degrees. Furthermore, dextroversion of the heart, hypoplasia of the right pulmonary artery, aortopulmonary collaterals as well as an atrial septal defect (ASD) with a prevalence up to 60% [

4,

5] may be present.

In terms of clinical presentation two forms of scimitar syndrome [

6] need to be distinguished.

Firstly, the infantile form, which is associated with significant mortality. Neonates and infants show respiratory distress, signs of heart failure, right lung hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension as findings raising suspicion of this syndrome.

Secondly, the juvenile and adult form, presenting in late childhood or adulthood, is often detected by accident and patients are mostly oligo-to asymptomatic [

1].

We are presenting a case of an adult form of scimitar syndrome showing only mild symptoms and typical diagnostic findings.

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old female presented with progressive dyspnoea and no significant co-morbidities. An X-ray at the age of 19 years had already shown cardiomegaly and strong physical efforts were not possible throughout her life. Nevertheless, no further examinations had been performed in the past.

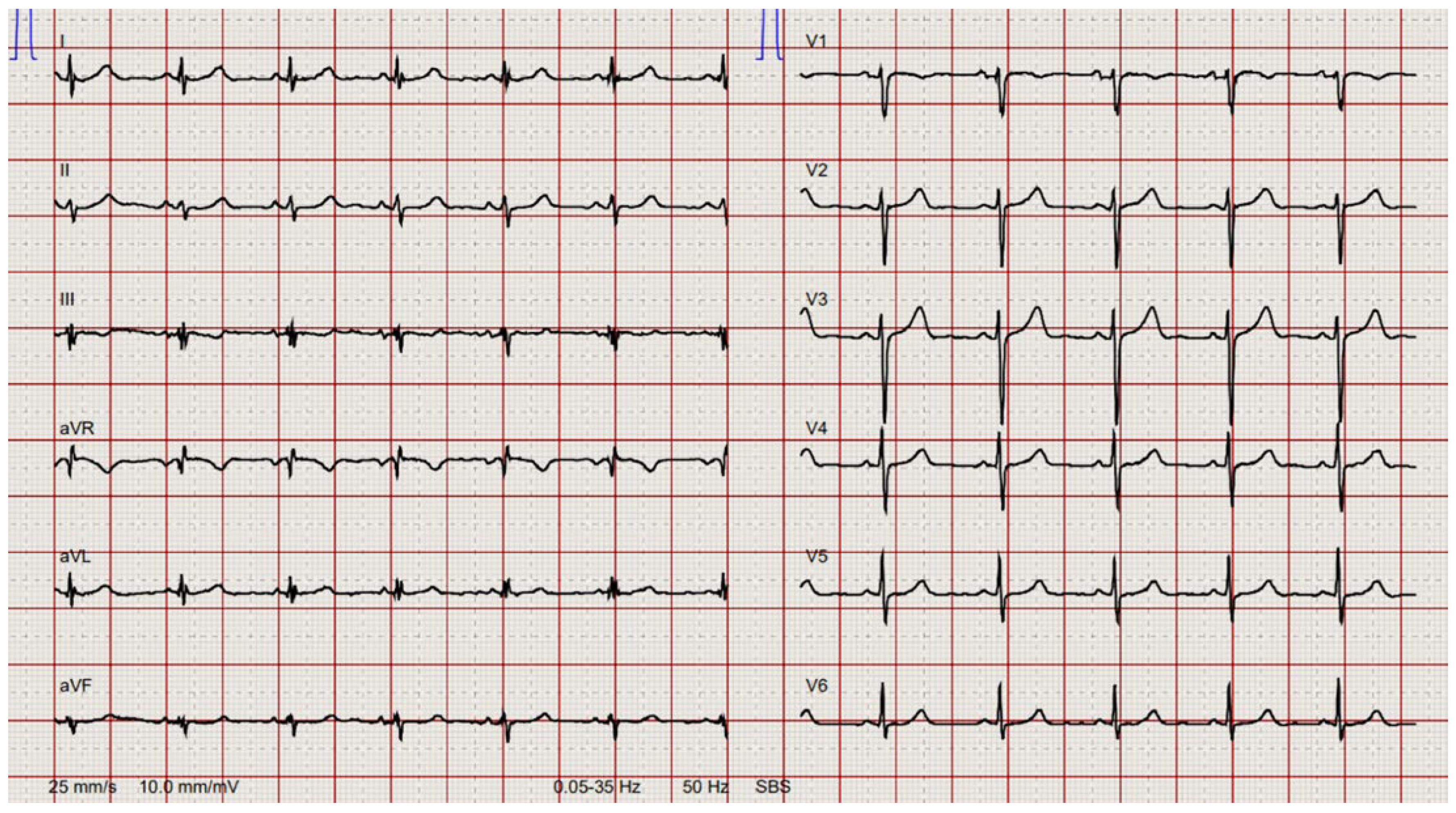

Preoperative electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with left anterior fascicular hemiblock (

Figure 1).

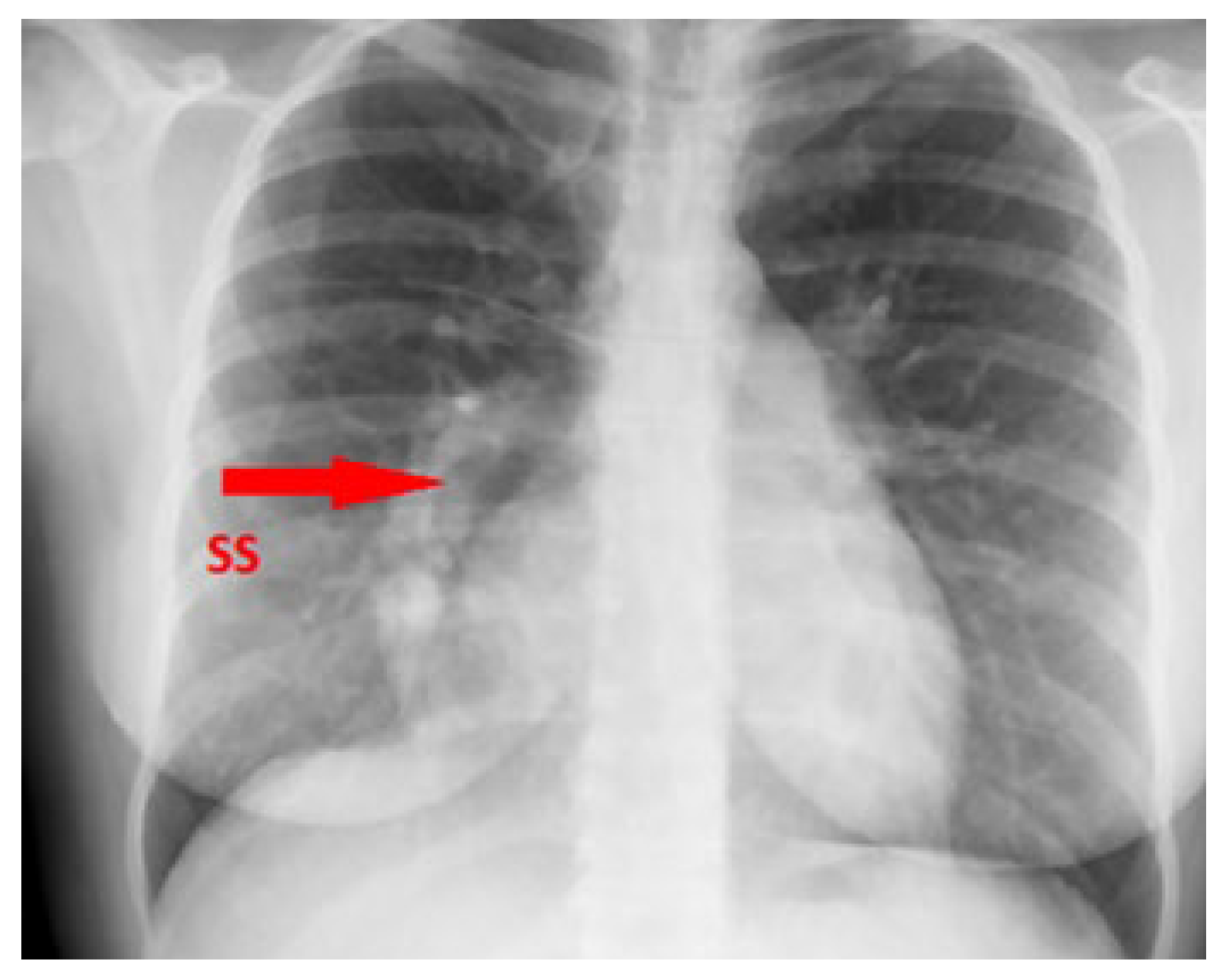

Chest X-ray demonstrated the typical right-sided curvilinear opacity with paracardial extension known as “scimitar sign” (

Figure 2).

Echocardiography revealed right heart dilatation with apical hypokinesia and an inflow aneurysm of the right ventricle. Despite the dilatation there was only minimal regurgitation of the tricuspid valve. A very small patent foramen ovale was also detected. The orifice of the inferior vena cava was conspicuously prominent.

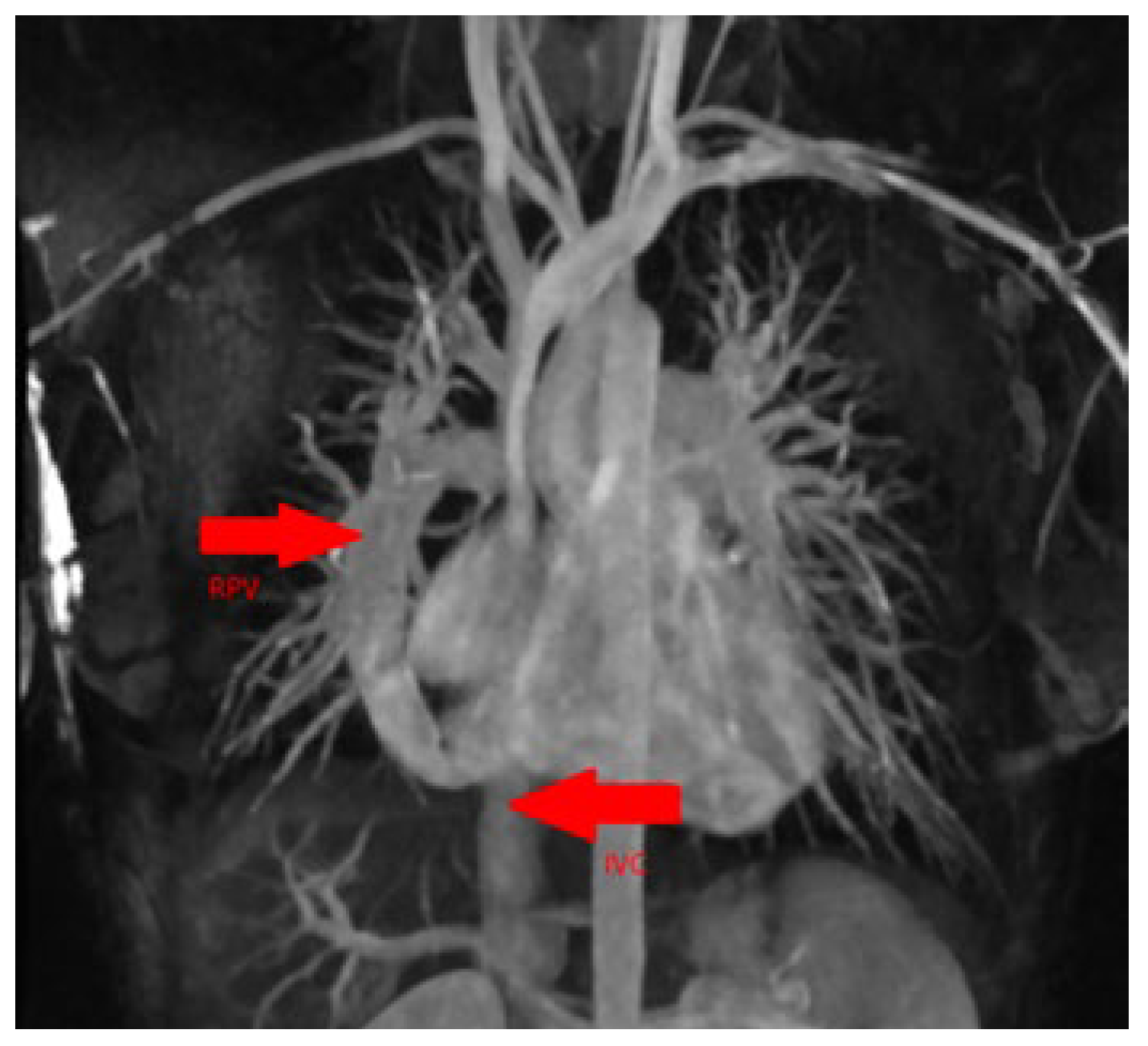

The patient was underwent chest computed tomography (CT) angiography the same day. It showed drainage of the right pulmonary vein into the inferior vena cava with concomitant hypoplasia of the right lung (

Figure 3).

No pulmonary embolism was detected nor were there any signs of structural pneumopathy. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the diagnosis of scimitar syndrome with measurement of a relevant left-to-right shunt (ratio of total pulmonary blood flow to total systemic blood flow [Qp/Qs] 2.0) (

Figure 4).

Subsequent cardiac catheterisation confirmed a significant left-to-right shunt (Qp/Qs 2.0) with a step-up in oxygen saturation from the inferior vena cava to the right atrium from 69% to 85%.

In this symptomatic patient, surgical correction was clearly indicated because of a large shunt volume with resulting right-heart dilatation and the beginning of dysfunction of the right ventricle.

At surgery the right pulmonary vein was extrapericardially transected, passed ventrally of the phrenic nerve across the pericardium and reconnected to the right atrium. The blood flow was subsequently redirected via an artificial ASD into the left atrium by creating a pericardial baffie in the right atrium. To avoid the risk of kinking of the pulmonary vein by passing behind the phrenic nerve, a direct anastomosis with the left atrium was not performed.

The postoperative course was completely uneventful, and the patient was discharged home on postoperative day 7 to follow an outpatient rehabilitation programme.

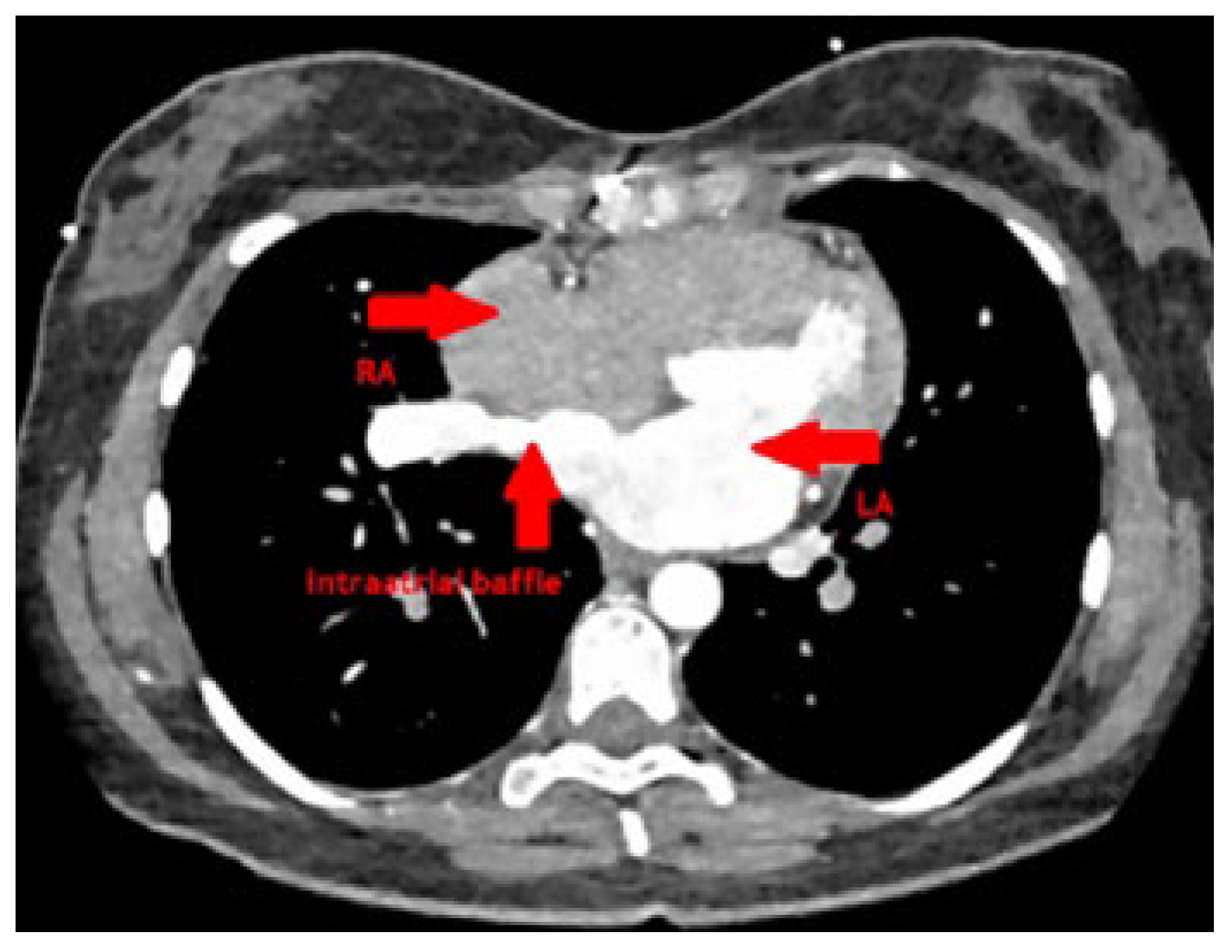

At follow-up after 3 months, she was well recovered and reported marked improvement of her exercise capacity as well as her dyspnoea. CT scan showed a good postoperative result without any stenosis of the redirected pulmonary vein and a wide baffie tunnel into the left atrium (

Figure 5). Transthoracic echocardiography 5 months after surgery showed unobstructed flow across the redirected right pulmonary vein and the baffie and normalised right ventricle dimensions and function.

Discussion

Scimitar syndrome is a special and rare form of PAPVC, consisting of an anomalous pulmonary venous drainage of the right lung to the inferior vena cava. It is often associated with other abnormalities, such as hypoplasia of the right lung and right pulmonary artery, aortopulmonary collaterals or an ASD.

When diagnosed in childhood, severe symptoms such as respiratory failure, recurrent infections or cyanosis are present. In cases with heart failure and irreversible pulmonary hypertension, the prognosis is poor, and the only surgical option may be combined heart-lung transplantation.

Our patient presented with typical symptoms of the adult form of scimitar syndrome: mild symptoms, consisting of progressive dyspnoea and moderate exercise intolerance. A multimodal diagnostic work-up is always necessary in these cases.

The first-line choice is echocardiography as it is readily available and it can rule out other causes of right heart overload such as an ASD. However, detection of all pulmonary veins can be difficult and requires a certain amount of experience. CT angiography is an important tool to assess the exact vascular pathology, drainage of the pulmonary veins and to exclude other pulmonary diseases.

Supplementary MRI provides useful additional information on intracardial volumes, valvular function and haemodynamics, and avoids irradiation. Nevertheless, it demands patient’s compliance and is quite cost intensive.

Cardiac catheterisation rules out any concomitant coronary disease and gives additional proof of a left-to-right shunt including direct measurements of oxygen saturation.

The adult scimitar syndrome is always an indication for surgical correction, whereas established severe right heart failure, fixed severe pulmonary hypertension or Eisenmenger syndrome may make surgery prohibitive.

The first corrective surgical procedure was performed in 1956 by Kirklin and Colleagues using cardiopulmonary bypass [

7].

There are several surgical approaches to the correction of scimitar syndrome:

With suitable anatomy, direct anastomosis of the anomalously draining pulmonary vein with the posterior wall of the left atrium and closure of a possible ASD can be performed. A small left atrium can be challenging in this setting and the vein should sufficiently be mobilised to avoid kinking or stretching. This procedure can be performed via right thoracotomy without the use of a cardiopulmonary bypass [

8].

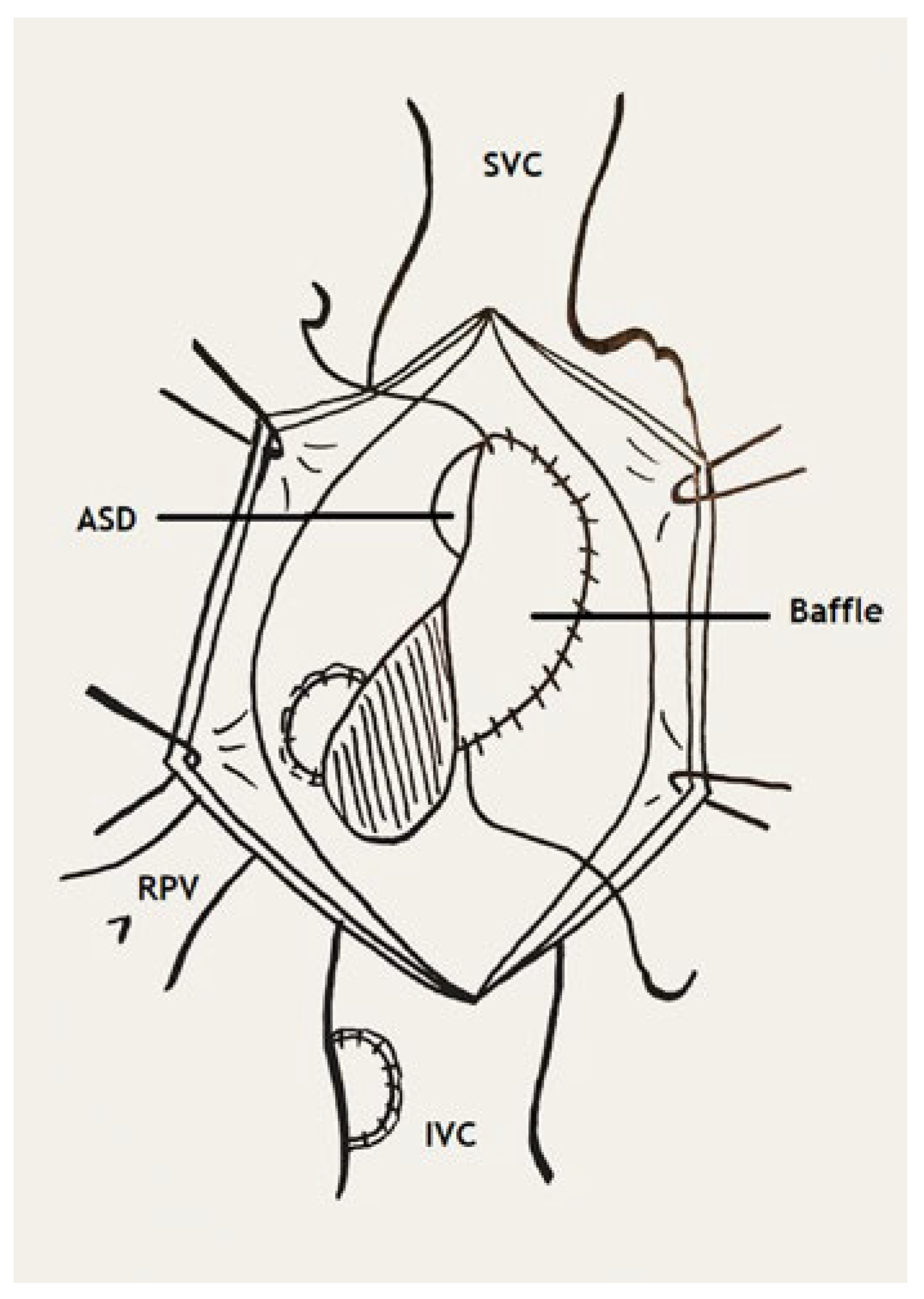

Another approach is the redirection of the anomalous pulmonary vein into the left atrium across a pericardial baffie and the existing or artificial ASD. This method carries the risk of obstruction of the created tunnel as it may be of great length, or of the inferior vena cava by the baffie. Lastly, the scimitar vein can be connected to the right atrium and redirected into the left atrium via a pericardial baffie through an artificial or existing ASD, as in our case. The use of an interposition graft between the scimitar vein and the connected right atrium may be necessary to reduce the risk of tension or kinking [

9].

Figure 6.

Correction with pericardial baffle. ASD (arrow): atrial septal defect; IVC: inferior vena cava; SVC: superior vena cava; RPV: right pulmonary vein (Adapted from Ziemer G, 2017, p. 316 [

10]).

Figure 6.

Correction with pericardial baffle. ASD (arrow): atrial septal defect; IVC: inferior vena cava; SVC: superior vena cava; RPV: right pulmonary vein (Adapted from Ziemer G, 2017, p. 316 [

10]).

Patients with scimitar syndrome present a special and challenging subgroup of PAPVC regarding the surgical long-term outcomes. A higher rate of postoperative pulmonary venous stenosis was seen after repair with the creation of an intracardiac baffie, especially when of greater length [

11]. Risk factors include original pulmonary vein orifice stenosis, potential shrinkage of the pericardial patch or the relative stasis due to sudden change in the direction of blood. Nevertheless, further follow-up data are needed to recommend one single technique of surgical correction.

Conclusion

The scimitar syndrome in adults can easily be overlooked due to mild or non-existing symptoms. It is essential to diagnose and treat it before right heart dysfunction develops. Progressive right heart failure increases the periprocedural risk or even represents a contraindication to surgery. Though, when detected early, surgical correction can be performed safely with good clinical outcome.